Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Research Paper

Transféré par

api-242138226Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Research Paper

Transféré par

api-242138226Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Inclusion: Special Education Quality vs.

Equality

Abstract This paper will discuss and critique the educational effects that inclusion of special needs students in a general education classroom has on all students. Inclusion appears to be a just and fair way to provide equal education to all students, but it is not the most effective method for providing a quality education. While inclusion does create equal education across all levels of students and seems to be the easiest way to deal with students with disabilities, the ultimately decreased quality of education has an overall negative affect on both handicapped and nonhandicapped students in the classroom. Through the research of the effects of inclusion on graduation and college attendance rates as well as a discussion of the pros and cons of inclusive teaching methods, this paper will argue that the benefits of inclusion do not nearly outweigh its costs. The way that schools approach varying ability levels needs to be examined and reformed in order to provide the highest quality education to each individual student.

Introduction One of the current debates in the world of education and particularly in the world of special education is inclusion, also known as mainstreaming. In practice, inclusion means keeping students with special behavioral or learning needs in the traditional classroom with the rest of their classmates as opposed to separating them into specialized groups or classes. The Individuals with Disabilities Act of 1990, which stemmed from the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, was set in place to guarantee students with disabilities access to a free appropriate public education (Kurtzig Freedman, 1). While these acts have changed

the face of special education over the past few decades, the idea of an appropriate public education has been difficult to define. A common practice today to ensure an equal education for all students has to been to use inclusion. Mainstreaming education in this way technically fulfills the requirements of the Individuals with Disabilities Act; however, what it is missing is a fair and quality education for all students in the classroom. Inclusion is considered the most successful method of teaching at this point in time, but beyond lacking academic success, there is evidence that suggests that many educators do not even implement its methods. While inclusion may allow for an equal education and seems to be the easiest way to deal with students with disabilities, the decreased quality of education has an overall negative affect on both handicapped and non-handicapped students in the classroom.

Pros & Cons The reasoning behind mainstreaming education with inclusion of special needs students is valid. By not separating the students based on their abilities or disabilities, schools are providing an equal education to all students without the risk of discrimination accusations. Inclusion is also a less expensive way for school systems to address the special needs students because it requires fewer staff members if there are no teachers that specifically teach special education. It is important, however, to weigh the benefits against the costs of this method.

Graduation and Academic Success Rates It would be expected that inclusion would not have any substantial effects of the graduation rates of average students. It would also be expected, hopefully, that inclusion would significantly increase the graduation rates of students with special needs. One study conducted in Georgia

over the course of 6 years observed the records of more than 67,000 students identified as having mild disabilities in order to measure the effects of inclusion on graduation rates (Goodman et al., 241). The overall results of the study showed that more time spent in a traditional, inclusive classroom increased the graduation rate of these students by less than 1% (Goodman et al., 247). Without substantial graduation rate success, the efforts made for inclusion are more or less wasted.

Effects on Emotional Well-Being Perhaps the most affective aspects of inclusion are the emotional benefits for students. By including students with disabilities in the classrooms sitting next to their peers that may not have disabilities, the stigma or negative perception of special education students is greatly reduced. Students do not feel singled out for being different or handicapped by not being able to participate in class in the same ways as their peers (Murphy, 481). Even though inclusion has the ability to benefit the comfort level of special needs students by keeping them with their fellow classmates, there are still instances where a students emotional well-being is negatively affected by bullying or victimization that can occur in traditional school settings. Disabled students in inclusive classroom settings tend to be at higher risk of social isolation and rejection by their classmates (Murphy, 481). Schooling is always an emotionally challenging time for a large number of students, but whatever teaching method is put in place should not add to this emotional discomfort or decreased social well-being.

