Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

You Ens November 1984

Transféré par

George William IrwinCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

You Ens November 1984

Transféré par

George William IrwinDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

EXCAVATING AN ALLEGORY:

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT LUNAIRE

Susan Youens

For

his song cycle Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21 of 1912,

Schoenberg selected twenty-one poems from the fifty rondels in Pierrot

Lunaire (1884) by the Belgian poet Albert Giraud, a collection translated

into German in 1891- 1892 by the poet and playwright Otto Erich Hartleben

(1864-1905).' Through his choice and arrangement of those twenty-one

poems, Sehoenberg carved from Giraud's collection of harlequinades the

tripartite tale of a creative artist's rebellion and frenzied "dereglement

des sens," the sterility and des pair that follow, and, finally, the journey

horne. The cycle ends in reconciliation with the past and recognition of a

new artistic order in which those elements of beauty and value from the

past, from tradition and one's cultural homeland, are incorporated.

Nach Bergamo, zur Heimat,

Kehrt nun Pierrot zurck,

Schwach dmmert schon im Osten

Der grne Horizont

--Der Mondstrahl ist das Ruder .

Fron/ispiece by Ado/phe Willelle, one oI /he Iounders oI/he Cha/ Noir in Mon/martre, JOT thejirst issue 0/ the arlts/ic journal Le Pierrot, Ire Annee. no. J, 6 Juillet

1888, with the coption, "La Parisienne: Pierrot blanc. Pierrot noir, je vous lais chevaliers du elair de Lune; allez. boycottez et amusez-moi'"

This allegory of a modern artist is present within Giraud's and Hartleben's Pierrot Lunaire, but scattered throughout the volume and obscured

from view by glimpses into other corners of Pierrot-Poet's often chaotic

inner world. Schoenberg recognized affinities between poems dispersed

throughout the work and rearranged them in order to clarify those relationships, heighten the effect of the recurring images, and trace more

clearly the steps of the Poet's progression from ecstasy to despair and

finally to peace and homecoming. To do so, he pruned away all the

poems from which either Pierrot or the moon is absent: the tale unfolds

by night, and the Moon is the embodiment of Poetry and Pierrot's alter

ego, the very souree of poetry at the beginning of Op. 21.

Schoenberg never, to my knowledge, explained or diseussed the rationale of his choice and ordering of the twenty-one poems in the cycle,

but it is easy to reeognize in Op. 21 a more meaningful order than the

96

SUSAN YOUENS

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT LUNA/RE

97

(deliberately?) jumbled series of fifty poems in the complete GiraudHartleben collection. There, the poet's mind leaps from one image, phantasm, fear, or caprice to another in the seemingly irrational fashion of

an unfettered imagination- behind the inscrutable mask of a clown is

unregulated whimsy. The pairs or even trios of successive poems linked

by a common image or theme always give way in Giraud's and Hartleben's

work 10 a disconcerting change of scene, a leap to another region of a

psychic landscape outside the dictates of Reason and the waking world.

Schoenberg imposed a coherent structure on those poems he chose and, in

so doing, excavated from the targer souree its principal "idea" cr "con-

cept," purifying it and liberating it from the unrelated images that cluster

about and hide it from view.

The "moonstruck Pierrot" of the title is the prototype of an artist,

including Giraud hirnself: in the last poem, "Cristal de Boheme," he writes

that he wears Pierrot's garb and is a Pierrot-" Je suis un Pierrot costume"

or, in Hartleben's translation, with its changed nuances, "Ich hab mich als

Pierrot verkleidet".' Pierrots were endemie everywhere in late nineteenth l

early twentieth century Europe as an archetype of the self-dramatizing

artist, who presents to the world a stylized mask both to symbolize and

veil artistic ferment, to distinguish the creative artist from the human being.

Behind the all-enveloping traditional costume of white blouse, white trousers, and floured face, the Pierrot-character changed with the passage of

time, from uncaring prankster to Romantic malheureux to Dandy, Decadent, and finally, into a brilliant, tormented figure submerged in a bizarre,

airless inner world. The Pierrots of the 1880's had already, before Giraud's

Pierrot Lunaire, assumed a sadistic and sinister guise, so to find hirn

thieving and torturing was nothing new, but here, he is in turn tortured

and killed, the prey of self-exacerbated agonies of the mind and imagination. In his heightened self-consciousness, he is a Janus-faced creature:

the poseur, the "je m'en moque" of extravagant gestures compounded

equally of elegance and violence, calculated for their effect upon others,

gives way on occasion to the death-haunted introvert who, all alone,

trembles at the phantasmagorical and multiple deaths conjured by an overwrought fancy.

Giraud's Pierrot evolved from the zannis, or comic clown-servant figures from Bergamo who were part of the panoply of stock characters in the

commedia deli 'arte. Pierrot's most distant ancestor was Pulcinella, a

character created in Naples who, chameleon-like,

played many roles' and

,

who had a knack for parody, pranks, and playing the imposter. The French

Pierrot became a distinct figure, differentiated from the Italian Pulcinella

or Pedrolino, during the early days of the commedia dell'arte in France

during the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Pierrot and another

A sketch 01 Albert Giraud (born Albert Kayenbergh in Louvain, 1860-1929) Irom

Camille Hantet, Les Ecrivains Belges Contemporains de langue fran~aise 1800-1946,

val. 1 (Liege: H. Dessain, 1946), p. /45. Giraud initially hoped 10 become a concer!

pianist.

Photograph 0/ Quo Erich Hart/eben fram the jrontispiece 10 Otto Erich Hartleben .

Briefe an Freunde. vo/. 2, ed. by Franz Ferdinand Heilmue/ler (Eer/in: S. Fische;

Verlag, 1912).

98

$USAN YOUENS

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT LUNA /RE

99

of the zannis- Harlequin- developed into more fixed and easily identifiable personalities in France, the central characters in such late seventeenthcentury plays as "Arlequin Empereur de la Lune" by a certain Monsieur

Anne de Fatouville (died ca. 17(0), performed several times between 1684

and 1719. Watteau's famous Comediens Italiens (1719-1720?), now in the

National Gallery in Washington, D.C., is among the earliest transfigurations of Pierrot into the melancholy artist-prototype:' here, as in Arlequin,

Pierrot et Scapin of 1716, and, most strikingly, in Oilles (another name

far the French Pierrot), Pierrot is the central figure, clearly separate from

the remainder of the troupe. (It is in part this detachment, this aloofness

from the quotidian life around hirn, that appealed so strongly to nineteenthcentury France). In Oilles, he is larger-than-life, larger than the other

comedians dustered in back of his feet and legs, who seem to leer and

gossip and peer in other directions while he looks straight ahead. Tbe fullfrontal pose is expressive of a self-sufficient, lonely pride and of vulnerability, the latter quality heightened by the hands hanging limply at his

sides. The unblinking gaze, resigned and withdrawn, seems to see through

and beyond the viewer, ' and yet, the passivity has a certain air of confrontation as well.

