Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Application of Dialectical Behavior Therapy For Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder On Inpatient Units

Transféré par

Ismael RodriguezDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Application of Dialectical Behavior Therapy For Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder On Inpatient Units

Transféré par

Ismael RodriguezDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Psychiatric Quarterly, Vol. 72, No.

4, 2001

THE APPLICATION OF DIALECTICAL BEHAVIOR THERAPY FOR PATIENTS WITH BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER ON INPATIENT UNITS

Charles R. Swenson, M.D., Cynthia Sanderson, Ph.D., Rebecca A. Dulit, M.D., and Marsha M. Linehan, Ph.D.

Inpatient treatment of individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) is typically fraught with difculty and failure. Patients and staff often become entangled in intense negative therapeutic spirals that obliterate the potential for focused, realistic, and effective treatment interventions. We describe an inpatient treatment approach to BPD patients which is an application of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), a cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with BPD which has been shown to be effective in reducing suicidal behavior, hospitalization, and treatment dropout and improving interpersonal functioning and anger management. The inpatient DBT staff creates a validating treatment milieu and focuses on orienting and educating new patients and identifying and prioritizing their treatment targets. Inpatient DBT treatment

Charles R. Swenson, M.D., is Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, and Area Medical Director, Western Massachusetts Area, Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. Cynthia Sanderson, Ph.D., is Director of Training, Behavioral Technology Transfer Group. Rebecca A. Dulit, M.D., is Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, and Research Psychiatrist, Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute. Marsha M. Linehan, Ph.D., is Professor of Psychology, University of Washington, and Director, Behavioral Research and Therapy Clinics, University of Washington. Address correspondence to Charles Swenson, M.D., 695 Kennedy Rd., Leeds, MA 01053. e-mail: crobert01@aol.com. 307

0033-2720/01/1200-0307$19.50/0

C

2001 Human Sciences Press, Inc.

308

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

techniques include contingency management procedures, skills training and coaching, behavioral analysis, structured response protocols to suicidal and egregious behaviors on the unit, and consultation team meetings for DBT staff.

KEY WORDS: dialectical behavior therapy; borderline personality disorder; inpatient psychiatric treatment.

Hospital care of individuals meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD) is notoriously difcult for all involved parties. The inpatient staff, usually already stretched to its limits, faces life-threatening behaviors, impulsive episodes, and intense emotional lability of patients. The patients, already emotionally vulnerable and in crisis, face a myriad of restrictions and an overwrought, often invalidating environment. Outpatient resources for BPD patients are typically uncoordinated or insufcient which adds to the burden of the inpatient mission. Although BPD patients may appear similar to other mood-disordered patients on the unit, they often fail to respond to the usual helping strategies. When BPD patients continue to experience and communicate pain, the staff grows frustrated and angry. The resulting negative transactional spirals that often occur, with mutual blaming, punishment, and misunderstanding, can lead to some of the more painful scenarios of inpatient work (1,2). Over time the staff comes to anticipate resistance, manipulation, and hostile behavior from BPD patients (3), and BPD patients with multiple hospitalizations come to expect bias, mistrust, punishment, and rigidity from the staff (4). In this context, a successful and focused time-limited inpatient intervention is challenging. Psychoanalytic clinicians developed inpatient treatment models for BPD patients that emphasized milieu-based holding environments and psychodynamic therapy (510). Most such units have disappeared as lengths of stay have declined and reimbursers have withdrawn support. Another set of authors inuenced more by cognitive-behavioral and pragmatic outlooks have presented models for short term inpatient work with BPD patients which emphasize clear rules and punishment (limit-setting), contracting, early setting of discharge dates, and direct approaches to clearly specied target behaviors (1128). Three research studies have investigated inpatient adaptations of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), a manualized outpatient cognitivebehavioral therapy for BPD developed by Marsha Linehan (29). Barley et al (30) describe a homogeneous BPD unit with a several month

CHARLES R. SWENSON ET AL.

309

length-of-stay that adapted the following features of DBT: DBT orientation upon admission, DBT target priorities, individual therapy, group skills training, self-monitoring with diary cards, unit-wide incorporation of contingency management strategies, an emphasis on validation, and behavioral chain analysis. Average parasuicide rates were compared for three time periods: the 19 months on the unit prior to DBTs introduction, the 10 months during which DBT was being introduced, and the 14 months while DBT was in full operation. Parasuicide rates were signicantly lower during the third time period than during the other two, and similar rates did not change throughout the entire 43 months on a more traditional general psychiatric unit in the same hospital. In a second study, Springer et al (31) compared outcomes for patients on a brief stay unit (12.3 average days) between patients assigned to a Creative Coping (CC) group that incorporated DBT skills versus those assigned to a Wellness and Lifestyles Discussion group. Patients in each group attended approximately six sessions. Those from the CC group were more likely to believe that the skills would help them after discharge, but in fact they acted out on the unit more than the control group. In contrast to the recommendations of Linehans manual (29), patients in the CC group were encouraged to openly discuss their selfinjurious behaviors, which may well have created a contagion effect. In a third study, Bohus et al (32) reported pre-post data for a threemonth comprehensive inpatient DBT treatment provided prior to longterm outpatient therapy. The treatment incorporated behavioral analysis of the targeted behavior, orientation to the basics of BPD and DBT, skills training with a focus on skills to prevent future hospitalizations, and contingency management of reinforcers following self-injurious behaviors. The investigators compared the month prior to hospitalization and the month after and found signicantly fewer parasuicidal acts and signicant improvements in ratings of depression, dissociation, anxiety, and global stress. Many other inpatient programs throughout the U.S. and Europe are applying aspects of DBT in treating BPD and related populations. After a brief overview of DBT, this article will provide a rationale for and an overview of inpatient DBT and a detailed description of several of its most useful features. OVERVIEW OF DBT DBT is a cognitive-behavioral therapy for BPD (29,33). At its core, it balances a relentless insistence on problem solving, informed by behavioral

310

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

principles and techniques, with an attitude of acceptance embodied in validation, empathy, and a radical acceptance of things as they are in the moment. The treatment is based on a biosocial theory of the etiology and maintenance of BPD and posits that the central problem is emotional dysregulation. Emotional dysregulation is seen as having originated in and as being maintained by a lifelong mutually shaping transaction between a vulnerable temperament and an invalidating environment which leads to decient emotion modulation skills and motivational problems. The characteristic maladaptive behaviors of BPD (e.g., suicidal and impulsive behaviors) are viewed as direct sequelae of emotion dysregulation or as efforts to regulate painful and chaotic emotional states. Accordingly, in DBT, the therapist provides a validating environment, extinguishes maladaptive behaviors, teaches skills to help with emotions and relationships, and ensures that skills are reinforced, strengthened, and generalized to all relevant environments. All therapists of BPD patients are seen as requiring support that is partially provided for in a weekly DBT consultation team meeting (29). Controlled randomized research studies have shown that standard outpatient DBT reduces parasuicidal behaviors, length of hospitalizations, and treatment dropout (3435) and also improves anger regulation and interpersonal functioning (36). Replication studies are underway, and the model has been modied to treat the combination of substance abuse and BPD (37). In addition to inpatient applications, DBT has been adapted to day treatment, residential and forensic settings, case management, emergency services, family and adolescent treatment, and treatment of eating and dissociative disorders. Several large scale mental health systems in the United States, Canada and Europe have implemented DBT as a treatment for borderline patients across inpatient, outpatient, day treatment, residential, case management, and crisis services.

