Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Biomimetic Architecture

Transféré par

stipsa592Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Biomimetic Architecture

Transféré par

stipsa592Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Biomimetic architecture

Biomimetic architecture is a contemporary philosophy

of architecture that seeks solutions for sustainability in

nature, not by replicating the natural forms, but by understanding the rules governing those forms. It is a multidisciplinary approach to sustainable design that follows a

set of principles rather than stylistic codes. It is part of a

larger movement known as biomimicry, which is the examination of nature, its models, systems, and processes

for the purpose of gaining inspiration in order to solve

man-made problems.

incorporated natural motifs into design such as the treeinspired columns. Late Antique and Byzantine arabesque

tendrils are stylized versions of the acanthus plant.[1]

Varros Aviary at Casinum from 64 BC reconstructed a

world in miniature.[2] A pond surrounded a domed structure at one end that held a variety of birds. A stone colonnaded portico had intermediate columns of living trees.

The Sagrada Famlia church by Antoni Gaudi begun in

1882 is a well-known example of using natures functional forms to answer a structural problem. He used

columns that modeled the branching canopies of trees to

solve statics problems in supporting the vault.[3]

History

Sagrada-familia-arches2

Organic architecture uses nature-inspired geometrical

forms in design and seeks to reconnect the human with his

or her surroundings. Kendrick Bangs Kellogg, a practicing organic architect, believes that above all, organic architecture should constantly remind us not to take Mother

Nature for granted work with her and allow her to guide

your life. Inhibit her, and humanity will be the loser.[4]

This falls in line with another guiding principle, which is

that form should follow ow and not work against the dynamic forces of nature.[5] Architect Daniel Liebermanns

commentary on organic architecture as a movement highlights the role of nature in building: a truer understanding of how we see, with our mind and eye, is the

foundation of everything organic. Mans eye and brain

evolved over aeons of time, most of which were within the

vast untrammeled and unpaved landscape of our Edenic

biosphere! We must go to Nature for our models now,

that is clear![4] Organic architects use man-made solutions with nature-inspired aesthetics to bring about an

awareness of the natural environment rather than relying

on natures solutions to answer mans problems.

Birdhouse at Casinum

Architecture has long drawn from nature as a source of

inspiration. Biomorphism, or the incorporation of natural

existing elements as inspiration in design, originated possibly with the beginning of man-made environments and

remains present today. The ancient Greeks and Romans

1

CHARACTERISTICS

Metabolist architecture, a movement present in Japan

post-WWII, stressed the idea of endless change in the biological world. Metabolists promoted exible architecture and dynamic cities that could meet the needs of a

changing urban environment.[6] The city is likened to a

human body in that its individual components are created and become obsolete, but the entity as a whole continues to develop. Like the individual cells of a human

body that grow and die although human body continues

to live, the city, too, is in a continuous cycle of growth

and change.[7] The methodology of Metabolists views nature as a metaphor for the man-made. Kisho Kurokawas

Helix City is modeled after DNA, but uses it as a strucBioniccar 11

tural metaphor rather than for its underlying qualities of

its purpose of genetic coding.

Biomimetic architecture goes beyond using nature as inspiration for the aesthetic components of built form, but

instead seeks to use nature to solve problems of the buildings functioning. Biomimicry means to imitate life and

originates from the Greek words bios (life) and mimesis (imitate). The movement is a branch o of the new

science dened and popularized by Janine Benyus in her

1997 book Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature

as one which studies nature and then imitates or takes inspiration from its designs and processes to solve human

problems.[8] Rather than thinking of the building as a machine for living in, biomimicry asks architects to think of Box Fish on Cobblers Reef

a building as a living thing for a living being.

Characteristics

constant intake of resources to function), and rely on solar energy instead of fossil fuels. The design approach

can either work from design to nature or from nature to

design. Design to nature means identifying a design problem and nding a parallel problem in nature for a solution.

