Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Mintzberg H, The Managers Job, Folklore and Fact

Transféré par

Amos Yap0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

312 vues13 pagesarticle

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentarticle

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

312 vues13 pagesMintzberg H, The Managers Job, Folklore and Fact

Transféré par

Amos Yaparticle

Droits d'auteur :

© All Rights Reserved

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 13

w

The manager's job:

folklore and fact

Henry Mintzberg

The classical view says that

the manager organizes,

coordinates, plans, and controls;

the facts suggest otherwise

uae what des the maser

dottor yen the menage,

the hear of he orgies

tion, has ben assumed 12

te lite an orchena

lear, contaling the

ios pare of Bi

rganizstion wih the ease

nd rein of Se

rawe: However when

oe lake at he ew

‘len that ave been

‘onecoveng mancgera

postions fo the

Prnident of te Uaited

Siew ect ang

leader acs show

(at manager ae not

etecive replated

wie infomed by

Sele manive

st inerpenoet, nor

‘Sato sad deena!

‘rant be mere eee.

shat hel Jo ell i

Ind then oe the resources

Schand wo supper rather

than hamper their own

sare. Undentanding

Sesing themselves takes

toes intespen tad

bjectiviy onthe mane

ges par At te nd

Fhe trie the sther

Includes a see of erty

‘qustoas vo elp provide

Secs

Me, Miners ia asociate

‘profesor inthe acl of

‘Management at Mecil

Univer, Montes

(Canada He i curreatly

2 ring profesor at

enue dead ot

Recherche sr fer

‘ongninona et It geaon

AE} im Aicene

Provence, rane. Some of

the mate ia hi srele

in‘condened fron he

fSuthors book The Nase

Of danagel Work,

publihed by Hamer &

If you ask a manager what he does, he will most

Likely ell you that be plans, organizes, coordinates,

and conuols. Then watch what he does, Don't be

Surprised if you can't relate what you see to these

four words.

‘When he is called and told that one of his factories

has just bummed dowa, and he advise che caller

see whether temporary arengements can be made

to supply customers through «foreign subsidiary, is

Ihe planning, organizing, coordinating, or contol

ling! How about when be presents «gold watch t

4 redring employee! Or when he attends « confer

nce to meet people inthe tide! Or on returning

from that conference, when he tells one of his em-

ployees about an interesting product idea he picked

Up there?

‘The fat is that these four words, which have dos

inated management vocabulary since the French in:

userlist Henri Fayol Ars ineoduced them in 1926,

tell us litle about what managers actually do, AC

best, they indiete some vague objecuives managers

Ihave when they work

‘The Reld of management, 0 devoted to progess and

change, has for more than hell «century no serious

ly adetessed the basic question: What do managers

dol Without « proper snawer, how oan we seach

‘management! How can we design planning or in.

formation systems for managers! How ezn we ia

prove the practice of management at all!

(Our ignorance of the nature of managerial work

shows up in various ways ia che modem organiza.

flonvia the boast by the successful manager that

he never spent a single day in a management waar

{ng piogam, in the curnover of corporate olanners

who never quite understood what ie was the mas

ager wanted) in the compucer consoles gathering

‘duet in the backroom because the managers never

used the fancy omline MIS some analyst thought

they needed, eshaps most important, our ignorance

hove up in the inability of our letge public of

{nizations to come to gripe with some of their most

serious policy problems.

Somehow, inthe rash c0 sutomste production, to

‘use management science in the functional areas of

marketing and finance, and to apply the skills of

the behavioral scientist f0 the problem of worker

‘motivation, the manager-that pezsoa in charge of

the organisation of one of it subunits—has been

forgocten,

My intention in this aricl is simple: to break the

reader away from Fayol's words and inuoduce him

to's more supportable, and whet I believe «9 be 2

‘more useful, description of managedial work. This

descripdon derives from my review and synthesis

of the available research on how various managers

Ihave spent ther time.

In some sedies, managers were cbserved intensively

(shadowed isthe term some of them used); in 2

‘numberof other, they kept detailed diaries of thie

Actives in a few stadies, their ecords were an

alyzed, All kinds of managers were studied=fore

nen, factory supervisor, staff managers, Geld sles

‘manager, hospital administrator, presidents of com.

panies and nations, and even street gang leaders,

‘These “managers” worked in the United States,

Canada, Sweden, and Great Britain. In the ruled

insert on page 53 8 4 brief review ofthe major stud

fe that I found most wefal ia developing this de

seciption, including my own sedy of five American

Chief executive officers

A synthesis of these Gadings paints an interesting

Picture, one as diferent from Fayol's classical view

45 cubist absuae ie from a Renaissance painting

ina sense, this picture will be obvious to anyone

who hat ever speat a day in a manzger's ofce,

‘ithe im front ofthe desk or behind te Ye, at the

Same ime, this picture may turn out t be revolu

Wonscy, in that throws into doube so much ofthe

folklore chat we have secepted about the manager

work.

