Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Inclusion Position Paper

Transféré par

api-200858833Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Inclusion Position Paper

Transféré par

api-200858833Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Running head: INCLUSION: THE REALITY

Inclusion: The Reality Kate Barnard

Running head: INCLUSION: THE REALITY

Inclusion: The Reality Inclusion, a much-contested educational reform movement, is a slippery slope where it is hard to take an absolute stance. The idea of being able to welcome and include all students regardless of ability, behavior, or cognition is a noble one that in the rhetoric sounds right. Unfortunately, though, we do not live in the rhetoric. In schools today, a successful entirely inclusive classroom is not a reality, but an idealistic fantasy. Schools are not prepared or equipped to handle the demands of an entirely inclusive classroom, but I wish that they were. In an ideal world where school budgets were not fraying as a result of being stretched far, wide, and thinly and resources were limitless, inclusion would be the best model. How can an educational model that is, Essentially about belonging, participating, and reaching ones full potential in a diverse society, not convince anybody otherwise? (Odom, Buysse, & Soukakou, 2011, p. 247) Key to this description of an inclusive classroom is the measurement upon which students success and achievements would be measured; in regards to reaching their own potential. Individualization, embedded into a wonderfully diverse classroom community, would be a crucial cornerstone to the inclusive classroom; and if effectively done an ideal attribute of it. A diverse classroom that would successfully be able to cater to all students, and make all students feel equally worthy and important to the community of the classroom would be the ultimate preparation for the real-world after school. Successfully inclusive classrooms would Promote

Running head: INCLUSION: THE REALITY tolerance, understanding and respect for diversity which may extend even beyond the confines of the school to the community at large (Mowat, 2010, p. 632). If schools were able to raise a community of citizens that respected, understood, and accepted each other the implications for adulthood would mirror similar mindsets and allow for much more acceptance and understanding of diversity.

Not only would successfully inclusive classrooms benefit children both with and without disabilities in regards to acceptance and understanding, but in order for schools to have successfully inclusive classrooms, the quality of instruction in schools would be incredible (Odom et al., 2011, p. 247). In theory, successfully inclusive schools would, Become particularly skillful at responding to the individual characteristics of learners and therefore particularly effective at promoting learning, (Farrell, Dyson, Polat, Hutcheson & Gallannaugh, 2007 p. 142). This deliverance of high-quality instruction and corresponding Accommodations to practice and the gradual assimilation of values in keeping with the promotion of inclusion [would] enhance teacher professionalism, [encourage] teachers to become more reflective in their practice, to the benefit of all childrens learning and personal and social development. (Mowat, 2010, p. 632) While the universal access and participation, acceptance of diversity, and higher quality teaching and assessing that would come with successfully inclusive classrooms all make a strong argument in favor of inclusion, the reality is, in general, schools right now do not have the tools, resources, training, or knowledge of how to make entirely inclusive classrooms successful.

Running head: INCLUSION: THE REALITY The reasons are plentiful why inclusion is not a reality currently for schools;

the strain on teachers, the misalignment of inclusion goals with state standards, and the lack of resources for some of the toughest students. Teachers are often not considered when the inclusion debate arises, but they are a valid concern worth considering as they will be on the front line, sometimes even by themselves. A teacher I currently work with, young and otherwise healthy, developed a mild heart condition a couple of years ago, which had never been present before. She was diagnosed with this condition in the midst of what she considers to be the most difficult year of her life, due to her classroom population that year. The emotional strain for teachers to find more time for instruction is real, especially when teachers often spend so much of their time managing the students in their classroom, preventing blowouts, and making sure all students are attending, engaged, included, and understanding (Long, p.26). When teachers are busy exerting most of their efforts to a handful of students in the classroom, without proper resources and supports, time and energy for the rest of the students and instruction is shaved away. In a study of inclusive schools in the UK, Farrell et al. found that Students in more inclusive schools tend to attain at marginally lower levels than students in less inclusive schools, which was assumed to be due to the lack of availability the classroom teacher has when juggling a lack of resources, and demanding students (2007, p. 137). With these demanding students and lack of resources, teachers of inclusive classrooms would be expected currently to be able to provide adequate instruction to all students as would be evidenced by the standardized assessments which

