Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Sara West - Nysca Submission

Transféré par

api-320564931Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Sara West - Nysca Submission

Transféré par

api-320564931Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

Public Relations and Crisis Communication:

The Effects of Terrorism Crises on SMEs and Consumer Discretionary Spending

Sara E. West

Pace University

Author Note

Sara E. West, Department of Media, Communications, and Visual Arts, Pace University.

Sara E. West is a graduate student in the MCVA Department at Pace University.

This research was done under the supervision of Dr. Paul Ziek of Pace University.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Sara West, contact email:

sw51090p@pace.edu.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

Abstract

It has been theorized by Choi et al., that peoples materialistic consumption behaviors can be

influenced by social events (Choi et al., 2007, p. 1), so this researcher conducted several

experiments in order to evaluate and analyze how the current consumer public retaliates during

times of terror, and how those reactions affect small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs). Four

terrorist attacks from the last five years were investigated and assessed using two experimental

designs. With the help of Qualtrics Survey Software, public opinion in regards to terrorism and

consumer discretionary spending were gathered through an anonymous 18-question survey.

Additionally, over 100,000 publicly published Tweets were evaluated for situational-relevant

material pertaining to the four attacks. The results showed that consumers were empathetic

towards earlier attacks (in 2012 and in 2013), however, as time went on and violence and attacks

became more prevalent, the consumer public become more apathetic, possibly due to adaptation

and unconscious coping strategies (Tur-Sinai, 2013, p. 2 257). It is important to understand past

attacks in order to better grasp future trends and market policy and public relation (PR) strategy

before they are set into motion.

Keywords: consumer discretionary spending, crises, crisis communication, public relations (PR),

small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs), terrorist attacks

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

Public Relations and Crisis Communication:

The Effects of Terrorism Crises on SMEs and Consumer Discretionary Spending

Terrorist attacks directly affect the ability of commercial businesses to: create, connect,

advertise, distribute, and ultimately profit from products or services. Therefore it is often

assumed that, terrorist activity unfavorably affects the willingness of the consuming public to

trust, engage, and buy from distributors, especially from foreign markets. However, the

American public has used several past terrorist attacks as chances to boost local SMEs profits

and the communitys economy.

Literature Review

From January 1, 2010 through December 31, 2015, the United States endured 44

terrorist-related crises (Johnston, 2016). As specified by the United States Federal Bureau of

Investigation (FBI), terrorism is defined as an intended act of violence that appears to frighten, or

negatively pressure the general public or government, by mass destruction, assassination, or

kidnapping (FBI, n.d.). A common misconception in regards to terrorist attacks is that in order

for one to be considered a domestic attack, the perpetrators must be American citizens.

However, the FBI considers any terrorist attack, occur[ing] primarily within the territorial

jurisdiction of the U.S. a domestic attack (FBI, n.d.). Terrorist attacks affect all types of

business, especially SMEs, which are classified as ventures no more than 250 employees and

profit no more than $46 million in annual revenue (European Commission, 2016).

The greatest problem caused by terrorist attacks is that they breed crises. According to

Ziek (2015), for an incident to be categorized as a crisis, it needs to include the following

criteria: it must be a major, catastrophic event that gains media attention, which in turn

negatively affects both the short-term and long-term reputation of an organization (Ziek, 2015,

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

p. 37). However, how the organization reacts to crises can directly affect how the public

responds. Therefore, because no organization can escape their vulnerability, nor can they fully

prevent crisis, there is an importance to having a practical knowledge about crises management

(Ziek, 2015, p. 36).

