Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A Balanced Approach To Esl

Transféré par

api-219027126Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Balanced Approach To Esl

Transféré par

api-219027126Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A Balanced Approach to ESL/EFL reading instruction Learning to read in any language is a complex skill that requires a strong foundation

of bottom-up skills and top-down skills. For the ESL/EFL student, learning to read in English can be exceptionally difficult due to its highly inconsistent grapheme-phoneme relationships. ESL/EFL students from differing alphabetic backgrounds such as logographic, syllabic or nonRoman alphabets may face additional challenges. These students may lack strong alphabetic processing skills and, as a result, may struggle with slow, inefficient and labored reading. Current, typical ESL/EFL reading instruction focuses on developing top-down strategies such as vocabulary and fluency building, skimming, scanning and comprehension strategies with little focus given to developing the foundational bottom-up word building skills of phonological awareness and phonics. Bottom-up strategies include understanding letter-sound correspondences, prefixes, root words and sight words (as well as grammar and syntax). An ESL/EFL reading course that incorporates the development of vocabulary, comprehension and fluency as well as components of phonemic awareness and phonics instruction will include all of the necessary components required for fluent, efficient reading and will meet the needs of ESL/ESL students lacking in alphabetic processing skills that the traditional reading curricula do not. Traditional ESL reading curricula Traditional ESL/EFL reading courses primarily address the development of top-down reading skills such as vocabulary, comprehension and fluency building strategies. A typical lesson might focus on a text passage, with skimming, scanning, summarizing exercises, comprehension and vocabulary building exercises, written and or speaking practice, bottom-up skills might be addressed with grammar or syntax exercises. Level differences are typically

addressed by the lexical, sematic, syntactic or contextual complexity of texts as well as the complexity of comprehension, inference and writing exercises. An example of a typical, beginning level reading course using the Active Skills for Reading: Book 1, (Anderson, 2003) begins with a needs analysis Are you an ACTIVE reader?, 10 questions follow for the student to do a basic self-evaluation, such as How much time do you spend each day reading in your native language? and Do you enjoy reading in English? (Anderson, 2003, pg vi). Lesson 1, with an approximately 200-word text entitled Food Facts, is of general interest, addressing food likes and dislikes, healthy and unhealthy eating habits. The language used contains present tense verbs, gerunds, simplified vocabulary and syntactic structures. Pre-reading exercises include schema activation questions for pair-work. Comprehension multiple-choice questions, discussion and vocabulary skill building exercises follow the text with a wrap-up pair-work exercise to practice speaking skills and to recycle newly introduced vocabulary words. Read Ahead, Reading and Life Skills Development Level 2 is a reading series that aims to teach the learner reading skills to function in real life. Following a traditional approach each lesson introduces a new theme. The themes of this series present life skills such as: Safety Matters, Voting Counts and Employment Counts(McEntire,2004). Each chapter is prefaced with previewing exercises for schema activation and new vocabulary. The text follows with comprehension questions and writing exercises. Of the five critical skills for reading, exercises and activities for vocabulary, comprehension and fluency development are taught through general interest/life skill topics. A typical beginning ESL/EFL English, textbook, Grammar and Beyond (Reppen, 2012), is a grammar-based series with an emphasis on the application of the structures to academic

writing. Structures are presented in context of real-life situations. Lesson 1 of Level 1, Statements with Present of Be(Reppen),is an approximately 125-word text in the form of a conversation. Informal language is used focusing on greetings; verbs are in the present tense, sentence structure models real-life conversation. The text is followed by a grammar presentation, pair-work to practice speaking skills and wraps up with writing exercises. The skills focused on in these three typical beginning reading and language instruction texts, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension, are critical to ESL instruction, none incorporate the PA or phonic components into their curriculum. To incorporate field knowledge, I observed two reading classes, at the UIC Tutorium and at a Vocabulary Skills class at the English Language Services (ELS) and interviewed both teachers regarding reading instruction. The UIC Tutorium students were intermediate-level from a variety of L1 backgrounds, the course used the Active Skills for Reading: Book 4 (Anderson). The focus of the lesson was a newly introduced text/topic, goals included: new vocabulary acquisition, better understanding of previously taught parts of speech, improved skimming and scanning skills. A pre-reading activity included predicting text content and discussion/analysis of the text topic, 1-minute skimming was followed by discussion of information gleaned and a class discussion of individual strategies used. New vocabulary was discussed with students or teacher providing definitions. While-reading and after-reading activities included individual reading, summarizing in writing and a syntax/grammar exercise recycling newly learned vocabulary. The Vocabulary Skills class at the ELS used similar, though more advanced, textbook. A newly introduced text had been introduced in the previous class. A pre-reading activity consisted of a class discussion to predict text content and to share individual background knowledge and

