Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Sprawl Retrofit: Sustainable Urban Form in Unsustainable Places

Transféré par

blaaaaahhhhhTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sprawl Retrofit: Sustainable Urban Form in Unsustainable Places

Transféré par

blaaaaahhhhhDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 2011, volume 38, pages 952 ^ 978

doi:10.1068/b37048

Sprawl retrofit: sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

Emily Talen

School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, School of Sustainability, Arizona State University, PO Box 875302, Tempe, AZ 85287-5302, USA; e-mail: etalen@asu.edu Received 15 April 2010; in revised form 7 January 2011; published online 2 November 2011

Abstract. This paper makes a contribution to the suburban retrofit/sprawl repair literature by suggesting a method that planners can use to evaluate the potential of some places to be catalysts for an improved more sustainable urban form. The strategy is aimed at evaluating and then promoting sustainable urban form in unsustainable places. The method puts sprawl retrofit projects into a larger planning framework, suggesting ways to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of places in relative terms, taking into account how different kinds of nodes from light rail stops to parking lots varying with respect to sustainable urban form characteristics. Overlaying data on accessibility, density, diversity, and connectivity reveals areas with varying levels of sustainable urban form. Intervention in potential retrofit locations consists of neighborhood and site-scale design, including suggestions for code reform, intensification of land use around nodes, public investment in civic space, traffic calming, and incentives for private development.

The need to support a more sustainable urban formcompact, mixed-use, walkable now lies front and center in current planning agendas. Three convergent and interrelated forces have recently elevated this interest: (1) the need to reduce energy consumption and `live local' (climate change); (2) the need to build incrementally and in small-scale ways (the global recession); and (3) the need to provide smaller and more centrally located housing types (demographic change). Most of the interest in transforming existing unsustainable form into something more sustainable is focused squarely on the suburbs. Time magazine rated ``recycling suburbia'' as the number 2 ``Idea Changing the World'' (Walsh, 2009), and Dwell magazine recently sponsored a suburban design competition called ``Reburbia'', devoted to ``re-envisioning'' suburban growth (http://www.re-burbia.com). A recent ``Sustainable Suburbs'' symposium sponsored by the Urban Land Institute in conjunction with World Habitat Day explored ways to ``leverage'' investment in order to promote more sustainable urban form in the suburbs (ULI, 2009). A supporting literature has also emerged, with titles like Retrofitting Suburbia (Dunham-Jones and Williamson, 2008), Sprawl Repair (Tahchieva, 2009), Big Box Reuse (Christensen, 2008), Suburban Transformations (Lukez, 2007), Malls Into Mainstreets (CNU, 2005), Superbia! (Chiras and Wann, 2003), and Greyfields Into Goldfields (Sobel and Bodzin, 2002). The Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) has long been a proponent of ``sprawl retrofit'' strategies, featuring the topic on its website and at its annual meetings (http://www.cnu.org). Much of this interest is geared to architects and developers working on a site-bysite, project-by-project basis. Thus failed malls are converted to main streets, McMansions become apartment buildings, and big-box stores are reenvisioned as agricultural land. The projects can be small, like ``punctuation marks'' designed to ``activate `dead' or neutral spaces'' (Ellin, 2006, page 124), or they can be much larger. The authors of Retrofitting Suburbia argue that the urgency of suburban transformation warrants the need for ``instant cities'', involving redesign of large areas all at once in the hope that large ``single-parcel projects'' can have an effect on surrounding areas (Dunham-Jones and Williamson, 2008, page 5).

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

953

This paper makes a contribution to the suburban retrofit/sprawl repair literature I use the term `sprawl retrofit'by suggesting an analytical approach that planners can contribute to the task. The analysis is specifically limited to the US context, which is arguably the country with the greatest need for sprawl repair. I propose a method that planners with their focus on city and neighborhood scales (as opposed to `sites' or `projects'), can introduce as an additional means of evaluating the sustainable characteristics of places, and therefore build support for generating sustainable urban form in unsustainable places. The method is intended to incorporate sprawl retrofit strategies into a larger planning framework: one that could be part of a general plan update or neighborhood planning effort. Using Phoenix, Arizona and a case study, I show how planners can first evaluate the retrofitting potential of nodes, and then approach the task of retrofitting unsustainable places in ways that position singular projects more strategically. How might planners use their skills at plan making to transform ``a thousand-square-mile oasis of ranch homes, back yards, shopping centers, and dispersed employment based on personal mobility'' (Gammage, 2003, page 146) into a more sustainable city? The method is implemented at the scale at which planners typically operateie the organization and management of lots, blocks, land uses, and streets, and the collective form and pattern of buildings. Unfortunately for urban planners, this is often the most difficult scale at which to instill a more sustainable pattern because, unlike green building or technological approaches to sustainability, it requires behavioral changeie a loss of automotive freedom, the prioritization of walking, an acceptance of more compact living, and tolerance for social diversity and land-use heterogeneity. Yet these adjustments will be difficult to avoid, given their impact on sustainabilitylow-rise, spread-out buildings have significantly higher carbon footprints than apartment buildings and high-rises (Rybczynski, 2009). Compact neighborhoods bring with them the intrinsic environmental, social, and economic benefits of living smaller, closer, and driving less, including a reduction in vehicle miles traveled (VMT), lower energy costs, strengthening of social connection, and strengthened networks of economic interdependence (see Owen, 2009). While a significant literature supports the need for compact, mixed-use, pedestrianoriented cities (Ewing et al, 2008a; Frey, 1999; Jenks and Dempsey, 2005), few are prepared to dictate the specific levels of density, mix, and the like that a more sustainable urban form would require. A typical summation of what sustainable urban form actually means argues the point generally, such as Frey's (1999) call for an urban structure that ``enables a high degree of mobility and access ... a symbiotic relationship between city and country ... social mix ... self-sufficiency ... [and] highly legible and imageable settlement forms'' (page 342). We know that VMT and carbon emissions decline as density and mixed use increase (Cervero and Kockelman, 1997; Ewing et al, 2008b), but there are no specific rules about how the form of density or the level of mixed use should vary given different regions and contexts. The retrofitting analysis presented in this paper is premised on this kind of variability, arguing that planners can help prioritize retrofitting strategies based on a better, more contextualized understanding of sustainable urban form and its dimensions. In Phoenix, places that have the potential to catalyze sustainable urbanism called `nodes'can be assess on the basis of how they score on different dimensions of urban form in a relative way. This is an approach that helps planners work with what they have. It is not an attempt, as one defender of Phoenix has complained, to ``impose the shape, form, and values of Greenwich village'' on Phoenix through ``high residential densities [and] vast mass transit schemes'' (Gammage, 2003, pages 146 ^ 147), but neither does it take the view that single-use subdivisions and strip malls are a legacy to be continued. The question to be posed is: given the existing form of a place like

