Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Running Head: Adolescent Contraception 1

Transféré par

api-314835119Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Running Head: Adolescent Contraception 1

Transféré par

api-314835119Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

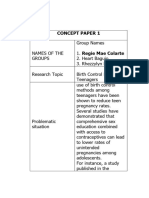

Running head: ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

Adolescent Contraception Counseling and Management for Long-Acting Reversible

Contraception: A Systematic Review

Rachel Soles

University of Detroit Mercy

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

2

Abstract

Adolescent pregnancy is an important public health issue in the United States, with 750,000

pregnancies occurring yearly, approximately 80% of which are unintended (Finer & Zolna, 2011;

Sheeder, Tocce, Stevens-Simon, 2008). Adolescents are more likely than older women to use

contraceptive methods that require user adherence and follow-up visits with health care providers

(Guttmacher Institute, 2014) and less likely to use methods that both have higher efficacy and do

not require user adherence, long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs). In recent years,

professional organizations have published guidelines recommending that LARCs be considered

as first-line options for contraception in adolescents (American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists, 2012; American Academy of Pediatrics, 2014), however rates of LARC use in

adolescents remain low (Guttmacher Institute, 2014). Studies have suggested that clinician

counseling is the most important predictor of whether a young woman attempts a method of

contraception (Harper et al., 2013) and that clinicians may not be prepared to counsel adolescents

about LARCs due to lack of knowledge, misinformation about contraindications or adverse

effects, and beliefs about the appropriateness of LARCs for adolescents (Kohn, Hacker,

Rouselle, & Gold, 2012; Rubin, Davis & McKee, 2013). This systematic review found a number

of knowledge gaps and misconceptions surrounding the provision of LARCs to adolescents and

as a result, identified areas where clinicians would benefit from interventions to increase

knowledge and enhance efficacy in LARC counseling and management.

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

Adolescent Contraception Counseling and Management for Long-Acting Reversible

Contraception: A Systematic Review

Despite recent declines, the adolescent pregnancy rate in the United States remains an

important public health issue. The United States consistently has the highest adolescent

pregnancy rate of any industrialized country, with approximately 750,000 reported each year

(Finer & Zolna, 2011; Sheeder, Tocce, Stevens-Simon, 2008). Moreover, while unintended

pregnancy rates among women with family income greater than 200% of the federal poverty

level have declined significantly, unintended pregnancy rates among women with family income

at or below the federal poverty level have stagnated or even risen slightly (Guttmacher Institute,

2013). At least two-thirds of unintended births are paid for with public insurance programs such

as Medicaid, resulting in estimated annual public expenditures of at least $12.5 billion

(Guttmacher Institute, 2013). Adolescents experiencing pregnancy are less likely to finish high

school, or ever have steady employment and are more likely to receive public assistance

compared with peers who delay childbearing (Fuller, 2007).

Sixty-two percent of United States women of childbearing age use contraception of some

sort, including combined hormonal methods (pill, patch, ring), male or female condoms, male or

female sterilization, injectable, implant, fertility awareness method, withdrawal, or intrauterine

device (Guttmacher Institute, 2013). Nineteen percent of women use contraception

inconsistently or incorrectly and account for 43% of all unintended pregnancies. (Guttmacher

Institute, 2013). Approximately 16% of all women do not use contraception at all for at least one

month in a year and account for 52% of all unintended pregnancies. Women who use

contraception consistently, or who report that they do, account for just 5% of unintended

pregnancies. While this data does not specifically reflect teen behaviors, research suggests that

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

approximately 80% of all adolescent pregnancies are unintended (Finer & Zolna, 2011). A

reasonable inference from this data is that most teens that experience unintended pregnancy have

not been using contraception consistently or correctly.

Adolescents are using contraception at higher rates than in the past; 78% of females used

contraception at coitarche compared with 48% in 1982 (Guttmacher Insitute, 2014). Adolescent

women, however, are more likely to use methods which require careful user adherence such as

condoms and oral contraceptives, compared with women in their twenties and thirties

(Guttmacher Institute, 2014). This is likely due, in large part, to teen choice as well as ease of

access, but studies have suggested that many clinicians caring for teens may be less likely to

recommend methods that have both higher efficacy and do not require careful adherence e.g.

primarily long-acting reversible contraceptives [LARCs] such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and

hormonal contraceptive implants (Kohn, Hacker, Rouselle, & Gold, 2012; Rubin, Davis &

McKee, 2013). Just 4% of teens who use contraception use LARCs despite studies which

suggest that when financial barriers are removed and evidence-based counseling is given, 60% of

adolescents choose LARCs (Greenberg, Makino, & Coles, 2013). Financial barriers as well as

practical barriers involving access remain an important issue for adolescents, but the variable that

are is most sensitive to provider action is the provision of counseling and research suggests that it

is the most important predictor of whether young women attempt a contraceptive method

(Harper et al., 2013).

Clinicians and family planning nurses may not be prepared to counsel teens about

LARCs due to lack of knowledge, misinformation about contraindications or adverse effects, and

beliefs about the appropriateness of LARCs for adolescents (Kohn, Hacker, Rouselle, & Gold,

2012; Rubin, Davis & McKee, 2013). Clinician misconceptions about LARCs, particularly

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

IUDs are likely due in part to the history of one IUD, the Dalkon Shield, which was withdrawn

from use in 1974, and was associated with significant adverse effects including pelvic

inflammatory disease (PID), high failure rates, and spontaneous septic abortion, among others

(Hubacher, 2002). In 1998, when IUDs were reintroduced to the United States with the copper

IUD, initial labeling restricted use to multiparous women (Tyler et al., 2012). In 2005, the

United States Food and Drug Administration revised the labeling for the copper IUD to allow use

in nulliparous women (Tyler et al., 2012). However, as recently as 2006, nulliparity and nonmonogamous relationships, characteristics more common in adolescents than in older women

(Fuller, 2007), were listed as contraindications for use of an IUD in peer-reviewed publications

(Paladino, Blenning, & Judkins, 2006). The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers

for Disease Control (CDC) also revised the medical eligibility criteria for adolescent use of IUDs

to benefits generally outweigh risks in 2005, however it has taken time for these revised

criteria to shape practice recommendations (CDC, 2010).

