Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Edu5ldp Ilp Analysis

Transféré par

api-279746002Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Edu5ldp Ilp Analysis

Transféré par

api-279746002Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

EDU5LPD Assignment 1: Case Study

1. Student Profile

Socio-demographic profile

Sophie is 9 years old and attends Year 3 at a Catholic primary school in a small regional town

in Victoria. The school has 125 students, organised into six multi-age classes. Sophie is in a

class of 18 students (10 in Year 2, and 8 in Year 3). While Sophie is the only child in the class

with dyslexia, two other children have mild-ASD (diagnosed) and one child recently suffered a

major trauma due to death of a parent. Being a small school, there is a high degree of

involvement from the parents in the classroom.

Sophie has a stable home environment with significant parental support. Sophie has an 11-yearold and 6-year-old brother, both of whom are highly achieving academically. There are

concerns of comparison with her brothers; however there appears to be no identifiable affect on

Sophies sense of identity to date. While Sophies cultural background is Italian on the paternal

side of her family, the family is predominantly uni-lingual and English has always been the

only language spoken at home.

Reports from the Maternal and Child Health Nurse indicate that Sophie has demonstrated no

known developmental delays in physical or cognitive areas. While she is in the 30th percentile

for height, she is also only in the 20th percentile for weight meaning that her physical

development (while small) is proportionate and does not indicate any concern. Sophies speech

development, as assessed by her Speech Pathologist, indicates that she met all major milestones

and has always has an appropriate size of vocabulary and use of sounds and words in speech.

Sophie is a very happy, social and well-adjusted child at school, and she is very well-liked by

her peers. Sophie has not demonstrated the typical development of emotional problems that

students with dyslexia experience when early reading instruction does not match their learning

needs.

Learning Profile

Sophie has been assessed by a Speech Pathologist with moderate dyslexia at 8 years of age (6

months ago). Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurological in origin. It is

characterised by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling

and decoding abilities (Clark & Uhry, 1995; Dykman & Ackerman, 1992; MacKay, 2004). It is

referred to as a learning disability because dyslexia can make it very difficult for a student to

succeed academically in the typical instructional environment (Reid, 2013).

Specifically, Sophies form of dyslexia was assessed by her Speech pathologist as residing in a

reduced capacity of the working memory function. Drawing on Baddeley and Hitchs (1974)

model, working memory has two systems: the phonological loop retains material in a

phonological code that is highly susceptible to time-based decay, and the visuospatial

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

sketchpad has limited capacities to represent information in terms of its visual and spatial

characteristics.

Working memory is known to be linked with reading ability. Gathercole, Alloway, Willis, and

Adams (2006) findings suggest that working memory skills represent an important constraint

on the development of skill and knowledge in reading. In typically developing samples of

children, scores on complex memory tasks predict reading achievement independently of

measures of phonological short term memory (Siegel & Ryan, 1989; Swanson, 1994, 2003;

Swanson, Ashbaker, & Lee, 1996; Swanson & Howell, 2001). For Sophie, the key presentation

is in very poor spelling and writing functions, and below average reading ability. Sophie also

has difficulties recalling sequential instructions when given verbally.

While students with dyslexia often end up feeling less capable than they actually are, Sophie

has many strengths that she has developed naturally to compensate for her dyslexia (Singer,

2005). Her artistic abilities are well-developed, and she often demonstrates creative solutions to

problems. Her sociability and creativity also allows her to articulate ideas well when spoken.

Sophie also relies heavily on her social skills to help her solve problems in class and aid her in

following teacher instructions when she has not understood. Sophie has high aspirations for her

education, and her enjoyment of artistic and creative pursuits have lead her to indicate that this

is a path she would like to follow in later years of schooling; she has indicated that she would

like to be an architect as she likes drawing and designing.

Support factors

The Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cwlth) and the Disability Standards for Education

2005 (Cwlth) requires adjustments to teaching and learning experiences and assessment tasks to

enable a student to demonstrate their knowledge, skills or competencies. To comply with these

standards I would consult with the student and parent as part of the process to personalise

learning and adjustment reviews occur regularly, and are changed or withdrawn where

necessary. It is also important that all teachers across the curriculum will deploy a range of

strategies & resources designed to ensure that the curriculum content is appropriate to Sophies

level of understanding and interest. The ILP specifically provides a statement of purpose

designed to embed these critical factors.

Sophie has a stable home environment with significant parental support. Sophies parents had

early concerns during 4-year-old Kindergarten that she was not as articulate as her older

brother, however these concerns were dismissed by the educator and attributed to overly

anxious parenting and unfair sibling comparisons. Based on this negative experience, Sophies

parents were reluctant to voice concerns that arose later in the early years of primary school,

and this was compounded when Sophie was not identified for reading Recovery in Year 1.

However, the school and parents concerns emerged by Year 2, and as a result Sophies parents

sought the help of a Speech Pathologist who confirmed an assessment of moderate dyslexia

with specific focus on working memory function. The result of this process has been a

willingness to provide support and be involved with Sophies education, yet at the same time a

degree of mistrust due to missed opportunities for earlier intervention.

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

2. Inclusive Strategies

Based on the work of Foreman (2008) and (Kelly & Lyons, 2008) successful inclusion is

contingent upon the active engagement and support of the school community, the provision of a

facilitative learning environment and the best quality teaching. Using this multivariate

approach, inclusive strategies therefore must be orientated to include the curriculum, the

classroom, the teacher and the school and macro level environment.

Curriculum & Assessment

Research suggests that learning activities in literacy classes often impose heavy demands on

working memory, resulting in frequent task failures in children with poor working memory

function. (Gathercole et al., 2006). As teachers will have the freedom to adapt class work,

homework, marking and assessments to fit the needs of the child within the supportive school

environment, several adaptions to the curriculum are possible. An assessment and plan

(provided with ILP) have been undertaken and shared by her Speech Pathologist, with whom

she attends sessions for 1 hour per week. This plan provides specific information for the

teaching of phonic awareness and letter identification, and forms the basis to help with

Sophies spelling. Sophie is also involved in the Year 3 Reading Recovery program each day

for 30 minutes of individual tuition. This is supported at home with an individual home reading

program.

While it is recognised that standardised testing may not be appropriate for dyslexic learners

(Reid, 2012), NAPLAN remains an important part of formal assessment. However, it is also

understood that classroom teachers will be best placed to decide which assessments are most

appropriate for Sophie and where possible alternative methods for recording work are used,

such as mind maps, story boards, flow charts, bullet points, power points, and oral

presentations. Differentiated writing tasks help to take into account that Sophie is verbally able

but has difficulty in recording, and this includes providing more time for assessment tasks.

