Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Phase 3

Transféré par

api-312995119Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Phase 3

Transféré par

api-312995119Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Running head: INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

Intervention in Homeless Families: Phase 3

Jessica L. Eckmeter

Wayne State University

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

Abstract

Homeless families make up 36% of homeless people. Many problems begin to occur

among both sheltered and unsheltered homeless families including loss of family role and

increased stress for children, leading to behavioral problems. The multiple-family group

weekend retreat intervention addresses these problems among sheltered families, teaching

participants how to cope with stress, communicate better and reaffirm each persons role within

the family unit. This approach utilizes the strengths of each family member, while empower them

to make decisions which can contribute to the betterment of their entire family.

Keywords: homeless, family, intervention, multiple-family group

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

Statement of the Problem

Homelessness among families is a serious problem in the United States today. The

Department of Housing and Urban Development published a report to Congress about

homelessness in the United States which contained statistics about the number of homeless

families. On a given night in January 2013 36% of homeless people represented homeless

families, 86% were sheltered. Among the chronically homeless, families make up 15%. (Henry,

M., Cortes, A., Morris, S., 2013, p. 22-30) There are various organizations aiming to alleviate

family homelessness with knowledge of the various causes. These causes include the lack of

affordable housing, difficulty obtaining living wage jobs, a need for affordable childcare, and

domestic violence.

The causes of family homelessness can be seen and intervened with on both a macro and

micro level. On the macro level, increases in wages, more subsidized housing and affordable or

subsidized childcare could all make the goal of a permanent home more attainable to families

who are currently homeless. On the micro level intervention in domestic violence has the

potential to keep families together, and keep victims out of shelters.

Looking at the root causes of family homelessness can better help in planning

intervention methods both on the local and national level. An illness or accident can be all that it

takes to push an entire family into homelessness. In addition to alleviating the problem of

homelessness, aiming to prevent it for the families that are on the brink of losing their homes can

help bring those numbers down, as such a small percentage of homeless families are chronically

homeless. Education plays a large role in keeping people off of the street and out of shelters.

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

Financial planning, saving and access to resources can prevent this from becoming a problem for

many families.

One of the biggest challenges in relieving homelessness among families is getting the

chronically homeless out of the cycle that makes obtaining stable employment and being able to

support a family so difficult. Once a person is homeless basic needs that can help a parent obtain

employment, such as access to professional clothing, maintaining professional hygiene and

having the rest and food needed to concentrate and successfully interview become growing

hurdles.

Aside from homelessness as a problem in and of itself, the impact this situation has on

families can be damaging to the family unit as a whole. Parental figures have trouble holding

onto their roles as caregivers and providers in a shelter setting, particularly in families that have

both teenage girls and younger children. (Lindsey, 1998)

Research Design

The research design is the plan for a research study. In A Multiple-Family Group

Intervention for Homeless Families: The Weekend Retreat the most accurate way to describe this

research design is a as a pretest-posttest design. Referral to the study by shelter case workers and

directors served as a pretest, with three focal objectives: role clarification, communication, and

decreasing child behavioral problems, and two themes: strengthening families, and families

have fun together. A brief evaluation survey at the end of the retreat was used as a post-test to

measure how successful families felt the retreat was in helping them to deal with stress and feel

positive about themselves, among other variables.

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

Originally the multiple-family group Intervention research plan consisted of meeting with

twenty families weekly over eight weeks, but at the end of the study only six families remained

and the study was reconfigured to consist of a single weekend retreat. This weekend retreat is

the primary focus of the research article, though it is notable that the original research design

failed due to families in the multiple-family group Intervention moving out of shelters for

various reasons.

The weekend retreats were held on Friday evenings from 5:30 PM until 8:00 PM and

continued on Saturday from 9:00 AM until 4:00 PM in a community church centrally located in a

mid-south metropolitan area. (Davey, 2004, p. 327) The specific name of the church and city are

not mentioned in this article.