Regardless of how many terrorist attacks there are, on both American and international

soil, there is one way that civilians can fight back: consumerism. Americans have the freedom to

consume by spending discretionary income. It is argued that consumerism is one of the factors

that saved American spirits after the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York City. Fashion

consumerism were key factors in the short-term economic and emotional recovery of the United

States after September 11 consum[ing] [is] the right and duty of freedom-loving civilized

people (Pham, 2011, p. 386). Because Americans thought of it as their responsibility to

preserve the American Dream, they kept spending to show the citizens of the world that the

perpetrators had no power over them, which characterize[s] the American way of life (Pham,

2011, p. 287). Former President George W. Bush has declared that terrorists hate our

freedoms (Bush, 2001), and chief among these freedoms is consumerist liberty (Pham, 2011,

p. 287). Bush even stated that the idea of the consumer culture is to have choices, the opposite

of being oppressed (Bush, 2001 via Pham, 2011, p. 391). Therefore, the ability to demonstrate

consumerism is essential to self-expression and to American freedom (Pham, 2011, p. 391).

Contrarily, in some ways this preservation of consumerism could be characterized as a

reflexive coping mechanism, coping after a crisis by examining the role that possessions play in

maintenance of self-identity (Pavia & Mason, 2014, p. 441). Specific individuals whom,

consumption and possession of products play an important role in life, satisfying enthusiasts

needs for uniqueness, mastery, and/or affiliation (Guiry et al., 2006, p. 75), control the

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

economic bounce-back, especially after a crisis. That is because this spending group has

discretionary income, which directly influences the business of SMEs. Discretionary income is

the earnings an individual has left after paying for life necessities (i.e. food, shelter, clothing, and

bills) (Nickolas, 2016). This monetary surplus has a substantial affect in boosting the countrys

economy because these are the dollars used to make non-essential luxury purchases. Due to the

fundamental properties of discretionary income, measuring how individuals spend this extra

money is one of the most straightforward ways to assess the health of an economy via Gross

Domestic Product (GDP) rating (Nickolas, 2016). Furthermore, it should be noted the significant

difference between the variety of market goods that are, and are not, affected during times of

terror. For example, capital goods [are] more strongly affected than consumption goods (TurSinai, 2013, p. 257). Capital goods, or durable goods, are the building blocks of the economy

because they are heavy-duty, long-lasting commodities that are necessary for the production of

other goods, (i.e. professional-grade tools and construction equipment) (Adkins, 2016). In

addition, durable goods are relatively unaffected by the occurrence of a temporary shock in the

economy (Tur-Sinai, 2013, p. 267), so a dip in market sales would not necessarily affect the

long-term creation or distribution of capital goods themselves (Adkins, 2016).

Whether rooted as a coping mechanism or an act of patriotism, peoples materialistic

consumption behaviors can be influenced by social events, (Choi et al., 2007, p. 1) and thus the

idea that: mortality salience effects materialistic consum[ers] (Choi et al., 2007, p. 1). An

adaptation pattern that relies on dependency of terror is created, in regards to non-durable goods

[versus] durable goods (Tur-Sinai, 2013, p. 257). Therefore, [the] public internalize[s] the

realization that if it wishes to sustain a reasonable standard of living it must maintain consumer

behaviors and patterns before, during, and after terrorist events (Tur-Sinai, 2013, p. 267).

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

Creating a direct correlation between discretionary consumer spending habits and terrorism

crises, specifically in relation to SMEs.

Methodology

For analytical purposes, a mixed-method strategy was used to survey consumers with

discretionary income, and to probe four domestic terrorist attacks on American soil from the last

five years via Twitter. The researcher chose a mixed-method because together the two methods

would provide stronger background information and evidence in regards to consumer

discretionary spending habits, and thus lend a more powerful argument.

A survey was used in order to collect quantitative data that would give breadth and depth

to the study. Quantitative research is important because it assigns physical quantities to each

parameter being tested (Treadwell, 2014, p.14). For this survey, Qualtrics Survey Software was

used to allocate and collect answers from a convenient, non-probable (and therefore nonrandom) sample cohort. The universe was comprised of individuals who primarily fit into the

classification of, consumer. From there, the universe was broken down to create a population

composed of, consumers with discretionary income. After that, the established population was

further fragmented into a sample cohort made up of 50 individuals, whom identified as:

consumers with discretionary income who successfully completed the survey, Consumerism

During Terrorism.