954

E Talen

Phoenix, how might planners realistically approach the task of advancing sustainable urban form in a way that is both realistic and responsive to local context? The approach offered here involves evaluating places for their overlapping layers of urban quality, and then proposing future public and private investment that works off the strengths and weaknesses of potential retrofitting target areas. As with all planning endeavors in the US, there will be limitations in terms of what planners can accomplish with this. Market forces and the politics of urban redevelopment will often override a more measured sprawl retrofitting strategy. Still, this paper suggests that there is nothing stopping planners from at least introducing a more sophisticated retrofitting logic into the plans they help to develop. A `one size fits all'' approach, whereby every city becomes a mosaic of walkable mixed-use neighborhoods and connecting boulevards, is often resisted not only for its lack of realism, but for its disconnection from underlying economic and cultural conditions (Marshall, 2000; Scheer, 2010). What planners have come to acknowledge is that the definition and actualization of compact, walkable, diverse cities is something that will require local sensitivity, a certain level of flexibility, and adjustment of initial expectations (Goodchild, 1994; Knaap et al, 2007; Yang, 2008). This paper presents an example of just this kind of adaptation. I draw on the standard principles of sustainable urban form but show how these principles can be evaluated strategically. What is sustainable urban form? Defining and measuring sustainable urban form sometimes termed `sustainable urban neighborhoods' or `sustainable urbanism'has advanced significantly over the past two decades (eg, Breheny, 1992; Clemente et al, 2005; Far, 2008; Frey, 1999; Jabareen, 2006; Jenks and Dempsey, 2005; Mazmanian and Kraft, 1999; Miles and Song, 2009; van der Ryn and Calthorpe, 2008; Wheeler, 2005; Williams et al, 2000). Sustainable urban form has walkable and connected streets, compact building forms, well-designed public spaces, diverse uses, mixed housing types in short, qualities that often run counter to a previous generation of city building that promoted segregated land use, superblock `projects', socially insular and physically disconnected housing, and car-dependent subdivisions and shopping malls. The concept of a `sustainable city' is broader and includes more than the physical qualities of built form (Farr, 2008; Newman and Jennings, 2008; Roseland, 2005). For example, institutional strategies like recycling programs, local governance, and civic participation are considered important for promoting sustainable cities. Sustainable industrial and energy systems, food production, and mitigation of heat-island effects are also essential. Sustainable cities support passive solar design, sustainable stormwater practices, organic architecture, the harnessing of waste heat, and the protection of biodiversity corridors all of which are impacted by urban form, but not synonymous with it. My focus is on the human-built dimensions of urban formstreets, lots, blocks which constitute what Scheer (2001) calls the ``static tissues'' of urbanism. Planners know what the sustainable urban qualities of these static tissues are likely to be, supported by research linking urban form to public transport (Cervero, 2009), physical health (GilesCorti and Donovan, 2003; Moudon et al, 2006), social equity (Murray and Davis, 2001; Talen, 1998), global warming (Ewing et al, 2008a; 2008b), and environmental quality (Beatley, 1999; Newman and Jennings, 2008), among other linkages. Planners' commitment to walkable, compact, diverse urban form is now bolstered by research that shows that support for ``traditionally designed communities'' is increasing (Handy et al, 2008), and there are predictions that demand for walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods is likely to grow in the coming decades (Leinberger, 2008; Levine et al, 2005).

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

955

But what are the particular dimensions of sustainable urban form that can be measured and evaluated? The measures used here are based on morphological concepts of form, rather than sustainability defined by environmental characteristics (eg, water conservation, habitat protection, drainage, stormwater systems, passive solar design, or district energy systems), or building and site design (eg, building layout, heating and cooling systems, or microclimate conditions). Reviewed below are the most important dimensions of relevance to urban planners: accessibility, connectivity, density, diversity, and nodality.

Accessibility

Accessibility is a long-standing component of theories of good (ie, sustainable) urban form (see in particular A Jacobs and Appleyard, 1987; J Jacobs, 1961; Lynch, 1981). A sustainable settlement pattern should increase access between residents, their places of work and the services they require (Dittmar and Ohland, 2003). In this way, accessibility is tied to the principles of smart growth (Song and Knaap, 2004) and active living environments (Heath et al, 2006; Norman et al, 2006) in which pedestrian access to daily life needs is viewed as especially important. Measures of access have been used extensively in the past few years as part of an effort to evaluate the built environment for health effects (eg, Greenwald and Boarnet, 2001; Moudon and Lee, 2003). Walkable access to services is an essential part of the sustainability equation because people living in well-serviced locations will tend to have lower carbon emissions (Ewing et al, 2008a). The higher the access to opportunities like jobs and services, the lower the transport costs. Related to this, sustainable urban form is defined by the degree to which it supports the needs of pedestrians and bicyclists over car drivers (Moudon and Lee, 2003). This has been motivated by a concern over the effects of the built environment on physical activity and human health. Streets that are pedestrian oriented are believed to have an effect not only on quality of place but on the degree to which people are willing to walk (Forsyth et al, 2008). Researchers have argued that activity levels can be increased by implementing small-scale interventions in local neighborhood environments (Sallis et al, 1998), and a whole catalog of design strategies are now used to make streets more pedestrian oriented (ITE, 2005). Connectivity, a related concept, refers to the degree to which local environments offer points of connection and contact (to people and resources) at a variety of scales and for multiple purposes. This quality promotes sustainability in that higher connectivity leads to higher levels of interaction between residents and the environment, society, and cultural and economic activityall of which is believed to improve neighborhood stability in the long term. Urban form plays a significant role in promoting or constraining connectivity. The underlying mechanisms involved have been investigated at a variety of scales, from microenvironmental factors and site layout to regional systems. Social connection at the neighborhood scale is seen as a pedestrian phenomenon (Michelson, 1977), and networks of `neighborly relations' are related to interconnected pedestrian streets and the internal neighborhood access those street networks engender (Grannis, 2009). The importance of maximizing connectivity in urban space is a common theme in urban form studies (Alexander, 1965; Hillier and Hanson, 1984), where the main focus is on maximizing opportunities for interaction and exchange and increasing the number of routes (streets, sidewalks, and other thoroughfares and pathways) through an area. Providing alternative routes and access points affects both the public space network and the corresponding patterns of movement (Salingaros, 1998). From an urban form point of view, increasing connectivity translates to gridded street networks, short

Connectivity

956

E Talen

blocks, streets that connect rather than dead-end, establishment of central places where multiple activities can coalesce, and providing well-located facilities that function as shared spaces (Carmona et al, 2003). It is generally agreed that large-scale blocks, cul-de-sacs, and dendritic (tree-like) street systems are less likely to provide good connectivity (Trancik, 1986).

Density

Density is another essential component of sustainable urban form. There is some disagreement over the exact relationship between density and sustainability, particularly as it relates to social justice goals (Burton, 2002; Jenks et al, 1996). But there is general agreement that cities that are more dense and compact and less sprawling and land consumptive are likely to be more sustainable, especially in environmental and economic terms. Among many other negative effects, identified in studies like Costs and Sprawl (Burchell et al, 1998; 2005), low-density development has been linked to higher infrastructure costs (Speir and Stephenson, 2002), increased automobile dependence (Cervero and Wu, 1998), and air pollution (Stone, 2008). Density has been seen as an essential factor in maintaining walkable, pedestrian-based access to needed services and neighborhood-based facilities, as well as a vibrant and diverse quality of life (Jacobs, 1961; Kunstler, 1994; Newman and Kenworthy, 2006). Diversity is an important dimension of sustainable urban form. In particular, land-use diversity is related to foster a number of sustainability benefitseconomic vitality, social exchange, accessibility, and walkable provision of the diverse services and facilities a neighborhood requires. Socially diverse neighborhoods continue to be seen as essential for broader community well-being and social equity goals (eg, Popkin et al, 2009; Turner and Berube, 2009), but the connection to sustainability is also made mixing incomes, races, and ethnicities is believed to form the basis of `authentic', sustainable communities (CNU, 2000; see also Talen, 2008). Mixing housing-unit types is an important strategy. Also essential are land use that complement each other to promote the active use of neighborhood space at different times of the day, creating ``complex pools of use'' (Jacobs, 1961), a component of natural surveillance and social sustainability. Supporting this are findings that a mix of neighborhood public facilities plays a role in reducing crime (Colquhoun, 2004; Peterson et al, 2000). Studies of socially mixed neighborhoods consistently identifying urban form as a key factor in sustaining diversity (Nyden et al, 1997). Finally, sustainable urban form is associated with what could be termed polycentric or multinucleated urbanismthe idea that urban development should be organized around nodes of varying sizes (see Frey, 1999). Whereas sprawl tends to be spread across the landscape uniformly, sustainable urban form has a discernible hierarchy to itfrom regional growth nodes to neighborhood centers or even block-level public spaces. At the largest scale, centers may be conceived as regionally interconnected `urban cores', with higher intensity growth converging at transportation corridors, a strategy supported by the Phoenix General Plan (Hall and Karnig, 1984). At the neighborhood level, nodes support sustainable urban form by providing public space around which buildings are organized. It is not a place where all shopping and social interaction necessarily occurs, nor does it need to be literally at the center of a population. Neighborhood cores have been conceived as being either along major thoroughfares or away from them (constituting a neighborhood edge), although other conceptions based on pedestrian activity have also been proposed (Mehaffy et al, 2009).