An example of this is the DaimlerChrysler bionic car that

looked to the boxsh to build an aerodynamic body.[10]

The nature to design method is a solution-driven biologically inspired design. Designers start with a specic biological solution in mind and apply it to design. An example of this is Stos Lotusan paint, which is self-cleaning,

an idea presented by the lotus ower, which emerges clean

from swampy waters.[11]

Biomimetic architecture uses nature as a model, measure

and mentor to solve problems in architecture. It is not

the same as biomorphic architecture, which uses natural existing elements as sources of inspiration for aesthetic components of form. Instead, biomimetic architecture looks to nature as a model to imitate or take inspiration from natural designs and processes and applies

it to the man-made. It uses nature as a measure meaning

biomimicry uses an ecological standard to judge the eciency of human innovations. Nature as a mentor means

that biomimicry does not try to exploit nature by extracting material goods from it, but values nature as something 2.1

humans can learn from.[9]

Architectural innovations that are responsive to architecture do not have to resemble a plant or an animal. Where

form is intrinsic to an organisms function, then a building

modeled on a life forms processes may end up looking

like the organism too. Architecture can emulate natural

forms, functions and processes. Though a contemporary

concept in a technological age, biomimicry does not entail

the incorporation of complex technology in architecture.

In response to prior architectural movements biomimetic

architecture strives to move towards radical increases in

resource eciency, work in a closed loop model rather

than linear (work in a closed cycle that does not need a

Three Levels of Mimicry

Biomimicry can work on three levels: the organism, its

behaviors, and the ecosystem. Buildings on the organism level mimic a specic organism. Working on this

level alone without mimicking how the organism participates in a larger context may not be sucient to produce a building that integrates well with its environment

because an organism always functions and responds to a

larger context. On a behavior level, buildings mimic how

an organism behaves or relates to its larger context. On

the level of the ecosystem, a building mimics the natural

process and cycle of the greater environment. Ecosystem principles follow that ecosystems (1) are dependent

3.2

Behavior Level

on contemporary sunlight; (2) optimize the system rather

than its components; (3) are attuned to and dependent

on local conditions; (4) are diverse in components, relationships and information; (5) create conditions favorable to sustained life; and (6) adapt and evolve at dierent levels and at dierent rates.[12] Essentially, this means

that a number of components and processes make up an

ecosystem and they must work with each other rather than

against in order for the ecosystem to run smoothly. For

architectural design to mimic nature on the ecosystem

level it should follow these six principles.

3

3.1

Examples of Biomimicry in Architecture

Venus Flower Basket (sponge-labelled)

Organism Level

constructed of Ethylene Tetrauoroethylene (ETFE), a

material that is both light and strong.[14] The nal superOn the organism level, the architecture looks to the organ- structure weighs less than the air it contains.

ism itself, applying its form and/or functions to a building.

3.2 Behavior Level

On the behavior level, the building mimics how the organism interacts with its environment to build a structure

that can also t in without resistance in its surrounding

environment.

Termite mounds Namibia

Gherkin

Norman Fosters Gherkin Tower (2003) has a hexagonal

skin inspired by the Venus Flower Basket Sponge. This

sponge sits in an underwater environment with strong

water currents and its lattice-like exoskeleton and round

shape help disperse those stresses on the organism.[13]

The Eastgate Centre designed by architect Mick Pearce in

conjunction with engineers at Arup Associates is a large

oce and shopping complex in Harare, Zimbabwe. To

minimize potential costs of regulating the buildings inner

temperature Pearce looked to the self-cooling mounds of

African termites. The building has no air-conditioning or

heating but regulates its temperature with a passive cooling system inspired by the self-cooling mounds of African

termites.[15] The structure, however, does not have to look

like a termite mound to function like one and instead aesthetically draws from indigenous Zimbabwean masonry.

The Eden Project (2001) in Cornwall, England is a series of articial biomes with domes modeled after soap

bubbles and pollen grains. Grimshaw Architects looked

to nature to build an eective spherical shape. The re- The Qatar Cacti Building designed by Bangkok-based

sulting geodesic hexagonal bubbles inated with air were Aesthetics Architects for the Minister of Municipal Af-

5 SEE ALSO

Eastgate Centre, Harare, Zimbabwe

fairs and Agriculture is a projected building that uses the

cactuss relationship to its environment as a model for

building in the desert. The functional processes silently

at work are inspired by the way cacti sustain themselves

in a dry, scorching climate. Sun shades on the windows

open and close in response to heat, just as the cactus undergoes transpiration at night rather than during the day

to retain water.[16] The project reaches out to the ecosystem level in its adjoining botanical dome whose wastewater management system follows processes that conserve

water and has minimum waste outputs. Incorporating living organisms into the breakdown stage of the wastewater minimizes the amount of external energy resources

needed to fulll this task.[16] The dome would create a

climate and air controlled space that can be used for the

cultivation of a food source for employees.