Reinforcing positive self-identity is important for students with dyslexia, and therefore marking

for success is applied. This involves the use of highlighter marking at a ratio of 3 success

criteria met to 1 next step learning prompt.

Classroom routines & resources

Gathercole et al. (2006) predict that promoting teacher awareness of working memory loads in

classroom activities, and effective management of these loads for children with impairments of

working memory, should boost their learning. There exist a number of methods for reducing

working memory loads that could readily be applied to classroom practice.

It is critical for Sophie that verbal instructions are clear and concise, and where she does not

understand, she is encouraged to consult with her buddy. When Sophie does ask for help or

clarification, she is thanked to positively reinforce that practise, even when she has not been

listening. Sophie is regularly asked to repeat and explain in her own words what they have to

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

do. To help further, learning intentions are repeated throughout the lessons, and a large

illustrated timetable is available in classroom.

Resource organisation is also critical to aiding Sophies learning. Access to equipment must be

well organised, clearly labelled and rehearsed. Examples of resources include: resources are

available of numbers 1-100, place value charts, days of the week, months of the year for Sophie

to access independently; a written and numerical example of the date is provided every day and

Sophie writes the date on at least one piece of work a day; and key topic words are displayed

and Sophie has access to word banks. Where possible, the benefits of technology can be

applied in the classroom as an alternative means of recording work. Where more traditional

means of teacher resources are used, Comic sans or Arial font, size 12 minimum is used, with

bold rather than underlining for key words, ideas and titles.

Role of the teacher

Research highlights the central role of teacher expectations in teaching students with dyslexia,

who were found to receive lower teacher ratings of writing achievement from their teachers

when their teacher held a more negative implicit attitude toward dyslexia. (Hornstra, Denessen,

Bakker, van den Bergh, & Voeten, 2010 p. 525) At the most basic level, it is important to the

language of success and possibility at all times, including positive language which is specific

eg: Make sure you change Y to ies at the end of these words rather than Dont forget to

. This will also reinforce Sophies positive identity and avoid esteem issues for as long as

possible (Humphrey, 2002, 2003).

Additionally, it is important that the school raises staff awareness and takes advantage of any

Professional Development opportunities to increase knowledge of best practice in meeting the

learning needs of children with dyslexia (Lewis & Norwich, 2004; MacKay, 2004; Richardson,

1996). Additionally, staff should be provided with particular guidance in relation to dyslexia

awareness so that they are well positioned to identify difficulties of a dyslexic nature,

understand the needs of dyslexic students and help them to learn more effectively.

Macro level factors

There has been a long history in speech and language therapy of working collaboratively with

parents (Bowen & Cupples, 2004), and as a result of technological developments in accessing

information, many parents now present with their children expecting to be team members in

developing individual learning plans and to engage collaboratively and cooperatively in

assessment and therapy (McWilliam, McWilliam, Winton, & Crais, 1996). Sophies parents

have made it clear to the school that they are willing partners in Sophies ongoing education

and needs.

It is also critical for the school to develop links with outside agencies (Berninger, 2001; Reid,

2013; Uhry & Clark, 2005), such as SPELD, to ensure consistency in a childs learning when

they receive additional support outside of school. The school can also draw on advice from the

range of support services available within the area. Access to specialist services can help the

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

school to achieve a better understanding of the factors that may be helping or hindering

progress and to identify ways forward.

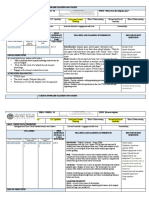

3. Individual Learning Plan1

SECTION 1: STUDENT DETAILS

Student Name: SOPHIE

Date of Birth: September 2006

School: Year 3, Catholic Primary School, VIC

School Contact Person: Classroom teacher

Date of Plan: 1 JULY 2015

Review Date: 14 SEPTEMBER 2014 (END OF TERM 3)

1.1 Plain English Description of the Issue:

Sophie is a Year 3 student with moderate dyslexia. The key to Sophies dyslexia lies in the working

memory function, which is not functioning at an age appropriate level, and she is not able to hold the

information for long enough in order to then apply what is required to the task at hand. This often

presents as though she does not understand the material or cant keep up. For Sophie, the key

presentation is in very poor spelling function and difficulty recalling sequential instructions.

1.2 Statement of Purpose

Each student with dyslexia should have access a positive and inclusive teaching environment that is

informed by current practice. Teaching staff should be knowledgeable of the unique nature of each

students specific learning needs and they should be familiar with the diverse pedagogical

competencies associated with the effective management of the educational needs of students with

dyslexia. Students will be provided with a relevant curriculum which is differentiated by presentation,

pace, level and outcome to meet their individual needs; this will include materials and tasks tailored

to suit their particular learning profile.

1.3 Student Support Group Membership:

School-based

Agency

Classroom teacher

Private Speech Pathologist

School Principal

Reading Recovery program teacher

School Learning Support advisor

Community

Classroom teacher aid

Parents Mother, father.

Note: Some of the information contained in the ILP for Sophie duplicates that which is contained in the case study.

This is important for the purposes of completeness, as the ILP would typically intended to be a stand-alone

document and may not necessarily be read or completed in conjunction with any other information.

2

This information in these Appendices would be included in the standalone ILP, and provide a comprehensive

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

1.4 Services/Agencies (Workers currently involved with the student):

Worker

Details

Involvement

Private Speech

Pathologist

Undertakes clinical speech pathology therapy

with Sophie focussing on a plan of treatment

for dyslexia.

1 hour session per week.

Started at the beginning of

Term 1 2015.

Speech Pathology Inc.

Contact details

Ph: xxxx-xxx-xxx

Reading Recovery

program teacher

6 months/ 2 school terms.

To undertake one on one session with Sophie

within the reading recovery program

structure.

Within school, out of classroom.

Reading Recovery

Contact details

Ph: xxxx-xxx-xxx

30mins per day x 5 days per

week

6 months/ 2 school terms.

Started at the beginning of

Term 1 2015.

SECTION 2: UNDERSTANDING THE STUDENT

2.1 Students skills, strengths, preferences, abilities and motivations:

Sophie has many strengths that she has developed naturally to compensate for her dyslexia.

Her artistic abilities are well-developed, and she often demonstrates creative solutions to

problems. Her sociability and creativity also allows her to articulate ideas well when spoken.

Sophie also relies heavily on her social skills to help her solve problems in class and aid her in

following teacher instructions when she has not understood.

2.2 Academic progress general remarks re overall strengths and areas for development:

The key to Sophies dyslexia lies in the working memory function, which is not functioning at

an age appropriate level, and she is not able to hold the information for long enough in order

to then apply what is required to the task at hand. This often presents as though she does not

understand the material or cant keep up.

