Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

(Bernard Lonergan) Insight - A Study of Human Understanding

Transféré par

Daniel Pereira93%(15)93% ont trouvé ce document utile (15 votes)

5K vues199 pagesTitre original

[Bernard Lonergan] Insight - A Study of Human Understanding (1)

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

93%(15)93% ont trouvé ce document utile (15 votes)

5K vues199 pages(Bernard Lonergan) Insight - A Study of Human Understanding

Transféré par

Daniel PereiraDroits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 199

INSIGHT

INSIGHT

A Study of Hi

Understandi

nan

BERNARD J. F. LONERC

PHILOSOPHICAL LIBRARY

NEW YORK

Published, 1956, by Philosophical Library Inc CONTENTS

15 East goth Street, New York 16, New York a na

Allright reserved ee ix

PART I

INSIGHT AS A\

I Euasents

bi. The Che

Fit Pai 2, Concepts

This eed ede et ished 1938 2.3. The Lage

2p. Prive Tera

2B tnplict Definition

3

3

7

;

: 43.1, Positive Integers a3

15 Addon Tbh &

34: Fhe HomgenousExpusion q

ST Neat fs Higher Vewp %

34 ls of th lights Viewoin 8

34: Saute Higher Vewpone ¥

35. The signee of Syl z

%

23

Il, Hevusnc Sraucrunss oF Ewpimicat Meriop 2

1. MATHEMATICAL AND SCIENTIIC INSIGHTS COMPARED 8

2, CLASSICAL HEURISTIC STRUCTURES as

Ste An Msteation from Algebra 6

re 6

rental Equations z

35 Invariance a9

4: CONCRETE INFERENCES IRON CLASSICAL LAWS 46

4 STANSTICAL tiURISTIC STRUCTURES 3

442, Elementary Contest 83

sou, ist macro ror, Umar canon a

DenvravUs, HMPRIMATOK + CRORGIUS 1, CHAYES. RUS HBASTOROLE s 6

‘sh, WHSTMONASTERE Dit 338 JUNE, 1958,

.

v.

Contents

‘Tue Canons oF Eemucat, Merion

44, Chasical Lae

42. Suite Tas

6, THE CANON OF stavisticAL RasDUES

6.1. The General Argument

63: The Notion of Abstraction

663, The Abstacines of Clase Laws

64: Symtematie Unification and Imaginative Syathesis

63. The Existence of Statstial Rea

8. The General Character of Stata Theories

7, Indeterminacy and the Nonsystmnatie

‘Tu Comroumvranty oF CLAssicat AND Sramisticat

Investicarions

1.1. Complemencary Hearse Structuces

13) Complementary Procedures

13, Complementary Formulations

14, Complementary Modes of Abstraction

13. Complementarty in Veriition

16. Complementarity it Data Explained

19. Sommary

213. General Characteristic of the View

33. Schemes of Recurrence

253. The Probability of Schemes

24. Emergent Probability

25. Comequencer of Emergent Probability

34. The Aritotclan World View

32, The Galilean World View

4 Iodeterinien =

4. conctusion

Seace AND Tite

2. THE DESCRIPTION OF SPACE AND TINE

21. Extensions and Durations

23, Descriptive Definitions

35, Frames of Reference

34, Transormations

™

6

8

9

&

&

86

°

103

tes

nt

19

40

40

142

vi

vu.

Contents

2.5 Generalized Geometry.

38 A Logial Note.

4 THE ARSTRACT INTELLIGINIETY OF SPACE AND TIME

ji. The Theorem

2. Encl Geometry

33. Absolue Sp

3a. Simelesneity

318 Motion snd Time

36. Principles at lee

4 RODS AND cLocKS

‘tt: The Elementary Paradox

‘12. The Generic Novion of Messurement

13) Diterenistions ofthe Genese Notion

4. THE CONCRETE INTELLIGIBILITY OF SPACE AND ME

Common Sense AND its SuRpECT

2 THE SUBJPCTIVE FIELD OF COMMON sense

23x, Patterns of Experience

23: The Biological Pattern of Experience

24. The Acsthenc Patera of Experience

34. The itllecral Pattern of Experience

255. The Dramatic Peter of Experience

236, Elements in the Dramatic Scject,

2.7. DRAMATIC BIAS

27.4. Represion

273. Inubion

274 Performance

37.8. A Common Problem

276. APiece of Eviden

375. A Note on Met

Conmon Sense as Onjecr

PRACTICAL COMMON SENSE

- INTERSUBJECTIVIFY AND SOCIAL ORDER

3

$. THE Distscric OF cosMUNITY

6

2

8

8.1. The Longer Cycle

82, Implications ofthe Longer Cycle

a. Alternatives ofthe Longer Cycle

BA. Reversal of the Longer Cycle

4 Core sn Reveal

9. conciusion

Vill

IX. Tne Noriow of Juposent

xL

Tunes 245

1. TH GENERAL NOTION OF THE Tin 24s

3.