{Brat discuss some of this folklore and contrast it

with some ofthe discoveries of systematic research

{he hard facts about how managers spend thew me

‘Then T synthesize chese research Bindings in a de.

sestotion of ten goles that seem to describe the es

‘ential content of all manages jobs. Ina concluding

fection, I discuss « number of implications of this

synthesis for those eying to achieve more efecive

‘Blanegement, both in classrooms ead a the business

woul

Some folklore and facts about

managerial work

‘There are four mychs about the managers job that

do not bear up under careful senitiny of the fact

1

Folklore: The manager is a reflective. systematic

planner. The evidence on this issu is overwnelm-

Ing, but noc shred of ie suppors this statement

ace: Seudy afer study has shown that managers

‘work qt an unrelenting poce, chat their ectivites are

characterized by brevity, vatiery, and discontinuity,

dnd that they ate scongiy oriented to action and

dislike reflective acuvities. Consider this evidence

o

Hilf the acelvties engaged In by the five chief ex-

coutives of my seudy lasted less than nine minutes,

snd only of exceeded one hour! A study of 56

US. foremen found that they averaged 583 acivites

per elghehour shift, an average of t every 48 sec:

(nds The work pace for both chief executives and

foremen was unrelenting. The chief exeeutives met

4 steady steam of calles and mail from the moment

they arnved in the moraing atl they left in the

evening, Cole bresks and lunches were Ineviably

‘work related, and ever present subordinates seemed

{9 usurp any free moment.

a

AA diary study of 160 British middle and top man-

agers found che they worked fora half hour or more

‘wiehout incerruption only about once every eo

days

a

(Of dhe verbal contaess ofthe chief executives in my

study, 93% were aranged on an ad hoe basis. Only

1% of the executives time was spent in open-ended

observational tours. Only 1 out of 368 verbal con:

(acts was unvelated ta specific issue and could be

sale general planning “Another scercer fads

that "in aot one single case did a manager report the

obtaining of importante extemal information fom 4

general converscion of other unduetied pesonal

°

No study bas found important pattems in the way

‘managers schedule cher time. They seem to ump

from isue to issue, continually responding t0 the

seeds of the moment.

Is cis the planner that th classical view describes?

Hardly. How, thea, can we explain this behavior!

‘The manager is simply responding to the presses

of his job. I found that my chiet executives ter

‘minated many of their own aetviies, often leaving

‘meetings before the end, and interrupted their desk

‘work teal in subordinates, One president not only

placed bis desk so that he could foo downs long

fallway bue also lef hie dooc open when he sae

alone~an invitation for subordinate 10 come in

sd interupt him.

Cleary, these manasers wanted to encourage the

flow of current information. But more significantly,

they seemed tp be eonditioned by their own work

loads. They appreciated the opporeuniy cost of thee

own time, and they were continually awate of

their ever present obligatons-mail to be answered,

callers to attend to, and so on. It seems that no

matter what he is doing, the manager is plagued by

the possiblities of what he might do and what he

must do.

‘When the manager must plan, he seems to do so

‘enplictly in the context of daily setons, not in

some abstract process reserved for two weeks ia

the organization's mountain rettsat The plas of

the chief executives {studied seemed to exist only

in thes Readswas evble, but often specif, inten

tions. The traditional lierseure notwithstanding. the

job of managing does not breed restive planters,

the manager is 2 tealtime responder to stills a

Individual who is conditioned by his job to prlet

live to delayed action.

Folkiore: The efecaive manager has no regular dx

‘ues to perform. Managers ate constantly being ‘old

to spend more time planning and delegating, ond

less time seeing customers and engaging ia negota-

soon Then are not ter ll the aves of she

manager. To use the popular analogy, the good

‘manager, ike the good tonductor,eatfully orehes:

leates everthing in advance, then sis back to enjoy

the fruits of his labor, responding occasionally oe

‘unforeseeable exception,

‘But here again the pleasant abstscton just does aot

seem to hold up. We had better take a closer look

st those activites managers feel compelled to tm:

‘age in before we arbiwany define them sway,

Fact: n addition 10 handling exceptions, managerial

work involves perfonning a number of regulat di

Wes, including ritual and ceremony, negotiations,

and processing of soft information that links the

organization with ts envuament. Consider some

evidence from the research studies:

°

A seudy of the work of the presidents of small com

Panies found chat they engaged in toutine aciiies

‘because their companies could not afford seat spe.

clalsts and were so thin on operating personnel that

4 single absence often required the president to sub

a

One study of field sales managers and another of

chief executives suggest that ite a natural pet of

both jobs to see important customers, asumlag the

anager wish to hep shove custome

‘Someone, only half in jest, once described the man

gee as that person who sees vistors wo that everyone

else can get his work done. In my study, 1 found

‘hat certain ceremonial daues—mecting visting dig:

itaies, giving out gold watches, presiding a Chiat.

amas dinaers~were an intrinsic par ofthe eble! ex

ecutive ob.

Studies of manager’ information Gow suggest that

‘managers play a key role in securing "soft" external

information {much of (e avalsble only thems

because of their status) and i passing ic aloag to

thee subordinates

3

Folklore: The senior manager neede aggregated ins

formation, which a formal management efermation

jyutem beie provides. Not too long ago. the wands

total information system were everywhere ia the

‘management literature. tn keeping with the clanical

view of the manager as that individual perched on

the apex of a regulated, hierarchical system, the

lieracure's manager was to receive all his important

‘information fom a gant, comprehensive MIS,

But lately, as it has become increasingly evident

thar these gane MS systems are aot working that

managers ate simply not using theme ent

sHaum has waned, A look st how mansgers actually

process information makes the reson quite clear

‘Managers have five media a their commend docu:

ments, telephone calls, scheduled and unscheduled

meetings, and observational tour,

Fact: Managers strongly favor the verbal media~

namely, als and meetings. The evidence

comes from every single study of managerial work.

Consider the following:

o

1a ovo Bridsh studies, managers spent an average

(Of 66% and fo% of cheir time in verbal [oral] com

‘munication’ In my study of ve American chief

gece the gue wa 78%.