For Sophie, the key presentation is in very poor spelling and writing functions. Sophie also has

difficulties recalling sequential instructions when given verbally.

2.3 Social skills and relationships

Sophie is a very happy, social and well-adjusted child at school, and she is very well liked by

her peers.

2.4 Attendance and Engagement

Sophie has a stable home environment with significant parental support. Sophie has an 11year-old and 6-year-old brother, both of whom are highly achieving academically.

2.5 Supporting Documents (Provided with this ILP; to be linked electronically)

Speech Pathology report;

Detailed case study materials

School records (Prep-3) & NAPLAN results Year 3 2015

Reading Recovery Progress reports

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

SECTION 3: DETAILED LEARNING GOALS

As Sophies dyslexia was diagnosed late, is important that remedial work continues where possible,

but the focus remains on enhancing her strengths and developing coping mechanisms to find

alternatives for her learning abilities. Therefore the goal selected focus primarily on enhancing her

strengths (Goals 1 & 2), with only one goal focussed solely on remedial work (Goal 3). The goals

selected reflect the Australian Curriculum English Content descriptors for Year 3 (see Appendix 2).

Goal 1:

Improve working memory through discussion-based activities.

Activity:

Listen to and contribute to conversations and discussions to share

information and ideas and negotiate in collaborative situations

(ACELY1676)

Strengths Related to

Goal:

Sophie is a very social child and finds it easy to interact with her

peers.

She enjoys classroom and small group discussions.

Barriers to Achieving

Goal:

Sophie needs to use her working memory to be able to keep pace

with the interactions and hold the information throughout the

exercises.

This will be challenging for Sophie, especially when the information

is sequential in nature.

Strategies to Achieve

Goal:

Sophie will need to be guided in using memory approaches, such as

building sequential memory, jotting down clues to help remind her

(may be pictures, or words)

Actions & Time-Line:

Assess Sophie at the start of Term 3 to benchmark her current

abilities to recall information from a discussion.

Reassess every 2 weeks during the class activity.

By the end of Term 4 Sophie should be able to accurately recall 50%

of the details presented in the activity.

Goal 2:

Enhance creativity in literature

Activity:

Create imaginative texts based on characters, settings and events

from students own and other cultures using visual features, for

example perspective, distance and angle (ACELT1601)

Strengths Related to

Goal:

Sophie enjoys activities involving imagination and creativity,

especially where artistic elements can be included.

Barriers to Achieving

Goal:

Sophie is often discouraged by text-based activities, as she finds

starting the task overwhelming.

She often focuses too much on the mechanical use of the text and

the barrier of getting her spelling correct, rather than the

imaginative aspects of creating literature.

Strategies to Achieve

Goal:

Focus on allowing Sophie to develop imaginative texts by first using

non-word based methods, such as drawing or verbal discussion.

This approach will start the activity on a positive note for Sophie,

and she will engage immediately rather than find it overwhelming to

start writing straight away.

Sophie can then translate her initial work into a text-based activity

with the guided help of the teacher, other students in a small group,

or the Teacher Aid.

Debra da Silva

Actions & Time-Line:

SID #18252191

Assess Sophie at the start of Term 3 to benchmark her current

abilities to create an imaginative text.

Reassess every 2 weeks during the class activity.

By the end of Term 4 Sophie should be able to start the activity

using pictures and verbal discussion, and then transition this into a

text-based structure with limited guidance.

Goal 3:

Improve phonetics and phonology

Activity:

Understand how to use soundletter relationships and knowledge of

spelling rules, compound words, prefixes, suffixes, morphemes and

less common letter combinations, for example tion (ACELA1485)

Strengths Related to

Goal:

Sophie is willing to work hard in studying for spelling tests, and has

demonstrated that she is keen to improve.

She is not yet discouraged with her progress and the approach

employed should be very mindful not to create any discouragement.

Barriers to Achieving

Goal:

Sophies working memory function of phonological concepts is poor.

Strategies to Achieve

Goal:

Explicit one to one instruction is needed to progress in this area, and

small group work within the class is not productive for Sophie.

The Teacher Aid will work with Sophie for 15 mins each day during

the literacy lesson to progress this.

Actions & Time-Line:

Assess Sophie at the start of Term 3 to benchmark her current

abilities with a verbal and written test of 10 common words with

prefixes and suffixes.

Reassess every 2 weeks during the class activity.

By the end of Term 4 Sophie should be able to complete a test of 20

common words with suffixes and prefixes with an accuracy of

>60%.

Goal 4:

Pastoral support so as to provide opportunities to discuss anxieties and improve selfesteem.

Activity:

Classroom teacher and the principal to check-in with Sophie,

independently, and on a casual basis (eg, in the playground) to

ensure that she is coping with the increased focus on her dyslexia

and the additional activities in he classroom.

Strengths Related to

Goal:

Sophie does not currently present any issues related to self-esteem

or identity.

Barriers to Achieving

Goal:

No known barriers.

Strategies to Achieve

Goal:

Informal monitoring Sophies progress over the course of the term in

all areas, to ensure that she maintains a positive identity, and does

not present any issues either in the classroom or with peers.

Actions & Time-Line:

Discussion with parents at throughout the term to ensure that no

issues have arisen in this area.

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

SECTION 4: REVIEW PROCESS

4.1 Data and information to be gathered

Updated and revised clinical assessment from Speech Pathologist at the end of Term 4.

Four Reading Recovery progress reports and assessments (at the end of week 4 in both Terms

3 and 4, and at the end of Terms 3 and 4). This will allow minor adjustments to be made as

needed. It is also encouraged to have discussion with the Reading Recovery teacher on an

ongoing basis to account for any issues that arise on a day to day and week to week basis.

In accordance with the Speech Pathologists request, I will undertake small tests to assess

Sophies working memory function each week on a Tuesday morning. The results of this will be

tracked over Term 3 and 4, and the results will be summarised and shared with the team.

4.2 Consultation process

Sophies parents are to be closely involved in the ILP process. It is recommended that the

teacher checks in with Sophies mother as she regularly attends school for pick up on

Wednesday-Friday. This relationship building will help facilitate the process and build support

between home and school. Sophies parents have also indicated that they are willing to be

contacted directly by phone should the need arise to discuss any issues.

Speech Pathologist to receive a copy of Sophies progress at the end of Term 4 in order to

provide written and verbal feedback and input. The Speech Pathologist will also provide a

revised plan with updated information on Sophies clinical results at this time.