In 2012, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published a

Committee Opinion guiding clinicians to consider LARCs as first-line contraception for

adolescents. The American Academy of Pediatrics followed suit in September 2014, publishing

a Policy Statement with similar guidance. Clinician attitudes and practices do not yet clearly

reflect these recommendation statements.

Over 65% of nurse practitioners (NPs) work in family practice, pediatrics, and womens

health (American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 2014) and may reasonably expect to

encounter adolescent clients seeking contraception. Nurses working in health departments and in

primary care are also in the position to provide contraception counseling to teens. NPs and

nurses working in these settings have the opportunity to develop trusting relationships with their

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

adolescent clients and ensure that adolescents make informed decisions about contraception

(Fuller, 2007). It is imperative that nurses in these roles are competent in providing counseling

for all contraceptive choices, including LARCs.

Research question:

What are current clinician (e.g. NP, nurse midwife, physician assistant (PA), and physician)

attitudes and practices in adolescent contraception counseling for and management of LARCs?

Search Strategy

The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PubMed

databases were searched using the keywords: long acting contraception, adolescent, and

attitudes. The search was limited to articles published after 2009. Reference lists of identified

articles were used to identify additional relevant studies. Inclusion criteria were research studies

that focused on provider practices, beliefs, and attitudes about LARC use in adolescents.

Exclusion criteria were studies that focused on practical, logistical, or administrative barriers to

LARC use in adolescents. Seven studies were evaluated and are summarized in Table A.

Literature Review

Seven studies were analyzed for this review, five quantitative studies and two qualitative

studies. All examined clinician attitudes toward prescribing long-acting reversible contraception.

Some studies additionally examined actual counseling and prescribing practices.

Biggs, Harper, Malvin and Brandis (2014) conducted a cross-sectional survey of medical

directors and supervisory clinicians at California family planning clinics in order to determine

factors that influenced the decision to provide long-acting reversible contraception. The

researchers used probability sampling to select 1,020 recipients of 2,168 potentially eligible sites

where sites serving greater numbers of clients had a higher probability of inclusion. A survey

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

was mailed to the medical director or supervising clinician at selected sites, as well as follow-up

mailings, emails, and telephone calls for initial non-respondents. 640 surveys were received for

a 68% response rate. Forty-nine surveys were eliminated either for being completed by a nonclinician or due to no recent clinic family planning activity which resulted in 587 surveys used

for evaluation. Respondents included 448 physicians, 95 NPs, 32 PAs, and 12 nurse midwives.

Researchers created the survey based on previous research about provider beliefs about LARCs.

Respondents were given a list of 11 patient characteristics and asked to determine which LARC

method (hormonal IUD, copper IUD, hormonal contraceptive implant), if any, would be

appropriate for the patient.

Approximately 20% of respondents reported that IUDs were inappropriate for

adolescents and just 8% reported that hormonal contraceptive implants were inappropriate for

adolescents. Approximately 26% of respondents reported that having a history of PID was a

contraindication for an IUD with just 4% believing that having a history of PID was a

contraindication for a hormonal contraceptive implant. Twenty percent of respondents believed

that a history of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the past two years was a

contraindication for an IUD while just 4% believed it was a contraindication for a hormonal

contraceptive implant. A significant majority of all respondents (93%) agreed that IUDs were

generally safe. On-site provision of LARCs was associated with higher knowledge levels about

LARCs and with likeliness to recommend LARCs.

Harper et al. (2013) surveyed a random representative sample of NPs across the United

States regarding LARC counseling and provision practices. The researchers sought to survey

approximately 600 primary care NPs and 600 womens health NPs. For purposes of the study,

primary care NPs were identified as working in either family practice, adult medicine, or primary

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

care and womens health NPs were defined as working in either womens health, reproductive

health, or obstetrics and gynecology. The samples were generated using random numbers and

the Verispan national database of NPs. Twenty-one duplicate names were eliminated and 1179

surveys were mailed via priority mail with a $20 incentive. Eligibility criteria for respondents

included spending a majority of time in direct patient care and providing family planning

services. After exclusion of ineligible respondents, 586 eligible respondent surveys (224 primary

care NPs and 360 womens health NPs) were reviewed for a 69% response rate after removing

ineligible respondents from the denominator.

The researchers used a survey developed using items validated in previous studies

examining clinician attitudes and behaviors surrounding LARCs as well as from qualitative

clinician interviews. The researchers used a four point Likert scale for self-report of frequency

of counseling patients for LARCs as well as scales to evaluate knowledge and attitudes

surrounding LARCs. The data was evaluated both for overall clinician knowledge as well as

differences between primary care and womens health NPs. Demographically, the groups were

statistically similar; the mean age of respondents was 50 (sd: 9.9), 96% were female, and 88%

were white. Primary care NPs were significantly less likely to counsel about IUDs (odds ratio .

49, 95% CI 0.23-0.72). Primary care NPs also had lower levels of knowledge about IUD

eligibility generally with 55% believing that nulliparity was a contraindication for IUD use, 71%

believing that a history of having an STI in the past two years was a contraindication, and 89%

believing that a history of PID was a contraindication. Twenty-nine percent of primary care NPs

believed that adolescents were candidates for LARCs compared with 51% of womens health

NPs.

