Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Lawrence Doly Scotland

Transféré par

aalgazeCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Lawrence Doly Scotland

Transféré par

aalgazeDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Scotland on the Dole

Lawrence Daly

Scotland draw your swordfor youve drawn the dole long

enough! This cry of the thirties echoes again throughout Scotland

today. The Scottish people feel that they are getting the rawest of

raw deals and that this is due to the incompetence and indifference of

Whitehall and Westminster. This explains the large Nationalist vote

at West Lothian where the Scottish Nationalist Party candidate came

second and caused both the Tories and the Liberals to lose their

deposits.

It is no use telling the Scots that their economic problems are

similar to those of Lancashire or Durham. They will agree, but will

add that if the English cant run their own affairs properly that is no

reason why they should continue to mismanage those of Scotland.

They believe that the answer lies, ultimately, in the restoration of a

Scottish Parliament. When young Scots are politically enthusiastic

today they are to be seen sporting Ban-the-Bomb badges or Free

Scotland badges, or both at the same time.

Random interviews by Scottish Television have indicated almost

unanimous support for the Scottish Plebiscite Committee which is

very actively raising cash for an all-Scottish plebiscite on the selfgovernment question.

Socialists should not dismiss this feeling as an amusing piece of

quaint, Celtic revivalism. Its economic and psychological roots are

deep and its relevance to the problem of democratic government and

social planning is immediate and significant.

Since the first World War Scotland has had to bear a disporportionate share of Britains unemployment. With 10 per cent of

Britains population, she usually has 20 per cent of its unemployed

workers. This is mainly due to the fact that her traditional industries

coal, steel, shipbuilding and heavy engineeringwhich once gave

her a relative advantage, have been in decline for over 40 years. The

planned introduction of new industries and the rationalization,

integration, and modernization of existing ones, which could have

cured her chronic economic condition, either never took place or if it

did was started too late. Even before 1914, the writing was on the

wall, for her economy centred more and more on the coal-producing

18

Forth-Clyde Valley and drew her skilled agricultural workers and

craftsmen away from the countryside, depopulating the Highlands

and Islands in the process, and devitalizing her folk culture. She had

her industrial coffin before England and is now suffocating from

the stench of economic obsolescence. While the Midlands and SouthEast of England attracted the modern industriesmotor-cars, cycles,

radios, television, plastics, packaging, tinned foods, etc.Scotland

remained perilously dependent on the older industries, which are now

facing acute crisis.

This years Report on Industry and Employment in Scotland

describes the outlook for shipbuilding and marine engineering as

far from promising. Partly because of this, the Scottish steel

industry is operating at only 60 per cent of its capacity. Beechings

rail closure plans threaten to leave practically the whole of Scotland

north of Perth dependent on an inadequate network of roads. The

N.C.B.s recent review indicates that only 46 of Scotlands 106

remaining pits will be left by 1966, if Lord Robens has his way.

One hundred and seventy of them have been closed down since 1945.

In September, 1962, unemployment reached nearly 83,000. The

Scottish Council for Development and Industry has warned that the

figure will reach 100,000 by January, 1963. The Council, which contains representatives of Scottish industry, the banks, the local

authorities, and the Scottish T.U.C., completed at the end of 1961

its own enquiry into the Scottish economynow known as the

Toothill Report. Dominated as it is by Scottish capitalists, the Council

rejected any proposals that involved extended public ownership or

Scottish self-government. Nevertheless, their criticisms of Scottish

industry and of the failure of the Westminster Government to give

adequate inducements and assistance to it, strengthen the case for

social control of the economy and for a degree of self-government

sufficient to overcome the evils of bureaucratic centralization.

The Council was stung to anger by the Governments refusal to

accept its modest proposals and has embarked on a campaign to

enforce their acceptance and implementation. The Scottish T.U.C. is

also campaigningfor the more robust policy of direction of industry.