‘These Sire chief executives wreated mail prcesing

454 burden tobe dispensed with. One came in Sat

lurday morning to process 43 pieces of mail in just

lover three hour, to “get rid of al che stuf." This

sume manager looked at the fist piece of “bard”

‘all be had received all week, a standard cost te

port and pue it aside with che comment, "never

Took se cis”

a

These same five chief executives responded immedi-

ately t0 2 of the 4o routine reports they received

uring the five weeks of my study and 9 four items

in the 10s periodicals. They skimmed most of these

peviodicals in seconds, almost situalistially. In al,

these chief executives of good-sized organizations

fnidated on their own~that is, not in response (©

something clsewa grand toual of 35 pieces of mail

during the 25 days T observed thea

‘An analysis of the mail the executives received 1

vealsan interesting pieture-only 23% was of specie

tnd immediate ure, So now we have another piece

in the purse: not much of the mall provides live

current informauon-the acxon of a competitor, he

‘ood of a govemment epilator, or the rating of

Digit television show Yer this the infoner

sion that drove the managers, interupeing theit

meetings and rescheduling thie workdays,

(Consider another interesting Binding, Managers seem

to cherish "sole" information, eepecally gossip,

Ihearsay, and speculation. Why! The seston isis

timelines; today's gosip may be tomorrow's fact.

‘The manager who is not accesible for the telephone

call informing him chat his biggest customer was

Seen goldag with bis main compeutor may read

about a dramade drop in sles in the next quartely

report. Bue chen t's too late

‘To assess the value of historical, aggregated, “hard”

IMIS information, consider two of the managers

Drime uss for bis information=to identity problems

{and opportunices ® and to bullé his own mental

models of che things around him (eg, bow his ot-

ganizaton’s budget ayetem works, how his cus:

fomers buy his product, how changes in the eq”

omy affect his organisation, and t0 on). Every\.c

of evidence suggests that the manager identifies

decision situations and builds models not with the

egregeted abstractions an MIS provides, but with

specific dies of daa.

Consider the words of Richard Neustadt, who stud

fed the informationollecting habits of Presidents

Roosevelt, Truman, and Evsenhovwer

“Te is not information of + general sore that helps

a President se personal stakes; not summaries, not

Surveys, aot the bland amalgams. Rather... leis the

fdas and ends ofrangible deal that pieced together

im bis mind illuminate the underside of issues pat

before him. To help himself he must reach out 38

widely 26 he ean for every srap of fae, opinio

fps bearing on his inert ad reasoning

President. He must became his own director of C+

own centeal intelligence," *

‘The manager’ emphasis on the verbal media raises

‘eo important points

First, vebal information is stored in the brains of

people. Only when people write this information

own can it be stored in the files of the organ

leation—whether in metal cabinets of on map.

netic tpenand managers apparently do aot write

own much of what they hear, Thus the stateple

aa bank of the organication isnot in the memory

of its computers but in the minds of its manager

Second, dhe wane’ extmsive we of verbal media

helps to explain why he is reluctant to delegate

tasks When we note chat most of the manage

Important information comes in verbal form and is

stored in his head, we can well appreciate fis telue-

tance Ie s not as if he cun hands dower over 10

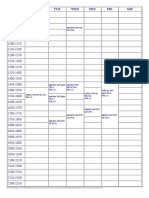

Research on managerial work

Sorc a way

ictal tae

Sa

Sas,

SE

eu ty

ete) Sg

Ease

eo rcue aune

Sey

8

tonal Sonor toe

Severe” aye

Irene compury,

Foe H, Gus in Parson

pe rpara oe ay oo

‘SPS froma vert aoe

‘ne oghenoer nt

epee tod nan

US nab Pam tay

Sremtosn

sa et

ieee

ee

ec

fSrmaso sve Nim be

someone, he must take the time to “dump memory”

“to ell that someone al he knows about the su

ject But this could take 20 long that the manager

may find it carer to do the tank himeelt Thus the

‘manage is daroned by his own information sysexs

to "dilemma of delegation”-t0 do too much him

{elf o 10 delegate his subordinates with ined

equate briefing

Tolklor Management i, of wt last Us quickly be

‘coming, a science and a profesion. By almost ny

definitions of science and profesion, this statement

ts alse. Brief observation of any manager will quick

Jy ly wo est the notion that managers practice 3

science. A science involves the enacton of syste

tats, spalytcally determined procedures or

trams. If we do not even know what rocedees

{managers tse, bow can we presen them by cleat

{ihe analysis And how ean we eal manafesent

2 proesion if we cannoe specify whae managers

tre 9 lesm? For ser ll, « profession mvelves,

emowiedge of sue depacsaen of luming 2

cence” [Random Howse Dictionary|

Fact: The managers’ programs—to schedule tim

prowess information, sake decisions, ond 20 0

femain locked deep inside thelt Dring. Ths, 10

describe these programs, we rely on words like dg.

‘ment and incuton, seldom stopping to realize that

they are merely labels for our ignorance.

1 was struck during oxy seedy by the face chat the

cxceutives [ was observingwall very competent by

Sy standatd~are fundamentally indisdingushable

(fom their counterpers of 4 hundred years ago

for 4 thousand years ago, for that mater). The

Iefotmation they need dilers, Dur they seek it ia

the tame way—by word of mouth, Their decisions

‘oncem modem tecanoiogy, but the procedures they

{se to mule them ate te sume st the procedures

or che nineteenth century manage. Even the com-

‘uter, 2 important for the spectalzed work of the

Srganisation, has apperently had no ladluence on

the work procedures of general managers, In fact,

the manager isin + kindof loop, with increasingly

heavy work prerures but 20 id forthcoming from

management science.