44 THINos wrrnmn Tinvas

6, SPECIES AS EXPLANATORY

Reriscrive UNDERSTANDING

2. CONCRETE JUDGMENTS OF FACE

4. CONCRETE ANALOGIES AND GENERALIZATIONS

$. COMMON-SENSE JUDGMENTS

4:2. The Soutce of Common-sente Judgments

$3. The Object of Common-enteJudgsnents

$3 Common-snse Judgment std Empire Since

6, PmoBABLE JUDGMENTS

8, mavumearicat JupGMaNts

PART It

INSIGHT AS KNOWLEDGE

Se-ArMMATION OF THE KNower

3

4. SELAFRRMATION

6

8

9. SELFAFRRMATION IN THE POSSIRILITY OF JUDGMENTS OF FACT. 336

Xi

XU.

XIV.

xv.

Contents

Tue Notios oF Bun

4. AY ALL-PERVASIVE NOTION

6. A PUZZLING NoTION

Tue Noniox oF Oxjzcriviry

}. NORMATIVE onjEcriviry

4. ExouenTiaL onjcrvry

‘Tur Meron oF Merarnysics

3. METHOD IN METAMEYSICS

40-THE DIALECTIC OF METHOD 1 METAPHYSIeS

4, Dosti: :

{2 Univeral Do

43. Empiricism

45 Hegelian Ds

{4% Scent Method and Philosophy

Exeaanrs oF Meranitys

2}: ERHLANATORY or

4 Fores

5. Forms

6. "THE NotION oF DEvELOPMEN

" tx. General Not

tic and Intlecusl Dev

7 Hanus Develop

8

38s

38s

396

an

4

434

“7

40

444

4st

458

483

XVI

XVI

XVIIL

Contents

Meravnvsics as Scusice

3. THE MEANING OF THE METAPIYSICAL HLEMENTS

4:4. What are the Metaphysical Element?

32. Cogniional or Ontological Elements?

35. The Nature of Metphsieal Equivalence

4. The Siguficance of Metaphysical Equivalence

4. Ti UNITY OF PROPORTIONATE BEING

41. The Unity of the Proportonate Univente

42. The Unity ofa Goncte Be

$3. The Unity of Man

42 Summary

Merapaysics 4s Diatecric

tot The Sense of the Unknown,

12. The Genes of Adequate Sl knowledge

3. Mythic Consciousness

4 Myth and Metaphysics

5. Myth and Allegory

18 The Notion of Mystery

21. The Criterion of Truth

The Definition of rath

23. The Ontalogial Aspect of Truth

34. Truth and Expresion

3. The Appropraon of Trath

Bi. The Problem

3. The Notion of a Univeral Viewpoint

33. Levels and Sequeuces of Expresaon

314 Limitations ofthe Treat,

3. Interpretation and Method

36, The Sketch

Some Canons for 2 Methodical Hermeneutics

Tur’ Possmury oF Exines

1. Leveh ofthe Good

13. The Notion of Wil

14 The Method of Ethics

ES The Ontology ofthe Good

21. The Significance of Staiical Reidvet

3.3, The Underlying Seraitive Flow

23. The Prac sight

488

488

499

407

3

fe

s30

su

as

49

362

i

595

395

96

6o7

608

Contents

1 set and fete Fedor

3 Gitdoe of Etecre Bestom

3: bone Fancons of Stee and Haron

2 Nan inpsene

3 Te retn of iberson

XIX. Generar TRANscENDENT KNOWLEDGE

XX, SreciaL Transcenpanr Knowispce

s

6.

Emocuz

Txpex

43, The Genctal Context of Belief

12. The Analysis of Belief

43. The Critique of Bele

44: A Logieal Note

RISUMPTION OF THE HEURISRC STRUCTURE OF THE SOLUTION

‘THE IDENTIFICATION OF THEE SOLUTION

PREFACE

[reise der is given all the ¢

spot the criminal. He may ad

10 each clue as it arises. He needs

tery. Yethec

smain in the dark for

no further clues to sol

the simple reason that reaching

not the mere m

the solution is not the mere apprely

mory of all, but a quite distinct

at places the full set of clues in a

sion of any clu

activity of organizing intelligence

unique explanatory perspective.