3.3

Ecosystem Level

Building on the ecosystem level involves mimicking of

how the environments many components work together

and tends to be on the urban scale or a larger project with

multiple elements rather than a solitary structure.

The Cardboard to Caviar Project founded by Graham

Wiles in Wakeeld, UK is a cyclical closed-loop system

using waste as a nutrient.[17] The project pays restaurants

for their cardboard, shreds it, and sells it to equestrian

centers for horse bedding. Then the soiled bedding is

bought and put into a composting system, which produces

a lot of worms. The worms are fed to roe sh, which produce caviar, which is sold back to the restaurants. This

idea of waste for one as a nutrient for another has the potential to be translated to whole cities.[14]

the Namibian desert beetle to combat climate change in

an arid environment.[14] It draws upon the beetles ability to self-regulate its body temperature by accumulating

heat by day and to collect water droplets that form on its

wings. The greenhouse structure uses saltwater to provide evaporative cooling and humidication. The evaporated air condenses to fresh water allowing the greenhouse to remain heated at night. This system produces

more water than the interior plants need so the excess

is spewed out for the surrounding plants to grow. Solar

power plants work o of the idea that symbiotic relationships are important in nature, collecting sun while providing shade for plants to grow. The project is currently

in its pilot phase.

Lavasa, India is a proposed 8000-acre city by HOK (Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum) planned for a region of India subject to monsoon ooding.[19] The HOK team determined that the sites original ecosystem was a moist deciduous forest before it had become an arid landscape. In

response to the season ooding, they designed the building foundations to store water like the former trees did.

City rooftops mimic native the banyan g leaf looking to

its drip-tip system that allows water to run o while simultaneously cleaning its surface.[20] The strategy to move

excess water through channels is borrowed from local harvester ants, which use multi-path channels to divert water

away from their nests.

4 Criticisms

Biomimicry has been criticized for distancing man from

nature by dening the two terms as separate and distinct

from one another. The need to categorize human as distinct from nature upholds the traditional denition of nature, which is that it is those things or systems that come

into existence independently of human intention. Joe

Kaplinsky further argues that in basing itself on natures

design, biomimicry risks presuming the superiority of

nature-given solutions over the manmade.[21] In idolizing

natures systems and devaluing human design, biomimetic

structures cannot keep up with the man-made environment and its problems. He contends that evolution within

humanity is culturally based in technological innovations

rather than ecological evolution. However, architects and

engineers do not base their designs strictly o of nature

but only use parts of it as inspiration for architectural solutions. Since the nal product is actually a merging of

natural design with a human innovation, biomimicry can

actually be read as bringing man and nature in harmony

with one another.

The Sahara Forest Project designed by the rm

Exploration Architecture is a greenhouse that aims to rely

on solar energy alone to operate as a zero waste system.[18]

The project is on the ecosystem level because its many

components work together in a cyclical system. After

nding that the deserts used to be covered by forests, 5 See also

Exploration decided to intervene at the forest and desert

boundaries to reverse desertication. The project mimics HOK (Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum) Biomimicry

5.1

Further reading

Benyus, Janine. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired

by Nature. New York: Perennial, 2002.

Biomimicry 3.8 Institute, Biomimicry 3.8 Institute, http://biomimicry.net/about/biomimicry38/

institute/.[]

Pawlyn, Michael. Biomimicry in Architecture.

London: RIBA Publishing, 2011.

Vincent, Julian. Biomimetic Patterns in Architectural Design. Architectural Design 79, no. 6

(2009): 74-81.

References

[1] Alois Riegl, The Arabesque from Problems of style:

foundations for a history of ornament, translated by Evelyn Kain, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1992),

266-305.

[12] Salma Ashraf El Ahmar, Biomimicry as a Tool for Sustainable Architectural Design: Towards Morphogenetic

Architecture (masters thesis, Alexandria University,

2011), 22.

[13] Ehsaan, Lord Fosters Natural Inspiration: The Gherkin

Tower, biomimetic architecture (blog), March 24,

2010, http://www.biomimetic-architecture.com/2010/

lord-fosters-natural-inspiration-the-gherkin-tower/.