4.3 Revision of ILP

A formal review of this ILP will take place at the end of Terms 3 and 4, as well as at the start

of the 2016 school year. (See attached schedule).

It is critical that there is a seamless transition between the 2015 and 2016 school years for

Sophie. The lack of remedial action to date has been a hindrance, and we do not want any

further time to be lost due to administrative inefficiencies. The 2016 classroom teacher will be

involved in the end of Term 4 review process, and the Reading Recovery teacher will continue

with Sophie next year.

Additionally, Sophies parents will be contacted prior to the start of the school year in 2016 to

discuss any significant changes/issues that may have occurred over the summer break, so that

they can be accounted for prior to the school year.

SECTION 5: AGREEMENT

Review 1:

End of Term 3

Review 2:

End of Term 4

Parent

Classroom Teacher (2015)

Classroom Teacher (2016)

Learning Support Advisor

Speech Pathologist

Reading Recovery Teacher

School Principal

Review 3:

Start of Term 1

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

4. Reflections and Conclusions

The usefulness of an ILP rests in the extent to which it is appropriately developed and

implemented. There were several key limitations that I identified in searching for an ILP for

Sophie. A litmus test that I applied was if I had no knowledge of this student, and was required to

teach her, would I be able to modify my teaching appropriately based on the information

contained in this ILP, assuming that it would not typically be accompanied by a detailed case

study?

Many of the plans lacked sufficient detail that would enable me to codify, access and share

information. It was important that I modified the ILP so that relevant and important documents

(such as the assessment from the Speech Pathologist) were embedded (hyperlinked on the intranet)

so that information set was complete. This also ensures that Sophies parents do not have to

repeatedly provide documents that should be accessible by all members of Sophies learning

support team.

Another key element of the ILP was to embed the consultation process to enable best practise. Too

often consultation is an ideal, rather than an embedded practise with set goals and documented

outcomes. Following on from this, there needs to be a specific review process with pre-identified

data collection for measurable outcomes.

The end result of this is that the ILP expands to be more comprehensive than many of the

templates available. The requisite work to complete the ILP therefore expands as well. However,

this ensures that the ILP for Sophie is comprehensive, supported by easy access to essential

information, shared among the learning support team, embeds consultation and reviews processes,

and reduces the administrative burden on Sophies parents. While the inputs require more work,

the outcomes better achieve the inclusive practises that teachers and parents indicate they desire

for the child.

5. References

Antoniazzi, D., Snow, P., & Dickson-Swift, V. (2010). Teacher identification of children at risk

for language impairment in the first year of school. International journal of speechlanguage pathology, 12(3), 244-252.

Baddeley, A. (1996). Exploring the central executive. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Section A, 49(1), 5-28.

Baddeley, A. (2000). The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory? Trends in

cognitive sciences, 4(11), 417-423.

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nature reviews

neuroscience, 4(10), 829-839.

Baddeley, A., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. The psychology of learning and motivation,

8, 47-89.

Barrow, R. (2001). Inclusion vs. fairness. Journal of Moral Education, 30(3), 235-242.

10

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

Berninger, V. W. (2001). Understanding the lexiain dyslexia: A multidisciplinary team

approach to learning disabilities. Annals of dyslexia, 51(1), 21-48.

Boder, E. (1973). Developmental dyslexia: A diagnostic approach based on three atypical

reading-spelling patterns. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 15(5), 663-687.

Bowen, C., & Cupples, L. (2004). The role of families in optimizing phonological therapy

outcomes. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 20(3), 245-260.

Brady, S., & Moats, L. (1997). Informed Instruction for Reading Success: Foundations for

Teacher Preparation. A Position Paper of the International Dyslexia Association.

Clark, D. B., & Uhry, J. K. (1995). Dyslexia: Theory & practice of remedial instruction: York

Press.

Daneman, M., & Carpenter, P. A. (1980). Individual differences in working memory and

reading. Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 19(4), 450-466.

Dykman, R. A., & Ackerman, P. T. (1992). Diagnosing dyslexia: IQ regression plus cut-points.

Journal of Learning Disabilities.

Exley, S. (2003). The effectiveness of teaching strategies for students with dyslexia based on

their preferred learning styles. British Journal of Special Education, 30(4), 213-220.

Foreman, P. (2008). Inclusion in action: Cengage Learning Australia.

Foreman, P., Arthur-Kelly, M., Pascoe, S., & King, B. S. (2004). Evaluating the educational

experiences of students with profound and multiple disabilities in inclusive and

segregated classroom settings: An Australian perspective. Research and Practice for

Persons with Severe Disabilities, 29(3), 183-193.

Foreman, P., & Arthur-Kelly, M. (2008). Social justice principles, the law and research, as bases

for inclusion. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 32(1), 109-124.

Forlin, C. (2001). Inclusion: Identifying potential stressors for regular class teachers.

Educational Research, 43(3), 235-245.

Gathercole, S. E., Alloway, T. P., Willis, C., & Adams, A.-M. (2006). Working memory in

children with reading disabilities. Journal of experimental child psychology, 93(3), 265281.

Gersten, R., Baker, S. K., Haager, D., & Graves, A. W. (2005). Exploring The Role of Teacher

Quality in Predicting Reading Outcomes for First-Grade English Learners An

Observational Study. Remedial and special education, 26(4), 197-206.

Groom, B., & Rose, R. (2005). Supporting the inclusion of pupils with social, emotional and

behavioural difficulties in the primary school: the role of teaching assistants. Journal of

Research in Special Educational Needs, 5(1), 20-30.

Henry, M. K. (1997). The decoding/spelling curriculum: integrated decoding and spelling

instruction from pre-school to early secondary school. Dyslexia, 3(3), 178-189.

11

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

Hines, R. A. (2001). Inclusion in middle schools: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early

Childhood Education, University of Illinois.

Hornstra, L., Denessen, E., Bakker, J., van den Bergh, L., & Voeten, M. (2010). Teacher

attitudes toward dyslexia: Effects on teacher expectations and the academic achievement

of students with dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities.

Humphrey, N. (2002). Teacher and pupil ratings of self-esteem in developmental dyslexia.

British Journal of Special Education, 29(1), 29-36.

Humphrey, N. (2003). Facilitating a positive sense of self in pupils with dyslexia: the role of

teachers and peers. Support for Learning, 18(3), 130-136.

Hwang, Y.-S., & Evans, D. (2011). Attitudes towards inclusion: gaps between belief and

practice. International journal of special education, 26(1), 136-146.

Jeffries, S., & Everatt, J. (2004). Working memory: its role in dyslexia and other specific

learning difficulties. Dyslexia, 10(3), 196-214.