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, in their essay on Watteau, later published in L 'Art au dix-huilieme siecle, made of the eighteenth-century

master the precursor " ... of the modern artist in the fine, the disinterested

sense, the modern artist in pursuit of an ideal, despising money, careless

of the morrow, leading a hazardous ... a bohemian . .. existence" 7 whose

ill health, melancholy, and, eventually, misanthropy left their imprint on

his work, for all the beauty of the amber light that plays about his fingers.

The commedia dell'arte players of Watteau's canvases become, accarding

to Romantic legend, "lyrical personages, " no longer real. This cf course is

Watteau through nineteenth century eyes that saw in the paintings "a world

beyond" and in the artist hirnself a Romantic befare his time, an inaccurate

conception and thoroughly tainted by the biographical fallacy but powerful

and long-lived: Giraud begins his Pierrot Lunaire by dreaming of a " ...

theatre de chambre/Dont Breughel peindrait les volets (the Breughel of

Dulle Griet, surely?),/ Shakespeare, les pales palais, lEt Watteau, les fonds

couleur d'ambre".

Gille, by Antoine Watteau (1684- 1721), in the Louvre, one 01 the painter's last

works. Same art hislorians, including Donald Posner in Antoine Watteau (London:

Weidenjeld & Nicolson. 1984), p. 270. conjecture that /he painting was intended os

a shopsign Jor the actar Bel/on;, who opened a cole after his retirement Irom the

foires.

Other Pierrot-incarnations after the eighteenth-century playactors in

Watteau's sunlit canvases went into the making of Giraud's moonstruck

poet, induding the "nouveau Pierrot" created by the famous Parisian

pantomime artist Jean-Gaspard, called Baptiste, Deburau (1796-1846) at

the Thetre des Funambules, the Deburau subsequently of Jean-Louis

Barrault in "Les Enfants du Paradis.'" Deburau changed the traditional

costume, leaving off the frilled white ruff and donning instead a black skull-

SUSAN YOUENS

'00

eap, and, more important, altered the familiar eharaeterizations of the

prankish buffoon or the melaneholy and lovesiek suitor by adding elements

of perversion, of macabre and violent actions committed by an insouciant,

jaded, detaehed, ironie ereature, no longer naive. Baudelaire wrote of

hirn in his study "De l'Essenee du rire et generalement du eomique dans

les arts plastiques" as a mysterious creature, "pale as the IDoon ... supple

and mute as a serpent. "9 Giraud, who wrote three essays on Baudelaire's

poetry published in the Jeune Revue Litteraire in 1881," would surely have

known both Baudelaire's essay and Deburau. Certainly Baudelaire's influenee is evident in mueh of Giraud's poetry: the spleen, grotesquerie, allegories of the Poet and the World, the fascination with death and vice, entire

borrowed phrases and images, have their souree in Les F1eurs du mal.

Deburau's Pierrot quickly found its way into written theatre, both

lighthearted farees such as "Pierrot Posthume: Arlequinade en un aete

et en vers" by Theophile Gautier (1811-1872), first performed at the

Theatre du Vaudeville on Oetober 4, 1847, and, later, the bizarre mimeeomedies of the Belle Epoque. Despite the suggestively maeabre title,

Gautier's play is an amusing pasquinade, but there are hints of the later

moondrunk ereature: in a monologue in scene iv, Pierrot speaks of Colombine's disquiet when she discovers his true nature after their marriage"Elle s'inquietait de mes ehants la lune, / De mes moyens de vivre et de

chereher fortune." Almost forty years before Giraud's Pierrot Lunaire, the

down has a1ready become a nocturnal prowler. Later, the Parisian artist and

earicaturist Adolphe Willette (1857- 1926)" made of Pierrot an even more

sophisticated deseendant of the earlier dandies-Giraud refers to Willette

in the thirty-eighth poem of Pierrot Lunaire, "Brosseur de lune": "Un

tres pale rayon de lune/Sur le dos de son habit noir,iPierrot-Willette sort

1e soir /Pour aller en bonne fortune" (Hartleben omits the topieal-nationa1istie referenee in his translation). Theodore de Banville (1823-1891) also

sang the newly-transformed Pierrot's praise in his poem" Au Pierrot de

Willette," written in 1884, the same year that Pierrot Lunaire appeared:

Cher Pierrot, qui d'un clin d'oeil

Me mentre tout ce qui m'aime,

J'aime ta joie, et ton dueil

Meme!

Taime ton regard de feu,

Ta bravoure et ton coeur mle,

Bien que tu sembles un peu

Ple. L2

In 1888, Willette founded a short-lived weekly artistie and satirieal journal in Paris ealled Le Pierrot (the last issue appeared on 20 March 1891).

In his pen-and-ink drawings of the motto figure, he alternated between

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT LUNA/RE

'0'

a "Pierrot blane" dressed in the traditional white-smoeked eostume and

a "Pierrot nair," who combines the white Tuff, floury make-up, skulleap, and slippers of older Pierrots with blaek evening dress, half Parisian

sophisticate and half eommedia down. For the frontispieee of the first

issue on 6 July 1888, both the "Pierrot blane" and Willette's "Pierrot

noir" are dubbed "chevaliers du Clair de Lune" by a bare-breasted

woman, her scepter ornamented with acrescent moon, who seems a

debased, cafe-concert descendant of Delacroix's Liberty Leading the

People. The journal is filled with poetry, farces, miniature dramas about

the commedia characters, induding works in which Giraud's influence

is apparent ... "La Ballade des Pierrots Morts" by Maurice Guillemot,

a moonlight poem in three dizains and an Invoi (sie) begins with apolar

scene,

Sur les fonds blemis du ciel boreal.

Les nuits de Noel, quand la lune est claire,

Les Pierrots dHunts, fils de l'Ideal.

Montent des tombeaux au pays polaire. I'

reminiscent of the ninth poem, "Pierrot Polaire," in Pierrot Lunaire.

Pierrots like Giraud's wreak havoc in other late nineteenth century

works as weil. Joris-Karl Huysmans eollaborated with the writer Leon

Hennique and an artist named Jules Cheret on a drama, part pantomime

action, part written dialogue, entitled "Pierrot sceptique," printed in

1881, in which Pierrot is utterly unaffected by the death of his wife and

runs off with the "femme de carton" Therese when his tailor's skeleton

is discovered in his doset." Willette in Le Pierrot illustrated an advertisement for a pantomime, Paul Margueritte's "Pierrot assassin de sa

fernrne" in which Sarah Bernhardt played the leading role in 1883 at

the Trocadero. But the dosest kin to Giraud's Pierrot lunaire is Verlaine's

mad, phosphorescent specter of a "Pierrot" (1868, published in 1882),

a figure unlike the better-known Pierrot of "Pantomime" in Fetes galantes (1869). There, he is a gaily irreverent glutton and nonchalant jester

whose pranks lighten the overall gentle melancholy of the volume, but in

the lesser-known sonnet, he is a death's-head figure, his blouse a windingsheet, a personification of the inmost terrors of the death-obsessed soul.

