Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Sacrifice As The Ideal Hunt

Transféré par

Anonymous acFnttvTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sacrifice As The Ideal Hunt

Transféré par

Anonymous acFnttvDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

bs_bs_banner

Sacrice as the ideal hunt:

a cosmological explanation

for the origin of reindeer

domestication

R a n e Wil l e r s l e v Aarhus University

Piers Vi te bsky University of Cambridge

Anatoly Alekse ye v M.K. Ammosov North-Eastern Federal University, Yakutsk

The Siberian Northeast shows striking parallels between the cosmologies of hunters and reindeer

herders. What may this tell us about the transformation from hunting to pastoralism? This article

argues for a structural identity between hunting and sacrice, and for the domestication of the

reindeer as the result of hunters efforts to use sacrice to control the accidental variables of the

hunt. Hunters can practise their ethos of trust with prey only through highly controlled ritual

enactments. We describe two: the famous bear festival of the Amur Gulf region and the consecrated

reindeer of the Eveny. Both express the same overall logic by which sacrice functions as an ideal

hunt. The animal is involved in a relation not of domination but of trust, while also undergoing a

process of taming. We therefore suggest that the reindeers domestication may be based not only

on ecological or economic adaptations, but also on cosmology.

Introduction: diversied economies but a unied cosmology

Some 2,000-3,000 years ago, the first reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) were tamed in

Siberia. This step was never taken in the American North, where reindeer are called

caribou and exist only in the wild.1 We know almost nothing about how and why the

initial taming happened in Siberia, probably in the Sayan mountains or east of Lake

Baikal, and probably by the ancestors of todays Evenki and Eveny people (Pomishin

1990; Skalon 1956; Vainshtein 1980; Vasilevich & Levin 1951).2 Yet the consequences have

been dramatic: the ability to ride on reindeer radically altered the way people were able

to move and settle throughout North Asia, their modes of production, their distribution of resources, and their organization of labour. Anthony Leeds (1965: 100) has noted

the strong social hierarchy among pastoralists everywhere, and Robert Paine (1971: 166)

has specifically argued that reindeer-exploiting societies show an increased emphasis

on ownership and private property. Tim Ingold has summarized most of these points

when writing that the pastoral mode is the precise opposite of hunting, which is

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

2 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

Figure 1. Eveny herders loading saddle-bags onto a reindeer before moving to their early autumn

campsite in the Verkhoyansk Mountains. It is August, the leaves are turning yellow, and the rst snow

will come soon. (Photo by Piers Vitebsky.)

characterized by collective access to resources, indefinite productive targets, generalized

reciprocity, and the absence of any possibility of multiplicative accumulation (1980:

223).

At first, humans rode small numbers of domesticated reindeer to hunt their wild

cousins (sledges came much later: Vainshtein 1980; Vasilevich & Levin 1951). Starting

from Russian colonial times (Krupnik 1993: 160-84) and on into the Soviet twentieth

century, they and other indigenous groups like the Chukchi, Koryak, and Eveny

developed large-scale herds in which most reindeer are kept for meat. While the great

majority of Siberian peoples took on reindeer herding and combined it with hunting,

a few groups like the Upper Kolyma Yukaghir never adopted the domestic reindeer, but

continued living entirely from hunting.3

When the three authors of this article met in 2013 to discuss the transformation from

hunting to pastoralism in Northeast Asia4 and compare notes on different indigenous

groups, major differences in social and economic organization were apparent, even

after seventy years of determinedly homogenizing Communist rule. The Yukaghir

hunters of the Upper Kolyma and the reindeer-herding Chukchi and Koryak of

Chukotka and Kamchatka represent two opposed positions on the hunter-pastoralist

continuum. The Yukaghir, who have no reindeer and among whom a hunter is

expected to share his spoils with the entire community, are highly egalitarian with no

authoritarian leadership or marked differences in personal wealth (Willerslev 2007:

35-42). The Chukchi and Koryak, by contrast, are distinctly hierarchical even today,

with social status largely determined by the number of privately owned reindeer, and

extended families made up of poorer households clustered around a wealthy reindeer

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 3

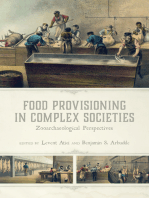

Figure 2. Indigenous peoples of Northeast Siberia mentioned in this article. Locations and

boundaries are approximate. Populations are extremely sparse, and interspersed with Russians and

other settlers.

owner. The Eveny of Kamchatka somewhat resemble egalitarian hunters, while those in

Yakutia (Alekseyev 1993; Vitebsky 2005) are somewhere in between, with large herds of

mixed state and private ownership.

However, what we found puzzling is that these radical socio-economic differences

are not reflected on the plane of cosmology, and this is perhaps the greatest mystery

about the hunting-to-pastoral transformation in North Asia. When comparing the

indigenous cosmologies we found close parallels, amounting almost to identity, regardless of economy. All groups in the region are animistic (cf. Pedersen 2001), have similar

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

4 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

forms of shamanism, and engage with spirit masters of animals and places in the

landscape. All are highly concerned with the ritual treatment of the bones of the dead,

humans and animals alike, so as to ensure their continued rebirths (cf. Willerslev

2013a). Most importantly for the argument pursued here, we established a family

resemblance (Valeri 1994: 104) between hunting and blood sacrifice, as two ritualized

ways of taking life. Indeed, when we compared hunting throughout the region with the

ideal-typical scheme of sacrifice among those who have domestic reindeer, it became

clear that there is a strong resemblance between the ritualized killing of wild animals

and the sacrifice of domesticated reindeer.

We asked ourselves what this similarity on the cosmological plane might tell us

about the causes and mechanisms of the crucial transformation from hunting to

pastoralism. Could it be that rather than marking a radical shift in peoples relationship to animals, this transformation represents a continuation and refinement of the

hunters attitude towards prey? These are the basic questions we set out to explore in

this article. We believe that by studying the complex pattern of common features and

differences between hunting and ritual blood sacrifice, we may find new answers to the

old question about what led to the initial taming of the reindeer.

Cosmology and epochal change

The trigger for the first taming, and thus for beginning the process of domestication,

of the reindeer has long been debated. Almost all explanations are ecological or

economistic, pointing either to a diffusion of technology through imitation of southern

pastoralist cultures based mainly on horse-riding (Ingold 1980: 282-3; Laufer 1917: 118;

Figure 3. Eveny women feeding reindeer with salt to keep them tame. One tradition says that wild

reindeer were rst attracted by the salt in womens urine. Today tame reindeer still pester anyone

trying to urinate in peace. (Photo by Piers Vitebsky.)

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 5

Vainshtein 1980; Vasilevich & Levin 1951) or to ecological adaptation, favouring increasingly efficient patterns of environmental exploitation (Bogoras 1924: 234; Hatt 1918;

Krupnik 1993: 166; Sirelius 1916; Zeuner 1963: 46). Thus, the historical forces of cause

and effect are related to adaptive and technological operations, rather than

to spiritual belief. Indigenous cosmology generally appears as secondary to the environmental and technological conditions of life, so that it cannot in itself initiate any

epochal change. The Danish cultural geographer Gudmund Hatt, once a major player

in this debate, scathingly declared that to search for the origin of purely economic

forms in ... religious ideas or practices ... is about as preposterous as to regard a tree as

the natural result of the lianas and epiphytes it carries (1918: 253).

However, we believe that Hatts analogy is itself preposterous. Some of the major

shifts in history, and indeed in our own day, occur through religious or other ideological pressure. Why should the triggers for the domestication of reindeer not have

included cosmological or spiritual elements (cf. Kwon 1998: 125 n. 7)?

This is not to deny that economic and ecological factors may have played an important part in the transition from hunting to pastoralism. However, these do not reveal

what elements in the cosmology of local hunters allowed them to start taming their

principal game, the reindeer. The argument in terms of efficient resource management

is not sufficient, since, as we shall see, there are key elements in hunters cosmology that

work directly against any form of taming. Thus, the impetus for early reindeer domestication is as much a cosmological puzzle as an economic one.

