Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Wod15-Fact Sheet

Transféré par

api-322309995Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Wod15-Fact Sheet

Transféré par

api-322309995Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Nutrition and bone health throughout life Fact Sheet

The big 3: key nutrients for

building strong bones

The amount of calcium we need to consume varies at

different stages in our lives.

Daily calcium intake recommendations for

populations vary between countries but the general

consensus is that people are not consuming enough.

For people who cannot get enough calcium through

their diets, supplements may be beneficial. These

should be limited to 500-600 mg per day and it is

generally recommended that they be taken combined

with vitamin D.

1. Calcium

Vital for strong bones, calcium is a major building

block of our skeleton; 99% of the 1 kg of calcium found

in the average adult body resides in our bones.

Bone acts as a reservoir for maintaining calcium levels

in the blood, which is essential for healthy nerve and

muscle function.

If you dont supply your body with the calcium it

needs, it will respond by taking calcium from your

bones and weaken them.

Certain diseases affect how much calcium is absorbed

by the body i.e. Crohns, coeliac disease, lactose

maldigestion and intolerance.

Milk and other dairy foods are the most readily

available sources of calcium.

Some people have trouble digesting lactose in milk

and dairy, but there are other food sources of calcium

including green vegetables (e.g., broccoli, curly kale,

bok choy); whole canned fish with soft, edible bones

such as sardines or pilchards; nuts (almonds and

Brazil nuts in particular); and tofu set with calcium.

2. Vitamin D

Plays two key roles in the development and

maintenance of healthy bones: helps the body absorb

calcium from the intestines; ensures correct renewal

and mineralization of bone.

Helps improve muscle strength and balance hence

reducing the risk of falls.

Made in the skin when it is exposed to UV-B rays in

sunlight.

Sunlight does not always promote vitamin D

synthesis: the season and latitude, use of sunscreen,

city smog, skin pigmentation, a persons age etc.,

affect how much vitamin D is synthesized in the skin

through sunlight.

Severe deficiency in children can lead to growth

retardation and bone deformities known as rickets.

Deficiency in adults leads to osteomalacia, which is a

softening of the bones due to poor mineralization.

Low population levels of vitamin D are a cause of

concern globally as they can predispose individuals

to osteoporosis.

Dietary sources of vitamin D include: oily fish (e.g.,

salmon, mackerel and sardines), egg yolk and liver. In

some countries milk, margarine and breakfast cereals

are fortified with vitamin D.

Approximately half of our bone mass is accumulated

during adolescence.

While genetics contributes up to 80% of the variance

in peak BMD, modifiable factors such as diet and

physical activity also affect bone mass accrual.

Gender and ethnicity also play a role.

The age of peak calcium accretion is 14 years in boys

and 12.5 years in girls.

Milk and other dairy products are the source of up to

80% of dietary calcium intake for children from the

second year of life onwards.

Recommended vitamin D intakes vary by age group

and needs increase as you age.

Individuals should try to get 1020 minutes of sun

exposure to bare skin (face, hands and arms) outside

peak sunlight hours (before 10 am and after 2 pm) daily

without sunscreen and taking care not to burn.

Children are consuming less milk than they did

10 years ago and this decrease may be related to

increased consumption of sweetened beverages.

Anorexia nervosa negatively impacts BMD and bone

strength.

Overweight and obese children have low bone mass

and area for their weight and are more likely to

sustain repeated fracture at the wrist than normalweight children.

A healthy body weight during childhood and

adolescence contributes to optimal bone health.

3. Protein

Provides the body with a source of essential amino

acids necessary to support the building of bone.

Insufficient protein intake is detrimental both for the

acquisition of peak bone mass during childhood and

adolescence affecting skeletal growth and for the

preservation of bone mass with ageing.

In older adults, low protein intake is associated with

loss of bone mineral density (BMD) one indicator of

bone strength at the hip and the spine.

Protein supplementation of hip fracture patients

has been shown to reduce post-fracture bone loss,

medical complications and rehabilitation hospital stay.

Protein undernutrition leads to reduced muscle mass

and strength which is a risk factor for falls.

The role of micronutrients

Micronutrients are chemical elements or substances

required in trace amounts for the normal growth and

development of living organisms.

There are many micronutrients of importance to

bone health with evidence still emerging on their

benefits, these include: vitamin K; B vitamins and

homocysteine; vitamin A; magnesium; and zinc.