Effects on Both Average and Special Needs Students

Average students in an inclusive classroom may benefit socially by the exposure to students that may be different from themselves (Murphy, 482). When children are introduced to people with disabilities at a young age, it is expected that they are better prepared to interact with and accept those that may look, act, or think differently from them. While the attitudes of average students towards their special needs peers are important to consider, it is also worth mentioning the exposure of special needs students to more than just other students with special needs. Socially, inclusion has positive effects for all students. However, by attempting to protect the emotional well-being of students, the overall quality of education is jeopardized. Inclusion has a negative effect on all students in a mainstreamed classroom. The students in the classroom who do not require special attention or methods are forced to learn at a slower pace or in a different style when the teacher has to adapt the curriculum to suit the students in the classroom who perhaps cannot keep up. In an alternate scenario, if a teacher does not slow down or change how he or she is teaching in order to be helpful to the greatest number of students, the students with special needs may not be able to understand or keep up, therefore having to struggle in the classroom. If students with learning disabilities or special needs cannot actively keep up or participate in what is happening in class, then they are not actually being included.

Why Doesnt Inclusion Work? In order for inclusion to be considered a successful method of teaching, there needs to be evidence that supports the idea that it makes the learning experience for all students more successful. There also needs to be evidence of the correct use of inclusion and studies to provide evidence of its effects. Without proof or practical use, it cannot be argued that inclusion is the most beneficial method of providing education to all students. Even when there is some a certain

level of evidence of success, it must be analyzed for its ability to substantially affect student learning outcomes.

Lack of Evidence of Success Research and case studies do not provide evidence to support that inclusion provides appropriate education to students. There is not enough evidence that suggests that inclusion has a beneficial effect on the academic performance or success of students. It is an unfortunate fact that graduation rates are low for student with disabilities, but the graduation rate study conducted in Georgia demonstrated over the course of 6 years that even with a 62% increase in inclusion of students with mild disabilities, the graduation rate for these same students increased by just 0.4% (Goodman et al., 248). Another study that focused specifically on students with autism found that those that spent 75% of their time in an inclusive classroom setting were no more likely to attend college than those students with autism that were not taught in an inclusive classroom (Foster and Pearson, 183-184). If methods of inclusion are not significantly increasing graduation rates or college attendance, then it cannot be considered a successful method of education for any students.

Lack of Actual Use in Practice Having to find a balance between going slow enough for special needs students but fast enough for average learners may be unfair to a teacher that is trying their best to make sure all students with varying abilities are learning at an appropriate rate and level, again raising the question: how do we define appropriate? Because of the use of inclusion, there has been an increase of special needs students in general education classrooms; it has been recommended that teachers

implement collaborative teaching practices but studies have shown that many teachers do not use these practices in their classrooms (Damore and Murray, 241). It is difficult to have one set guideline of teaching practices for an environment that is argued to be unique depending on student ability. Even when teachers are willing to take on this task, many of them are not trained or even aware of how to work with students with special needs or how certain disabilities affect their learning abilities (Bricker, 188). Many education professionals agree with the conceptual and moral reasons that support inclusion but then tend to overlook the practical implementation of its methods in the classroom (Bricker, 192). One study in Colorado of 246 educators from 22 schools found that 28% of respondents believed that inclusion would be detrimental to the education of other students and that more than 50% said that inclusion of special students would create too much additional work for staff (Murphy, 483). Even if inclusion were argued to be a significantly successful program, an argument for which there is little evidence to support, without practical execution, it can never be effective.

Proposed Solution It is evident that inclusion of students with disabilities is not the best way to teach any student. A system of special education that matches student ability with an appropriate instructional method is required in order to provide the highest quality education possible (Kauffman et al., 3). The implementation of a system that is broken down by level and ability could work to reduce the stigma of special education. If all students are placed into groups or classes based on their abilities, then it becomes the accepted way of how things work, rather than the idea that all students except for those with disabilities are included in the traditional classroom. There should not be a traditional classroom; because all students learn differently, classroom teaching styles

should vary accordingly. Because of all of the research that points to the emotional and social benefits of inclusion, there should be some aspects of education that incorporates this aspect of the practice. A combination of mixed classrooms for certain subjects as well as classrooms separated by level for other subjects would be a successful way to give all students the specific education they need but also the emotional stimulation of being exposed to students of a variety of levels and abilities.