Considering the facts shout managerial work, we

Gn se thatthe managers jb is enormously com:

flcsed and dsicale The managers overburdened

Irth obligations, yet be cannot eanly legate hs

{ia As erly be is driven 0 overwos and

ferent to do many tasks supertally. Breve, fag

teens, and wrbal communication charset

Es work Yer thee aze the very chaactensts of

Imenageial work that have impeded sled

wrt inp fe Ana result the management

‘Sess har concentrted hs elf onthe special

Eat funeions ofthe organization, were he could

tao easily sualyae che procedurer and quanuly

the mdevane nformanon™

But the pressures ofthe manager’ jb ace becoming

‘worse, Where before he needed only to respond %0

‘Swner and director, now he nds that subordinates

‘wich democratic norms continwally reduce bis Fre

dom to issue unexplained orders, anda growing

number of outside influences [consumer soups,

{government agencies, and so os) expect his atten

Hon. And the manages has bad nowhere to cumn for

hnlp. The dist step is providing the manager with

some help ist Sind out what hijab really

Back to a basic description

of managerial work

pussle togecher Eater, I defined the mansger a6

that person in charge ofan organization or one of

les subunits. Besides chief execuaive officers, this

definition would include vice presidens, bishops,

foremen, hockey couches, nd prime ministers. Can

ail ofthese people have anyehing én common! In

eed they can. For an Important raring point, all

fare vesed with fonal authosity over en organiza

tonal unit From formal suthorty comes stats,

Wich leads fo various interpersonal relations, and

from these comes access to information. Informs:

‘on in turn, enables the manager w@ maxe dessions

sd suategies for hs unie

‘The manager's job can be described in tems of

‘various "oles," or organized sets of behaviors iden-

{led with position. My desceiption, shown in

Evhibie/, comprises ten tole As we shal se, formal

awhoriey gives rise fo the thre interpersonal roles,

‘which in furm give rise to the chee informations)

roles, these two sets of roles enable the manage

to play the four deesional roles.

Interpersonal roles

‘Thee of the managers roles arse dzeetly from bis

formal authoriey and involve basic interperonal

relationships

1

Frei che figurehead role. By virtue of his postion

4s head of an organizational unit, every manager

‘must perorm some duties of 4 ceremonial nature

‘The president grees the touring dignitaries, the fore

man attends the wedding of a lathe operator, and

the sales manager takes am important customer (0

lunch

‘The chief executives of my soudy spent safe of

heir contact time on ceremonial dates, 17% of

their incoming tail dealt with acknowledgments

nd requers related to their statue. For example, &

fewer to 2 company president equested free met-

chandise fora erppled schoolehld, diplomas were

put on the desk of ehe school superintendent for

Bis signature,

Duties that involve interpersonal roles may some

times be outine, involving litle serious communica:

fon and no important decision making, Neverthe:

less, they are important fo che smooth functioning

of in organization and cannot be ignored by the

manager

2

Because he is im charge of an organizational uni

the manazers responsible for the work ofthe people

fof that unit. His actions in ehis regard consticue the

leader role. Some of these actlons involve leader

Ship direciy—for example, in most organizations

the manage is normally responsible for biring and

tesning his own stat

In addition, there is the indirect exercise of the

leader sole Every manager must mouvate and en

courage his employees, somehow reconciling their

Individual needs with the gols of the organization

In vireally every coneact the manager hae wih his

cmployees, subordinates seeking leadership clues

probe is actions: "Does he approve!” "How would

be like the report to turn out?” "Ts he more inter

ccted in macket share than high profs!”

‘The influence of the manager is most cleanly scea

inthe lesder tole. Formal authority vests him with

treat potential power, leadership determines in urge

pate How much of i he will realize.

3

‘The lneraure of managemenc has always recognized

the leader role, paruiculady hose aspect of ire

Iated ta marivinion. In comparison, tail recently

teas harly mentioned the lion role, ia which

the manager maker contacts outside his vertical

chain of command. This Is semarkable in light of

the finding of virally every stady of managerial

work that managers spend as much time with peers

{nd other people outside thelr unite ae they do with

‘heir own Subosdinates—and, surprisingly, very lie

time with their own superiors.

In Rosemary Stewards dary arudy, the 160 Brith

‘middle and top manager spent «fe of thee ane

‘with peers, 41% of their me with people outside

their nity and only 13% of thelr deme with thie

superiors. For Robert H. Guests seedy of US, fore

‘en, the figures were 44%, 46%, and 10%. The

Chief executives of my study averaged 44% of their

contact ume with people ouside theit organics

ons, «8% with subotdinates, and 7% with directors

sd trustee,

‘The contscts the ive CEOs made were with an in-

credibly wide range of people: subordinates, clients,

business astocates, and supplier, and peer-man-

ger of similar organizations, government and wade

organization officals fellow directors on outside

boards, and independents with no relevant organiza

‘onal allistions. The chief executive time with

and mal from these groups is shown in Exhbie IT

(on page 57. Guest's study of foremen shows, ike

Wise, that sheir contacts were aumerous and wide

‘anging seldom involving fewer than 35 individuals,

and offen more chan 50,

‘As we shall see shortly, the manager cultivates such

Contacts largely to find information. In eflect, the

liaison fole is devoted to building up che managers

‘own exteral information system~informal, private,

verbal, but, neverteles, effective

Informational soles

By view of his interpersonal contsets, both wich

1s subordinate and with ie network of contacts,

the manager emerges as the nerve center of his or

fanizauonal unit He may aot know everything

Sut he eypically Knows more than any member of

is tag

Studies have shown this relationship to old for at

managers, om street gang leaders 0 US, pres:

dencs. In’ The Humen Group, George C. Homans

‘explains how, because they weve 20 the center of

the information flow in their own gangs and were

slro in clove touch with other gang leedar, eteet

{ang leaders were better informed than any of thes

followers. And Richard Neustadt deseibe the fo.

lowing account ‘om his study of Franklin D.