By insight, then, is meant not any act of atention or a

memory but the supervening act of understanding. It is not

condite intuition but the familiar eventthat occurs easily and

in the moderately intelligent, rarely and with difficulty onk

stupid. In iself itis so simple and obvioas that it seems to merit the little

attention that commonly it receives. At che same time, its function in

cognitional activity is so central that co grasp it in its conditions, its

working, and its result, is to confer a basic yet startling unity on the

whole fickd of human inguiry and human opinion. Indeed, this very

wealth of implications is disconcerting, and L find it difficult to state

anny brief and easy manner what the present book is about, how a single

author can expect to treat the variety of topics listed in the table of

contents, why he should attempt to do so in a single work, and what

pe to accomplish even were he to succeed in his odd

good he could h

undertaking,

Still, preface shou! provide at eas jejune and sim

to such questions and, perhaps, I can make a beginning by saying that

the aim of the work is to convey an insight into insight. Mathematicians

seck insight into sets of elements. Sciestists seek insight into ranges of

phenomena. Men of common sense seck insight into concrete situations

and practical affairs. But our concern isto reach the act of organizing

{intelligence thac brings within a single perspective the insights of mathe

nen of common sense

ified answer

tmaticians, scientist

Ie follows at once that the topics listed in the table of contents are not

$0 disparate as they appear on a superficial reading. Ifanyone wishes to

become a mathematician or a scientist or a man of common sense, he

will detive no direct help from the present work. As physicists study

x Preface

the shape of waves and leave to chemists the analysis of air and water,

so we'are concerned not with the objects understood in mathematics

but with mathematicians’ acts of understanding

stood in the various sciences but with scientists’ acts of understanding,

not with the concrete situations mastered by common sense but with

the acts of understanding of men of common sense

Further, while all acts of understanding have a certain family like-

ness, 2 full and balanced view is to be reached only by combining in a

single account the evidence obtained from different fields of intelligent

activity. Thus, the precise nature of the act of understanding is to be

seen most clearly in mathematical examples. The dynamic context in

which understanding occurs ean be studied to best advantage in an

investigation of scientific methods. The disturbance of that dynamic

‘ontext by lien concernsis thrust upon one's attention by the manner in

which various measures of common nonsense blend with commonsense.

However, insight is not only a mental activity but also a constituent

factor in human knowledge. It follows that insight into insight is in

some sense a knowledge of knowledge. Indeed, itis a knowledge of

knowledge that seems extremely relevant to a whole series of basic

problems in philosophy. This I must now endeavour to indicate even

though I can do so only in the abrupt and summary fashion that leaves

terms undefined and offers arguments that fll far short of proof.

First, then, itis insight that makes the difference between the tan-

talizing problem and the evident solution, Accordingly, insights seem

to be the source of what Descartes named clear and distinct ideas and,

con that showing, insight into insight would be the source of the clear

and distinet idea of clear and distinct ideas.

Secondly, inasmuch as it is the act of organizing intelligence, insight

is an apprchension of relations. But among relations are meanings, for

meaning seems to be a relation between sign and signified. Insight,

then, includes the apprehension of meaning, and insight inco insight

includes the apprehension of the meaning of meaning.

Thirdly, in a sense somewhat different from Kar

both a priori and syr

merely given to sense of to empirical consciousness. Irs synthetic, for ie

adds to the merely given an explanatory unification or organization,

Te seems to follow that insight into insight will yield a synthetic and a

priori account of the full range of synthetic, a priori components in our

cognitional activity.

not with objects under

ight is

tic. It is a priori, for it goes beyond what is

Preface xi

Fourthly, a unification and organization of other departments of

Knowledge is a philosophy. But every insight unifies and organizes.

Insight into insight, then, will unify and organize the insights of mathe-

‘aticians, scicntists, and men of common sense. Ir seems to follow that

insight into insight will yield a philosophy.

Fifthly, one cannot unify and organize knowing without concluding

to a unification and organization of the known. But a unification and

organization of what is known in mathematics, in the sciences, and by

Peron entra meaphysics, Hence, in tas mena tha ing into

insight unifies and organizes all our knowing, it will imply a meta~

physics.