RATIONALE AND OVERVIEW OF INPATIENT DBT Certain typical features of inpatient treatment run counter to the optimal stance in DBT. The power differential between staff and patients, the common pejorative bias against borderline patients, the tendency for hospital staff to join together in managing the patient, and milieu reinforcement of compliant and passive behaviors run counter to DBTs collaborative therapy relationship, non-pejorative emphasis, preference for consulting to the patient regarding how to manage other professionals, and encouragement of active emotional expression and assertive

CHARLES R. SWENSON ET AL.

311

approaches. In addition, the frequent overload of emotional triggers on inpatient units can compromise the patients capacity to learn new behaviors and behavioral change which does occur on the inpatient unit must be generalized to natural outpatient contexts. Finally, hospitalization itself can reinforce maladaptive behavior and increase the likelihood of future suicidal and other maladaptive behaviors for many BPD individuals. Despite these challenges, DBT appears to be an excellent model with which to educate and orient newly admitted BPD patients and their families, to focus patients and staff on specic targets, to frame active and collaborative treatment relationships, and to teach and reinforce skills for getting out and staying out of hospitals. It can provide the model for either a DBT track on a heterogeneous acute unit or a BPD specialty unit with a more extended length of stay. The myriad of opportunities on inpatient units to coach skills and to monitor behavioral change is unmatched in outpatient life. Suicidal or egregious behaviors can be followed immediately by a structured response protocol that integrates contingency management, behavioral analysis, and skills training. The inpatient unit can provide the platform from which to consult to stalemates in outpatient treatment and, in selected cases, can provide a safe context in which to use exposure procedures to address and reduce unbearable emotions. Nursing staffs on inpatient DBT units have a pragmatic and systematic role that is a natural extension of nursing philosophy. STAGES AND TARGETS OF INPATIENT DBT Consistent with the DBT bias toward solving problems in the natural outpatient context, the highest mission of inpatient DBT is the elimination of future hospitalizations. For example, in the case of a newly admitted suicidal patient the DBT team specically targets those behaviors that prompted hospitalization rather than suicidal behaviors per se, so that the patient is more likely to remain out of the hospital during future suicidal episodes. The target categories for a short-term inpatient treatment are described. Dialectical synthesis is a pervasive target throughout treatment. One always looks for an opportunity to use DBTs Dialectical Strategies (29) to move the patient, the team, and the treatment from rigidity, polarity, and stasis towards exibility, synthesis, and change. Each patient begins the Pre-Treatment Stage, for which the targets are (1) Agreeing on goals and (2) Committing to the treatment plan. The initial assessment process culminates in a negotiation about

312

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

treatment targets (goals) and the therapist seeks a commitment from the patient to working on those targets. Many borderline patients enter the hospital involuntarily, and considerable work may be required to elicit a voluntary commitment to a set of goals. While some patients get stuck in pre-treatment, it is helpful for everyone involved to see that as the problem rather than acting as if some agreement is in place when it actually is not. The staff uses DBTs Commitment strategies (29) to elicit and strengthen each patients commitment. The Pre-Treatment Stage is an opportunity to meet patients at the door: welcome and orient them to the unit and DBT; validate their emotional pain and difculty; and structure preliminary problem solving, including a behavioral analysis of the behaviors prompting hospitalization and an introduction to crisis survival skills. In Stage 1, the treatment is guided by individualized target lists that were developed for each patient in the Pre-Treatment Stage, drawn from two overarching categories. The rst category is decreasing behaviors which prolong /prompt hospitalization and it has three subcategories. Suicidal, homicidal, and near lethal (e.g. severe anorexia) behaviors that prompted or prolong the hospital stay are the highest priority. The second subcategory is inpatient behaviors of staff and /or patient that destroy and therefore prolong inpatient treatment, and outpatient behaviors of therapist and /or patient that destroy outpatient treatment and prompt admission. Patient treatment-destroying behaviors include extreme examples of nonattending, noncollaboration, noncompliance, behaviors that burn out therapists, and destruction of other patients treatments. Therapist treatment-destroying behaviors include examples of serious imbalance (e.g., far too rigid or far too exible) as well as egregious (i.e., grossly disrespectful) behaviors. Depending on who is offering the treatment-destroying behaviors, the inpatient team might be consulting to the patient, to the outpatient therapist(s), or to their own inpatient staff. The third subcategory of targeted behaviors are egregious and parasuicidal inpatient behaviors and a specic technique has been developed for targeting these behaviorsthe Suicidal and Egregious Behaviors Protocolwhich will be discussed below. While working in Stage 1 to reduce behaviors that prompt or prolong hospitalization, the patient also works with the team to Increase Skills for Getting Out and Staying Out of the Hospital. These skills include (1) Crisis Survival Skills taught in DBTs Distress Tolerance Module, (2) Troubleshooting Skills to anticipate and address obstacles to a reasonable quality outpatient life, and (3) to the degree possible, DBT skills from other modules.

CHARLES R. SWENSON ET AL.

313

Once developed, each patients Target Priority List serves as a central organizing template in that individuals care. The head of the treatment team uses it as the patients treatment plan. Nurses, doctors, therapists, and other personnel use it as a guide to the most sensible content of meetings and sessions. The patient uses it to remain focused, to monitor progress, and to differentiate inpatient goals from longer-term outpatient goals. The target list is behaviorally specic, is constructed collaboratively by patient and therapist, lists targets in order of priority, and can be modied as time goes by. The main targets should be monitored on a diary card, a DBT rating form to be lled out daily or even more frequently, by the patient. The use of targets to organize the treatment and the specication of few enough focal targets to be of realistic use in a brief inpatient stay requires discipline and creativity. Not infrequently this will lead to a battle over the agenda of a given session, pitting the dened targets against other intense concerns of the moment. In DBT, this is considered to be a battle worth having, with some room for negotiation as long as the main target(s) is addressed. For example, a nurse in her daily check-in with a patient might insist that they address the patients suicide threat of that morning, but the patient would prefer to talk about another topic. The nurse can offer that some work on the suicide threat could be followed by the patients preferred topic, thereby trying to reinforce target-focused work. The overall impact of sticking to the target priorities, over and over again, is somewhat aversive for the patient and staff but facilitates a concise and effective hospitalization.