Consumerism During Terrorism was an 18-question survey (West, 2016 p.1-18), which

approximately took three-to-five minutes to complete (for native-English speakers). The survey

was accessible for a five-day period starting at 04:14 PM Eastern Standard Time (EST) on

Friday, February 19, 2016, until 12:21 PM EST on Wednesday, February 24, 2016. All survey

participants were informed of the nature and purpose of the survey through a written statement

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

that accompanied a clickable link (which was compatible with most Internet or Wi-Fi-capable

devices) (see Appendix A). The interactive link was sent out via personal text messages, through

iMessages (specific to Apple products), and individually in Facebook Messenger messages

(specific to Facebook Messenger). In addition, the link was available through the creators

personal Facebook page via a status update and as a part of a clickable link on the creators

personal Instagram account (accessible through the Instagram phone application or website).

The 18-questions were oriented around the NOIR method which stands for four basic

levels of measurement: nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio (Treadwell, 2014, p. 79). There

were nine nominal questions, which allowed the participant to label or attach meaning to the

answer choices (see Appendix B). Four of the questions were ordinal, which allowed for items

to be ranked in preferential order (see Appendix C). One of the 18 questions was an interval

question, which gave insight about overall statistics (see Appendix D). And lastly, there were

four ratio-based questions, to provide more sophisticated statistical information (Treadwell,

2014, p. 79) (see Appendix E). The first six questions were broader, with the intention of

warming up the participants in hopes that they would be more inclined to give more honest and

accurate answers later on in the survey when questions became more personal. For the

remaining two-thirds of the survey, questions were funneled into being increasingly more

explicit in detail- especially those queries concerning personal income and discretionary

spending habits.

Qualitative data provides in-depth knowledge (Treadwell, 2014, p. 193), and was

collected and analyzed via Twitter. This social media platform was specifically chosen as the

basis for research because of the unavoidable parameters the application itself puts on those who

interact with it. Tweets are only allowed to be a maximum of 140-characters in length (including

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

spaces). Posts can be made through any Internet- or Wi-Fi-capable device directly through

Twitters website or on the free, downloadable, phone (or desktop) application.

The samples used for the qualitative study were composed of four universal groups which

included anyone who had every made a Tweet about a terrorist attack. However, this universe

was far too massive of a group to work with, so each universe was further broken down into a

specific sample that met the following criteria: people who published a publicly-accessible

Tweet, with at least one character of text, and included a situational-specific hashtag. The four

aggressions examined were: the Aurora Theater Shooting (Friday, July 20, 2012), the Boston

Marathon Bombing (Monday, April 15, 2013), the Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood

Shooting (Friday, November 27, 2015), and the San Bernardino Incident (Wednesday, December

2, 2015).

Statistical boundaries were set and tangible manifest data was collected. This data

included the total number of Tweets with crisis-specific hashtags that were published during the

30-day period following the attacks. The crisis-specific hashtags that were considered for this

assessment were according to the trending hashtag at the time of the event. For the Aurora

Theater Shooting, it was #AuroraShooting; for the Boston Marathon Bombing,

#BostonMarathon; for the Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood Shooting, #StandWithPP; and

for the San Bernardino Incident, #SanBernardino. The Tweets were then scrutinized according

to occurrence frequency and systematically recorded. It was necessary to assign worth to the

data, so an analytical framework was put into motion in which six basic words (and their

conjugated variations) were examined and allocated a value. The words of interest included:

thoughts/think, prayers, help, shop, charity, and give (see Appendix F, Appendix G, Appendix H,

and Appendix I).