Kelly, A., & Lyons, G. (2008). Practising Successful Inclusion. In P. Foreman (Ed.), Inclusiuon

in Action (pp. 70-111): Cengage Learning Australia.

Kiuru, N., Aunola, K., Torppa, M., Lerkkanen, M.-K., Poikkeus, A.-M., Niemi, P., . . . Tolvanen,

A. (2012). The role of parenting styles and teacher interactional styles in children's

reading and spelling development. Journal of school psychology, 50(6), 799-823.

Lerkkanen*, M.-k., Rasku-Puttonen, H., Aunola, K., & Nurmi, J.-e. (2004). Predicting reading

performance during the first and the second year of primary school. British Educational

Research Journal, 30(1), 67-92.

Lewis, A., & Norwich, B. (2004). Special Teaching For Special Children? Pedagogies For

Inclusion: A Pedagogy for Inclusion? : McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

MacKay, N. (2004). The case for dyslexia-friendly schools. Dyslexia in Context: Research,

Policy and Practice, 223-236.

Matthews, N. (2009). Teaching the invisibledisabled students in the classroom: disclosure,

inclusion and the social model of disability. Teaching in higher education, 14(3), 229239.

McWilliam, P., McWilliam, P., Winton, P., & Crais, E. (1996). Family-centered practices in

early intervention. Practical strategies for family-centered intervention. San Diego:

Singular Publishing Group, Inc.

Overy, K. (2000). Dyslexia, temporal processing and music: The potential of music as an early

learning aid for dyslexic children. Psychology of Music, 28(2), 218-229.

Peer, L., & Reid, G. (2001). Dyslexia: Successful inclusion in the secondary school: Routledge.

Reid, G. (2012). Dyslexia and inclusion: Classroom approaches for assessment, teaching and

learning: Routledge.

Reid, G. (2013). Dyslexia: A practitioner's handbook: John Wiley & Sons.

12

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

Richardson, S. O. (1996). Coping with dyslexia in the regular classroom: Inclusion or exclusion.

Annals of dyslexia, 46(1), 37-48.

Riddick, B. (2001). Dyslexia and inclusion: time for a social model of disability perspective?

International studies in sociology of education, 11(3), 223-236.

Rose, J. (2009). Identifying and teaching children and young people with dyslexia and literacy

difficulties: an independent report.

Shaywitz, S. E. (1998). Dyslexia. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(5), 307-312.

Siegel, L. S., & Ryan, E. B. (1989). The development of working memory in normally achieving

and subtypes of learning disabled children. Child development, 973-980.

Singer, E. (2005). The strategies adopted by Dutch children with dyslexia to maintain their selfesteem when teased at school. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(5), 411-423.

Snowling, M. J. (1981). Phonemic deficits in developmental dyslexia. Psychological research,

43(2), 219-234.

Snowling, M. J., Duff, F., Petrou, A., Schiffeldrin, J., & Bailey, A. M. (2011). Identification of

children at risk of dyslexia: the validity of teacher judgements using Phonic Phases.

Journal of Research in Reading, 34(2), 157-170.

Swanson, H. L. (1994). Short-Term Memory and Working Memory Do Both Contribute to Our

Understanding of Academic Achievement in Children and Adults with Learning

Disabilities? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27(1), 34-50.

Swanson, H. L. (2003). Age-related differences in learning disabled and skilled readers working

memory. Journal of experimental child psychology, 85(1), 1-31.

Swanson, H. L., Ashbaker, M. H., & Lee, C. (1996). Learning-disabled readers' working

memory as a function of processing demands. Journal of experimental child psychology,

61(3), 242-275.

Swanson, H. L., & Howell, M. (2001). Working memory, short-term memory, and speech rate as

predictors of children's reading performance at different ages. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 93(4), 720.

Tzouveli, P., Schmidt, A., Schneider, M., Symvonis, A., & Kollias, S. (2008). Adaptive reading

assistance for the inclusion of students with dyslexia: The AGENT-DYSL approach.

Paper presented at the Advanced Learning Technologies, 2008. ICALT'08. Eighth IEEE

International Conference on.

Uhry, J. K., & Clark, D. B. (2005). Dyslexia: Theory & practice of instruction: Pro Ed.

Wadlington, E. M., & Wadlington, P. L. (2005). What educators really believe about dyslexia.

Reading Improvement, 42(1), 16-33.

(Antoniazzi, Snow, & Dickson-Swift, 2010; Baddeley, 1996, 2000, 2003; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Barrow, 2001; Berninger, 2001; Boder, 1973; Bowen & Cupples, 2004; Brady & Moats, 1997; Clark & Uhry, 1995; Daneman & Carpenter, 1980; Dykman & Ackerman, 1992; Exley, 2003; Foreman, 2008; Foreman, Arthur-Kelly, Pascoe, & King, 2004; Foreman & Arthur- Kelly, 2008; Forlin, 2001; Gathercole et al., 2006; Gersten, Baker, Haager, & Graves, 2005; Groom & Rose, 2005; Henry, 1997; Hines, 2001; Hornstra et al., 2010; Humphrey, 2002, 2003; Hwang & Evans, 2011; Jeffries & Everatt, 2004; Kiuru et al., 2012; Lerkkanen*, Rasku-Puttonen, Aunola, & Nurmi, 2004; Lewis & Norwich, 2004; MacKay, 2004; Matthews, 2009; McWilliam et al., 1996; Overy, 2000; Peer & Reid, 2001; Reid, 2012, 2013; Richardson, 1996; Riddick,

2001; Rose, 2009; Shaywitz, 1998; Siegel & Ryan, 1989; Singer, 2005; Snowling, 1981; Snowling, Duff, Petrou, Schiffeldrin, & Bailey, 2011; Swanson, 1994, 2003; Swanson et al., 1996; Swanson & Howell, 2001; Tzouveli, Schmidt, Schneider, Symvonis, & Kollias, 2008; Uhry & Clark, 2005; Wadlington & Wadlington, 2005)

13

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

APPENDIX 1: WHAT IS DYSLEXIA?2

From the International Dyslexia Association www.interdys.org

Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurological in origin. It is

characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor

spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the

phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other

cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary

consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading

experience that can impede the growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.

From http://www.speldvic.org.au/information/for-teachers:

Dyslexia is often referred to as a hidden disability and is defined as an unexpected

difficulty in reading in comparison to ones intelligence. Although dyslexia varies from

person to person, common characteristics among people with dyslexia are difficulty

with spelling, phonological processing (the manipulation of sounds), numeracy and/or

auditory short term memory.