experiences relating to the topic. Fluency practice followed with individuals reading passages of the text aloud. The class wrapped up with comprehension work to discuss the main ideas in the text. The second days activities consisted of pair-work and class discussion of unfamiliar vocabulary words and of strategies for guessing meaning. Strategy ideas proposed by students and teacher, including identifying parts of speech, adjacent words, main ideas, character relationships, were discussed and boarded for reference. Vocabulary definitions were not provided by the teacher, rather students were encouraged to use the various strategies to guess meanings. The class wrap-up was a discussion of the strategies. An after-reading activity was assigned as homework, students were to recycle the newly learned vocabulary in a 5-sentence paragraph. (It was an impressive class to watch!). Both classes focused primarily on top-down strategies of comprehension, vocabulary and fluency exercises with less focus on grammar and syntax. Neither decoding nor word skill instruction was incorporated, perhaps due to the lack of need or due to syllabus design. In her paper Reading in recent ELT coursebooks, Rosa Maria Mera Rivas reviewed the current ESL reading instructional components contained in typical adult (age 15+) coursebooks for intermediate levels and above, The analysis focuses on the attempts to develop both lowerlevel processing skills and higher-level comprehension and reasoning skills in EFL learners (Rivas). The instruction found in these texts typically suggests building top-down and bottom-up skills in the three-phase approach to reading instruction. Attention is given to the development vocabulary and syntactic knowledge, comprehension and writing skills through pre-reading, while-reading and post-reading activities. Pre-reading activities also included schema activation, vocabulary development and trying to arouse student interest. Additional while-reading activities

included direct, indirect and reference questions. Post-reading activities included summarizing, discussions and writing compositions. What the research says about reading instruction While bottom-up word analysis instruction is missing in the current typical ESL reading curriculum instruction, much research has been done to demonstrate the importance of a balanced approach to ESL reading instruction, one which includes the five critical components of reading instruction: vocabulary, comprehension, fluency, phonemic awareness and phonics. In 2000, the National Institute for Child Health and Development (NICHD), mandated by Congress, conducted a comprehensive, evidence-based review of research on how children learn to read. The National Reading Panel (NRP), the panel established to review the research, determined that a balanced approach to reading instruction is most effective. A combination of top-down and bottom-up methods that includes: phonemic awareness, phonics, guided oral reading, vocabulary and comprehension strategies should be incorporated into curriculum design. The importance of strong PA skills was noted, Overall the findings showed that teaching children to manipulate phonemes in word was highly effective under a variety of teaching conditions with a variety of learners across a range of grade and age levels and that teaching phonemic awareness to children significantly improves their reading more than instruction that lacks any attention to phonemic awareness (NRP, 2006, pg. 1). The NRP states that while, Phonemic awareness instruction provides children with the essential foundational knowledge in the alphabetic system, it is one necessary instructional component within a complete and integrated reading program (NRP, 2006, pg.2). In addition to phonemic awareness instruction, phonics instruction must be included to give learners the ability to apply their reading skills which in turn facilitates comprehension and fluency. Comprehension