Sampling

Research participants were recruited by social workers and directors in shelters near the

church in which the weekend retreat was held. Thirty-nine total families, including sixty-two

children participated in five multiple-family group weekend retreats, of which 57% of the

families were African American and 77% had single female parents with a mean average of 1.84

elementary school-age children with an average age of 7.95. (Davey, 2004, p. 327)

The article does not specifically define the sampling method, but from the information

given above the sampling method is a non-probability criterion sample with elements of an

availability/convenience sampling method. Subjects were chosen from those in shelters who met

the criteria of being a family with at least one school aged child. Using sheltered homeless

families as a criteria limited those in the homeless population researchers could choose from.

Measurement

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

The variables in the multiple-family group weekend retreat study were focused on in four

separate sessions and include building trust, identifying family strengths, communication, stress

management, and decision making responsibilities. Within these sessions the examined variables

included parents coping ability, interpersonal interactions and family socialization, and parental

authority and responsibility. Many possible variables were discussed throughout the article, and

specific variables were not clearly stated, though the last three mentioned seemed to be the

primary focus of the study. The changes in these variables were evaluated through a survey at the

end of the retreat evaluating the opinions of parents and children participating in the study.

Data Collected

Data collected focused on the attitudes of family members upon completion of the

weekend retreat. An evaluative survey near the end of the weekend was the primary means in

which data was collected, though this was interpreted by the social workers and volunteer social

work students who also observed the behaviors and impact of the retreat activities.

Participants reported favorable opinions on how activities within the retreat helped them

to cope with stress and feel positive about themselves. The primary finding in this study is that

social support is a key factor in reducing anxiety, isolation and helplessness in homeless families.

Through working with groups homeless families were better able to learn coping and stress

management skills, define family roles, and increase communication within their own families.

Ethics and Cultural Considerations

The multiple-family group weekend retreat is an effective method for helping parents

reclaim their role, but does not address the problem of homelessness as a whole. It does not

alleviate homelessness, but it does prepare the family to have better interaction, communication

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

and role definition both in the shelter system and for their future once they are able to find

housing and employment. Better functioning in the home can improve child behavior and

minimize problems that contribute to unemployment.

The intervention method is sensitive to the unique cultural characteristics of homeless

families as it takes into consideration the problems specific to this group and empowers family

members to take control of the factors in the family in which they can change. This intervention

method also takes the pressure from individual members of homeless families by discussing the

responsibility of each member in a group setting that allows families to gain support from each

other. It utilizes role-playing rather than requesting personal examples of both destructive and

constructive behaviors, which is sensitive to homeless family members needs.

Ethical concerns were not mentioned in this article at all, though it is safe to say that as

the weekend retreat staff was comprised of entirely social workers and the journal that published

the article is published on behalf of the NASW, the NASW code of ethics was likely followed.

Informed consent was not mentioned, but a briefing was implied to have occurred in Section

One: Building Trust Identifying Family Strengths where Timothy L. Davey mentions that the

families were helped to identify some of the concerns participants wanted to work on during the

retreat. No harm was done to any of the participants in the study, and participants were invited,

not mandated to attend the retreat, both being ethical requirements for research.

Results and Implications

This intervention method addresses the problem of damage to a family unit caused by

homelessness, but does not address the causes of homelessness directly. The multiple-family

group weekend retreat intervention alleviates role ambiguity, teaches families how to work

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

together as a unit, in a setting that typically results in reliance on outside sources of support, and

teaches family members better ways to cope with and prevent stress. These benefits to

participants can help them stay emotionally healthy during homelessness and once they are out

of the shelter may help them to stay out of the shelter. These benefits can increase confidence

and a sense of empowerment to homeless family members, both of which are beneficial when

seeking employment, as unemployment is one of the leading causes of family homelessness.