It is this cosmological puzzle that we set out to resolve here by systematically

comparing the two basic ritual modes of killing animals in the Siberian North, hunting

and sacrifice. The intricate parallelisms, contrasts, and criss-crossings that we detected

between these suggest that it makes little sense to identify sacrifice solely with the use

of domestic animals. Our approach implies a break with a mainstream literature that

insists on a radical contrast between sacrifice and hunting (Valeri 1994: 111): according

to this literature, sacrifice by definition involves the ritual slaughter of a domestic

animal and thus is a phenomenon of pastoral peoples. Since one can sacrifice only what

one owns, it makes no sense to propose that hunters involve their wild animals in

sacrifice. Hunting is customarily seen as a predatory activity, implying that the animal

killed has no sacramental value (Valeri 1994: 111). As claimed by Jonathan Z. Smith, a

historian of religion to whose work we shall return below, Animal sacrifice appears

to be, universally, the ritual killing of a domesticated animal by agrarian or pastoralist

societies (1987: 197, original emphasis; see also Jensen 1963: 163-90).

However, this conventional contrast between hunting and sacrifice has been challenged by other scholars who argue convincingly for a plausible grounding if not

origin of ritual blood sacrifice in hunting as a ritual act (Burkert 1972: 12-22; Howell

1996: 15-16; McKinnon 1996; Meuli 1946; Valeri 1994). We start from Ingolds article

Hunting, sacrifice and the domestication of animals, in which he compares hunting

and sacrifice by situating both within a broader unified circumpolar cosmology, bringing together materials from both Eurasia and North America. Ingolds conclusion, from

a somewhat Frazerian treatment of the subject (1986: 244), is that the hunting and

pastoralist cosmologies run so close to one another that each can, in fact, be seen as a

model of the other:

[T]he sacrificial rite is already prefigured in native conceptions surrounding the conduct of hunting.

All that is necessary to bring it out is to transpose mastery over herds from non-human to human

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

6 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

persons, which is of course a corollary of their domestication, and marks the transition from a

hunting to a pastoral economy (1986: 272).

This quote anticipates Ingolds later article From trust to domination, in which he

suggests that pastoralist societies fundamentally reconfigure the productive relations

between animals and humans, replacing trust between hunters and prey with domination by herders over livestock (Ingold 2000: 70-1). Trust refers here to the widely

reported idea among hunting peoples that a successful kill of an animal is the result of

its own collusion in being taken (2000: 69). Domination, by contrast, refers to a

situation in which the herdsman himself takes life-or-death decisions concerning what

are now his animals [as] protector, guardian and executioner (2000: 72).

We shall use Ingolds pioneering analysis for further exploring the transition from

wild reindeer hunting to reindeer domestication, while squeezing his Frazerian overview of the circumpolar North down to a tighter focus on the Siberian Northeast. In

proposing a fundamental ritual identity between killing in the hunt and in sacrifice,

Ingolds thesis supports our view that a major contributory cause of reindeer domestication may lie in cosmological concerns, rather than just in ecological adaptations and

the diffusion of technology.

However, Ingolds schema needs further refinement. His model of reindeer herding,

which is based largely on his own fieldwork in Finland (Ingold 1976), was elaborated in

the 1970s and 1980s. However, he did not read Russian, and before the 1990s there was

very little information available in Western languages on the Russian North, where

most of the worlds domesticated reindeer live. Ingold drew on old classical studies by

scholars such as Waldemar Bogoras (1904-9) and Waldemar Jochelson (1908), but since

then a large body of new ethnographic information has become internationally available. Also the notion of domestication, in the conventional sense of selective breeding,

cannot easily be applied to Siberia, despite traditional practices and the Soviet state

farms scientific management regimes. Apart from the few reindeer that have their own

names and are trained to carry people and luggage, pull sledges, or be milked, most

of the other animals form what may be called a lumpen herd. They are only semidomesticated and certainly not tamed, since they can be caught only by lasso and if

unattended may revert to a feral or semi-wild state (Vitebsky 2005: 25, 377). To complicate the picture still further, our ethnographic examples from Northeast Siberia will

show that the distinction between trust and domination is quite clearly more ambiguous than Ingold proposes.

The hunted animal gives itself up

However, it is not only the concept of domestication which needs refinement: so does

our understanding of hunting. Does a hunted animal really give itself up to be killed

in a relationship of simple trust? It is true that ethnographic reports have promoted a

particular image of hunting in the circumpolar North as based not on predation but on

an intimate, mutualistic, and even non-violent relationship of reciprocal sympathy and

sharing between hunter and prey in which every aspect of violence is screened out.

Heonik Kwon describes how a group of Evenki called Orochon abandon ordinary

speech in favour of a special linguistic code which deliberately conceals the reality of

being a human predator (Kwon 1998: 118; see also Anderson 2002: 125). David Anderson

writes that for Evenki ... the [reindeer] which shares its body with the hunter and his

or her kin is thought to agree to surrender itself for consumption as part of a common

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 7

struggle to preserve life (2004: 14). Likewise, the Eveny hunter described by Willerslev

and Ulturgasheva declares to the killed animal: You came to me out of your own

free will, please have pity on us and do not harm us (2012: 55). Often, the violence is

transformed into erotic imagery. Among the Eveny of Yakutia, a successful hunt is

foretold by an erotic dream involving the daughter of the master of the animals

(Vitebsky 2005: 265, 302, 346). Willerslev (2007: 101) describes how the Yukaghir hunters soul travels in dreams to the animal spirit and the two have sexual intercourse. The

feeling of lust evoked in the spirit is then extended to the animal prey, which the next

morning will run towards the hunter expecting a sexual climax. Similarly, Jochelson

writes that the Yukaghir hunt depends on the goodwill not only of its guardian spirit

but also of the animal itself, which must like the hunter (Jochelson 1926: 146). The

hunters clothing is also part of the seduction of the prey, and must be carefully and

beautifully made to please the spirit of the animals (Chaussonnet 1988: 210).

Indeed, when reading through ethnographic accounts of Siberian hunting, one

could conclude that the successful hunter achieves his goal, not primarily through

practical skill, but rather through an intimate relationship of trust with the animal and

its associated spirit. Ingold draws on similar accounts from the Eurasian and American

North when writing that

a hunt that is successfully consummated with a kill is taken as proof of amicable relations between the

hunter and the animal that has willingly allowed itself to be taken. Hunters are well-known for their

abhorrence of violence in the context of human relations, and the same goes for their relations with

animals: the encounter, at the moment of the kill, is to them essentially non-violent (2000: 69,

original emphasis).5

Words, deeds, and the ideal hunt

However, can we really take at face value these standard ethnographic reports that

indigenous hunting is based on trust and non-violence? Or is this perhaps an example

of anthropologists staying too much inside the informants models or at least staying

too much with what they appear to be saying in their official discourse?

As anthropologists, we know there may be important discrepancies between what

people do and what they say or think they do (cf. Bourdieu 1994: 141). As an extreme

example, the bear is held in awe throughout the circumpolar North as an animal of

exceptional spiritual power, and is given epithets like Lord of the Forest (Willerslev &

Pedersen 2010: 269-73). The great summary of all this is Irving Hallowells classic essay

Bear ceremonialism in the northern hemisphere (1926). Hallowell describes how

indigenous peoples around the entire circumpolar North see bear hunting as a sacred

act that must be performed according to strict rules of etiquette (we shall turn to bear

sacrifice below). Knives and spears must be used (not guns), the hunter must sing to the

bear, it must be tackled in a fair stand-up fight or hand-to-hand combat, and the fatal

wound must be bloodless.

Is all this plausible? In an influential essay, The bare facts of ritual, Smith questions

Hallowells account: Can we believe that any animal, once spotted, would stand still

while the hunter recited dithyrambs and ceremonial addresses? Or ... sang love songs?