Children and adolescents BUILD

Adults MAINTAIN bone health

and avoid premature bone loss

Bone tissue loss generally begins at the age of 40

years, when we can no longer replace bone tissue as

quickly as we lose it.

Pregnant women must get adequate calcium and

vitamin D, to optimize the development of their

babys skeleton.

Poor pre-natal growth is associated with reduced

adult bone mineral content at peak bone mass and in

later life, and also increased risk of hip fracture.

After menopause, women undergo a period of rapid

bone loss, as bone resorption outstrips formation, due

to the lack of protective oestrogen.

Consuming more than 2 units of alcohol per day can

increase the risk of suffering a fragility fracture, while

more than 4 units per day can double fracture risk.

A body mass index (BMI) <19 is considered

underweight and is a risk factor for osteoporosis.

During adulthood a comparative period of balance

between new bone being formed and old being

removed maintains bone mass. It is important to keep

this balance by adopting bone-healthy behaviours

including getting enough of the correct nutrients.

maximum peak bone mass

Critical time for building bone mass as new bone

is formed more quickly than old bone is removed

causing bones to become larger and denser, this

process continues until the mid 20s.

Building strong bones in early life can make you less

vulnerable to osteoporosis in later life.

A 10% increase in peak BMD may delay the

development of osteoporosis by 13 years.

Seniors SUSTAIN mobility and

independence into your old age

Taking preventative measures including ensuring

a healthy diet will slow the rate of bone thinning

and reduce the risk of having osteoporosis-related

fractures.

In men, bone loss tends to accelerate after the age of

70 years.

Calcium levels may be lower in seniors due to

decreased consumption i.e., poor appetite, illness,

social and economic factors with malnutrition being

common; decreased intestinal absorption of calcium

(exacerbated by low vitamin D status) and decreased

retention of calcium by the kidneys.

Vitamin D levels may be lower because of less

frequent exposure to sunlight for the housebound,

decreased function of the skin to synthesize vitamin D

and decreased renal capacity to convert vitamin D to

its active form.

To maintain physical function, older people need more

dietary protein than the young.

Supplementary protein or higher dietary intake of

protein by older people who have been hospitalized

with hip fracture has been shown to improve bone

density, reduce the risk of complications and reduce

rehabilitation time.

Preventing muscle wasting (sarcopenia) in seniors

is important because it lowers the risk of falls and

associated injuries, including fragility fractures.

People aged over 50 years who have suffered a

previous fracture as a result of a fall from standing

height or less, should speak to their health-care

professional about getting tested for osteoporosis.

Although bone healthy nutrition, exercise, and

avoidance of negative lifestyle habits are important,

drug therapies are critical for fracture protection in

patients at high risk for fractures. A 3050% reduction

in fracture incidence can be achieved with 3 years of

pharmacotherapy.

Controlling osteoporosis risk factors and complying

with treatment regimens, where prescribed, can

ensure seniors live mobile, independent, fracture-free

lives for longer.

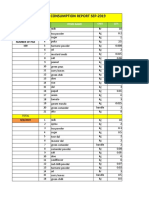

Recommended daily allowances: calcium and vitamin D

Recommended daily allowances (RDA) for populations may vary between countries. The IOM 2010 (Institute of Medicine

of the US National Academy of Sciences) recommendations are shown in the table below.

Life-stage group

Calcium RDA (mg/day)

Vitamin D RDA (IU/day)

Infants 0-6 months

**

Infants 6-12 months

**

1-3 years old

700

600

4-8 years old

1,000

600

9-13 years old

1,300

600

14-18 years old

1,300

600

19-30 years old

1,000

600

31-50 years old

1,000

600

51-70 year old males

1,000

600

51-70 year old females

1,200

600

>70 years old

1,200

800

14-18 years old, pregnant/lactating

1,300

600

19-50 years old, pregnant/lactating

1,000

600

*For infants, adequate intake is 200 mg/day for 06 months of age and 260 mg/day for 612 months of age.

**For infants, adequate intake is 400 IU/day for 06 months of age and 400 IU/day for 612 months of age.

IU: International Unit

The International Osteoporosis Foundation recommends that seniors aged 60 years and over take a supplement at a

dose of 800 to 1000 IU/day for falls and fracture protection.