The activities in this intervention contribute to alleviation of homelessness. In session

one, families are reminded that they must build on their strengths in order to create positive

change in their lives. Session two helped participants focus on communication skills which will

help parents to engage in their childrens lives, keeping them away from the habits that can

perpetuate homelessness or make it more difficult to recover from. Session three taught

participant families how to identify stress as an indicator that change must occur (Davey, 2004,

p. 328) and how working together can help solve the problems that lead to stress. Session four

brought attention to the shared responsibility of every family member in making decisions that

help the family, helping each member to understand the important role they play.

Practitioners leading this intervention would need to have experience in working with

groups and people of all ages. This study had several social workers collaborating including a

social worker from a school homeless education program and a clinical social worker. Each

social worker brought different experiences that were important in making this intervention

successful. Skill and experience in working with children is necessary to conduct an intervention

like this, but also an ability to work with parents in a manner that empowers them rather than

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

demeans them. Experience in working with shelters and the impoverished would be a strong tool

in a social workers arsenal for this intervention as well.

The agency that I will be doing my field placement with in the fall is a shelter that only

works with victims of domestic violence. There are many barriers to making an intervention such

as this one work in such an agency, primarily the risk of abuse to members of the family trying to

flee an abusive family member. The first session in this intervention, building trust, could be a

much bigger hurdle to an abuse victim than it would members of a family who are homeless

under different circumstances. Scheduling may also prove to be a barrier in this setting, as the

homeless who are employed likely work a lower paying job with atypical hours.

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

10

References

Davey, T. (2004). A multiple family group intervention for homeless families: the weekend

retreat. Health & Social Work, 29(4), 326-329.

Henry, M., Cortes, A., Morris, S. (2013) The 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report

(AHAR) to Congress. Retrieved from

https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/ahar-2013-part1.pdf

Lindsey, E. (1998). The Impact of Homelessness and Shelter Life on Family Relationships.

Family Relations, 47(1240), 243-243. Retrieved

http://web.ebscohost.com.proxy.lib.wayne.edu/ehost/detail/detail?sid=a5adae0d-5fcb4fc7-acd2-048135ad688e

%40sessionmgr113&vid=3&hid=115&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1

zaXRl#db=swh&AN=65322

Onolemhemhen, D. (2015). Ethics and politics of social work researchdd. [PowerPoint slides].

Retrieved from

https://blackboard.wayne.edu/webapps/blackboard/execute/displayIndividualContent?

course_id=_1104448_1&content_id=_4982003_1&mode=reset

Onolemhemhen, D. (2015). Key concepts in sampling. [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from

https://blackboard.wayne.edu/webapps/blackboard/execute/displayIndividualContent?

course_id=_1104448_1&content_id=_5061416_1&mode=reset

INTERVENTION IN HOMELESS FAMILIES: PHASE 3

Onolemhemhen, D. (2015). Measurement. [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from

https://blackboard.wayne.edu/webapps/blackboard/execute/displayIndividualContent?

course_id=_1104448_1&content_id=_5030323_1&mode=reset

Onolemhemhen, D. (2015). Research design. [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from

https://blackboard.wayne.edu/webapps/blackboard/execute/displayIndividualContent?

course_id=_1104448_1&content_id=_5042877_1&mode=reset

Rubin, A., Babbie, E. (2013). Essential Research Methods for Social Work (3rd ed.). Belmont,

CA: Brooks/Cole.

11

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Experience of Grandparents Raising GrandchildrenDocument24 pagesExperience of Grandparents Raising Grandchildrenjanielovescarilla escarilla100% (1)

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Parenting and Parent-Child RelationshipsD'EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Parenting and Parent-Child RelationshipsPas encore d'évaluation

- Empathy, Childhood Trauma and Trauma History as a ModeratorD'EverandEmpathy, Childhood Trauma and Trauma History as a ModeratorPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Model of Family TherapyDocument5 pagesStrategic Model of Family Therapymiji_ggPas encore d'évaluation

- Interventions For Families of Substance AbuseDocument7 pagesInterventions For Families of Substance Abuseapi-284406278Pas encore d'évaluation