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

Kohn, Hacker, Roussette, and Gold (2012) conducted a quantitative descriptive study of

New York City based School-Based Health Center (SBHC) staff including clinicians and nonclinicians. The researchers were primarily concerned with assessing knowledge and attitude

about IUDs. The researchers used a 36-item self-administered survey provided to SBHC staff

prior to attendance at a mandatory training for a reproductive health initiative. The survey was

modeled after an existing instrument used to assess primary care physician knowledge and

attitudes of IUDs. The survey contained seven questions designed to assess knowledge of IUDs

and nine questions where respondents rated the likelihood of recommending an IUD with a given

clinical scenario (none of which represented contraindications for IUD use) using a Likert scale.

One-hundred sixty-two out of 180 total attendees completed the survey (90% response rate).

Respondents included 69 clinicians (32 NPs, 19 pediatricians, 11 PAs, three family practice

physicians, and four unidentified clinicians) and 93 non-clinician staff including social workers,

health educators, medical assistants and other support staff. The researchers did not provide a

rationale for the inclusion of non-clinician staff, few of whom would be expected to play a direct

role in counseling or provision of IUDs. Respondents were predominately female (91%) and had

a mean age of 40.5 years.

In the knowledge assessment, the lowest clinician scores were reported in a question

concerning long-term risks of PID, with just 55% of clinicians correctly identifying that IUDs do

not increase long-term risks of PID. Additionally, 59% of clinician correctly identified that IUDs

do not need to be placed during menstruation. In the likelihood of recommending an IUD

section, 31% of clinicians reported that they would be somewhat or very likely to recommend an

IUD to someone with a history of ectopic pregnancy. Thirty-four percent of clinicians were

likely to recommend an IUD to someone not in a monogamous relationship and 37% of

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

10

clinicians reported that they would be likely to recommend an IUD both to someone with a

recent history of an STI and who had an abnormal pap smear in the last year without a

colposcopy follow-up. Sixty-five percent of clinicians reported that they were somewhat or very

likely to recommend IUDs to adolescents. Interestingly, although 77% of all participants

correctly identified that IUDs were safe for adolescents, 18% reported that they were not likely

to recommend them for adolescents. In this study, for both clinicians and non-clinicians, the

relationship between level of knowledge of IUDs and likelihood of recommending was positive

and statistically significant (r=.41, p<.01).

Madden, Allsworth, Hladky, Secura, and Peipert (2010) conducted a quantitative crosssectional study of 137 Saint Louis obstetricians-gynecologists to evaluate clinician willingness to

insert an IUD and knowledge of side effects of IUDs. Two hundred and fifty potential

participants were randomly selected using phone book listings, web searches, and faculty listings

of obstetricians-gynecologists in the greater Saint Louis area. They were mailed (regular mail or

on-line email?) a survey created by the researchers for this study and pretested by the clinician

researchers. One hundred and thirty seven respondents (54.8% response rate) received a $20

gift card. All respondents were English-speaking, practicing in the city of Saint Louis or Saint

Louis County. Gender of study participants was not reported, however 85% of respondents were

white, and approximately 85% completed residency before 1999. Sixty-two percent of

respondents believed that IUDs were an appropriate contraceptive choice for nulliparous women.

Just 31% of respondents believed that IUDs were appropriate for adolescents. Nearly 37% of

respondents would be willing to recommend an IUD in a client that had PID in the previous five

years, and 36.5% of respondents would be willing to recommend an IUD for patients in nonmonogamous relationships.

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

11

Vaaler, Kalanges, Fonseca, and Castrucci (2012) conducted a quantitative cross-sectional

survey of clinicians at Title X clinics in Texas to assess provider attitudes towards provision of

LARCs, and to detect differences in attitudes and practice among rural and urban clinicians. The

researchers used the Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Survey, emailing it first to directors

of 74 agencies that receive Title X funding in Texas. The directors were instructed to forward the

survey to all site clinicians (estimated 224). The researchers received and evaluated 96 survey

respondents (43% response rate). Ninety-two percent of survey respondents were female and

66% were white. The authors did not report the types of providers surveyed in the demographic

information. Opinions and practices surrounding LARC recommendations were examined as

well as knowledge level about specific benefits of LARC methods. Across all providers, 68%

would recommend LARCs for adolescent clients, while 86% would recommend for clients 20-24

and 89% would recommend for clients 25-34. Although the researchers asked respondents some

questions to differentiate attitudes towards the LARC methods separately (IUDs and hormonal

contraceptive implants), attitudes and likeliness to recommend were not examined for the

methods separately.

Differences in LARC recommendation tendencies between urban and rural providers

were primarily related to administrative and financial barriers. Overall, respondents had

relatively high levels of knowledge about some of the benefits of hormonal contraceptive

implants targeted in the study including that they are effective for up to three years (82% of

respondents correct) and that they are an option for women who cannot use estrogen-containing

methods (78% of respondents correct). Respondents had a lower level of knowledge about how

soon users of the method could expect to return to fertility after the method is discontinued (51%

of respondents correct) and that smoking is not a contraindication (48% of respondents correct).

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

12

The researchers did not report exact numbers but found that some providers stated in open-ended

question responses that client history of having an STI or history of PID was a contraindication

to insertion of an IUD.

Kavanaugh, Frohwirth, Jerman, Popkin, and Ethier (2013) conducted a qualitative study

designed to identify provider and client perceptions of LARCs, perceived advantages and

disadvantages, and barriers to use. The researchers conducted telephone interviews of 20 family

planning program directors. From the information gathered in these interviews, six target sites

were identified: three with high rates of LARC use and three with low rates of LARC use. The

researchers then conducted a focus group session at each of the six identified sites with five to

eight staff members present for each focus group including clinicians and non-clinicians such as

educators, medical assistants and receptionists. Clinic clients were subsequently interviewed for

their perception of LARCs. Themes were identified including that although staff did not believe

being a teen was a disqualifying factor for LARC use, characteristics such as having multiple

partners and being nulliparous were viewed with concern for LARC use. In addition, staff were

concerned that young clients who used a LARC would have decreased interactions with clinic

staff, which represented decreased opportunities to discuss other aspects of reproductive health,

including emphasizing condom use.