[14] Michael Pawlyn, Using natures genius in architecture (2011, February), [video le] Retrieved from

http://www.ted.com/talks/michael_pawlyn_using_

nature_s_genius_in_architecture.html?embed=true.

[15] Jill

Fehrenbacher,

Biomimetic

Architecture:

Green Building in Zimbabwe Modeled After Termite Mounds, Inhabitat,

last modied November 29, 2012, http://inhabitat.com/

building-modelled-on-termites-eastgate-centre-in-zimbabwe/.

[16] Bridgette Meinhold, Qatar Sprouts a Towering Cactus

Skyscraper, Inhabitat, last modied March 17, 2009,

http://inhabitat.com/qatar-cactus-office-building/.

[2] A. W. van Buren and R. M. Kennedy, Varros Aviary at

Casinum, The Journal of Roman Studies 9 (1919): 63.

[17] Michael Pawlyn, Biomimicry, in Green Design: From

Theory to Practice, edited by Ken Yeang and Arthur Spector, (London: Black Dog, 2011), 37.

[3] George R. Collins, Antonio Gaudi: Structure and Form,

Perspecta 8 (1963): 89.

[18] Sahara Forest Project, Sahara Forest Project, Inc, http:

//saharaforestproject.com.

[4] David Pearson, New Organic Architecture: the breaking

wave (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001),

10.

[19] Lavasa is Indias planned hill city, Lavasa Corporation

Ltd, http://www.lavasa.com.

[5] David Pearson, New Organic Architecture: the breaking

wave (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001),

14.

[6] Raaele Pernice, Metabolism Reconsidered: Its Role in

the Architectural Context of the World, Journal of Asian

Architecture and Building Engineering 3, no. 2 (2004),

359.

[7] Kenzo Tange, A Plan for Tokyo, 1960: Toward a

Structural Reorganization, in Architecture Culture 19431968: A Documentary Anthology, ed. Joan Ockman,

325-334 (New York: Rizzoli, 1993), 327.

[20] John

Gendall,

Architecture

That

Imitates

Life, Harvard Magazine, last modied October

2009,

http://harvardmagazine.com/2009/09/

architecture-imitates-life.

[21] Joe Kaplinsky, Biomimicry versus humanism, Architectural Design 76, (2006), 68.

7 External links

Michael Pawlyn: Using natures genius in architecture

@TED.com

[8] Janine Benyus, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. (New York: Perennial, 2002).

[9] Janine Benyus, Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature (New York: Perennial, 2002), 2.

[10] The Mercedes-Benz bionic car:

Streamlined

and light, like a sh in water - economical

and environmentally friendly thanks to the latest diesel technology, Daimler, last modied

June 7, 2005, http://media.daimler.com/dcmedia/

0-921-885913-1-815003-1-0-1-815031-0-1-11702-0-0-1-0-0-0-0-0.

html.

[11] StoColor Lotusan Lotus-Eect faade paint, Sto

http://www.sto.co.uk/25779_EN-Facade_

Ltd.,

paints-StoColor_Lotusan.htm.

8 TEXT AND IMAGE SOURCES, CONTRIBUTORS, AND LICENSES

Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses

8.1

Text

Biomimetic architecture Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biomimetic%20architecture?oldid=620407859 Contributors: Bearcat,

ELApro, Joe Decker, Malcolma, Vanjagenije, LionMans Account, Niceguyedc, Dthomsen8, Citation bot, Vanamonde93, Beebiene and

Anonymous: 2

8.2

Images

File:Bioniccar_11.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/42/Bioniccar_11.jpg License: CC-BY-SA-3.0 Contributors: Own work Original artist: NatiSythen

File:Birdhouse_at_Casinum.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e8/Birdhouse_at_Casinum.jpg License:

Public domain Contributors: Varro on Farming Original artist: Unknown

File:Box_Fish_on_Cobblers_Reef.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3c/Box_Fish_on_Cobblers_Reef.

jpg License: CC-BY-SA-3.0 Contributors: Own work Original artist: Johnmartindavies

File:Eastgate_Centre,_Harare,_Zimbabwe.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1e/Eastgate_Centre%2C_

Harare%2C_Zimbabwe.jpg License: CC-BY-SA-3.0 Contributors: Wikipedia:Contact us/Photo submission Original artist: David Brazier