Discussion Inclusion sounds fair and just in theory, but in practice this method does not accomplish the overall goals of school and does not provide appropriate education. Is the equality of education actually more important than the quality of education that each student receives? With individual and unique talents, abilities, and skills should come individual and unique teaching methods. Unfortunately, by grouping students together through inclusion, many of them are set up for failure because of how different every student is (Kauffman et al., 2). Providing specialized education to students based on their learning levels and abilities requires extra effort, more innovation, and sometimes extra money from the schools. It is important to remember that this extra effort is guaranteed by the Individuals with Disabilities Act of 1990; that effort and innovation is what makes for an appropriate education for all students (Kurtzig Freedman, 1).

Conclusion

A method where all students are taught based on their ability to perform would require a testing and research phase to ensure that it is effective. It is clear from multiple studies that the inclusion method was not successful in significantly increasing the performance of any students. Even more unfortunate is all of the evidence that suggests that teachers do not implement this practice, regardless of the fact that it is currently considered the most successful method. In order to adhere to the Individuals with Disabilities Act of 1990, it must be clearly determined and demonstrated that whatever method is being used by school systems is effectively providing the guaranteed education that is appropriate for all students (Kurtzig Freedman, 1). It must also be clearly reported and documented that whatever methods are decided to be most successful are actually being put into practice by all teachers of students with special needs. Inclusive methods should slowly be removed from teaching plans and curriculums and new methods of dividing students by ability should be put in place. The notion of a general education classroom should not exist in the future, because each student should be receiving an education that is appropriate for his or her abilities and skills.

Works Cited

Bricker, Diane. "The challenge of inclusion." Journal of Early Intervention 19.3 (1995): 179-194. Damore, Sharon J., and Christopher Murray. "Urban elementary school teachers' perspectives regarding collaborative teaching practices." Remedial and Special Education 30.4 (2009): 234-244. Foster, E. Michael, and Erin Pearson. "Is Inclusivity an Indicator of Quality of Care for Children With Autism in Special Education?." Pediatrics 130.Supplement 2 (2012): S179-S185. Goodman, Janet I., et al. "Inclusion and Graduation Rates: What Are the Outcomes?." Journal of Disability Policy Studies 21.4 (2011): 241-252. Kauffman, James M., et al. "Diverse Knowledge and Skills Require a Diversity of Instructional Groups A Position Statement." Remedial and Special Education 26.1 (2005): 2-6. Kurtzig Freedman, Miriam. "'Mainstreaming' Special-Ed Students Needs Debate." Wall Street Jouranl. N.p., 4 Aug. 2013. Web. Murphy, Donna M. "Implications of Inclusion for General and Special Education." The Elementary School Journal 96.5 (1996): 469-93.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Research Paper On Inclusion of Students With DisabilitiesDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Inclusion of Students With Disabilitiesc9rvcwhfPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethical Issues Surrounding Special Education Instructional Strategies 1Document7 pagesEthical Issues Surrounding Special Education Instructional Strategies 1api-315705429Pas encore d'évaluation

- CritiqueDocument4 pagesCritiqueShannon may torremochaPas encore d'évaluation

- Develop Your Understanding of Inclusive EducationDocument4 pagesDevelop Your Understanding of Inclusive EducationYing Ying TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Crowley A Inclusive Philosophy StatementDocument6 pagesCrowley A Inclusive Philosophy Statementapi-704137769Pas encore d'évaluation

- 04 26 2023 Revised ResearchDocument13 pages04 26 2023 Revised ResearchLloyd Amphrey TadeoPas encore d'évaluation

- Primary Teachers Viewpoints On Issues and Challenges Draft Pa Lang Hindi Pa Stress HeheheheDocument8 pagesPrimary Teachers Viewpoints On Issues and Challenges Draft Pa Lang Hindi Pa Stress HeheheheChristian MartinPas encore d'évaluation

- Classroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsD'EverandClassroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsPas encore d'évaluation

- InclusiveDocument4 pagesInclusiveapi-531838839Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Education - Definition, Examples, and Classroom Strategies - Resilient EducatorDocument5 pagesInclusive Education - Definition, Examples, and Classroom Strategies - Resilient EducatorChristina NaviaPas encore d'évaluation

- Educ 6327 Research Plan GeimerpmDocument15 pagesEduc 6327 Research Plan Geimerpmapi-301375841Pas encore d'évaluation

- Are We Ready For Inclusive EducationDocument3 pagesAre We Ready For Inclusive Educationkarl credoPas encore d'évaluation

- Changes in Preservice Teacher Attitudes Toward Inclusion: University of Nebraska-Omaha, Omaha, NE, USADocument8 pagesChanges in Preservice Teacher Attitudes Toward Inclusion: University of Nebraska-Omaha, Omaha, NE, USAEdot MokhtarPas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Education For Students With Disabilities - Assessment 1Document4 pagesInclusive Education For Students With Disabilities - Assessment 1api-357683310Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Education: What It Means, Proven Strategies, and A Case StudyDocument6 pagesInclusive Education: What It Means, Proven Strategies, and A Case StudyXerish DewanPas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusion Research PaperDocument12 pagesInclusion Research Paperstevendgreene85100% (3)

- Assignment 1 Essay-AprilDocument7 pagesAssignment 1 Essay-Aprilapi-519998613Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive EducationDocument2 pagesInclusive EducationTanvi PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- ACA Essay Jip Duijn FinalDocument4 pagesACA Essay Jip Duijn FinaljipduynPas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Disability Awareness Educational Programs On An InclusDocument32 pagesEffects of Disability Awareness Educational Programs On An Inclusjosue iturraldePas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsD'EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsPas encore d'évaluation

- swrk724 Final PaperDocument13 pagesswrk724 Final Paperapi-578092724Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Teaching Practices in Post-Secondary EducationDocument32 pagesInclusive Teaching Practices in Post-Secondary EducationinvocatlunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research .Proposal by Imran Ali SahajiDocument7 pagesResearch .Proposal by Imran Ali SahajiimranPas encore d'évaluation

- Alternate Assessment of Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: A Research ReportD'EverandAlternate Assessment of Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities: A Research ReportPas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusion PortfolioDocument20 pagesInclusion Portfolioapi-291611974Pas encore d'évaluation

- Iskrats 1111Document7 pagesIskrats 1111Jennifer Villadores YuPas encore d'évaluation

- Tash-Faqs About Inclusive EducationDocument3 pagesTash-Faqs About Inclusive Educationapi-309070428Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive 2h2018assessment1 EthansaisDocument8 pagesInclusive 2h2018assessment1 Ethansaisapi-357549157Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction: Teaching in Diverse, Standards-Based ClassroomsDocument12 pagesIntroduction: Teaching in Diverse, Standards-Based Classroomsjunjun gallosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Educational Organization & Management 2 (Updated)Document15 pagesEducational Organization & Management 2 (Updated)brightPas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive PedagogyDocument10 pagesInclusive PedagogyzainabPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 4 Final Rev21Document11 pagesGroup 4 Final Rev21api-164171522Pas encore d'évaluation

- Incomplete ResearchDocument12 pagesIncomplete ResearchHANNALEI NORIELPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 - Inclusive Education - Advocacy For Inclusion Position PaperDocument6 pages1 - Inclusive Education - Advocacy For Inclusion Position PaperIka Agreesya Oktaviandra100% (2)