CONTINGENCY MANAGEMENT If applied thoughtfully and consistently, the use of contingency management in the inpatient setting can be powerfully effective in moving patients toward their targets and in maintaining the necessary limits of the unit. Contingency management is the therapeutic manipulation of behavioral consequences to increase certain behaviors and to decrease others. The most relevant contingency management principles include positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, random intermittent reinforcement, extinction, punishment, and shaping. The staff has endless opportunities every day to reinforce small skillful steps in targeted directions with positive reinforcement, to extinguish dysfunctional behaviors by withholding reinforcement and soothing the patient, and to punish disturbing dysfunctional behaviors if

314

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

absolutely necessary. Immediate reinforcement is preferred over delayed reinforcement, natural contingencies are preferred over articial ones, and extinction is preferred over punishment. Because of the necessity of providing a controlled, safe environment for a large number of highly distressed individuals, punishment (not punitiveness) plays a larger role in inpatient treatment than it ordinarily does in outpatient treatment. One wants an atmosphere permeated by positive reinforcement for small gains while punishment is used effectively and as sparingly as possible. Unfortunately, many inpatient units routinely and inadvertently reinforce the very behaviors targeted for reduction and extinguish and punish those behaviors targeted for increase. For instance, the typical inpatient responsiveness to the patient who has injured herself can reinforce such behaviors throughout the unit, and the relative lack of responsiveness to quiet coping and adaptive communication can extinguish such efforts. The DBT staff regularly asks: what is the function of this (maladaptive) behavior? what particular stimuli set off the chain of events that led to this behavior?, and what internal and external consequences reinforced it? Further, what might we be doing that inadvertently reinforces (strengthens) this behavior? how might we extinguish this behavior and simultaneously reinforce more adaptive alternatives?, and at what point will we need to institute punishment in order to reduce this particular behavior? Of some comfort is the fact that if the staff maintains a consistent focus on the patients targeted behaviors, cares about the patient, and remains awake to what is occurring, they will automatically use most principles of learning effectively. Nevertheless, staff training in behavioral principles is critical (3839). Consider an example in which a patient was cutting herself daily, sometimes deeply, with any sharp instrument within reach. In each episode, the cutting led to a urry of activity by staff and fellow patients to calm her. Occasionally, she was even wrestled into restraints. She was placed on maximal observation status which required her to be accompanied 24 hours per day by a staff member and her doctor to meet with her in the security room. A behavioral analysis done with the patient during a calm interlude shed little light on the original triggers for the cutting, but did show that certain features of the units response were reinforcing the cutting. The time with staff was soothing, the doctor visits in the security room felt special, the episodes of restraints brought longed-for physical contact, and the disruption of the unit gave the patient a sense of control over a frightening and intimidating environment.

CHARLES R. SWENSON ET AL.

315

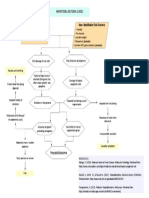

The DBT team decided to remove the likely reinforcers for her selfinjurious behavior. Self-cutting was no longer to be followed by soothing contacts and doctor visits to the security room. The staff members sitting with the patient on maximal observation status were instructed to behave more austerely. The patient was given a worksheet that guided her through a written behavioral analysis of the episode. She was expected to attempt to repair any interpersonal damage she had done and was immediately reinforced for doing so. And, most importantly, the patient was immediately and emphatically offered attention for any constructive efforts to communicate distress. When the staff had effectively removed the reinforcers for the target-relevant behavior, the patient initially intensied her cutting in frequency and severity. This initial increase is a behavioral burst or extinction burst and must be anticipated and temporarily endured before the behavior actually declines. The Inpatient Protocols for Suicidal and Egregious Behavior, discussed below, create a routine management structure that systematically accomplishes all of the above. Protocols for Suicidal and Egregious Behavior Several inpatient units applying DBT have implemented protocols that dene a consistent response to self-destructive and egregious behaviors. Egregious behaviors include universal ones, i.e. those that would be outrageous and disruptive on any inpatient unit (e.g., violence), and context-specic ones, i.e. those that are particularly outrageous or disruptive given the task and or limits of a particular unit (e.g., hoarding food in a closet on an eating disorders unit). These protocols combine contingency management, behavioral analysis, and skills training and include the following steps: Immediately following a self-destructive or egregious episode, the charge nurse makes the decision as to whether a protocol is to be implemented. If so, someone on the staff orients the patient to the protocol and gives him/her a written introduction and worksheet. The complete protocol then consists of three parts: (1) behavioral analysis, (2) presentation of the analysis to peers, and (3) repair. In Step 1, the patient works alone on a behavioral analysis of the episode, guided by the worksheet. In a brief meeting, a nurse reviews and comments on the analysis, reinforcing good work, highlighting patterns and suggesting additions. If the patient is cognitively disturbed or limited, staff help or tutoring with Step 1 may be necessary. In Step 2, the patient meets with the other DBT patients, with or without staff members, to present his/her behavioral analysis and receive feedback.

316

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

This Protocol Meeting can benet everyone; the peers are coached and encouraged to use effective interpersonal and distress tolerance skills while giving feedback. At the end of Step 2, the patient again meets with a nurse for feedback and to prepare for Step 3. In Step 3, the patient tries to repair any damage done by the behavior; this usually involves meeting with individuals who were especially impacted by the behavior in question. While on the protocol, the patient does not attend any other treatment meetings since protocol work is considered the highest priority in his/her treatment at that point in time. The experience with these protocols when they are truly adopted, adapted, and sanctioned by unit leadership has been uniformly excellent both as learning tools and in reducing the number and the disruptiveness of the targeted episodes. As disturbing as suicidal and egregious behaviors continues to be on inpatient units, the behaviors become less disruptive when such a protocol denes a consistent response. Program Within a Program DBT recommends the use of a DBT program within a program as a structure that reinforces the Pre-Treatment patient to choose to commit to working in treatment. The essence of this strategy is that the consequences of committing to the DBT program are reinforcers for most individuals: enriched treatment opportunities including more time with the staff. The noncommitting patient is offered a less enriched program that focuses specically on committing to a DBT treatment plan. For instance, one unit offered a Commitment group for Pre-Treatment patients and offered individual and group therapy only to those who commit to Stage 1. Observing Limits In each case, in each setting, and at each point in time, DBT therapists and staff are responsible to observe their own personal limits, i.e., the limits within which they can effectively do their jobs. This process requires that the staff members each attend to their own personal limits and courageously and tactfully share them with patients. Observing limits effectively helps to prevent staff burnout. Observing limits differs from setting limits which involves unit-wide imposition of pre-determined and uniform limits upon patients. By observing limits, the staff individualizes care, conveys respect, and models effective self care to patients who have often had their own limits violated. Persistent violations of stated limits become targeted behaviors, subject to

CHARLES R. SWENSON ET AL.