File:Gherkin.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cf/Gherkin.jpg License: CC-BY-2.0 Contributors: Flickr

Original artist: Andy Wright from Sheeld, UK

File:Sagrada-familia-arches2.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ea/Sagrada-familia-arches2.jpg License:

CC-BY-3.0 Contributors: Own work Original artist: Rp22

File:Termite_mounds_namibia.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/25/Termite_mounds_namibia.jpg License: CC-BY-2.0 Contributors: IMG_1135 Original artist: Lothar Herzog from Kassel, Germany

File:Venus_Flower_Basket_(sponge-labelled).JPG Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/82/Venus_Flower_

Basket_%28sponge-labelled%29.JPG License: CC-BY-2.5 Contributors: My modication of image Venus_Flower_Basket.jpg contributed

by user:Grd Original artist: Myself, as modication of above

File:Wiki_letter_w.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/6/6c/Wiki_letter_w.svg License: Cc-by-sa-3.0 Contributors: ?

Original artist: ?

8.3

Content license

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Biomimetic ArchitectureDocument6 pagesBiomimetic ArchitectureNyx SolivenPas encore d'évaluation

- The Integration of Contemporary Architecture in Heritage SitesD'EverandThe Integration of Contemporary Architecture in Heritage SitesPas encore d'évaluation

- Organic ArchitectureDocument6 pagesOrganic ArchitecturePegah SoleimaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Organic Architecture 2Document8 pagesOrganic Architecture 2Nicolo GecoleaPas encore d'évaluation

- Peter Pearce - Structure in Nature Is Strategy For Design-MIT Press (1978)Document262 pagesPeter Pearce - Structure in Nature Is Strategy For Design-MIT Press (1978)isbro1788Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kiasma Museum of Contemporary ArtDocument17 pagesKiasma Museum of Contemporary ArtrodrigoguabaPas encore d'évaluation

- Natural Energy in Vernacular Architectur PDFDocument19 pagesNatural Energy in Vernacular Architectur PDFIñigo López VeristainPas encore d'évaluation

- Carlo ScarpaDocument10 pagesCarlo ScarpaNeitherboth75% (4)

- The Geometry of Organic ArchitectureDocument8 pagesThe Geometry of Organic Architecturewjzabala100% (1)

- Storytelling Through ArchitectureDocument67 pagesStorytelling Through ArchitectureArchiesivan22Pas encore d'évaluation

- Biomimicry in ArchitectureDocument11 pagesBiomimicry in ArchitectureJhon.Q56% (9)

- Teaching and Experimenting With Architectural Design PDFDocument497 pagesTeaching and Experimenting With Architectural Design PDFMaria Turcu100% (1)

- Architecture and Unconventional Computing Conference-Rachel Armstrong Martin Hanczyc and Neil SpillerDocument54 pagesArchitecture and Unconventional Computing Conference-Rachel Armstrong Martin Hanczyc and Neil SpillerPaolo AlborghettiPas encore d'évaluation

- Moussavi Kubo Function of Ornament1Document7 pagesMoussavi Kubo Function of Ornament1Daitsu NagasakiPas encore d'évaluation

- G3 - Spirit of ArchitectureDocument27 pagesG3 - Spirit of ArchitectureTanvi DhankharPas encore d'évaluation

- Daylight Architecture Magazine - 2008 Autumn 2Document37 pagesDaylight Architecture Magazine - 2008 Autumn 2Narvaez SandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Tadao Ando: Japanese Architect Known for Concrete MinimalismDocument4 pagesTadao Ando: Japanese Architect Known for Concrete Minimalismlongho2kPas encore d'évaluation

- Louis Kahn: The Space of Ideas: 23 October 2012 - by William JR CurtisDocument17 pagesLouis Kahn: The Space of Ideas: 23 October 2012 - by William JR CurtisRahnuma Ahmad TahitiPas encore d'évaluation

- Nostalgia in ArchitectureDocument13 pagesNostalgia in ArchitectureAfiya RaisaPas encore d'évaluation

- PDF Todd Gannon Zaha Hadid Zaha Hadid BMW Central Building CompressDocument160 pagesPDF Todd Gannon Zaha Hadid Zaha Hadid BMW Central Building CompressAakash Dharshan100% (1)