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

Because this study was also concerned with the effects on SME market trends, it was also

important to look at overall habitual spending progression, specifically in regards to consumer

discretionary spending on non-durable goods. Using data sets and charts made available by The

United States Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis, the researcher was able

to see the average amount of billions of dollars in personal discretionary spending in regards to

non-durable goods for the month prior to each terrorist crises as well as the month following (see

Appendix J, Appendix K, Appendix L, and Appendix M).

Results

Answers collected from the survey varied in degree of usefulness. However, after going

over the results in detail, several things became apparent in terms of shopping preferences,

discretionary spending trends, and consumer habits. For example, participants were asked what

they spent the majority of their discretionary income on. Eleven choices were provided which

covered 11 fields of consumer interest (see Appendix N). Overwhelmingly, the majority of

people chose the third option: eating out at a restaurant (e.g. not cooking at home). This was

significant, because contrary to what the research had assumed, it proved that the general public

would rather put their dollars towards purchases that provide instant gratification, like enjoying a

meal at a restaurant, versus buying a lasting tangible product.

Another discovery was the seemingly lackadaisical response to possibly the most

important question on the survey. Question six explicitly asked respondents to rate on a scale

from one-to-five (one being the least and five being the most), how much global terrorism

worries you (see Appendix O). The majority of those surveyed indicated that they were more

neutral in regards to how much worry they dedicated towards the thought of global terrorism.

The average response, 3.11, was just barely over the midline of 3.0. This median illustrates

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

10

almost complete neutrality in regards to whether or not the average American consumer worries

about global terrorism. Furthermore, because it is assumed that the sample cohort appropriately

represents the current U.S. population, this finding is perhaps the most impactful. This detached

response demonstrates a startling trend in terms of a national attitude adjustment, if you will, that

has not only recognized terrorist crises as inevitable, but perhaps even accepted the state of crises

as the new standard of normal. As argued by Tur-Sinai (as cited in Kirschenbaum, 2006, p. 133):

The longer the terror continue[s], the more the public accepts the possibility that [they]

will be in this situation for the long term; therefore, deviation from ordinary consumer

behavior steadily declines after each terror incident (Tur-Sinai, 2013, p. 257).

Behavioral adaptations minimize the ongoing crises, reflecting an admission that crisis is now a

part of daily life and society (Tur-Sinai, 2013, p. 258).

Discussion

Breaking down Twitter verbiage provided functionally applicable information that was

directly relatable to the content analysis of the consumer spending data sets. After the Aurora

Theater Shooting in July 2012 and the Boston Marathon Bombing the following year,

discretionary spending actually jumped higher the month following each attach. Hence, there

was an increase in discretionary spending. Additionally, after both the Aurora Theater Shooting

and the Boston Marathon Bombing, there was an increase in Tweets related to shopping locally

(see Appendix P). Also, many companies gave back to the recently attacked community through

charitable fundraisers and giving back percentages of each purchase to those in need (see

Appendix P).

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

11

However, it seemed as if by 2015, Americans had grown weary of terrorist attacks. After

both the Planned Parenthood Shooting and the San Bernardino Incident of 2015, the following

months there was actually a drop in total consumer discretionary expenditures (see Appendix L

and Appendix M). Although there was still some unanimity among those who Tweeted in

regards to the Planned Parenthood Shooting, it was more of a movement of consensus to do as

the hashtag suggests, and stand with Planned Parenthood (see Appendix Q). There was also an

overall decrease in the amount of Tweets for both the Planned Parenthood Shooting and the San

Bernardino Incident, in comparable proportion to the amount of Tweets published after the

Aurora Theater Shooting and the Boston Marathon Bombing.

SMEs are vital to the U.S. economy because they comprise more than 50% of all

domestic business (Suominen, 2014). Because many SMEs are local businesses, they are

directly affected by local commerce trends, grassroots PR campaigns, and how the community

rallies together. Ergo, the fact that the communities banded together, specifically after the

Aurora Theater Shooting (2012) and the Boston Marathon Bombing (2013), illustrates that

communal Tweeting can directly affect SME revenue. That trend is further supported by the

increase in discretionary spending that was seen in the national consumer reports (see Appendix

J and Appendix K).