Sixthly, the philosophy and metaphysics chat result from insight into

insight will be verifiable. For just as scientific insights both emerge and

are verified in the colours and sounds, tastes anc odours, of ordinary

experience, so insight into insight both emerges and is verified in the

insights of mathematicians, scientists, and men of common sense. But

if insight into insight is verifiable, chen the consequent philosophy and

metaphysics will be verifiable. In other words, just as every statement

in theoretical science can be shown to imply statements regarding

sensible fact, so every statement in philosophy and metaphysics can be

shown to imply statements regarding cognitional ct

Seventhly, besides insights there are oversights. Besides the dynamic

context of detached and disinterested inquiry in which insights emerge

with a notable frequency, there are the contrary dynamic contexts of

the fight from understanding in which oversights occur regularly and

‘one might almost say systematically. Hence, ifinsight into insight isnot

to be an oversight of oversights, it must include an insight into the

principal devices of the Hight from understanding

Eighthly, the fight from understanding will be seen to be anything

but a peculiar aberration thae afflicts only the unfortunate or the per-

Verse, In its philosophic form (which is not to be confused with its

psychiatric, moral, social, and cultural manifestations) it appeats to

result simply from an incomplete development in the intelligent and

reasonable usc of one’s own intelligence and reasonableness. But though

its otigin is a mere absence of full development, its consequences are

Positive enough. For the flight from understanding blocks the occus~

rence of the insights that would upset its comfortable equilibrium. Not

fs it content with a merely passive resistance. Though covert and de-

vious, it is resourceful and inventive, effective and extraordinarily

xi Preface

plausible, fe admits a vast variety of forms and, when it finds some un-

tenable, it can resort to others. If it never refuses to supply su

‘minds with superficial positions, it is quite com

philosophy so acute and profound that the elect strive in vain and for

centuries to lay bare its real inadequacies.

‘Ninthly, just as insight into insight yields a clear and distinct idea

lear and distinct ideas, just as it includes an apprehension of the mean-

ing of meaning, just as it exhibits the range of the a priori, synthetic

components in our knowledge, just a it involves a philosophic uni

tion of mathematics, the sciences, and common sense, just as it implies

of what is to be known through the various de-

perficial

etent to work out a

a metaphysical accoun

partments of human inquiry, so also insight into the various modes of

the flight from understanding, will explain

(1) the range of really confused yet apparently clear and distinct

ideas,

(2) aberrant views on the meanin,

‘meaning,

(5) distortions in the a prior, synthetic components in our know-

ledge,

(4) the existence of a multiplicity of philosophies, and

(5) the series of mistaken metaphysical and anti-metaphysical posi-

tions.

Tenthly, there seems to follow the possibility of a philosophy that is

at once methodical, critical, and comprehensive. It will be compre-

hensive because it embraces in a single view every statement in every

philosophy. Ie will be critical because it discriminates between the pro-

ducts of the detached and disinterested desire to understand and, on the

other hand, the products of the flight from understanding, It will be

methodical because it transposes the statements of philosophers and

metaphysicians to their origins in cognitional activity and it settles

whether that activity is or is not aberrant by appealing, not to philo~

sophers, not to metaphysicians, but to the insights, methods, and pro-

cedures of mathematizians, scientists, and men of common sense.

“The present work, then, may be said to operate on three levels. It isa

study of human understanding. Ie unfolds the philosophic implications

‘of understanding. Its a campaign against the fight from understand-

ing. These thre: ‘Without the first there would be

no base for the second and no precise meaning for the third. Without

the second the first could not get beyond elementary statements and

rls are soli

Preface xii

there could be no punch to the third. Without the third the second

would be regarded as incredible and the fitst would be neglected,

Probably I shall be told that I have tried to operate on too broad a

front. But Iwas led to do so for two reasons. In consteucting a ship or a

philosophy one has to go the whole w fort that is in principle

incomplete is equivalent to a failure, Moreover, against the flight from,

understanding half measures are of no a

strategy can be successful, To disregard any sto

from understanding is to

offensive promptly will be

If however, these consid nnted, it still will be urged that

what I have attempted could b properly only by the organ-

ized research of specialists in many different fields. This, of course, 1

cannot but admit. Iam far from competent in most of the many fields

in which insights occur, and I could not fail to welcome the impressive

assembly of talent and the comforting allocation of funds associated

swith a research project. But I was not engaged in what commonly is

meant by research. My aim was neither to advance mathematics not to

contribute to any of the specialized branches of science but to seek a

common ground on which men of intelligence might meet. It scemed.

necessary to acknowledge that the common ground I envisaged was

rather impalpable at atime when neither mathematicians nor scientists

nor men of common sense were notably articulate on the subject of in-

sight, What had to be undertaken was a prcliminary, exploratory jour-

ney into an unfortunately neglected region. Only after specialists in

different fields had been given the opportunity to discover the exist

ence and significance of their insights, could there arise the hope that

some would be found to discern my intention where my expression

‘was at fault, to correct my errors where ignorance led me astray, and

with the wealth of their knowledge to fill the dynamic but formal

structures I tried to erect. Only in the measure that this hope is realized,

will there be initiated the spontaneous collaboration that commonly.

aust precede the detailed plans of an organized investigation,

‘There remains the question, What practical good can come of this

book? The answer is more forthright than might be expected. For in=

sight is the source not only of theoretical knowledge but also of all its

practical applications and, indeed, ofall intelligent activity. Insight into.