is, of course the essence of reading (NRP, 2006, pg.8), it is developed through the ability to accurately and fluently decode words, developed vocabulary and strong comprehension strategies. Vocabulary should be taught indirectly and directly, repetition and multiple exposures to words, rich and engaging texts are all vital to vocabulary learning (NPR, 2006, pg. 9). Comprehension is enhanced when the learner can actively engage with the text and relate personal experience. Teaching a combination of reading comprehension strategies such as monitoring, graphic and semantic organizers, question answering, story structuring, and summarization, was found most effective. The importance of grammar and syntax instruction was not review in this meta-analysis though it will be addressed below. Research has demonstrated that ESL learners require a similar balanced approach to reading instruction. (Adams and Burt, 2002, Jones, 1996, Florez & Burt, 2001) In their research study, The Development of Reading in Children Who Speak English as a Second Language, (2003), Leseaux & Siegel investigated the effectiveness of a reading program designed for children with little or no reading proficiency in their L1. In this school district, all students received a balanced approach to literacy instruction that included phonemic awareness instruction and systematic phonics instruction, three to four times a week for twenty minutes, in small group activities in addition to independent activities such as cooperative story writing and journal writing. The results of this study found that the development of reading skills for ESL and L1 learners was very similar. The authors suggest that ESL and L1 students respond positively and similarly to balanced literacy instruction that includes phonemic awareness instruction and to direct teaching at the specific needs of the learners, Systematic student assessment in kindergarten and explicit skills instruction are critical to a model of early reading acquisition for children from diverse linguistic backgrounds (Leseaux & Seigel, 2003, pg.1018).

L1 and ESL students alike benefitted from a balanced approach to reading instruction, both groups showed significant gains in measures of lexical access, syntactic awareness, phonological processing, memory and spelling. In their book Reading and Adult English Language Learners, A Review of the Research, Burt, Peyton & Adams (2004) detail an exhaustive review of twenty years of research on adult ESL reading and provide suggestions for adult ESL reading instruction. The review of the existing research confirms the importance of vocabulary, fluency and comprehension strategies, phonemic awareness and phonics skills for adult ESLs/EFLs and the importance of the incorporation of all five into reading curricula. (Koda, 1999, Jones, 1996, Strucker, 1997, 2002, Kruidenier, 2002). The authors note that the factors that influence the literacy development of adult ESLs are perhaps even more complex than those of children learning to read, Learners who are highly literate in their L1 and who also have high levels of L2 proficiency will be more likely to transfer their L1 reading strategies to their L2 reading. When learners have reached the point that their metacognitive knowledge (from their L1) can support their L2 reading, they should be taught how to apply that knowledge to reading tasks (Burt et al.(2004) pg.15). The authors discuss interactive models for reading comprehension that readers use to derive meaning from text. These interactive models posit that both top-down and bottom-up strategies work together in the process of engaging with text. Adult ESL/EFL readers should be taught to incorporate top-down strategies, such as inferencing, background knowledge and predicting from their L1 reading that can support their L2 reading, and scaffolded with bottom-up word analysis strategies. A balanced approach to reading instruction must be incorporated into syllabus design to provide the ESL/EFL with the necessary skills.

Students with unmet needs ESL/EFL reading students will benefit from a curriculum that incorporates all five necessary components for reading and that develops strategies in all areas. A solid knowledge of the English sound-symbol correspondences is a critical bottom-up foundation skill that must be developed for fluent, efficient reading. Beginning-level students will benefit from a balanced curriculum at the earliest stages. Additionally, it is importance to identify students who may have been placed in higher-level courses based on developed speaking and listening skills but may still struggle with slow and inefficient reading due to undeveloped alphabetic processing skills. For these students supplementary reading instruction in PA and phonics will develop these bottom-up reading strategies. In addition to the students whose L1 is Roman-alphabetic and needs to learn the sound-symbol correspondences, students whose L1 is non-Roman alphabetic, logographic or syllabic may need to develop new processing skills necessary for fluent, automatic reading of the English language. A Balanced Approach to Reading Instruction for Children In their book, Research-Based Methods of Reading Instruction for English Language Learners, Grades K-4 (2007) Sylvia Linan-Thompson and Sharon Vaughn cite the findings of research that demonstrate the importance of a balanced approach to ESL reading instruction and provide lessons and activities for teaching ESL children that incorporate the critical elements (Linan-Thompson,Vaughn, 2007) of reading development: PA, phonics and word study, fluency, vocabulary instruction and comprehension. The authors address the lack of available reading instruction resources for the greatly growing ELL community in America and provide instructional methods based on the limited (& much needed) existing research for this