Roosevelt:

‘rte estnce of Roosevel?'s technique for informs

tion gathering was competition. ‘He would call you

{none of his ides once told me, end he'd ask you

to get the sory on soaie complicated business, and

‘you'd come bac after a couple of days of hard labor

Thu present the juicy morsel you's uncovered under

{one somewhere, and then You'd find out he knew

{labour i slong with something else you didn't

Know. Where he got chis information from he

‘wouldn’ mension, usually, but after be had done

this to you once of ewice you got damn careful

shout your information’

‘We can see where Roosevele “got this information”

when. we consider the relationship beeween the

interpersonal and informational roles. As lesde, the

manager has formal and easy acces t every mem

ber of his staff. Henes, as noted easier, he tends

to know more aboue his own unit than anyone else

does Im addition, hs liaison contacts expose the

‘manager to extemal information to which his sub-

trdinates offen lack access Many of these contacts

fre with other managers of equal stars, who ae

themselves nerve centers in ther owa organization,

In this way, the manager develops powerful data

base of infomation.

“The processing of information is a key part of the

smunager’ job. In my study, the chief executives

spent go% oftheir contact time on acivites devoted

exclusively tothe taasmission of information, 70%

(of their incoming mall was purely Informational

les opposed to requests for action). The manager

doesnot leave mesuags oF hang up the telephone

fn order 9 gee back to work. [a large part, come

trunicaton i his work Three cole deteribe these

Informational aspects of managerial work,

t

‘As monitor, che manager perpetually seans his en

‘vironment for information, interrogrtes his Lisson

contcts and his subordinates, and receives unso

Tieited information, much of itas ¢ result of the

reework of peronal contacts he has developed. Re

member that a food part of the ioformation the

ftanager collects in hie monitor role aries in ver

bal form, often as gossip, hearsay, and speculation.

By wire of hi conten, the manager has a natural

sddvantage in collecting this soft information for his

organizsuon.

2

Fe must share and disebute muck ofthis informs

tion. Information he gleans from outside personal

contacts may be needed within hie organization

In bis issemnator role, the manages passes some

of his pavileged information deeeuyt9 his subor

dinates, who would otherwise have no access to i

‘When his subordinates lack easy contact with one

another, the manager wil sometnes pas informs

fon from one to another

3

Ta his spokesman role, the manager tends some of

his information to people ouside hs unit~s pres

dent makes a speech to lobby for an organization

cause, of a foreman suggests a product modifica

ton tos supplier In adie, a# pare of his role

4s spokesman, every manager must inform and sat-

{sty the influential people who contol his organip~

tional unit. For the foreman, chis may simply inv

keeping the plant manager informed about the ow

of work through the shop.

“The president ofa large corporation, however, may

spend a great amount of his time dealing with 2

hos of iniluences, Dzeciors and shareholders must

be advised about Snancial pesformanee, consumer

‘fous mare be semred thatthe organization i fl:

Sing its social responsibiives, and government

fiias must be saueded hat the organization is

abiding by the law.

Decisional roles

Information is not, of course, an end in isfy i

the basic input to decision making, One thing ‘=

clear in the seudy of managerial work: che mana

plays the major vole in his units decision-making

System. As ie formal auchoriy, only he ean commit

the unit to imporant new courses of action, and

sis nerve center, only he has fall and curren i

formation to make the set of decisions that deter

mines the units srateyy. Four roles describe the

manager as decisionsmaker

1

‘As entrepreneur, the manager seeks to improve his

‘une, to adape it to changing condicons in the en-

vironment. In his monitor role, the president is

constndly of he Ipokout for new idess.'When 4

goed one appear, he initiates a development project

that he may supervise himself or delegate to an em

ployee (permaps wath the suipulaion that he must

Epprove the Sina! propel

‘There are two interesting features about these de-

velopment project at the chief executive level

ss, these process do aot involve single dessions

fr even unified clustrs of decisions, Rather, they

Gmerge a series or small decisions and actions

‘equenced over me. Apparently, the chief executive

prolongs cach project so that he can fi ie bit by bit

Tht his busy, dsjoined schedule and so that he can

ridually come to comprehend the issue, if i i 2

Complex one.

Second, the chief executives I studied supervised ss

‘any a8 9 ofthese project at the same time. Some

projects entailed new products or processes, others

nvolved public celavons campaigns, improvement

of the cash position, earganizaton of 2 weak de

partment, rrolution > 4 morale problem in a for

ign division, integration of computer operations,

arious seauisivons ve diferent stages of develop

sent, and 30 00,

‘The chief executive appears to maintain a kind of

Inventory of the development projets that he him

sell supervisesprojects that are at various stapes of

Sevelopmiene, ome ative and rome in limbo Like

1 jungles, he Keeps + aumber of projects in the ait,

Periodically, one comes down, is given 2 new burst

‘Of energy, dissent back into orbit. At various in

tervals, he put new projects on-stream and discards

old ones.

a

‘Wile the entrepreneur role deserbes the manager

tthe voluntary inator of change, he disturbonce

handler sole depiess the manager involuntanly ze

ponding t9 prewsres. Here change Is beyond the

managers contol. He must act because the pres:

turer of the situation af too severe to be ignored:

Ske looms, a major customer has gone bankrupt,

fr supplier ceneges on his contact.

thas been fashionable, {noted ealer, to compare

the manager to an orchestra coaductor, just a8 Peter

F. Drucker wrote in The Precice of Management:

‘evne manager hat the ean of cresting a ue whole

‘hat larger than che som ofits part, a productive

fenviy that tums out more than the stm of the

{esources put into fe One snalogy isthe conductor

of 2 symphony orchest, through whose efor,

vision and leadership individual insrumental pas

thar ace 20 mech noise by themselves become the

living whole of music. Dut the conductor has the

composers score, he is oaly interpreter, Tae mane

get ie both composer and conductox”"