insight, then, will reveal what activity is intelligent, and insight into

‘oversights will reveal what activity is unintelligent, But to be practical

I. Only a comprebensive

nighold of the fight

ct. a base from which a counter~

xiv Preface

is to do the intelligent thing and to be unpractical isto keep blundering

about. It follows that insight into both insight and oversight is the very

key to practicality

‘Thus, insight into insight brings to light the cumulative process of

progress. For concrete situations give rise to insights which issue into

policies and courses of action. Action transforms the existing situation

to give rise to further insights, better policies, more effective courses of

action. Ic follows that if insight occurs, it keeps recurring; and at each

recurrence knowledge develops, action increases its scope, and situa-

tions improve

‘Similarly, insight into oversight reveals the cumulative process of

decline, For the flight from understanding blocks the insights that con-

crete situations demand. There follow unintelligent policies and inept

courses of action. The situation deteriorates to demand still further in~

sights and, a they are blocked, policies become more unintelligent and

action more inept. What is worse, the deteriorating situation seems to

provide the uncritical, biased mind with factual evidence in which the

bias is claimed to be verified. So in ever increasing measure intelligence

comes to be regarded as irrelevant to practical living. Human activity

settles down to a decadent routine, and initiative becomes the privilege

of violence.

Unfortunately, as insight and oversight commonly are mated, s0 also

are progress and decline. We reinforce our love of truth with a prac

ticality that is equivalent to an obscurantism. We correct old evils with

2 passion that mars the new good. We are not pure. We compromise

‘We hope to muddle through. But the very advance of knowledge

brings a power over nature and over men too vast and terrifying to be

entrusted to the good intentions of unconsciously biased minds. We

have to lean to distinguish sharply between progress and decline,

learn to encourage progress without puting a premium upon decline,

Jeam to remove the tumour of the flight from understanding without

destroying the organs of intelligence.

No problem is at once more delicate and more profound, more prac-

tical and pethaps more pressing. How, indeed, is 2 mind to become

‘conscious ofits own bias when that bias springs from a communal fight

from understanding and is supported by the whole texture of a civiliza

tion? How can new strength and vigour be imparted to the detached

and disinterested desire to understand without the reinforcement acting

as an added bias? How can human intelligence hope to deal with the

tt”

Preface x

relligible yet objective situations which the fight from under

ding creatzs and expands and sustains? At least, we can make a be-

ing Dy asking what precsely iti to understand, what are the

$Fynamics ofthe flow ofconciousnes that favours insight, what are the

ftyerferences that favour oversight, what, finally, do the answers to

Such questions imply forthe guidance of human thought and action

Tmust conclude. There will be offered in the Iniraduction a more exact,

account of the aim and structure of this book. Now I have to make a

brief acknowledgement of my manifold indebtedness, and naturally 1

don led to think in the first place of the teachers and writers who have

ief their mark upon me in the course of the twenty-eight years that

Ihave elapsed since I was introduced to philosophy. But so prolonged

Jhas been my search, so much of ic has been a dark struggle with my own

flight from understanding, so many have been the halF-lights and de-

tours in my slow development, that my sincere gratitude ean find no

brief and exact yet intelligible expresion. I turn, accordingly, to list

more palpable benefactors: the staff of L'Immaculée Conception in

Montreal where the parallel historical investigation* was undertaken;

the staff of the Jesuit Seminary in Toronto where this book was

written; the Rev, Eric O'Connor of Loyola College, Montreal, who

‘was ever ready to allow me to draw upon his knowledge of mathe-

tmatics and of science; the Rev. Joseph Wolftange, the Rev. Joseph

Glark, the Rev. Norris Clarke, the Rev. Frederick Crowe, the Rev

Frederick Copleston, and the Rev. André Godin who kindly read the

typescript and by their diversified knowledge, encouraging, remarks

and limited criticisms permitted me to feel that 1 was not entirely

‘wrong; the Rev. Frederick Crowe who has undertaken the tedious tak

‘of compiling an index.

NOTE TO SECOND EDITION

_Thave recast the last fifteen lines on page 66, the first two on page 67,

lines 15 to 31 on page 98, the first rwelve lines on page 111, and the

passage running from line 24 page 340 to line 12 page 341

The Concept of Veram inthe Writings of St Thomas Aquinas’ Theological S

yomas Aquina” Theol

(Woodstock, Md), VIE (146), 349-92: VII (1947). 35-70, 404-44: X (1949).