Nodality Diversity

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

957

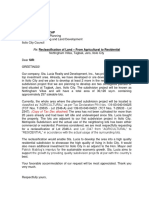

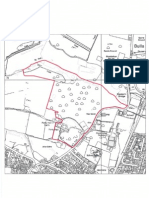

In all cases, neighborhood-scale centralized spaces or nodes of activity can provide a physical articulation of `community'a place-based connection that people living in the same area necessarily share. By providing a common destination for surrounding residents, such spaces support other aspects of sustainable urbanism, such as increases in surrounding density, mixed housing type anchored by a centralized space, or the viability of neighborhood-based retail. At the smallest scale, the idea of nodality is not unlike ``urban acupuncture'' (Ellin, 2006, page 124), which seeks to leverage small-scale interventionsstratefically located nodesfor wider effect. (Un)sustainable urban form in Phoenix These dimensions that define sustainable urban form can be easily contrasted with the sprawling metropolis of Phoenix, now the fifth largest city in the US. It is a quintessential sunbelt city, built mostly of post-World-War-II suburbs, and organized almost entirely to accommodate private modes of consumption (see Hayden, 2003). Between 1950 and 1970 the urbanized area of the region (which includes thirty-two incorporated municipalities surrounding Phoenix) grew 630%, while its population grew 300% (US Census). Unfetted growth in Phoenix over the past sixty years has resulted in a predictably harsh, automobile-dependent environment (Gober, 2006), as evidenced by the map of street-facing surface parking lots shown in figure 1. Until the recent recession slowed expansion in the region, developers had been making vast fortunes building large-scale, leapfrog residential development of homogenous `product', with little regard for the cumulative effect on Phoenix's social and environmental quality (Schipper, 2008). Phoenix is a relatively young city (incorporated in 1881), and had a population of just 30 000 in 1920. Initial interest in planning Phoenix began in the 1920s, when a City-Beautiful-like plan (including a civic center, railway stations, boulevards, parkways, and parks) was completed by Edward Bennett, Daniel Burnham's partner on the Chicago Plan of 1909. Only a small portion of this plan was realized. Of more interest at the time was the adoption of comprehensive zoning. A zoning plan was adopted soon after the Bennett plan, following a clamor for ``utility over beauty'', and a desire for a more business-oriented planning approach (Larsen and Alameddin, 2007, page 111). Phoenix is now burdened with the usual array of poorly conceived regulations (zoning), and public fund expenditures are directed toward road-widening projects that accommodate far-flung growth. Aside from zoning, long-range comprehensive planning in Phoenix has been weak (Collins, 2005; Schipper, 2008). While Phoenix's planning department is charged with guiding physical development, city planners have so far been unable to reverse the tide of unsustainable growth. The state recently adopted a Growing Smarter Act whereby plans and zoning are required to be in conformance, but development remains predominantly a project-by-project affair, driven by the narrow ``let's-make-a-deal trivia of development'' rather than broader concerns about land-use policy (Gammage, 2003, page 141). And, although Phoenix is divided into fourteen ``urban villages'' (figure 2), they are little more than ``lines on a map'' (Gober, 2006, page 203) whose essential purpose is to organize community input (mostly opposition) on rezoning requests. Planners in Phoenix are thus confronted with strong and well-researched ideas about sustainable urban form, but few realistic options for implementing those ideals. This is not to say there are no successes. Planners in Phoenix have been successful in supporting light rail, and the new Metro Light Rail (opened in 2008) is likely to promote sustainable urban form in the long term. Overlay zoning for transit-oriented development was put in place to help stimulate compact urban development (ie, sustainable urban form) around the new transit stations.

958

E Talen

6 miles

Figure 1. Street-facing surface parking lots in the main developed areas of Phoenix. The small rectangle is the downtown.

Planners have had more limited success in their attempts to foster better regional cooperation among local governments, in support of sustainability. There is hope that land-use and infrastructure planning can be combined in a way that considers larger areas of the region as single planning entities (Morrison Institute, 2008), but there is little evidence that this integration is occurring. Like many large cities, Phoenix has a metropolitan coordinating entity (Maricopa Association of Government), whose primary purpose is the planning of new highway development (Davis, 1996), despite claims to be concerned with broader regional planning principles. Lack of political backing for coordinated regional infrastructure planning for water, transportation, and land use remains a significant challenge (Gober, 2006).

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

959

2.5

5 miles

Figure 2. [In color online.] Fifteen urban villages and 856 neighborhood associations in Phoenix.

Given existing political realities and a relatively weak planning culture, how might planners reasonably support the development of a more sustainable urban form in Phoenix? Since the form and pattern of Phoenix stand in stark contrast to principles of sustainable urban form, it is not realistic to propose that all of Phoenix be transformed into walkable, pedestrian-oriented neighborhoods but what steps could planners take in that direction?

960

E Talen

Evaluating sustainable urban form in Phoenix Given the contrast between ideal (sustainable urban form) and reality (low-density subdivisions and a weak planning culture), transforming Phoenix into a city of sustainable urban neighborhoods defined as walkable, compact, and mixed useor, accessible, connected, dense, diverse, and nodal will necessarily require flexibility. How can planners proactively create sustainable urban form in this context? One question to explore is whether it makes more sense to revitalize an area that has at least some characteristics of sustainable urban form, or, whether it would be better to target investment in places that are the worst kind of sprawl, for example, a `dead' suburban mall with no surrounding population or walkable urban form. In short, where should sprawl retrofit be targetted? I approach this question by evaluating the potential sustainability of a range of possible locationsplaces that could be thought of as potential nodes of future sustainable urban form. Conceptually, potential nodes could range from places that are transit served and thus already sustainable, to places that are the most in need of retrofitting strategies, such as vacant parking lots. How might one location be considered better than another as a place to recommend policies that promote the transition to sustainable urbanism? How might a range of possible locations be compared? If cities are going to prioritize locations for suburban retrofit and sprawl repairtransitioning from an unsustainable urban fabric to one that has at least pockets of sustainabilityhow might they approach such a task? To answer this question, I evaluated four types of potential nodes in Phoenix and compared the degree to which they satisfied the goals of sustainable urban form. This comparison was intended to answer the following question: if the goal is to find and promote some locations as sustainable places in terms of urban form accessible, connected, dense, diverse what locations are furthest along in terms of satisfying the basic requirements? In relation to this question, I wanted to know whether one location was stronger on some aspects of sustainable urban form than another. I selected the following four types of places that could provide the `nodality' dimension of sustainable urbanism in Phoenix. The first two reflect previous strategizing by the City of Phoenix to stimulate sustainable urban form in core locations. The second two can be viewed as possible alternative locations for retrofitting activity. 1. Seventeen Phoenix ``cores'' identified in the Phoenix General Plan (updated in 2008). These cores are intended to serve as a ``focal point'' to each Phoenix village, providing a mix of uses, a ``physical identity'' and ``a gathering place with pedestrian activity'' (City of Phoenix, http://phoenix.gov/PLANNING/gpland1.pdf). Both primary and secondary cores identified in the plan were used. 2. Twenty-four Phoenix Light Rail Transit station (LRTs) areas. These locations would seem to be obvious targets for the promotion of sustainable urban form. 3. Nineteen parking lot nodesareas in which surface parking lots make up a significant portion of developed land area. These were selected on the basis of the ratio of parking lot area to total area by census block group. For these nineteen block groups, parking lots make up more than a third of the land area of the block group. 4. Twenty-one shopping center nodesshopping centers (malls and strip malls) that are within a quarter mile of both a publicly owned park and elementary school. Despite being auto-dependent malls, these locations might form the nucleus of a more sustainable urban form, given their proximity to essential public facilities. I use the measures of sustainable urban form identified aboveaccessibility, connectivity, diversity, density to identify varying levels of sustainable urban form. The measurement methods are shown in table 1. The measures draw from some of the more standard measures of urban sustainability that have become prolific in the literature

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

961

Table 1. Calculation of four measures of sustainable urban form. Measure Density Diversity Connectivity Accessibility

a The

How measured population per square mile housing-type diversity a street centerlines per area of tract; and intersections per area of tract count of residential parcels within a 500 ft of retail, divided by area of tract

Spatial unit block group tract tract tract

Simpson diversity index was used to calculate diversity. Categories were: 1 unit detached, 1 unit attached, 2 units, 3 or 4 units, 5 9 units, 10 19 units, 20 49 units, 50 units.

