Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

674-Group3 - Mystery Motivator

Transféré par

api-259390419Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

674-Group3 - Mystery Motivator

Transféré par

api-259390419Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Mystery Motivator:

An Evidence-Based Intervention

Jackie Munroe, Kat Mrkva,

Shelina Hassanali & Amy Donovan

1) Mystery Motivator and School Psychology

2) Theoretical Basis

3) Description

4) Application

5) Tips for Implementation

6) Review of Research

7) Critical Thoughts

8) References

Overview

Mystery Motivator and School Psychology

Among greatest pd needs reported by teachers?

-Additional assistance with classroom

management and behaviour problems (highest

% requested this as number 1 in the K-5 levels)

(APA Coalition for Psychology in Schools and

Education, 2006)

-77% reported they could be teaching more effectively if

behaviour problems decreased (Public Agenda, 2004)

-Disruptive behaviours are critical barriers to academic

success of students (Kraemer et al., 2012)

- Teachers feel inadequately trained to deal with

disruptive behaviour of students and to address

behaviour challenges of mainstreamed special ed

students ( Chandler, 2000; as cited in Kowalewicz, 2012 )

-Classroom teachers often do not employ interventions

aimed at disruptive behaviour reduction, and feel unable

to appropriate implement them (Mottram et al., 2002)

Therefore...

-Need for evidence based (classroom target

group, or target student level) interventions

1. Relatively simple to implement yet effective

2. Proactively address student behaviours

3. Cost and time effective

4. Flexible, in terms of application to

different challenges

5. Target as needed: individual students,

groups, or classes

Kowalewicz, 2012

Mystery Motivator Description

-Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) in which appropriate

behaviour social/academic is defined, supported, rewarded

-MM intervention uses positive reinforcement (mystery

rewards) and mystery reinforcement schedules (variable

schedule) to decrease pre determined and defined

behavioural/academic problems and motivate appropriate

replacement behaviors

Kraemer, 2012; Rathvon, 2008

Kowalewicz, 2012

Mystery Motivator Description

-MM intervention is designed like a game that allows students to

potentially (intermittent) have immediate access to a mystery

reinforcer

To access the mystery reinforcer students must first

1) meet the specified criteria to engage in (homework

completion/homework accuracy) or refrain from (call outs, out of

seat) predetermined academic/social behaviours

2) colour in the current day on a MM calendar to reveal an invisible

M which may or may not be present on that day (variable schedule)

3) M appears: students have ? access

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6r5EhiHJQFE

Good video

describing MM

Theoretical Basis: Motivation

Students willingness, need, desire

and compulsion to participate in, and

be successful in the learning

process

(Bomia et al., 1997, p. 1 as cited in Brewster & Fager, 2000)

Motivation

Extrinsic Motivation:

Engagement in a task/activity

to attain a reward or avoid

punishment

Examples: stickers, candy,

prizes, taking away privilege

(recess)

Intrinsic Motivation:

Engagement in a task/activity

for its inherent satisfaction or

enjoyment of the task itself.

Example: play, reading

(Brewster & Fager, 2000; Dembo & Seli, 2012)

Motivation

Strive to increase intrinsic motivation to boost

students satisfaction, engagement and

persistence in school

Use extrinsic rewards sparingly

Give rewards when deserved

Outline clear expectation for behaviour/tasks

Verbal praise for work well done

Evaluate work and provide feedback soon

after work is completed

Focus on mastery learning

(Brewster & Fager, 2000; Dembo & Seli, 2012)

Theoretical Basis: Behavioural Factors

Group contingency (Litow & Pumroy, 1975; Gresham & Greshman 1982)