Avec le bruit d'un vol d'oiseaux de nuit qui passe,

Ses manches blanches font vaguement par l'espace

Des signes fous auxquels personne ne repond.

Ses yeux sont deux grands trous ou rampe du phosphore

Et la farine rend plus effroyable encore

Sa face exsangue aux nez pointu de moribond. 1 S

Giraud's Pierrot is less horrifie of countenance, but his mad gestures

and violent actions fill fifty poems, not one. The hallucinatory mayhem

102

SUSAN YOUENS

is gentled, however, rendered in pastels by a poet seemingly incapable

of a forcefulness of expression to match the content and images of his

poetry.

Pierrot Lunaire was the first of three Pierrot works by the Belgian

poet and literary critic Jean Heurtaut, born in Louvain on 23 June 1860

and died in Brussels on 26 December 1929. The second was "Pierrot

Narcisse" (1887), averse play in alexandrines which Giraud described on

the title page as a "songe d'hiver, comedie fiabesque," and the third and

last, published in 1898, was Heros et Pierrots." In "Pierrot Narcisse,"

the clown, long an egocentric narcissist, falls in love with his own reflection in the mirror, recalling the forty-seventh poem of Pierrot Lunaire,

"Le miroir." There, Pierrot looks in the mirror and laughs to see his

reflection crowned, "coiffe," by the crescent moon. In the rhyming dedication to uPierrot Narcisse/' Giraud writes that Pierrot, a creature "sans

profession," would be his lifelong shadow:

Voici bien trcis ans et demi

Que j'ai rirne "Pierrot Lunaire."

Je suis eneore ton ami:

e'est vraiment extraordinaire.

e'est pourquoi, - puisque e'est mon sort,

Captif de la rime et du nombre,

D'avoir Pierrot jusqu'a la mort

A cte du mai, comme une ombre ...

HeurtautiGiraud's memoirs, published the year he died in 1929, are

entitled Les souvenirs d'un autre-contemplation not only of another and

younger self, but a fabled alter ego whose artistic tribulations and escapades

could be separated from its creator in much the same fashion as Schumann's troupe of F1orestan, Eusebius, and Magister Raro. Pierrot removes

his mask to reveal Albert Giraud who in turn strips off his mask to reveal

a shadowy figure named Heurtaut about whom we know very little.

We do know, from Giraud's own testimony, that Pierrot Lunaire is

the poetic record of his rebellion against and return to those Parnassian

ideals which he had earlier condemned:

Petits rapsodes impeccables, ennemies de la passion et I'eloquence, cherehant

I'absolue beaute dans la ligne et dans la couleur, pipeurs de rirnes et de metres.

impersonnels par necessite, originaux par imitation, gonfIes d'erudition,

pedante, indechiffrables comme des sphinx. 17

Only a few years after writing this tirade, Giraud was hirnself concerned

with line and meter, the imitation of past masters and forms-fifty rondels

in a row-, and ingenious rhymes. His first volume as a penitent Parnassian

returned to the fold is divided between a smaller number of pastel or beautifully jewelled landscapes, purely Iyrical evocations- the great purpie and

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT LUNA/RE

103

gold birds of "Decor," the clouds like celestial fish with fins of gold,

pearl, and ivory in "Les Nuages," the fireflies sprinkled across the ladies'

gowns in the fete galante of "Souper sur I'eau"- and the gruesome,

macabre images that predominate. Pierrot drills hole in the screaming

Cassander's skulI, an executioner strides about with a dripping basket

full of decapitated heads, a tubercular moon oozes white blood, the sun

opens up its veins and red blood stains the sky, Pierrot quakes in terror

beneath a giant scimitar-horror piled upon horror in a crescendo throughout the volume, relieved only periodically by images of unalloyed beauty.

And yet, the power of these images is weakened, at times negated entirely

by Giraud's flat, paIlid, remote tone, an unemotionaI narrative manner,

dry and distanced that is often at variance with the subject. If the gap

between tone and content were ironic, the matter would be different, but

Giraud, unlike his much greater contemporary and Pierrot-puppeteer Jules

Laforgue, was no master of irony.

Hartleben utterly transforms Giraud's poetry for the better-immeasurably better. lt is a rare occurrence when a translation transcends its

source, when literature of less than the first rank is elevated to a considerably higher level through the intermediary of the translator , but

Pierrot lunaire in Hartleben's German is one of those rare instances. It is

as if Giraud's rondels were a draft in one language for Hartleben's "finished" work in another. Hartleben surpassed his own original works by far

with Pierrot lunaire-the erotic comedies, the charming but inconsequential

Iyric verse, the satires, and the single tragedy, famous in its day, are not

nearly its equal." He worked on the translations for six years, and, in a

letter to a friend and fellow writer Otto Julius Bierbaum, said that he

labored so hard on this task that many of the poems existed in three or

four different versions.

Freu mich sehr. dass Ihnen die Rondels so gut gefallen! Es sind aber auch in

der That wundervolle Sachen. Ich kann das sagen, weil sie wirklich nicht

von mir sind. Albert Giraud ist ein lebender Belgier. Seine Sachen sind bei

Lacombeez in Brussel erscheinen.

Allerdings-von diesen bersetzungen gehrt viel mir. Ich habe vielfach

berhaupt nicht "bersetzt," sondern nur ein Motiv aus dem franzsischen

Gedichte genommen und darber meins geschrieben . Ob das "erlaubt" ist oder

nicht, ist mir schnuppe, wenn nur was dabei herauskommt. Ich "arbeite" an

dieser Sammlung seit 1886, also sechs Jahre. Immer wieder bin ich mit zher

Liebe daran gegangen, manches ist drei-, viermal gedichtet. Ich hoffe also,

dass die Verse wirklich nicht den Eindruck von bersetzungen machen. 19

Significantly, Hartleben says of Giraud only, "Er ist ein lebender Belgier."

He abstains from any overt criticism of the poet, but the nature of his

translations- the fact that he often took only a motif or an image from the

104

SU$AN YOUENS

original and freely exercised his license to transform utterly the tone and

style-constitute an implicit negative judgment of Giraud.

With the exception of two brief poems from Heros et Pierrots, this

was Hartleben's last translation, and that is to be regretted. He was a

brilliant translator , far more gifted at that difficult metier than he was

either in original prose or poetry. Curiously, the distinctive mannerisms

and methods by which he transformed Giraud's poems are not to be found

so brilliantly employed in his own works. Giraud's poetry was certainly a

challenge: the Belgian poet's earlier criticisms of Parnassian poetry are

true of his own verse (the displacement of personal dissatisfactions onto

some other person or group of people is hardly uncommon). It is ironie

that poetry with so much blood and violence and pillage should be so

intrinsically bloodless, even when he is depicting a fantastic and horrifying

scene. The slimy, pulpy creatures that grip the poet's ship in the sea of

absinthe and sink it (number twenty-two, "Absinthe"), the vampire-like

and monstrous black butterflies in search of blood to drink (number nineteen, "PapilIons Noir") appear and disappear seemingly without a trace of

surprise, horror, cr strang emotion of any kind on Giraud's cr Pierrot's

part. Hartleben breaks up the even flow of Giraud's flat and preternaturally

calm recitation with fragmented phrases, exclamations, and questions,

much more vivid language expressive of stronger feelings . In order to do

so, he sometimes omits entirely one of Giraud's images and substitutes a

more colorful one of his own invention-in place of the slimy eddy or

backwash into which the poet's ship sinks in the last stanza of "Absinthe,"

Hartleben introduces a giant arm that suddenly appears from nowhere ...

attached to what or whom? ... and knocks the mast off the ship, sinking it:

Giraud

Mais soudain ma barque est etreinte

Par des poulpes visqueux et mous:

Au milieu d'un gluant remous

Je disparais, sans une plainte,

Dans une immense mer d 'absinthe.