[see Condon et al (2009) for a recent review of some of these measures]. Specifically, density is a straightforward measure of population per square mile; access is measured based on distance between residential parcels and retail; and connectivity uses two standard measuresstreet centerlines and intersections per area. For diversity I use tracts that scored high on the Simpson diversity index for housing-unit type.(1) The rationale is that areas with a greater mix if housing unitsfrom single-family detached to apartment buildings would have an urban form more supportive of social diversity, a key feature of sustainability. Figure 3 shows the locations of the four types of nodes, together with the areas that had the highest levels of density, diversity, connectivity, and accessibility. Figure 4 is a closer-in view of the same map, showing the central and northern parts of the city in which most people in Phoenix live. An immediate impression is that the most sustainable areas do not seem to bear much relation to the potential nodes. This would not be surprising in the case of block groups with high surface parking. It is more surprising in the case of Phoenix's core areas and LRTs. Table 2 and figure 5 present the results numerically. Table 2 presents comparative statistics using mean scores, while figure 5 shows medians and boxplates of the distribution of all scores. Several observations about these data can be made. First, the results indicate that Phoenix cores do not score particularly well in terms of sustainable urban form. They do not rank highest on any measure, and clearly rank lowest in terms of density and connectivity. Second, LRTs do score slightly higher than the other locations on the diversity measure (in terms of overall distribution), but not in terms of density, connectivity, or accessibility. Third, shopping centers appear to be better connected and have higher accessibility than all other node types, although they do less well on diversity measures. Finally, parking lots appear to do well in terms of density and diversity, but do less well on other measures. It is especially significant that parking lots do not score worse on sustainable urban form measures than Phoenix's designated cores. Ultimately, it may be that the level of investment needed to get Phoenix's core areas to a level of sustainable urban form is significantly higher than that needed for shopping centers close to parks and schools. Shopping centers scored higher than Phoenix cores on all measures of sustainable urban form, indicating that there might be fewer costs associated with achieving sustainable urbanism in those locations.

housing-type categories were used: referring to figure 5, a score of `6' indicates very high diversity, while a score of `1' indicates very low diversity (no tracts had all eight categories). For more information on the methods used for the diversity calculation, see Talen (2008). The Simpson diversity index is also used in the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design ^ Neighborhood Development (LEED ^ ND) rating system (US Green Building Council, 2009).

(1) Eight

962

E Talen

On the other hand, shopping centers near parks and schools tended to score low in the diversity measure, which is especially significant given the policy goal that access to public facilities should be maximized for a broad range of income levels.

6 miles

General plan core Light Rail Transit stations, shopping centers, parking-lot density Dense, diverse, connected, accessible

Figure 3. Nodes of potential, together with areas that scored highest on four measures of sustainable urban form.

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

963

2 miles General plan core Light Rail Transit stations, shopping centers, parking-lot density Dense, diverse, connected, accessible

Figure 4. Nodes of potential, together with areas that scored highest on four measures of sustainable urban form central Phoenix.

The results point to several complexities that seem counterintuitive. How could it be that shopping centers are more connected than cores and LRTs, or that block groups defined by high levels of parking are also areas that score better in terms of density? In fact these contradictions are explained by looking more closely at the urban forms that score highly on sustainability criteria. Figures 6, 7, and 8 show some examples. Figure 6 shows a shopping center node that scored high on accessibility ie, the tract contains a relatively high number of parcels that are close to retail. It is doubtful, however, that this area would qualify as sustainable urbanism by most definitions.

964

E Talen

30 20

6 4 2 0

Density

10

(a)

0.04 Connectivity 0.03 0.02 0.01 0.00 Connectivity

(b)

0.00015 0.00010 0.00005 0

Diversity

(c)

150 Accessibility 100

(d)

Cores Light Rail Parking Shopping Transit lots centers stations

50

0 Cores Light Rail Parking Shopping Transit lots centers stations

(e)

Figure 5. [In color online.] Box plots comparing measures of sustainable urban form for four types of suburban retrofits (`nodes'): (a) density (population per acre), (b) diversity (Simpson diversity index, by census tract, for housing type), (c) connectivity (density of street centerlines), (d) connectivity (density of intersections), (e) accessibility (count of residential parcels close to retail).

What this does show, however, is that higher sustainability on one variable, for one type of node, can provide something to work with. Figure 6 is an area with many of the right ingredientsretail, park, school, residentialall in relatively close proximity. The higher accessibility of this area might be used as leverage to promote a fuller degree of sustainable urban form, targeting increases in other dimensions, such as connectivity. Drawing these kinds of visual connections between data and form provides insight about the kind of retrofitting strategy that might be most appropriate. Two areas identified in figure 4 (labeled `1' and `2') can be similarly investigated. Aerial views of the two locations are shown in figure 7. Area 1 contains all four types of potential nodes an LRT, an identified core from the Phoenix General Plan, an area with a high percentage of surface parking, and a shopping center near a park and a school. What is interesting from an analytical point of view is that this area did not score high on any sustainable urban form measures. But since this area contains multiple interpretations of nodality, this might be a good area for planning

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

965

Table 2. Four suburban retrofit strategies (as `nodes') and four measures of sustainable urban form. Measure Strategy General Plan cores Light Rail Transit stations 5375 3.179 0.01 49 block groups with high surface parking 7485 3.341 0.0058 44 shopping centers within mile of school and park 6716 2.317 0.0106 63

Density (mean block group density) Diversity (mean tract diversity) Connectivity (mean score for street centerlines per area) Accessibility (mean count of residential parcels close to retail) Number of events Number of tracts

3075 2.934 0.0072 41

17 15

24 12

19 17

21 12

Figure 6. [In color online.] This shopping center node scored high on accessibility.

966

E Talen

(a)

(b) Figure 7. [In color online.] Details of (a) area 1 and (b) area 2 shown in figure 4. Area 1 is cluster of nodes, but does not score high on any measures of sustainable urban form. Area 2 is a node consisting of high parking-lot density, and scores high on three measures of sustainable urban form.