Dependent: group receives reinforcement based on performance

on one or select individuals

Independent: reinforce and individual for their performance

Interdependent: reinforce entire group for the groups performance

effective in decreasing disruptive behaviour

easy to manage, cost effective, efficient, avoids peer conflicts,

enhances cooperation in classroom

Variable schedule of reinforcement

Students are unaware of when reinforcement will be earned

because this varies by day

Builds reinforcement uncertainty- increasing anticipation of reward

Reduces satiation effects

Rathvon, 2008

Behavioural Factors

Immediate performance feedback

Increases desirable and decreases

undesirable behaviours

Positive Reinforcement

Desirable object or activity

Must have value

These reinforcers may be very

individual and can be difficult for

teachers to choose

May provide choice

Rathvon, 2008

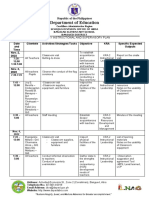

Steps Prior to MM Intervention

1.Interview with teacher to identify area/students needing to be targeted

2. Operationally define target/desired behaviour

3. Collect baseline data to record target behaviour frequency

4. Determine criteria for M success (example 50% of the current target

behaviour)

5. Create protocol to ensure appropriate intervention implementation

Kowalewicz, 2012

Description of Mystery Motivator Tools

Mystery Motivator Calendar

- Posterboard

chart displayed in class

divided

days of the

week boxes

Or...

-Rocket ship or

caterpillar

divided into sections

for days of week

Rathvon, 2008

-Using invisible ink record an M in 3-5 boxes at

random for each week (making the reward available

on those days only)

-Motivators should appear frequently at the onset of

intervention, and be gradually spread out

Added Incentive:

Bonus square:

record a number in

the bonus square

each week. If goals

were met for that

number of days in

that week,

distribute extra

reward!

Visual Display of Desired Behaviour

Behaviour stated and posted in

positive terms and represented

visually near MM calendar as

reminders

Mystery Motivator

Calendar

Mystery

Motivator

Calendar

Mystery Motivator Envelope

- Large manilla envelope with

- Index cards with descriptions of

different mystery prizes

- Displayed prominently in the class

- Concealing reinforcer increases

student anticipation

Mottrom et al., 2002

Tangible

Candy

Fruit Snacks

Pencil (fun)

Eraser (fun)

Stickers

Gum chewing day

Prize box access

Playdough time

Intangible

Pajama Day

Wacky Hair Day

Extra recess (15

minutes)

Movie with lunch

Free computer time

Free class time

Early release from

school (15 min to play

on playground)

Inside recess

-Students may mark

their reward

preference (or add

new rewards) on

reward menu

-Post classwide

menu when

intervention begins

(Rathvon, 2008)

-If student engages in opposite of desired

behaviour, a tally is recorded on the portable

tally counter

-At end of intervention

period choose student to colour

in the day of the week to reveal a (possible)

invisible M

-If M is revealed and students met pre

established criteria deliver reward from ?

MM envelope as soon as possible for

immediate reinforcement

(Kowalewicz, 2012)

Hand up to speak 20 per day

March 1-5, 2014 Ms. Ds class

Candy

Fruit Snacks

Pencil (fun)

Eraser (fun)

Stickers

Gum chewing day

Prize box access

Pajama Day

Wacky Hair Day

Extra recess (15

minutes)

Movie with lunch

Free computer time

Free class time

Application

Steps to application:

1. Introduce Mystery Motivator program to students (chance to earn rewards)

2. Review target behaviours

a. Demonstrate and model positive behaviours; also discuss behaviours to be avoided

3. Introduce the chart to students

a. Based on behaviour, students will have the chance to fill a blank on the chart to uncover a

possible reward (If they see the letter M appear, they get the mystery reward)

4. Review possible rewards (post a rewards menu)

5. Start the intervention

6. Monitor effectiveness by tracking any change in student behaviour

Application (contd)

What to do if no X appears?

Congratulate students on a job well done, clearly praising the exact behaviour(s) which were

demonstrated

Remind them that the next day may be a reward day

On days where the class does not meet the goal, review expectations and coach them toward

success the next day

Anticipation of a possible X the next day is often enough motivation to demonstrate the

desired behaviour

Application (contd)

Variations of Mystery Motivator

Mystery Motivator Bonus Square: At beginning of week, a number between 1-5 is written in invisible

ink on a bonus square. At end of week, students colour in bonus square. If they meet target behaviour

for number of days indicated on square, they get a bonus reward.