population. They stress that teaching strategies that develop higher-order skills and basic skills (Linan-Thompson,Vaughn, 2007) must be incorporated in daily lesson plans for students even at early proficiency levels. Vocabulary development is crucial for reading comprehension, explicit strategies must be taught to encourage the use of the same cognitive strategies the ESL student uses in their L1. Recommended practices for teaching vocabulary include: explicit instruction, implicit instruction, the use of multimedia, capacity building and association methods. Recommended practices for teaching comprehension skills include: before, during and afterreading activities, questioning, using background knowledge and summarization. To develop fluency, the authors cite the critical elements that have been documented to improve reading fluency including providing explicit models and multiple opportunities to practice. While reading courses typically focus on the higher-order skills many do not address the basic skills. Explicit PA skills must be taught, ESLs may benefit from L1 transfer of skills but need explicit instruction in the sounds of English as well as new orthographic patterns. With improved PA skills, Improved fluency and automatic word recognition will allow students to focus on understanding and analyzing the text (Linan-Thompson, Vaughn, 2007, pg. 5). The ultimate attainment of comprehension can be mastered by a balanced teaching approach that incorporates all five skills. A Proposed Design for an Adult ESL/EFL Reading Course Who? While research has demonstrated the importance of incorporating PA and phonics instruction into reading curricula for adult ESL/EFL learners it is, nonetheless, lacking from current typical reading curricula. A comprehensive approach will have benefits across levels.

From the novice, L1 nonliterate student with obvious immediate needs to the more advanced learner, There is evidence indicating that even advanced English learners whose native language is written with the Roman alphabet can have difficulty with phonological processing in English and need to be taught to decode to match letters and sounds (Burt et al., 2004, pg.26). The ESL student who has acquired a strong understanding of the Roman-alphabetic principal and has developed strong bottom-up reading strategies may, in fact, require less instruction of the English sound-symbol correspondences and more focus on the top-down strategies. However, some ESL students from differing alphabetic backgrounds may not acquire these skills as easily and will need more direct instruction in the foundation building of these bottom-up skills. As mentioned above, ESL/EFL students from Roman-alphabetic languages may also need direct instruction in and practice with the English phoneme-grapheme system. These learners will all benefit from a reading course that incorporates PA and phonics into a balanced curriculum which includes the teaching of vocabulary, fluency and comprehension strategies. Needs assessment A needs assessment done before instruction begins will help determine the needs of the individual student, guide syllabus design and group students into appropriate levels. While oral language skills are often used in placement tests, research has demonstrated that oral language skill assessments are not reliable indicators of reading ability (Leseaux & Seigel, 2003, Koda, 1999, Wilson 1983, Stuart, 2002) and that measures of phonemic awareness are better indicators and should be used, discussed below). Needs assessment such as The Test of Silent Word Reading Fluency (TOSWRF) and the Word Identification and Spelling (WIST) or the SoundSymbol Knowledge are commercially available assessments used to identify strengths and