Full support is being given by the affiliated unions, especially the

Scottish N.U.R. and N.U.M., who are righting against rail closures

that would affect essential services and against pit closures in cases

where coal reserves could be worked until alternative industry is

established.

Meantime, growing redundancy, short-time working, and the general insecurity, sends Scots out of their native land in ever-increasing

numbers. In the last 10 years the average net annual migration from

Scotland was 25,000. But by 1961 it reached over 34,000, 15 per cent

of them going abroad and the rest moving down into the already

overcrowded and congested areas of England. It is the young and the

skilled, in the main, who are moving; so that the economic loss to

Scotland is a very heavy one; and so is the economic burden (carrying

a bigger proportion of old people) that remains. Yet these social and

economic consequences are blandly ignored by the Government, and

Scotland on the Dole

the profit yardstickrather than that of social needis ruthlessly

applied, even to the publicly-owned industries. The disastrous drift

of population is in fact being actively encouraged. The N.C.B. is

widely advertising its transfer scheme and trying with all its might to

get Scottish miners into the Midlands. The local newspapers also

carry large adverts offering attractive inducements to get the more

skilled miners out to Ghana, Uganda, etc., as well as the older

Commonwealth countries.

Most of those who yield to these heavy pressures and temptations

do so reluctantly and, indeed, with heavy hearts. Substantial though

their numbers are, what is really surprising and impressive is the

way in which the vast majority of the people refuse to be uprooted.

They take the view that if the Israelis can develop the desert and the

Brazilians the jungle, the Scots if given half a chance can develop

new enterprises in Scotland. They are highly conscious of the

Governments responsibility (and irresponsibility) in this respect and

are determined that it, or a succeeding Government, must be compelled to face up to the problem.

They are particularly incensed by the frustration that confronts

the teen-ager. In September, 1962, 7,289 people under 18 years of

age were in the dole queues, 4,589 of them boys, 2,700 girls. Of these

2,714 were school-leavers. The teaching profession is up in arms

against this ridiculous waste of its talents. At conferences and

demonstrations, even while professing no interest in politics, they

have scathingly denounced the Government for not ensuring that

the skill and energy of their ex-pupils is utilized. Youngsters kick

their heels all day at the street corners and yet some people wonder

why vandalism is increasing! They leave school at the age of 15 but

find that they cannot get paid Unemployment Benefit until they

have 26 stamps on their card; and they cannot get 26 stamps on

their card until theyve been six months in employment. They turn,

hopefully, to the National Assistance Board who then inform them

that they cannot receive an assistance allowance until they have

reached 16 years of age! The parents are advised that they must

accept full responsibility for the young unemployed persons

maintenance. Resentment is added to frustration. The boy or girl

wants the same clothes and pocket money as those young friends

who are fortunate enough to have a job. The parent worries about

the effect on a family income already depleted by the reduction in

earnings opportunities.

Some of the young people have got organised to insist that constructive use will be made of their talents. For example, in West Fife,

helped by the Youth Employment Officer at Cowdenbeath, they

have formed an Economic Development Council to agitate for the

clearing of derelict areas, special training of young people for new

industries, and other measures. They live in a region that is being

hit harder than any other by pit closures and they are determined to

avert its harsh consequences. But they know that they have a hard

battle ahead. For every pit in Central West Fife is under threat of

closure by 1966. The programme of closures is already under way.

20

Six thousand men will be affected. All that has appeared, to provide

alternative, are two small factorieswhich will employ women almost

exclusively; and this will only partly compensate for loss of female

jobs due to factory closures in the outlying towns of Kirkcaldy and

Dunfermline.

Many of the local authorities are doing their best to cope with a

very difficult situation. Midlothian County Council is building advance factories. Two days after the West Lothian result the Government announced that it would provide six advance factories for the

whole of Scotland but these, if and when completed, will only

scratch the surface of the problem.