Hartleben

Doch wehe! Was umklammert jah

Mein Schiff'?-Polypen, widrig, klebrig!

Ein Riesenarm zerknickt den MastUnd ohne Klagelaut versink ich

Im Ozeane des Absinths .

THE TEXT S OF PIERROT LUNA/RE

105

The change of verb tense from past and imperfect in Giraud to present

tense in Hartleben's translation, along with the breathless, agitated , telegraphie exclamations in the German, make the bizarre scene come alive.

Similarly, in the thirty-eighth poem, "Brosseur de lune," when Pierrot

first discovers the speck of moonlight on the back of his coat, Giraud

writes in his customary flat, narrative tone, "Mais sa toilette l'importune."

which Hartleben in "Der Mondfleck" translates as "Pltzlich- strt ihn

was an seinem Anzug ... ". Later in the same poem, when Giraud in a

matter-of-fact way says, "11 s'imagine que c'est une /Tache de pltre .. . ",

Hartleben, typically for hirn, breaks the line up into jagged fragments .. .

" Warte! denkt er: das ist so ein Gipsfleck! I Wischt und wischt, dochbringt ihn nicht herunter!". Giraud's almost unvarying octosyllabic lines

become in Hartleben a variety of different poetic meters and line lengths,

ranging from the trochaic tetrameters and pentameters of " Rot und

Weiss ," with its masterly use of enjambement , beautifully unlike Giraud's

seemingly random use of the same gesture,

Ernst und schweigend streckt die Gebietenn

Nach Pierrot die geschmeidigen Hnde aus.

Langsam whlt sie die Finger ins lockige

Haar und presst sein fieberndes Haupt an

Kalte, feste starrende Brste.

to the brief, breathless lines of "Gebet an Pierrot " :

Pierrot! Mein Lachen

Hab ich verlernt!

Das Bild des Glanzes

Zerflosst - Zerfloss!

Hartleben often repeats key words or phrases in this emphatic and Expressionistic way, unlike Giraud, who seems to shy away from bold accentuation of any kind. The German translator also transforms Giraud's frequent

similes into metaphors or anthropomorphizing allegorical embodiments:

"the moon is a washerwoman" father than "camme une lavandiere."

With similes, the poet shows his hand, interposing an analogy that comes

from outside, rather than seeming to originate within the poem itself, and

therefore lessens the confrontational effect of the image.

Hartleben translated all fifty poems in Giraud's order, but Schoenberg

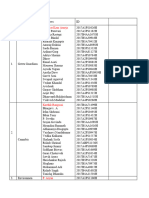

of course set only twenty-one, less than half. The following table shows

which works from the complete Pierrot Lunaire Schoenberg selected and

their placement in the song cycle.

106

SUSAN YOUENS

Hartleben 's translation

Schoenberg'sOp.21

1. Ein BOhne

2. Feerie

3. DerDandy

4. Schweres Loos

5. Eine blasse Wscherin

6. Serenade

3. Der Dandy

4. Eine blasse Wscherin

19. Serenade

7. Der Koch

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

Harlequinade

Nordpolfahrt

Colombine

Harlequin

Die Wolken

2. Colombine

13. Mein Bruder

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Raub

Herbst

Mondestrunken

Galgenlied

Selbstmord

Nacht

Sonnen-Ende

21. Der kranke Mond

22.

23.

24.

25.

Absinth

Kpfe!Kpfe!

Enthauptung

Rot und Weiss

26. VaIse de Chopin

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

Die Kirche

Madonna

Rote Messe

Die Kreuze

Gebet an Pierrot

Die Violine

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

Abend

Heimweh

0 alter Duft

Heimfahrt

Pantomime

Der Mondfleck

Das Alphabet

Das heilige Weiss

Morgen

Parodie

Moquerie

Die Laterne

Gemeinheit!

Landschaft

Im Spiegel

Souper

Die Estrade

Bhmischer Krystall

10. Raub

I. Mondestrunken

12. Galgenlied

8. Nacht

7. Der kranke Mond

13. Enthauptung

5. Valse de Chopin

6.

11.

14.

9.

Madonna

Rote Messe

Die Kreuze

Gebet an Pierrot

15. Heimweh

21. 0 alter Duft

20. Heimfahrt

18. Der Mondfleck

17. Parodie

16. Gemeinheit!

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT LUNAIRE

107

Sehoenberg ruthlessly pruned and re-arranged his chosen poems in order

to ereate three smalI, interrelated eydes from a non-eydic source. The fact

that Giraud's eolleetion has little apparent strueture or sehematic organization, beyond the existenee of an introduction and eondusion that frame

the fifty poems, is perhaps deliberate, the poetie eoneomitant of an interiar

world that contains all sorts of images and notions jumbled together. The

raw material from whieh poetry, erafted and fashioned and molded,

eventually emerges is not itself logical and ordered, but is instead marked

by the obsessive, disordered repetition of eertain themes and images and

by the diseontinuity eommon in mueh of twentieth eentury art.

Sehoenberg's purpose was different and required a different and

apparent strueture. In the first group of seven poems, Sehoenberg first

presents the poet revelling in the souree of poetry, or moonlight, rejecting

the past-symbolized by erystal-, then growing swiftly more disturbed,

his mind more and more diseased and disordered. In the seeond and eentral

eyde, night deseends, and terror, death, poetie martyrdom and sterility

dose in, and in the final eyde, he beeomes reeonciled with his past, with

poetie tradition, and returns horne.

I. 1. Mondestrunken

11. 8. Nacht

111. 15. Heimweh

2. Colombine

9. Gebet an Pierrot

3. Der Dandy

10. Raub

4. Eine blasse Wscherin

11 . Rote Messe

5. Valse de Chopin

6. Madonna

12. Galgenlied

13. Enthauptung

16. Gemeinheit !

17. Parodie

18. Der Mondfleck

19. Serenade

20. Heimfahrt

7. Der kranke Mond

14. Die Kreuze

21. 0 alter Duft

To create the three smaller eydes, he omitted those poems that were extraneous to his tale. The first two poems, "Eine Bhne" and "Feerie,"

have no mention of Pierrot, the moon, or poetry, and the referenees to

Breughel, Shakespeare, and Watteau in "Eine Bhne" would draw the

foeus away from the hallueinatory inner world, outward into the reader's

historical past. Furthermore, "Feerie" is a daylight poem, while Op. 21

is a work that begins by night, sinks into even blaeker and gloomier realms

in the eentral eyde, and only gradually emerges into the light of dawn in

the last two poems, "Heimfahrt" and "0 alter Duft." The other daylight

poems, such as "Morgen" (no. 41),

Ein rosig blasser. feiner Staub

Tanzt frh am Morgen auf den Grsern.