- Family Climate and The Role of The The AdolescentDocument10 pagesFamily Climate and The Role of The The AdolescentRoxana MacoviciucPas encore d'évaluation

- Families and Educators Together: Building Great Relationships that Support Young ChildrenD'EverandFamilies and Educators Together: Building Great Relationships that Support Young ChildrenPas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: SINGLE MOTHERS 1Document21 pagesRunning Head: SINGLE MOTHERS 1Harda Mgs100% (3)

- Hear Our Voices!: Engaging in Partnerships that Honor FamiliesD'EverandHear Our Voices!: Engaging in Partnerships that Honor FamiliesPas encore d'évaluation

- Rationale for Child Care Services: Programs vs. PoliticsD'EverandRationale for Child Care Services: Programs vs. PoliticsPas encore d'évaluation

- Positive Parenting with a Plan: The Game Plan for Parenting Has Been Written!D'EverandPositive Parenting with a Plan: The Game Plan for Parenting Has Been Written!Évaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (2)

- The CRAF-E4 Family Engagement Model: Building Practitioners’ Competence to Work with Diverse FamiliesD'EverandThe CRAF-E4 Family Engagement Model: Building Practitioners’ Competence to Work with Diverse FamiliesPas encore d'évaluation

- Valuing Children: Rethinking the Economics of the FamilyD'EverandValuing Children: Rethinking the Economics of the FamilyPas encore d'évaluation

- Family Case StudyDocument51 pagesFamily Case StudyCeledonio Jumalon Montefalcon50% (2)

- Navigating Family Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Middle-Aged WomenD'EverandNavigating Family Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Middle-Aged WomenPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychometric Properties of The Family Support Scale With Head Start FamiliesDocument10 pagesPsychometric Properties of The Family Support Scale With Head Start FamiliesMahendra MJPas encore d'évaluation

- Signature AssignmentDocument15 pagesSignature Assignmentapi-302494416Pas encore d'évaluation

- SW 3810 Accessing and Using Evidence in Social Work Practice-Phase IIIDocument7 pagesSW 3810 Accessing and Using Evidence in Social Work Practice-Phase IIIapi-286703035Pas encore d'évaluation

- Family Strategies: Practical Tools for Treating Families Impacted by AddictionD'EverandFamily Strategies: Practical Tools for Treating Families Impacted by AddictionPas encore d'évaluation

- He Looks Like Me: An evidence based guide for teachers mentoring African American BoysD'EverandHe Looks Like Me: An evidence based guide for teachers mentoring African American BoysPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychometric Properties of The Family Support Scale With Head Start FamiliesDocument10 pagesPsychometric Properties of The Family Support Scale With Head Start FamiliesPriandhita AsmoroPas encore d'évaluation

- Family AssessmentDocument13 pagesFamily Assessmentblast211140% (5)

- Essay May IVDocument16 pagesEssay May IVMuhamad BurhanudinPas encore d'évaluation

- Fowler2017 - Term Paper Shit PDFDocument6 pagesFowler2017 - Term Paper Shit PDFAnsalPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis Research PaperDocument16 pagesAnalysis Research Paperapi-560013194Pas encore d'évaluation

- Manabat, Michelle Marie F., Pabustan, Bryant M., Tolentino, Lorenz Angelo UDocument5 pagesManabat, Michelle Marie F., Pabustan, Bryant M., Tolentino, Lorenz Angelo UTimothyPas encore d'évaluation

- Achieving Permanence for Older Children and Youth in Foster CareD'EverandAchieving Permanence for Older Children and Youth in Foster CarePas encore d'évaluation

- Support, Communication, and Hardiness in Families With Children With DisabilitiesDocument17 pagesSupport, Communication, and Hardiness in Families With Children With DisabilitiesAnnisa Dwi NoviantyPas encore d'évaluation