Now consider the words of Leonard R. Sayles, who

thas caried out systematic research on the mans

ger jb

{The manager i Hke + symphony orchestra con:

ductor, endeavouring to maintain + melodious per

formance in which the contabutions of the various

instruments are coordinsted and sequenced, pat

temed and paced, while the orchestra members are

hing various personal dificulties, stage hands are

‘moving music stands, sltemating excessive heat

tnd cold ate creating audience snd tastrument prob

lems, and che sponor of the concer s insisting on

inraional changes ia che progam’

In effect, every manager must spend a good part of

his time responding to high-pressure disturbances

[No organisation can beso well un, so standardized,

thal hus considered every contingency in the un

fertsia environment in advance. Disturbances srise

fot only because poor managers ignore situations

tint they reach exss proportions, but also because

nad managers cannot poshly anticipate all the

onsequances of the actions they take.

3

“The thied decisional role ie that of esoure allocator

To the manager falls the responsibility of aeccing

Self-study questions for managers

NOSE at Shao

‘rin tne argneaion

‘Pose so peri my

=

Zeeaare, lett

ep. a

Seer

Sm ee

my time munaing ese

Bat tw amy

Sao Sect

ae.

EERIE ow

fon fm socesyhsee, ‘ours my oruauion’

SoS ENS

z Eee

mare

Sone

iar eet toe

Ain oo avout in wnat Tum my deanna my

an ite

tonnage?

oes

Be ccmpetnpe

Eaves

en

sen Se

wo will get what ia bis organizational unit. Per-

fas the moet important resource the manager al-

Tocates i is own time. Acces 19 the manager con:

svutes exposure to the unity nerve center and

Aecision maker. The manager is also charged with

‘designing bis unie' structure, chat pater of formal

{elatonshipe taae detenmines how work 1s 10 De

divided and coordinated.

‘Also, ia his role as resource allocator, the manazer

futhonzes the important decisions of bis unit before

they are implemented. By retaining this power, the

‘manager can ensure chat deesions se interrelated

HI ust pase dough a single brain. To fragment

this power is to encourage discontinuous decision

making and a dijoined state.

‘Tice ase + suuler of interesting fearares about

the managers authonzing others decisions, Fist.

despite the widespread use of capital budgeting pe

‘edures-a means of authorizing various eapital ex-

Dencitures se one me-execusives in ny study made

a great maay authorizvtion decisions on an ad hoe

basis Append, many projects cannot walt or

Sicaply do not have the quantdable costs and bene-

Ses that capieal Budgeeng requires.

Second I found that the chef executives faced in

redibly complex choices, They had to consider the

{pact of each decision on other decisions and on

the organizaon’s strategy. They had co ensure that

the devsion would be seceptable to those who i

‘Duence the organization, as well as ensure that re

sources would not be overextended. They had to

“understand the various costs and benefice as well 26

the feaiiliey of the proposal. They also bad to

consider questions of eming All this was necessary

for the simple approval of someone elses propos

[At the same time, however, delay could lose eime,

‘while quick approval could be il considered and

Guck ejection might discourage the subordinate

Sho had spent months developing a pet proiect.

(One common solution t0 spproving projects is to

pick the maa instead of the proposal. That is, the

Ensnaget authorises those projects presented «0 him

by people whose judgment he trusts. But he cannot

slovays use this simple dodge.

‘The Gaal decisional role is that of negotiotor. Studies

of managerial work at all levels indicate chat man-

Seets spend considerable time im negotistions! the

president ofthe football team is called in to-work

fur a contact with the holdout superstar, the cor

potation peesident leads his company's contingent

fo negotiate a new stk isue, dhe foreman argues

2 plevance problem #9 ies conclusion with the shop

Seber As Lennard Sayles punt i ncgodacons are

{way of fe" forthe sophisiated manages,

“These negodiations ate duties of the manager's job;

perhaps routine, they are not to be shisked. They

can integral part of his jb, for only he has the

horcy t commit organizational resourees in

‘real time,” and only be has the nerve center in

ormation that important negoustions feauie

‘The integrated job

1k shouldbe clear by now thatthe ten roles I have

‘been describing are not eanly separable. In the ter

minalogy of the psychologist chey form a gestalt,

fn integrated whole. No role can be pulled out of

the framework and the job be left inact. For ex

imple, # manager without liaison coneacs lacks

exceral information, As 2 result, be can neither

Siseminace the information his employees need nor

take decisions *hat adequately reflect extemal con-

ditions. a fact, eis 3 peoblem for the new person

{na enanagerial poston, snes he canne make ef

tive decisions unl he bas built up his neework of

contacts

Here lies a clue tothe problems of tim manage

ment" Two of thee people cannot share 2 single

‘anagerial postion unless chey can act a8 one

neiy, This means that they eanaot divide up the

ten roles unless they cam very carefully reintegrate

them. The real ifteuley les with the informational

oles, Unless theze can be full sharing of managerial

information-and, as I pointed out eae, pr

sanly verbalmtesm management breaks down. A

fngle managerial job eannot be axbizanly split, for

‘Grample, into intemal and extemal roles, fr in

formation from both sources must be brought

‘bear on the same decisions.