International Osteoporosis Foundation rue Juste-Olivier, 9 CH-1260 Nyon Switzerland

T +41 22 994 01 00 F +41 22 994 01 01 info@iofbonehealth.org www.iofbonehealth.org

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- S ELITE Nina Authors Certain Ivey This Reproduce Western Material Management Gupta Names Do OntarioDocument15 pagesS ELITE Nina Authors Certain Ivey This Reproduce Western Material Management Gupta Names Do Ontariocarlos menaPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief RESUME EmailDocument4 pagesBrief RESUME Emailranjit_kadalg2011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Staff Food Consumption Reports Sep-2019Document4 pagesDaily Staff Food Consumption Reports Sep-2019Manjit RawatPas encore d'évaluation

- EXP 2 - Plug Flow Tubular ReactorDocument18 pagesEXP 2 - Plug Flow Tubular ReactorOng Jia YeePas encore d'évaluation

- DPA Fact Sheet Women Prison and Drug War Jan2015 PDFDocument2 pagesDPA Fact Sheet Women Prison and Drug War Jan2015 PDFwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti Stain Nsl30 Super - Msds - SdsDocument8 pagesAnti Stain Nsl30 Super - Msds - SdsS.A. MohsinPas encore d'évaluation

- Registration Statement (For Single Proprietor)Document2 pagesRegistration Statement (For Single Proprietor)Sherwin SalanayPas encore d'évaluation

- Class Two Summer Vacation AssignmentDocument1 pageClass Two Summer Vacation AssignmentshahbazjamPas encore d'évaluation

- Itc LimitedDocument64 pagesItc Limitedjulee G0% (1)

- How To Do Banana Milk - Google Search PDFDocument1 pageHow To Do Banana Milk - Google Search PDFyeetyourassouttamawayPas encore d'évaluation

- Pengaruh Kualitas Anc Dan Riwayat Morbiditas Maternal Terhadap Morbiditas Maternal Di Kabupaten SidoarjoDocument9 pagesPengaruh Kualitas Anc Dan Riwayat Morbiditas Maternal Terhadap Morbiditas Maternal Di Kabupaten Sidoarjohikmah899Pas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis ProposalDocument19 pagesThesis Proposaldharmi subedi75% (4)

- Null 6 PDFDocument1 pageNull 6 PDFSimbarashe ChikariPas encore d'évaluation

- Royal British College IncDocument5 pagesRoyal British College IncLester MojadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Valve Material SpecificationDocument397 pagesValve Material Specificationkaruna34680% (5)

- Benzil PDFDocument5 pagesBenzil PDFAijaz NawazPas encore d'évaluation

- Yogananda Scientific HealingDocument47 pagesYogananda Scientific HealingSagar Pandya100% (4)

- Parche CRP 65 - Ficha Técnica - en InglesDocument2 pagesParche CRP 65 - Ficha Técnica - en IngleserwinvillarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lichens - Naturally Scottish (Gilbert 2004) PDFDocument46 pagesLichens - Naturally Scottish (Gilbert 2004) PDF18Delta100% (1)

- A Project Report On A Study On Amul Taste of India: Vikash Degree College Sambalpur University, OdishaDocument32 pagesA Project Report On A Study On Amul Taste of India: Vikash Degree College Sambalpur University, OdishaSonu PradhanPas encore d'évaluation

- D6228 - 10Document8 pagesD6228 - 10POSSDPas encore d'évaluation

- Potato Storage and Processing Potato Storage and Processing: Lighting SolutionDocument4 pagesPotato Storage and Processing Potato Storage and Processing: Lighting SolutionSinisa SustavPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Report CMV RetinitisDocument27 pagesCase Report CMV RetinitistaniamaulaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Chemistry Xi: Short Questions and 20% Long QuestionsDocument3 pagesChemistry Xi: Short Questions and 20% Long QuestionsSyed Nabeel HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- Adsorbents and Adsorption Processes For Pollution ControlDocument30 pagesAdsorbents and Adsorption Processes For Pollution ControlJoao MinhoPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2 and 3 ImmunologyDocument16 pagesChapter 2 and 3 ImmunologyRevathyPas encore d'évaluation

- Method Statement (RC Slab)Document3 pagesMethod Statement (RC Slab)group2sd131486% (7)

- 6 Kuliah Liver CirrhosisDocument55 pages6 Kuliah Liver CirrhosisAnonymous vUEDx8100% (1)

- Xi 3 1Document1 pageXi 3 1Krishnan KozhumamPas encore d'évaluation

- ALL102-Walker Shirley-Unemployed at Last-The Monkeys Mask and The Poetics of Excision-Pp72-85Document15 pagesALL102-Walker Shirley-Unemployed at Last-The Monkeys Mask and The Poetics of Excision-Pp72-85PPas encore d'évaluation