Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Jesus A Merkabah Mystic

Transféré par

markbruno195957%(7)57% ont trouvé ce document utile (7 votes)

2K vues25 pagesThe theory that Jesus was a Merkabah Mystic faces several difficulties. This article will review Chilton's description of Jesus' spirituality. It will also examine the evidence for Jesus' practice of heavenly ascent.

Description originale:

Titre original

Jesus a Merkabah Mystic

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThe theory that Jesus was a Merkabah Mystic faces several difficulties. This article will review Chilton's description of Jesus' spirituality. It will also examine the evidence for Jesus' practice of heavenly ascent.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

57%(7)57% ont trouvé ce document utile (7 votes)

2K vues25 pagesJesus A Merkabah Mystic

Transféré par

markbruno1959The theory that Jesus was a Merkabah Mystic faces several difficulties. This article will review Chilton's description of Jesus' spirituality. It will also examine the evidence for Jesus' practice of heavenly ascent.

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 25

Jesus as Merkabah Mystic

2003 by Charles L. Quarles

Introduction

According to Bruce Chilton in Rabbi Jesus, Jesus was a merkabah mystic who

mastered the technique of envisioning Gods chariot throne. He frequently enjoyed a

visionary ascent to the seventh heaven in which he beheld the divine glory and

participated in angelic praise of God by his practiced recitation of and meditation upon

the text of Ezekiel 1. For Chilton, this meditative practice explains the theophany that

accompanied Jesus baptism as well as many of Jesus so-called miracles including

healings, the stilling of the storm, and Jesus own spiritual resurrection.

The theory that Jesus was a merkabah mystic, however, faces several difficulties.

First, Chilton seems overconfident that the practice of the ascent was current during

Jesus lifetime. Second, the clues to which Chilton appeals in the Gospels as evidence of

Jesus mystical practice often involve idiosyncratic interpretations of the Gospels and of

ancient Jewish texts. This article will review Chiltons description of Jesus spirituality,

briefly explore the origins of merkabah mysticism, and examine the evidence for Jesus

practice of heavenly ascent.

A Brief Review of the Portrayal of Jesus Spirituality in Rabbi Jesus

Jesus journey toward Jewish mysticism began in his early youth when he visited

the temple with his mother soon after Joseph's death.

1

Jesus discovered that the presence

of his Abba was more palpable at the temple than any other place on earth.

2

He decided

1

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 23-32.

2

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 32.

2

that he could not return to his home in Nazareth and disappeared into the crowd hoping to

remain in the shadow of the temple where he felt included and accepted.

3

Jesus

temporarily lived as a street child in Jerusalem, begging for alms from merchants in the

Lower City.

4

At the height of winter, hunger and the cold drove Jesus to despair.

Rather than return to Nazareth in disgrace, he determined to seek out a renowned

rabbi named John the Baptist and to become John's talmid. This would allow him to

remain in Judea close to the temple and spare him from starvation.

5

John's teachings had

an esoteric side. John trained his young disciple in the practice of merkabah mysticism

which involved meditation on the divine chariot described in Ezekiel 1. John was a guru

who taught Jesus to alter his consciousness and enter the world of the chariot and the

Spirit.

6

As Jesus combined this meditation with repeated immersions for purification, he

came to have an increasingly vivid vision of the heavens splitting open and God's Spirit

descending on him in the form of a dove. He began to hear a divine voice affirming his

divine sonship. Jesus did not interpret his divine sonship in the metaphysical terms of the

creeds of the Christian church. Instead, Jesus saw himself as belonging to a long line of

visionaries who meditated on the chariot and were endowed with the Spirit.

7

When Jesus eventually returned to his home in Nazareth, many who encountered

him, including his own family members, feared that he was insane due to his obsession

3

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 32-34.

4

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 35.

5

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 41-50. In an interesting departure from Synoptic chronology, Chilton suggests that

Jesus was twelve and John was twenty-seven when they first met.

6

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 53.

7

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 50-58.

3

with meditative practice. This suspicion of insanity brought an end to the initially warm

welcome that the prodigal Jesus had enjoyed in Nazareth. Jesus confronted the elders in

Nazareth (Luke 4:16-30) and claimed to be the Lord's anointed, the bearer of Abba's

spirit. This was not a messianic claim but a claim that he was endowed with a prophetic

spirit so that God spoke to him through his meditation on the Chariot.

8

Jesus left Galilee and traveled to Jerusalem spurred on by his brothers' challenge

to "take his show to Jerusalem or to close it permanently" (John 7:3-4). This challenge

marked a transition in Jesus' life after which he sought to act as a chasid, a faith healer.

Jesus' first act as a chasid was the healing of the lame man at the pool of Bethesda in

which Jesus "was able to channel the energy of God" by drawing the crippled man into

his own meditation on the divine Throne. Chilton admits that no single explanation

accounts for shamanic power but implies that this particular miracle has a psychological

explanation.

9

After the healing of Simon's mother-in-law, Jesus' fame spread. Throngs of people

seeking healing or exorcism drove Jesus into wilderness solitude. In this solitude, Jesus

began using the Danielic vision of "one like a person" in his meditations. This "one like a

person" was an angelic personage who escorted Jesus closer to his Abba in the divine

court of heaven.

10

According the Chilton, Jesus' meditation on the chariot is the key to

understanding Jesus' response to the storm on the sea of Galilee. Jesus seemed to his

8

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 95-102.

9

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 103-11.

10

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 130-33.

4

disciples to be asleep during the dangerous storm when, in fact, his sleep was "a

meditation, a deep dreamlike trance." Jesus was so focused on the chariot that he was

oblivious to his surroundings. The disciples' belief that Jesus delivered them from the

storm "came mostly from the discipline of the Throne that he had mediated to them."

Thus the event "had more to do with the inner workings of Jesus' visionary practice than

with a miraculous event."

11

By 29 C.E. Jesus' visionary experiences were moving him in an unexpected

direction. Jesus' intimacy with the "one like a person" grew to the point that it bordered

on full identification. Jesus' demand that his disciples have the same kind of faith in him

that they had in his Abba is an expression of his identification with the Danielic son of

man.

12

Misunderstanding about the angelic center of Jesus' spirituality would eventually

lead to the doctrine of the Trinity.

On several occasions, Jesus appeared to resurrect the dead. Jesus was very adept

at recognizing the last vestiges of life in the nearly deceased. Jesus' disciples carefully

observed his actions and learned his kabbalah so that they would later perform similar

acts.

The transfiguration was a product of communal meditation by which Jesus drew

his disciples into his own visions so that they had a vivid experience of what Jesus saw

and heard in his meditation.

13

This contagious vision led to the sighting of Jesus on the

waters of Galilee. In Chilton's words, "The whole group was now functioning on an astral

11

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 154-57.

12

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 171-72.

13

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 190-195.

5

plane, flipping back and forth between the practical demands of piloting their craft and

the visionary conviction that their master would never abandon them."

14

The one like a person was Jesus' companion throughout the tortures that preceded

the crucifixion and during the crucifixion itself. This angelic personage beckoned Jesus to

his final transformation that climaxed his "progression from mamzer to talmid, to rabbi,

to messianic exorcist, to chasid, to prophet, and now to angel."

15

For Chilton, the

resurrection was "an angelic, nonmaterial event." Jesus' alleged post-resurrection

appearances were visionary experiences of the disciples who continued to practice Jesus'

kabbalah after his death.