317

behavioral analyses and contingency management. The therapist reinforces respect for limits and responds aversively to violations. For example, one staff member may be comfortable with profanities while another is not; they will observe different limits in that area. One staff member may not mind if a given patient accompanies her on hall rounds; another staff member may prefer to go about that task alone. One staff member may be feeling frustrated with and therefore need a bit of distance from a patient with whom another staff member is perfectly comfortable. Within DBT, these differences are seen as natural, but staff member trained in models which emphasize limit-setting and boundaries may feel frightened at rst by the idea of units tolerating natural differences among staff, fearing that things will get out of control and that patients will split staff. In addition to observing ones own personal limits, each staff member observes the programmatic limits, which are determined and articulated by the program director as those limits needed for effective programmatic functioning. The programmatic limits circumscribe all staff members personal limits. For instance, at a time of stafng shortages, the unit director may articulate a programmatic limit around the amount of time that nurses may spend in one-on-one meetings with patients. The staff observes the programmatic limit with patients, clarifying that it is needed for the unit staff and may very well be undesirable for many patients. The patient might be unhappy with the limit, but is not being blamed for neediness or for consuming the staff. Persistent non-compliance with programmatic limits is addressed in appropriate meetings, consultation team with staff members, and therapy and other DBT meetings with patients.

SUPPORT FOR THE STAFF Repeated painful clinical encounters with borderline patients have left many inpatient staff feeling helpless and frustrated. Unfortunately, patients sometimes receive blame for staff not having yet learned to effectively understand and treat them. To help staff members avoid burnout, maintain an objective and compassionate stance, and offer consistent DBT, the DBT staff members constitute a consultation team with a weekly meeting. The team helps each member remain within the frame of DBT, learn the treatment increasingly thoroughly, and maintain morale. This often takes the form of working together to understand the function of a given patients ongoing maladaptive behaviors rather than to blame the patient for them, to support each staff

318

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

member in dening and observing his/her personal limits, or to validate and cheerlead a beleaguered team member. While many of the same staff members will take part in the usual inpatient interdisciplinary team meetings or rounds, the DBT consultation team exists separate from these in order to allow a complete focus on doing DBT according to its principles and guidelines. It is of course not necessary that all staff members on the unit are doing DBT. The DBT staff on a heterogeneous acute unit accepts that other staff members are not doing DBT. DBT patients must be oriented to this fact as well. The consultation team sometimes helps a frustrated team member regain a non-pejorative stance. For instance, one such team member was describing how a certain patient was sabotaging his discharge plans by refusing to attend relevant interviews. The team leader validated the staff members frustration and then wondered aloud whether the team could come up with a more objective and less pejorative interpretation of the patients behavior that was still true to the observations. Another team member commented, It could be that he is terried of leaving, that he is avoiding the steps in the discharge process, and that we need to validate his feelings right now without backing off from discharge planning. An effective consultation team meeting will often help a team member toward dialectical balancebetween using validation and problem-solving, between staying involved with a patient while observing personal limits, and between keeping inpatient goals realistic while being fully aware of the enormous problems of a patients life. SPLITTING IN HOSPITAL TREATMENT Inpatient staff members repeatedly get into intense disagreements about borderline patients. Psychodynamic theorists have often explained this as the activation, in the social eld surrounding the patient, of her split internal world. The patient treats one staff member as the good object and another as the bad object or activates a fault line that already existed among the inpatient staff. The actual disagreement is considered to be an externalization of the patients internal conict, and to bring her a sense of control and relief. The most therapeutic responses, given this conceptualization, are to contain and to study the disagreement which can then shed light on the nature of the patients internal conicts, to shore up the relationship between the two staff members or subgroups who then see the part they have been playing in the patients psychological world, and to offer the patient

CHARLES R. SWENSON ET AL.

319

a corresponding interpretation of her behaviors. Unless done with extraordinary skill, the patient typically feels blamed for the conict between the staff members. The DBT approach to these situations follows from DBTs Dialectical, Consistency, and Consultation-to-the Patient Agreements (29). If two staff members disagree about a particular patient, the team looks for the validity in each point of view and seeks to come up with an overarching understanding that synthesizes the two. It is not assumed that the patient in question is (consciously or unconsciously) trying to split the staff, and the goal is not to formulate an interpretation to the patient. It is done to nd a synthesis within the team that is sufciently complex and accurate. These disagreements are thought to be natural and expectable in working with patients who are communicating pain and who are not responding promptly to help. No effort is made to get staff members to hold the same point of view or to interact with the patient in the same way. DBT emphasizes that individuals in life are typically inconsistent with one another and that the inpatient setting is more similar to real life if natural differences among staff are expressed. A patient complaining to one staff member about another is considered quite natural and is an opportunity for that staff member to consult to the patient about how to handle the situation. The DBT staff member is inclined against intervening in the environment, including with other staff members, in order to resolve difculties for the patient. For instance, the patient may say to Nurse A: I cant stand Nurse B, she really has it in for me. She avoids me when I want to talk to her, and she is available for everyone else. Nurse A might say: Well, if you want more help from Nurse B, lets talk about how to get it. Its a chance to get better at getting what you need from other people and maybe it will help you in certain relationships outside the hospital. Nurse A would generally not approach Nurse B about the matter. SKILLS TRAINING The inpatient DBT program is an ideal setting for the acquisition and strengthening of DBT skills (33), most importantly the Distress Tolerance Skills that may facilitate staying out of the hospital. Skills can be taught in regularly scheduled groups, practiced and strengthened every day, generalized in the milieu and in the patients natural environment during passes. After discharge, follow-up is crucial to help in generalizing skills to relevant outpatient contexts. Toward that end, some inpatient units in settings that lack outpatient DBT skills groups have arranged follow-up groups.