The Fife County Council in particular has reacted swiftly and

angrily. 17 million of social capital they have invested since the

end of the war, in new housing schemes, clinics, libraries, and schools,

is in danger of being left to decay in an economic desert. So they

have demanded positive action by the Government. And they

havent pulled their punches. They organised an all-Fife conference

to discuss the problem and demanded direction of industry. Fife

County Council, like many others, is expanding its publicity

services in the hope of attracting industrialists and is embarking on

a series of face-lifts to clean up derelict villages and old colliery

spoil-heaps, in addition to preparing sites for factories. But the

tolls that the Government still insists shall be paid on the Forth

Road Bridge are a formidable obstacle to the attraction of new

industries. No final decision has yet been taken but charges of 5s. to

8s. per vehicle for a single crossing are being considered. Fife County

Council has won wide support for its campaign against this economic

lunacy.

At the end of August when F. J. Errol opened the Industrial

Estate at Donibristle in Fifeon which there is as yet no industry,

nor even applications to buildthe County Convener said to him,

We as a local authority cannot give an enquiring industrialist the

slightest guide as to the financial assistance to which he might be

entitled should he decide to set up a factory. Is there any reason why

we cannot be allowed to do so? If an industrialist goes to Northern

Ireland he can be told in five minutes precisely what he can obtain.

Have we got to send 71 Nationalist MPs to Westminster before it

happens here?

The Conservative Dunfermline Presss editorial commentunder

the heading Jam To-morrow?accused Errol of uttering every

clich in the book. It described the ceremony as a mere perfunctory

goodwill gesture in the game of kidology which the Government

is playing to give the impression that it is doing something for

Scotland, and concluded, We have had enough platitudes to last

us for a life-time. Now what we look for is actionnot words.

Jobsnot promises!

This hard-hitting attack is typical of almost the whole of the

Scottish presseven Roy Thomsons The Scotsman has participated in the campaign. Speaking of the railwaymens strike on

October 3rd, its editorialist said The Government must also come

Scotland on the Dole

under censure for their handling of affairs. It would not seem that

when the Government issued their financial directive to the

nationalised industries requiring them to balance their accounts they

gave much thought to the economic problems that would arise, or

to the need to create alternative employment for the workers who

would lose their jobs.

These reactions reflect the fears of Tory MPs and business-men

who see their Party facing a political catastrophe in Scotland. They

shudder at the word Socialism but some of them will tolerate

even demandsome Socialistic measures if it will save them from

electoral disaster. The Scottish Board for Industry, for example, has

demanded that one of the two big power stations planned for

South-East England should be sited in Scotland. Private industry has

shown that it will only come in if its pockets are well-lined. All the

big new projects in Scotland under private enterpriselike

Colvilles strip-mill at Ravenscraig, BMCs factory at Bathgate,

and Rootes at Linwoodare receiving lavish financial assistance

from the Government, much of it in interest-free loans or direct

grants. British Oxygen Ltd. were offered million but still refused

to come in. Bigger bribes are being demanded.

The situation has led to the resurrection of Samuel Smiles. In

Cowdenbeath the so-called Ratepayers Association (usually a

euphemism for local Tory municipal candidates) has started a doorto-door canvass to get people to buy 5/ shares to bring a new

factory into the town. Across the Forth, in West Lothian, new

Labour MP Tam Dalyell offers a 5,000 loan of his own cash for a

similar project and gets a mammoth meeting in Boness to discuss,

and accept, his proposals for local share-buying. But the money

available, even if readily subscribed, can only bring in a tiny fraction

of the jobs required. The Tories repeatedly give the assurance that,

under the Local Employment Act, plenty of jobs are in the pipeline.

But they never say how long the pipeline is or how far from the

delivery end the jobs are. Nor do they say how many jobs are

disappearing down the out-going pipelines. In the last 12 months

Scotland got 20,000 new jobs. But 25,000 other jobs disappeared!

A group even more tragically placed are the disabled workers, who

find themselves on light jobs which, because of the surplus manpower available, can only command wages that are so low that they

are often below the minimum subsistence level laid down by the

National Assistance Board regulations. Those who cannot find

suitable light work have their weekly allowance from the Board

cut to below subsistence level to bring them in line with the level of

average light work earnings in their own particular district. This

most seriously affects the chronically sick.