16

Chilton explained:

Jesus' understanding was that human beings, in the course of their lives, could

shape their innermost breath--the pulse of their being as well as their cognitive

awareness of the Chariot--to correspond to the overpowering creativity of divine

Spirit. They became angelic, and that was the substance of their resurrection.

Jesus focuses us on the essence of our humanity, and allows us into his parallel

universe, imbued with the justice and glory of God.

17

Problems in Chiltons Portrayal of Jesus as Merkabah Mystic

Lack of a Consensus among Scholars regarding

the Origins of Merkabah Mysticism

Despite Chiltons confidence at this point, scholars have not yet demonstrated that

a developed merkabah mysticism that included the practice of the ascent existed during

the time of Christ. While some scholars suggest that the practice of the ascent originated

14

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 195.

15

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 281.

16

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 285. Chilton appealed to the Gospel According to the Hebrews to support this.

17

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 288.

6

in the first century of the common era or earlier, specialists in Jewish mysticism have not

yet reached a consensus on this.

Many scholars trace the origin of merkabah mysticism to the first century A.D. or

earlier though they qualify that the classical period of merkabah mysticism ran from the

fourth to sixth centuries. In most cases, this dating can be traced to dependency on the

works of Gershom Scholem (1897-1982), formerly Professor of Jewish Mysticism at

Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

18

Scholem identified merkabah mysticism as the first

phase of Jewish mysticism and suggested that this period extended from the first century

B.C. to the tenth A.D.

19

Scholem argued that the first text to use the terms maaseh

merkavah to refer to merkabah mysticism was Ben Sira 49:8, Ezekiel saw a vision, and

described the different orders of the chariot. Furthermore, b. Hagigah 13a told the story

of a child who was reading the book of Ezekiel at his teachers house when he came to

understand what the hashmal was. A fire immediately flashed from the hashmal and

consumed him. The Talmud traced the account to a source from the first century A.D., R.

Judah.

20

The evidence to which Scholem appealed to support the theory that the ascent

was practiced during the Second Temple period falls short of proving the theory. Neither

the reference in Sirach nor the tradition ascribed to Judah describe a voluntary practice of

ascent by contemporaries. While one observes increasing interest in the account of the

18

G. Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York: Shocken, 1941); idem, Jewish Gnosticism,

Merkabah Mysticism, and Talmudic Tradition (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America,

1960).

19

Scholem, Major Trends, 40.

20

G. Scholem, Merkabah Mysticism Encyclopedia Judaica 11:1386.

7

chariot or Maaseh Merkabah in the first century, it is unclear whether such fascination

had yet led to the mystical practices such as the ascent to the divine throne that

characterized true merkabah mysticism.

J.H. Laenen argues persuasively that while esoteric speculation on the chariot

may be traced to the end of the Second Temple period, these esoteric traditions

themselves may not be equated with true merkabah mysticism. Laenen dates the origin of

true merkabah mysticism to the second century of the common era. He states:

It was long assumed that one can speak of Jewish mysticism already in the

Second Temple period, from the second century BCE. Although some may still be

inclined to this view, many are now of the opinion that at this early stage it is not

a matter of real mystical activity in the sense of the ascent through the palaces to

the divine throne.

21

He also states:

The first tangible evidence of the existence of Jewish mysticism is not

found until the second century of the common era. The precise date of this

beginning is a matter of debate; estimates range from the second to the sixth

century.

22

He later adds:

At a certain stage, however, it seems that a transition took place to a new phase

which can indeed be called mysticism in the true sense. The question of how this

transition took place, from closed groups with their esoteric traditions to the

mystical activities of ascent through the heavenly palaces to Gods throne, cannot

be easily answered, since we have no knowledge of many of the relevant

historical details. Despite these objections it has been possible to arrive at a

feasible reconstruction of this change on the basis of other facts.

The early traditional literature from the time of the Tannaim, the rabbinic

teachers of the Mishnah, seems at one point to contain two new elements. First, an

entirely new approach is added to the traditional allegorical exegesis of the Song

of Songs, suggesting that God had given a description of himself in the Song.

21

J. H. Laenen, Jewish Mysticism: An Introduction (trans. David Orton; Louisville: Westminster John

Knox, 2001), 22.

22

Laenen, Jewish Mysticism, 18.

8

Second, esoteric speculation on the vision of the prophet Ezekiel, which contains

a description of the seven heavens, was inclined to develop into an active ascent

through the heavenly realms to the throne of glory. These changes seem to occur

in and around the school of R. Akiva, in the second century CE.

23

Given the lack of a consensus among scholars of Jewish mysticism regarding the

date of the origin of merkabah mysticism, Chiltons portrayal of Jesus as a merkabah

mystic must be regarded as tenuous. Chilton assumes that developed merkabah

mysticism that involved the practice of the ascent existed in the early first century but

offers no conclusive evidence to support this early existence.

Examination of Second Temple and Tannaitic Literature with

Possible Relationship to Merkabah Mysticism

Scholars who affirm that the practice of the ascent was current in the early first

century commonly refer to texts from the Pseudepigrapha, Philo, and the Dead Sea

Scrolls for support. Pre-Christian Pseudepigrapha refer to various Old Testament figures

who are caught up into heaven or ascend to heaven. 1 Enoch describes the ascent of

Enoch to heaven. However, the text offers no evidence of the practice of the ascent by the

author or his contemporaries since the narrative is based on speculation about Genesis

5:24. Testament of Levi 2-3, the text which most closely parallels the ascent of the

merkabah mystics, describes a dream of Levi in which he stepped from the top of a high

mountain into the heavens. The ascent of Levi is designed to portray Levis unique access

to Yahweh in support of the levitical priesthood which is given special honor in the

testaments of the other patriarchs. The theological motive behind the description of

Levis ascent best fulfills its purpose if the readers recognized Levis ascent as an event

23

Laenen, Jewish Mysticism, 26-27.

9

paralleled only by the ascent of other highly regarded biblical characters. The account

and others like it may be composed merely from the imagination of the author and with

an eye to the OT narratives. Though it is clear that Jews speculated about heavenly ascent

in the pre-Christian era, no evidence demonstrates that they actually sought to participate

in such an ascent.

J. M. Scott followed P. Borgen in suggesting that Philo of Alexandria practiced

the ascent. Both claimed that De Specialibus Legibus 3.1-2 was an autobiographical

account of Philos mystical practice.

24

Philo does refer to an experience in which I

appeared to be raised on high and borne aloft by a certain inspiration of the soul, and to

dwell in the regions of the sun and moon, and to associate with the whole heaven, and the

whole universal world. But close examination of the text within the broader context

shows that the language is purely figurative. Readers are not expected to take the

reference to ascent literally anymore than the following verse, which refers to Philo being

cast into a vast sea of public politics in which he struggles to stay afloat, should be read

literally.

Horton Smith has argued that 4Q491 is an autobiographical description of a

heavenly ascent.

25

Smiths interpretation of the Qumran document fail to persuade the

present researcher. However, even if his interpretation is correct, Smith acknowledges

24

J. M. Scott, Heavenly Ascent in Jewish and Pagan Traditions DNTB:449; P. Borgen, Heavenly Ascent

in Philo: An Examination of Selected Passages, in The Pseudepigrapha and Early Biblical Interpretation

(ed. J. J. Charlesworth and C. A. Evans; JSPSup 14; JSOT, 1993), 246-68.