320

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

In addition to teaching and reinforcing the particular skills, the program cultivates a skills culture that has certain benets. The focus is on pragmatism, concrete steps, here-and-now capabilities. This workshop atmosphere not only provides a constructive focus on change; it also implicitly counters a pejorative focus on bad behavior and deep pathology that resonates with patients hopelessness about being fundamentally awed, evil, or crazy. The atmosphere helps to reduce shame and to empower the patient with validation, respect, and practical tools. Bringing together the borderline (and related) patients for skills training groups has the additional benecial effect of providing a group of peers for each patient, peers that may have similar behaviors and issues and who are taking concrete steps together. The group participation is supportive. Mutual criticism and processing of group issues are prohibited. It is a class in which the leader explicitly states that each group member is there to help him or her self and to support each other in learning skills. Most units have found that these groups have raised morale of patients and staff members. The 24 hour-a-day, 7-day-a-week nature of inpatient work allows for creative ways to implement skills groups. They can meet several times per week, including on weekends and evenings. Patients can be combined into larger groups for teaching new skills. Groups to review homework will function best with six or fewer patients per group so each patient can receive at least ten minutes of individual attention. Extra groups can be added for review, for inpatient-related special topics (e.g., how to use interpersonal skills in other therapeutic groups on the unit, how to give difcult feedback non-judgmentally, etc.), or for emphasizing the application of the skills outside the hospital. One unit ran a consultation group, a voluntary meeting in which patients could present any problematic situation and get help in thinking which skills might help them. The teaching of mindfulness skills, which involve steps toward balance and centeredness, can be taken out of the usual skills curriculum and built into the units daily structure, with Mindfulness in the Morning or Mindfulness at Mealtime. Creative homework assignments that involve practicing skills with the staff or peers, in the milieu and on passes, can be lively additions to the usual assignments drawn from the DBT Skills Manual. As has been noted, the acute unit will teach a subset of the overall skills especially likely to reduce future hospitalizations. Five, eight, and ten session applications have been developed (28,31), typically highlighting Distress Tolerance Skills and touching on Mindfulness and Interpersonal Effectiveness as well. The skills, once chosen, will be taught

CHARLES R. SWENSON ET AL.

321

over and over again in a cyclical fashion. A new patient can receive an orientation to the skills and to skills training, in person or on video, and then enter the group at whatever point in the cycle the group happens to be. Repetition is important in skills training and patients who stay beyond the length of the group can go over the skills again. The nursing staff who is familiar with the specic skills can coach patients to use them in the milieu at appropriate moments. This strengthens skills acquisition and begins the process of generalization. For instance, the patient with panic, fear, anger, and parasuicidal urges can be coached to use crisis survival skills, such as distracting or self-soothing, and can be positively reinforced for trying. The patient who wont talk with family members to whom she will be returning upon discharge can be coached to use practical guidelines for interpersonal effectiveness and do a role-play rehearsal with staff members. The patient who regularly dissociates prior to self-injury can be taught to use mindfulness skills to increase voluntary attentional control at critical predissociation moments. Some units have found it helpful to rotate various staff members into skills group teaching positions over time as a way to increase the skills-potency of the overall milieu. PRIMARY THERAPY As is the case for the DBT outpatient, the DBT inpatient needs a primary therapist to be the quarterback of the patients overall treatment and treatment team. The primary therapist assesses and orients the patient, determines the target list and works toward a commitment, monitors overall progress and coordinates efforts of other DBT team members. He or she conducts behavioral analyses of target behaviors in sessions, weaves in skills and works toward practical problem solving realistic to a brief inpatient stay. Establishing an optimal balance between validating the patient while insisting on behavioral change is difcult in a brief stay precipitated by crisis behaviors, but the primary therapist needs to set the tone in this respect for the overall team. Driven by economic considerations, some DBT units have delivered the primary therapy functions and strategies in group therapy formats. This has the advantage of harnessing peer reinforcement toward change as well as capitalizing on the commonalities among patients. In addition, the elimination of individual therapy on the inpatient unit, reserving it for outpatients, may help to reduce some reinforcement for staying in the hospital. On one unit, patients were seen individually by a therapist for assessment, orientation, targeting and commitment and then join others in that therapists DBT group therapy. The group

322

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

met two times per week for 1 1/2 hours, working sequentially on each patients target behaviors which are visible to the group on a ip chart. Each patients diary card is reviewed and behavioral analyses are done with interaction usually between the therapist and the patient who is the focus of the moment. The nal half hour of each group is devoted to group relationship building and discharge planning. THE RELATIONSHIP WITH THE OUTPATIENT THERAPIST The relationship between inpatients and their outpatient therapist will vary. In an ongoing outpatient therapy in which inpatient visits might reinforce being in the hospital, the DBT therapeutic position is to let the patient go at the door and to pine for her return to outpatient therapy. If the outpatient therapy is new or if there is not sufcient attachment, the outpatient therapist might strategically plan visits or other contact with the inpatient to elicit a stronger attachment. Choices about contact should be made in a collaborative spirit by the patient, the outpatient therapist, and the inpatient staff. SUMMARY Highlights of the inpatient application of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Borderline Personality Disorder have been presented. Patients with non-BPD diagnoses may benet from this approach, especially those who use maladaptive behaviors to cope with painful and poorly regulated emotions. While skills training and generalization into the milieu are the most natural and most common inpatient DBT applications and can by themselves result in substantial benets, the use of other structures and strategies of DBT can further strengthen and focus the treatment. These include the use of target priorities, contingency management strategies, biosocial theory, consultation teams, and the functions of the primary therapist. The inpatient unit can play a limited, focused, and powerful role in the overall treatment of the patient with BPD, especially if it is part of a larger, vertically integrated system. REFERENCES

1. Main TF: The ailment. British Journal of Medical Psychology 30:l29145, 1957. 2. Gabbard G: The treatment of the special patient in a psychoanalytic hospital. International Review of Psychoanalysis 13:333347, 1986.

CHARLES R. SWENSON ET AL.

323

3. Gallop R, Lancee W, Garnkel P: How nursing staff responds to the label borderline personality disorder. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:815819, 1989. 4. Sadovoy J, Silver D, Book HE: Negative responses of the borderline to inpatient treatment. American Journal of Psychotherapy 33:404417, 1979. 5. Adler G: Hospital treatment of borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 130:3236, 1973. 6. Gunderson J: Borderline Personality Disorder. Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Press, Inc., 1984. 7. Kernberg OF: Severe Personality Disorders: Psychotherapeutic Strategies. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1984. 8. Masterson J, Costello J: From Borderline Adolescent to Functioning Adult. New York, Brunner/ Mazel, 1980. 9. Swenson C: Modication of destructiveness in the long-term inpatient treatment of severe personality disorders. International Journal of Therapeutic Communities 7:153163, 1986. 10. Levine I, Wilson A: Dynamic interpersonal processes and the inpatient holding environment. Psychiatry 48:341357, 1985. 11. Swenson C: Supportive elements of inpatient treatment with borderline patients, in Supportive Therapy for Borderline Patients. Edited by Rockland L. New York, Guilford Press, 1992. 12. Miller L: The formal treatment contract in the inpatient management of borderline personality disorder. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:985987, 1990. 13. Bloom B, Rosenbluth M: The use of contracts in the inpatient treatment of the borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Quarterly 60:317327, 1989. 14. McKeegan G, Geczy B, Donat D: Applying behavioral methods in the inpatient setting: Patients with mixed borderline and dependent traits. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:5564, 1993. 15. Gallop R: Self-destructive and impulsive behavior in the patient with borderline personality disorder: Rethinking hospital treatment and management. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 6:178182, 1992. 16. Sansone R, Madakasira S: Borderline personality disorder: Guidelines for evaluation and brief inpatient management. The Psychiatric Hospital 21:6569, 1990. 17. Wishnie HA: Inpatient therapy with borderline patients, in Borderline States in Psychiatry. Edited by Mack, IF. New York, Grune and Stratton, 1975. 18. Viner J: Milieu concepts for short term hospital treatment of borderline patients. Psychiatric Quarterly 57:127133, 1985. 19. Nurnberg HG, Suh R: Time-limited treatment of hospitalized borderline patients: Considerations. Comprehensive Psychiatry 19:41943 1, 1978. 20. Friedman H: Some problems of inpatient management of borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 126:299304, 1969. 21. Nehls N: Brief hospital treatment plans for persons with borderline personality disorder: Perspectives of inpatient psychiatric nurses and community mental health clinicians. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 8:303311, 1994. 22. Miller L: Inpatient management of borderline personality disorder: A review and update. Journal of Personality Disorder 3:122134, 1989. 23. Beard H, Marlowe M, Ryle A: The management and treatment of personality disordered patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:541545, 1990. 24. Davis MH, Casey DA: Utilizing cognitive therapy on the short-term psychiatric inpatient unit. General Hospital Psychiatry 12:170176, 1990.