Team Mystery Motivator: Instead of the whole classroom, use the intervention with teams of students.

Each team gets their own calendar. If all students in the team demonstrate desired behaviour, they get

to colour in the square. If an X appears, each team member gets the reward.

Minimum Number of Xs: Assign a minimum number of Xs required to open the mystery motivator

envelope each month. This modification can be used as the intervention becomes effective, because

the monthly reward would (hopefully) be larger than any weekly reward and students would be

required to maintain behaviour over a longer period of time.

Implementation Tips

-Students accidentally colour in next days box:

establish clear expectations for what will happen if this occurs

-Students complain when the do not like M reward: clear expectations for what will

happen if this occurs

- Students intentionally throw the intervention: this student can become a team of 1

-Students begin to learn that after earning a reward one day, they will not earn a reward

the next day: always differ reward placements (sometimes back to back) so that

students cannot anticipate when rewards days will be, ensuring motivation remains high

https://www.sites.google.com/site/teachingnecessities/mystery-motivators

tips from teaching necessities

Review of the Research

Use of Mystery Motivator has been shown to be effective in improving a wide

range of behaviors:

Academic Performance (work completion/accuracy)

Disruptive/Off-task Behavior

Selective Mutism

Review of the Research

Disruptive Behavior

Murphy et al. examined the effects of

using Mystery Motivators to decrease

disruptive behavior among

preschoolers (Murphy et al., 2007)

They found that its use did reduce

disruptive behavior and therefore

increased learning time

Teachers rated it 4.5/5 on Teacher

Acceptability Questionnaire

Review of the Research

Disruptive Behavior

Kraemer et al. 2012 found the use of

Mystery Motivators decreased off-

task behavior in 5th grade students.

They suggest that Mystery Motivator can

be part of a Positive Behavior Support

System that can improve school culture

and strengthen pro-social behavior and

learning outcomes

Review of the Research

Disruptive Behavior

Schandling et al. hypothesized that use of Mystery Motivator would decrease

problem behavior for individual high school students (ages 14-17) as well as

the behavior of the class overall (Schandling et al., 2010)

Use of Mystery Motivator decreased problem behavior in teacher-identified students by 40%;

percentage of problem behavior exhibited by random peers decreased by 50%

Review of the Research

Work Completion

Madaus et al. utilized Mystery Motivators to improve homework completion in

grade 5 students (Madaus et al., 2003)

4 out of 5 participants demonstrated substantial improvement in homework completion.

Research by Theodore et al. supports the use of randomized interdependent

group contingency and reinforcers to improve homework completion and

accuracy in grade 4 students (Theodore et al., 2009)

Review of the Research

Selective Mutism

Studies by Kehle et al., (1998); & Kehle et al., (2012) looked at the use of self-

modeling in conjunction with mystery motivators in children with selective

mutism.

In the 6 year old, the child could converse freely following the second day of intervention; a 7

month follow-up showed the same results

In the 9 year old, the child could converse normally following 5 viewings of the video

Inside this envelope is the picture of a present that Jenny will receive when she asks for it in a tone of voice loud

enough for you to hear her ask for it (Kehle et al., 2012)

Mystery Motivator interventions account for the fact that attempting to establish interventions within the

classroom which are time consuming, rigid (follow strict guidelines for success), complicated in data

gathering, and administration, may not result in long term implementation

Mystery Motivator is efficient and easy to implement; readily adapted for use with

individuals or groups

Emerging data demonstrates efficacy in children with and without disabilities

(although further research is needed)

It can be used on its own or as part of an elaborate behavior support plan

Mystery Motivator has been deemed to be acceptable or satisfactory intervention by both teachers

and students

It increases childrens anticipation and interest

Critical Thoughts

Critical Thoughts

Social validity has been supported, in that teachers deem this intervention to be fair, appropriate and

effective within their classrooms (Moore et al, 1994; as cited in Kowalewicz, 2012)

Randomizing a reinforcer decreases the probability of reinforcer satiation, a common disadvantage of

many interdependent group contingencies (Little et al., 2010)

Random reinforcers decrease the possibility that students would deliberately ruin their

contingency program because they dislike the selected reinforcer.