weaknesses in word identification, spelling and grapheme-phoneme knowledge. See Appendix A. A more cost-effective assessment (I have this test) to the TOSWRF and WIST ($163 and $280 respectively) would be, a modified version of the Wilson Assessment of Decoding and Encoding (WADE). Developed for L1 English speakers with reading deficits, the WADE can be adapted for ESL students (specifically removing nonsense words). The WADE assessment is intended to measure grapheme and phoneme knowledge, decoding and encoding skills, syllable and sight word knowledge. The in-person, individual assessment requires approximately 25 minutes per student and provides detailed individual needs assessment. The test, ideally administered by the teacher, has three sections: Section 1 -sounds : the student is to read from a list of isolated graphemes and name the corresponding sound, Section 2 -reading: the student is to read from a list of progressively more difficult words in and from a list of sight words in isolation, Section 3- spelling: the student writes the word, sight word or sentence dictated. This test can also be used as a post-test to measure achievement. Appendix B provides an example of the test and the administrators scoring form. If this administration is not practical, the online survey will provide a less detailed, general overview of individual strengths and weaknesses in grapheme-phoneme awareness by testing receptive, aural knowledge. Via an online survey, http://cindyanner.polldaddy.com/s/initial-assessment students will listen to an audio recording of words (repeated twice) and chose the correct option from three multiple choice answers. Another survey might be allow the students to provide more details, providing output that will provide a needs analysis in its responses as well as the spelling: http://www.surveymonkey.com/s/NTPHC36 Ongoing individual assessment must be done in class with daily dictation exercises. These exercises should test knowledge of graphemes and phonemes in isolation, fluent decoding and

encoding of phonetically regular words in isolation and in sentences and sight word knowledge. See Appendix C for an example of a daily dictation exercise. A needs assessment done with my high school students (at-risk L1 and L2 English) was a reading from Fox in Sox by Dr. Seuss Book. The student read a section of the book as an oral assessment, Here's an easy game to play. Here's an easy thing to say.... New socks. Two socks. Whose socks? Sue's socks. Who sews whose socks? Sue sews Sue's socks. Who sees who sew whose new socks, sir? You see Sue sew Sue's new socks, sir. That's not easy, Mr. Fox, sir (Seuss, 1969) While it worked very well with this population (in fact, surprisingly well), a trial would need to be done to check how appropriate it would be for a college-aged student.

A Proposed Design for an Adult ESL/EFL Reading Course Where and How? While research has shown that phonemic awareness training and phonics instruction should be included into ESL reading courses it typically is not. Jones suggests that this may be in part due to lack of teacher training, Lack of research into this approach (integrating PA into instruction) for the limited literacy adult suggests to me that phonics generalizations are not incorporated into adult ESL instruction because teachers cannot articulate basic phonics generalizations. A test given to 83 prospective and practicing NS/NNS teachers of ESL/EFL

bears out my hyphothesis (Jones, 1996, pg 12). (In this test, teachers were given a list of phonetically related words and asked to articulate generalizations. Only the elementary teachers working with phonics programs were able to quickly explain rules). Burt et al. assert that the lack of comprehensive reading programs is due to a lack of research, While there is little research on the patterns of literacy development of adults learning English, there is even less on best practices for teaching literacy to this population (Burt et al., 2005, pg 39)) and suggest the incorporation of the five components based on the existing research. Birch (2007) discusses the debate among teachers regarding the best methods for reading instruction, teaching exclusively bottom-up strategies or top-down strategies and instead proposes an approach that incorporates both. This approach emphasizes the interactive nature of reading and the range of processing skills that must be developed. Eskey (1988), also proposes interactive approaches to ESL reading instruction, stressing the importance of phonemic awareness phonics skills, Despite the emergence of interactive models, I am concerned that much of the second language reading continues to exhibit a strongly top-down bias and continues We must not, I believe, lose sight of the fact that language is a major problem in second language reading, and that even educated guessing at meaning is not a substitute for accurate decoding (Eskey, 1988, pg 97). Birch also discuss that while recent ESL reading texts acknowledge the importance of the bottom-up process, their attention is still firmly on the top-down strategies with the belief that the development of higher-level skills will supplement deficiencies at the lower-level. Comprehensive approaches can and should be developed and may, as suggested by Jones, require additional teacher training. Interestingly, in a recent class presentation given by the director of the UIC Tutorium, she stated that spelling skills were not a focus of their ESL