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

967

and design intervention. Area 2 is interesting for different reasons, and might require a different approach that draws on its particular strengths. The area is a node consisting of high parking-lot density which also scored high on three dimensions of sustainable urban form: density, diversity, and accessibility. The aerial photograph verifies these characteristics perfectlya place of high density and mix of uses, but with an internal connectivity that could be stronger. Figure 8 shows three areas that scored very high on density a shopping center node, an LRT node, and a parking-lot node. The images show how density varies by the type of node involved. High density for a shopping center near a park and school is configured very differently from high density near an LRT or a parking lot. The images show that it is important to recognize that, for each type of node, the kind of density that can be expected varies. Second, parking-lot areas may in fact have very high density (area C in figure 8), but that does not mean they are exemplars of sustainable urban form. In fact, all three examples of high density scored low on connectivity, and only area B scored high on unit-type diversity. Other retrofitting approaches can be similarly informed by the degree to which different types of nodes measure up to different dimensions of sustainable urban form. For example, it is useful to know that LRTs did well on the diversity measure. If the goal is to increase sustainable urban form using transit stops as nodes for retrofitting opportunities, it might be particularly important for planners to keep their strategies focused not only on increasing accessibility, connectivity, and density (which the LRTs did not score as well on), but on maintaining the relatively high levels of diversity currently enjoyed in the LRT areas. If the main objective is to look for retrofitting opportunities that do not require adding density, parking-lot retrofitting in some locations might be something to emphasize, since parking-lot nodes already had higher density than many designated cores. The variables of accessibility, density, diversity, and connectivity, and how they vary from one location or node to another, can help planners get a sense of the kinds of urban forms being considered, how their potentials vary, and what their relative strengths and weaknesses are in terms of sustainable urban form. Strategies could be modified in order to retain and strengthen whatever sustainable urban form qualities each type of node possesses. One objective might be to find locations that are already exhibiting key aspects of density and diversity, and to find ways to support development that strengthens the other dimensions of sustainable urban form (connectivity and accessibility). Planners will have to decide whether it makes more sense to promote nodes that are highly deficientie areas dominated by parking lotsor, if they should look for places that are already sustainable along at least a few dimensions. For the later category, it could be argued that places with the most potential for achieving sustainable urban form are those that already have the highest level of sustainable qualities along all dimensions. These areas might respond better to strategic intervention because they already possess the basic outlines of sustainable urban form, and therefore strengthening these qualities will not seem jarring or unprecedented. Such places might make the most sense as targets of retrofitting opportunity because they already possess aspects of sustainable urban form that can be leveraged. Knowing what places score higher than others in terms of sustainable urban form is only the first task. The next requirement is to propose mechanisms for implementing sustainable urban form in a way that recognizes how different kinds of areas measure up using a range of sustainability criteria.

968

E Talen

Population density of block group 13 308 per square mile Connectivity: low Scale: 1:5000

Population density of block group 20 122 per square mile Connectivity: low Diversity: high Scale: 1:5000

Population density of block group 36 667 per square mile Connectivity: low Scale: 1:3200

C Figure 8. [In color online.] Areas scoring high on density. Area A is a shopping center node; area B is a Light Rail Transit (LRT) node; area C is a parking-lot node.

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

969

An example retrofit Retrofitting involves three strategies: rule changes (code reform), targetted public investment to strengthen public spaces, and incentives (tax breaks or small grants) to stimulate private development. These strategies are in line with recent approaches to the planning and project management side of sustainable urban development (PiedmontPalladino and Mennel, 2009; Porter, 2009), although the focus on existing as opposed to entirely new neighborhoods makes the strategies necessarily modest. As compared with sustainable development practices geared to regional planning, for example,

General Plan core Elementary school Park 0 2 4 miles

Figure 9. [In color online.] The Phoenix General Plan does not offer explicit support for strategic intervention in area 1.

970

E Talen

sprawl retrofit requires making relatively small requests of governments or property owners. And yet, because the interventions are tied to a larger assessment of sustainable urban form and its potential in a larger, citywide planning context, the small, strategically placed interventions could have a more widespread impact. For example, area 1 (figure 4 and 7) might be a good location to pursue the goal of strengthening sustainable urban form in Phoenix. The area had definite node characteristics, including an LRT, a designated core, a mall, parking areas, a school, and a park. What it lacks is sustainable urban form along the other four dimensions: scoring

General Plan core Park Elementary school 0 2 4 miles

Figure 10. [In color online.] Zoning does not offer explicit support for strategic intervention in area 1.

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

971

average or low on every measure. Planning support for the area could consist of, for example, station-area build-out scenarios, and visualization, specific plans, investment in public space, business improvement districts, or some other geographically based investment strategy, and codes that ensure a more coherent public frontage for the blocks surrounding the station, parks, and other public areas. Planners could work to ensure that there is planning, design, and regulatory support for this kind of targetted intervention. Figures 9 and 10 show how the rules and plans currently in place for area 1 do not suggest any particular strategic approach for focused investment (despite the fact that this area is a designated core in the Phoenix General Plan). Because no assessment has been made regarding the sustainable qualities that already exist, there is no correspondence between those qualities and the rules guiding future development. Without such an assessment, neither General Plan designations, nor zoning are likely to have any particular relevance to the goal of promoting sustainable urban form in targetted locations. Intervention could consist of public investment and private regulation aimed at increasing the area's connectivity, density, diversity, and accessibility all dimensions area 1 is currently lacking. This intervention could occur at two scales: the neighborhood (blocks around the node, for example, within a quarter-mile radius around the site), and the site itself (including lots immediately adjacent). At the neighborhood scale, rezoning or code reform can be used to promote sustainable urban form in target areas. Figure 11 shows an example rezoning where just four land-use intensities are proposed around the node (area 1), instead of the current tangle of zoning categories shown in figure 10. More intensive zones toward the center encourage density,

Figure 11. [In color online.] One strategy for suburban retrofit involves code reform. In this example, area 1 is rezoned to include just four levels of intensity, greatly simplifying the existing zoning shown in figure 10, and giving it a spatial logic whereby more intensive development is encouraged toward the center.

972

E Talen

land-use mix, and other reforms of intensification, which could help establish the area as a viable node. Increasing density, mixed use, and the number of people within walking distance of the site helps increase accessibility, a key component of sustainable urban form. Away from the blocks immediately adjacent to the site, a new residential zoning category could promote diversity and density at a level that respects the neighborhood, allowing a gradual transition toward greater complexity and intensity of use. Suburban lots in this transitional area could be allowed to densify in ways that would not disrupt the neighborhood, for example by allowing additions to existing single-family lots as shown in figure 12. A variety of design and investment strategies could elevate the role of a node as an additional nucleus of sustainable growth. Figure 13 shows a design proposal for area 1. First, a public plaza is inserted at a strategic location between the park, LRT, and mall. The space is framed by new liner buildings that frame the sidewalk, buffer pedestrians from the parking lot, and create an `outdoor room'. Investment in this public space could stimulate private investment in support of this function. The civic

Figure 12. [In color online.] One proposal for increasing density in a suburban tract home area (source: Tahchieva, 2010).

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

973

Figure 13. [In color online.] Conceptual design for suburban retrofit. The image shows where public investments could be strategically located, between the school, park, and existing Light Rail Transit station (LRT). The design shows a plaza, liner buildings, and modest improvements linking the LRT station to existing and new public spaces.

importance of the space could be emphasized by adding a `build-to' line in the surrounding blocks, perhaps as part of a revised zoning code. Form-based codes could be used to reinforce these spatial definitions and create a more pedestrian-oriented urban realm. In between the public space and the LRT, a reconfigured street could promote walkability, including traffic-calming measures like road narrowing, pedestrian crossing points, the insertion of islands and medians, and tree planting. Sustainable urban form would be further promoted by increasing connectivity within and around the site. Road and path linkages could be added by cutting through underutilized spaceparking lots, vacant land, and unoccupied municipal-owned lots, aimed at increasing connectivity for pedestrians and providing routes with direct access to the public spaces. In addition to these kinds of design interventions, support for sustainable urban form requires creative policy. For the site design envisioned here, planners could push for tax incentives that support retrofit-supporting development at strategic locations. While unusual, it is not unprecedented. Promotion of retail in targetted areas has recently been tried in New York City, where tax incentives and zoning changes have been proposed in an effort to support grocery stores in underserved neighborhoods. In the private sector, incentives like free rent in the commercial sections of new planned communities have been used successfully by developers who view local retail