Characteristic features of dyslexia are:

o

Phonological awareness is defined as the ability to identify and manipulate

the sounds in words, and is recognised as a key foundation skill for early

word-level reading and spelling development. For example, phonological

awareness would be demonstrated by understanding that if the p in pat is

changed to an s, the word becomes sat.

Verbal (phonological short-term) memory is the ability to retain an

ordered sequence of verbal material for a short period of time. It is used, for

example, to recall a list of words or numbers or to remember a list of

instructions.

Verbal processing speed is the time taken to process familiar verbal

information, such as letters and digits. Difficulties in these areas can be

thought of as reflecting disorders in the systems that are involved in

processing information about word sounds (phonology).

Further Information:

http://www.speldvic.org.au/information/dyslexia-and-ld

http://www.dyslexia-australia.com.au

http://www.dyslexia.org.au

This information in these Appendices would be included in the standalone ILP, and provide a comprehensive

summary of the specific issue being addressed. It is assumed that all parties using this document do not have the

same level of understanding about what might be complex terms, and therefore reduces inefficiencies created from

misunderstanding.

14

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

APPENDIX 2: YEAR 3 ENGLISH CONTENT DESCRIPTIONS

LANGUAGE

Language variation and

change

Understand that languages have different written and visual

communication systems, different oral traditions and different ways of

constructing meaning (ACELA1475)

Language for interaction

Understand that successful cooperation with others depends on shared use

of social conventions, including turn-taking patterns, and forms of address

that vary according to the degree of formality in social situations

(ACELA1476)

Examine how evaluative language can be varied to be more or less forceful

(ACELA1477)

Text structure and

organisation

Understand how different types of texts vary in use of language choices,

depending on their purpose and context (for example, tense and types of

sentences) (ACELA1478)

Understand that paragraphs are a key organisational feature of written

texts (ACELA1479)

Know that word contractions are a feature of informal language and that

apostrophes of contraction are used to signal missing letters (ACELA1480)

Identify the features of online texts that enhance navigation (ACELA1790)

Expressing and

developing ideas

Understand that a clause is a unit of grammar usually containing a subject

and a verb and that these need to be in agreement (ACELA1481)

Understand that verbs represent different processes, for example doing,

thinking, saying, and relating and that these processes are anchored in

time through tense (ACELA1482)

Identify the effect on audiences of techniques, for example shot size,

vertical camera angle and layout in picture books, advertisements and film

segments (ACELA1483)

Learn extended and technical vocabulary and ways of expressing opinion

including modal verbs and adverbs (ACELA1484)

Understand how to use soundletter relationships and knowledge of

spelling rules, compound words, prefixes, suffixes, morphemes and less

common letter combinations, for example tion (ACELA1485)

Recognise high-frequency sight words (ACELA1486)

LITERATURE

Literature and context

Discuss texts in which characters, events and settings are portrayed in

different ways, and speculate on the authors reasons (ACELT1594)

Responding to literature

Draw connections between personal experiences and the worlds of texts,

and share responses with others (ACELT1596)

Develop criteria for establishing personal preferences for literature

(ACELT1598)

Examining literature

Discuss how language is used to describe the settings in texts, and explore

how the settings shape the events and influence the mood of the narrative

(ACELT1599)

Discuss the nature and effects of some language devices used to enhance

15

Debra da Silva

SID #18252191

meaning and shape the readers reaction, including rhythm and

onomatopoeia in poetry and prose (ACELT1600)

Creating literature

Create imaginative texts based on characters, settings and events from

students own and other cultures using visual features, for example

perspective, distance and angle (ACELT1601)

Create texts that adapt language features and patterns encountered in

literary texts, for example characterisation, rhyme, rhythm, mood, music,

sound effects and dialogue (ACELT1791)

LITERACY

Texts in context

Identify the point of view in a text and suggest alternative points of

view(ACELY1675)

Interacting with others

Listen to and contribute to conversations and discussions to share

information and ideas and negotiate in collaborative situations

(ACELY1676)

Use interaction skills, including active listening behaviours and

communicate in a clear, coherent manner using a variety of everyday and

learned vocabulary and appropriate tone, pace, pitch and

volume(ACELY1792)

Plan and deliver short presentations, providing some key details in logical

sequence (ACELY1677)

Interpreting, analysing,

evaluating

Identify the audience and purpose of imaginative, informative and

persuasive texts (ACELY1678)

Read an increasing range of different types of texts by combining

contextual, semantic, grammatical and phonic knowledge, using text

processing strategies, for example monitoring, predicting, confirming,

rereading, reading on and self-correcting (ACELY1679)

Use comprehension strategies to build literal and inferred meaning and

begin to evaluate texts by drawing on a growing knowledge of context,

text structures and language features (ACELY1680)

Creating texts

Plan, draft and publish imaginative, informative and persuasive texts

demonstrating increasing control over text structures and language

features and selecting print, and multimodal elements appropriate to the

audience and purpose (ACELY1682)

Reread and edit texts for meaning, appropriate structure, grammatical

choices and punctuation (ACELY1683)

Write using joined letters that are clearly formed and consistent in size

(ACELY1684)

Use software including word processing programs with growing speed and

efficiency to construct and edit texts featuring visual, print and audio

elements (ACELY1685)

Source: www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/english/curriculum/f-10?layout=1#level3

16

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Teaching Vol. 2: Stories Reflecting the ClassroomD'EverandTeaching Vol. 2: Stories Reflecting the ClassroomPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gold Coast Transformed: From Wilderness to Urban EcosystemD'EverandThe Gold Coast Transformed: From Wilderness to Urban EcosystemTor HundloePas encore d'évaluation

- Individual Learning Plan (Ilp)Document17 pagesIndividual Learning Plan (Ilp)api-358808082Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment1 ECL310 NaomiMathew 212198847Document20 pagesAssignment1 ECL310 NaomiMathew 212198847Naomi MathewPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 3 IlpDocument13 pagesAssignment 3 Ilpapi-405568409Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan Writing Camperdown College 1Document4 pagesLesson Plan Writing Camperdown College 1api-454406266Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edn2104 - Tasks 1-11 Carly Williamson 32468197Document13 pagesEdn2104 - Tasks 1-11 Carly Williamson 32468197api-330742087Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edfd Final IlpDocument16 pagesEdfd Final Ilpapi-318069438Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 2 - Project - Tyla MilichDocument21 pagesAssignment 2 - Project - Tyla Milichapi-469895619Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment Task 3Document16 pagesAssessment Task 3api-319867689Pas encore d'évaluation

- s1 - Edla Unit JustificationDocument8 pagess1 - Edla Unit Justificationapi-319280742Pas encore d'évaluation