Leis klingt ein Singen, hell und klar,

Gleich fernem Himmelschor .

and "Feerie" are omitted. In "Morgen," the central figure is Cassander,

5USAN YUENS

108

the plump, boorish bourgeois, who pursues a sweet, young maiden through

the flowers in a beautiful daylit setting, with no mention of Pierrot.

Ein zartes. junges Dirnehen flieht

Scheu vor dem lsternen Cassander.

Die weissen Rckchen streifen leicht

Die Blumen-und es hebt sich duftend

Ein rosig blasser. feiner Staub.

The focus in the complete poems shifts away from the "moonstruck

Pierrot" rather frequently, but not so in the song cyde. Schoenberg thus

omits the three poems in which Harlequin is the central or the only figure:

number eight, "Harlequinade"; number eleven, "Harlequin"; and number

thirty-nine, "Das Alphabet," in which "lieutenant" Harlequin leads the

regiment of the vari-colored alphabet. The two beautifully Iyrical commedia

scenas, without a trace of grotesquerie or terror, are also omitted: number

forty-eight, "Souper," with its moonlit gondola for Pierrot and Colombine, who has fireflies in her hair and withered violets strewn at her feet,

and number thirty-seven, "Pantomime," in which Pierrot sings aserenade

from the bushes with the blue Italian sky shining overhead. Pierrot is simply

an element of the decor in these two static, if delightful, tableaux; he is not

the central figure.

If Pierrot or the moon or poetry are missing, the poem is not induded

in Op. 21. The fourth poem, "Schweres Laos," or "Deconvenue" in

Giraud, is certainly fanciful and grotesque- like a Breughel parable painting on gluttony, The Land oi Cockaigne perhaps, with its brutish louts

deprived of their roasts, tarts, and quince jellies, while insects with blue

wing-sheaths thump at the rose windows-, and the commedia characters

are there-a group of "Gilles" pull grimaces in the corner-, but Pierrot

is not, neither are the moon and poetry, so the poem is exduded from the

cyde. Other commedia figures, Cassander and Columbine, only appear

in Schoenberg's Op. 21 when they react to something Pierrot does: Cassander screaming in protest as Pierrot drills a hole in his head and smokes

Turkish tobacco through his human pipe. In "Gebet an Pierrot," someone

in mourning ("Schwarz weht die Flagge /Mir nun vom Mast") pleads with

Pierrot to restore light and laughter: one way to interpret the poem is to

infer that Pierrot, who wished to deflower Colombine in the tenth poem

(the second in Op . 21), has done so, and that she now pleads for an impossible return to innocence and joy, in one sense, to the commedia tradition in which she is courted and pursued but never won.

None of the landscape or nature poems lacking either Pierrot or the

moon are included, among them, number twelve, "Die Wolken" in which

the evening douds, with their tints of ivory, gold, and pearl, are captured

by the Night in nets; number thirty-three, "Abend," with its melancholy

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT LUNAIRE

109

white storks against a black background, the last rays of light shining from

a "hoffnungsleere Sonne"; and number forty-six, "Landschaft," in which

black birds cry out, a "cold, sad light" shines feebly through the grayish

atmosphere, and the sun, "yellow-red like a great egg," sinks. All three

poems have to do with sunset or the approach of night, three of five such

poems in Pierrot Lunaire. The others are number nineteen, "Nacht,"

which Schoenberg set and number twenty, "Sonnen-Ende," in which the

sun's blood flows out over the douds and the land, dyeing both red, as

an exhausted young voluptuary, an unknown, unnamed creature, also

dies. Similarly, in number fifteen, "Herbst," an unnamed and terrified

figure trembles in the midst of an autumn landscape of withered, brown

leaves .... Hartleben transformed Giraud's peculiarly French concept

of "spleen" (the title of the poem) into the peculiarly German "Angst."

Of the sunset poems, Schoenberg chose the most violent and bizarre,

"Nacht," with its swarm of giant, black butterflies that kill the sun's rays

and omits the four other sunset poems. "Nacht" furthermore has significant links with the end of Schoenberg's cyde: in "Nacht," a scent arises

from the depths, killing remembrance and accompanying the fall of utter

darkness,

Aus dem Qualm verlorner Tiefen

Steigt ein Duft, Errinrung mordend!

while in the last poem, a scent from olden times returns to bewitch the

0 alter Duft-aus Mrchenzeit,

senses:

Berauschest wieder meine Sinne!

Poetry, the moon, the poet: those crucial themes in Op. 21 are all

introduced in the first song of Schoenberg's cyde (the sixteenth poem of

Giraud's and Hartleben's complete volume).

Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt,

Giesst Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder,

Und eine Springflut berschwimmt

Den stillen Horizont.

Gelste, schauerlich und sss,

Durchschwimmen ohne Zahl die Fluten!

Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt,

Giesst Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder.

Der Dichter, den die Andacht treibt,

Berauscht sich an dem heilgen Tranke

Gen Himmel wendet er verzckt

Das Haupt und taumelnd saugt und schlrft er

Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt.

The moonlight is sacramental wine, an intoxicant that "the Poet" greedily

drinks "mit Augen." Wave after wave of moonlight floods "the still horizon" with numberless desires and emotions until Pierrot/Poet is drunk

SUSAN YUENS

110

and ecstatic. The moonlight is the source of poetry, filled with "Gelste"

that are both dreadful and sweet, and the poet steeps hirnself in that light

until he is dizzied and staggers to and fro, his senses reeling. The Rimbaudesque perception that a poet must experience all sorts of desires, to the

point of saturation, "dereglement" and beyond, leads to unexpected and

undesirable results, not the making of a poet but very nearly his undoing.

In every detail of "Mondestrunken, " there are links to other poems

that Schoenberg set in Op. 21, words, images, and themes: the wine is a

"holy drink" (Giraud speaks of "Ie poete religieuxlDe l'etrange absinthe

se soille ... ") and poetry a mystical, religious experience ... art as a

religion whose adherents at times imitate, parody or invert the rituals and

symbols of Catholicism and whose "holy figures" - Poetry and the Poetsuffer the martyrdom and death of Christ-figures . In the sixth poem,

"Madonna" (the twenty-eighth poem in Giraud/Hartleben), the poet begs

the "mother of all sorrows" (the moon?), with her bleeding breasts like two

red eyes- the poetic leitmotif of eyes again- , to mount the altar of his

verses and there hold the body of her son (the poet?) before mankind's

averted gaze, and in "Rote Messe," Pierrot celebrates a ghastly Communion by ripping the heart out of his breast and offering this new Host,

the sacramental chalice that contains poetry, at the altar. "Madonna" and

"Rote Messe" are paired in the complete Pierrot Lunaire, but separated

in the cycle: "Madonna" is in the first cyc1e, "Rote Messe" in the second.