The low rates paid to day-wage workers in the mining industry

were often supplemented by overtime earnings. But since 1958 the

NCB have rigorously restricted overtime and many families have to

live on incomes of less than 9 and 10 per week. The men concerned

feel betrayed, both by the NCB, and by their own trade union for

failing to enforce a reasonable minimum wage when its bargaining

22

strength was at its greatest, in the 194757 period. The rewards they

got from the industry have never been commensurate with their

labours and they have no desire, therefore, to see the pits stay open,

provided they are given alternative means of earning a secure

livelihood. The growth of unemployment and the reduction in

earnings has been a big blow to the small shopkeepers, multiple firms

and the Co-ops. The latter have been particularly responsive to the

campaign of the unions for the direction of new industries into the

affected areas. They have supported the protest demonstrations and

meetings wholeheartedly. But, so far, the Scottish Co-operative

Wholesale Society has not considered it possible to help by expanding

its productive operations into such areas. There is still a very strong

tendency in the Co-operative movement to take an extremely narrow,

commercial view of its functions. To what extent is this true of

England? How far have our brothers in the south succumbed to the

deadly attraction of the coffin? Cannot something be done through

the National Council of Labour and the Co-operative Union to

secure some re-distribution of Co-op finance and investment, even

in the form of low-interest loans? If such were possible it could lead,

incidentally, to an extension of one form of public ownership that is

more amenable to democratic control. An expansion of public works

by local authorities could also provide some temporary alleviation.

For political reasons, St. Andrews House is likely to be readier to

sanction these in 1963. But how many local authorities, including

Labour-controlled ones, will make the best of the opportunity?

In housing alone a big expansion in building is necessary. The

Scottish housing construction programme was seriously cut by the

Tories, from 34,000 in 1955 to 27,000 in 1961; and in the first half

of 1962 it was running substantially below that rate. Of these the

number built by local authorities dropped from 24,000 in 1955 to

16,800 in 1961. Yet the waiting lists in many places are longer than

ever and slum clearance proceeds at a snails pace.

The Toothill Committee estimated that Scotland required a net

gain of 20,000 jobs for each 1 per cent reduction in unemployment.

It has become increasingly recognised that their provision will

involve the adoption of an overall economic plan for Scotland. The

Scottish Trade Union Congress has now demanded this. In a speech

at Aberdeen on 7th October its General Secretary, Mr. George

Middleton, said, We have a separate education system, a separate

agricultural department, separate jurisprudence. Why shouldnt we

have something economic? This is a step on the road to the policy

adopted in 1960 by the Annual Conference of Scottish NUMthat

of demanding a Scottish Parliament with control of Scottish affairs.

Many Socialists consider that this demand runs counter to their

internationalism. Yet they enthusiastically support every movement

for national independence overseas. Scotsmen watch the emergent

nations, on the morrow of their freedom, taking their place in the

world parliament, while Scotland, with a record of many centuries

as an independent nation, becomes an economic and political

Scotland on the Dole

backwater. They are aware of ludicrously small attendances in the

House of Commons when Scottish affairs are being debated; of the

extremely limited powers of the Scottish Departments in St. Andrews

House, Edinburgh; of the time-wasting coming and going by armies

of bureaucrats between there and London. They see small nations

like Denmark, Norway, Switzerland and New Zealand match

political independence with economic viability. Their own experience

has made them deeply conscious of the dangers inherent in the

centralisation of political or economic power, and of the need to

counter-balance these by the maximum practicable self-government.

Many of them remember that the Party that once recognised all this

was the Labour Party; that one of the greatest advocates of Scottish

Home Rule was Keir Hardie; and that after 1945 the Labour Party

ditched its own policy. It is for this reasonand this reason alone

that they are tending to voice their protest by voting for the Scottish

National Party. They know that in many other respects it is unworthy

of their support. It is against any extension of public ownership,

it is for Polaris and Nato, and it is in favour of entry to the Common

Market. Its adherents are referred to as The Tartan Tories.