Rubin, Davis, and McKee (2013) conducted a qualitative descriptive study to assess

physician capability, opportunity, and motivation to provide LARCs to adolescents. The study

sample consisted of a purposive sample of New York City based physicians, including 10

pediatricians, nine family medicine physicians, and nine obstetricians-gynecologists. The

participants were interviewed by telephone by a physician researcher and recordings transcribed

for analysis by two physician researchers. The researchers identified common themes as well as

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

13

significant differences across provider type. The researchers used an interpretive conceptual

model to organize themes into the categories: capability, opportunity, and motivation. Physicians

were largely found to practice what they learned in residency, particularly with respect to

eligibility criteria, despite changes in guidelines and recommendations. Many providers did not

counsel nulliparous women about LARCs. Many providers were concerned about confidentiality

and consent issues with LARCs and adolescents. Some pediatricians felt uncomfortable

counseling about contraception at all and referred these patients to other clinics. Some providers

were concerned that the use of LARCs would tend to decrease condom use and some believed

that IUDs increased the risk of infection.

Critical Appraisal of the Evidence

Providers across all studies indicated practices, beliefs, or attitudes that decrease the

likelihood of provision of LARC methods to adolescents, despite robust information about their

safety and efficacy for this population. In addition, clinicians across these studies evidenced

some knowledge deficits about LARC methods, particularly regarding eligibility criteria,

contraindications, and potential adverse effects.

Clinicians across four of the reviewed studies reported that they were less likely to

recommend LARC methods to adolescents than older clients (Harper et al.; Kohn et al., 2012;

Madden et al., 2010; Vaaler et al., 2012). Clinicians in the qualitative studies reported concerns

about provision of LARCs to adolescents including concerns about consent and confidentiality

and concerns that use of LARCs would decrease the likelihood of condom use (Kavanagh et al.,

2013; Rubin et al., 2013). In addition, clinicians reported decreased likelihood to recommend

and concerns about provision of LARCs for clients with behaviors that are more common in

adolescence than in later years, including: not in a monogamous relationship, history of STI, and

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

14

nulliparous. It is important to note that these studies straddle a period of time when

recommendations about adolescents and LARCs were just beginning to be disseminated and all

of these studies occurred before the American Academy of Pediatrics published their policy

statement about adolescents and LARCs.

Five of the studies surveyed providers who had reason to be better informed about

LARCs than many practicing primary care providers due to their roles. The participants in the

Biggs et al. study (2014) and the Vaaler et al. (2012) studies were clinicians and medical

directors at family planning clinics. The study participants in the Kohn et al. (2012) study were

SBHC clinicians attending a reproductive health initiative. The study participants in the Madden

et al. (2010) study were obstetricians-gynecologists, and the participants in the Kavanaugh et al.

(2013) study were family planning clinic staff members. Clinicians working in settings such as

family planning, womens health, and obstetrics and gynecology have greater knowledge levels

about LARCs than their counterparts working in primary care (Harper et al., 2014).

Clinicians across the studies demonstrated an apparent lack of knowledge regarding

contraindications for LARCs. In the Kohn et al., (2012) study this was explicitly

measured with a knowledge assessment. In the other studies, the lack of

knowledge was inferred from reported likelihood to prescribe and attitudes

towards recommending LARCs. This analysis is complicated by the fact that

these surveys and interviews were evaluating provider attitudes and

likelihood of recommendation rather than direct knowledge, and it is possible

that attitudes and likelihood of recommendation have influences aside from

knowledge of contraindications (e.g. a provider may know that an IUD is not

contraindicated for an adolescent with a history of Chlamydia four months

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

15

ago, but may still choose not to recommend due to personal beliefs).

Despite the difficulty in analyzing knowledge directly across the studies,

there was enough commonality of provider attitudes and beliefs across

studies to make reasonable inferences about deficits in knowledge or at least

specific areas where clinicians may benefit from increased information about

LARCs, especially as many of the misconceptions are characteristics more

common in adolescents and young women than in older women.

Clinicians in five of the studies (Biggs et al., 2014, Harper et al., 2013,

Kavanaugh et al., 2013; Madden et al., 2010; Rubin et al., 2013) reported negative attitudes or

unwillingness to recommend LARCs for nulliparous women. Clinicians in three studies

(Kavanagh et al., 2013; Madden et al., 2010; Rubin et al., 2013) had negative attitudes or were

unlikely to recommend LARCs to women not in monogamous relationships. Clinicians in five

studies also reported negative attitudes or unwillingness to recommend LARCs for women with

either a recent history of STI or remote history of PID (Biggs et al., 2014;Harper et al, 2013;

Kohn et al., 2012; Madden et al., 2010; Vaaler et al., 2012). None of these characteristics

are considered to be contraindications for any LARCs.

The research question that prompted this systematic review is partially answered through

the literature. While clinicians generally view LARCs as safe, many clinicians have overly

restrictive views of eligibility for LARCs that disproportionately affect adolescents. There are

remaining gaps in the literature that should be addressed to better define intervention efforts to

improve provider knowledge of LARCs and ultimately increase adolescent use of LARCs.

Strengths and Limitations

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

16

Weaknesses of the review include the varying methodology of the studies. Researchers

used different survey instruments, although many of the questions were similar in concept.

Many of the studies were assessing practices surrounding LARCs generally (not specific to

adolescents) and findings regarding adolescents were identified during analysis and not as a

primary focus.

Importantly, many of the studies focused on IUD attitudes and practices. Although IUDs

are the most commonly used LARC, the study that considered IUDs separately from the

hormonal contraceptive implant showed higher acceptance and knowledge of the hormonal

contraceptive implant (Biggs et al., 2014). In addition, the knowledge deficits surrounding the

hormonal contraceptive implant were different than those about IUDs in both the Biggs et al.

study as well as the Vaaler et al. (2012) study, suggesting that the methods might need to be

evaluated separately.