393

INTRODUCTION

he aim of the present work may be bracketed by a series of dis-

{junctions Inthe fist place, the question isnot whether knowledge

‘exists but what precisely i its nature. Secondly, while the content of the

known cannotbe disregarded, sil itis tobe treated only inthe schematic

and incomplete fashion needed to provide a discriminant or determinant

of cognitive acts. Thirdly, the aim is not to set forth alist of the abstract

properties of human knowledge but to assist the reader in effecting a

personal appropriation of the concrete, dynamic structure immanent

and recurrently operative in his own cognitional activities. Fourthly,

such an appropriation can occur only gradually, and so there will be

offered, not a sudden account of the whole of the structure, but a slow

ascmbly of its elements, relations, altematives, and implications.

Fifthly, the order of the assembly is governed, not by abstract consider

ations of logical or metaphysical priority, but by concrete motives of

pedagogical efficacy

The programme, then, is both concrete and practical, and the

motives for undertaking its execution reside, not in the realm of easy

‘generalities, but in the difficult domain of matters of fact. If, at the end

of the courte, the reader will be convinced of thote facts, much will be

achieved; but at the present moment all I can do is to clatify my inten

tions by stating my belief. I ask, accordingly, about the nature rather

than about the existence of knowledge because in each of us there exist

two different kinds of knowledge. They are juxtaposed in Cartesian

dualism with its rational ‘Cogito, ergo sun’ and with its unquestioning

cextroversion to substantial extension. They ate separated and alienated

in the subsequent rationalist and empiricist philosophies. They are

brought together again to cancel each other in Kantian criticism. If

these statements approximate the facts, then the question of human

knowledge is not whether it exists but what precisely are its two diverse

forms and what are the relations between them. If that & the relevant

question, then any departure from itis, in the same measure, the mis-

fortune of missing the point. But whether or not that is the relevant

question, can be settled only by undertaking an arduous exploratory

Journey through the many fields in which men succeed in knowing or

attempt the task but fail.

xviii Introduction

Secondly, an account of knowing cannot disregard its content, and

its content is so extensive that it mocks encyclopaedias and overflows

libraries; its content is so diffcule that a man does well devoting his life

to mastering some part of it; yet even so, its content is incomplete

subject to further additions, inadequate and subject to repeated, Future

revisions. Does it not follow that the proposed exploratory journey

not merely arduous, but impossible? Certainly it would be impossible,

atleast for the writer, ifan acquaintance with the whole range of know-

ledge were a requisite in the present inquiry. Bue, in fact, our primary

concern is not the known but the knowing. The known is extensive,

but the knowing isa recurrent structure that can be investigated sufi-

ciently ina series of strategically chosen instances, The known is dificult

to master, but in our day competent specialists have laboured to select

for serious readers and to present to them in an adequate fashion the

basic components of the various departments of knowledge. Finally,

the known is incomplete and subject to revision, but our concern is the

kanower that will be the source of the future additions and revisions.

I will not be amiss to add a few corollaries, for nothing disorientates

a reader more than a failure to state clearly what a boo is not about.

Basically, then, this is not a book on mathematics, nor a book on

science, nor a book on common sense, nor a bock on metaphysics;

indeed, in a sense, itis not even a book about knowledge. On a first

level, the book contains sentences on mathematics, on science, on

common sense, on metaphysics. On a second level, the meaning of all

these sentences, their intention and significance, are to be grasped only

by going beyond the scraps of mathematics or science or common

sense or metaphysics to the dynamic, cognitional structure that is ex~

cemplified in knowing them. On a thitd level, the dynamic, cognitional

structure to be reached is not the transcendental ego of Fichtean specula~

tion, nor the abstract pattern of relations verifiable in Tom and Dick

and Harry, but the personally appropriated structure of one’s own ex=

periencing, one’s own intelligent inquiry and insights, one’s own

critical reflection and judging and deciding. The crucial issuc is an ex

perimental issue, and the experiment will be performed not publicly

but privately. I¢ will consist in one’s own rational selfconsciousne:

clearly and distinctly taking possession of itself as rational self-conscio

ness. Up to that decisive achievement, all leads. From it, all follows, No

cone else, no matter what his knowledge or his eloquence, no matter

what his logical rigour or his persuasiveness, can do it for you, But

Introduction xix

h the act is private, both its antecedents and its consequents have

their public ‘nanifeation. There ean be long series of matks on paper

har communicate an invitation to know oneself in the tension of the

duality of one’s own knowing; and among such series of marks with

sn invitatory meaning the present book would wish to be numbered.

Nor need it remain a secret whether such invitations are helpful or,

when helpful, accepted. Winter twilight cannot be mistaken for the

though

summer noonday sun.