Students are less likely to become disappointed and frustrated for not having earned a desirable

reinforcer

Mystery Motivator, like other group contingencies, can have the potential disadvantage of difficulties

that arise from the unequal contribution of group members toward the group goal (Little et al., 2010).

Mystery Motivator may seem too extensive if applied only to small groups or individual students, in

which case teacher preference must be taken into account (Shanding & Sterling, 2010)

References

Brewster, C. & Fager, J. (2000). Increasing student engagement and motivation: From time-on-task to homework. Northwest Regional Educational

Laboratory. Retrieved from http://educationnorthwest.org/webfm_send/452

Brief, E.B. I. Mystery Motivator (Avademic Intervention).

Coalition for Psychology in Schools and Education. (2006, August). Report on the Teacher Needs Survey. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological

Association, Center for Psychology in Schools and Education.

Dembo, M.H., & Seli, H. (2012). Motivation and learning strategies for college success: A focus on self-regulated learning. Routledge: Independence,

KY.

Gresham, F. N., & Gresham, G. N. (1982). Interdependent, Dependent, and Independent Group Contingencies for Controlling Disruptive Behavior.

Journal of Special Education, 16(1), 101-110. doi: 10.1177/002246698201600110

Kowalewicz, E. A. (2012). Mystery Motivator Calendar: An Interdependent Group Contingency, Variable Ratio, Classroom Intervention.

Kehle, T. J., Bray, M. A., Byeralcorace, G. F., Theodore, L. A., & Kovac, L. M. (2012). Augmented selfmodeling as an intervention for selective mutism.

Psychology in the Schools, 49(1), 93-103.

Kehle, T. J., Madaus, M. R., Baratta, V. S., & Bray, M. A. (1998). Augmented self-modeling as a treatment for children with selective mutism. Journal of

School Psychology, 36(3), 247-260.

Kraemer, E. E., Davies, S. C., Arndt, K. J., & Hunley, S. (2012). A comparison of the mystery motivator and the Get'Em On Task interventions for off

task behaviors. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 163-175.

Litow, L., & Pumroy, D.K. (1975). A brief review of classroom group-oriented contingencies. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis, 8 (3), 341347. doi:

10.1901/jaba.1975.8-341

LIttle, S. G., Akin-Little, A., & Newman-Eig, L..M. (2010). Effects on homework completeion and accuracy of varied and constant reinforcement within

interdependent group contingency system. Journal of Applied Psychology, 26(2), 115-131.

References

Madaus, M. M., Kehle, T. J., Madaus, J., & Bray, M. A. (2003). Mystery motivator as an intervention to promote homework completion and accuracy.

School Psychology International, 24(4), 369-377.

Mottram, A. M., Bray, M. A., Kehle, T. J., Broudy, M., & Jenson, W. R. (2002). A classroom-based intervention to reduce disruptive behaviors. Journal

of Applied School Psychology, 19(1), 65-74.

Murphy, K. A., Theodore, L. A., Aloiso, D., AlricEdwards, J. M., & Hughes, T. L. (2007). Interdependent group contingency and mystery motivators to

reduce preschool disruptive behavior. Psychology in the Schools, 44(1), 53-63.

Musser, E. H., Bray, M. A., Kehle, T. J., & Jenson, W. R. (2001). Reducing Disruptive Behaviors in Students with Serious Emotional Disturbance.

School Psychology Review, 30(2).