Running head: INCLUSION: THE REALITY directly reflect the state curriculum standards. Teachers would not be rated,

recognized, or held accountable for how well they nurtured, included, or engaged all students (including some of the most difficult), but only instead on what pieces of the state standards all students had absorbed. All principles of an inclusive educational system would not be reflected in standardized testing, and an additional assessment method would need to be looked into in order to track all aspects of achievement for all students in an inclusive classroom. (Long) Lastly, schools (generally speaking) are without resources, tools, and training to effectively include and instruct some of the most difficult students. In a study of social outcomes in a Hong Kong elementary mainstream school, it was found that students in the inclusive group, meaning the students with special needs who were lower achieving, were found to rate themselves lower in social acceptance, school achievement, and social integration and higher in social rejection than the normal students in the school. (Bick-Har & See-Wai, 2005). This study also cited that Teachers perceptions of inclusive students achievement and behavioral competence were a mediating factor in peers perception of the inclusive students, (Bick-Har & See-Wai, 2005, p. 146). Here lies an issue with schools that are not properly trained to be inclusive. When students with special needs are included but made to feel alienated, rejected, and underachieving in classrooms, they have not been properly included! Why include all students if it cannot be done in a way that promotes social acceptance and understanding? Teachers need to be properly trained with ongoing professional development in order for inclusion to be seamless and effective.

Running head: INCLUSION: THE REALITY While inclusion is a model to strive for, currently The public school cannot be all things to students, and as of right now, there are some students whose

social/emotional and academic needs far exceed the resources and talent of a public school (Long, p. 39). If school budgets were bottomless, if teachers could be provided with effective and proper training to manage inclusive classrooms to benefit students and themselves, and if standards could be realigned to account for achievement, growth, and personal bests for all students then inclusion could be a realistic consideration. However, until then, full and absolute inclusion will be an educational and unrealistic fantasy.

Running head: INCLUSION: THE REALITY

References Bick-Har, L., & See-Wai, Y. (2005). Inclusion or Exclusion?--A Study of Hong Kong Students' Affective and Social Outcomes in a Mainstream Classroom. Educational Research For Policy And Practice, 4(2-3), 145-167.

Farrell, P., Dyson, A., Polat, F., Hutcheson, G., & Gallannaugh, F. (2007). Inclusion and achievement in mainstream schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 22(2), 131-145.

Long, N. (n.d). Inclusion: Formula for failure?. The Education Digest, 60(9), 2628. Mowat, J. (2010). Inclusion of pupils perceived as experiencing social and emotional behavioural difficulties (SEBD): affordances and constraints. International Journal Of Inclusive Education, 14(6), 631-648. doi:10.1080/13603110802626599

Odom, S. L., Buysse, V., & Soukakou, E. (2011). Inclusion for Young Children with Disabilities: A Quarter Century of Research Perspectives. Journal Of Early Intervention, 33(4), 344-356.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Rdep Final Assign 1Document14 pagesRdep Final Assign 1api-527229141Pas encore d'évaluation

- Luke Ranieri 17698506 Report Into Why Young People Misbehave in SchoolDocument8 pagesLuke Ranieri 17698506 Report Into Why Young People Misbehave in Schoolapi-486580157Pas encore d'évaluation

- Apst 4Document8 pagesApst 4api-553928009Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive EssayDocument5 pagesInclusive Essayapi-429836116Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pedagogy For Ple Assignment 3Document16 pagesPedagogy For Ple Assignment 3api-554337285Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment 1 FinalDocument7 pagesAssessment 1 Finalapi-473650460Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 1 Shuo Feng 19185558Document24 pagesAssignment 1 Shuo Feng 19185558api-374345249Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reid 18342026 InclusiveDocument6 pagesReid 18342026 Inclusiveapi-455453455Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Assessment 3Document16 pagesInclusive Assessment 3api-554472669100% (1)

- ReflectionDocument5 pagesReflectionapi-408471566Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pple Assessment 2 Reflection - Philosophy of Classroom ManagementDocument16 pagesPple Assessment 2 Reflection - Philosophy of Classroom Managementapi-331237685Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment 3Document15 pagesAssessment 3api-476398668Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment 1 Inclusive EducationDocument10 pagesAssessment 1 Inclusive EducationB NovPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 102082 Philosophy of Classroom Management Document R 1h208Document17 pagesUnit 102082 Philosophy of Classroom Management Document R 1h208api-374359307Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment 2 Inclusive EducationDocument6 pagesAssessment 2 Inclusive Educationapi-478766515Pas encore d'évaluation