"Madonna" is linked to the image of the gentle maiden from the heavens

("sanfte Magd des Himmels," an expression that evokes both the Moon

and the Virgin Mary), but the moon-madonna who earlier washed "cloths

woven from light" (poems formed from the source of poetry?) is now

wounded and cradles her dead son. With the second cycle, the moonlight

disappears, and Pierrot becomes poet-priest-martyr.

When a swarm of giant moths extinguish the sun in "Nacht," darkness falls. The entire central cycle is largely devoid of light,

Finstre, schwarze Riesenfalter

Tteten der Sonne Glanz.

("Nacht")

Das Bild des Glanzes

Zerfloss-Zerfloss!

("Gebet an Pierrot")

Durch die Finsterniss(" Raub")

Durch schmerzensdunkle Nacht . . .

("Enthauptung")

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT L UNA/RE

111

and the poems are shot through with references to the colors black and

red and to blood-no longer an analogy, as in "Valse de Chopin."

... schwarze Riesenfalter

("Nacht")

Schwarz weht die Flagge . ..

("Gebet an Pierrot")

Rote, frstliche Rubine

Blutge Tropfen alten Ruhmes . ..

(" Raub")

Auf einem schwarzen Seiden kissen . ..

(" Enthauptung")

Die triefend rote Hostie:

Sein Herz-in blutgen Fingern("Rote Messe")

Dran die Dichter stumm verbluten, .. .

Prunkend in des Blutes Scharlach! .. .

Eine rote Konigskrone.

("Die Kreuze")

The blood-red rubies in the tombs are "Iike eyes," recalling the Madonna's wounded breasts, "wie Augen, rot und offen"-in each, a bloodshot

accusatory stare mutely confronts the guilty plunderer and anarchist.

The earlier poem also foreshadows Pierro!'s and the poets' wounds

shortly after in the central section, when the blasphemer of religion

becomes hirnself a martyr. The blood and violence escalate in a terrifying

crescendo throughout the cycle, beginning with a monstrous nightfall

and Colombine's bitter prayer.

The thirteenth and fourteenth poems, "Enthauptung" (no. 24 in

the complete collection) and "Die Kreuze" (no. 39), exemplify Schoenberg's perception of close relationships between rondels separated in the

complete Giraud-Hartleben volume. The metaphor of poems as holy

crosses upon which mute, Christ-like poets bleed, their bodies pierced

by sword strokes and their heads crowned with the setting sun's bloodred glow, is preceded in Op. 21 by a poem in which Pierrot paces in terror

before an eerie, hallucinatory vision of a siekle moon, metamorphosed

into a Turkish scimitar on a black silk cushion. If the moon is the fons

et origo of poetry in Pierrot lunaire, then perhaps the scimitar represents

the immense power of incipient poetry-the exotie weapon rests, not

yet in use, on the black cushion of an otherwise unilluminated night

sky- , its death-dealing potential and the poe!'s terror at such a dread

realization. "Die Kreuze" is the consequence of "Enthauptung": the

SCSA:\ YOCE:\S

112

"schwelgten Schwerter" of "Die Kreuze" are multiples cf the single

Turkish seimitar of number rhirteen, and rhe feared deeapitarion in "Enthauptung" is followed by "Tot das Haupt" at the elose of the second

eycle. Mind and intellection (the head) are "dead," killed by rebellion

and the martyrdom that ensues.

When night falls ("Nacht"), a Pandora's Box of il1s descends vvith

the darkness, the host of evils analogous to the flood of "Gelste" in

the waves of moonlight at the beginning of the first cycle. Throughout

the second cyc1e, Pierrot is besieged by woes incurred in the first seven

poems: "Gebet an Pierrot," the second poem of the central segment, is

the response to the seeond poem of the first eycle, the consequences of

his desire in HColombine." In "Raub," he and his companions (the

eonternporaneous radical poets who have similarly swept tradition off

their dressing tables?) attempt to plunder the past of its jewels, tom

from their context, but without success; in ~ 'Rote Messe," he tears off

the garments of one priestly order and dedicates himself to another as

eelebrant and Host alike; in "Galgenlied, " he sings of the special intimaey between poets and death and in both "Enthauptung" and "Die

Kreuze" of the agony of poetic creation. Here, Pierrot reaps the cansequenees of three aetions in the first group: the draught of moonlight

so greedily imbibed in "Mondestrunken," the seduetion so desperately

desired in "Colombine," and the disguise assumed in "'Der Dandy"

when he rejeets the past.

With the beginning of the third eycle, the tone of the poetry changes.

Pierrot hears a crystalline chiming sigh ... the word "crystalline n is an

indieation that the sound comes from the past ... and, hearing it, forgets his sorrow: "Da vergisst Pierrot die Trauermienenl"-Hartleben

emphasizes the infusion of new hope and meaning with an exuberance

not found in the more restrained Giraud. The floods of moonlight"eine Springflut" in number one and "lichtmeers Fluten" in number

fifteen-banished from the second cycle reappear, and the time of artistic

rebellion and sterility ("durch seines Herzens Wste"-the heart, the

seat of the emotions, not the head) is over. Hartleben obviously understood the artist's relationship to the past in Giraud's volume and underscores it with a signifieant change of wording in his translation:

Comme un doux soupir de cristal

L'ame des vieilles comedies

Se plaint des allures raidies

Du lent Pierrot sentimental.

Lieblich klagend-ein kristallnes Seufzen

Aus Italiens alter Pantomime,

Klingts herber: wie Pierrot so holzern,

So modern sentimental geworden.

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT UiSAfRE

113

The note of mingled lamentation and accusation ("klagend")-the "oid

pantomime" has missed the clown and mourned his absence-is placed

first, and the recurring "k" consonants lend a klingendes') quality

lacking in the original Freneh. lt is the identification of Pierrot's spiritual

and poetic maladies with modernism, however, that distinguishes Hartleben's diamond from Giraud's du1ler are and brings the allegory into

sharper foeus at this, the turning point of the work.

In the final group of songs, the poet-Pierrot, no longer co\vering

beneath the moon in fear, masters poetry and uses it to affeet others.

In Gemeinheit!", he drills open Cassander's bourgeois skull, despite the

Philistine's piercing screams of protest, stuffs Turkish tobacco into the

grisly opening, and calmly smokes away. Just as the moon, the souree

of poetry, is an intoxicant in the first poem of Op. 21, so Pierrot's

tobacco ... exotic and Turkish, like the scimitar in HEnthauptung" ...

acts on the reluctant Cassander like an intoxicant, fiHing the brain with

fumes of poetry. Again in ~'Serenade," Pierrot plays upon the outraged

and un\villing Cassander, the insensitive buffoon his favorite target anee

more. The Picasso-esque clown's sadness and awkwardness, the mien of

a stork standing on one leg, are in contrast to the delicacy and sureness

with whieh he plays the viola. The grotesque and gigamic bow-Giraud's

shocking, violent imagery?-is necessary because ordinary instruments

cannot move such as Cassander; only the exaggeration of grotesquerie

can force them to take notice and reaet.