- English 3 Assignment 2 FPD TemplateDocument21 pagesEnglish 3 Assignment 2 FPD Templateapi-350667498Pas encore d'évaluation

- Running Header: STUDENT CASE STUDYDocument5 pagesRunning Header: STUDENT CASE STUDYapi-354980593Pas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Based Plan - Alanah Knight Emma RuwoldtDocument23 pagesLiterature Based Plan - Alanah Knight Emma Ruwoldtapi-419560766Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edma342 Assessment Task 2 s00289446Document3 pagesEdma342 Assessment Task 2 s00289446api-668554441Pas encore d'évaluation

- Emt691 At2 - Jake OconnorDocument7 pagesEmt691 At2 - Jake OconnorJake OConnorPas encore d'évaluation

- 4.RL - RRTC .10 Read and 4.RI - IKI.8 Explain How An 4.RI - IKI.8 Explain How An Author Uses 4.FL - WC.4 Know and Apply GradeDocument15 pages4.RL - RRTC .10 Read and 4.RI - IKI.8 Explain How An 4.RI - IKI.8 Explain How An Author Uses 4.FL - WC.4 Know and Apply Gradeapi-383778148Pas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of The Lesson and The Texts FeedbackDocument12 pagesAnalysis of The Lesson and The Texts Feedbackapi-450524672Pas encore d'évaluation

- Diff Assignment 2Document11 pagesDiff Assignment 2api-478112286Pas encore d'évaluation

- E Portfolio Evidence Standard 3 4 and 5Document13 pagesE Portfolio Evidence Standard 3 4 and 5api-287660266Pas encore d'évaluation

- Log-Reflection - Nikki Byron FinalDocument38 pagesLog-Reflection - Nikki Byron Finalapi-414376990Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final Lesson Plan 1Document8 pagesFinal Lesson Plan 1api-398280606Pas encore d'évaluation

- Forward Planning Document Primary 1Document7 pagesForward Planning Document Primary 1api-354080648Pas encore d'évaluation

- Literacy Unit of WorkDocument24 pagesLiteracy Unit of Workapi-358610317100% (1)

- Edet300 At2Document3 pagesEdet300 At2api-668554441Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment 2 Lesson PlanDocument16 pagesAssessment 2 Lesson Planapi-462010850Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 3 - IlpDocument12 pagesAssignment 3 - Ilpapi-352958630100% (1)

- Primary Final Report - 2019-1 Ellie 1Document6 pagesPrimary Final Report - 2019-1 Ellie 1api-478483134Pas encore d'évaluation

- Case Study Assignment 2Document10 pagesCase Study Assignment 2api-408336810Pas encore d'évaluation

- Behavior Mod ProjectDocument7 pagesBehavior Mod ProjectBridget PattersonPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 2 Case StudyDocument6 pagesAssignment 2 Case Studyapi-427319867Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reflection of Assessment Strategies 2017Document5 pagesReflection of Assessment Strategies 2017api-263506781Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment Two EdfdDocument8 pagesAssessment Two Edfdapi-265573453Pas encore d'évaluation

- What A Writer Needs Book ReviewDocument9 pagesWhat A Writer Needs Book Reviewapi-316834958Pas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence - 2Document5 pagesEvidence - 2api-358837015Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edac Assessment 3Document11 pagesEdac Assessment 3api-317496733Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hass Unit PlannerDocument3 pagesHass Unit Plannerapi-464562811Pas encore d'évaluation

- Esm310 Scott Tunnicliffe 212199398 Assesment 1Document8 pagesEsm310 Scott Tunnicliffe 212199398 Assesment 1api-294552216Pas encore d'évaluation

- Esm310 Assignment Cummings Jolly Martin WilsonDocument12 pagesEsm310 Assignment Cummings Jolly Martin Wilsonapi-294362869Pas encore d'évaluation

- English FPDDocument19 pagesEnglish FPDapi-357680810Pas encore d'évaluation

- GoalsDocument2 pagesGoalsapi-368446794Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ideology ReflectionDocument3 pagesIdeology Reflectionapi-283385206Pas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum 1a-Assessment 1Document4 pagesCurriculum 1a-Assessment 1api-522285700Pas encore d'évaluation

- Inclusion, Policies + LegislationDocument13 pagesInclusion, Policies + Legislationapi-526165635Pas encore d'évaluation

- Activity Plan 0 To 3 YearsDocument3 pagesActivity Plan 0 To 3 Yearsapi-357680810Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edla450 Assessment 2 LessonsDocument18 pagesEdla450 Assessment 2 Lessonsapi-239396931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edfd340 Assignment 2Document9 pagesEdfd340 Assignment 2Nhi HoPas encore d'évaluation

- Edla439 Assessment Learning PlanDocument13 pagesEdla439 Assessment Learning Planapi-461610001Pas encore d'évaluation

- WeeblyDocument2 pagesWeeblyapi-517802730Pas encore d'évaluation

- EDU412 Task 3: Case Study Jason - ADHDDocument8 pagesEDU412 Task 3: Case Study Jason - ADHDapi-366249837Pas encore d'évaluation

- Catholic Studies Unit Planner - Religious Authority For EthicsDocument29 pagesCatholic Studies Unit Planner - Religious Authority For Ethicsapi-470676217Pas encore d'évaluation

- Literacy Continuum ESL Scales and EALD October 2013Document18 pagesLiteracy Continuum ESL Scales and EALD October 2013S TANCRED75% (4)

- Inclusive Assignment 2Document12 pagesInclusive Assignment 2api-435738355Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment 1 Lesson Plan and CritiqueDocument12 pagesAssignment 1 Lesson Plan and Critiqueapi-327519956Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hass Lesson SequenceDocument6 pagesHass Lesson Sequenceapi-332081681Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson SequenceDocument16 pagesLesson Sequenceapi-461551715Pas encore d'évaluation

- Primary Science FPD 5esDocument19 pagesPrimary Science FPD 5esapi-444358964Pas encore d'évaluation

- Han Xu 183159 Emt603 At2 Essay 1Document10 pagesHan Xu 183159 Emt603 At2 Essay 1api-297844928Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ubd Lesson Plan - AssessmentDocument2 pagesUbd Lesson Plan - Assessmentapi-242935457Pas encore d'évaluation