“To say thatthe en roles form 2 gestalt s not say

hat all manager give equal aitenion to each role

In fut, [fount in may review of the various research

studies that

tales managers seem to spend relatively more of

their sme in the interpersonal roles, presumably 2

feflection of the extrovere nature of the marketing

scuviy,

productlon managers give relatively more atten

tion to the decisional oes, presumably a refection

of theis concern with eficeat work Bow,

soata’ managers spend che most time in the in

ormational roles, since they ae experts who man-

age departments that advise other para of the or.

ganization

[Nevertheless n all eas the interpersonal, informa:

tioaal, and decisional roles remain inseparable

Toward more effective

management

‘What are che messages for management in this de

scription T believe, Arst and foremost, that this

Aeseription of manageral work should prove more

important to manager chan aay prescription they

‘ighe derive from fe That isto say, the mancger't

‘foctiveness i sgnifancly influenced by Bis in-

igh inco is own work. His performance depends

SF how well he understands and responds so the

rea sad dilemmas ofthe job. Thus managers

iho ean be introspective about their work ate ely

abe elective at ther jobs. The ruled Insert on page

So ober 1a gioups of eestudy questions for mae

Shem Some may sound thetozal, none is meant (0

‘be Even though the questions cannoc be answered

Simply, the manager should address them,

Let us take 4 Took 2 dee specific areas of concer.

For the most pare, che managerial logiams—the

‘Atesama of delegation, che database centralized in

tne bain, the problems of working withthe man-

Gpemene scientst~revolve around the verbal nature

GF the managers informacion. There ae great dan-

(ges in ceavalising the organization’ data bank in

he minds of ie managers. When they leave, hey

fae their memory with them. And when subord-

Snes are out of convenient verbal rach of the

‘anaged they are ae an informational disadvantage

1

‘The maneger challenged to find systematic ways

to tare hs peivilegd information. A regular de

biieting session with key subordinates, 2 weekly

memory dump on the dictating machine, the main

{ining ofa diary of portant information for lim-

feed elfculation, or other similar methods may esse

the logjam of work considerably. Time spent dis

eminating tis informacion will be more then re

uined when decisions must be made. Of course,

‘Emme wil raise the quertion of confidentiality But

nansgers would do well to weigh the risks of ex:

posing privileged information against having sub-

Srainates who can make efeccve decisions,

there i a single theme that runs through his

fulcle, ic fs that the pressures of his job dive the

‘ranager to be superdcial ia his ations—ro overload

Fimwelf with work, encourage ineeuption, respond

quickly to every semulus, seek the tangible and

void the abstract, make decisions in small Sacre

iments and do everyting abrsptly.

2

Fete ogcn, the manager ss challenged to deal con

sously wih the pressures of superficiality by ving

Setoas cucusion to che irucs that require i. By

Stepping back from bis tgible bits of information

in order to see e broad pture, and by making we

of analytical impute Although effective managers

hnave to be adept 2 responding quickly to numerous

dnd varying problems, the danger in managerial

‘work is that they will respond to every issue equally

[and shar means abruptly] and that they wil never

trork the tangible bie end pleces of informational

Taput into a comprehensive picture of their world

‘As I noted eater, he manager uses these bits of

information to build models of his word. But che

‘manager can also avail himself ofthe models of the

fetlalina, Economists describe the functioning of

‘market, operations researchers simulate financial

How proceses, and behavioral scientists explain the

‘needs and oats of people. The best ofthese models

‘can be searched out and leamed.

In dealing with complex lsues, che senior mana

‘hes much to gain from a clove relationship with the

‘management scientists of his own organization.

They have something important that he lacks

time to probe complex semves. An eflective working

felationship hinges an the resolution of what a col.

Teague and bave called “the olanning dilemma”

‘Managers have the in‘ormation and the authority;

chalyse have the time and the technology. A sue-

Gestal working telaonship between the wo wil

be effected when the manager leams to share his

information and the anaiyst fears to adapt 9 the

‘managers needs, For the analyst, adaption means

‘worying ess abovt the elegance of the method and

ore about ier apeed and Sebi.

Ieseems to me that analysts can help the top man-

ager especially © schedule his time, feed in analy-

‘ical information, monitor projects under his #u

‘sion, develop models to aid in making chow,

design contingency plans for disturbances that can

be anseipated, and conduct “quick-and-dirty" an

tlysis for those that cannot, Bue there can be no

Cooperation if the analysts are out of the main-

‘ream of the manager’ information low.

3

‘The manager ie challenged to gain contrl of bis

‘own dime by turing obligacons to his advantage

Gnd by timing those things he wishes co do into

Sbligavions, The chief executives of my study ink

Ciated only 32% of their own contacts (and another

SG by mutual agreement]. And yer «0 a consider:

‘ble extent they seemed to control their sme. There

‘were two key factors that enabled chem to do so.

Fics, he manager has to spend so such dime #

‘charging obligations that he were © view th 4

fs jut tha, be would leave no mark on his organiza-

tion, The unsuccessful manager blames failure on

‘Rv cigucions, the effeceve manager cams his ob-

Tehcondto his own advantage. A speech ita chance

eabby for cause, a meeting isa chance to

Send sent depasuucne, «vist fo an important

(iomer ins chance to extract wade information.

second, the manager frees some of his time to do

Shove things that he-perhaps no one else~thinks

Empocant by tuming them into obligations. Free

fim is made, not found, in the manager’ job; i is

Trced into the schedule: Hoping to leave some time

‘pen for eomemplauion or general planning is tan-

Enoune to hoping thae the pressures of the ob wall

fo away. The manager who wants ro innovate ink

Ses 2 project and obligates others to report back

fo hin, te manager who needs cerain environ-

‘Senta information establishes channels that will

Suiomaticlly keep him informed) the manager who

‘hast tour faclives commits himself publicly.

The educators job

inlly,a word about the walning of managers. Our

anagemene schools have done an admirable job

Of wraining the organization’ specialits—manage

Great scientist, marketing reseatehers, accountants,

nd organizational development specialists, Bu for

{he most pare they Bave not eained managers.”