... Is it humanly conceivable that a hunter ... will not boast of his prowess? (1988: 60).

Smiths answer, derived from the armchair on the grounds of common sense and

our [sic] sense of incredulity, our estimate of plausibility, is No: all Hallowells

sources are an idealized fiction. In less extreme critiques, Anderson (2002: 127) also

criticizes the idea that animals surrender themselves freely, and Knight objects to the

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

8 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

hunting-as-sharing hypothesis promoted by Ingold (2000) and Nurit Bird-David

(1992), on the grounds that hunting is a relatively short-lived event that happens in the

here and now, whereas a relationship consists of a series of interactions and therefore

exists over a longer span of time (Knight 2012: 336).

We agree with Knight that human-animal co-sociality is found rather with

pastoralists, whose animals have shed their fear of humans as predators (2012: 343), and

will make use below of Smiths notion of idealization (though he is quite wrong when

his common sense leads him to expect a hunter to boast of his prowess that would be

a sure way to anger the animals and their spirits, cf. Kwon 1998: 116; Vitebsky 2005: 269;

Willerslev 2007: 38). But we are not keen on the way this kind of no-nonsense critique

tends to reduce hunting to a rational, practical act of predation (similarly to ecologistic

theories about the domestication of reindeer). None the less, it is hard to deny that Smith

and Knight have a valid point. Such approaches challenge the standard ethnographic

reports of trust between hunter and prey, and force us to pause and consider what we

really mean when saying that animals give themselves freely so that hunting is essentially

non-violent. Why is it that the selfsame ethnographies that describe animals as willing

prey often also present drawings of an arsenal of devious spring traps, deadfalls, and

self-triggering crossbows, designed to catch animals unaware (see Bogoras 1904-9: 13847; Jochelson 1926: 378-82; Willerslev 2012: 193-200)? Worse, Hitoshi Watanabe (1973: 35)

reports how the Ainu used to kill the brown bear by using poisoned arrows. There is no

sign here of the animals eagerness to surrender themselves.

But the answer is not to ignore the evidence as Smith does and aim for a crude Yes

or No. In fact, indigenous hunters know very well that they do not actually hunt the

way they say they hunt, making the animal surrender itself through songs, clothing, and

eroticism. So why do they talk as if this is what they do? We suggest that hunters

discourses about hunting, which are then passed on by anthropologists, do not so much

denote the hunt as it is but rather represent an ideal, which stands in conscious contrast

to the course of things during actual hunting. The notion of the ideal or perfect hunt

is part of Smiths general view of the work of ritual, which deals with the issue of

relating that which we do to that which we say or think we do and takes upon itself the

laborious task of patching up holes and stopping gaps (1987: 194).

Smiths notion of an ideal hunt echoes Ingolds notion of trust. But unlike Ingold,

Smith does not believe that this exists in everyday reality. Smith is presumptuous when

he uses his armchair scholars common sense to deny any ethnographic evidence

which defies his prejudices, but helpful when he questions the actual performance of

songs and literal non-violence. The implication we take from this is that the hunter is

trapped in a sort of irreducible paradox or double bind. The term was made famous by

Gregory Bateson (2000 [1972]: 206-8; Bateson, Jackson, Haley & Weakland 1956) and

refers to a communicative matrix in which two messages or rules negate each other,

each on a different logical level, and yet neither of them can be ignored or defied. This

contradiction can give rise to extreme anxiety, since no matter what a person does, he

cant win (Bateson et al. 1956: 251): If you do not do A, you will be damned. But if you

do do A, you will also be damned. Many double binds are further complicated in that

they involve different logical levels, so that what you must do (in order to survive or be

safe) on one level threatens your survival or safety on another. According to Bateson,

double binds are at the root of both creativity and schizophrenia (to say nothing of

ritual). The difference is whether or not one is able to identify and break out of the bind

by reducing its intensity or shifting the nature of the double-binding relationship.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 9

Figure 4. Killing a brown bear in the wild is usually a messy affair, since the variables of the hunt

cannot easily be controlled. (Photo by Rane Willerslev.)

We draw attention to the double bind here because in the hunters ongoing relationship with animal prey there is a recurrent paradox: on the one hand, the hunting

ideal represents a supreme spiritual law, and there is a widespread belief that animals or

their spirit owners take serious offence if the animals are not treated correctly with all

sorts of ritual niceties (Kwon 1998; Vitebsky 2005: 263-4; Willerslev 2004b; 2007: 129;

Willerslev & Ulturgasheva 2012: 55). On the other hand, the actual conditions of

hunting make it difficult and often impossible to live the ideal. This is why everyday

practical hunting is subject to another set of rules that contradict the highly moralized

ethos of hunting, but which for pragmatic reasons are tacitly accepted. Such are the

hunters killing of prey by means of physical force, cunning traps, or magical tricks. At

the heart of the hunters double bind lies the problem of the animals inherent fear

of predators, which makes it force the hunter on long and exhausting chases before he

finally takes it down in a messy killing. This discrepancy between the ideal, in which the

docile animal gives itself up to the hunter, and the reality in which animals are manifestly capricious and bent on escape, and in which hunters have to resort to brutality

and deceit to bring them down, is a prevalent theme in the mythology of Siberian

peoples. Yukaghir and Eveny myths are full of stories of how every aspect of violence in

hunting must be relegated to absolute silence, otherwise terrible things will happen to

the hunter and his kin (cf. Jochelson 1926: 177). Eveny hunters must never say I killed

a bear but use coded euphemisms such as I obtained a child (Vitebsky 2005: 269).

Likewise, Yukaghir hunters use coded expressions to avoid naming the hunted moose

(elk) by its real name, and instead of the word kill they make a downward movement

with their hands to indicate that the animal has fallen. Hunters will not sharpen a knife

or clean a gun on the day of the hunt, as this would reveal their violent intention and

provoke the anger of the animal spirits (Willerslev 2001; Willerslev 2007: 100-1).

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

10 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

The ideal hunt fullled in sacrice

This double bind, reflecting a discrepancy between words and deeds in hunting, may

well be the archetypal tension of life in the circumpolar North, where everyones

survival depends on animal economies that are highly moralized. This tension finds

expression in numerous actions and operates across a range of domains from the

psychological to the cosmological. We argue that the need to overcome this double bind

may have been a key motivator in transforming the actual hunt into the highly controlled pattern of ritual blood sacrifice. This would explain why the ideal hunt has the

same logic as the typical scheme of sacrifice among pastoralists, and furthermore it

suggests that the urge to sacrifice may have been a significant driver behind the domestication of the reindeer.

Both hunters and herders depend on the animals meat for food, and both believe

that its soul will go to the spirits and be recycled into a new body of the same species

(Ingold 1986: 246; Jordan 2003; Pedersen and Willerslev 2012: 477; Vitebsky 2005: 263;

Willerslev 2007: 31-2; 2009: 696). Both are equally concerned to ensure this reincarnation by treating the carcass in accordance with strict rules, especially the bones, which

are widely thought to contain the animals soul and its potential for rebirth. Thus the

animals death is at once an act of destruction and a rite of renewal, and it may be this

which lies behind the talk of non-violence. The stock of animal souls is finite and the

shocking boast that I killed an animal would block its rebirth for ever.

To support our thesis that ritual blood sacrifice is the lived-out equivalent of the

ideal hunt, we shall take a closer look at how a sacrificial victim is ritually treated. We

shall start with reindeer sacrifice among the Chukchi and Koryak, who are well known

to Willerslev through direct observations, and whose sacrificial practices have also been

well documented in the classical works of Bogoras (1904-9: 368-85), Harald Sverdrup

(1939: 135-75), and Jochelson (1908: 87-97).