Mystery Motivator. (n.d.) Retrieved from Teaching Necessities:https://www.sites.google.com/site/teachingnecessities/mystery-motivators

Popkin, J., & Skinner, C. H. (2003). Enhancing academic performance in a classroom serving students with serious emotional disturbance:

Interdependent group contingencies with randomly selected components. School Psychology Review, 32(2), 282-295. Retrieved from: http:

//psycnet.apa.org.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/psycinfo/2003-99697-012

Public Agenda. (2004). Teaching interrupted: Do discipline policies in todays public

schools foster the common good? New York: Public Agenda.

Rathvon, N. (2008). Effective school interventions: Evidence-based strategies for improving student outcomes. Guilford Press.

Schanding Jr, G. T., & Sterling-Turner, H. E. (2010). Use of the mystery motivator for a high school class. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26(1),

38-53.

Skinner, C. H., Cashwell, C. S., & Dunn, M. S. (1996). Independent and interdependent group contingencies: Smoothing the rough waters. Special

Services in the Schools, 12(1-2), 61-78.

Wong, P. (2010). Selective mutism: a review of etiology, comorbidities, and treatment. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 7(3), 23.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- National University Lesson Plan Dec1 MDocument6 pagesNational University Lesson Plan Dec1 Mapi-320720255100% (1)

- Module 4 - Teaching StrategiesDocument22 pagesModule 4 - Teaching StrategiesSteven Paul SiawanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Blue-Print of ASSURE Instructional ModelsDocument3 pagesThe Blue-Print of ASSURE Instructional ModelsFery AshantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Dog Training BlueprintDocument46 pagesDog Training Blueprintoljavera67% (3)

- So2 Pre-Observation ReflectionDocument2 pagesSo2 Pre-Observation Reflectionapi-309758533Pas encore d'évaluation

- Stats and Probability Unit UbdDocument54 pagesStats and Probability Unit Ubdapi-314438906100% (1)

- 10 Innovative Formative Assessment Examples For TeDocument9 pages10 Innovative Formative Assessment Examples For TeNorie RosaryPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 9 LectureDocument89 pagesWeek 9 LecturesunnylamyatPas encore d'évaluation

- Abigail Smiles Observation 4 Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesAbigail Smiles Observation 4 Lesson Planapi-631485168Pas encore d'évaluation

- Point SheetsDocument11 pagesPoint Sheetsapi-287718398Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Test Review 2223Document10 pagesFinal Test Review 2223Damcio RamcioPas encore d'évaluation

- Formative Assessment Scenarios-ErkensDocument8 pagesFormative Assessment Scenarios-ErkensJolirose LapinigPas encore d'évaluation

- 10 Innovative Formative Assessment Examples For TeachersDocument5 pages10 Innovative Formative Assessment Examples For TeachersDiana ArianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Supervisor Observation 2Document7 pagesSupervisor Observation 2api-247305348Pas encore d'évaluation

- Slo Cycle Inquiry Project Template DraftDocument7 pagesSlo Cycle Inquiry Project Template Draftapi-301888952Pas encore d'évaluation

- ASSURE Model of Learning: Nalyze LearnersDocument4 pagesASSURE Model of Learning: Nalyze LearnersCesco ManzPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade 9 Gle Course OultlineDocument4 pagesGrade 9 Gle Course Oultlineapi-262322410Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rwilford Design Blueprint Medt7464Document5 pagesRwilford Design Blueprint Medt7464api-483892056Pas encore d'évaluation

- Math Lesson Plan 3 STDocument6 pagesMath Lesson Plan 3 STapi-606125340Pas encore d'évaluation

- Here Are Seven Effective Strategies For Teaching Elementary MathDocument13 pagesHere Are Seven Effective Strategies For Teaching Elementary MathAdonys Dela RosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 3Document6 pagesAssignment 3lai laiPas encore d'évaluation

- Answer SheetDocument4 pagesAnswer SheetBIG DUCKPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment PracticesDocument27 pagesAssessment PracticesKip PygmanPas encore d'évaluation

- IIED: ICT in Education Lesson Plan Form: Name of The LessonDocument4 pagesIIED: ICT in Education Lesson Plan Form: Name of The LessonTeachers Without Borders100% (1)