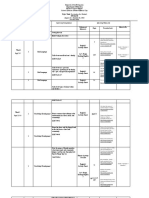

program as students write (and will always write) on computers and can therefore rely on spellcheck. A traditional reading course can be adapted to incorporate phonemic awareness and phonics instruction. A basic overview of such a course might be: Students: college-aged students in a university setting enrolled in an ESL program with a separate reading course. ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines: Mid-Intermediate or above speaking and listening skills Novice-High to Intermediate-Low level reading. Students preparing to take the TOFEL exam for American university studies. Given the increased enrollment of Saudi students at the UIC Tutorium, I imagine a course that would address that L1 Arab population. Class size: 5-10 students. Goal of class: ACTFL Guidelines: Intermediate High level reading. An adaptation of the Wilson Just Words reading method incorporated with the currently used Active Reading textbook would be used. Week 1: Only phonemic awareness and phonics instruction. A brief overview of written English, letter-sound keywords taught for consonants and short vowels, sound recognition for consonants and short vowels, phoneme segmentation for words with 3 sounds, blending sounds for decoding. Weeks 2-15 would be an incorporation of the Active Reading text and PA & P instruction for example: Week 4: Begin lesson with phonemic awareness instruction: Review of baseword + suffix, suffixes s, -es, -ing, -ed. Pronunciation of ed. Plurals. Homophones: to,two, too. 8 new sight words. Introduce text and new topic. Class discussion for background knowledge and

experiences with topic. Whole class discussion: scan text and identify new PA and P concepts and new sight words used in this weeks text (teacher will have previously previewed). Pre-teach new vocabulary. Skim text for general idea. Whole class discussion. Teacher read aloud to model prosody. Individual reading. Pair-work for comprehension exercise in textbook. Teacher circulates for individual fluency work, read aloud with students for practice. Weekly wrap-up to review concepts and dictation exercise for progress monitoring. Week 16: Review and final assessment. Conclusion The proposed course offers a balanced approach to reading instruction designed primarily for the ESL student with deficient alphabetic processing skills. The syllabus would address daily development of the five critical skills for reading. The ESL learner with word processing difficulties will benefit from explicit instruction of the alphabetic principle, syllabification and morphology. Applying these skills to text with a variety of topics and themes will allow the student the opportunity to reinforce concept knowledge. Improved decoding skills is necessary fluent reading. Students will apply their decoding skills to read words in isolation as well as words in phrases, sentences and in short passages and to practice prosody. High frequency sight words would be taught in pre-text exercises and would focus on their use in texts giving multiple exposures to practical usage. Vocabulary instruction would focus on high-frequency words first and follow with low-frequency (Nation, 2000,2005), and would provide multiple exposures in text and classroom practice. Students would be encouraged to build individual student vocabulary logs for reference. Comprehension is the ultimate goal of reading. With improved decoding skills, vocabulary development and ample prosody practice, students will develop

strategies to read sentences, and ultimately, entire texts in a meaningful manner. Daily and/or weekly dictation practice will monitor progress of concepts and sight word acquisition and can be used as an ongoing needs analysis. Given the phonological complexity of the English language, strong word analysis skills are critical for all ESL students and should be included in a balanced approach to ESL reading instruction.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- RubricsDocument3 pagesRubricsapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Project RationaleDocument6 pagesFinal Project Rationaleapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- My Teaching PhilosophyDocument2 pagesMy Teaching Philosophyapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final ProjectDocument3 pagesFinal Projectapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- Solo LessonDocument26 pagesSolo Lessonapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- Phonics and Adult English LearnersDocument20 pagesPhonics and Adult English Learnersapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- Appendices GB AdaptationDocument6 pagesAppendices GB Adaptationapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- Textbook Adaptation For Grammar and BeyondDocument5 pagesTextbook Adaptation For Grammar and Beyondapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- AppendicesDocument10 pagesAppendicesapi-219027126100% (1)

- GB 1Document12 pagesGB 1api-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Phonemic AwarenessDocument15 pagesReading Phonemic Awarenessapi-219027126Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- National Reading Panel Reading Reading Comprehension PhonicsDocument4 pagesNational Reading Panel Reading Reading Comprehension PhonicsmukarramuPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE ADocument31 pagesChapter 2 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE AAlexandra HiromiPas encore d'évaluation