A dead persons sledge reindeer is sacrificed at the grave, as are tens of other ordinary

reindeer at an autumn ritual for the dead. Such reindeer must be perfect and unblemished, with no limp or broken antlers. People dress in their finest fur clothing, highly

decorated with coloured bands and beadwork, to please not only other humans but also

the reindeer, which is said to take pleasure from its owners colours (cf. Rethmann 2001:

136). The reindeer is captured from the herd by lasso and dragged to the sacrificial place.

People sing to calm the animal down, saying that it must not be frightened but be a

willing victim, otherwise the sacrifice will not be accepted by the spirits (cf. Jochelson

1908: 94). It is of paramount importance that the reindeer stands stock-still and does

not resist. If it is not killed at the first blow, this means that the spirits do not accept the

sacrifice (Jochelson 1908: 94). The reindeers head is placed so that it faces the direction

of the receiving spirits (Bogoras 1904-9: 368; Sverdrup 1939: 168). A branch of willow is

put under its hindquarters as a bed so that it does not get cold, and water is smeared

on its nose to quench its thirst. After a short prayer,This is for you (Jochelson 1908: 98),

or Oh High Spirits, this is for you, make the herds thrive (Willerslev 2013b: 145),

the entire animal is cooked and eaten by everyone.

We see how the sacrificial ritual is equivalent to the hunt in key respects. The

beautiful clothing to please the animal, the singing, the identical etiquette in the

treatment of the animals corpse, and the sharing of meat with kin and neighbours

are all well documented among the regions hunters too. Also, the prayers contain

essentially the same appeal for success and luck. For example, the Yukaghir hunter

will feed the seasons first sable with food and drink and lay it on a small bed, saying:

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 11

Figure 5. Ritual blood sacrice achieves what hunters say they do but cannot do: a Chukchi man in

northern Kamchatka has killed a perfect white reindeer with a single blow to the heart. Note that the

animal was not tethered. (Photo by Rane Willerslev.)

Go and say to your kin how well you have been treated and let them come to my

house in great numbers (Willerslev 2012: 77). Above all there is the same common

idea that the animal is not killed as an act of violence, but rather freely offers itself

to them.

However, while the cosmological make-up of hunting ritual and sacrifice are very

similar, they differ greatly regarding human control (Ingolds domination). This is the

key transformation within different variants or fulfilments of a basic north Siberian

cosmology. Ritual perfection is difficult or impossible to achieve in actual hunting,

not least because the animal is unlikely to respond in the required ritual manner. In

sacrifice, by contrast, all the accidental variables are controlled, so that the animal is

compelled to play its part rather than run away, just as it is (usually) compelled to

assume the correct posture which makes it possible to kill it among the Chukchi and

Koryak with a smooth clean blow to the heart. Among the Eveny of Yakutia, a sacrificial

reindeer is generally not pierced but strangled with a lasso in order to avoid actual

bloodshed. Thus when these pastoralists sacrifice a reindeer, they are effectively doing

what the hunters say they do, but cannot do: killing it in an essentially non-predatory

manner. Indeed, Smith is right that a wild animal does not wait while the hunter sings

to it or makes a speech, but he misses the clue to the imagination behind this idea. In

hunting, what always falls short of the ideal is the performance; in sacrifice the theatrical tableau is complete.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

12 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

Magic and sorcery in the ideal hunt

It is here that we can see how sacrifice can represent the perfect hunt, in which all the

distressing elements of unpredictability, accident, and chance are factored out. This

allows hunters successfully to solve the discrepancy between word and deed, between

their cosmological ideal and their actual behaviour. We believe that this is a strong

motive to push hunters towards developing a pastoralist regime, and that it could

plausibly have been a driver historically.

However, within its overarching common cosmology, Northeast Siberia remains

very diverse. Even though the domestication of reindeer now predominates in the

region, there are some groups, such as the Upper Kolyma Yukaghir, who have not gone

down this route but have confined themselves to hunting without the aid of reindeer

for transport. Even the Evenki and Eveny still combine hunting with their large-scale

reindeer herding. Despite the apparently perfect sacrificial scheme, why do some of

these hunters not adopt it? Are they aiming at a similar result without domestication?

In our view, sacrifice is only one of a wider range of ways of overcoming the hunters

double bind. There are alternative methods of control which amount to a non-material

counterpart to the technology of traps, but are more directly targeted at influencing

the volition of the animal rather than just ambushing its flesh. The Eveny use secret

language when hunting so that eavesdropping animals will not recognize their own

names (Vitebsky 2005: 268-9). The Yukaghir lure sable by bribing the spirits with

bottles of vodka left along their trap lines (Willerslev 2012: 78) or by asking God or a

saint for help: I stand here, Gods servant. I make the sign of the Cross and walk in

prayer for blessing. I set the trap for the black sable. May it bring me luck! (Willerslev

2012: 90).

Another important technology is sympathetic magic, a term that was famously

introduced by James Frazer. This is based on the principle that like produces like, or

Figure 6. Yukaghir hunter with dying moose. (Photo by Rane Villerslev.)

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 13

that an effect resembles its cause. [So] the magician infers that he can produce any

effect he desires merely by imitating it (Frazer 1959 [1911]: 52). Frazer assigned sympathetic magic to a mistaken form of causal thinking, but Michael Taussig (1993; see also

Willerslev 2004a) argues rather that it is a particular way of perceiving things. To mimic

something is to be sensuously filled with that which is imitated, yielding to it, mirroring

it and hence imitating it bodily. It is, Taussig claims, a particular and powerful way

of comprehending, representing, and above all controlling the surrounding world

(Willerslev 2004a: 638-9).

We find evidence of this type of magic all over Siberia. The Evenki, Mansi, Ket, and

Khanty carve figures of prey, on the principle that if the pictorial soul is in the hunters

possession the animal itself will follow soon (Lissner 1961: 245). The Ainu call this

magic for binding up ... the life, spirit or soul of a person [human or animal alike]

(Batchelor 2013: 25). An elderly Yukaghir hunter explained to Willerslev (2007: 125-6)

how his mother could control a moose by imitating it. She would walk around on her

hands and knees, grunting and swinging her head back and forth like a real moose.

When she started eating a willow bush that had been placed in the middle of the room,

the father would hand the narrator (who was a small boy at the time) a wooden bow

and a blunt arrow with which he would shoot his grandmother in the heart. She would

kick her legs like a dying moose, and then direct the hunters to a particular spot in the

forest where she had tied up the moose. Sure enough, the moose stood motionless, as

if carved out of a rock. This image of immobility is strikingly similar to the way

a domestic reindeer is captured by lasso, tied up and unable to run away during a

sacrificial slaughter, and we interpret these techniques as a hunters counterpart to

taming, as a way of calling forth the animals self-surrender. This lends further support

to our idea that domestication of the reindeer is about exerting a control which is

spiritual as much as economic.

However, Yukaghir call this pakostit, playing dirty tricks, and the same informant

emphasized that what the grandmother did was a great sin for which her family would

eventually pay with their lives. Similarly, the specialist Yukaghir hunter, xanice (persecutor, Jochelson 1926: 122), is feared for his magical powers as he compels a wild

reindeer or moose to run towards him by imitating its bodily movements. But though

he is successful in providing meat to his family, he too will end up the same way

(Willerslev 2007: 47-9; 2012: 135).6

This returns us to the hunters double bind. On the one hand, hunting magic echoes

(or, in evolutionary terms, prefigures) sacrificial slaughter, in that it induces the animal

to act out an acceptance of its own death. On the other hand, this magic is considered

a sin that attracts spiritual retaliation, exactly because it manipulates the animals free

will through domination. Thus, while the ideal hunt denotes everything that is good

and fair about hunting, the moment it is applied in real life by tying down the animal

it switches into something negative, a kind of sorcery. How can this be?