- Diagrams in ArchitectureDocument16 pagesDiagrams in ArchitectureAr Kethees WaranPas encore d'évaluation

- Architectural Facades in The 21st CenturyDocument154 pagesArchitectural Facades in The 21st CenturyBuse AslanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bioclimatic Architecture and CyprusDocument286 pagesBioclimatic Architecture and CyprusPetros LapithisPas encore d'évaluation

- New Architecture in Wood Forms and StructuresDocument184 pagesNew Architecture in Wood Forms and StructuresVictor Calixto100% (1)

- Tadao Ando PRSNTNDocument47 pagesTadao Ando PRSNTNShama Khan100% (3)

- Architectural Principles in The Age of CyberneticsDocument29 pagesArchitectural Principles in The Age of CyberneticsJosef Bolz100% (1)

- Pritzker Prize Architect AssignmentDocument56 pagesPritzker Prize Architect AssignmentShervin Peji100% (1)

- Félix Candela Builder of DreamsDocument24 pagesFélix Candela Builder of Dreamsfausto giovannardi100% (2)

- Postmortem Architecture - The Taste of Derrida by Mark WigleyDocument18 pagesPostmortem Architecture - The Taste of Derrida by Mark WigleyryansimonsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence AllowayDocument1 pageThe Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence Allowaymacarena vPas encore d'évaluation

- Temporary Housing Kobe EarthquakeDocument18 pagesTemporary Housing Kobe EarthquakeMeenu100% (1)

- Vasconcelos Library Alberto KalachDocument1 pageVasconcelos Library Alberto KalachDiana Andreea BadraganPas encore d'évaluation

- Mapping ResourcesDocument14 pagesMapping Resourcesdm2digitalmediaPas encore d'évaluation

- Studio Bow-Wow ETHZ Window Behaviorology KanazawaDocument1 pageStudio Bow-Wow ETHZ Window Behaviorology KanazawaV_KanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 14 - Biomimentic Design Strategies in Lightweight Structures of Achim Menges PDFDocument29 pagesGroup 14 - Biomimentic Design Strategies in Lightweight Structures of Achim Menges PDFtintintinaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reyner Banham and Rem Koolhaas, Critical ThinkingDocument4 pagesReyner Banham and Rem Koolhaas, Critical ThinkingAsa DarmatriajiPas encore d'évaluation

- Arata Isozaki: Presented By: Aarti Saxena B. Arch 4Document23 pagesArata Isozaki: Presented By: Aarti Saxena B. Arch 4Tariq NabeelPas encore d'évaluation

- Parasitic ArchitectureDocument4 pagesParasitic ArchitecturehopePas encore d'évaluation

- Eve Blau Comments On SANAA 2010 EssayDocument7 pagesEve Blau Comments On SANAA 2010 EssayIlaria BernardiPas encore d'évaluation

- ECOLOGICAL DESIGN: Architecture Between Design and EnvironmentDocument18 pagesECOLOGICAL DESIGN: Architecture Between Design and EnvironmentBrunirri Gerardo Paps Campos GaleazziPas encore d'évaluation

- Bionic ArchitectureDocument5 pagesBionic ArchitectureMaria Mariadesu0% (1)

- Green BuildingsDocument10 pagesGreen Buildingsromandi_s9744Pas encore d'évaluation

- Architecture and Philosophy PDFDocument227 pagesArchitecture and Philosophy PDFTriny Amori100% (1)

- Architecture As Human InterfaceDocument201 pagesArchitecture As Human InterfaceziadaazamPas encore d'évaluation

- "Art and Science of Building in Concrete: The Work of Pier Luigi Nervi " by Mario Alberto ChiorinoDocument9 pages"Art and Science of Building in Concrete: The Work of Pier Luigi Nervi " by Mario Alberto ChiorinoPLN_ProjectPas encore d'évaluation

- Role of Light On ArchitectureDocument11 pagesRole of Light On ArchitectureMonica Rivera100% (1)

- Pelkonen What About Space 2013Document7 pagesPelkonen What About Space 2013Annie PedretPas encore d'évaluation

- Atelier Bow-Wow's Small Case Study Houses at REDCAT GalleryDocument1 pageAtelier Bow-Wow's Small Case Study Houses at REDCAT GalleryDorian VujnovićPas encore d'évaluation