If the Labour Party were to once again give expression to the

demand for self-government, the vast majority of the Scottish people

would sweep aside Tartan and non-Tartan Tories alike in a powerful

surge of support for Labour. A Scottish Parliament would certainly

contain a majority of Labour and radical members. There is every

chance that it could not only revitalise Scotlands economic and

cultural life but that it might well set the pace for the progressive

social transformation of the rest of Britain.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Racial and Ethnic Groups 13e - BMDocument51 pagesRacial and Ethnic Groups 13e - BMpsykhoxygen0% (1)

- Menace of The Irish Race To Our Scottish NationalityDocument8 pagesMenace of The Irish Race To Our Scottish Nationalitypetitioner83% (6)

- Scottish Independence HomeworkDocument5 pagesScottish Independence Homeworkh41wq3rv100% (1)

- Béal Feirste Thoir-Theas Eanáir 2012Document2 pagesBéal Feirste Thoir-Theas Eanáir 2012eirigi_bfPas encore d'évaluation

- E Newsletter October 2012 PDFDocument2 pagesE Newsletter October 2012 PDFPhyllis StephenPas encore d'évaluation

- E Newsletter February 2012Document2 pagesE Newsletter February 2012Phyllis StephenPas encore d'évaluation

- Economic Development of Caricom: From Early Colonial Times to the PresentD'EverandEconomic Development of Caricom: From Early Colonial Times to the PresentPas encore d'évaluation

- Main Report On IcelandDocument9 pagesMain Report On IcelandNazia SultanaPas encore d'évaluation

- 1916: One Hundred Years of Irish Independence: From the Easter Rising to the PresentD'Everand1916: One Hundred Years of Irish Independence: From the Easter Rising to the PresentÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- Historynotes Theme8Document11 pagesHistorynotes Theme8JM Mondesir86% (7)

- Implementing Equal Opportunities - A 30 Year Case-StudyDocument7 pagesImplementing Equal Opportunities - A 30 Year Case-Studyronald youngPas encore d'évaluation

- Free Liberal Yorkshire ManifestoDocument7 pagesFree Liberal Yorkshire ManifestoHeidi ZamoraPas encore d'évaluation

- Article On Scottish Independence FinalDocument7 pagesArticle On Scottish Independence FinalisscotlandPas encore d'évaluation

- Irish Water To Get 660m BailoutDocument131 pagesIrish Water To Get 660m BailoutRita CahillPas encore d'évaluation

- Problems of Urban Growth in LedcsDocument5 pagesProblems of Urban Growth in Ledcsapi-25904890Pas encore d'évaluation

- A New Life in our History: the settlement of Australia and New Zealand: volume II Paradise Found ? (1830s to 1890s)D'EverandA New Life in our History: the settlement of Australia and New Zealand: volume II Paradise Found ? (1830s to 1890s)Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Statement About ScotlandDocument5 pagesThesis Statement About Scotlandcrystalharrislittlerock100% (3)

- B / Economic ProfileDocument22 pagesB / Economic ProfileEmmanuel dupont the greatPas encore d'évaluation

- Glenrothes 1948 To 1998. A Geographical Study of The 'New Town' in Its 50th Year. Malcolm Sutherland, 1998Document21 pagesGlenrothes 1948 To 1998. A Geographical Study of The 'New Town' in Its 50th Year. Malcolm Sutherland, 1998Dr Malcolm SutherlandPas encore d'évaluation

- The Citizens Party of Australia ManifestoDocument45 pagesThe Citizens Party of Australia ManifestoRishitPas encore d'évaluation

- Werabull April 20Document3 pagesWerabull April 20api-513624732Pas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Even It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentDocument28 pagesEven It Up: Scotland's Role in Tackling Poverty by Reducing Inequality at Home and Abroad - Oxfam's Policy Priorities For The Scottish ParliamentOxfamPas encore d'évaluation