- TEAC7001 Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Autumn 2022Document15 pagesTEAC7001 Aboriginal & Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Autumn 2022Salauddin MeridhaPas encore d'évaluation

- RTL Assessment 2Document12 pagesRTL Assessment 2api-332715728Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment 2 - Gabriella Talarico Lit Review Consent Action ProtocolDocument13 pagesAssessment 2 - Gabriella Talarico Lit Review Consent Action Protocolapi-486388549Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kumarviganesh 102746Document7 pagesKumarviganesh 102746api-478576013Pas encore d'évaluation

- CTL ReflectionDocument7 pagesCTL Reflectionapi-357686594Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bhorne 17787840 Reflectionassessment2Document7 pagesBhorne 17787840 Reflectionassessment2api-374374286Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Education Assignment 1Document11 pagesInclusive Education Assignment 1api-357662510Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ppce Self Reflection FormDocument2 pagesPpce Self Reflection Formapi-435535701Pas encore d'évaluation

- Pedagogy For Positive Learning Environment Report2Document6 pagesPedagogy For Positive Learning Environment Report2api-408471566Pas encore d'évaluation

- Improve Classroom Communication SkillsDocument5 pagesImprove Classroom Communication SkillsClaudia YoussefPas encore d'évaluation

- Summer 2017-2018 Assessment1Document10 pagesSummer 2017-2018 Assessment1api-332379661100% (1)

- Teaching Philosophy EdfdDocument11 pagesTeaching Philosophy Edfdapi-358510585Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inc Assignment 1 3Document26 pagesInc Assignment 1 3api-527229141Pas encore d'évaluation

- Alisha Rasmussen - 19059378 - Researching Teaching and Learning 2 Assessment 2Document22 pagesAlisha Rasmussen - 19059378 - Researching Teaching and Learning 2 Assessment 2api-466919284Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2H2018Assessment1Option1Document7 pages2H2018Assessment1Option1Andrew McDonaldPas encore d'évaluation

- 2h2018assessment1option1Document9 pages2h2018assessment1option1api-317744099Pas encore d'évaluation

- rtl2 Assessment 3Document59 pagesrtl2 Assessment 3api-485489092Pas encore d'évaluation

- PLP Proforma Shannon MolloyDocument14 pagesPLP Proforma Shannon Molloyapi-512922287Pas encore d'évaluation

- CTL ReflectionDocument4 pagesCTL Reflectionapi-464786469Pas encore d'évaluation

- rtl2 Assignment 2 1Document9 pagesrtl2 Assignment 2 1api-332423029Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wsu Tpa D Jordan 18669233 pp2Document76 pagesWsu Tpa D Jordan 18669233 pp2api-459576779Pas encore d'évaluation

- Suma2018 Assignment1Document8 pagesSuma2018 Assignment1api-355627407Pas encore d'évaluation

- Adam Duffey Red Hands Cave Lesson 10Document7 pagesAdam Duffey Red Hands Cave Lesson 10api-328037285Pas encore d'évaluation

- Personal Reflection Designing TeachingDocument6 pagesPersonal Reflection Designing Teachingapi-380738892Pas encore d'évaluation

- Action Research Assessment 2Document14 pagesAction Research Assessment 2api-554490943100% (2)

- 2h 2018 Assessment1 Option2Document7 pages2h 2018 Assessment1 Option2api-355128961Pas encore d'évaluation

- 18897803Document2 pages18897803api-374903028Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment Cover Sheet: Imran Ali Tamer 18019647Document17 pagesAssignment Cover Sheet: Imran Ali Tamer 18019647api-369323765Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Education Case StudyDocument12 pagesInclusive Education Case Studyapi-321033921100% (1)

- Inclusive Education For Students With Disabilities - Assessment 1Document4 pagesInclusive Education For Students With Disabilities - Assessment 1api-357683310Pas encore d'évaluation

- Professional Practice ReflectionDocument9 pagesProfessional Practice Reflectionapi-534444991Pas encore d'évaluation

- Irvin Cisneros Assignment 2 Biology FinalDocument20 pagesIrvin Cisneros Assignment 2 Biology Finalapi-3576852070% (1)