Another important weakness is the failure to identify variance in practice across clinician

types. One study only considered nurse practitioner attitudes and practices and found overall

rates of LARC misconceptions and prescribing practices roughly similar to averages across other

studies (Harper et al., 2013). Other studies involved physicians only (Madden et al., 2011; Rubin

et al., 2013) or involved physicians and non-physician clinicians but other than in demographic

tables, did not differentiate data in attitudes and practices across clinician types or grouped all

non-physician clinicians together. In addition, many of the studies that included non-physician

clinicians had over-representation of physicians, perhaps due to sampling methods such as

sampling medical directors (Biggs et al., 2014).

This review has several strengths. The review considers both quantitative and qualitative

studies, which is significant as one of the areas of interest is attitudes, which may be difficult to

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

17

appreciate through quantitative analysis alone. Despite varying methodologies, clear themes and

patterns have emerged from the review. There are specific areas of knowledge about LARCs,

particularly IUDs, that clinicians are widely deficient in and which can be used to guide future

research and potential interventions.

Future Research

Future research about clinician attitudes to the provision of LARCs to adolescents should

be focused exclusively on adolescents. While it is important to consider provider attitudes and

knowledge level about LARCs across all ages of women, in-depth analysis of the specific

attitudes and practices of providers towards adolescents could lead to more specific interventions

to address the needs of providers caring for adolescent women. Future research should also

ideally seek to define whether or not there are differences in clinician type in LARC attitudes and

practice. Many studies treated clinicians as a homogenous group, but with variable training and

potentially different counseling styles, more attention should be paid to whether or not difference

exists in attitudes and practices.

Research about IUDs was heavily represented in this review. Hormonal contraceptive

implants were not well represented in the studies and two of the studies demonstrated that the

knowledge gaps surrounding the implant are different than those surrounding the IUD (Biggs et

al., 2014; Vaaler et al., 2012). More research is necessary to define the specific knowledge

deficits surrounding implants and to help determine clinician needs.

Some of the studies included non-clinicians in analysis of attitudes and practices

surrounding LARCs (Kavanaugh et al., 2013; Kohn et al., 2012). This is an area of research that

may merit separate development. The inclusion of non-clinicians in these studies made some of

the information difficult to evaluate and compare but the results of the non-clinician surveys and

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

18

interviews provide some interesting information about beliefs about LARCs. Non-clinicians,

especially those in roles such as health educator, may influence client choice about contraceptive

method and their beliefs about the methods and specific knowledge gaps should be identified.

Implications for Clinical Practice

This review provides important information for all clinicians participating in adolescent

care. Current clinical practice in teen contraception is discordant with evidence-based practice.

Clinician-directed interventions are necessary which address both the identified knowledge gaps

and increase clinician efficacy in counseling for LARCs. The research provides direction on the

nature of educational interventions required as well as who would most benefit from

interventions. Studies have demonstrated that clinicians working in primary care have lower

knowledge levels and decreased frequency of recommending LARCs (Harper et al., 2013). This

suggests that although all clinicians might potentially benefit from interventions aimed to

increase knowledge level and efficacy in counseling for LARCs, family practice clinicians may

have the greatest need.

Robertson and Jochelson (2006) conducted a systematic review of the literature on

behavior change interventions directed toward clinicians and found that education was necessary

in a behavior change intervention but was not sufficient to produce behavior change. Clinicians

have a demonstrated need for education about LARCs but in order for that education to have an

impact, it must be paired with other intervention strategies that support clinicians. A cliniciandirected intervention focused on improving knowledge about LARCs and increasing efficacy in

counseling adolescents about LARCs would necessarily address the identified knowledge gaps

and misconceptions, particularly contraindications and adverse effects, but would also provide

the practical support necessary to increase the likelihood of success in the clinical environment.

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

19

Adolescents require support in overcoming access barriers as well as financial barriers.

Clinicians working with adolescents would also benefit from having patient education materials

targeted to their population. Multiple studies reviewed showed higher knowledge scores and

likelihood of recommending LARCs in clinicians working in clinics where LARCs were

available on site and did not require referral (Biggs et al.,2014; Harper et al., 2013; Kohn et al.,

2012; Vaaler et al., 2012). In addition, in a study not included in this systematic review, having

ever trained in LARC insertion was highly correlated with likeliness to recommend, even in

clinicians working in clinic where LARCs were not available on-site (Greenberg et al., 2013).

Training providers for LARC insertion and providing support for ongoing competency would

also increase the effectiveness of a clinician intervention. A doctoral prepared nurse is uniquely

suited to the requirements of developing a clinician-focused intervention strategy using the

information gleaned in this systematic review as well as research regarding best practice in

clinician intervention strategies coupled with behavior change theory. A well-researched

intervention strategy has the potential to enhance provider knowledge and efficacy in the

provision of LARCs as well as ultimately impact adolescent pregnancy rates.

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

20

References

American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. (2014, January). NP Fact Sheet.

Retrieved from http://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2014). Policy statement: Contraception for

adolescents. Pediatrics, 134, 1244-1256, doi: 10.1542/peds.2014.2299

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2012). ACOG

committee opinion- Adolescents and long-acting reversible

contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Washington, D.C.:

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, retrieved from

http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions

Biggs, M.A., Harper, C.C., Malvin, J., & Brandis, C.D. (2014). Factors

influencing the provision of long-acting reversible contraception in

California. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 123(3), 593-602, doi:

10.1097/AOG.0000000000000137

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). U.S. medical eligibility criteria for

contraceptive use, 2010: Adapted from the World Health Organization Medical Eligibility

Criteria for contraceptive use, 4th edition. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report

Recommendations and Reports, 59(rr04), 1-6, retrieved from:

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5904a1.htm?s_cid=rr5904a1_e

Finer, LB, & Zolna, MR. (2011). Unintended pregnancy in the United States:

Incidence and disparities. Contraception, 84(5), 478-485, doi:

10.10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

21

Fuller, J. (2007). Adolescents and contraception: The nurses role as

counselor. Nursing for Womens Health, 11(6), 546-556, retrieved from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18088292

Greenberg, K.B., Makino, K.K., & Coles, M.J. (2013). Factors associated with

provision of long acting reversible contraception among adolescent

health care providers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(3), 372-374,

doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.003

Guttmacher Institute. (2013, December). Unintended Pregnancy in the

United States. Retrieved from : http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/FBUnintended-Pregnancy-US.html

Guttmacher Institute. (2014, June). Contraceptive Use in the United States.