Here we return to Ingolds distinction between trust and domination. With trust,

the animal allows itself to be taken willingly (Ingold 2000: 69) and any attempt

to impose a response ... would represent a betrayal and a negation of the relationship

(2000: 70, original emphasis). Ingold also argues that trust is decidedly double-edged in

that it always harbours an element of risk that the other may not act favourably

towards you, as hoped, or that it may even be hostile (2000: 70). This is the dark side

of the trust relationship that we see acted out when a hunter secures the immobility of

an animal through sympathetic hunting magic. It may appear as if the animal freely

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

14 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

gives itself to him, but in actual fact its favourable response is elicited by magical

deception. The magic is a form of sorcery, and it is this which is the real betrayal of

trust. The hunters themselves see it this way too. The Yukaghir, for example, with their

absence of pastoralism, fear the Eveny as sorcerers, since they use their magic to do what

only Khozyain (the spirit master) should be doing by riding on the reindeers back: Its

a great sin and the reason why the Eveny suffered much hunger in the past. Khozyain

likes his children [the wild reindeer] to run free (Willerslev field notes).

So not only are the hunters left with the ideal of a perfect hunt that they cannot live

up to. It now appears that this cannot be solved by using imitative hunting magic,

however attractive this may be, since this deception undermines the moral principle

of trust on which the ideal is based and turns it into a dirty and underhand kind of

domination. Hunters are forever trapped with the frustration of a double bind that

forces them to celebrate an ideal that they can never live up to. This is true of many,

perhaps all, religious and ethical systems as they come up with elaborate compromises

to reconcile high ideals with the constraints of everyday reality. Within this dilemma

the sacrifice of a domesticated reindeer seems a good solution, as it creates an apparent

co-operation which is less erratic and dangerous than that induced by sympathetic

hunting magic. And indeed, this corresponds closely to the solution found in the

ancient biblical and Graeco-Roman pastoral worlds which underlie much general

theorizing about sacrifice, where an animal should show its acquiescence, for example

by eating from a handful of grain before it is killed (Burkert 1972).

But even here, the sacrificial reindeer, selected and calmed from the general herd, is

constrained by being tied up. Can there be a way of inducing co-operation that relies

neither on illegitimate magic nor on physical force? People in Northeast Siberia have

also found other elaborate solutions to this problem, and we have identified two of

these as being of particular significance. The Eveny in Yakutia have special co-operative

reindeer which are believed to sacrifice themselves, while groups in the Amur region,

who mostly have no reindeer, place a bear in a partially tamed position before sacrificing it. The angry mood of a bear undergoing sacrifice is, as we shall see, quite

different from that of a self-sacrificing reindeer. But we shall argue that these contrasting moods are part of the same overall logic by which sacrifice functions as a perfect

hunt. This happens through the creation of an appearance of acquiescence which

appears to be more unambiguously under human control than the acquiescence which

is claimed for the wild animal in the hunt, or even for an ordinary kind of reindeer in

sacrifice.

We shall describe the two cases in turn, starting with the bear.

Suckling and sacricing the bear

In the Amur Gulf area of the Siberian Far East and northern Japan, the indigenous

Nivkh, Orochon, Nanay, Ainu, and some Evenki until recently staged an annual bear

festival. Whereas comparable bear festivals in western Siberia, for example among the

Khanty (Jordan 2003: 115-24), are performed after a bear is killed in a hunt, in this

region a bear cub is captured in the wild and reared to adulthood in a quasi-tamed

state, before finally being sacrificed in an elaborate ritual in which it appears to collude

in its own death. The captured cub is reared in a domestic setting where the women

suckle it (Paproth & Obayashi 1966: 218) and it acts as playmate for their children. After

a couple of years, when it has grown too big to be kept out in the open, the bear is

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 15

confined to a cage. Here it is fattened for another two or three years, given the best of

foods, and addressed as an honourable member of the human community.

On the day of the bears killing, it is treated in exactly the same way as the reindeer

in the Chukchi and Koryak sacrifice described above. People put on their best garments

decorated with colours, elaborate beadwork, and ornaments (Kwon 1993: 94). They sing

for the bear to please it, and offer it food and drink. There is a similar parallelism in the

killing itself. The bear is tied to a pole and ceremonially addressed, being asked for

future wealth and luck. It is finally shot dead with an arrow fired at close range by the

best hunter directly into its heart. Its body is placed on a bed made of willow (Kwon

1993: 93) and people are careful to ensure that no blood is spilled on the ground, as this

would symbolize murder (Batchelor 1967 [1909]: 208). Its body is cooked and eaten on

the spot, its head with the fur attached is turned towards the mountains, and it is sent

off with food and beautiful presents to report to the spirits how well it has been treated.

Finally, the bones of the bear are carefully reassembled into the original order to ensure

its future reincarnation: The bear that comes from the mountains is believed to

return to his world and thereafter to return to be hunted again and again (Kitagawa

1961: 140).

In his essay on the bare facts of ritual, Smith moves on from ordinary bear hunting

to this specialized sacrifice, and interprets this bear festival as a ritualized way of closing

the incongruity between words and deeds, between hunters statements of how they

ought to hunt and their actual behavior while hunting (Smith 1988: 63). It is this ritual

which leads him to the idea of the perfect hunt: the humans are in control of all the

variables and this assures a reciprocity between hunter and hunted that the actual hunt

cannot achieve (1988: 64).

While we follow Smith this far, we see from a closer reading of the evidence (which

he dismisses anyway whenever it does not match his common sense) that he ignores key

ethnographic facts which reveal the bear festivals affinity with ritual blood sacrifice,

and thus its importance for our understanding of domestication in this region. What he

misses is that in between the many demonstrations of respect and worship, the bear is

deliberately teased and tormented in order to make it growl in fury. Thus Ivar Lissner

(1961: 234), who observed the bear festival among the Nivkh, describes how the bear is

tormented with a long stick while being addressed in the friendliest of terms. Young

boys also pelt the bear with stones to make it roar (Lissner 1961: 235). Batchelor (1967

[1909]: 206-11; see also Seligman 1963: 170) reports a similar tormenting among

the Ainu, who shoot at the bear with blunt arrows and thrash it with a rod, so that it

becomes thoroughly enraged. The wilder the bear becomes the more delighted do

people get (Batchelor 1967 [1909]: 208). However, when it is eventually shot in the

heart with a real, deadly arrow, they must be careful not to allow the poor beast to

utter any cries during its death struggles, for this is thought to be very unlucky (1967

[1909]: 209).

These seemingly minor details make a huge difference, since they suggest that the

aim of the ritual is not simply to bring the bear under control, which is the point of

Smiths interpretation. Rather, what is exposed is the ambiguity surrounding the

hunting project more generally, in which hunters depend on the animals favourable

response, yet where this response has to come entirely at the volition of the animal itself.

We suggest that the importance of the bears growling from fury is not its humiliation,

as has been assumed by observers of the festival (Batchelor 1967 [1909]; Lissner 1961:

234), but quite the opposite: it renders beyond any doubt that its death is not enforced

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

16 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

upon it either by magical means or by superior force. The bears struggle asserts that it

is not a slave to be commanded at the will of others, but a genuinely sovereign free spirit.

Only at the moment of death must it cease to show fury, since this would turn the signs

of its sovereignty into a defeat and humiliation, and thus a refusal to co-operate.

In this way, the hunters achieve what is impossible to achieve through either imitative magic or regular reindeer sacrifice, namely a strong display of the animals free

willpower, even while it undergoes death at their hands. In the bear festival, the

ultimate act of domination also paradoxically becomes the ultimate act of trust. The

two principles are no longer mutually exclusive (Ingold 2000: 73), but combine to

cover both sides of the same double bind. It is this conflation that allows hunters to

capture the bear, tame it, and finally sacrifice it while still fulfilling their governing ethos

of trust between human and animal.

The bear festival as the origin of reindeer domestication

What is it about the bear that makes it so significant? Even without this specialized

festival, why is the bear hunt even more highly ritualized than any other hunt? It is not

that the indigenous peoples depend on it as an important food reserve, as suggested by

Frazer (1959 [1911]: 185) and also implied by Smith. Rather, it is because the bear holds

a very special cosmological status, here as among other circumpolar peoples (Willerslev

& Pedersen 2010: 269-73). Indeed, this is the point of Hallowells masterly overview.