- Assignment 1: Aboriginal Education (Critically Reflective Essay)Document11 pagesAssignment 1: Aboriginal Education (Critically Reflective Essay)api-355889713Pas encore d'évaluation

- CTL Final Critical ReflectionDocument6 pagesCTL Final Critical Reflectionapi-368798504Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Assignment 2Document12 pagesInclusive Assignment 2api-435738355Pas encore d'évaluation

- Aboriginal Culturally Responsive PedagogiesDocument2 pagesAboriginal Culturally Responsive Pedagogiesapi-357683351Pas encore d'évaluation

- PLP Edfd462 Assignment 1Document12 pagesPLP Edfd462 Assignment 1api-511542861Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wilman Rebecca 17325509 Educ4001 Assessment 2Document15 pagesWilman Rebecca 17325509 Educ4001 Assessment 2api-314401095100% (1)

- Assessment One - R Jones - Id 110232780 15Document10 pagesAssessment One - R Jones - Id 110232780 15api-465726569Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 1 - 102085Document10 pagesAssignment 1 - 102085api-357692508Pas encore d'évaluation

- Barriers Faced by Parents with Disabilities in School CommunitiesDocument6 pagesBarriers Faced by Parents with Disabilities in School CommunitiesQueenPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng2 Assign1 TemplateDocument8 pagesEng2 Assign1 Templateapi-527229141Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 1 LastDocument6 pagesAssignment 1 Lastapi-455660717Pas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum & Assessment: Some Policy IssuesD'EverandCurriculum & Assessment: Some Policy IssuesP. RaggattÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- Empowering Parents & Teachers: How Parents and Teachers Can Develop Collaborative PartnershipsD'EverandEmpowering Parents & Teachers: How Parents and Teachers Can Develop Collaborative PartnershipsPas encore d'évaluation

- Iep MTG ObservationDocument1 pageIep MTG Observationapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- KG Progress Monitoring2Document2 pagesKG Progress Monitoring2api-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Compare Contrast SBTDocument1 pageCompare Contrast SBTapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Interview AnalysisDocument8 pagesInterview Analysisapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Vocab Progress MonitoringDocument1 pageVocab Progress Monitoringapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Lesson Plan Chap 5 Feb 4Document5 pagesReading Lesson Plan Chap 5 Feb 4api-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- DW Notice of Meeting Notes Eval ReportDocument14 pagesDW Notice of Meeting Notes Eval Reportapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Markus PM GraphDocument1 pageMarkus PM Graphapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Child Count InfoDocument1 pageChild Count Infoapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Davin Academic EvalDocument5 pagesDavin Academic Evalapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- KG Progress Monitoring2Document2 pagesKG Progress Monitoring2api-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Graces Vocab ProgressDocument1 pageGraces Vocab Progressapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- KG Writing Graphic Organizer and ParagraphDocument3 pagesKG Writing Graphic Organizer and Paragraphapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Play Ways Complete UnitDocument54 pagesPlay Ways Complete Unitapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mike Towl EvalDocument5 pagesMike Towl Evalapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Exit Slip Template MKDocument1 pageExit Slip Template MKapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Visual 3 Gates of Special EducationDocument2 pagesVisual 3 Gates of Special Educationapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- MK Math Goal 1 Progress MonitoringDocument1 pageMK Math Goal 1 Progress Monitoringapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Visual Basic Skill AreasDocument2 pagesVisual Basic Skill Areasapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Power StandardsDocument1 pagePower Standardsapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Lesson Plan Feb 11 Compare SPD DateDocument5 pagesReading Lesson Plan Feb 11 Compare SPD Dateapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

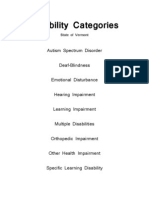

- Visual Disability CategoriesDocument2 pagesVisual Disability Categoriesapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Writing Sample KGDocument1 pageWriting Sample KGapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Deidentified MarblesDocument1 pageDeidentified Marblesapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Trash Can MathDocument1 pageTrash Can Mathapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Sheet 1Document1 pageLearning Sheet 1api-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- MK Math Lesson Sept 19Document1 pageMK Math Lesson Sept 19api-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mission StatementDocument1 pageMission Statementapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Graphic OrganizerDocument1 pageGraphic Organizerapi-200858833Pas encore d'évaluation