25

Horton Smith, Two Ascended to HeavenJesus and the Author of 4Q491, in Jesus and the Dead Sea

Scrolls (ed. J. H. Charlesworth; ABRL; New York: Doubleday, 1992), 290-301.

10

that the claim of ascent could be completely false, a tale spun by an egomaniac.

26

Furthermore, the exalted being of 4Q491 claims none shall be exalted save me,

indicating that the exaltation was purely idiosyncratic and precluding theories that the

author represents a movement of mystics practicing the ascent.

The Angelic Liturgy of Qumran (particularly 4Q405 20 ii 21-22) contains ancient

speculation about this chariot throne:

The [cheru]bim prostrate themselves before him and bless. As they rise, a

whispered divine voice [is heard], and there is a roar of praise. When they drop

their wings, there is a [whispere]d divine voice. The cherubim bless the image of

the throne-chariot above the firmament, [and] they praise [the majes]ty of the

luminous firmament beneath his seat of glory. When the wheels advance, angels

of holiness come and go. From between his glorious wheels there is as it were a

fiery vision of most holy spirits. About them, the appearance of rivulets of fire in

the likeness of gleaming brass, and a work of . . . radiance in many-coloured

glory, marvelous pigments, clearly mingled. The spirits of the living "gods" move

perpetually with the glory of the marvellous chariot(s).

27

However, such texts do not confirm the existence of developed merkabah mysticism that

included the practice of the ascent. It is helpful to maintain Laenens distinction between

merkabah speculation and merkabah mysticism. Speculation about the appearance of the

chariot throne based on the descriptions of Ezekiel does not imply the mystical practice

of later merkabah mysticism. J. D. Tabor explained:

The fair number of Jewish (and Jewish-Christian) texts which make use

of the ascent to heaven as a means of legitimating rival claims of revelation and

authority is likely due to the polemics and party politics that characterized the

Second Temple period. It became a characteristic way, in the Hellenistic period,

of claiming archaic authority of the highest order, equal to a Enoch or Moses,

for ones vision of things.

28

26

Smith, Two Ascended, 300.

27

Geza Vermes, The Dead Sea Scrolls in English (3rd ed.; Sheffield: JSOT, 1987), 228.

28

James D. Tabor, Ascent to Heaven, ABD 3:92.

11

Furthermore, J. Laansma has pointed out that the Angelic Liturgy is significantly

different from the practices of the merkabah mystics since a) the experience described in

the Qumran literature is communal rather than individual b) the goal of the composition

is not the vision of the chariot throne but the description of the heavenly sacrificial

system and c) the document lacks reference to co-participation in the heavenly cult.

29

The earliest probable references to this mystical practice appear in the Mishnah.

M. Meg. 4:10 prohibits use of the chapter on the Chariot (Ezek. 1) in the public reading

from the Prophets in the context of synagogue worship. Other texts prohibited by this

mishnah were banned because of their explicit sexual content.

30

The rabbis wished to

avoid the moral dangers that might arise by focusing upon these texts. Since Ezekiel 1

lacks any sexual content, scholars have suspected that the rabbis hoped to avoid

promotion of the practice of the ascent which was so closely attached to this text. M.

Hag. 2:1 forbids a rabbi to expound the Chapter on the Chariot even before a single

student in fear that curiosity and speculation on the subject might harm him. This implies

that merkabah mysticism existed by the date of the final composition of the Mishnah (c.

29

Jon Laansma, Mysticism (DNTB; Downers Grove, Ill.: Intervarsity, 2000), 732.

30

R. Eliezer also excluded the chapter "Cause Jerusalem to Know" from the public reading (Ezek. 16:1ff)

apparently because of the sexual imagery used in this description of Jerusalems relationship with God and

idolatry. Some other passages were read but not publicly interpreted--Reuben's incest and adultery with

Jacob's concubine Bilhah (Gen. 35:22) and the second text on the golden calf that depicts Aaron as lying to

Moses (Ex. 32:21-35), blessing of the Priests from Num. 6:24-26, the story of David (2 Sam. 11:2-17)

[David's adultery and murder] and the story of Amnon (2 Sam. 13) [rape and incest].

12

AD 200) and that the practices associated with it were generally discouraged by the

rabbis.

31

The first clear reference to the mystical practice of voluntary ascent to heaven

appears in the Tosefta (c. A.D. 250). T. Hagigah 2.3-4 relates the entrance of four

rabbinic scholars into the garden and describes the consequences of the experience on

each. R. Akiba is said to have ascended and descended. This language, together with

the appeal to Song of Songs 1.4 which was an important text to later merkabah mystics,

has led many scholars to conclude that the Tosefta is referring to the ascent to the chariot

throne. Some scholars argue that it is improper to identify the garden (pardes) of this text

with the chariot throne of the merkabah mystics and thus date the practice of the ascent

later.

32

However, J. T. Milik published fragments of an Aramaic text from Qumran in

which the heavenly paradise of righteousness was called af?wq sdrp.

33

This suggests

31

Some scholars have argued that the prohibition regarding the account of the Chariot related only to

biblical-exegetical traditions and were unrelated at this time to the supposedly later practice of the heavenly

ascent. For this view, see Johann Maier, Vom Kultus zur Gnosis: Studien zur Vor- und Frhgeschichte der

Jdischen Gnosis (Salzburg: Mller, 1964), 128-46; Ephraim E. Urbach, lu twrwsmh <yanth

tpwqtb dwsh trwt, in idem, R. J. Zvi Werblowsky and C. Wirszubski, eds. Studies in Mysticism and

Religion Presented to Gershom G. Scholem on his Seventieth Birthday by Pupils, Colleagues and Friends

(Jerusalem: Magnes, 1967), 1-28; Peter Schfer, New Testament and Hekhalot Literature: The Journey

into Heaven in Paul and in Merkabah Mysticism, JJS 14 (1984): 19-35; David J. Halperin, The Merkabah

in Rabbinic Literature (AOS 62: New Haven, Conn.: American Oriental Society, 1980), 179-85; Joseph

Dan, The Ancient Jewish Mysticism (Tel-Aviv: MOD, 1993), 7-41; idem, Heart and Fountain, 15-23.

32

Laenen, Jewish Mysticism, 28

33

J. T. Milik, Hnoch au Pays des Aromates: ch. 27 32, Fragments Aramens de la Grotte 4 de

Qumran, Revue Biblique 65 (1958): 71 and 76. Scholem notes that 2 Cor. 12:2-4 constitutes another

13

that the garden mentioned in the Tosefta is heaven rather than a literal orchard.

Consequently, most scholars recognize this reference as the terminus ad quem for dating

the origin of a developed merkabah mysticism that involved the practice of the heavenly

ascent.

34

A saying attributed to R. Akiba in b. Hag. 14b indisputably refers to the ascent.

The text warns students not to confuse the pure marble stones with water since this would

prohibit entrance into Gods house. The importance of the ability of distinguishing

marble and water in order to gain access into the seventh heaven is a marked

characteristic of later hekhalot literature. Consequently, the reference demands that one

date the origin of merkabah mysticism before the final composition of the Babylonian

Talmud (A.D. 600).