In the third place, then, more than all els, the

Jssue an invitation toa persona, decisive at. But the very nature of the

set demands that it be understood in itself md in its implications. What

3s? What is meant by in-

im of the book is to

‘on earth is meant by rational self-conscious:

‘iting i to take possession of itself? Why is such self-possession said to

be so decisive and momentous? The questions are perfectly legitimate,

but the answer cannot be brief.

However, it is not the answer itself that counts so much as the

‘manner in which it is read. For the answer cannot but be written in

swords; the words cannot but proceed from definitions and correlations,

analyses and inferences; yet the whole point of the present answer

‘would be missed if a reader insisted on concluding that I must be en-

gaged in setting forth lists of abstract propertics of human knowing.

‘The present work is not to be read as though i described some distant

region ofthe globe, which the reader never visited, or some strange and

‘mystical experience, which the reader never shared. Its an account of

knowledge. Though I cannot recall to eac’ reader his personal experi

fences, he can do so for himself and therety pluck my general phrases

from the dim world of thought to sct them in the pulsing flow of life.

‘Again, in such fields as mathematics and natural science, i is posible to

delineate with some accuracy the precise content of a precise insight;

but the point of the delineation is not to provide the reader with a

stream of words that he can repeat to others or with aset of terms and

relations from which he can procced to draw inferences and prove con

clusions. On the contrary, the point here, as elsewhere, is appropria~

tion; the point is to discover, to identify, to become familiar with the

Activities of one’s own intelligence; the point is to become able to dis

ctiminate with ease and from personal conviction between one’s purely

intellectual activities and the manifold of other, ‘existential’ concerns

that invade and mix and blend with the operations of intellect to render

itambivalent and its pronouncements ambiguows.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Sorrows of Young Werther, by J.WDocument55 pagesThe Sorrows of Young Werther, by J.WDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Illiad: "Jimmy It Down" - Dumb It Down Simplify ItDocument1 pageThe Illiad: "Jimmy It Down" - Dumb It Down Simplify ItDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Christian ParticularismDocument98 pagesChristian ParticularismDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical JesusDocument168 pagesHistorical JesusDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- How Deep Is Your LoveDocument2 pagesHow Deep Is Your LoveDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Teresa D'AvilaDocument4 pagesSt. Teresa D'AvilaDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Historical JesusDocument168 pagesHistorical JesusDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Monday - Chest: Pulley/ Rope Cable Rev. Grip Bar Press Testa Polia (Ou Francês Polia) Coice - Overhead Bench/ ParalelaDocument1 pageMonday - Chest: Pulley/ Rope Cable Rev. Grip Bar Press Testa Polia (Ou Francês Polia) Coice - Overhead Bench/ ParalelaDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Isaiah 5.7Document1 pageIsaiah 5.7Daniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Poemata Secunda ParsDocument7 pagesPoemata Secunda ParsDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Poemata Secunda ParsDocument7 pagesPoemata Secunda ParsDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Padre PioDocument1 pageSt. Padre PioDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- A Song On FloDocument1 pageA Song On FloDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument3 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Workout RoutineDocument4 pages2017 Workout RoutineDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- TS Eliot The WastelandDocument18 pagesTS Eliot The WastelandAlex CasperPas encore d'évaluation

- المغالطات المنطقية الDocument60 pagesالمغالطات المنطقية الHamada AhmedPas encore d'évaluation

- TRIVIUM (Grammar, Logic, & Rhetoric) - Initial Study PlanDocument27 pagesTRIVIUM (Grammar, Logic, & Rhetoric) - Initial Study PlanvictorcurroPas encore d'évaluation

- StevenSnyder SpeedReading PDFDocument42 pagesStevenSnyder SpeedReading PDFDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Padre PioDocument1 pageSt. Padre PioDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Verse 1Document1 pageVerse 1Daniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Daniels Personal LibraryDocument18 pagesDaniels Personal LibraryDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Chest Back Shoulders Lower Body Biceps Triceps Shoulders: MON TUE WED THU FRI SATDocument4 pagesChest Back Shoulders Lower Body Biceps Triceps Shoulders: MON TUE WED THU FRI SATDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Do Not Go Gentle Into That GoodnightDocument1 pageDo Not Go Gentle Into That GoodnightVivian GrockitPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Teresa D'AvilaDocument4 pagesSt. Teresa D'AvilaDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Verse 1Document1 pageVerse 1Daniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Padre PioDocument1 pageSt. Padre PioDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- KeywordsDocument17 pagesKeywordsDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- St. Padre PioDocument1 pageSt. Padre PioDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- How Deep Is Your LoveDocument2 pagesHow Deep Is Your LoveDaniel PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Wōden Wōdan Wuotan WōtanDocument2 pagesWōden Wōdan Wuotan WōtanErika CalistroPas encore d'évaluation