Both Lev Shternberg (1999 [1905]: 175) and Sergey Shirokogoroff (1935: 76) mention

that the Nivkh and Evenki in this area believe that the bears spirit controls the spirits

of other animals. Likewise, Kwon writes that for the Orochon, all the wild animals

(siro) are actually bi boyoni which means all the descendants of the bear and when

Orochon hunters acquire game in the forest, what is killed by them is a child of the

bear (1993: 95, cf. 172). In other words, the bear represents the sacred prey par

excellence, embodying, so to speak, all other wild animal species within it, in much the

same way as the spirits of the Nuer are regarded as refractions of a single conception

of God (Evans-Pritchard 1956: 107).

By taming the bear for this festival, we suggest that the hunters open up a new format

(and perhaps historical stage) in relations between animals and humans. The bear

festival transforms the most powerful being of the forest, which encompasses all other

wild animals, into a domestic being. It is not just an enactment of the ideal hunt, but a

totalizing act of taming all animals, not least the wild reindeer on which these hunters

actually depend for food. There may even be an additional, more specific link to the

origin of domestic reindeer. Almost all scholars agree that reindeer domestication

began with the Evenki. Some also argue that it was with the Evenki in this Amur region

(Vasilevich & Levin 1951), and even that the Evenki originated here (Vasilevich &

Smolyak 1956: 623) before riding their reindeer to spread so widely across Siberia.

However that may be, the Evenki in this region also staged the bear festival and have an

origin myth in which the domestic reindeer originated in a self-sacrifice by the bear,

who instructed a human to spread my fur in a pit, hang my intestines on a slanting tree

(Vasilevich 1963: 71). The human did so and the next morning the little valley was full

of domestic reindeer (Vasilevich 1963: 71).

The self-sacricing reindeer of the Eveny

The Eveny further west in Yakutia, described by Alekseyev (1993) and Vitebsky (2005),

show a similar reverence for the bear but make no attempt to capture or sacrifice it.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 17

None the less they, too, consider the bear to be the master of the wild animals that are

controlled by a spirit owner, who in this region is an old man called Bayanay. Wild

reindeer, like the bear, are subject to the regions overarching logic of hunting. They are

swift and elusive, capricious and inscrutable like Bayanay himself. In hunting them one

must find an uneasy balance between cultivating Bayanays favour and using techniques of deceit like secret language.

But when reindeer play the role of personal companions a different kind of significance emerges, and Eveny thinking offers compelling evidence that this may be how

they were originally tamed. In Eveny myth one group of primal reindeer in trouble was

helped by a compassionate human (Vitebsky 2005: 26-7). In response the reindeer

offered to serve humans ever after in exchange for protection from wolves. But another

group refused to give up their freedom and preferred to face the risks of predators for

themselves. Here, the tension between co-operation and resistance, which in the Amur

region is played out within the oscillating moods of the captured bear, is split between

the categories of wild and domestic reindeer. Though Eveny are perfectly aware that

they belong to the same species, there is no single species name that encompasses buyun

(wild reindeer) and oron (domesticated reindeer).7 The distinction is not morphological but behavioural, in terms of their different potential for sustaining a relationship

with humans.

Apart from the large general domestic herd which emerged in colonial and Soviet

times, there are two kinds, or degrees, of special domestic reindeer. Firstly, each Eveny

person has a few transport reindeer, each of them individually named and trained to

carry a saddle with a human passenger on its back in a close partnership of shared

mobility. When a person dies, his or her favourite riding deer is sacrificed on the grave

and every bone is gathered together so that the reindeer can carry its rider around in the

next world (Vitebsky 2005: 328-30). But there is another kind of reindeer which has an

even closer relationship with humans. Each person has a consecrated reindeer called a

kujjai (Alekseyev 1993: 63-72; Vitebsky 2005: 278-81, 427). A kujjai has special features,

such as extraordinary colour markings or strange hypnotic eyes. It is the most magical

kind of reindeer, and at the same time the one with the most intense attachment to a

human partner. Far from carrying anyone, it must not be tethered, ridden, or eaten, but

must live a life of ease, just wandering in the forest (Vitebsky field notes). Your kujjai

is like an animal double, and takes on the illness and misfortune which would otherwise

have hit you: thus when one mans kujjai was beaten, corresponding bruises appeared

on his own buttocks. When you are threatened by a serious danger, your kujjai stands

in front of you and takes the blow. When it dies, you may never know what the danger

was, but you can be sure that it gave its own life to save yours. You must then acquire

a new kujjai to keep up the same level of protection.

This seems a clear parallel to the wild animal that gives up its life to hunters so

that humans can continue living. But in becoming a personal bodyguard, the kujjai

takes a crucial further step. There is a general Eveny idea that one life-form can serve

as a substitute for another. Everyone tells stories of how a dog, horse, or even another

human has died in an accident or other misfortune as a substitute for someone else

(Vitebsky 2005: 275-8). But all these stories show that the animal and even the

human victim is a hapless, unconscious substitute (I cursed the Communist Party

Secretary, but his soul was too strong so it bounced off and killed someone else

instead). Only the kujjai knows what is going on, and deliberately takes the initiative

to offer itself.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

18 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

Figure 7. Eveny man travelling with saddle and sledge, December, at minus 60 celsius. When he

dies, one or more of the lead reindeer will be sacriced at his grave, to carry him into the next world.

(Photo by Piers Vitebsky.)

This is the richest form of the long-term relationship that Knight (2012: 343) talks

about between an animal and a human for whom it must die. But Knights argument

concerns a relationship between a human and livestock which has been bred for

submission. Rituals of the hunt try to mask the clash of interest between human and

animal but ultimately, we argue, they cannot square this circle. The kujjai solves this

impasse through its awareness, greater even than the awareness of its human partner, as

it (supposedly literally) sacrifices itself for that partners sake, of its own autonomous

volition. The kujjai fully harmonizes its own interests with that of its human partner.

It has sovereignty, but it is not brought into a human relationship kicking and screaming, like the semi-tamed bear. The sovereignty which in wild animals is manifested

through elusiveness, the inscrutability of Bayanay, or the rage of the caged bear is

transformed into the kujjais compassion and willingness to protect. The kujjais entire

life is a sacrifice waiting to happen, and the moment of its death is the culmination of

its human relationship and the realization of this destiny. The kujjais self-immolation

acts out a domesticated counterpart to the moment when a wild animal offers itself to

be killed, and is an even better enactment of that perfect hunt.

In utilitarian evolutionalist accounts, the riding deer was the first stage of ancient

domestication, a step which was taken for ecological or economic reasons. But the

kujjai has an equally plausible claim on cosmological grounds. The human domination of the mass herd is a by-product of the industrialization of herding under the

Russian empire and later the Soviet state farm. But this is exactly how these herders do

not see the saddled reindeer, and even less the kujjai. Rather, they invert Ingolds model

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 19

of the transition from trust to domination. The kujjai is hyper-domesticated, to a point

which makes it hard to call this a domination. The primal reindeer that sought domestication were offering humans a social contract, so that one could almost say it was the

reindeer who domesticated us. The trust between a herder and his kujjai is more sure

than that between a hunter and his prey. Rather than from trust to domination,

the progression is from unpredictability to reliability, and from evasiveness to trust.