- 10 Strategies For Effectively Teaching Math To Elementary SchoolersDocument3 pages10 Strategies For Effectively Teaching Math To Elementary SchoolersRA CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- SOAR Full PlanDocument16 pagesSOAR Full PlanLaura WittPas encore d'évaluation

- Other Teaching Strategies and Supplementary Methods Math 7 10Document14 pagesOther Teaching Strategies and Supplementary Methods Math 7 10Nelmida, Henriane P.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elliott Ob3Document6 pagesElliott Ob3api-317782042Pas encore d'évaluation

- Activity 2 EGE 16 - Teaching Mathematics in Intermediate Grades Chapter 2. Number TheoryDocument3 pagesActivity 2 EGE 16 - Teaching Mathematics in Intermediate Grades Chapter 2. Number TheoryPrince Aira BellPas encore d'évaluation

- Positive ConsequencesDocument4 pagesPositive ConsequencesDiane RamentoPas encore d'évaluation

- Activities To Enhance Student Motivation and EngagementDocument58 pagesActivities To Enhance Student Motivation and EngagementLyza LancianPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Effective Teaching Strategies For The Classroom: F E B R U A R Y 2 3, 2 0 1 8Document26 pages7 Effective Teaching Strategies For The Classroom: F E B R U A R Y 2 3, 2 0 1 8julienne tadaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pep Assessment 2 TasksDocument3 pagesPep Assessment 2 TasksCatherinePas encore d'évaluation

- Marzanos Nine StrategiesDocument3 pagesMarzanos Nine Strategiesapi-283422107Pas encore d'évaluation

- Definition of InterventionDocument11 pagesDefinition of InterventionCristina TemajoPas encore d'évaluation

- Mathematics Inside The Black Box (Summary)Document5 pagesMathematics Inside The Black Box (Summary)Ishu Vohra100% (1)

- Authentic AssessmentDocument6 pagesAuthentic AssessmentirishtorillaPas encore d'évaluation

- Usp Observation KabootDocument5 pagesUsp Observation Kabootapi-320182378Pas encore d'évaluation

- Early Childhood Program Lesson Plan Format Movement Based ExperiencesDocument3 pagesEarly Childhood Program Lesson Plan Format Movement Based Experiencesapi-547766334Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Analyze LearnersDocument4 pagesA Analyze LearnersPrinceAndrePas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment PlansDocument3 pagesAssessment Plansmaylene martindalePas encore d'évaluation

- In This Issue: Attendance, Attendance, Attendance!Document5 pagesIn This Issue: Attendance, Attendance, Attendance!api-32442371Pas encore d'évaluation

- PriyaDocument12 pagesPriyaAnonymous rIHz6wD79tPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment and Evaluation in Social SciencesDocument5 pagesAssessment and Evaluation in Social Sciencesmatain elementary SchoolPas encore d'évaluation

- ARCS Model of Motivational DesignDocument7 pagesARCS Model of Motivational DesignRegine Natali FarralesPas encore d'évaluation

- Id ProjectDocument27 pagesId Projectapi-485411718Pas encore d'évaluation

- Maths 1 Assessment 2 Review and CritiqueDocument5 pagesMaths 1 Assessment 2 Review and CritiqueNishu JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Tpa 5Document14 pagesTpa 5api-634308335Pas encore d'évaluation

- Supervising Teacher Assessment of LessonDocument6 pagesSupervising Teacher Assessment of Lessonapi-250466497Pas encore d'évaluation

- Picture Talk: This Strategy CanDocument5 pagesPicture Talk: This Strategy CanJsyl Flor ReservaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre-Observation Information: D 1 - D P IDocument7 pagesPre-Observation Information: D 1 - D P Iapi-346507216Pas encore d'évaluation