- BALLANTYNE, SMITH - Architecture in The Space of FlowsDocument34 pagesBALLANTYNE, SMITH - Architecture in The Space of FlowsNina Alvarez ZioubrovskaiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mies van der Rohe's Influence on Five ArchitectsDocument9 pagesMies van der Rohe's Influence on Five ArchitectsPabloPas encore d'évaluation

- Frank Lloyd Wright & Japanese Architecture - A Study in InspirationDocument18 pagesFrank Lloyd Wright & Japanese Architecture - A Study in Inspirationsiddhantsinha88Pas encore d'évaluation

- Responsive ArchitectureDocument26 pagesResponsive ArchitectureEli Kafer100% (3)

- Kevin Klinger PDFDocument226 pagesKevin Klinger PDFfernandowfrancaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tadao AndoDocument2 pagesTadao AndoLakshiminaraayanan Sudhakar100% (1)

- The Origins and Influence of the New Brutalism Architectural MovementDocument30 pagesThe Origins and Influence of the New Brutalism Architectural MovementMallika AroraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Architecture of InterpretationDocument269 pagesThe Architecture of InterpretationNithya SuriPas encore d'évaluation

- Inflection 01 : Inflection: Journal of the Melbourne School of DesignD'EverandInflection 01 : Inflection: Journal of the Melbourne School of DesignPas encore d'évaluation

- George Lincoln Rockwell - This Time The WorldDocument321 pagesGeorge Lincoln Rockwell - This Time The WorldNigger50% (2)

- European Commission document on regulatory standards for strong customer authenticationDocument31 pagesEuropean Commission document on regulatory standards for strong customer authenticationstipsa592Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Structure and Ground State Dynamics of Ar-IHDocument7 pagesThe Structure and Ground State Dynamics of Ar-IHstipsa592Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sea 34Document371 pagesSea 34craiglistemail09Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Globalisation of Modern ArchitectureDocument30 pagesThe Globalisation of Modern Architecturestipsa59250% (2)

- Believing Is KnowingDocument2 pagesBelieving Is Knowingstipsa592Pas encore d'évaluation

- Imagination as a Faculty of Religious TruthDocument9 pagesImagination as a Faculty of Religious Truthstipsa592Pas encore d'évaluation

- Labour Manifesto 2015Document86 pagesLabour Manifesto 2015conorPas encore d'évaluation

- ULN200x, ULQ200x High-Voltage, High-Current Darlington Transistor ArraysDocument34 pagesULN200x, ULQ200x High-Voltage, High-Current Darlington Transistor ArraysErnesto Alonso González RodríguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Ending Law Enforcement ViolenceDocument121 pagesEnding Law Enforcement Violencestipsa592100% (1)

- AASHTO 93 Guide For Design of Pavement StructuresDocument624 pagesAASHTO 93 Guide For Design of Pavement StructuresRicardo Alfaro100% (18)

- Wagner Otto-Modern Arch 198Document202 pagesWagner Otto-Modern Arch 198Marta Donoso Llanos100% (2)

- Fashion in Motion Kansai YamamotoDocument2 pagesFashion in Motion Kansai Yamamotostipsa592Pas encore d'évaluation

- AASHTO 93 Guide For Design of Pavement StructuresDocument624 pagesAASHTO 93 Guide For Design of Pavement StructuresRicardo Alfaro100% (18)

- Architecture Competition Annual 2008Document156 pagesArchitecture Competition Annual 2008stipsa592Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anonimno Surfanje I Zastita Od SpijunazeDocument42 pagesAnonimno Surfanje I Zastita Od SpijunazeperopericblPas encore d'évaluation

- AASHTO 93 Guide For Design of Pavement StructuresDocument624 pagesAASHTO 93 Guide For Design of Pavement StructuresRicardo Alfaro100% (18)

- Baumit Sustavi S Toplinskom Zbukom PDFDocument8 pagesBaumit Sustavi S Toplinskom Zbukom PDFAntePas encore d'évaluation

- "The Architecture of Invention": The Lemelson-Mit Program School of Engineering Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyDocument51 pages"The Architecture of Invention": The Lemelson-Mit Program School of Engineering Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyCik AnoiPas encore d'évaluation

- QCT - Condensador TesterDocument2 pagesQCT - Condensador TesterAddul Omman NailPas encore d'évaluation