- Story of BeninDocument3 pagesStory of BeninDante Sallicop0% (1)

- School 131021 NominalRoll IN REG PDFDocument37 pagesSchool 131021 NominalRoll IN REG PDFMy IndiaPas encore d'évaluation

- PJP - Codding Assessment ScoresDocument23 pagesPJP - Codding Assessment Scoressubham bhutoriaPas encore d'évaluation

- We Believe by Newsboys Chords - DDocument2 pagesWe Believe by Newsboys Chords - Drotaryking100% (1)

- Rays From The Life of Imam Hasan Bin Ali (As)Document53 pagesRays From The Life of Imam Hasan Bin Ali (As)بندہء خداPas encore d'évaluation

- Rosary For The Faithfully DepartedDocument18 pagesRosary For The Faithfully DepartedLIC2ill88% (8)

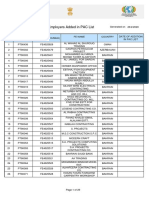

- List of Employers Added in PAC ListDocument29 pagesList of Employers Added in PAC ListCharles DanielPas encore d'évaluation

- Friends - (5x05) - The One With The KipsDocument6 pagesFriends - (5x05) - The One With The Kipskrishna chaitanyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Tourism PresentationDocument17 pagesPhilippine Tourism PresentationJulie Rose DS BaldovinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Caracalla and Alexandrian Troubles in PapyrusDocument9 pagesCaracalla and Alexandrian Troubles in PapyrusScott KennedyPas encore d'évaluation

- Bare - Script (2012) PDFDocument126 pagesBare - Script (2012) PDFLeonardo Cipriano G. Gomes100% (2)

- The Bahima Century Dynasty - BCDDocument7 pagesThe Bahima Century Dynasty - BCDJames Gray100% (1)

- Workbook Unit 15: Osciel Sánchez PachecoDocument12 pagesWorkbook Unit 15: Osciel Sánchez PachecoOscielSanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- In The Name of JEHOVAH - Testimony of Prophet Jeshuruni of Ancient ProphecyDocument4 pagesIn The Name of JEHOVAH - Testimony of Prophet Jeshuruni of Ancient ProphecyBheka Chyren Jeshuruni ShabalalaPas encore d'évaluation

- Singapore-malaysia-Indonesia Itinerary (June 4-11,2016) - DraftDocument14 pagesSingapore-malaysia-Indonesia Itinerary (June 4-11,2016) - DraftHij PacetePas encore d'évaluation

- Francfort Et Tremblay, Marhasi Et La Civilisation de L'oxus PDFDocument175 pagesFrancfort Et Tremblay, Marhasi Et La Civilisation de L'oxus PDFneobirt750% (2)

- Promo Langkawi - Trip 2Document3 pagesPromo Langkawi - Trip 2Husaini HalilPas encore d'évaluation

- Chinese Capitalism in Dutch JavaDocument21 pagesChinese Capitalism in Dutch JavaBanyolan GilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Dead Stars (Powerpoint)Document26 pagesDead Stars (Powerpoint)Vier Gentalian100% (2)

- Prayer Letter - November 2Document1 pagePrayer Letter - November 2JonPas encore d'évaluation

- 01 Sujets Session Anglais BepcDocument60 pages01 Sujets Session Anglais BepcLe Coréen Roméo50% (2)

- Form Resume Kajian Walimurid 2023 01 27Document3 pagesForm Resume Kajian Walimurid 2023 01 27Brama KumbaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Partying Is Such Sweet Sorrow ScrpitDocument3 pagesPartying Is Such Sweet Sorrow Scrpitapi-553175091Pas encore d'évaluation

- List of Secretary Union Councils District Sialkot No. & Name of Union Council Name of Secretary UC Cell NumbersDocument8 pagesList of Secretary Union Councils District Sialkot No. & Name of Union Council Name of Secretary UC Cell NumbersAhmed MaherPas encore d'évaluation

- Indigenous Peoples of The Americas - WikipediaDocument21 pagesIndigenous Peoples of The Americas - WikipediaRegis MontgomeryPas encore d'évaluation

- B.D.O Performance StatusDocument177 pagesB.D.O Performance Statuschandra kandpalPas encore d'évaluation

- Lyrics Big BangDocument36 pagesLyrics Big BangkranalanpagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Welcome To World's Longest Website - Growing With Every New Visitor!4Document1 pageWelcome To World's Longest Website - Growing With Every New Visitor!4Owner JustACodePas encore d'évaluation

- Emp Notice MSC Web 43 Direct-Ii Dated 13102020 PDFDocument317 pagesEmp Notice MSC Web 43 Direct-Ii Dated 13102020 PDFFlip ThirteenPas encore d'évaluation