- Therborn Clases An Welfare StateDocument35 pagesTherborn Clases An Welfare StateaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Susan Willis Captured by The ScreenDocument5 pagesSusan Willis Captured by The ScreenaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Blixen Pinochet Mad ScientistDocument7 pagesBlixen Pinochet Mad ScientistaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Therborn Clases An Welfare StateDocument35 pagesTherborn Clases An Welfare StateaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Communication The World Economic Crisis NLRDocument3 pagesCommunication The World Economic Crisis NLRaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Branka Magas Sex Politics: Class PoliticsDocument24 pagesBranka Magas Sex Politics: Class PoliticsaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Lee Rusell Cinema Code and ImageDocument17 pagesLee Rusell Cinema Code and ImageaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Theory of The Partisan by Dr. Carl SchmittDocument78 pagesTheory of The Partisan by Dr. Carl SchmittSnowfall100% (7)

- Spain - The Untimely RevolutionDocument30 pagesSpain - The Untimely RevolutionaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Ben Brewster Armed Insurrection and Dual PowerDocument10 pagesBen Brewster Armed Insurrection and Dual PoweraalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- NLR02810 PDFDocument12 pagesNLR02810 PDFaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- John Keane The Polish LaboratoryDocument8 pagesJohn Keane The Polish LaboratoryaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- E.P. Thompson - RevolutionDocument7 pagesE.P. Thompson - RevolutionFalossPas encore d'évaluation

- Liu Bynian Future of ChinaDocument12 pagesLiu Bynian Future of ChinaaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Gluksmann NLRDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Gluksmann NLRaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Benton Yenan Literary Oposition PDFDocument4 pagesBenton Yenan Literary Oposition PDFaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- NLR13302 PDFDocument26 pagesNLR13302 PDFaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Jean Gardiner Women's Domestic LabourDocument12 pagesJean Gardiner Women's Domestic LabouraalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Kate Soper Love's WorkDocument6 pagesKate Soper Love's WorkaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Regis Debray - The Long MarchDocument42 pagesRegis Debray - The Long MarchTias BradburyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ernest Mandel ObituaryDocument4 pagesErnest Mandel ObituaryaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Benedict Anderson The New World DisorderDocument11 pagesBenedict Anderson The New World DisorderEffie Fragkou100% (1)

- NLR14404 PDFDocument30 pagesNLR14404 PDFaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- 445 PDFDocument44 pages445 PDFaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Inti Peredo Guerrilla Warfare Bolivia 1968Document10 pagesInti Peredo Guerrilla Warfare Bolivia 1968aalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Gunnar Myrdal Paths of DevelopmentDocument10 pagesGunnar Myrdal Paths of DevelopmentaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Gareth Stedman Jones History in One DimensionDocument11 pagesGareth Stedman Jones History in One DimensionaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Martin RossdaleDocument23 pagesMartin RossdaleaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Lucien Rey Dossier Indonesian DramaDocument15 pagesLucien Rey Dossier Indonesian DramaaalgazePas encore d'évaluation

- Montebon vs. Commission On Elections, 551 SCRA 50Document4 pagesMontebon vs. Commission On Elections, 551 SCRA 50Liz LorenzoPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Things To Know About Japanese PoliticsDocument4 pages7 Things To Know About Japanese PoliticsHelbert Depitilla Albelda LptPas encore d'évaluation

- Energy Justice in Native America BrochureDocument2 pagesEnergy Justice in Native America BrochureecobuffaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Registration Form For Admission To Pre KGDocument3 pagesRegistration Form For Admission To Pre KGM AdnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Starkville Dispatch Eedition 11-28-18Document16 pagesStarkville Dispatch Eedition 11-28-18The DispatchPas encore d'évaluation

- Quanta Cura: Opposition To Unrestrained Freedom of ConscienceDocument2 pagesQuanta Cura: Opposition To Unrestrained Freedom of ConsciencewindorinPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Firefighters Die - 2011 September - City Limits MagazineDocument33 pagesWhy Firefighters Die - 2011 September - City Limits MagazineCity Limits (New York)100% (1)