974

E Talen

as an essential part of sustainable urbanism. These kinds of private sector incentives are the basis of an incremental approach to sprawl repair (Steil et al, 2008). Planners could also provide `permitting by right' for property owners who build around a proposed node in a targetted location. Or they may propose a number of financial mechanisms to incentivize retrofitting at these locations. It would also be important to coordinate the investment priorities of public agencies in a way that is more place-based and directs funds toward strategic retrofit. Currently, each city department in Phoenix has its own capital-improvement program: streets, parks, and neighborhood services operate independently, with no consolidation program. It planning's goal is to promote sustainable urban form, planners may be able to use retrofitting analysis to help channel public investment toward specific locations. All of these interventions design for strategic nodes, code reform, traffic calming, tax incentives, and other public investments are part of an overall strategy of increasing the sustainability of a place, investing in the potential of one strategically located area at a time, with clear knowledge of each area's strength and limitations in sustainability terms. Conclusion Planners in contemporary American cities are confronted with two competing realities: a professional emphasis on sustainable urban formwalkable, compact, diverseand a public attitude that is often supportive ofor at least indifferent towardprivate property rights, limited government intervention, homogenous land-use patterns, and automobile-based development. This contrast is particularly pronounced in parts of the Southwest, where planning intervention does not have a strong tradition. The result is that planners are often challenged to pursue the goal of sustainable urban form in places that are largely unsustainable. Phoenix is a prime example, a city famous for its sprawling development pattern, car dependency, and inefficient use of resources. But it is important to recognize that cities like Phoenix are the result of particular ideas and choices, not the workings of some invisible hand. Such ideas and choices can be changed even in the face of markets and politics and planners are in a position to influence the direction of that change via their stock in trade: urban plans. While it may be impossible to transform Phoenix into a more sustainable urban place in the near term, it may not be unreasonable to channel support toward strategically located pockets of sustainable urbanism. If planners can garner support, they can help seemingly unsustainable places grow in more sustainable ways, one neighborhood at a time. In keeping with that modest objective, the method I demonstrate looks at the relationship between different kinds of retrofitting nodes and how they measure up in terms of sustainable urban form. With this knowledge, planners can propose strategically located interventions that focus on promoting sustainability in informed ways, addressing explicit deficiencies. If the goal is to coerce future development into a more sustainable urban form, it would be important to understand how a particular area measures up on different sustainable urban form criteria. Different kinds of nodes will have different strengths and weaknesses, and therefore different requirements for retrofitting. For example, nodes could be defined by a cluster of public and retail space, or perhaps a neighborhood corridor or section of street could be identified as a potential node type. Planners can work with constituents to develop a range of alternative retrofitting nodes to evaluate. Beyond this, the quantification of sustainable urban form accomplishes two important tasks. First, it provides a degree of objectivity in determining investment priorities.

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

975

The measurement of urban form has lately become a familiar task, commonly used to model and evaluate alternative development scenarios. The method I propose uses the evaluation of urban form in a slightly different context, but the goal is similar: assisting planners with tools for more effective policy intervention. Second, because the method involves a layered, GIS-based analysis, it is geared to presenting alternatives rather than end-states. A variety of alternatives can be generated by using different measures of sustainable urban form. Planners devoted to the idea of sustainable urban form will need to work within existing parameters to advance their goals. Sustainable neighborhood form cannot be forced on anyone, least of all in places that have been historically resistant to land-use planning. The goal of sprawl retrofit is not to force sustainable urban form, but to look for sustainable urban potential and strengthen it wherever feasible. In a city dominated by sprawl, this can be legitimately cast as a way of providing more choice.

References Alexander C, 1965, ``A city is not a tree'' Architectural Forum 122(April) 58 ^ 62; (May) 58 ^ 61 Beatley T, 1999 Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities (Island Press, Washington, DC) Breheny M (Ed.), 1992 Sustainable Development and Urban Form (Pion, London) Burchell R W, Lowenstein G, Dolphin W R, Galley C, Downs A, Seskin S, Still K G, Moore T, 1998 Costs of Sprawl 2000 (National Academy Press, Washington, DC) Burchell R W, Downs A, McCann B, Mukherji S, 2005 Sprawl Costs: Economic Impacts of Unchecked Development (Island Press, Washington, DC) Burton E, 2002,``Measuring urban compactness in UK towns and cities'' Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 29 219 ^ 250 Carmona M, Heath T, Oc T, Tiesdell S, 2003 Public Places, Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design (Architectural Press, Oxford) Cervero R, 2009, ``Public transport and sustainable urbanism: global lessons'', in Transit Oriented Development: Making It Happen Eds C Curtis, J Renne, L Bertolini (Ashgate, Farnham, Surrey) pp 22 ^ 35 Cervero R, Kockelman K, 1997, ``Travel demand and the 3Ds: density, diversity and design'' Transportation Research Part D 2 199 ^ 219 Cervero R, Wu K-L, 1998, ``Sub-centring and commuting: evidence from the San Francisco Bay Area, 1980 ^ 90 Urban Studies 35 1059 ^ 1076 Chiras D, Wann D, 2003 Superbia! 31 Ways to Create Sustainable Neighborhoods (New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, BC) Christensen J, 2008 Big Box Reuse (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA) Clemente O, Ewing R, Handy S, Brownson R, Winson E, 2005 Measuring Urban Design Qualities: An Illustrated Field Manual (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, NJ) http://www.activelivingresearch.org/index.php/Tools and Measures/312 CNU, 2000 Charter of the New Urbanism Congress for the New Urbanism, Eds M Leccese, K McCormick (McGraw-Hill, New York) CNU, 2005 Malls Into Mainstreets: An In-depth Guide to Transforming Dead Malls Into Communities in cooperation with the US Environmental Protection Agency, Congress for the New Urbanism, Chicago, IL Collins W S, 2005 The Emerging Metropolis: Phoenix, 1944 ^ 1973 Arizona State Parks Board, Phoenix, AZ Colquhoun I, 2004 Design Out Crime: Creating Safe and Sustainable Communities (Architectural Press, London) Condon P M, Cavens D, Miller N, 2009 Urban Planning Tools for Climate Change Mitigation (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, MA) Davis J A, 1996, ``Interjurisdictional transport conflict in the Phoenix Metropolitan area: a study of the local state'' Cities 13(3) 175 ^ 185 Dittmar H, Ohland G, 2003 The New Transit Town: Best Practices in Transit-oriented Development (Island Press, Washington, DC) Dunham-Jones E,Williamson J, 2008 Retrofitting Suburbia: Urban Design Solutions for Redesigning Suburbs (John Wiley, Hoboken, NJ) Ellin N, 2006 Integral Urbanism (Routledge, New York)