- Unit Title: Law & Citizens Citizenship, Diversity & Identity Year Level: Grade 7Document4 pagesUnit Title: Law & Citizens Citizenship, Diversity & Identity Year Level: Grade 7api-298200210Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ie Magazine 3 2015 LRDocument36 pagesIe Magazine 3 2015 LRapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Code of Conduct VitDocument6 pagesCode of Conduct Vitapi-319658890Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edu5teb Assignment BDocument8 pagesEdu5teb Assignment Bapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Codeofethicsposter 20081215Document1 pageCodeofethicsposter 20081215api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edu5tea Part B ReflectionDocument7 pagesEdu5tea Part B Reflectionapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edu5csd Assignment 1bDocument8 pagesEdu5csd Assignment 1bapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edu5csd Assignment 1aDocument6 pagesEdu5csd Assignment 1aapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edu5tec Ict ToolDocument7 pagesEdu5tec Ict Toolapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- LDP Assessment 2Document37 pagesLDP Assessment 2api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thursday Lesson PlansDocument8 pagesThursday Lesson Plansapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Busmgt1 Lesson Plan 3Document2 pagesBusmgt1 Lesson Plan 3api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Busmgt1 Lesson Plan 1Document2 pagesBusmgt1 Lesson Plan 1api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Busmgt1 Lesson Plan 3Document2 pagesBusmgt1 Lesson Plan 3api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- His3 Lesson Plan 10Document4 pagesHis3 Lesson Plan 10api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- His3 Lesson Plan 7Document7 pagesHis3 Lesson Plan 7api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- PPW Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesPPW Lesson Planapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- His3 Lesson Plan 5Document8 pagesHis3 Lesson Plan 5api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Morning Session Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesMorning Session Lesson Planapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- His3 Lesson Plan 6Document3 pagesHis3 Lesson Plan 6api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- His3 Lesson Plan 2Document4 pagesHis3 Lesson Plan 2api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- His3 Lesson Plan 4Document11 pagesHis3 Lesson Plan 4api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Maths Year 1 Unit 6 Lesson 19Document2 pagesMaths Year 1 Unit 6 Lesson 19api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- p-2 Geography Lesson 3Document4 pagesp-2 Geography Lesson 3api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edu5tec Numeracy LessonDocument10 pagesEdu5tec Numeracy Lessonapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edu5tec Running Record RevisedDocument4 pagesEdu5tec Running Record Revisedapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thursday 22 October: Key Teaching FocusDocument5 pagesThursday 22 October: Key Teaching Focusapi-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- His3 Lesson Plan 10Document4 pagesHis3 Lesson Plan 10api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Maths Lesson Plan 3 LongitudeDocument3 pagesMaths Lesson Plan 3 Longitudeapi-279746002100% (1)

- Maths Lesson Plan 1Document4 pagesMaths Lesson Plan 1api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- His3 Lesson Plan 9Document4 pagesHis3 Lesson Plan 9api-279746002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Abdul Moeed: Duration: - August 2018 To April 2019 Work DoneDocument2 pagesAbdul Moeed: Duration: - August 2018 To April 2019 Work DoneMOHAMMAD SALMANPas encore d'évaluation

- Maslow's Hierarchy of NeedsDocument7 pagesMaslow's Hierarchy of NeedsMaan MaanPas encore d'évaluation

- Prueba de Acceso Y Admisión A La Universidad: Andalucía, Ceuta, Melilla Y Centros en MarruecosDocument3 pagesPrueba de Acceso Y Admisión A La Universidad: Andalucía, Ceuta, Melilla Y Centros en MarruecosNatalia FleitesPas encore d'évaluation

- Concept Attainment Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesConcept Attainment Lesson PlanPrachi JagirdarPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 6 Types of Speeches 2Document20 pagesModule 6 Types of Speeches 2Its KenchaPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Local NetworksDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Local NetworksLouie ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Arminda Nira Hernández Castellano OLLDocument19 pagesArminda Nira Hernández Castellano OLLArminda NiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Athey 2015Document2 pagesAthey 2015MunirPas encore d'évaluation

- Arts AppreciationDocument24 pagesArts AppreciationClarissaB.OrpillaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Strange Case of Agoraphobia A Case StudyDocument4 pagesA Strange Case of Agoraphobia A Case StudyChhanak Agarwal100% (1)

- 2023 RPT English Year 2Document19 pages2023 RPT English Year 2Gitanjli GunasegaranPas encore d'évaluation

- English Learning Kit Deliver A Self-Composed Speech: Junior High SchoolDocument8 pagesEnglish Learning Kit Deliver A Self-Composed Speech: Junior High SchoolEmily Jane TaleonPas encore d'évaluation

- Spanish MaterialsDocument3 pagesSpanish MaterialsCarlos RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Ing GrisDocument13 pagesIng GrisF & I creationPas encore d'évaluation

- One-Pagers: Trying To Deliberately Increase The Chances of LearningDocument15 pagesOne-Pagers: Trying To Deliberately Increase The Chances of Learningyong enPas encore d'évaluation

- BRM Assignment-4Document23 pagesBRM Assignment-4Sarika ArotePas encore d'évaluation

- The Looking Glass Self BotanywaybootDocument1 pageThe Looking Glass Self BotanywaybootRanie MonteclaroPas encore d'évaluation

- Job Analysis QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesJob Analysis QuestionnairebarakatkomPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 6Document16 pagesModule 6mahreen habibPas encore d'évaluation

- Discourse Analysis ModuleDocument45 pagesDiscourse Analysis ModulejesuscolinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Cardboard SceneDocument2 pagesCardboard Sceneapi-630719553Pas encore d'évaluation

- Curriculum Map Science 7Document6 pagesCurriculum Map Science 7Lucelle Palaris100% (8)

- Providing Educational Feedback: Higher Education ServicesDocument8 pagesProviding Educational Feedback: Higher Education Servicesدكتور محمد عسكرPas encore d'évaluation

- Cues For Weightlifting CoachesDocument4 pagesCues For Weightlifting CoachesDiegoRodríguezGarcíaPas encore d'évaluation

- 33 Soalan Bocor Utk VIVADocument2 pages33 Soalan Bocor Utk VIVAZainorin AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning: December 2020Document5 pagesDisease Prediction Using Machine Learning: December 2020Ya'u NuhuPas encore d'évaluation

- HRM Syllabus-2012-Hoang Anh DuyDocument4 pagesHRM Syllabus-2012-Hoang Anh DuyNghĩa SuzơnPas encore d'évaluation

- Https://id Scribd com/presentation/318697430/Healthy-CityDocument14 pagesHttps://id Scribd com/presentation/318697430/Healthy-CityIna Fildzah Hanifah100% (1)

- Consumer Profile Project - WhirlpoolDocument12 pagesConsumer Profile Project - WhirlpoolAnonymous 5GHZXlPas encore d'évaluation

- Educ. 201 Bsed 2bDocument6 pagesEduc. 201 Bsed 2bDaryl EspinoPas encore d'évaluation