324

PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY

25. Rosenbluth M, Silver D: The inpatient treatment of borderline personality disorder, in Handbook of Borderline Disorders. Edited by Silver D, and Rosenbluth M. Madison, Connecticut, International Universities Press, 1992. 26. Sederer L, Thorbeck J: First do no harm: Short term inpatient psychotherapy of the borderline patient. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:692697, 1986. 27. Silver D, Rosenbluth M: Inpatient treatment of borderline personality disorder, in Borderline Personality Disorder: Etiology and Treatment. Edited by Paris J., Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Press, 1993. 28. Miller CR, Eisner W, Allport C: Creative coping: A cognitive-behavioral group for borderline personality disorder. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 8:280285, 1994. 29. Linehan ML: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993. 30. Barley W, Buie S, Peterson E, et al: Development of an inpatient cognitive-behavioral treatment program for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders 7:232240, 1993. 31. Springer T, Lohr NE, Buchtel HA, Silk KR: A preliminary report of short-term cognitive-behavioral group therapy for inpatients with personality disorders. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 5:5771, 1996. 32. Bohus M, Haaf B, Stiglmayr C, Pohl U, Bohme R, Linehan M: Evaluation of inpatient dialectical-behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. A prospective study. Behavior Research and Therapy 38:875879, 2000. 33. Linehan, MM: Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993. 34. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:10601064, 1991. 35. Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE: Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:971974, 1993. 36. Linehan MM, Tutek DA, Heard HL, et al: Interpersonal outcome of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:17711776, 1994. 37. Linehan MM, Dimeff LA: Extension of Standard Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) to Treatment of Substance Abusers with Borderline Personality Disorder (DBT-S): Treatment Procedures Manual. Department of Psychology, University of Washington, 1996. 38. Donat D, McKeegan G: Behavioral knowledge among direct care staff in an inpatient psychiatric setting. Behavioral Residential Treatment 5:95103, 1990. 39. Donat D, McKeegan G, Neal B: Training inpatient psychiatric staff in the use of behavioral methods: A program to enhance utilization. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 15:6974, 1991.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Proposed Treatment Connection for Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and Traumatic Incident Reduction (TIR)D'EverandA Proposed Treatment Connection for Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and Traumatic Incident Reduction (TIR)Évaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- DBT For Bipolar DisorderDocument26 pagesDBT For Bipolar DisorderWasim RashidPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence-Based Treatments For Borderline Personality Disorder Implementation, Integration, and Stepped Care.Document15 pagesEvidence-Based Treatments For Borderline Personality Disorder Implementation, Integration, and Stepped Care.drguillermomedinaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Case Study About Severe Borderline Personality Disorder.: August 2020Document12 pagesA Case Study About Severe Borderline Personality Disorder.: August 2020Aimen MurtazaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grief Sentence Completion PDFDocument1 pageGrief Sentence Completion PDFÁdám KószóPas encore d'évaluation

- Borderline Personality Disorder: Presented By: Nurul Syazwani Binti Ramli 080100315 K5Document11 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder: Presented By: Nurul Syazwani Binti Ramli 080100315 K5Nurul Syazwani Ramli100% (1)

- Cause and Effect of Broken RelationshipDocument18 pagesCause and Effect of Broken Relationshipshafi0% (1)

- Treatment For BPDDocument25 pagesTreatment For BPDLuci BaldwinPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical InterviewDocument7 pagesClinical InterviewHannah FengPas encore d'évaluation

- Bipolar Disorder and PTSD Case StudyDocument4 pagesBipolar Disorder and PTSD Case Studyapi-302210936Pas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Borderline Personality Disorder?Document8 pagesWhat Is Borderline Personality Disorder?aagPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy For Substance AbuseDocument15 pagesCognitive Behavior Therapy For Substance AbusePutri Zatalini Sabila100% (1)

- ManningHealing Hearts Conference 11.10.12-1 PDFDocument42 pagesManningHealing Hearts Conference 11.10.12-1 PDFSvetlana RadovanovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Etiology: Borderline Personality DisorderDocument3 pagesEtiology: Borderline Personality DisorderJordz PlaciPas encore d'évaluation

- Borderline Personality Disorder Implications in Family and Pediatric Practice 2161 0487.1000122 PDFDocument6 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder Implications in Family and Pediatric Practice 2161 0487.1000122 PDFFarida Durotul100% (1)

- Mastering ChainDocument15 pagesMastering ChainMarianela Rossi100% (1)

- Neurocognitive DisordersDocument26 pagesNeurocognitive Disordershaidar aliPas encore d'évaluation

- Diagnosing Borderline Personality DisorderDocument12 pagesDiagnosing Borderline Personality DisorderAnonymous 0uCHZz72vwPas encore d'évaluation

- Borderline Personality BPD FactsheetDocument20 pagesBorderline Personality BPD Factsheetheeseunger lolPas encore d'évaluation

- Suicide Risk Assessment Guide NSWDocument1 pageSuicide Risk Assessment Guide NSWapi-254209971Pas encore d'évaluation

- 3b. Borderline Personality Disorder 2021Document14 pages3b. Borderline Personality Disorder 2021spartanPas encore d'évaluation

- Personality DisordersDocument63 pagesPersonality DisordersEcel AggasidPas encore d'évaluation

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)Document30 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder (BPD)Bude Viorel100% (1)

- Deficits of Cognitive Restructuring in Major Depressive DisorderDocument6 pagesDeficits of Cognitive Restructuring in Major Depressive DisorderIntan YuliPas encore d'évaluation