976

E Talen

Ewing R, Bartholomew K, Winkelman S, Walters J, Chen D, 2008a Growing Cooler: The Evidence on Urban Development and Climate Change (Urban Land Institute, Washington, DC) Ewing R, Bartholomew K, Winkelman S, Walters J, Anderson G, 2008b, ``Urban development and climate change'' Journal of Urbanism 1 201 ^ 216 Farr D, 2008 Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design with Nature (John Wiley, Hoboken, NJ) Forsyth A, Hearst M, Oakes J M, Schmitz M K, 2008,``Design and destinations: factors influencing walking and total physical activity'' Urban Studies 45 1973 ^ 1996 Frey H, 1999 Designing the City: Towards a More Sustainable Urban Form (Taylor and Francis, London) Gammage G Jr, 2003 Phoenix in Perspective: Reflections on Developing the Desert (Herberger Center for Design Excellence, Tempe, AZ) Giles-Corti B, Donovan R J, 2003, ``Relative influences on individual, social environmental and physical environmental correlates of walking'' American Journal of Public Health 93 1583 ^ 1589 Gober P, 2006 Metropolitan Phoenix: Placemaking and Community Building in the Desert (University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA) Goodchild B, 1994, ``Housing design, urban form and sustainable development'' Town Planning Review 65 143 ^ 158 Grannis R, 2009 From the Ground Up: Translating Geography into Community through Neighbor Networks (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ) Greenwald M J, Boarnet M G, 2001, ``Built environment as a determinant of walking behaviour: analyzing non-work pedestrian travel in Portland, Oregon'' Transportation Research Record number 1780, 33 ^ 42 Hall J S, Karnig A K, 1984 Urban Villages/Council Districts: The Future Or Frustration? (Center for Public Affairs, Tempe, AZ) Handy S, Sallis J F,Weber D, Maibach E, Hollander M, 2008, ``Is support for traditionally designed communities growing? Evidence from two national surveys'' Journal of the American Planning Association 74 209 ^ 221 Hayden D, 2003 Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820 ^ 2000 (Pantheon, New York) Heath G W, Brownson R C, Kruger J, Miles R, Powell K E, Ramsey L T, Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2006, ``The effectiveness of urban design and land use and transport policies and practices to increase physical activity: a systematic review'' Journal of Physical Activity and Health 3 (supplement 1) S55 ^ S76 Hillier B, Hanson J, 1984 The Social Logic of Space (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge) ITE, 2005 Context Sensitive Solutions in Designing Major Urban Thoroughfares for Walkable Communities Institute of Transportation Engineers, Washington, DC Jabareen Y R, 2006, ``Sustainable urban forms: their typologies, models and concepts'' Journal of Planning Education and Review 26(1) 38 ^ 52 Jacobs A, Appleyard D, 1987,``Toward an urban design manifesto'' Journal of the American Planning Association 53(1) 112 ^ 120 Jacobs J, 1961 The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Vintage Books, New York) Jenks M, Dempsey N (Eds), 2005 Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities (Architectural Press, London) Jenks M, Burton E, Williams K (Eds), 1996 The Compact City: A Sustainable Urban Form? (E & FN Spon, London) Knaap G, Song Y, Nedovic-Budic Z, 2007, ``Measuring patterns of urban development: new intelligence for the war on sprawl'' Local Environment 12 239 ^ 257 Kunstler J H, 1994 The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America's Man-made Landscape (Free Press, New York) Larsen L, Alameddin D, 2007, ``The evolution of early Phoenix: valley business elite, land speculation, and the emergence of planning'' Journal of Planning History 6(2) 87 ^ 113 Leinberger C B, 2008 The Option of Urbanism: Investing in a New American Dream (Island Press, Washington, DC) Levine J, Inam A, Tong G, 2005, ``A choice-based rationale for land use and transportation alternatives evidence from Boston and Atlanta'' Journal of Planning Education and Research 24 317 ^ 330 Lukez P, 2007 Suburban Transformations (Princeton Architectural Press, Princeton, NJ) Lynch K, 1981 Good City Form (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA)

Sustainable urban form in unsustainable places

977

Marshall A, 2000 How Cities Work: Suburbs, Sprawl, and the Roads not Taken (University of Texas Press, Austin, TX) Mazmanian D A, Kraft M E,1999 Toward Sustainable Communities:Transition and Transformations in Environmental Policy (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA) Mehaffy M, Porta S, Rofe Y, Salingaros N, 2009, ``Urban nuclei and the geometry of streets: the `emergent neighborhoods' model'' Urban Design International 15(1) 22 ^ 46 Michelson W H, 1977 Environmental Choice, Human Behavior, and Residential Satisfaction (Oxford University Press, New York) Miles R, Song Y, 2009, `` `Good' neighborhoods in Portland, Oregon: focus on both social and physical environments'' Journal of Urban Affairs 31 491 ^ 509 Morrison Institute, 2008 Megapolitan: Arizona's Sun Corridor Morrison Institute for Public Policy, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ Moudon A V, Lee C, 2003, ``Walking and bicycling: an evaluation of environmental audit instruments'' American Journal of Health Promotion 18 21 ^ 37 Moudon A V, Lee C, Cheadle A D, Garvin C, Johnson D, Schmid T L, Weathers R D, Lin L, 2006, ``Operational definitions of walkable neighborhood: theoretical and empirical insights'' Journal of Physical Activity and Health 3 (supplement 1) S99 ^ S117 Murray A T, Davis R, 2001, ``Equity in regional service provision'' Journal of Regional Science 41 577 ^ 600 Newman P, Jennings I, 2008 Cities as Sustainable Ecosystems: Principles and Practices (Island Press, Washington, DC) Newman P W G, Kenworthy J R, 2006, ``Urban design to reduce automobile dependence'' Opolis: An International Journal of Suburban and Metropolitan Studies 2(1) 35 ^ 52 Norman G J, Nutter S K, Ryan S, Sallis J F, Calfas K J, Patrick K, 2006, ``Community design and access to recreational facilities as correlates of adolescent physical activity and body-mass index'' Journal of Physical Activity and Health 3 (supplement 1) S118 ^ S128 Nyden P, Maly M, Lukehart J, 1997, ``The emergence of stable racially and ethnically diverse urban communities: a case study of nine US cities'' Housing Policy Debate 8 491 ^ 533 Owen D, 2009 Green Metropolis: Why Living Smaller, Living Closer, and Driving Less are the Keys to Sustainability (Riverhead Hardcover, New York) Peterson R D, Krivo L J, Harris M A, 2000, ``Disadvantage and neighborhood violent crime: do local institutions matter? '' Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 37 31 ^ 63 Piedmont-Palladino S, Mennel T (Eds), 2009 Green Community (Planners Press, Chicago, IL) Popkin S J, Levy D K, Buron L, 2009, ``Has HOPE VI transformed residents' lives? New evidence from the HOPE VI panel study'' Housing Studies 24 477 ^ 502 Porter D R (Ed.), 2009 The Practice of Sustainable Development (Urban Land Institute,Washington, DC) Roseland M, 2005 Toward Sustainable Communities: Resources for Citizens and Their Governments (New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, BC) Rybczynski W, 2009, ``The green case for cities'' The Atlantic October, http://www.thatlantic.com/ doc/200910/solar-panels Salingaros N A, 1998, ``Theory of the urban web'' Journal of Urban Design 3 53 ^ 71 Sallis J F, Bauman A, Pratt M, 1998, ``Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity'' American Journal of Preventive Medicine 15 379 ^ 397 Scheer B, 2001, ``The anatomy of sprawl'' Places: A Forum of Environmental Design 14(2) 25 ^ 37 Scheer B, 2010 Typology and Urban Transformation (Planners Press, Washington, DC) Schipper J, 2008 Disappearing Desert: The Growth of Phoenix and the Culture of Sprawl (University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK) Sobel L, Bodzin S, 2002 Greyfields Into Goldfields: Dead Malls Become Living Neighborhoods (Congress for the New Urbanism, Chicago, IL) Song Y, Knaap G-J, 2004, ``Measuring urban form: is Portland winning the war on sprawl? '' Journal of the American Planning Association 70 210 ^ 225 Speir C, Stephenson K, 2002, ``Does sprawl cost us all? Isolating the effects of housing patterns on public water and sewer costs'' Journal of the American Planning Association 68 56 ^ 70 Steil L, Salingaros N, Mehaffy M, 2008, ``Growing sustainable suburbs: an incremental strategy for reconstructing sprawl'', in New Urbanism and Beyond: Designing Cities for the Future Ed. T Haas (Rizzoli, New York) pp 262 ^ 274 Stone Jr B, 2008, ``Urban sprawl and air quality in large UC cities'' Journal of Environmental Management 86 688 ^ 698 Tahchieva G, 2010 Sprawl Repair Manual (Island Press, Washington, DC)