- SrtlessonplanDocument3 pagesSrtlessonplanapi-469010904Pas encore d'évaluation

- Moreno FS2 Module CP7Document6 pagesMoreno FS2 Module CP7macmmorenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Prepare and Review For Factoring in AlgebraDocument4 pagesPrepare and Review For Factoring in AlgebraKayla Klein-WolfPas encore d'évaluation

- CT Obs 1Document3 pagesCT Obs 1api-284659663100% (1)

- Module of PSM Lesson PDFDocument15 pagesModule of PSM Lesson PDFGOCOTANO, CARYL A.Pas encore d'évaluation

- 06 Student Response Tools Lesson Idea Template 1Document3 pages06 Student Response Tools Lesson Idea Template 1api-412655448Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lessonplantemplate-Iste - Spring2014 Math LessonDocument4 pagesLessonplantemplate-Iste - Spring2014 Math Lessonapi-500426014Pas encore d'évaluation

- FS2-LearningEpisode-8 FINALDocument6 pagesFS2-LearningEpisode-8 FINALTrendy PorlagePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 8 Collaborative TeacherDocument15 pagesChapter 8 Collaborative TeacherbhoelscherPas encore d'évaluation

- Nemo Final Academic RecommendationsDocument2 pagesNemo Final Academic Recommendationsapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring The Impact of Religion On Childrens DevelopmentDocument25 pagesExploring The Impact of Religion On Childrens Developmentapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Almadina Charter Eval PresentationDocument14 pagesAlmadina Charter Eval Presentationapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wep New Brochure January 2013Document2 pagesWep New Brochure January 2013api-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Shelina Hassanali CVDocument5 pagesShelina Hassanali CVapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- SpedcodingcriteriaDocument14 pagesSpedcodingcriteriaapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cbe Proposal EditedDocument7 pagesCbe Proposal Editedapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- JapsycresultsDocument2 pagesJapsycresultsapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ethics Group Assignment Final PresentationDocument14 pagesEthics Group Assignment Final Presentationapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Stats Article Critique - HassanaliDocument9 pagesStats Article Critique - Hassanaliapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Karate Kid Final ReportDocument17 pagesKarate Kid Final Reportapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Psychostimulants PresentationDocument31 pagesPsychostimulants Presentationapi-2586826030% (1)

- Biker Boy Final ReportDocument22 pagesBiker Boy Final Reportapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Corporal Punishment PaperDocument18 pagesCorporal Punishment Paperapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hassanali 1Document7 pagesHassanali 1api-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Task 4 Hassanali Personal Position PaperDocument16 pagesLearning Task 4 Hassanali Personal Position Paperapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hassanali Article Review - Child Care ArrangementsDocument8 pagesHassanali Article Review - Child Care Arrangementsapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Paper - Ethics of Sharing Results With School When Parents Revoke ConsentDocument7 pagesFinal Paper - Ethics of Sharing Results With School When Parents Revoke Consentapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Stats Research PresDocument20 pagesStats Research Presapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Task 3 Theoretical Comparison PaperDocument11 pagesLearning Task 3 Theoretical Comparison Paperapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Paper - Sensory Processing in AutismDocument15 pagesPaper - Sensory Processing in Autismapi-258682603100% (1)

- Article Critique Paper Shelina HassanaliDocument8 pagesArticle Critique Paper Shelina Hassanaliapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hassanali2 - Short Paper2Document7 pagesHassanali2 - Short Paper2api-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mindup Vs Zones DebateDocument47 pagesMindup Vs Zones Debateapi-258682603100% (2)

- Learning Task 1 Basc-2 PresentationDocument17 pagesLearning Task 1 Basc-2 Presentationapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hassanalishelina 12 Nov 2012Document13 pagesHassanalishelina 12 Nov 2012api-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Williamjames Final Paper - Taylor and ShelinaDocument13 pagesWilliamjames Final Paper - Taylor and Shelinaapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hassanali Final Research ProposalDocument10 pagesHassanali Final Research Proposalapi-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anxietydisorders Finaleditoct16Document58 pagesAnxietydisorders Finaleditoct16api-258682603Pas encore d'évaluation