Retrieved from : http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contr_use.html

Harper, C.C., Stratton, L., Raine, T.R., Thompson, K., Henderson, J.T., Blum,

M., Postlethwaite, D., & Speidel, J.J. (2013). Counseling and provision

of long-acting reversible contraception in the US: National survey of

nurse practitioners. Preventive Medicine, 57(6), 883-888,

doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.005

Hubacher, D. (2002). The checkered history and bright future of intrauterine contraception in the

United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34(2), 98-103, retrieved

from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3409802.html

Kavanaugh, M., Frohwirth, L., Jerman, J., Popkin, R., & Ethier, K. (2013). Longacting reversible contraception for adolescents and young adults:

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

22

Patient and provider perspectives. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent

Gynecology. 26(2), doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.10.006

Kohn, J.E., Hacker, J.G., Rousselle, M.A., & Gold, M. (2012). Knowledge of and

likelihood to recommend intrauterine devices for adolescents among

school based health center providers. Journal of Adolescent Health,

51(4), 319-324, doi: 10.1016/j.j.adohealth.2011.12.024

Madden, T., Allsworth, J.E., Hladky, K.J., Secura, G.M. & Peipert, J.F. (2011).

Intrauterine contraception in Saint Louis: A survey of obstetriciangynecologists knowledge and attitudes. Contraception, 81(2), 112116, doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.08.002

Paladino, H., Blenning, C., & Judkins, D.Z. (2006). What are contraindications to IUDs? Journal

of Family Practice, 55(8), 726-729, retrieved from: http://www.jfponline.com/index.php?

id=22143&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=171650

Robertson, R. & Jochelson, K. (2006). Interventions that change clinician behavior: Mapping

the literature. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 1-37, retrieved from:

http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/interventions-change-clinicianbehaviour-mapping-literature

Rubin, S., Davis, K., & McKee, M.D. (2013). New York City physicians views of providing

long-acting reversible contraception to adolescents. Annals of Family Medicine, 11(2),

130-136, doi: 10.1370/afm.1450

Sheeder, J., Tocce, K., Stevens-Simon, C. (2008). Reasons for ineffective

contraceptive use antedating pregnancies part 1: An indicator of gaps

ADOLESCENT CONTRACEPTION

23

in family planning. Maternal Child Health Journal, 13(3), 295-305, doi:

10.1007/s10995-008-0360-2

Tyler, C.P., Whiteman, M.K., Zapata, L.B., Curtis, K.M., Hillis, S.D., &

Marchbanks, P.A. (2012). Health care provider attitudes and practices

related to intrauterine devices for nulliparous women. Obstetrics and

Gynecology, 119(4), 762-771, doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824aca39

United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of

Adolescent Health. (2014, August 22). Choosing an Evidence-Based

Program and Curriculum. Retrieved from:

http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/oahinitiatives/teen_pregnancy/training/curriculum.html

Vaaler, M., Kalanges, L., Fonseca, V., & Castrucci, B. (2012). Urban-rural differences in

attitudes and practices toward long-acting reversible contraceptives among family

planning providers in Texas. Womens Health Issues, 22(2), 157-162, doi:

10.1016/jwhj.2011.11.004

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Contraception for the Medically Challenging PatientD'EverandContraception for the Medically Challenging PatientRebecca H. AllenPas encore d'évaluation

- Hunt-Gibbon SUM 2019Document34 pagesHunt-Gibbon SUM 2019fatimaPas encore d'évaluation

- Finalpaper HealthchangeDocument8 pagesFinalpaper Healthchangeapi-500609372Pas encore d'évaluation

- DP 203Document63 pagesDP 203charu parasherPas encore d'évaluation

- Primary and Secondary Infertility NotesDocument17 pagesPrimary and Secondary Infertility NotesMeangafo GraciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Polysubstance Abuse - Final PaperDocument10 pagesPolysubstance Abuse - Final Paperapi-695907422Pas encore d'évaluation

- ReportDocument13 pagesReportapi-663410827Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research Final DraftDocument15 pagesResearch Final Draftapi-736869233Pas encore d'évaluation

- ResearchDocument15 pagesResearchapi-736973985Pas encore d'évaluation

- ReportDocument13 pagesReportapi-663135887Pas encore d'évaluation

- Improving The Implementation of Evidence Based Clinical P - 2015 - Journal of AdDocument8 pagesImproving The Implementation of Evidence Based Clinical P - 2015 - Journal of AdVahlufi Eka putriPas encore d'évaluation

- Factors Influencing Contraceptive Uptake Among Lactating Mothers (6-24 Months) - A Case Study of 2medical Reception Station (2MRS)Document7 pagesFactors Influencing Contraceptive Uptake Among Lactating Mothers (6-24 Months) - A Case Study of 2medical Reception Station (2MRS)NanaKarikariMintahPas encore d'évaluation

- Knowledge Behavior Attitude of Teenage Pregnant Women On Reproductive HealthDocument67 pagesKnowledge Behavior Attitude of Teenage Pregnant Women On Reproductive HealthJacklyn PaciblePas encore d'évaluation

- Health Belief ModelDocument12 pagesHealth Belief Modelrenzelpacleb123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 6 (Maternal)Document61 pagesChapter 6 (Maternal)Veloria AbegailPas encore d'évaluation