- As One." - UnknownDocument6 pagesAs One." - UnknownJashtine JingcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ajot ManuscriptDocument30 pagesAjot Manuscriptapi-469965611Pas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding and Addressing Girls’ Aggressive Behaviour Problems: A Focus on RelationshipsD'EverandUnderstanding and Addressing Girls’ Aggressive Behaviour Problems: A Focus on RelationshipsPas encore d'évaluation

- Walsh - Family TherapyDocument26 pagesWalsh - Family TherapyPablo Vasquez100% (1)

- Chapter Iv - DiscussionDocument3 pagesChapter Iv - DiscussionstaaargirlPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 SAGE Journal ArticlesDocument3 pagesChapter 2 SAGE Journal ArticlesBill BensonPas encore d'évaluation

- TaylorConger 2017 Child - DevelopmentDocument10 pagesTaylorConger 2017 Child - DevelopmentKren WolfverPas encore d'évaluation

- Supporting Families Experiencing Homelessness: Current Practices and Future DirectionsD'EverandSupporting Families Experiencing Homelessness: Current Practices and Future DirectionsPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Work With Homeless Mothers A Strength-BasedDocument12 pagesSocial Work With Homeless Mothers A Strength-BasedGiovanna CinacchiPas encore d'évaluation

- RRLDocument12 pagesRRLEmilyne Joy Mendoza CabayaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender, Updated EditionD'EverandThe Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender, Updated EditionÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (14)

- Making It Better: Activities for Children Living in a Stressful WorldD'EverandMaking It Better: Activities for Children Living in a Stressful WorldÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (3)

- Parental Monitoring of Adolescents: Current Perspectives for Researchers and PractitionersD'EverandParental Monitoring of Adolescents: Current Perspectives for Researchers and PractitionersPas encore d'évaluation

- Family AssessmentDocument31 pagesFamily AssessmentAmy Lalringhluani ChhakchhuakPas encore d'évaluation

- Messages From Home: The Parent-Child Home Program For Overcoming Educational DisadvantageD'EverandMessages From Home: The Parent-Child Home Program For Overcoming Educational DisadvantagePas encore d'évaluation

- Fraud in the Shadows of our Society: What is Unknown About Educating is Hurting Us AllD'EverandFraud in the Shadows of our Society: What is Unknown About Educating is Hurting Us AllPas encore d'évaluation

- Clinical Social Work Practice with Children and FamiliesD'EverandClinical Social Work Practice with Children and FamiliesPas encore d'évaluation

- Compiled FCA 103Document151 pagesCompiled FCA 103Bryan YanguasPas encore d'évaluation

- Bueno&Nabor SWResearchDocument63 pagesBueno&Nabor SWResearchClaire BuenoPas encore d'évaluation

- Catching a Case: Inequality and Fear in New York City's Child Welfare SystemD'EverandCatching a Case: Inequality and Fear in New York City's Child Welfare SystemÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- I Can Be Me: A Helping Book for Children of Alcoholic ParentsD'EverandI Can Be Me: A Helping Book for Children of Alcoholic ParentsPas encore d'évaluation

- Children Living in Transition: Helping Homeless and Foster Care Children and FamiliesD'EverandChildren Living in Transition: Helping Homeless and Foster Care Children and FamiliesPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Parenting Styles and Effects On Children - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument4 pagesTypes of Parenting Styles and Effects On Children - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfAna BarbosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Eckmeterresume 2016Document2 pagesEckmeterresume 2016api-312995119Pas encore d'évaluation

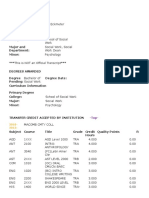

- Advising Copy TranscriptDocument5 pagesAdvising Copy Transcriptapi-312995119Pas encore d'évaluation

- Eckmeter Mi CertificateDocument1 pageEckmeter Mi Certificateapi-312995119Pas encore d'évaluation