- V524 Rahman FinalPaperDocument10 pagesV524 Rahman FinalPaperSaidur Rahman SagorPas encore d'évaluation

- Nine Lessons For NegotiatorsDocument6 pagesNine Lessons For NegotiatorsTabula RasaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2021revised PYSPESO 11 BTEC Form B Skills Registry System Rev 01Document1 page2021revised PYSPESO 11 BTEC Form B Skills Registry System Rev 01Janna AlardePas encore d'évaluation

- Zizek It's The PoliticalEconomy, Stupid!Document13 pagesZizek It's The PoliticalEconomy, Stupid!BobPas encore d'évaluation

- Arballo v. Orona-Hardee, Ariz. Ct. App. (2015)Document6 pagesArballo v. Orona-Hardee, Ariz. Ct. App. (2015)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Republic of Kosovo - Facts and FiguresDocument100 pagesRepublic of Kosovo - Facts and FiguresTahirPas encore d'évaluation

- Using L1 in ESL Classrooms Can Benefit LearningDocument7 pagesUsing L1 in ESL Classrooms Can Benefit LearningIsabellaSabhrinaNPas encore d'évaluation

- The Forum Gazette Vol. 4 No. 20 November 1-15, 1989Document12 pagesThe Forum Gazette Vol. 4 No. 20 November 1-15, 1989SikhDigitalLibraryPas encore d'évaluation

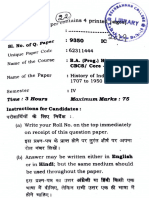

- B.A (Prog) History 4th Semester 2019Document22 pagesB.A (Prog) History 4th Semester 2019lakshyadeep2232004Pas encore d'évaluation

- COA Decision on Excessive PEI Payments by Iloilo Provincial GovernmentDocument5 pagesCOA Decision on Excessive PEI Payments by Iloilo Provincial Governmentmaximo s. isidro iiiPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 3 ConsiderationDocument38 pagesUnit 3 ConsiderationArpita SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Contract LawDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Contract LawTsholofeloPas encore d'évaluation

- Words: BrazenDocument16 pagesWords: BrazenRohit ChoudharyPas encore d'évaluation

- (Advances in Political Science) David M. Olson, Michael L. Mezey - Legislatures in The Policy Process - The Dilemmas of Economic Policy - Cambridge University Press (1991)Document244 pages(Advances in Political Science) David M. Olson, Michael L. Mezey - Legislatures in The Policy Process - The Dilemmas of Economic Policy - Cambridge University Press (1991)Hendix GorrixePas encore d'évaluation

- RP VS EnoDocument2 pagesRP VS EnorbPas encore d'évaluation

- Buffalo Bills Letter 4.1.22Document2 pagesBuffalo Bills Letter 4.1.22Capitol PressroomPas encore d'évaluation

- Manufacturing Consent and Intellectual Cloning at Leicester University - Letter To Dr. RofeDocument57 pagesManufacturing Consent and Intellectual Cloning at Leicester University - Letter To Dr. RofeEyemanProphetPas encore d'évaluation

- Left Gatekeepers Part 2Document20 pagesLeft Gatekeepers Part 2Timothy100% (1)

- Memorandum: United States Department of EducationDocument3 pagesMemorandum: United States Department of EducationKevinOhlandtPas encore d'évaluation

- Do You A College Degree To Get A Job - Debate (Both For and Against) ?Document2 pagesDo You A College Degree To Get A Job - Debate (Both For and Against) ?shreyaPas encore d'évaluation

- East European Politics & SocietiesDocument40 pagesEast European Politics & SocietiesLiviu NeagoePas encore d'évaluation

- PMBR Flash Cards - Constitutional Law - 2007 PDFDocument106 pagesPMBR Flash Cards - Constitutional Law - 2007 PDFjackojidemasiado100% (1)