- TESOL/ TEFL - A 120 Hour Certification Course We Are Proud Affiliate Partner ofDocument13 pagesTESOL/ TEFL - A 120 Hour Certification Course We Are Proud Affiliate Partner ofJeremiah DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- Phonological Phonemic-AwarenessDocument46 pagesPhonological Phonemic-AwarenessElena CalidroPas encore d'évaluation

- Form A Kindergarten Phonemic Awareness 2021Document6 pagesForm A Kindergarten Phonemic Awareness 2021ada.cojanPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 1 Week 1 PDFDocument108 pagesUnit 1 Week 1 PDFDušan Mićović100% (2)

- 4 - Component 2 Phonological AwarenessDocument54 pages4 - Component 2 Phonological AwarenessAlyssa Grace BrandesPas encore d'évaluation

- LBS 400-03 (WED) - Clements Syllabus - Spring 2021Document24 pagesLBS 400-03 (WED) - Clements Syllabus - Spring 2021Henry PapadinPas encore d'évaluation

- ALS - Raising Learner's Phonological Awareness As Foundational Skill To DecodingDocument35 pagesALS - Raising Learner's Phonological Awareness As Foundational Skill To DecodingValenzuela- Mrs. Analyn Roque100% (1)

- Phonemic AwarenessDocument16 pagesPhonemic AwarenessJoanne Ortigas100% (2)

- Remedial Instruction in ReadingDocument21 pagesRemedial Instruction in ReadingCruzille Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Presentation1 Kids 3-5 (Autosaved)Document43 pagesPresentation1 Kids 3-5 (Autosaved)ElvieEllazoPas encore d'évaluation

- DPE - Developmental Reading PDFDocument130 pagesDPE - Developmental Reading PDFJaenelyn AlquizarPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Students With High Incidence Disabilities Strategies For Diverse Classrooms 1st Edition Prater Test BankDocument14 pagesTeaching Students With High Incidence Disabilities Strategies For Diverse Classrooms 1st Edition Prater Test Bankdanielkellydegbwopcan100% (22)

- Phonemic Awareness InstructionDocument2 pagesPhonemic Awareness Instructioneva.bensonPas encore d'évaluation

- E-Portfolio For Teaching Internship by Angel BenibeDocument34 pagesE-Portfolio For Teaching Internship by Angel BenibeailaclavecillaPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Pillars For ReadingDocument20 pages5 Pillars For ReadingMarc Mijares BacalsoPas encore d'évaluation

- Phonemic Awareness PD - EaglesDocument6 pagesPhonemic Awareness PD - Eaglesapi-571885261Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Problem: Rationale and BackgroundDocument134 pagesThe Problem: Rationale and BackgroundSyrile MangudangPas encore d'évaluation

- Joann Phonemic Awareness Phonics FluencyDocument82 pagesJoann Phonemic Awareness Phonics FluencyEvelinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Phonemic Awareness Intervention Screening-Grades 2 or AboveDocument10 pagesPhonemic Awareness Intervention Screening-Grades 2 or Aboveapi-327232152Pas encore d'évaluation

- Science of Teaching Reading and WritingDocument159 pagesScience of Teaching Reading and WritingkaremPas encore d'évaluation

- Eng1 8-Week CurriculumDocument10 pagesEng1 8-Week CurriculumGizelle LaudPas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER II RRL Final DraftDocument13 pagesCHAPTER II RRL Final DraftLaila Boiser100% (2)

- Test of Phonemic-AwarenessDocument10 pagesTest of Phonemic-Awarenessapi-252238682Pas encore d'évaluation

- 10 10-10 14Document2 pages10 10-10 14api-260866611Pas encore d'évaluation

- Practice 1 Wonders 2020Document641 pagesPractice 1 Wonders 2020Mona ShehtaPas encore d'évaluation

- PhonemicDocument10 pagesPhonemicapi-345833578100% (1)

- Group 2 Final Na ThisDocument86 pagesGroup 2 Final Na Thisdegamoalthea019Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1.2 Phonological AwarenessDocument6 pages1.2 Phonological AwarenessMaria P12Pas encore d'évaluation