After Pierrot hears the VOlee of the pas! and remembers his origins

in "Heimweh," number flfteen, there follows a group of poems in which

he must accept, however sadly or resentfully at times, his identity as a

poet. Only then can he begin the journey to his homeland in "Heimfahrt," the next-to-Iast lied in Op. 21. In number eighteen, "Der Mondfleck," he sets out to seek that which others wha are not poets seek,

fortune and adventure, but he discovers that his black garb (black again)

is indelibly stained with moonlight. Try though he might to rid himself

of the spot, he cannot ... he is rnarked as a poet. Significantly, the SPOt

is on the back of his garment, where he can only see it with difficulty,

but others can easily see it. He does not, one notices, attempt to remove

the garment itself.

Onee Pierrot arrives back horne in the last poem, "0 alter Duft

aus Mrchenzeit, " the "Gelste, schauerlich und sss" of number one

become "Ein narriseh Heer von Schelmerein" that vanishes in the breeze,

and the "Duft, Errinrung mordend" of number eight is replaced by the

"alter Duft aus Mrchenzeit." The dawn of "Heimfahrt" turns to day,

and the poet's "Unmut" disappears through a sunlit window, the opposire of the "Gelste" that descend with the rays of rnoonlight at the

114

SUSAN YOCE?\S

beginning of the tale. The fairy-tale props of the journey horne to Bergamo-a ray of moonlight as a rudder and a waterlily as a boat-belong

to a ~'Mrchenzeit," an enchanted past that Pierrot reclaims. "Ein Mondstrahl"-poetry-is the rudder or guide by which he returns to "die liebe

Welt" and to happiness; for the first time, the real warId, sunlit and

beautiful, shines forth in all its glory, no longer hideously transformed

by moonlight misused.

In conclusion. Op. 21 is, at its core, the narration of an artist's

rejection of and reconciliation with his past, of the spiritual violence

that comes from the attempt to obliterate tradition and therefore to

deny who and what one iso Looking back at the time when Schoenberg

was working on the composition of Pierrot lunaire~ the significance seerns

both personal and historieal, an exemplum of the artistic rebellion against

tradition before World War land a foreshadowing of the chaos of the

war itself and the longing for order that followed. For Schoenberg, who

told his students "Bach is the father of us all," who set "Nacht" -the

beginning of the nightfall of anarchy-as a passacaglia, awareness of the

past and it5 synthesis with the newer musical vocabularies of achanging

world were seemingly always present, but, for all the perils of biographical fallacy, there might have been a more personal meaning to the allegorical journey of Pierrot Poet-Artist-Composer as weIl. Giraud's pi!grimage apparently ended with the acceptance of the Parnassian creed,

but Schoenberg's journey "nach Bergamo, zur Heimat" was far more

intensive, ending only with his death.1!Il

Notes

'Albert Giraud, Pierrot lunaire, trans. by Otto Erich Hartleben (Beriin: Der Verlag

Deutscher Phantasten, 1893).

"'Bhmischer Krystall"

Ein Strahl des Mondes, wohl verschlossen

Im Glass von bhmischem Krystall,

Ein Kleinod, wundersam und selten,

Ist dieses versetolle Buch.

Ich hab mich als Pierrot verkleidetIhr , die ich liebe, bring ich dar

Den Strahl des Mondes, wohl verschlossen

Im Glas von bhmischem Krystall.

In diesem schimmernden Symbole

Liegt Alles, was ich hab und bin.

Gleichwie Pierrot im bleichen Schade!,

Trag ich in Herz und Sinnen nur

Den Strahl des Mondes-wohl verschlossen.

JSee Allardyce Nicoll, The World 01 Harlequin: A Critica! Study of the Commedia

deli' Arte (Cambridge University Press, 1963), p. 87.

THE TEXTS OF PIERROT LUNA!RE

115

"See Robert F. Swrey, Pierrot: A CriricaI HislOry of a Mask (Princeton University

Press, 1980).

'Nicoll, ap. eil., p. 93. For abrief period dming the firs( decade of the eighteenth

century, Watteau was the apprentice of the Parisian painter Claude Gillot, a member

of the Royal Academy. After GHlot introduced Watteau to the theatrical world, the Italian

troupe in Paris was thereafter one of his most frequent subjects, induding the Artequin

galant, Sous un habit de Mezzetin (1717?) in the Wallace Collection, L 'amour au thilitre

italien (circa 1714) in Berlin, a painting in the Charlottenburg Castle in Berlin of a group

of Italian comedians at rest on the stone terrace of achateau, Le Docleur irOuvanl sa

filIe en feste ii teste avec son amant of 1706, Les ja/oux (1712?), depicIing Pierrot and

five mher mascherare, Le Parlie quarree (1712), and others.

'There is a marked resemblance between the face of Gilles in Gil!es and Waneau's face

in a drawing by Fraw;:ois Boucher after a lost self~portrait by Waneau.

7Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, French Eighteenth Century Fainrers (N.Y.: Cornell

University Press, 1981, first ed. Phaidon Books 1948), trans. by Robin lronside, p. 38.

~See Jules Gabriel Janin, Deburau: Histoire du Thelitre d qualre sous (Paris: Librairie

des Bibliophiles, 1881, firs[ ediEion, 1832). Janin describes the characrerization of Pierrot

as Deburau's greatest triumph, and he indudes the complete scenario for a highly complex

entenainment in ten scenes entitled "Ma Mere ['Oie ou Arlequin et l'oeuf d'or": Pamomirne-Arlequinade-Feerie a grand spectade." See also "Pierrm and Fin-de-Siec!e" bv

A. G. Lehmann in Romantic Mythologies, ed. by lan Fletcher (London: Routledge &.

Kegan Paul, 1967), pp. 209-223, also "The Sad Clown: some nates on a nineteenth-cenwry

myth" by Francis Haskeil in French .Nineteenth Century Painting and Literarure, ed. by

Ulrich Finke (Manchester University Press, 1972), p. 2f.

9Charles Baudelaire, "L'Essence du rire et generalemem du comique dans fes arts

plastiques" from Oeuvres completes: Curiosires esthetiques, eG. by Jacques Creper (Paris:

Louis Conard, 1923), p. 389. Baudelaire contrasts the Pierrot of Deburau wirh an EogEsh

pantomime performance at the Theatre des Varietes that made a great impression On hirn.

'VThe first of the articles on Baudelaire appeared on 15 September 1881.

"Adolphe Willette, Feu Pierrot 1857-19? (Paris: H. Floury, ed., 1919).