- The Art of AssessmentDocument12 pagesThe Art of AssessmentTee SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Trauma FocusedCognitive BehavioralTherapy (TF CBT)Document2 pagesTrauma FocusedCognitive BehavioralTherapy (TF CBT)Joel RamosPas encore d'évaluation

- Substance Abuse - Stages of ChangeDocument37 pagesSubstance Abuse - Stages of ChangeAbdul Halim Ab Hamid100% (1)

- Distinguishing Bipolar From BorderlineDocument10 pagesDistinguishing Bipolar From BorderlineTímea OrszághPas encore d'évaluation

- Metacognitive Training BPDDocument90 pagesMetacognitive Training BPDpsicbeaPas encore d'évaluation

- DBT For Borderline Personality DisorderDocument17 pagesDBT For Borderline Personality Disorderapi-595939801Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Intersectionality of Bipolar Disorder With Borderline Personality DisorderDocument14 pagesThe Intersectionality of Bipolar Disorder With Borderline Personality DisorderMuskaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Linking Assessment and TreatmentDocument37 pagesLinking Assessment and Treatmentaimee2oo8Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wellways Fact Sheet BPDDocument4 pagesWellways Fact Sheet BPDJonty ArputhemPas encore d'évaluation

- CBTDocument2 pagesCBTStudentPas encore d'évaluation

- Treatment Plan Sample PDFDocument4 pagesTreatment Plan Sample PDFRM April AlonPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychotherapy of Personality DisordersDocument6 pagesPsychotherapy of Personality DisordersÁngela María Páez BuitragoPas encore d'évaluation

- Borderline Personality Disorder Implications in Family and Pediatric Practice 2161 0487.1000122Document6 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder Implications in Family and Pediatric Practice 2161 0487.1000122Farida DurotulPas encore d'évaluation

- DBT From BeyondDocument7 pagesDBT From BeyondFlorencia PollakPas encore d'évaluation

- Brochure Are Your Emotions Too Difficult To HandleDocument2 pagesBrochure Are Your Emotions Too Difficult To HandleAguz PramanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Behavioral Activation As An Intervention For Coexistent Depressive and Anxiety SymptomsDocument13 pagesBehavioral Activation As An Intervention For Coexistent Depressive and Anxiety SymptomsAndreea NicolaePas encore d'évaluation

- DBT Diary Card - BackDocument2 pagesDBT Diary Card - BackCiupi Tik100% (1)

- Overcoming Borderline Personality Disorder: A Family Guide For Healing and Change - Valerie M.A. PorrDocument5 pagesOvercoming Borderline Personality Disorder: A Family Guide For Healing and Change - Valerie M.A. PorrgilikixyPas encore d'évaluation

- Treatment of Borderline Personalilty DisorderDocument10 pagesTreatment of Borderline Personalilty DisorderyowwwPas encore d'évaluation

- FC Child-Adolescent Intake Forms Fisa AdolescentDocument4 pagesFC Child-Adolescent Intake Forms Fisa Adolescentnicoletagr2744Pas encore d'évaluation

- List of TestsDocument12 pagesList of TestsJane MonteroPas encore d'évaluation

- Borderline Personality Disorder: Still A Diagnosis of Exclusion?Document6 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder: Still A Diagnosis of Exclusion?Chris RavenPas encore d'évaluation

- BPD, DiagnosisDocument5 pagesBPD, DiagnosisMArkoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions For PTSDDocument20 pagesCognitive-Behavioral Interventions For PTSDBusyMindsPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychotherapy For Specific Phobia in Adults PDFDocument6 pagesPsychotherapy For Specific Phobia in Adults PDFdreamingPas encore d'évaluation

- Interviewing Borderline Personality DisorderDocument3 pagesInterviewing Borderline Personality DisorderbabarsagguPas encore d'évaluation

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder 0Document10 pagesObsessive-Compulsive Disorder 0Faris Aziz PridiantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Strategies of CBTDocument13 pagesBasic Strategies of CBTCristian Asto100% (1)

- Attachment and Borderline Personality DisorderDocument18 pagesAttachment and Borderline Personality Disorderracm89Pas encore d'évaluation

- Best Practice Workbook - Bipolar Disorder-Yong Xiang YiDocument45 pagesBest Practice Workbook - Bipolar Disorder-Yong Xiang YiJuraidahMohdNoohPas encore d'évaluation

- Caz 4Document17 pagesCaz 4Marinela MeliszekPas encore d'évaluation

- Borderline Personality Disorder - 0Document8 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder - 0Vanshla GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Group Therapy in Psychotic InpatientsDocument9 pagesGroup Therapy in Psychotic InpatientsLeo GondayaoPas encore d'évaluation

- W3 05 Ahu KocakDocument24 pagesW3 05 Ahu KocakClaudiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Disorder of Personality and BehaviorDocument51 pagesDisorder of Personality and BehaviorTriee Ayiie Minniy100% (1)

- Borderline Personality Disorder - Wikipedia The Free Encyclope PDFDocument34 pagesBorderline Personality Disorder - Wikipedia The Free Encyclope PDFstephPas encore d'évaluation

- Zniber Group Counseling GuideDocument45 pagesZniber Group Counseling GuideIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Bases de Los Desvíos D AtenciónDocument5 pagesBases de Los Desvíos D AtenciónIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Zniber Group Counseling GuideDocument45 pagesZniber Group Counseling GuideIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- What The Best Therapists Are Like As PeopleDocument6 pagesWhat The Best Therapists Are Like As PeopleIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive Narrative PsychotherapyDocument13 pagesCognitive Narrative PsychotherapyЈован Д. РадовановићPas encore d'évaluation

- Using Art in Narrative Therpay - Enhancing Therpeutic PossibilitiesDocument13 pagesUsing Art in Narrative Therpay - Enhancing Therpeutic PossibilitiesIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Cognitive Behavioral Guided Self Help For The Treatment Od Recurrent Binge EatingDocument19 pagesCognitive Behavioral Guided Self Help For The Treatment Od Recurrent Binge EatingIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- This Si Your Brain On MindfulnessDocument7 pagesThis Si Your Brain On MindfulnessIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Brain and EmotionsDocument380 pagesThe Brain and EmotionsIsmael Rodriguez100% (3)

- Strategies To Improve Patients Adherence To MedicationDocument7 pagesStrategies To Improve Patients Adherence To MedicationIsmael Rodriguez100% (1)

- Obesity GuideDocument94 pagesObesity GuideAbhishek RaghuvanshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Attempting To Lose Weight Specific Practices Among Us AdultsDocument5 pagesAttempting To Lose Weight Specific Practices Among Us AdultsIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- The Neurocognitive Connection Between Physical Activity and Eating BehaviourDocument13 pagesThe Neurocognitive Connection Between Physical Activity and Eating BehaviourIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- REBT Education KnausDocument146 pagesREBT Education KnausmarineanuPas encore d'évaluation