The clearest description of the origin of merkabah mysticism in merkabah texts

points to the time just prior to the fall of Jerusalem (Hekalot Rabbati 13:1). Jewish

thought recognized an intrinsic connection between the authority for a practice and the

antiquity of that practice as is evidenced by the Tannaitic insistence that the oral law

could be traced to the Mosaic era. Therefore, one must suspect that, while a strong

parallel to this usage in Jewish Gnosticism, Merkabah Mysticism, and Talmudic Tradition (New York:

Jewish Theological Seminary, 1960), 17.

34

Some scholars suggest that the original form of the story contained no clear reference to merkabah

mysticism. For a discussion of this debate with recent bibliography, see James R. Davila, The Hodayot

Hymnist and the Four Who Entered Paradise, RevQ 17 (1996):457-78. B. M. Lewin shows that the debate

over the meaning of this text dates at least to the eleventh century in Otzar ha-Geonim: Thesaurus of the

Gaonic Responsa and Commentaries, vol. 4: Tractate Jom-Tow, Chagiga and Maschkin (Jerusalem:

Hebrew University, 1931), 13-15.

14

possibility exists that Jewish mystics would point to an excessively early date for the

origin of merkabah mysticism, they would probably not suggest a later than actual date.

Perhaps the strongest evidence for the practice of the ascent during the first

century appears in Colossians. Pauls descriptions of the Colossian error share many

correspondences with Jewish mysticism and particularly, with descriptions of the ascent

to the chariot throne.

35

In light of these parallels, several scholars have suggested that the

Colossian error was influenced by a form of Jewish mysticism with tendencies of the

later merkabah movement. Of the prevailing theories regarding the Colossian error, this

reconstruction seems to best satisfy the data of the epistle. However, many questions

regarding this possible influence still remain. Was the mysticism of the Colossian

errorists influenced by a phenomenon already in existence in Palestine or was the

mysticism a product of syncretism of Judaism and pagan mysticism already thriving in

Phrygia? Does the Colossian error of the early 60s necessitate existence of a similar

strictly Jewish phenomenon in Palestine over thirty years earlier?

36

Until these questions

can be answered, the data of Colossians will offer little help in understanding the

spirituality of Jesus of Nazareth.

The plausibility of Chiltons reconstruction of the life of Jesus which portrays him

as a merkabah mystic is weakened by both the historical data and the scholarly debates

35

A. J. Bandstra, Did the Colossian Errorists Need a Mediator? New Dimensions in New Testament Study

(eds. R. N. Longenecker and M. C. Tenney; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1974), 329-43; C. A. Evans, The

Colossian Mystics, Biblica 63 (1982): 188-205; F. O. Francis, Humility and Angelic Worship in Col.

2:18, Conflict at Colossae (ed. F. O. Francis and W. A. Meeks; 2

nd

ed.; SBLSBS 4; Missoula, MT:

Scholars Press, 1975), 163-95.

15

concerning the origin of the chariot ascent. If Chilton has uncovered new evidence about

the origin of this mystical practice of which the specialists in Jewish mysticism are

unaware, he should present this evidence and defend his conclusions. Otherwise,

Chiltons reconstruction of Jesus' life seems to rest on a rather shaky historical

foundation.

The Evidence for Jesus Mystical Practice in the Gospel Accounts

Chilton finds hints of Jesus mystical practice scattered throughout the Gospels.

First, Chilton claims that Mark 4:24 (which he translates, Look at what you listen to!)

expresses Jesus use of the rhythmical chant of the text of Ezekiel 1 with the cadence,

intonation and concentration necessary to envision the chariot throne. Thus the command

challenges the talmid to envision the heavenly scene that his chant describes . In order to

arrive at this interpretation, Chilton must read Mark 4:24 as an isolated logion bearing no

real connection to the surrounding context which refers to oral teaching without any

association with Ezekiel 1 or visionary experiences. Other scholars have recognized that

this immediate context is the best guide for a proper interpretation of the logion. C. S.

Mann states, "The significance of the Markan saying is very uncertain. From the context

it would appear to mean 'What attention you give to the teaching is also the measure of

the profit you will derive from it."

37

Joel Marcus states, "Mark, though, following in the

footsteps of some Qumran texts (e.g. 1QS 8:4; 1QH 14:18-19), reapplies the metaphor of

the measure to epistemology: people will receive insight according to the measure of

their attentiveness."

38

William Lane labeled all of Mark 4:21-25 as an Exhortation to

37

C. S. Mann, Mark (AB; vol 27; New York: Doubleday, 1986), 268.

38

Joel Marcus, Mark 1-8 (AB; vol. 27; New York: Doubleday, 1999), 320.

16

True Hearing and regarded the words take heed what you hear as the key to

interpreting the parable of the measure which constituted an appeal for spiritual

perception and appropriation of the word which Jesus proclaims.

39

Chilton's

interpretation is idiosyncratic and unsupported by the context in which it appears in

Mark's Gospel.

Chilton must also define blevpw in terms of a visionary experience, a meaning for

the verb which is unsubstantiated elsewhere in this gospel or in the New Testament. Mark

uses the word blevpw in warnings to Watch out or beware, (Mark 8:15; 12:38; 13:5,9),

in the sense Pay attention or Be alert (Mark 13:23,33), in reference to spiritual

insight (Mark 8:18), in reference to ordinary physical sight (Mark 4:12; 5:31; 8:23,24;

13:2), and as part of a Semitic idiom meaning to show favoritism (Mark 12:14).

Several linguistic features of Marks Gospel make Chiltons interpretation of Mark 4:24

particularly doubtful. First, Mark uses the verb in Mark 4:12 in a quotation of Isaiah 6:9-

10 (LXX) to refer to looking and not seeing in which blevpw refers to mere looking and

oJravw refers to true spiritual perception. Thus one would expect oJravw in a context that

39

William Lane, The Gospel of Mark (NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), 164, 167. Robert Guelich

noted that the construction blevpete tiv ajkouvete in Mark 4:24 is similar to the double imperative ajkouvete,

ijdouv that precedes the Parable of the Sower in 4:3 and both constructions emphasize the importance of the

parables to the evangelists audience. He suggested that these constructions, together with a similar

exhortation in Mark 7:3 constitute an introductory formula of exhortation. See Guelich, Mark 1-8:26 (WBC

34A; Dallas: Word, 1989), 232. For a more detailed discussion of the syntax and meaning of the blevpete

tiv ajkouvete construction, see R. T. France, The Gospel of Mark (NIGTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002),

210.

17

referred to an authentic vision of God that was hidden from all but a few.

40

Furthermore,

in Mark 13:33 blevpw is synonymous with ajgrupnevw which seems contrary to entrance

into the self-hypnotic sleep that Chilton equates with the ascent. The Lukan parallel,

blevpete ou\n pw'" ajkouvete (Luke 8:18), shows that the Evangelist did not understand

Jesus to be referring to attempts to envision what one was reciting. Luke evidently

believed that Jesus was commanding disciples to pay careful attention to the manner in

which they listened to his teaching. Finally, the verb blevpw normally means direct

ones attention to something, consider, note when followed by an indirect question (Mk.

4:24; Lk 8:18; 1 Cor. 3:10; Eph. 5:15).

41

Analysis of the grammar, vocabulary and

literary context of Mark 4:24 does not support a visionary interpretation of the command.