- Challenges 1, Module 2, Lesson 3Document2 pagesChallenges 1, Module 2, Lesson 3Dragana MilosevicPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Lesson Plan Year 3Document11 pagesReading Lesson Plan Year 3bibinahidaPas encore d'évaluation

- Name: - Date: - Grade & Section: - ScoreDocument5 pagesName: - Date: - Grade & Section: - ScoreCaryn Faith Bilagantol TeroPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is ParallelismDocument3 pagesWhat Is Parallelismcorsario97Pas encore d'évaluation

- Five-Step Lesson Plan Template: Objective. Connection To GoalDocument4 pagesFive-Step Lesson Plan Template: Objective. Connection To Goalapi-346733520Pas encore d'évaluation

- Direct Indirect SpeechDocument44 pagesDirect Indirect SpeechSalmanJamilPas encore d'évaluation

- FlyingHigh 3 TeacherBookDocument88 pagesFlyingHigh 3 TeacherBookEmilioCiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative AdjectivesDocument5 pagesComparative AdjectivesRik RoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing A Trauma-Informed Child Welfare SystemDocument9 pagesDeveloping A Trauma-Informed Child Welfare SystemKeii blackhoodPas encore d'évaluation

- Web-Page Recommendation Based On Web Usage and Domain KnowledgeDocument7 pagesWeb-Page Recommendation Based On Web Usage and Domain KnowledgeGR Techno SolutionsPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction of Expository TextDocument10 pagesIntroduction of Expository TextDaylani E ServicesPas encore d'évaluation

- Task 1 RNWDocument1 pageTask 1 RNWBeyaPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 C's of Effective Communication - Talentedge PDFDocument1 page7 C's of Effective Communication - Talentedge PDFEngr Abdul QadeerPas encore d'évaluation

- Design Thinking Whitepaper - AlgarytmDocument34 pagesDesign Thinking Whitepaper - AlgarytmRavi JastiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Generic Structures of Factual Report TextDocument4 pagesThe Generic Structures of Factual Report TextlanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 1 (Voc List) Grade 9Document2 pagesUnit 1 (Voc List) Grade 9Ahmad AminPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Listening)Document11 pagesTeaching Listening)sivaganesh_70% (1)

- Monthly Instructional and Supervisory PlanDocument6 pagesMonthly Instructional and Supervisory PlanTine CristinePas encore d'évaluation

- How To Correctly Use The Punctuation Marks in English - Handa Ka Funda - Online Coaching For CAT and Banking ExamsDocument6 pagesHow To Correctly Use The Punctuation Marks in English - Handa Ka Funda - Online Coaching For CAT and Banking ExamsSusmitaDuttaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mastering Word and ExcelDocument17 pagesMastering Word and ExceladrianoedwardjosephPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparative Analysis of Nike and Adidas Commercials: A Multimodal Approach To Building Brand StrategiesDocument67 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Nike and Adidas Commercials: A Multimodal Approach To Building Brand StrategiesPrince Leō KiñgPas encore d'évaluation

- Ai Term PaperDocument6 pagesAi Term Paperapi-339900601Pas encore d'évaluation

- Relationship ManagementDocument25 pagesRelationship ManagementcivodulPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 4 - Subordinate ClauseDocument5 pagesLesson 4 - Subordinate ClauseFie ZainPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 17: Planning For Laboratory and Industry-Based InstructionDocument34 pagesLesson 17: Planning For Laboratory and Industry-Based InstructionVARALAKSHMI SEERAPUPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Uses of The Simple Past TenseDocument3 pagesSpecial Uses of The Simple Past TenseUlil Albab0% (1)

- Gummy Bear Story RubricDocument1 pageGummy Bear Story Rubricapi-365008921Pas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Philosophy 1Document2 pagesTeaching Philosophy 1Hessa Mohammed100% (2)

- Nmba MK01Document19 pagesNmba MK01Ashutosh SinghPas encore d'évaluation