:~Theodore de Banville, Dans Ja Fournaise: Dernieres Poesies (Paris: BibliothequeCharpentier, 1892), pp. 124-125.

iJEach of Guillemot's three dixains and the envoi, a cinquain, ends with the line,

"Ils sautent en rand sous la lune blanche." The pack of phantom Pierrors in Guillernot's

poem is compared in the second stanza to a fIock of swans, and their gathering is called

"ce pale sabbat" ... cliehes of literary Paris in the Decadence.

Paris: Librairie ancienne et moderne, 1881. Hennique and Huysmans Wrote this

comedie as a mixture of indications for the stage sets, descriptions of the pantomime

action, and actual dialogue.

"In "Sonnets et autres vers" from Jadis in Oeuvres poetiques comp!etes, ed. by Y.-G.

Le Dantec, ed. revised by Jacques Borel (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1962), pp. 320-32l.

'~Brussels: Veuve Monnorn, 1887. Heros et Pierrots was published in a volume that also

contained the earlier Pierrot works, Pierrot lunaire, "Pierrot Narcisse," and Les Dernieres

Feres (Paris: Collection des Poetes frano;ais a l'etranger, 1898).

t 'See Luden Christophe, Albert Giraud: Son

Oeuvre er son remps (Brussels: Palais

des Academies, 1960), p. 16.

'~Hans Landsberg, "Otto Erich Hartieben" in Moderne Essays, ed. by Landsberg

(Berline: Gose & Tetzlaff, 1905). "Auch in Hanleben wohnen zwei Seelen: die eine zum

Spott und zur Karikatur ... die andere, von der Ahnung dunkler Tiefen erfllt ....

He has almost nothing to say about Pierrot lunaire. Cesar Flaischlen, in OUo Erich Hartleben: Beitrag zu einer GeschiChte der modernen Dichwng (Berlin: S. Fischer, 1896), p. 18.

Flaischlen, a friend of Hartleben's, a fellow poet, and the editor of the literary periodical

Pan, obviously could not begin w fathom PierrOl lunaire and says on!y, "Das Ganze

aber ist ein Buch, nur fr-Verrckte" (p. 44).

"Otta Erich Hartleben, Briefe an Freunde, ed. by Franz Ferdinand Heitmueller (BerEn:

S. Fischer, 1912), pp. 162-163.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- 1st Q Examination in ENGLISH 7 (2018-2019)Document13 pages1st Q Examination in ENGLISH 7 (2018-2019)MylenePas encore d'évaluation

- 21th Literary WritersDocument35 pages21th Literary Writerscris_dacuno0% (2)

- Final Draft Essay 2Document9 pagesFinal Draft Essay 2api-581419860Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Student's Writing Guide - CambridgeDocument10 pagesA Student's Writing Guide - CambridgesylviakarPas encore d'évaluation

- Blake's HumanismDocument5 pagesBlake's Humanismرافعہ چیمہPas encore d'évaluation

- Auden As Poet of ThirtiesDocument5 pagesAuden As Poet of ThirtiesKaramveer Kaur ToorPas encore d'évaluation

- NO IMPORTA - Ramesh BalsekarDocument159 pagesNO IMPORTA - Ramesh Balsekarsusana_barcelonaPas encore d'évaluation

- B.A. English Literature SyllabusDocument91 pagesB.A. English Literature SyllabusS. GnanaprakashPas encore d'évaluation

- DomaldeDocument3 pagesDomaldedzimmer6Pas encore d'évaluation

- George T. Dennis (Trans) The Letters of Manuel II Palaeologus PDFDocument317 pagesGeorge T. Dennis (Trans) The Letters of Manuel II Palaeologus PDFJelena Popovic67% (6)

- Revealer of The Fourfold SecretDocument151 pagesRevealer of The Fourfold SecretCatGhita100% (2)

- Weight of Components For Grade 1 To 10: Written Work Performance Task Quarterly AssessmentDocument5 pagesWeight of Components For Grade 1 To 10: Written Work Performance Task Quarterly Assessmentelisa hinesPas encore d'évaluation

- Translation in Comparative Literature: DR Sunitha AnilkumarDocument2 pagesTranslation in Comparative Literature: DR Sunitha AnilkumarqamaPas encore d'évaluation

- Contemporary Poetry 1Document22 pagesContemporary Poetry 1lizzettejoyvapondarPas encore d'évaluation

- Stages of Reading DevelopmentDocument12 pagesStages of Reading DevelopmentMary Ann PateñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jacob Van RuisdaelDocument15 pagesJacob Van RuisdaelAnonymous 4FVm26mbcOPas encore d'évaluation

- Prólogo Lais María de FranciaDocument7 pagesPrólogo Lais María de Franciaisabel margarita jordánPas encore d'évaluation

- Arun KolatkarDocument10 pagesArun KolatkarSoma Biswas0% (1)

- The Storytelling Traditions of Ireland:: Univerza V Ljubljani Fakulteta Za Družbene VedeDocument13 pagesThe Storytelling Traditions of Ireland:: Univerza V Ljubljani Fakulteta Za Družbene VedeVjera ŠestanPas encore d'évaluation

- gr-8 Cisce Eng-Lit Term-1 Sample-PaperDocument5 pagesgr-8 Cisce Eng-Lit Term-1 Sample-PaperAbhi PPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sat Essay 2017Document14 pagesThe Sat Essay 2017zack rickabaughPas encore d'évaluation

- (Continuum Studies in Continental Philosophy) Luchte, James - Nietzsche, Friedrich-Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra - Before Sunrise-Bloomsbury Academic - Continuum (2008)Document230 pages(Continuum Studies in Continental Philosophy) Luchte, James - Nietzsche, Friedrich-Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra - Before Sunrise-Bloomsbury Academic - Continuum (2008)JulianvanRaalte340Pas encore d'évaluation

- May Day Eve ReviewerDocument3 pagesMay Day Eve ReviewerJed Riel Balatan100% (1)

- Literature Review On PoetryDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Poetryc5rh6ras100% (1)

- ADocument70 pagesAAndrea NavarroPas encore d'évaluation

- Project TeamsDocument10 pagesProject Teamspooripresident123Pas encore d'évaluation

- Mann, Thomas - Essays of Three Decades (Alfred A. Knopf 1947 1948)Document502 pagesMann, Thomas - Essays of Three Decades (Alfred A. Knopf 1947 1948)georgesbataille90% (10)

- Keats and ShelleyDocument16 pagesKeats and Shelleysncmusic22Pas encore d'évaluation

- Waka and Form, Waka and History Author(s) : Mark Morris Source: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Dec., 1986, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Dec., 1986), Pp. 551-610 Published By: Harvard-Yenching InstituteDocument61 pagesWaka and Form, Waka and History Author(s) : Mark Morris Source: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Dec., 1986, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Dec., 1986), Pp. 551-610 Published By: Harvard-Yenching InstituteDick WhytePas encore d'évaluation

- Creative Nonfiction HAND OUTDocument4 pagesCreative Nonfiction HAND OUTJane Sagutaon100% (1)