Conclusion

In the shift from hunting to sacrifice, we propose the bear and the kujjai as alternatives

to the materialist form of ecologism and economism offered by more usual theories of

domestication, thus taking the hunters double bind seriously as a prime mover in the

development of new subsistence forms. Though we believe that these two cases can

shed light on the transition to the domestication of reindeer, these are not necessarily

to be understood as evolutionary stages in a single unilinear development. Rather,

they represent two possible routes, both of which are still active as current or recent

ritual modes of dealing with animals among groups of indigenous people in Northeast

Siberia. Their importance for history, ecology, and human-animal studies is that they

demonstrate how the domestication of the reindeer need not be simply an issue of

technological diffusion and ecological adaptation. It could equally well be a side-effect

of the playing out of tensions in the cosmology of hunting, a playing out which

originally served quite different ends than domestication, namely as a ritual means to

close the gap between words and deeds. Our theory also takes account of indigenous

rationales. Indigenous peoples, just like scientists, are very interested in origins. But

whereas scientists tend to generate materialist narratives, local people are also open to

spiritual explanations. We suggest that the natives may not be so wrong after all, even

in scientific terms.

NOTES

This article is the outcome of many years of research by each co-author. We are grateful to a wide range of

local informants and friends in the field, and to our respective institutions for long-term support.

1

Except for some Siberian domestic reindeer introduced to Alaska in 1891 (Jernsletten & Klokov 2002:

73-83).

2

Indigenous groups have various alternative names and spellings (Funk & Sillanp 1999). Eveny is a

Russianized plural of Even, who are distinct from the closely related Evenki.

3

Many communities have also moved in and out of an existence as hunters, after losing their reindeer

through raids or diseases (see Bogoras 1904-9: 618; Jochelson 1908: 434).

4

The term Siberia is generally used loosely for all of Russia east of the Urals. In this article we are

specifically concerned with the eastern end of this region (see Fig. 2), sometimes also called the Russian Far

East. In broader geographical terms, this is Northeast Asia.

5

The literature on the American North is filled with identical motifs about how animal prey must offer

itself freely to the hunter (e.g. Brightman 1993; Tanner 1979: 138; Walens 1981: 30). The Cree equate hunting

with compassion and lovemaking (Brightman 1993; Tanner 1979). Likewise, a Kwakiutl hunter, when he

dreams of copulating, immediately gets out of bed and goes hunting (Walens 1981: 132). The Naskapi hunter

sings for the caribou (Speck 1977 [1935]: 81) and the Naskapi, Montagnais, and Quebec-Labrador Cree used

to paint their caribou-skin coats with designs to please the caribou (Burnham 1992: 59). However, our

argument here concerns only Siberia, where the reindeer was domesticated, becoming a mainstay of most

indigenous cultures, and thereby opening up the issue of sacrifice alongside hunting.

6

Among numerous examples in the American North, the Rock Cree would similarly sing and drum to a

drawing of a moose to make the animal foolish so that hunters could kill it easily (Brightman 1993: 191).

They, too, likened sympathetic hunting magic to witchcraft and practised it with secrecy and fear (Brightman

1993: 192, 200).

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

20 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

7

We have consulted dictionaries of several indigenous languages in the Eurasian North, and though the

words are different, we have found the same situation in every one.

REFERENCES

Alekseyev, A. 1993. Zabyty mir predkov [The forgotten world of the ancestors]. Yakutsk: Sitim.

Anderson, D.G. 2002. Identity and ecology in Arctic Siberia: the number one reindeer brigade. Oxford:

University Press.

2004. Reindeer, caribou and fairy stories of state power. In Cultivating Arctic landscapes: knowing and

managing animals in the circumpolar North (eds) D.G. Anderson & M. Nuttall, 1-16. New York: Berghahn.

Batchelor, J. 1967 [1909]. The Ainu bear sacrifice. In From primitives to Zen: a thematic sourcebook on the

history of religions (ed.) M. Eliade, 206-11. London: Collins.

2013. Sympathetic magic of the Ainu: the native people of Japan. Unknown location: Pierides Press.

Bateson, G. 2000 [1972]. Steps to an ecology of mind. Chicago: University Press.

, D. Jackson, J. Haley & J. Weakland 1956. Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioural Science

1, 251-4.

Bird-David, N. 1992. Beyond the original affluent society: a culturalist reformulation. Current Anthropology

33, 25-47.

Bogoras, W. 1904-9. The Chukchee: Jesup North Pacific Expedition, vol. VII (American Museum of Natural

History Memoir 11). Leiden: E.J. Brill.

1924. New problems of ethnographical research in polar countries. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Americanists, 226-46. The Hague.

Bourdieu, P. 1994. Practical reason: on the theory of action (trans. R. Johnson). Cambridge: Polity.

Brightman, R. 1993. Grateful prey: rock Cree human-animal relationships. Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Burkert, W. 1972. Homo necans: the anthropology of ancient Greek sacrificial ritual and myth (trans. P. Bing).

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Burnham, D.K. 1992. To please the caribou. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Chaussonnet, V. 1988. Needles and animals: womens magic. In Crossroads of the continents: cultures of

Siberia and Alaska (eds) W. Fitzhugh & A. Crowell, 209-27. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1956. Nuer religion. Oxford: Clarendon.

Frazer, J. 1959 [1911]. The golden bough: a study in magic and religion (Abridged edition). London: Macmillan.

Funk, D. & L. Sillanp (eds) 1999. The small indigenous nations of northern Russia: a guide for researchers

(in English and Russian). Vaasa: bo Akademi University.

Hallowell, I. 1926. Bear ceremonialism in the northern hemisphere. American Anthropologist 28, 1-175.

Hatt, G. 1918. Rensdyrnomadismens elementer [The elements of reindeer nomadism]. Det Kongelige

Geografiske Selskab VII, 241-69.

Howell, S. 1996. Introduction. In For the sake of our future: sacrificing in eastern Indonesia (ed.) S. Howell,

1-26. Leiden: Research School CNWS.

Ingold, T. 1976. The Skolt Lapps today. Cambridge: University Press.

1980. Hunters, pastoralists and ranchers. Cambridge: University Press.

1986. Hunting, sacrifice and the domestication of animals. In The appropriation of nature: essays on

human ecology and social relations, 242-76. Manchester: University Press.

2000. From trust to domination: an alternative history of human-animal relations. In The perception

of the environment: essays in livelihood, dwelling and skill, 61-76. London: Routledge.

Jensen, A.E. 1963. Myth and culture among primitive peoples (trans. M.T. Choldin & W. Weissleder). Chicago:

University Press.

Jernsletten, J.L. & K. Klokov 2002. Sustainable reindeer husbandry. Troms: Centre for Saami Studies.

Jochelson, W. 1908. The Koryak (ed. F. Boas). New York: Memoir of the American Museum of Natural

History.

1926. The Yukaghir and the Yukaghirized Tungus (ed. F. Boas). New York: Memoir of the American

Museum of Natural History.

Jordan, P. 2003. Material culture and sacred landscape: the anthropology of the Siberian Khanty. Walnut Creek,

Calif.: AltaMira Press.

Kitagawa, J. 1961. Ainu bear festival (Iyomante). History of Religions 1, 95-151.

Knight, J. 2012. The anonymity of the hunt: a critique of hunting as sharing. Current Anthropology 53, 334-55.

Krupnik, I. 1993. Arctic adaptations: native whalers and reindeer herders of northern Eurasia. Hanover:

University Press of New England.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 21

Kwon, H. 1993. Maps and actions: nomadic and sedentary space in a Siberian reindeer farm. Ph.D. thesis,

University of Cambridge.

1998. The saddle and the sledge: hunting as comparative narrative in Siberia and beyond. Journal of

the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 4, 115-27.

Laufer, B. 1917. The reindeer and its domestication. Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association

4: 2, 91-147.

Leeds, A. 1965. Reindeer herding and Chukchi social institutions. In Man, culture and animals (eds) A. Leeds

& A. Vayda, 87-128. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Lissner, I. 1961. Man, god and magic. London: Jonathan Cape.

McKinnon, S. 1996. Hot death and the spirit of pigs: the sacrificial form of the hunt in Tanimbar Island. In

For the sake of our future: sacrificing in eastern Indonesia (ed.) S. Howell, 337-49. Leiden: Research School

CNWS.

Meuli, K. 1946. Griechische Opferbruche. In Phylobolia fr Peter von der Mhll, 185-288. Basel.