- Title Research: The Impact of Mass Promotion On Student Literacy in Elementary SchoolDocument15 pagesTitle Research: The Impact of Mass Promotion On Student Literacy in Elementary SchoolBan ViolaPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Paper Educ 201Document8 pagesFinal Paper Educ 201api-445526818Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edu 690 Action Research Project ProposalDocument19 pagesEdu 690 Action Research Project Proposalapi-534676108Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparison of The TeacherDocument49 pagesA Comparison of The TeacherSteffiPas encore d'évaluation

- Edu Article ResponseDocument5 pagesEdu Article Responseapi-599615925Pas encore d'évaluation

- What The Research Says On Inclusive EducationDocument4 pagesWhat The Research Says On Inclusive EducationNasrun Abd ManafPas encore d'évaluation

- Research by Lyka CuteDocument4 pagesResearch by Lyka CuteChamphel Kyle DaipanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Importance and Necessity of Inclusive Education For Students With Special Educational NeedsDocument7 pagesThe Importance and Necessity of Inclusive Education For Students With Special Educational Needsapi-267872560Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 5 NotesDocument11 pagesLesson 5 NotesPrincess SamPas encore d'évaluation

- Action Research To Improve Teaching and LearningDocument9 pagesAction Research To Improve Teaching and LearningandyPas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusive Workforce Capability IssuesDocument3 pagesInclusive Workforce Capability Issuesapi-460570858Pas encore d'évaluation

- Essay: Adaptation of Lesson Plan Incorporating Universal Design For LearningDocument9 pagesEssay: Adaptation of Lesson Plan Incorporating Universal Design For Learningapi-429810354Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1.5 - Barriers To Inclusion Systemic Barriers, Societal Barriers and Pedagogical BarriersDocument7 pages1.5 - Barriers To Inclusion Systemic Barriers, Societal Barriers and Pedagogical BarriersAnum Iqbal100% (2)

- Benefits Collaborative TeachingDocument13 pagesBenefits Collaborative TeachingMaria Alona SacayananPas encore d'évaluation

- Teachers Attitudes Toward The Inclusion of Students With AutismDocument24 pagesTeachers Attitudes Toward The Inclusion of Students With Autismbig fourPas encore d'évaluation

- Las Mejores Prácticas de Inclusión en Educación BásicaDocument20 pagesLas Mejores Prácticas de Inclusión en Educación BásicasdanobeitiaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Attitude of Teachers On InclusionDocument12 pagesThe Attitude of Teachers On InclusionthenimadhavanPas encore d'évaluation

- Psy. EditedDocument11 pagesPsy. EditedDISHONPas encore d'évaluation

- Honey Marrie Learning Insights (Edu515) 6 Topics Discussed On October 1Document6 pagesHoney Marrie Learning Insights (Edu515) 6 Topics Discussed On October 1Honey MarriePas encore d'évaluation

- Group ProposalDocument23 pagesGroup Proposalapi-251294159Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sped CurriculumDocument11 pagesSped CurriculumKath Tan AlcantaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Inquiry Brief Final NewsletterDocument4 pagesInquiry Brief Final Newsletterapi-239787387Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment 2 - 22057601 - Abdul Munem Chowdhury 2Document8 pagesAssessment 2 - 22057601 - Abdul Munem Chowdhury 2munemPas encore d'évaluation

- ManuscriptDocument16 pagesManuscriptOLSH Capitol ParishPas encore d'évaluation

- Agbay Final 2Document35 pagesAgbay Final 2Lady Clyne LaidPas encore d'évaluation

- MCM Resume 9-5-2016Document4 pagesMCM Resume 9-5-2016api-355325987Pas encore d'évaluation

- Art Teacher Preparation For Teaching in An Inclusive Classroom - PDFDocument86 pagesArt Teacher Preparation For Teaching in An Inclusive Classroom - PDFLeighPas encore d'évaluation

- IEP and Lesson Plan Development HandbookDocument43 pagesIEP and Lesson Plan Development HandbookGan Zi XiPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1 Reuben Wahlang 18BArch10 PIDDocument4 pagesChapter 1 Reuben Wahlang 18BArch10 PIDReuben WahlangPas encore d'évaluation