‘Management schools will bein the serious training

‘Shinanagess when skill aiming eakes a serious place

‘ext to eopnaive leaming. Cognitive learning is de

tached and informations, ike reading a book or

Lisening to a lecture. No doube much important

opie mavetal sist be assimilated by che man-

Suerte, Bot cogmiave learning no more makes

SPobanagee than it does 4 swmmes. Toe Later will

frowa the Gast me he jumps ino the water if his

Coach never sakes him oue of the lecture hall, gets

‘hes wet and gives him feedback on his performance,

tn other words, we ae taught a skill ebrough prac

te plus feedback, whether ina real or a simulated

[Shustion, Oue management schools need wo identify

‘he sls managers Ge, select students who show

potential in there sill, put che students into sit

‘ations where there skills canbe practiced, and chen

[pee them systema feedback on thes performance

‘My deseiption of managerial work suggests « num

fer of important managers! shalls~developing peer

felauonships, caving out negotiations, mouvating

Subordinases, resolving confit, establishing infor

mation networks and subseqsently dsseminating

{formation, making decisions in conditions of ex

tueme ambigutey, and allocating sources Above

Ii the manager needs to be inuospecive bout his

Clove sn shat he may conta t earn on the ob.

Many of the manager’ sills can, ia fact be prac

ticed sing techniques dhe ange from cole playing

to videotaping teal meetings. And our management

fchools can endance the encrepreneural sills by

‘esigning programs chat encourage sensible sk take

ing and snnavacin,

No job is mote vital to our socieny than that of

the manager Te is the manager who determines

whether our social institutions serve us well or

whether they squander our talents and resources.

Tels cme to stup avay the folklore about manager"

fl work, and tne to study it realistically so that

‘re can begin the ciiclt ask of making sgificant

Emprovements in its performance

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Solution Guide To Q2 For CA3 (By NG YK) :: AssumptionsDocument2 pagesSolution Guide To Q2 For CA3 (By NG YK) :: AssumptionsAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- W PV LN (Vi/Vf) (0.12 Mpa) X 8 LN (1.5/0.12) 2.424 Mpa M / Min 2.424 X 10 N/M X Litre / 60 Sec 40400 Watt W JH H W/J H 40400/4.2 X 10 9.62 K CalDocument1 pageW PV LN (Vi/Vf) (0.12 Mpa) X 8 LN (1.5/0.12) 2.424 Mpa M / Min 2.424 X 10 N/M X Litre / 60 Sec 40400 Watt W JH H W/J H 40400/4.2 X 10 9.62 K CalAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- 14 2042015Assignment09SolutionDocument4 pages14 2042015Assignment09SolutionAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Bentham TranscriptDocument5 pagesBentham TranscriptAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Original FYP Introd 2011 PDFDocument13 pagesOriginal FYP Introd 2011 PDFAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- I WILL BE HERE - Steven Curtis ChapmanDocument5 pagesI WILL BE HERE - Steven Curtis ChapmanAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding the Introduction ChapterDocument10 pagesUnderstanding the Introduction ChapterAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding the Introduction ChapterDocument10 pagesUnderstanding the Introduction ChapterAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Bible Verses Scavenger HuntDocument2 pagesBible Verses Scavenger HuntAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- TimetableDocument2 pagesTimetableAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Started As An Intern, and He's Not The Only OneDocument12 pagesStarted As An Intern, and He's Not The Only OneAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Career Track at Ministries For Degree, Non-Degree Holders - Teo Chee Hean (TODAY - Mar 10 2015)Document3 pagesCommon Career Track at Ministries For Degree, Non-Degree Holders - Teo Chee Hean (TODAY - Mar 10 2015)Amos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- 52 WorkoutsDocument66 pages52 WorkoutsDaniel PoncePas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Outlook For Energy - ExxonmobilDocument80 pages2016 Outlook For Energy - Exxonmobilrenatogeo14Pas encore d'évaluation

- Response For CoE VideoDocument2 pagesResponse For CoE VideoAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Past Exam Ques and Solution Part 1Document30 pagesPast Exam Ques and Solution Part 1Amos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- HydrostaticsDocument25 pagesHydrostaticsgirish_jagadPas encore d'évaluation

- From Study Book To Learning With Joy For Life (ST - Mar 7 2015)Document4 pagesFrom Study Book To Learning With Joy For Life (ST - Mar 7 2015)Amos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Aspire To Break Through Limiting Beliefs (ST - Sep10 2014)Document2 pagesAspire To Break Through Limiting Beliefs (ST - Sep10 2014)Amos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- A Mission To Change A Nation's AttitudeDocument2 pagesA Mission To Change A Nation's AttitudeAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Tutorial 5Document2 pagesTutorial 5Amos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- CeramicsDocument146 pagesCeramicsAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Degree Holders Have The Edge From The Get-Go (ST - Aug30 2014)Document2 pagesDegree Holders Have The Edge From The Get-Go (ST - Aug30 2014)Amos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- 04.22.2015 Evening Talk by Jean Claude TrichetDocument1 page04.22.2015 Evening Talk by Jean Claude TrichetAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- MA2001 MindmapDocument6 pagesMA2001 MindmapAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Energy-Industry Scholarship (EIS)Document2 pagesEnergy-Industry Scholarship (EIS)Amos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- NTU Accounting Seminar on Flexible Budgeting and Cash FlowDocument1 pageNTU Accounting Seminar on Flexible Budgeting and Cash FlowAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- NTU Accounting Seminar on Flexible Budgeting and Cash FlowDocument1 pageNTU Accounting Seminar on Flexible Budgeting and Cash FlowAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation

- Amos' Sem 2 TimetableDocument1 pageAmos' Sem 2 TimetableAmos YapPas encore d'évaluation