We cannot predict when terrorist attacks are going to occur. Therefore, these findings are

particularly important because they can propose how SMEs should act after a terrorist crisis. By

holding charitable sales and events, not only does the business drum up foot traffic for them, but

also the organization is able to illustrate a more humanitarian side. Similarly, the organizations

choice of message strategy affects both how people perceive the crises and the image of the

organization (Stephens et al., 2005, p. 391). In other words, consumers will remember which

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

12

companies offered an olive branch during tough times, and in addition, will show loyalty to those

who give back to the neighborhood.

In order to have a well-rounded study, it is critical that the facilitator be cognizant of the

inevitable problems of reliability and validity, as well as the studys limitations. One specific

limitation was that at least four survey participants referenced home as not in the U.S., but

instead in Western Europe. Because this study is specifically concerned with terrorism crises

in the U.S., the information gathered from Western Europeans may have skewed reliability and

validity. Not only may these individuals differ in consumer attitudes and beliefs, but also the

structural integrity and economics of SMEs in Western Europe slightly differ to those in the

United States. Another limitation with the survey was the lack of concrete definitions. For

example, the word terrorism was never clarified for the survey candidate. If the definition had

not previously been established, a persons frame of reference would affect how the question and

answers were interpreted. Similarly, several questions used vague measures to assess specific

feelings. Phrases such as least enjoyable versus most enjoyable and varying degrees of

how likely one is to do something, can be easily misinterpreted.

Limitations related to the validity of the Twitter content analysis have to do with the

availability of Tweets through private and public functions that are allowed to each person and

their profiles settings. Because Twitter is a social media platform, it allows each user to choose

whether published Tweets can be seen by everyone (publicly) or just by people who follow the

Tweeter (privately). Consequently, that means there is an undisclosed number of Tweets that the

researcher was not able to access because of privacy settings.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

13

Conclusion

At some point the consuming population will adopt a survival strategy, in order to

minimize the expected impact of a terror incident (Tur-Sinai, 2013, p. 257). In just a relatively

short five-year span of time, it is already been illustrated that consumers are getting fed up with

the persistent assaults. Tweeting decreased following each event, sales no longer rose in the

following months, and an apathetic tone is took reign. Almost as if Americans are indicating,

that terror [has] become part of daily life (Tur-Sinai, 2013, p. 258).

Terrorism is inescapable; and every terrorist attack is going to rattle fiscal commerce and

heighten consumer concern, to an extent. Therefore, it has become increasingly important for

PR practitioners to understand market trends set into motion by these attacks. As someone who

is interested in working in the PR field for the SME marketplace, it is absolutely necessary that I

be able to create and maintain survival strategies and adaptations, especially during and

following times of crises.

By gaining an understanding of the general consumers attitude about terrorist activity, I

will learn to anticipate different retail environment trends as companies and consumers acclimate

to the unfolding events.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

14

References

Adkins, W.D. (2016). What is the difference between durable goods and non-durable goods?

Retrieved from http://smallbusiness.chron.com/difference-between-durable-goodsnondurable-goods-34928.html

Becker, G.S. & Rubinstein, Y. (2004). Fear and the response to terrorism: an economic analysis.

Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/cjd/bse_cjd.htm

Bush, G.W. Joint session of Congress and the Nation. (2001, September 20). President Bush

addresses the Nation Washington, D.C. Retrieved from

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpsrv/nation/specials/attacked/transcripts/bushaddress_092001.html

Chamie, B.C. & Ikeda, A.A. (2015). The Value for the consumer in retail. Brazilian Business

Review, Victria, 12, 2, 3, 46-65. Retrieved from

http://search.proquest.com/pqrl/docview/1721582377/CDCC8DAA61F744BDPQ/2?acco

untid=13044

Choi, J., Kwon, K.N., & Lee, M. (2007). Understanding materialistic consumption: a terror

management perspective. Journal of Research for Consumers, 13, 1-4. Retrieved from

http://search.proquest.com/docview/216590140?accountid=13044

European Commission. (2016, February 26). What is an SME? Retrieved from

http://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/business-friendly-environment/smedefinition/index_en.htm

Guiry, M., Mgi, A.W., & Lutz, R.J. (2006). Defining and measuring recreational shopper

identity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34, 74-83. doi:

10.1177/009207030528242

Johnston, W.R. (2016, February 16). Terrorist attacks and related incidents in the United

States. Johnston archives [Data file]. Retrieved from

http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/terrorism/wrjp255a.html

Kang, M. & Johnson, K.K.P. (2011). Retail therapy: scale development. Clothing & Textiles

Research Journal, 29 (1), 3-19. doi: 10.1177/0887302X113399424

Nickolas, S. (2016). What is the difference between disposable income and discretionary

income? Retrieved from http://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/033015/whatdifference-between-disposable-income-and-discretionary-income.asp

Pavia, T.M & Mason, M.J. (2014). The reflexive relationship between consumer behavior and

adaptive coping. Journal of Consumer Research, Inc., 441-454. doi: 10.1086/422121

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

15

Pham, M.T. (2011). The right to fashion in the age of terrorism. Signs: Journal of Women in

Culture and Society, 36, 385-410. doi: 0097-9740/2011/3602-00011

Stephens, K.K., Malone, P.C., & Bailey, C.M. (2005). Communicating with stakeholders during

a crisis. Journal of Business Communication, 42, 4, 390-419. doi:

10.1177/0021943605279057

Suominen, K. (2014, February 5). State of SME finance in the United States 2014: Year of new

providers. Retrieved from https://katisuominen.wordpress.com/2014/02/05/187/

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). (n.d.). Terrorism: definitions of terrorism in the U.S.

Code. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/investigate/terrorism/terrorismdefinition

The United States Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis. (n.d.). National

income and product accounts tables [Data files]. Retrieved from

http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=9&step=1&acrdn=2#reqid=9&step=1&isur

i=1&903=82

Treadwell, D. (2014). Introducing Communication Research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA:

SAGE Publications, Inc.

Tur-Sinai, A. (September 2013). Adaptation patterns and consumer behavior as a dependency

on terror. Mind and Society, 13, 257-269. doi:10.1007/s11299-014-0154-8

West, S.E. (February 2016). Consumerism during terrorism [Online survey]. Retrieved from

https://pace.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_6VTn8p3tvElJcNL

Ziek, P. (2015, March 1). Crisis vs. controversy. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis

Management, 23, 36-41. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.12073

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

16

Appendix A

Pre-Survey Consent Statement

The following is a screenshot from the survey distributors personal Facebook page. The

intention of the survey was clearly state in a three-sentence declaration, which was to be read

prior to participation.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

17

Appendix B

Nominal Question Example

Below is a screenshot from one of the nine nominal questions that were asked in the survey,

Consumerism During Terrorism.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

18

Appendix C

Ordinal Question Example

Below is a screenshot from one of the four ordinal questions that were asked in the survey,

Consumerism During Terrorism.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

19

Appendix D

Interval Question Example

Below is a screenshot from the interval question that was asked in the survey, Consumerism

During Terrorism.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

20

Appendix E

Ratio-Based Question Example

Below is a screenshot from one of the four ratio-based questions that were asked in the survey,

Consumerism During Terrorism.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

21

Appendix F

Aurora Theater Shooting Qualitative Research and Twitter Verbiage Breakdown

Thirty days following the July 20, 2012 Aurora Theater Shooting, over 12,000 Tweets were

published with the relevant hashtag, #AuroraShooting. The following is the qualitative research

gathered in regards to the Aurora Theater Shooting, as well as the specific Twitter verbiage

breakdown of those Tweets.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

22

Appendix G

Boston Marathon Bombing Qualitative Research and Twitter Verbiage Breakdown

After the Boston Marathon Bombing on April 15, 2013, Twitter was inundated with personal

opinions and news reports. During the 30-days immediately following the attack, over 64,000