- Probability of Corporal Punishment Lack of Resources and Vulnerable StudentsDocument12 pagesProbability of Corporal Punishment Lack of Resources and Vulnerable StudentsYasmine MustafaPas encore d'évaluation

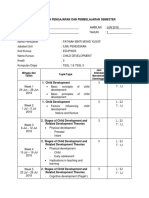

- RANCANGAN PENGAJARAN DAN PEMBELAJARAN SEMESTER StudentDocument4 pagesRANCANGAN PENGAJARAN DAN PEMBELAJARAN SEMESTER StudentThia SolvePas encore d'évaluation

- Conducting Pilot StudiesDocument0 pageConducting Pilot StudiesOana Sorina AndronicPas encore d'évaluation

- MKT 3401 Syllabus - Spring 2017Document3 pagesMKT 3401 Syllabus - Spring 2017Quinn TullPas encore d'évaluation

- Ctet EnglishDocument45 pagesCtet EnglishSoumya Pahuja0% (1)

- Ot1 Social Studies and Arts Lesson Two Assignments 1Document5 pagesOt1 Social Studies and Arts Lesson Two Assignments 1api-405595750Pas encore d'évaluation

- Levinson-Theorizing Educational Justice CIDEDocument17 pagesLevinson-Theorizing Educational Justice CIDELuis EchegollenPas encore d'évaluation

- HBEC4203 Assessment in Early Childhood EduDocument166 pagesHBEC4203 Assessment in Early Childhood EduKamil Iy100% (2)

- Haley MayerDocument3 pagesHaley MayerHaleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ritts - Research ProposalDocument20 pagesRitts - Research Proposalapi-618861143Pas encore d'évaluation

- Autism and Music EducationDocument12 pagesAutism and Music Educationallison_gerberPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Assignment TopicsDocument11 pagesThesis Assignment Topicsfhsn84Pas encore d'évaluation

- Module 1Document11 pagesModule 1Roliane LJ RugaPas encore d'évaluation

- Review What Was A Gap Is Now A ChasmDocument6 pagesReview What Was A Gap Is Now A Chasmiga setia utamiPas encore d'évaluation

- Prof Ed 1 MidtermDocument25 pagesProf Ed 1 MidtermRhey EragPas encore d'évaluation

- EYFSP Handbook 2019Document62 pagesEYFSP Handbook 2019Dwi Julya FatmasariPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Assistant DocumentsDocument83 pagesNursing Assistant Documentsapi-3718817Pas encore d'évaluation

- KHDA - Al Mawakeb School Al Garhoud 2015 2016 PDFDocument27 pagesKHDA - Al Mawakeb School Al Garhoud 2015 2016 PDFEdarabia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- Michigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityDocument52 pagesMichigan School Funding: Crisis and OpportunityThe Education Trust MidwestPas encore d'évaluation

- Program Planning enDocument44 pagesProgram Planning enCristine Joy Villajuan AndresPas encore d'évaluation

- Samantha Biskach STP Intermediate GroupDocument24 pagesSamantha Biskach STP Intermediate Groupapi-375963266Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ilp 2nd SemesterDocument7 pagesIlp 2nd Semesterapi-481796574Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dvhs Student Handbook 2018-2019Document42 pagesDvhs Student Handbook 2018-2019api-459764668Pas encore d'évaluation

- Effects of Complete Teaching Equipment and Facilities in The Student's Learning of Grade 10 - St. PaulDocument48 pagesEffects of Complete Teaching Equipment and Facilities in The Student's Learning of Grade 10 - St. PaulJoseph Jay BarreraPas encore d'évaluation

- TUELC Student Handbook: Taif UniversityDocument21 pagesTUELC Student Handbook: Taif UniversityMohammad AtiquePas encore d'évaluation

- Homeroom Guidance Form Grade 4 6Document23 pagesHomeroom Guidance Form Grade 4 6raff estradaPas encore d'évaluation