Second, Chilton believes that the divine manifestation that accompanied the

baptism of Jesus as recorded in the Synoptics (Mark 1:8; Matthew 3:11; Luke 3:16) was

actually a visionary experience that Jesus attained by altering his consciousness. Chilton

wrote:

Jesus repetitive, committed practice, his sometimes inadequate diet, and

his exposure to the elements contributed to the intensity of his vision of Gods

Chariot. Under Johns tutelage, he altered his consciousness and entered the world

of the Chariot and the Spirit. As he repeatedly immersed for purification, he came

to have an increasingly vivid vision of the heavens splitting open and Gods Spirit

descending upon him as a dove.

42

Chilton equates this experience with the "vision of God's chariot" sought by the

merkabah mystics. However, ancient records of the mystics' vision of the divine chariot

40

Interestingly, Paul uses the verb oJravw when referring to the apparent visionary experiences of the

Colossian errorists which so closely paralleled merkabah mysticism.

41

See Blevpw, BDAG 179.

42

Chilton, 55.

18

are quite different from the manifestation that the synoptic writers describe. The

Synoptics describe the heavens splitting open for this divine manifestation. Merkabah

mysticism saw the heavens as locked up tightly. The mystic could look upon God only if

he possessed certain spiritual and physical characteristics. He had to pass through each of

the seven heavens and the gate of each heaven could be entered only by knowledge of

secret passwords that would coerce the hostile angels who guarded each gate to permit

the mystic to enter.

43

The mystic had to pass other tests such as distinguishing marble

from water and those who failed such tests were overwhelmed with a rushing flood of

water or incinerated by heavenly fire.

44

Furthermore, merkabah mysticism focused not upon divine descent but upon

human ascent. Merkabah mystics taught that God was actually too great to reside in the

seventh heaven and that He daily descended to his heavenly throne from some realm

above. Attempting to coerce a divine descent to earth through mystical practices would

have likely been deemed strange, at best, and blasphemous, at worst, from the mystic's

perspective.

Finally, the merkabah mystics did not seek a vision of some symbolic

manifestation of Yahweh. Rather they sought to behold God in all of his splendor and

43

The passwords are called the nomina barbara. On the preparation for and requirements of the ascent, see

James R. Davila, Descenders to the Chariot: The People Behind the Hekhalot Literature (vol. 70 of

Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism; Boston: Brill, 2001), 93-125, 169-189;

44

On the dangers of the ascent, see Davila, Descenders, 136-155. For a thorough treatment of the test of

water in hekholot literature, see C. R. A. Morray-Jones, A Transparent Illusion: The Dangerous Vision of

Water in Hekhalot Mysticism. A Source-Critical and Tradition-Historical Inquiry (vol. 59 of Supplements

to the Journal for the Study of Judaism; Boston: Brill, 2002).

19

glory exalted upon his heavenly throne. Chilton recognized this inconsistency between

the baptismal theophany and the vision of the mystics and attempted to find a parallel in

Jewish literature in which a mystic sought a vision of God as dove. Chilton stated:

The bird that hovered over the face of the waters in Genesis 1:2 was

identified as a dove in the Rabbinic tradition of the Babylonian Talmud written in

the fifth century C.E. It speaks of a rabbi of the second century, Simon Ben Zoma,

who saw the holy spirit as a dove in the midst of the primeval waters in his vision

of the heavenly firmament during a trance (Chagigah 15a). Obviously, a direct

connection with the scene of Jesus' immersion in the Gospels can't be made on the

basis of such a late reference, but a fragment from Qumran that is undoubtedly

pre-Christian also attests the association of spirit and dove.

45

However, Chilton's appeal to the Talmud is weakened by several considerations.

The Babylonian Talmud does mention the Spirit brooding like a dove over the waters in

connection with the meditation of Ben Zoma on the creation account.

46

However, the

dove does not appear to be the focus of a mystical vision by Ben Zoma. Ben Zoma was

meditating upon the "works of creation" and was attempting to measure the distance

between the upper firmament and the lower firmament. He concluded on the basis of

midrashic exegesis, not a visionary experience, that the distance is less than a

handbreadth. He appealed to two texts, Genesis 1:2 and Deuteronomy 32:11-12, as

verification for his conclusion. The former passage refers to a divine "brooding" and the

later passage helped define the nature of that brooding. The Talmud seems to describe

45

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 297. Chilton appealed to Dale C. Allison, "The Baptist of Jesus and a New Dead

Sea Scroll," Biblical Archaeology Review 18.2 (1992) 58-60 to confirm the pre-Christian association of the

spirit and dove. Allison did not argue, however, that the reference to the dove portrayed Jesus as a

merkabah mystic who envisioned the brooding Spirit of the maaseh bereshit. He suggested that the dove

signaled that Jesus was the bringer of a new creation and that when Jesus came into the world, a new

age commenced and God, through his Holy Spirit, renewed his great work of creation.

46

b. Hag. 15a.

20

Ben Zomas exegetical labors rather than a trance. Furthermore, the Tosefta account of

Ben Zoma's meditation, which predates the Babylonian Talmud by approximately 250

years, makes no mention of a dove.

47

The Tosefta associates the creative brooding with

the brooding of the eagle which serves as a simile for God's care for his people in

Deuteronomy 32.

Chilton is probably correct that the heavenly vision of Jesus during the baptism is

to be understood against the backdrop of Genesis 1:2. However, the goal of the merkabah

mystics during the ascent was not a vision of a descending dove or even a vision of the

Spirit brooding over the primordial waters, but the glorious vision of Ezekiel 1.

48

The

coveted vision was that of the heavenly King enthroned in glory.

Chilton also claims that the statement "You are my beloved son" constitutes Jesus'

personal claim "that he is of the spiritual lineage of Israel's seers, the visionaries who

meditated on the Chariot and were blessed with the Spirit which pours out from the

Throne of the heavenly father."

49

However, Chilton offers no evidence that references to

merkabah mystics as "sons" are prominent in texts related to the ascent. Furthermore, the

47

For a good introduction to the Tosefta and Talmuds, see J. Neusner,

Rabbinic Literature: Mishnah and Tosefta, DNTB:893-97 and H. Maccoby, Rabbinic Literature:

Talmud, DNTB:897-902.

48

That is not to say that the descenders of the chariot were unconcerned about the creation account. The

creation account (Maaseh Bereshit) was one of the major foci of the mystics study. However, their

speculation concentrated upon questions of how God created the universe by 32 mysterious paths

consisting of the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet and the 10 sefirot. For a brief but helpful survey of

creation mysticism in ancient Judaism, see Dan and Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok, Jewish and Christian

Mysticism: An Introduction (New York: Continuum, 1994), 30-33.

21

scholarly consensus is that the divine utterance at Jesus' baptism alludes to Psalm 2:7

rather than esoteric texts.

50

A close comparison of the divine manifestation that occurred

at Jesus' baptism with the vision sought by the merkabah mystics demonstrates that the

two phenomena are far more different than similar. Chilton has failed to present

convincing evidence of a link between the baptismal theophany of the Synoptics and the

visionary experience of the descenders of the chariot.

Chilton also asserts that the charge that Jesus was mentally deranged confirms

Jesus' practice of the ascent:

The Gospels downplay this part of Jesus' activity. The term "deranged"

(existemi in Greek) strictly means "to be beside oneself," and corresponds to the

usage of michutz in the Talmid to describe the distracted state of a sage engrossed

in the Chariot (Chagigah 15a, in reference to Simon ben Zoma). Those around

Jesus feared that he was insane ("deranged") as a result of his obsession with

meditative practice.

51

However, the account of Ben Zoma's ascent in b. Hagigah 15a (y. Hagigah 77a-b)

does not unequivocally describe the trance by which one sought the ascent as "insanity."