Tweets that included the hashtag, #BostonMarathon, were publicly published. The following is

the qualitative research gathered in regards to the event, as well as the specific Twitter verbiage

breakdown of those Tweets.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

23

Appendix H

Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood Shooting Research and Twitter Verbiage Breakdown

On November 27, 2015, Robert Lewis Dear Jr. carried out a shooting in Colorado Springs,

Colorado. For the next 30 days, there were over 20,000 Tweets with the situational-relevant

hashtag, #StandWithPP. The following is the qualitative research gathered in regards to the

event, as well as the specific Twitter verbiage breakdown of those Tweets.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

24

Appendix I

San Bernardino Incident Research and Twitter Verbiage Breakdown

Over 13,000 Tweets were publicly published with the hashtag, #SanBernardino, over the 30 days

immediately following the San Bernardino attacks on December 2, 2015. The following is a

screenshot of the qualitative research gathered in regards to the San Bernardino Incident, as well

as the specific Twitter verbiage breakdown of those Tweets.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

25

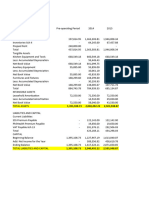

Appendix J

The Monthly Personal Consumption Spending Chart of 2012

The monthly breakdown of consumer discretionary spending habits on non-durable goods in the

United States during 2012.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

26

Appendix K

The Monthly Personal Consumption Spending Chart of 2013

The monthly breakdown of consumer discretionary spending habits on non-durable goods in the

United States during 2013.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

27

Appendix L

The Monthly Personal Consumption Spending Chart of 2015

The monthly breakdown of consumer discretionary spending habits on non-durable goods in the

United States during 2015.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

28

Appendix M

The Monthly Personal Consumption Spending Chart of 2016

The monthly breakdown of consumer discretionary spending habits on non-durable goods in the

United States during 2016.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

29

Appendix N

Data Reduction of Survey Question Nine

Below illustrates the response variation according to the 50-person cohort sample that completed

the survey, Consumerism During Terrorism.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

30

Appendix O

Data Reduction of Survey Question Six

Below illustrates the response variation according to the 50-person cohort sample that completed

the survey, Consumerism During Terrorism.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

31

Appendix P

Boston Marathon Tweets

The following collection of screenshots were collected after the Boston Marathon Bombing and

illustrate the consumer and producer rallying that took place.

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

32

Running head: PUBLIC RELATIONS AND CRISIS COMMUNICATION

33

Appendix Q

Collection of Tweets that Incorporated #StandWithPP

The following collection of Tweets that were positive and called for fraternity of mutual

supporters of Planned Parenthood.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- List of SAP Status CodesDocument19 pagesList of SAP Status Codesmajid D71% (7)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Grant Proposal PromptDocument17 pagesGrant Proposal Promptapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- 19.lewin, David. Human Resources Management in The 21st CenturyDocument12 pages19.lewin, David. Human Resources Management in The 21st CenturymiudorinaPas encore d'évaluation

- FINA 385 Theory of Finance I Tutorials CAPMDocument17 pagesFINA 385 Theory of Finance I Tutorials CAPMgradesaverPas encore d'évaluation

- Aesthetics PaperDocument7 pagesAesthetics Paperapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final PaperDocument24 pagesFinal Paperapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- PROMPT: Be Sure To Read Over Chapter 7 On Group Communication andDocument2 pagesPROMPT: Be Sure To Read Over Chapter 7 On Group Communication andapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Analytical ReportDocument13 pagesAnalytical Reportapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Press Release Psa PromptDocument2 pagesPress Release Psa Promptapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cover Letter Resume PromptDocument3 pagesCover Letter Resume Promptapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Email and Cultural Memo PromptDocument2 pagesEmail and Cultural Memo Promptapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ad Agency FinalDocument22 pagesAd Agency Finalapi-320564931Pas encore d'évaluation

- QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesQuestionnaireDivya BajajPas encore d'évaluation

- TRDocument18 pagesTRharshal49Pas encore d'évaluation

- RAD Project PlanDocument9 pagesRAD Project PlannasoonyPas encore d'évaluation

- TOA Reviewer (UE) - Bank Reconcilation PDFDocument1 pageTOA Reviewer (UE) - Bank Reconcilation PDFjhallylipmaPas encore d'évaluation

- MBA Result 2014 16Document7 pagesMBA Result 2014 16SanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Na SW Atio Witch Onal HB (NP Lpa Bang PSB Aym Gla B) Men Des NT SHDocument37 pagesNa SW Atio Witch Onal HB (NP Lpa Bang PSB Aym Gla B) Men Des NT SHArafatPas encore d'évaluation

- Sr. No. Name of Institution Address Board Line Fax No.: 1 Allahaba D BankDocument9 pagesSr. No. Name of Institution Address Board Line Fax No.: 1 Allahaba D Banksaurs2Pas encore d'évaluation

- CommoditiesDocument122 pagesCommoditiesAnil TiwariPas encore d'évaluation

- Share Holders Right To Participate in The Management of The CompanyDocument3 pagesShare Holders Right To Participate in The Management of The CompanyVishnu PathakPas encore d'évaluation

- Alliance Governance at Klarna: Managing and Controlling Risks of An Alliance PortfolioDocument9 pagesAlliance Governance at Klarna: Managing and Controlling Risks of An Alliance PortfolioAbhishek SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- MBA Course StructureDocument2 pagesMBA Course StructureAnupama JampaniPas encore d'évaluation

- 2189XXXXXXXXX316721 09 2019Document3 pages2189XXXXXXXXX316721 09 2019Sumit ChakrabortyPas encore d'évaluation

- Wordpress - The StoryDocument3 pagesWordpress - The Storydinucami62Pas encore d'évaluation

- Online Shopping and Its ImpactDocument33 pagesOnline Shopping and Its ImpactAkhil MohananPas encore d'évaluation

- Limba EnglezaDocument9 pagesLimba EnglezamamatadeusernamePas encore d'évaluation

- Issue 7: October 1998Document68 pagesIssue 7: October 1998Iin Mochamad SolihinPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Operation ManagementDocument78 pagesIntroduction To Operation ManagementNico Pascual IIIPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Format FSDocument2 pagesSample Format FStanglaolynettePas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Devices and Ehealth SolutionsDocument76 pagesMedical Devices and Ehealth SolutionsEliana Caceres TorricoPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 5Document31 pagesLesson 5Glenda DestrizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Debt Collector Disclosure StatementDocument8 pagesDebt Collector Disclosure StatementGreg WilderPas encore d'évaluation

- Ax2012 Enus Deviv 05 PDFDocument32 pagesAx2012 Enus Deviv 05 PDFBachtiar YanuariPas encore d'évaluation

- Distance Learning 2016 Telecom AcademyDocument17 pagesDistance Learning 2016 Telecom AcademyDyego FelixPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 Walters Global Salary SurveyDocument428 pages2017 Walters Global Salary SurveyDebbie CollettPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Case Study Between Two AirlineDocument56 pagesComparative Case Study Between Two AirlineGagandeep SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- BCG MatrixDocument1 pageBCG MatrixFritz IgnacioPas encore d'évaluation

- A Comparative Analysis On Fuel-Oil Distribution Companies of BangladeshDocument15 pagesA Comparative Analysis On Fuel-Oil Distribution Companies of BangladeshTanzir HasanPas encore d'évaluation