- Ignorance Is Not Bliss: The Case For Comprehensive Reproductive Counseling For Women With Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument14 pagesIgnorance Is Not Bliss: The Case For Comprehensive Reproductive Counseling For Women With Chronic Kidney DiseaseAnnette ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- Predicting Adherence To Antiretroviral Therapy Among Pregnant Women in Guyana: Utility of The Health Belief ModelDocument10 pagesPredicting Adherence To Antiretroviral Therapy Among Pregnant Women in Guyana: Utility of The Health Belief ModelRiska Resty WasitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Overview of Infertility - UpToDateDocument16 pagesOverview of Infertility - UpToDateTaís CidrãoPas encore d'évaluation

- Research PaperDocument12 pagesResearch Paperapi-350307316Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bessem GloryDocument18 pagesBessem Gloryayafor eric pekwalekePas encore d'évaluation

- ContraceptionDocument3 pagesContraceptionsheaton7Pas encore d'évaluation

- archivev3i3MDIwMTMxMjQ3 PDFDocument7 pagesarchivev3i3MDIwMTMxMjQ3 PDFLatasha WilderPas encore d'évaluation

- 14 KnowledgeofContraceptivesMethodsandAppraisalofHealthEducationamongMarriedWoman PDFDocument14 pages14 KnowledgeofContraceptivesMethodsandAppraisalofHealthEducationamongMarriedWoman PDFArdin MunrekPas encore d'évaluation

- Ethical Concerns Relating To Taking Birth Control PillsDocument8 pagesEthical Concerns Relating To Taking Birth Control PillsMichael MbithiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ational Ublic Ealth Ction Lan: N P H A PDocument26 pagesAtional Ublic Ealth Ction Lan: N P H A PAbhay RanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Contraception 2012 08 012Document22 pagesContraception 2012 08 012AjiPatriajatiPas encore d'évaluation

- 2019 Article 729Document18 pages2019 Article 729api-625120170Pas encore d'évaluation

- Women Empowerment, Men's Attitude and Modern Contraceptives Use in PakistanDocument18 pagesWomen Empowerment, Men's Attitude and Modern Contraceptives Use in PakistanBhavita KumariPas encore d'évaluation

- Concept Paper 1 RegiemaeDocument14 pagesConcept Paper 1 Regiemaecuesta.renelynPas encore d'évaluation

- Camp Testimony 2011-01-12Document6 pagesCamp Testimony 2011-01-12rosiePas encore d'évaluation

- Months After Licensure Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Practices: A Survey of US Physicians 18Document11 pagesMonths After Licensure Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Practices: A Survey of US Physicians 18api-30279712Pas encore d'évaluation

- Anticipating PGDDocument10 pagesAnticipating PGDArlin Chyntia DewiPas encore d'évaluation

- Review MEC 2016Document7 pagesReview MEC 2016Leydi Laura QuirozPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidence-Based Practice in HealthcareDocument9 pagesEvidence-Based Practice in Healthcareselina_kollsPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing ResearchDocument12 pagesNursing Researchapi-735684768Pas encore d'évaluation

- Psychological Evaluations For Assisted Reproductive Intervention: Guidelines For Clinical PracticeDocument8 pagesPsychological Evaluations For Assisted Reproductive Intervention: Guidelines For Clinical PracticeandreaPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Behaviors of Primigravida TeenagersDocument6 pagesHealth Behaviors of Primigravida TeenagersAubrey UniquePas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 - Alomari Et AlDocument18 pages2017 - Alomari Et AlazeemathmariyamPas encore d'évaluation

- Providing Contraception ToDocument15 pagesProviding Contraception ToJEFFERSON MUÑOZPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Research PaperDocument11 pagesNursing Research Paperapi-719825532Pas encore d'évaluation

- Acog Committee Opinion: Adolescents and Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Implants and Intrauterine DevicesDocument10 pagesAcog Committee Opinion: Adolescents and Long-Acting Reversible Contraception: Implants and Intrauterine DevicesLuis Eduardo Olarte CharryPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing Research PaperDocument17 pagesNursing Research PaperZacob Anthony100% (1)

- Adolescent Demand For Contraception and Family Planning Services in Low-And Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic ReviewDocument20 pagesAdolescent Demand For Contraception and Family Planning Services in Low-And Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic ReviewMusie KurabachewPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Chapters 1 3Document19 pagesResearch Chapters 1 3mothballs2003Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ruiz, Patricia Ruiz, Shaneikah ScopeandStandardDocument5 pagesRuiz, Patricia Ruiz, Shaneikah ScopeandStandardPatricia Dianne RuizPas encore d'évaluation

- FactorsthatinfluencemotherstobreastfeedDocument18 pagesFactorsthatinfluencemotherstobreastfeedapi-353823437Pas encore d'évaluation

- Since DirectDocument1 pageSince Directnanik setyawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Call To Action For Contraceptive SafetyDocument16 pagesCall To Action For Contraceptive SafetyPopulation & Development Program (PopDev)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Research ReferencesDocument47 pagesResearch ReferencesVaishali SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexis Fiorello Phase Three Ethics Part TwoDocument7 pagesAlexis Fiorello Phase Three Ethics Part TwoElite TutorsPas encore d'évaluation

- Comms485-Final Capstone Report CompressedDocument132 pagesComms485-Final Capstone Report Compressedapi-298348208Pas encore d'évaluation

- Path Analysis On Factors Affecting The Choice of Female Surgical Contraceptive Method in Kendal, Central JavaDocument12 pagesPath Analysis On Factors Affecting The Choice of Female Surgical Contraceptive Method in Kendal, Central Javaanon_44859125Pas encore d'évaluation

- Unplanned Pregnancy and Its Associated FactorsDocument11 pagesUnplanned Pregnancy and Its Associated Factorskenny. hyphensPas encore d'évaluation