978

E Talen

Talen E, 1998, ``Visualizing fairness: equity maps for planners'' Journal of the American Planning Association 64 22 ^ 38 Talen E, 2008 Design for Diversity: Exploring Socially Mixed Neighborhoods (Architectural Press, London) Trancik R, 1986 Finding Lost Space (Von Nostrand Reinhold, New York) Turner M A, Berube A, 2009 Vibrant Neighborhoods, Successful Schools: What the Federal Government Can Do to Foster Both (The Urban Institute, Washington, DC) ULI, 2009, ``Sustainable suburbs: developers' perspectives on transportation and compact growth'', 8 October, Urban Land Institute, Washington, DC, http://www.uli.org US Green Building Council, 2009 Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design ^ Neighborhood Development (LEED ^ ND) US Green Building Council, Washington, DC, http://www.usgbc.org/leed/nd/ van der Ryn S, Calthorpe P, 2008 Sustainable Communities: A New Design Synthesis for Cities, Suburbs and Towns (New Society Publisher, Gabriola Island, BC) Walsh B, 2009, ``Recycling suburbia'' Time 12 March Wheeler S M, 2005 Planning for Sustainability: Creating Livable, Equitable, and Ecological Communities (Routledge, London) Williams K, Burton E, Jenks M, 2000 Achieving Sustainable Urban Form (Spon Press, London) Yang Y, 2008, ``A tale of two cities: physical form and neighborhood satisfaction in metropolitan Portland and Charlotte'' Journal of the American Planning Association 74 307 ^ 323

2011 Pion Ltd and its Licensors

Conditions of use. This article may be downloaded from the E&P website for personal research by members of subscribing organisations. This PDF may not be placed on any website (or other online distribution system) without permission of the publisher.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Letter Request - Reclassification of Land - Iloilo City Council - NottinghamDocument2 pagesLetter Request - Reclassification of Land - Iloilo City Council - NottinghamHector Jamandre Diaz91% (11)

- General Trias CLUP Vol 1 Part 2 Comp Land Use Plan JJDocument45 pagesGeneral Trias CLUP Vol 1 Part 2 Comp Land Use Plan JJErvin Mark Suerte100% (7)

- Manure and FertilizerDocument8 pagesManure and FertilizerarjunPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Agriculture PracticeDocument81 pagesModern Agriculture PracticeH Janardan PrabhuPas encore d'évaluation

- Ann Statement FinalDocument2 pagesAnn Statement FinalAlex SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Ann Statement FinalDocument2 pagesAnn Statement FinalAlex SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Louis Theroux: 'I'm Not That Comfortable Doing Polemic' - Television & Radio - The GuardianDocument5 pagesLouis Theroux: 'I'm Not That Comfortable Doing Polemic' - Television & Radio - The GuardianblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- Screen Shot 2013-02-02 at 23.15.54Document1 pageScreen Shot 2013-02-02 at 23.15.54blaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- Bombay BitesDocument1 pageBombay BitesblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- Standard Tube MapDocument2 pagesStandard Tube MappastaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Pure Oil Pathfinder For A Century of Progress Exposition 1934 Northerly Island and Museum CampusDocument1 pagePure Oil Pathfinder For A Century of Progress Exposition 1934 Northerly Island and Museum CampusblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- Bombay BitesDocument1 pageBombay BitesblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- Thomas Cook Store FinderDocument20 pagesThomas Cook Store FinderblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- 2010map LDocument1 page2010map LblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- Forty HillDocument1 pageForty HillblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- Chicago HarbourDocument1 pageChicago HarbourblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- MCC Library's Chick Lit CollectionDocument5 pagesMCC Library's Chick Lit Collectionstell66100% (1)

- Geo Ex Pro 02 Geo TourismDocument5 pagesGeo Ex Pro 02 Geo TourismblaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- Mexican Market Eating MenuDocument1 pageMexican Market Eating MenublaaaaahhhhhPas encore d'évaluation

- The Effect of Soil Management On The Availability of Soil Moisture and Maize Production in DrylandDocument9 pagesThe Effect of Soil Management On The Availability of Soil Moisture and Maize Production in DrylandSahindomi BanaPas encore d'évaluation

- TillageDocument21 pagesTillageAbhilash DwivedyPas encore d'évaluation

- Law On Natural Resources: Prof. Owen Lynch, 63, Philippine Law JournalDocument66 pagesLaw On Natural Resources: Prof. Owen Lynch, 63, Philippine Law JournalNullus cumunisPas encore d'évaluation

- Planning QuestionersDocument11 pagesPlanning QuestionersJohnielyn Co - DeleonioPas encore d'évaluation

- Pocket - Parks-Urban Design PDFDocument6 pagesPocket - Parks-Urban Design PDFFadia Osman AbdelhaleemPas encore d'évaluation

- Organic Agricultural Production - A Case Study of Karnal District of Haryana State of IndiaDocument2 pagesOrganic Agricultural Production - A Case Study of Karnal District of Haryana State of Indiagosaindk6418100% (5)

- Draft HALA Rezoning Map For Admiral Urban VillageDocument1 pageDraft HALA Rezoning Map For Admiral Urban VillageWestSeattleBlog0% (1)

- Vetiver System For Soil and Water ConservationDocument75 pagesVetiver System For Soil and Water Conservationapi-3714517Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Rain Forests of GhanaDocument5 pagesThe Rain Forests of GhanaJane SorensenPas encore d'évaluation

- Agb.15 01 (Agr 405)Document4 pagesAgb.15 01 (Agr 405)Muhammad kalimullahPas encore d'évaluation

- Draft Force Inputs For Primary and Secondary Tillage Implements in A Clay Loam Soil - 2013 - Askari, KhalifahamzehghasemDocument6 pagesDraft Force Inputs For Primary and Secondary Tillage Implements in A Clay Loam Soil - 2013 - Askari, KhalifahamzehghasemVijay ChavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Use in North America vs. Europe: Outdoor SpaceDocument27 pagesUse in North America vs. Europe: Outdoor SpaceDB FasikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Terms of Reference for Construction of Chakdara-Kalam ExpresswayDocument37 pagesTerms of Reference for Construction of Chakdara-Kalam ExpresswayAli Nawaz BhattiPas encore d'évaluation

- Crop Production in The Limpopo ProvinceDocument34 pagesCrop Production in The Limpopo ProvincelexdeloiPas encore d'évaluation

- MFH Survey Provides Housing Data for Elderly and DisabledDocument167 pagesMFH Survey Provides Housing Data for Elderly and DisabledMPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Croix County Property Transfers For June 29-July 2 2020Document34 pagesSt. Croix County Property Transfers For June 29-July 2 2020Michael BrunPas encore d'évaluation

- Asteya Santiago Land ManagementDocument9 pagesAsteya Santiago Land ManagementAnn PulidoPas encore d'évaluation

- Topographic Map of WashingtonDocument1 pageTopographic Map of WashingtonHistoricalMapsPas encore d'évaluation

- Surveying ReviewerDocument2 pagesSurveying ReviewerRochelle Adajar-Bacalla100% (2)

- Topographic Map of Whites BayouDocument1 pageTopographic Map of Whites BayouHistoricalMapsPas encore d'évaluation

- Econ 193 Todaro Smith Chapter 7bDocument12 pagesEcon 193 Todaro Smith Chapter 7bडॉ. शुभेंदु शेखर शुक्लाPas encore d'évaluation

- DDO CodeDocument5 pagesDDO CodePartha BorahPas encore d'évaluation

- Shifting CultivationDocument2 pagesShifting CultivationmaxtorrentPas encore d'évaluation

- Topographic Map of Oyster CreekDocument1 pageTopographic Map of Oyster CreekHistoricalMapsPas encore d'évaluation

- Brunswick Forest Master Land Use PlanDocument1 pageBrunswick Forest Master Land Use PlanJohanna Ferebee Still0% (1)

- Grade 10 Unit 11 National ParksDocument3 pagesGrade 10 Unit 11 National Parkslavievan99Pas encore d'évaluation