Paine, R. 1971. Animals as capital: comparisons among northern nomadic herders and hunters. Anthropological Quarterly 44, 157-72.

Paproth, H. & T. Obayashi 1966. Das Barenfest der Oroken auf Sachalin. Zeitschrift fr Ethnologie 91: Part

2, 211-36.

Pedersen, M.A. 2001. Totemism, animism and North Asian indigenous ontologies. Journal of the Royal

Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 7, 411-27.

Pedersen, M.A. & R. Willerslev 2012. The soul of the soul is the body: rethinking the concept of soul

through North Asian ethnography. Common Knowledge 18, 464-86.

Pomishin, S.B. 1990. Proiskhozhdenie olenevodstva i domestikatsiya severnogo olenya [The origin of reindeer

herding and the domestication of the reindeer]. Moscow: Nauka.

Rethmann, P. 2001. Tundra passages: history and gender in the Russian Far East. University Park: Pennsylvania

State University Press.

Seligman, B.Z. 1963. Appendix II: The bear ceremony. In Ainu creed and cult, N.G. Munro (ed. B.Z.

Seligman), 169-71. New York: Columbia University Press.

Shirokogoroff, S.M. 1935. The psychomental complex of the Tungus. Peking: Peking Press.

Shternberg, L.I. 1999 [1905]. The social organization of the Gilyak (ed. B. Grant) (Anthropological

Papers of the American Museum of Natural History). New York: American Museum of Natural

History.

Sirelius, U.T. 1916. ber die Art und Zeit der Zhmung des Renntiers. Journal de la Socit Finno-Ougrienne,

Helsinki 33: 2.

Skalon, V.N. 1956. Olennyye kamni Mongolii i problema proiskhozhdeniya olenevodstva [Reindeer

stones of Mongolia and the problem of the origin of reindeer herding]. Sovetskaya Arkheologiya 25,

87-105.

Smith, J.Z. 1987. The domestication of sacrifice. In Violent origins: Walter Burkert, Ren Girard, and Jonathan

Z. Smith on ritual killing and cultural formation (ed.) R.G. Hamerton-Kelly, 191-205. Stanford: University

Press.

1988. The bare facts of ritual. In Imagining religion: from Babylon to Jonestown, 53-65. Chicago:

University Press.

Speck, F.G. 1977 [1935]. Naskapi: savage hunters of the Labrador Peninsula. Norman: University of Oklahoma

Press.

Sverdrup, H.U. 1939. Among the tundra people (trans. M. Sverdrup). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tanner, A. 1979. Bringing home animals: religious ideology and mode of production of the Mistassini Cree

hunters. St Johns: Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Taussig, M. 1993. Mimesis and alterity: a particular history of the senses. New York: Routledge.

Vainshtein, S.I. 1980. Nomads of South Siberia: the pastoral economies of Tuva. Cambridge: University Press.

Valeri, V. 1994. Wild animals: hunting as sacrifice and sacrifice as hunting in Huaulu. History of Religion 34,

101-31.

Vasilevich, G.M. 1963. Early concepts about the universe among the Evenks. In Studies in Siberian shamanism (ed.) H.N. Michael, 46-83 (Arctic Institute of North America, Anthropology of the North, Translations

from Russian Sources 4). Toronto: University Press.

& M.G. Levin 1951. Tipy olenevodstva i ikh prioiskhozhdeniya [Types of reindeer herding and their

origins]. Sovetskaya Ethnografiya 1, 63-87.

& A.V. Smolyak 1956. The Evenks. In The peoples of Siberia (eds) M.G. Levin & L.P. Potapov, 620-54.

Chicago: University Press.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

22 Rane Willerslev

ET AL.

Vitebsky, P. 2005. Reindeer people: living with animals and spirits in Siberia. Boston: Houghton Mifflin;

London: HarperCollins.

Walens, S. 1981. Festing on cannibals: an essay on Kwakiutl cosmology. Princeton: University Press.

Watanabe, H. 1973. The Ainu ecosystem: environment and group structure. Seattle: University of Washington

Press.

Willerslev, R. 2001. The hunter as a human kind - hunting and shamanism among the Upper Kolyma

Yukaghirs. Journal of North Atlantic Studies 4, 44-50.

Willerslev, R. 2004a. Not animal, not not-animal: hunting, imitation, and empathetic knowledge among

the Siberian Yukaghirs. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 10, 629-52.

2004b. Spirits as ready to hand: a phenomenological study of Yukaghir spiritual knowledge and

dreaming. Anthropological Theory 4, 395-418.

2007. Soul hunters: hunting, animism and personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

2009. The optimal sacrifice: a study of voluntary death among the Siberian Chukchi. American

Ethnologist 36, 693-704.

2012. On the run in Siberia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

2013a. Rebirth and the death drive: rethinking Freuds Mourning and melancholia through a

Siberian time perspective. In Taming time, timing death: social technologies and ritual: Studies in death,

materiality and the origin of time, vol. 1 (eds) D. Refslund & R. Willerslev, 79-98. London: Ashgate.

2013b. God on trial: human sacrifice, trickery, and faith. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3: 1,

140-54.

& M.A. Pederson 2010. Proportional holism: joking the cosmos into the right shape in North Asia.

In Experiments in holism: theory and practice in contemporary anthropology (eds) T. Otto & N.O. Bubandt,

262-78. Oxford: Blackwell.

& O. Ulturgasheva 2012. Revisiting the animism versus totemism debate: fabricating persons

among the Eveny and the Chukchi of north-eastern Siberia. In Animism in rainforest and tundra: personhood, animals, plants and things in contemporary Amazonia and Siberia (eds) M. Brightman, V.E. Grotti &

O. Ulturgasheva, 48-68. New York: Berghahn.

Zeuner, F.E. 1963. The Pleistocene period: its climate, chronology and faunal successions. London: The Ray

Society.

Du sacrice comme chasse idalise : une explication cosmologique de la

domestication du renne

Rsum

Il existe entre la cosmologie des peuples de chasseurs et celle des leveurs de rennes du Nord-est de la

Sibrie des parallles frappants, dans lesquels on peut trouver quelques indices relatifs au passage de la

chasse au pastoralisme. Les auteurs avancent lide quil y a une identit structurelle entre chasse et sacrifice

et que le renne a t domestiqu par des chasseurs tentant de matriser les alas de la chasse au moyen du

sacrifice. Les chasseurs ne peuvent mettre en pratique leur thos de la confiance avec la proie que dans

le cadre dactes rituels strictement contrls. Nous en dcrivons deux : la clbre fte de lours dans la

rgion de la baie de lAmour, et le renne sacr des vnes. Ces deux rituels expriment la mme logique

densemble : celle du sacrifice fonctionnant comme une chasse idale. Lanimal est impliqu dans une

relation non pas de domination mais de confiance, tout en subissant un processus dapprivoisement.

Nous suggrons, par consquent, que la domestication du renne na pas t motive seulement par des

adaptations cologiques ou conomiques, mais aussi par la cosmologie.

Rane Willerslev is Professor of Anthropology and Fellow of the Arctic Research Center and Aarhus Institute

of Advanced Studies, Aarhus University. He is the author of Soul hunters: hunting, animism, and personhood

among the Siberian Yukaghirs (University of California Press, 2007) and On the run in Siberia (University of

Minnesota Press, 2012).

Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies, Buildings 1630-1632, Hegh Guldbergs Gade 6B, DK-8000 Aarhus C,

Denmark. rane@mail.dk

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) , -

Royal Anthropological Institute 2014

Sacrifice as the ideal hunt 23

Piers Vitebsky is Head of Anthropology at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge. He is the author

of Reindeer people: living with animals and spirits in Siberia (Houghton Mifflin/HarperCollins, 2005) and

Dialogues with the dead: the discussion of mortality among the Sora of eastern India (Cambridge University

Press, 1993).

Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge CB2 1ER, UK. pv100@

cam.ac.uk