- CON 5asDocument50 pagesCON 5asIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- TRRP Treatment Adherence and Weight LossDocument12 pagesTRRP Treatment Adherence and Weight LossIsmael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategies That Promote Behavior Change and Health Weight Management+Document21 pagesStrategies That Promote Behavior Change and Health Weight Management+Ismael RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Herbs or Natural Products CancerDocument16 pagesHerbs or Natural Products CancerANGELO NHAR100% (1)

- Lista OndamedDocument2 pagesLista Ondamedmona miaPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomic and Visual Function Outcomes in Paediatric Idiopathic Intracranial HypertensionDocument6 pagesAnatomic and Visual Function Outcomes in Paediatric Idiopathic Intracranial HypertensionRani PittaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 6 - AnxietyDocument32 pagesLecture 6 - AnxietyPatrick McClairPas encore d'évaluation

- Non-Modifiable Risk Factors: Hepatoblastoma CaseDocument1 pageNon-Modifiable Risk Factors: Hepatoblastoma CaseALYSSA AGATHA FELIZARDOPas encore d'évaluation

- Choque Séptico en Anestesia.: Yamit Mora Eraso. Residente 1 Año AnestesiologiaDocument68 pagesChoque Séptico en Anestesia.: Yamit Mora Eraso. Residente 1 Año AnestesiologiaAlex MoraPas encore d'évaluation

- BVCCT-501 Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory BasicsDocument52 pagesBVCCT-501 Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory BasicsManisha khan100% (1)

- 2021 Impact of Change Forecast Highlights: COVID-19 Recovery and Impact On Future UtilizationDocument17 pages2021 Impact of Change Forecast Highlights: COVID-19 Recovery and Impact On Future UtilizationwahidPas encore d'évaluation

- Cancer Program SeminarDocument98 pagesCancer Program SeminarhemihemaPas encore d'évaluation

- Med 02 2023Document19 pagesMed 02 2023Nimer Abdelhadi AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Nutri QuizDocument5 pagesNutri QuizAngel Kaye FabianPas encore d'évaluation

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - Market Insights, Epidemiology & Market Forecast-2027 - Sample PagesDocument25 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - Market Insights, Epidemiology & Market Forecast-2027 - Sample PagesDelveInsight0% (1)

- COPD ExacerbationDocument2 pagesCOPD ExacerbationjusthoangPas encore d'évaluation

- Food AllergyDocument2 pagesFood Allergydyfc25Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cardiolab Practical-PharmacologyDocument2 pagesCardiolab Practical-PharmacologyGul HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing Concepts of Care in Evidence Based Practice Townsend 7th Edition Test BankDocument24 pagesPsychiatric Mental Health Nursing Concepts of Care in Evidence Based Practice Townsend 7th Edition Test BankAnitaCareyfemy100% (35)

- "God's Hotel: A Doctor A Hospital, and A Pilgrimage Into The Heart of Medicine" by Victoria SweetDocument43 pages"God's Hotel: A Doctor A Hospital, and A Pilgrimage Into The Heart of Medicine" by Victoria Sweetwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)Document8 pagesCOPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)Emily Anne86% (7)

- A Prelim CAMCARDocument18 pagesA Prelim CAMCARIvan VillapandoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2018 AHA Guidelines For Management of Blood CholesterolDocument66 pages2018 AHA Guidelines For Management of Blood CholesterolsarumaxPas encore d'évaluation

- Luis Andres Arcos Montoya 2014Document11 pagesLuis Andres Arcos Montoya 2014luisandresarcosPas encore d'évaluation

- Hospital Use CaseDocument3 pagesHospital Use Caseprashant gauravPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Questions For HAAD Prometric and DHA For NursesDocument46 pagesSample Questions For HAAD Prometric and DHA For NursesJaezelle Ella Sabale100% (4)

- Perio Case HistoryDocument90 pagesPerio Case HistoryMoola Bharath ReddyPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-691127747Pas encore d'évaluation

- DrugsDocument2 pagesDrugsJeff MarekPas encore d'évaluation

- BASIC PerimetryDocument28 pagesBASIC PerimetryDwi Atikah SariPas encore d'évaluation

- Specification Points - 4.3.1.8 Antibiotics and PainkillersDocument11 pagesSpecification Points - 4.3.1.8 Antibiotics and PainkillersMahi NigamPas encore d'évaluation

- Biolase TimelineDocument19 pagesBiolase Timelinemohamed radwanPas encore d'évaluation

- Heart Rate Variability Today PDFDocument11 pagesHeart Rate Variability Today PDFVictor SmithPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (9)

- Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryD'EverandRewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (157)

- Summary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDD'EverandSummary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (167)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyD'EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsD'EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (39)

- BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: Help Yourself and Help Others. Articulate Guide to BPD. Tools and Techniques to Control Emotions, Anger, and Mood Swings. Save All Your Relationships and Yourself. NEW VERSIOND'EverandBORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER: Help Yourself and Help Others. Articulate Guide to BPD. Tools and Techniques to Control Emotions, Anger, and Mood Swings. Save All Your Relationships and Yourself. NEW VERSIONÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (24)

- Somatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionD'EverandSomatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionPas encore d'évaluation

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesD'EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (70)

- The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeD'EverandThe Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (140)

- The Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeD'EverandThe Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (49)

- Summary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisD'EverandSummary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)

- Don't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksD'EverandDon't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (12)

- Heal the Body, Heal the Mind: A Somatic Approach to Moving Beyond TraumaD'EverandHeal the Body, Heal the Mind: A Somatic Approach to Moving Beyond TraumaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (56)

- The Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItD'EverandThe Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (107)

- Brain Inflamed: Uncovering the Hidden Causes of Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mood Disorders in Adolescents and TeensD'EverandBrain Inflamed: Uncovering the Hidden Causes of Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mood Disorders in Adolescents and TeensÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- Redefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackD'EverandRedefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (152)

- Rapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreD'EverandRapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (17)

- The Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouD'EverandThe Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouPas encore d'évaluation

- Winning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeD'EverandWinning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (559)

- How to Be Miserable: 40 Strategies You Already UseD'EverandHow to Be Miserable: 40 Strategies You Already UseÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (57)

- A Profession Without Reason: The Crisis of Contemporary Psychiatry—Untangled and Solved by Spinoza, Freethinking, and Radical EnlightenmentD'EverandA Profession Without Reason: The Crisis of Contemporary Psychiatry—Untangled and Solved by Spinoza, Freethinking, and Radical EnlightenmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Insecure in Love: How Anxious Attachment Can Make You Feel Jealous, Needy, and Worried and What You Can Do About ItD'EverandInsecure in Love: How Anxious Attachment Can Make You Feel Jealous, Needy, and Worried and What You Can Do About ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (84)

- Binaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationD'EverandBinaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (9)