- Calypso GenreDocument14 pagesCalypso GenreLucky EluemePas encore d'évaluation

- On Lutes, Tablature and Other ThingsDocument79 pagesOn Lutes, Tablature and Other ThingsMarcus Annaeus Lucanus100% (4)

- Culinary Journey en PDFDocument28 pagesCulinary Journey en PDFJenny RodrìguezPas encore d'évaluation

- B Give Short Answers To The QuestionsDocument2 pagesB Give Short Answers To The QuestionsVũ Thuỳ LinhPas encore d'évaluation

- Benefits of Gayatri Mantra, Chandi Homam, Dhanvanthri HomamDocument3 pagesBenefits of Gayatri Mantra, Chandi Homam, Dhanvanthri HomamVedic Folks0% (1)

- Creative Writing - How To Develo - Adele RametDocument137 pagesCreative Writing - How To Develo - Adele RametSecretx Sahydian100% (1)

- Joseph Brodsky - A Room and A HalfDocument5 pagesJoseph Brodsky - A Room and A Halfkottzebue0% (1)

- Pastyme ScoreDocument2 pagesPastyme ScoreMatthew JelfPas encore d'évaluation

- History of Anglo-SaxonsDocument13 pagesHistory of Anglo-SaxonsShayne Penn PerdidoPas encore d'évaluation

- Hadith of The Holy Prophet Muhammad Peace Be Upon HimDocument9 pagesHadith of The Holy Prophet Muhammad Peace Be Upon HimRaees Ali YarPas encore d'évaluation

- Vernacular Architecture of MalaysiaDocument9 pagesVernacular Architecture of MalaysiaJudith JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Paid Client Sample Data CRM HackerDocument12 pagesPaid Client Sample Data CRM HackerUpendraPas encore d'évaluation

- Angelica Zambrano - 1st Experience PDFDocument27 pagesAngelica Zambrano - 1st Experience PDFRose M.M.50% (2)

- Essay On Indian Culture and Tradition - Important IndiaDocument3 pagesEssay On Indian Culture and Tradition - Important IndianapinnvoPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Modicare Product With Price ListDocument4 pagesList of Modicare Product With Price ListGunjan89% (19)

- Dissertation PDFDocument61 pagesDissertation PDFÍtalo R. H. Ferro100% (1)

- ALL About PICKUP WindingDocument21 pagesALL About PICKUP WindingMochamad Irfan100% (2)

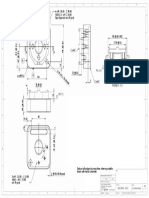

- NX CAD ProjectDocument1 pageNX CAD ProjectKarthik Kumar YSPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Summary PDFDocument2 pagesCritical Summary PDFDillen NgoPas encore d'évaluation

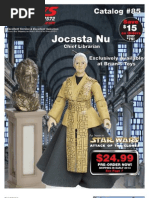

- Brian's Toys Product Catalog #85 (August 2012)Document32 pagesBrian's Toys Product Catalog #85 (August 2012)Brian's Toys, Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elements of Drama and Types of DramaDocument29 pagesElements of Drama and Types of DramaDaisy Marie A. Rosel100% (1)

- A Prayer of GratitudeDocument1 pageA Prayer of GratitudeJena Woodward NietoPas encore d'évaluation

- GBC MP2500ix Parts ManualDocument32 pagesGBC MP2500ix Parts ManualToddPas encore d'évaluation

- $sanderson KhmersDocument114 pages$sanderson KhmersRasa LingaPas encore d'évaluation

- Web Application Development: Bootstrap FrameworkDocument20 pagesWeb Application Development: Bootstrap FrameworkRaya AhmadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Places to Visit This Summer in the West MidlandsDocument1 pagePlaces to Visit This Summer in the West MidlandsNacely Ovando CuadraPas encore d'évaluation

- Action Plan and Journalism Training MatrixDocument5 pagesAction Plan and Journalism Training Matrixryeroe100% (2)

- All Over The World - Literary AnalysisDocument2 pagesAll Over The World - Literary AnalysisAndrea Gail Sorrosa100% (1)

- Present Simple and Past Simple Tenses in EnglishDocument1 pagePresent Simple and Past Simple Tenses in EnglishAnonymous SLYi8ORABPas encore d'évaluation