The typical English translation of Joshua's statement to his disciples is "See, Ben Zoma is

outside." Both the translation of the Jerusalem Talmud and the Babylonian Talmud by

49

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 58.

50

Rudolph Schnackenburg, The Gospel of Matthew (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 35; W. D. Davies

and Dale C. Allison, Jr. Matthew I-VII (ICC; Edinburgh: T. and T. Clark, 1988), 338-39; Donald Hagner,

Matthew 1-13 (vol. 33A of WBC; Dallas: Word, 1993), 58-59.

51

Chilton, Rabbi Jesus, 95.

22

Jacob Neusner render the text in this fashion.

52

The older translation of the Babylonian

Talmud by I. Epstein also renders the Hebrew term "outside."

Epstein's translation notes that R. Hai Gaon interpreted the term as a reference to

insanity but that the Genesis Rabbah contained the reading "is gone."

53

If the

interpretation of Genesis Rabbah is correct, the word may be a reference to Ben Zomas

untimely death. The next line of the Tosefta adds, It was only a few days before Ben

Zoma died. The paragraph that follows the account in the Talmud seems to imply that

Ben Zoma's death was the consequence of his seeing the Chariot throne. The well-known

passage refers to four who entered paradise and warns of the disastrous effects that the

vision of the chariot had on all but one. Twice the account states that Ben Zoma cast a

look and died. This suggests that "outside" or "gone" may have been regarded by the final

editors of the Talmud as a reference to Ben Zoma's death. The Talmud comments on this

52

Jacob Neusner, trans., Hagigah and Moed Qatan (vol. 20 of Talmud of the Land of Israel: A

Preliminary Translation and Explanation; Chicago: University of Chicago, 1986), 44; Jacob Neuser, trans.,

Hagigah (vol. 12 of The Talmud of Babylonia: An American Translation; Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1993),

60.

53

I. Epstein, ed., Seder Mo'ed (vol. 4 of The Babylonian Talmud; London: Soncino Press, 1938), 92. The

Genesis Rabbah was probably redacted at approximately the same time as the Palestinian Talmud, probably

in the first half of the fifth century. See Moshe David Herr, Genesis Rabbah Encyclopedia Judaica

7:399-401; G. G. Porton, Rabbinic Literature: Midrashim, DNTB:892; and J. Neusner, Genesis Rabbah:

The Judaic Commentary to the Book of Genesis, A New American Translation (Atlanta: Scholars Press,

1985). R. Hai Gaon (Hai ben Sherira) was gaon of Pumbedita from 998-1038. His commentary on several

tractates of the Babylonian Talmud, several fragments of which have been preserved, postdates the Genesis

Rabbah by five hundred years. He was a mystic who personally practiced the ascent. See Jacob S.

Levinger, Hai ben Sherira, Encyclopedia Judaica 7:1130-32.

23

death with the words "Of him Scripture says: "Precious in the sight of the Lord is the

death of his saints" (Psa. 116:15). It appears that "sight of the Lord" was taken as

referring to Ben Zoma's vision of the Lord and that this vision was regarded as the cause

of his death. The Babylonian Talmud confirms this suspicion 2.1 IV.30 D states "Ben

Zoma peeked and was smitten, and of him Scripture says, "You have found honey? Eat

so much as is enough for you, lest you be filled up with it and vomit it out" (Prov.

25:16).

Jacob Neusners translation of the Tosefta text presents a more contextually

appropriate interpretation of the obscure reference to Ben Zoma being outside. He

translated the text: Said R. Joshua to his disciples: Ben Zoma is already on the outside

[among the sectarians].

54

In the preceding context of the Tosefta, Ben Zoma was deep in

thought concerning the works of creation. In particular, he attempted to discover the

distance between the upper waters and nether waters. He used midrashic technique to

interpret Genesis 1:2 in light of Deuteronomy 32:11-12 to argue that the distance

amounted only to a few inches. At this, R. Joshua replied that Ben Zoma was already

outside. Immediately after this scene, the Tosefta proceeds with a discussion of

Deuteronomy 4:32 which concluded that one should not seek to expound matters that

preceded Gods creation of humankind and argued in light of m. Hagigah 2:1 that those

who did so would be better off if they had not been born. This discussion clearly portrays

Ben Zomas exposition as heretical and thus clarifies the meaning of R. Joshuas

judgment that Ben Zoma was outside. Ben Zoma was outside of the parameters of

54

Jacob Neusner, trans., The Tosefta Translated from the Hebrew. Second Division: Moed (Atlanta:

Scholars, 1981), 313-14.

24

Jewish orthodoxy and to be recognized as a heretic. No compelling reason exists for

regarding the references to Ben Zoma in the Tosefta or Talmuds as parallel to the charge

of insanity against Jesus.

Chilton explained some of the apparent miracles of Jesus by appealing to his

ability to draw his disciples into his visionary experiences. However, descriptions of

corporate experiences of the ascent are lacking in the Hekhalot literature. R. Davila has

argued that the ascent did serve a corporate function. However, rather than the mystic

drawing disciples into his own ascent, he acted on behalf of the community in the ascent.

The representative function of the descender of the chariot is common in all forms of

shamanism in which the shaman functions as an intermediary in order to create a rapport

between this group and the supramundane world.

55

Chilton has failed to offer convincing evidence from the canonical Gospels to

support the hypothesis that Jesus was a merkabah mystic. Chilton might discover that

other sources, such as the Gospel of Thomas, provide more promising evidence of early

connections between Jesus teaching and merkabah mysticism.

56

However, evidence

suggests that the canonical Gospels are closer to the historical Jesus both chronologically

and theologically than the Gospel of Thomas and this must cast some doubt on a

reconstruction of Jesus life which depends exclusively or heavily on clues in Thomas.

57

55

See James R. Davila, The Hekhalot Literature and Shamanism, (SPSBL 33 1994), 767-89, esp. 784-86.

56

See the groundbreaking study of merkabah mysticism in Thomas, April D. De Conick, Seek to See Him:

Ascent and Vision Mysticism in the Gospel of Thomas (vol. 33 of Supplements to Vigilae Christianae;

Leiden: Brill, 1996).

57

C. A. Evans, Gospel of Thomas (DLNTD; Downers Grove, Ill.: Intervarsity, 1997), 1175-77; R. J.

Bauckham and S. E. Porter, Apocryphal Gospels (DNTB; Downers Grove, Ill.: Intervarsity, 2000), 72-

25

CONCLUSION

Chilton is to be commended for attempting to write a biography of Christ that

shows appreciation for Jesus identity as an authentic Jew in Palestine. Chilton also calls

attention to the importance of descriptions of Jesus as rabbi which are often overlooked

by contemporary scholars searching for categories for classifying Jesus actions and

teachings. However, Chiltons portrayal of Jesus as a merkabah mystic contributes little

to the quest for the historical Jesus. The portrayal depends upon the use of late sources

which may not accurately describe spiritual phenomena current in first-century Palestine.

Furthermore, the alleged parallels between Jesus spiritual practice and that of the later

merkabah mystics to which Chilton points fail to withstand close scrutiny. Although the

parallels initially appear to be convincing, careful comparison between the words and

activities of Jesus and those of the descenders of the chariot shows that the differences

are far more numerous than the similarities. Consequently, Chiltons biography of Rabbi

Jesus fails to establish the plausibility of his new explanations for the miracles of Jesus,

his self-designation as Son of Man, and the accounts of his resurrection.