- Letter of Reference PortfolioDocument2 pagesLetter of Reference Portfolioapi-312995119Pas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: FAMILY OF ORIGIN 1Document5 pagesRunning Head: FAMILY OF ORIGIN 1api-312995119Pas encore d'évaluation

- Catalogu PDFDocument24 pagesCatalogu PDFFer GuPas encore d'évaluation

- Case LawsDocument4 pagesCase LawsLalgin KurianPas encore d'évaluation

- Ebook4Expert Ebook CollectionDocument42 pagesEbook4Expert Ebook CollectionSoumen Paul0% (1)

- Climate Resilience FrameworkDocument1 pageClimate Resilience FrameworkJezzica BalmesPas encore d'évaluation

- Career Development Cell: Kamla Nehru Institute of TechnologyDocument1 pageCareer Development Cell: Kamla Nehru Institute of TechnologypiyushPas encore d'évaluation

- Aud Prob Compilation 1Document31 pagesAud Prob Compilation 1Chammy TeyPas encore d'évaluation

- Signal Man For RiggerDocument1 pageSignal Man For RiggerAndi ZoellPas encore d'évaluation

- MBA621-SYSTEM ANALYSIS and DESIGN PROPOSAL-Bryon-Gaskin-CO - 1Document3 pagesMBA621-SYSTEM ANALYSIS and DESIGN PROPOSAL-Bryon-Gaskin-CO - 1Zvisina BasaPas encore d'évaluation

- Adrian Campbell 2009Document8 pagesAdrian Campbell 2009adrianrgcampbellPas encore d'évaluation

- MANUU UMS - Student DashboardDocument1 pageMANUU UMS - Student DashboardRaaj AdilPas encore d'évaluation

- Oxford University Colleges' ProfilesDocument12 pagesOxford University Colleges' ProfilesAceS33Pas encore d'évaluation

- Urban Planning PHD Thesis PDFDocument6 pagesUrban Planning PHD Thesis PDFsandracampbellreno100% (2)

- Education Rules 2012Document237 pagesEducation Rules 2012Veimer ChanPas encore d'évaluation

- Summarydoc Module 2 LJGWDocument14 pagesSummarydoc Module 2 LJGWKashish ChhabraPas encore d'évaluation

- Boone Pickens' Leadership PlanDocument2 pagesBoone Pickens' Leadership PlanElvie PradoPas encore d'évaluation

- City Development PlanDocument139 pagesCity Development Planstolidness100% (1)

- Dax CowartDocument26 pagesDax CowartAyu Anisa GultomPas encore d'évaluation

- Cover LetterDocument1 pageCover Letterapi-254784300Pas encore d'évaluation

- Applicability of ESIC On CompaniesDocument5 pagesApplicability of ESIC On CompaniesKunalKumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Trends and Challenges Facing The LPG IndustryDocument3 pagesTrends and Challenges Facing The LPG Industryhailu ayalewPas encore d'évaluation

- FILL OUT THE Application Form: Device Operating System ApplicationDocument14 pagesFILL OUT THE Application Form: Device Operating System ApplicationNix ArcegaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 18Document24 pagesChapter 18Baby KhorPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 - Comment Review SheetDocument1 page11 - Comment Review SheetMohamed ShokryPas encore d'évaluation

- (Digest) Marcos II V CADocument7 pages(Digest) Marcos II V CAGuiller C. MagsumbolPas encore d'évaluation

- Multicast VLAN CommandsDocument8 pagesMulticast VLAN CommandsRandy DookheranPas encore d'évaluation

- Gyges RingDocument1 pageGyges RingCYRINE HALILIPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3Document56 pagesChapter 3percepshanPas encore d'évaluation

- LWB Manual PDFDocument1 pageLWB Manual PDFKhalid ZgheirPas encore d'évaluation

- CPAR FLashcardDocument3 pagesCPAR FLashcardJax LetcherPas encore d'évaluation

- Art10 PDFDocument10 pagesArt10 PDFandreea_zgrPas encore d'évaluation