- Delay SpeechDocument8 pagesDelay Speechshrt gtPas encore d'évaluation

- GRADE 11 SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL ACCOUNTING DAILY LESSONDocument3 pagesGRADE 11 SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL ACCOUNTING DAILY LESSONDorothyPas encore d'évaluation

- Student Motivation ScaleDocument26 pagesStudent Motivation ScaleScholar WinterflamePas encore d'évaluation

- Getting To Know SomeoneDocument4 pagesGetting To Know SomeonePatricia PerezPas encore d'évaluation

- Kendall Instructional PlaybookDocument11 pagesKendall Instructional Playbookapi-653182023Pas encore d'évaluation

- Competency 5 Communication SkillsDocument5 pagesCompetency 5 Communication Skillsapi-281319287Pas encore d'évaluation

- Immaculata Lesson Plan Alyssa Brooks Subject: Writing - Expressive Writing Grade: Second I. ObjectivesDocument2 pagesImmaculata Lesson Plan Alyssa Brooks Subject: Writing - Expressive Writing Grade: Second I. Objectivesapi-272548014Pas encore d'évaluation

- Summer Reading CampDocument5 pagesSummer Reading CampJeyson B. BaliosPas encore d'évaluation

- Application FormDocument3 pagesApplication FormMurdoch Identity Project GroupPas encore d'évaluation

- 50th 6-29-16 BookDocument60 pages50th 6-29-16 BookJim LeiphartPas encore d'évaluation

- LAW2 Syllabus FINALDocument10 pagesLAW2 Syllabus FINALMaria SalongaPas encore d'évaluation

- B.SC Physics Sem 5 6Document31 pagesB.SC Physics Sem 5 6vikasbhavsarPas encore d'évaluation

- Quota SamplingDocument6 pagesQuota SamplingKeking Xoniuqe100% (1)

- GLAK Development GuidelinesDocument63 pagesGLAK Development GuidelinesZyreane FernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Computer Skills Module 5 Intro To ExcelDocument14 pagesBasic Computer Skills Module 5 Intro To ExcelmylespagaaPas encore d'évaluation

- CBT POA and ROEDocument4 pagesCBT POA and ROEDzaky AtharizzPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample: Selective High School Placement Test Z9936 Thinking Skills - Answer SheetDocument1 pageSample: Selective High School Placement Test Z9936 Thinking Skills - Answer SheetNatasha RajfalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Prospectus For Selection Of: Graduate Marine Engineers (Gme), BatchDocument11 pagesProspectus For Selection Of: Graduate Marine Engineers (Gme), BatchtigerPas encore d'évaluation

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in Math-Grade 1Document4 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in Math-Grade 1Ferdinand MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- PBL - Nor Azuanee Mukhtar Mp101439Document16 pagesPBL - Nor Azuanee Mukhtar Mp101439Azuanee AzuaneePas encore d'évaluation

- Sample MT 1 MckeyDocument6 pagesSample MT 1 MckeytortomatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Emcee Script For Closing ProgramDocument3 pagesEmcee Script For Closing ProgramKRISTLE MAE FRANCISCOPas encore d'évaluation

- Vice - Principal Evaluation Report - Dana SchaferDocument4 pagesVice - Principal Evaluation Report - Dana Schaferapi-294310836Pas encore d'évaluation

- Effective ListeningDocument17 pagesEffective ListeningShafiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching & Learning BiologyDocument178 pagesTeaching & Learning BiologyobsrvrPas encore d'évaluation

- Feasibility of Restaurant in National Road, Barangay HalayhayinDocument15 pagesFeasibility of Restaurant in National Road, Barangay HalayhayinJhasper ManagyoPas encore d'évaluation

- Content Magnets 3717Document5 pagesContent Magnets 3717api-351279190Pas encore d'évaluation

- Automated Daily Lesson Log 2020-2021Document15 pagesAutomated Daily Lesson Log 2020-2021Ra MilPas encore d'évaluation

- DLL CNFDocument2 pagesDLL CNFMARIA VICTORIA VELASCOPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan in Media and Information Literacy: Mil11/12Lesi-Iiig-19Document2 pagesLesson Plan in Media and Information Literacy: Mil11/12Lesi-Iiig-19לארה מאי100% (1)