74; C. L. Blomberg, Tradition and Redaction in the Parables of the Gospel of Thomas, in Gospel

Perspectives 5: The Jesus Tradition Outside of the Gospels, ed. D. Wenham (Sheffield: JSOT, 1984), 177-

205; C. A. Evans, Jesus in the Agrapha and Apocryphal Gospels in Studying the Historical Jesus:

Evaluations of the State of Current Research, ed. B. D. Chilton and C. A. Evans, (NTTS 19; Leiden: E. J. B

Brill, 1994), 499-502. See especially B. D. Chilton, The Gospel according to Thomas as a Source of

Jesus Teaching in Gospel Perspectives 5: The Jesus Tradition Outside the Gospels, ed. D. Wenham

(Sheffield: JSOT, 1984), 155-75.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Moses and Aaron: Civil and Ecclesiasticalsed by the Ancient HebrewsD'EverandMoses and Aaron: Civil and Ecclesiasticalsed by the Ancient HebrewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Yeshua and the Law Vs Paul the False Apostle: ...The Very False Apostle Yeshua Commended the Ephesians for Rejecting in Revelation 2:2D'EverandYeshua and the Law Vs Paul the False Apostle: ...The Very False Apostle Yeshua Commended the Ephesians for Rejecting in Revelation 2:2Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Mystical Jesus: Book 5 of the Mysteries of the Redemption SeriesD'EverandThe Mystical Jesus: Book 5 of the Mysteries of the Redemption SeriesPas encore d'évaluation

- Practicing Gnosis - Ritual, Theurgy and Liturgy - Essays in Honor of Birger A. PearsonDocument583 pagesPracticing Gnosis - Ritual, Theurgy and Liturgy - Essays in Honor of Birger A. PearsonFrancesco Tabarrini98% (48)

- Jesus and The Gnostic Gospels PDFDocument27 pagesJesus and The Gnostic Gospels PDFAnonymous VgSZiD36a100% (1)

- Jesus & His Gnostic School PDFDocument222 pagesJesus & His Gnostic School PDFfabianPas encore d'évaluation

- Philo AlexandriaDocument16 pagesPhilo AlexandriaRami Touqan100% (1)

- COPTIC GNOSTIC TEXTS FROM NAG HAMMADI LIBRARYDocument5 pagesCOPTIC GNOSTIC TEXTS FROM NAG HAMMADI LIBRARYmatias herreraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gnostic JesusDocument23 pagesThe Gnostic Jesuscompnets_2000@yahoo.caPas encore d'évaluation

- Guide To Merkabah Mysticism Part 2Document5 pagesGuide To Merkabah Mysticism Part 2michelez6Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gnostic Wedding Feast - The Holy Eucharist in Gnosticism PDFDocument7 pagesGnostic Wedding Feast - The Holy Eucharist in Gnosticism PDFMarcos MarcondesPas encore d'évaluation

- Lamsa BibleDocument10 pagesLamsa BibleWealthEntrepreneur100% (1)

- Jesus The King, Merkabah MysticismDocument18 pagesJesus The King, Merkabah MysticismDaniel MihalachiPas encore d'évaluation

- 1the Coptic Gnostic Library A Complete Edition of The Nag Ham PDFDocument968 pages1the Coptic Gnostic Library A Complete Edition of The Nag Ham PDFJose100% (8)

- (Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies, 62) Madeleine Scopello-The Gospel of Judas in Context_ Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Gospel of Judas, Paris, Sorbonne, October 27th-28thDocument421 pages(Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies, 62) Madeleine Scopello-The Gospel of Judas in Context_ Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Gospel of Judas, Paris, Sorbonne, October 27th-28thMina Fawzy100% (3)

- Seven Mysteries of Knowledge Qumran E So PDFDocument38 pagesSeven Mysteries of Knowledge Qumran E So PDFStone JusticePas encore d'évaluation

- Ma'Aseh Merkabah LiteratureDocument84 pagesMa'Aseh Merkabah Literaturegetulionetto100% (2)

- Bell On Hell - Times Magazine 1Document14 pagesBell On Hell - Times Magazine 1Luciana Rodrigues GhauriPas encore d'évaluation

- (NHMS 089) Erin Evans - The Book of Jeu and The Pistis Sophia As Handbooks To Eternity PDFDocument295 pages(NHMS 089) Erin Evans - The Book of Jeu and The Pistis Sophia As Handbooks To Eternity PDFEsotericist Maior100% (13)

- The Gnosis or Ancient Wisdom in The Christian Scriptures - William KingslandDocument230 pagesThe Gnosis or Ancient Wisdom in The Christian Scriptures - William Kingslandtjramsden100% (2)

- Esoteric Treatise Into Frankist InitiationDocument119 pagesEsoteric Treatise Into Frankist InitiationYaakov Bar IlahPas encore d'évaluation

- Adam KadmonDocument2 pagesAdam KadmonTony HermanPas encore d'évaluation

- CherubimDocument19 pagesCherubimProf.M.M.Ninan100% (6)

- Yeshua - The Unknown JesusDocument401 pagesYeshua - The Unknown Jesusbeisinge100% (5)

- Multiple Mortal ProbationsDocument75 pagesMultiple Mortal ProbationsLichtsuchePas encore d'évaluation

- Hekhalot RabbatiDocument46 pagesHekhalot Rabbatispolakiewie100% (4)

- The Enoch-MetatronTraditionDocument395 pagesThe Enoch-MetatronTraditionAnqa700100% (6)

- The Gnostic ScripturesDocument6 pagesThe Gnostic ScripturesArch NemissisPas encore d'évaluation

- (Supplements To The Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy) James Davila - Hekhalot Literature in Translation - Major Texts of Merkavah Mysticism-BRILL (2013)Document452 pages(Supplements To The Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy) James Davila - Hekhalot Literature in Translation - Major Texts of Merkavah Mysticism-BRILL (2013)Niki Spasov100% (3)

- MelchizedekDocument39 pagesMelchizedekProf.M.M.Ninan100% (13)

- 2 ChokmahDocument1 page2 ChokmahFrater FurnulibisPas encore d'évaluation

- Kabbalistic Diagram of Sefirot Attributed to David ben Yehudah he-Ḥ asidDocument24 pagesKabbalistic Diagram of Sefirot Attributed to David ben Yehudah he-Ḥ asidEs MardocheePas encore d'évaluation

- Guide Merkabah Mysticism Part 1Document5 pagesGuide Merkabah Mysticism Part 1michelez6100% (1)

- Cathar Initiation RitualsDocument97 pagesCathar Initiation RitualsManuel Fernando NunezPas encore d'évaluation

- Western Christians and The Hebrew Name of God, From The Beginnings To The Seventeenth CenturyDocument598 pagesWestern Christians and The Hebrew Name of God, From The Beginnings To The Seventeenth CenturyTatiany Nonato100% (5)

- G. R. S. Mead - The Hymn of The Robe of Glory (1908)Document108 pagesG. R. S. Mead - The Hymn of The Robe of Glory (1908)MarioaaaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Essene and Gnostic StudiesDocument4 pagesEssene and Gnostic StudiesAudrey Haschemeyer100% (1)