- ComparisonofcnmvsmdcareDocument9 pagesComparisonofcnmvsmdcarePandora HardtmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Paper ESSAYDocument5 pagesSample Paper ESSAYWycliffePas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal ReproDocument6 pagesJurnal ReproSiti AliyahPas encore d'évaluation

- XhducncDocument10 pagesXhducncBiaggi NugrahaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Research Paper Birth ControlDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Birth Controllinudyt0lov2100% (1)

- Topics For MCNDocument5 pagesTopics For MCNHulyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Disrupting The Pathways of Social Determinants ofDocument10 pagesDisrupting The Pathways of Social Determinants ofIGA ABRAHAMPas encore d'évaluation

- CDSMP PresentationDocument16 pagesCDSMP Presentationapi-314835119Pas encore d'évaluation

- Running Head: SBHC Policy Analysis 1Document17 pagesRunning Head: SBHC Policy Analysis 1api-314835119Pas encore d'évaluation

- Soles Competency DNPDocument5 pagesSoles Competency DNPapi-314835119Pas encore d'évaluation

- DNP Reflection-SolesDocument5 pagesDNP Reflection-Solesapi-314835119Pas encore d'évaluation

- New Estrogen and ProgesteroneDocument39 pagesNew Estrogen and ProgesteroneWegrimel AriegaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Beautiful Brute Eden ONeillDocument268 pagesBeautiful Brute Eden ONeillZULYVASQUEZVIVAS100% (1)

- Pills & Copper TDocument30 pagesPills & Copper TMamata ManandharPas encore d'évaluation

- Seminar On National Health and Family Welfare Programmes Related To Maternal and ChildhealthDocument21 pagesSeminar On National Health and Family Welfare Programmes Related To Maternal and ChildhealthKondapavuluru Jyothi81% (36)

- Medical TerminologyDocument10 pagesMedical TerminologyColumbus MedicinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Fibroids (Uterine Myomas) - ClinicalKeyDocument25 pagesFibroids (Uterine Myomas) - ClinicalKeyfebri febiPas encore d'évaluation

- Character List An American TragedyDocument2 pagesCharacter List An American TragedyЗдравка ПарушеваPas encore d'évaluation

- Fertility and Infertility: The Purpose of Reproduction Students' WorksheetDocument9 pagesFertility and Infertility: The Purpose of Reproduction Students' WorksheetCristian RajagukgukPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary Chart of U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria For Contraceptive UseDocument2 pagesSummary Chart of U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria For Contraceptive UseBlessy AbrahamPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit Title: Female Reproduction Title of The Lessons: Female Reproductive System Duration: 6 HrsDocument57 pagesUnit Title: Female Reproduction Title of The Lessons: Female Reproductive System Duration: 6 HrsShaira UntalanPas encore d'évaluation

- Menopause Remedy Folliculinum Differential DiagnosisDocument13 pagesMenopause Remedy Folliculinum Differential Diagnosismapati66100% (2)

- 2018 Article 12thEuropeanHeadacheFederationDocument147 pages2018 Article 12thEuropeanHeadacheFederationNurul NadzriPas encore d'évaluation

- Gynecology & Obstetrics: Khaled Khalilia ImleDocument30 pagesGynecology & Obstetrics: Khaled Khalilia ImleuyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Poster Presentation Final 30 11 06Document1 pagePoster Presentation Final 30 11 06RasanjaleePas encore d'évaluation

- Case 2: Gumalo, Glethel Heruela, Michelle Jalandoni, IreenaDocument44 pagesCase 2: Gumalo, Glethel Heruela, Michelle Jalandoni, IreenaMichelle TheresePas encore d'évaluation

- New Estrogen and ProgesteroneDocument56 pagesNew Estrogen and ProgesteroneHBrPas encore d'évaluation

- Unpacking The Self: Lesson I: The Physical and The Sexual SelfDocument6 pagesUnpacking The Self: Lesson I: The Physical and The Sexual SelfElma Jane L. MitantePas encore d'évaluation

- Family Planning - 1Document8 pagesFamily Planning - 1Khibul LimPas encore d'évaluation

- Imbong v. Ochoa, G.R. No. 204819, 721 SCRA 146, Apr. 8, 2014.Document2 pagesImbong v. Ochoa, G.R. No. 204819, 721 SCRA 146, Apr. 8, 2014.Ching TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Multiple ChoiceDocument55 pagesMultiple Choicetri ebtaPas encore d'évaluation

- "In The Shadow of Beaumont Tower: An Anthology" by T. A. SilvestriDocument283 pages"In The Shadow of Beaumont Tower: An Anthology" by T. A. SilvestriTylerSilvestriPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy 102 Practice Exam #3Document13 pagesAnatomy 102 Practice Exam #3lhayes123467% (6)

- CiplaMed - Contraception Cafeteria - 2019-06-21Document12 pagesCiplaMed - Contraception Cafeteria - 2019-06-21Ayushman UjjawalPas encore d'évaluation

- Andrew Na TicsDocument4 pagesAndrew Na TicsLouigene Tinao DonatoPas encore d'évaluation

- Barrier Contraceptive Method (Autosaved)Document12 pagesBarrier Contraceptive Method (Autosaved)Okera JamesPas encore d'évaluation

- RizalDocument16 pagesRizalJet Besacruz0% (2)

- Birth Control: Search For.Document4 pagesBirth Control: Search For.sujingthetPas encore d'évaluation

- Anatomy and Physiology of Female Reproductive SystemDocument12 pagesAnatomy and Physiology of Female Reproductive SystemSyed Isamil100% (1)

- Contraceptives 1-5compiled PDFDocument67 pagesContraceptives 1-5compiled PDFMyranda Zahrah PutriPas encore d'évaluation

- Maternal and Child Nursing Answers and RationaleDocument94 pagesMaternal and Child Nursing Answers and RationaleAnn Michelle Tarrobago100% (1)