- Gospel of TruthDocument75 pagesGospel of TruthnatzucowPas encore d'évaluation

- The Study of Christian Cabala in EnglishDocument79 pagesThe Study of Christian Cabala in EnglishPredrag AndjelkovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Merkabah Vision Text of The Dead Sea ScrollsDocument3 pagesMerkabah Vision Text of The Dead Sea ScrollsAdim AresPas encore d'évaluation

- Charles Fillmore The Story of Jesus Soul Evolution 100 156Document57 pagesCharles Fillmore The Story of Jesus Soul Evolution 100 156Hético MarxPas encore d'évaluation

- The Nature of ElohimDocument10 pagesThe Nature of ElohimcdmaplePas encore d'évaluation

- African Origins of Essene-Therapeutae DR PDFDocument8 pagesAfrican Origins of Essene-Therapeutae DR PDFMarco Flavio Torres TelloPas encore d'évaluation

- Notes On The Zohar in EnglishDocument61 pagesNotes On The Zohar in EnglishMichael Gordan100% (1)

- Apocyphon of JohnDocument132 pagesApocyphon of JohnanagigPas encore d'évaluation

- 1the Coptic Gnostic Library A Complete Edition of The Nag Ham PDFDocument931 pages1the Coptic Gnostic Library A Complete Edition of The Nag Ham PDFJose100% (6)

- Elior - The Three Temples PDFDocument316 pagesElior - The Three Temples PDFrjbarryiv100% (5)

- On the Road with Jesus: Teaching and HealingD'EverandOn the Road with Jesus: Teaching and HealingÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- The Jesus Revolution: Learning from Christ's First FollowersD'EverandThe Jesus Revolution: Learning from Christ's First FollowersÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (4)

- 444 Surprising Quotes About Jesus: A Treasury of Inspiring Thoughts and Classic QuotationsD'Everand444 Surprising Quotes About Jesus: A Treasury of Inspiring Thoughts and Classic QuotationsÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (4)

- The Inspirited Life: A Conversation Between Jesus and NicodemusD'EverandThe Inspirited Life: A Conversation Between Jesus and NicodemusPas encore d'évaluation

- The Third Day: The Reality of the ResurrectionD'EverandThe Third Day: The Reality of the ResurrectionÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2)

- Center of Gravity ClausewitzDocument17 pagesCenter of Gravity Clausewitzmarkbruno1959Pas encore d'évaluation

- Metaphysics of PropertyDocument80 pagesMetaphysics of Propertymarkbruno1959Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesser Key of SolomonDocument50 pagesLesser Key of Solomonmarkbruno1959Pas encore d'évaluation

- Confessions of A Serial EntrepreneurDocument54 pagesConfessions of A Serial Entrepreneurmarkbruno1959Pas encore d'évaluation

- Its No SecretDocument105 pagesIts No Secretmarkbruno1959Pas encore d'évaluation

- US Navy Course NAVEDTRA 12012 - HarmonyDocument112 pagesUS Navy Course NAVEDTRA 12012 - HarmonyGeorges100% (2)

- Klasifikasi Jis Japan Industrial StandardDocument5 pagesKlasifikasi Jis Japan Industrial StandardakhooeznPas encore d'évaluation

- Panchanguli Devi Mantra To Forecast FutureDocument1 pagePanchanguli Devi Mantra To Forecast FutureHAREESHPas encore d'évaluation

- Modeling Business Processes at the Faculty of Organizational SciencesDocument52 pagesModeling Business Processes at the Faculty of Organizational ScienceskurtovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Oracle 11g Murali Naresh TechnologyDocument127 pagesOracle 11g Murali Naresh Technologysaket123india83% (12)

- LP2012Document4 pagesLP2012Anonymous PnznvixPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Governance RubricDocument2 pagesCorporate Governance RubricCelestia StevenPas encore d'évaluation

- Jesus Is AliveDocument3 pagesJesus Is AliveNatalie MulfordPas encore d'évaluation

- Lab 3 - Operations On SignalsDocument8 pagesLab 3 - Operations On Signalsziafat shehzadPas encore d'évaluation

- The Four Spiritual LawsDocument3 pagesThe Four Spiritual Lawsecrinen7377100% (2)

- 3 - The Mystery of The Seal of The Last Princes of Halic-Volinian Russia - Czi - GBDocument51 pages3 - The Mystery of The Seal of The Last Princes of Halic-Volinian Russia - Czi - GBAdam SzymskiPas encore d'évaluation

- Misia Landau - Narratives of Human EvolutionDocument8 pagesMisia Landau - Narratives of Human EvolutionCatalina SC100% (1)

- 4+ Years SCCM Administrator Seeking New OpportunitiesDocument4 pages4+ Years SCCM Administrator Seeking New OpportunitiesraamanPas encore d'évaluation

- LGUserCSTool LogDocument1 pageLGUserCSTool LogDávison IsmaelPas encore d'évaluation

- CholanDocument2 pagesCholanThevalozheny RamaluPas encore d'évaluation

- ShazaDocument2 pagesShazashzslmnPas encore d'évaluation

- Sunniyo Ki Aapasi Ladai Ka Ilaaj (Urdu)Document28 pagesSunniyo Ki Aapasi Ladai Ka Ilaaj (Urdu)Mustafawi PublishingPas encore d'évaluation

- Balkh and the Sasanians: Insights from Bactrian Economic DocumentsDocument21 pagesBalkh and the Sasanians: Insights from Bactrian Economic DocumentsDonna HallPas encore d'évaluation

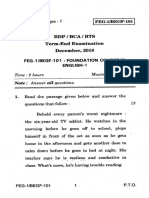

- Feg-1/Begf-101: Foundation Course in English-1Document6 pagesFeg-1/Begf-101: Foundation Course in English-1Riyance SethPas encore d'évaluation

- Susanne Pohl Resume 2019 No Contact InfoDocument1 pageSusanne Pohl Resume 2019 No Contact Infoapi-457874291Pas encore d'évaluation

- Primero de Secundaria INGLES 1 III BimestreDocument5 pagesPrimero de Secundaria INGLES 1 III BimestreTania Barreto PenadilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Dads 2Document15 pagesDads 2aymanmatrixone1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Embedded Interview Questions PDFDocument13 pagesEmbedded Interview Questions PDFViswanath NatarajPas encore d'évaluation

- KISI-KISI SOAL PENILAIAN AKHIR SEMESTER BAHASA INGGRIS KELAS XIDocument3 pagesKISI-KISI SOAL PENILAIAN AKHIR SEMESTER BAHASA INGGRIS KELAS XIekasusantyPas encore d'évaluation

- 8 English 1Document5 pages8 English 1Leonilo C. Dumaguing Jr.Pas encore d'évaluation

- 'Aesthetics Beyond Aesthetics' by Wolfgang WelschDocument17 pages'Aesthetics Beyond Aesthetics' by Wolfgang WelschFangLin HouPas encore d'évaluation

- Experimental Project On Action ResearchDocument3 pagesExperimental Project On Action Researchddum292Pas encore d'évaluation

- Quiapo, Manila: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument3 pagesQuiapo, Manila: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchRonaldPas encore d'évaluation

- Question Forms Auxiliary VerbsDocument10 pagesQuestion Forms Auxiliary VerbsMer-maidPas encore d'évaluation

- Vdocuments - MX - Autocad Vba Programming Tools and Techniques 562019e141df5Document433 pagesVdocuments - MX - Autocad Vba Programming Tools and Techniques 562019e141df5BENNANI MUSTAPHA1Pas encore d'évaluation