Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal Lesbian

Transféré par

nsmhmCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Jurnal Lesbian

Transféré par

nsmhmDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

COUNSELING APPROACHES AND RELATED ISSUES IN SEXUAL RELATIONSHIPS

Rafidah Aga Mohd Jaladin

Abstrak

Secara khususnya artikel ini berfokus kepada hubungan homoseksual di kalangan wanita,

iaitu lesbianisme. Masalah golongan minoriti lesbian memang sukar difahami kerana lesbian

merupakan 'golongan yang tidak diiktiraf' di negara kita. Namun, untuk menjadi seorang

kaunselor yang berkesan, perlu ada persediaan diri dan kelayakan profesional yang

mencukupi untuk memberi khidmat kaunseling kepada mereka yang memerlukan.

Masalahnya tidak ramai yang tahu latar belakang kehidupan lesbian dan bentuk

permasalahan yang dihadapi oleh golongan ini. Kertas ini cuba memberi pendedahan tentang

kehidupan dan latar belakang lesbian di dalam masyarakat kita. Tumpuan utama akan

diberikan kepada pendekatan yang boleh digunapakai untuk memberikan khidmat kaunseling

kepada golongan lesbian. Isu yang berkaitan dengan etika dan nilai masyarakat dalam

membantu klien lesbian turut dibincangkan.

Introduction

In the Malaysian context, it is generally unknown how much people know about lesbianism

and to what extent they would accept the lesbians' existence and their unique lifestyle. It is

undeniable that an abundance of information about lesbianism exists on the internet, in

newspapers, magazines, films, novels, books, and other sources. However, we do not know

whether this information is meaningful to Malaysian people. Being in a Muslim majority

country with strong traditional values, most Malaysians tend to view lesbianism as a

disgraceful and shameful act. Malaysian society in general also rejects homosexuality.

The phenomenon of lesbianism can be detected if one truly pays attention to the "hidden"

issues normally discussed in newspapers or magazines. The most frequently sought-after

columns that lesbians use as a medium of expression are "Bisikan Rasa", "Nostalgia",

"Nukilan Rasa" and the like. Lesbianism has been known and practised secretly among a

minority of female students at boarding schools (especially at segregated schools), and

among artists, police and army officers, and even among professionals and intellectuals. How

to understand lesbianism in the Malaysian context and how to deal with the lesbian

community are the major concerns of people in the helping profession. It is also the focus of

this paper.

This paper is aimed at describing lesbianism with special focus on the various approaches for

counseling lesbian clients. Some ethical and value issues in counseling lesbian clients are

also discussed to help counselors and counselor trainees to be aware of, and predict, the

potential problems.

Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya 115

Definition and Female Sexual Identity Problems

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) classifies lesbians and

gays in Group A referring to sexual disorders due to sexual identity problems. According to

Dr. Mat Saat Bald (in Rozienah Husain, 1988), sexual identity disorders can be classified

into three different types: Transverse-Style, Transsexual, and Homosexual. Transverse-style

refers to women who like to dress and act like men but have no intention of changing their

sexual organs. This group of women is also sexually interested in men. They are also known

as heterosexuals or bisexuals or locally known as bapok, mak nyah or pondan (Mohd Tajudin

& Mohamed Mansor Abdullah, 2001). Transsexuals, on the other hand, are women who feel

like men and want to change their sexual organs in order to feel complete (Meriam Omar

Din, 2001). However, they may also be women who are very proud of acting and feeling like

men without a need to change their sexual organs (Rozienah Husain, 1988).

The homosexual type refers to women who have sexual relationships with other women.

They differ from the first two categories because they are only interested in women

(physically and sexually). They may act like ordinary women but their object of desire is

another woman. They accept themselves as women and do not want to be associated as men

(King & Bartlett, 1999). Lesbians fall under this category of gender identity disorder. An

interview with a registered counselor (Hushim Salleh, 2002) in Malaysia was conducted and

it was hypothesized that the roots of lesbianism are two-fold: (1) these women have gender

identity crisis and seem to not know themselves completely. They may know they are

females but they do not understand their sexual desires; and (2) they have gender disorder

because they are attracted to females only in terms of obtaining love, sexual satisfaction, and

in expressing their feelings.

Types of Female Homosexual

In Malaysia, there are six types of female homosexual behavior that counselors or counselor

trainees should be aware of (Rozienah Husain, 1988). These are:

1. Obvious lesbianism - refers to women who portray themselves as lesbians without

shame, worry, or fear; in fact, they are proud of their lesbian lifestyle.

2. Addicted lesbianism - refers to women who are in great need of finding another

woman to sleep with.

3. Secretive lesbianism - refers to women who secretly practise lesbian actrvitres.

Sometimes, married lesbian women carry out lesbian activities without their

husbands' knowledge. Only those very close to the women know about their hidden

agenda.

4. Adaptive lesbianism - refers to women who accept themselves as lesbians and live

like lesbians and who can easily adjust themselves to their environment.

116 Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya

5. Seasonal lesbianism - refers to women who seek female partners while at college or

when there are no men around. About 10% of them will remain as lesbians after

school or college life, and about 90% will behave like ordinary women and have

relationships with men.

6. Prostitute lesbianism - refers to women who have sex with other women as a means

of getting money. This is the type of lesbian that can be bought when needed.

Lesbian Lifestyle

Lesbian couples behave like spouses in a house, but they behave like normal women outside.

In Malaysia, the lesbian lifestyle is very difficult to detect compared to gays' because lesbians

are perceived as normal women living together as housemates and their relationship, even

though sexual in nature, is perceived as best friends. Lesbians in the relationship have their

own social roles. One will take the "masculine" role and the other will take the "feminine"

role. Sex roles are played accordingly and interchangeably. Their sexual relationship does not

involve usage of artificial penis or other sexual gadgets because most lesbians confess that

orgasm with female partners is much more satisfying than with male partners (Rozienah

Husain, 1988).

Lesbians' lives are established by their stance and this can be classified into two types: ego-

syntonic or ego-dystonic lesbianism. The ego-syntonic lesbian feels comfortable with her life

as a lesbian; she does not worry about being lesbian and happily accepts herself and enjoys

her life as a lesbian. On the other hand, the ego-dystonic lesbian is sexually attracted to

another woman but at the same time feels guilty about it. Due to this guilt, she views herself

as abnormal and is always in a state of fear. She feels forced to act and behave like a lesbian

because of her sexual instinct. Most lesbian clients in Malaysia have the egodystonic stance.

Contributing Factors in Lesbianism

According to Mat Saat Baki (Rozienah Husain, 1988) and other experts in the area (Meriam

Omar Din, 2001; Noriah Ishak, 2001), there are five factors that contribute to lesbianism.

First is the woman's childhood experience. A child's first contact and interaction is with

parents, and this relationship will determine the child's identity and social interaction in later

years. If parents encourage the child (intentionally or unintentionally) to behave

inconsistently with her gender, for example cross-dressing, the child might use this

experience to guide her future actions.

Second is the woman's sexual experience (Diamant, 1999). Those women who have had

experience of sex with both male and female can develop a personal preference for the better

partner. If the woman found her female partner more sexually satisfying, she may no longer

want to have sex with a man. Sometimes this applies to the woman's first sexual experience.

If the first was with a female partner, then there is a possibility that it will continue. Or if the

first was with a man and it was a bad experience, the woman might tum to another woman

for sex.

Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya 117

Third is the woman's hormonal regulation. Some women have less female hormones (e.g.

estrogen) but more male hormones (testosterone) and this causes the female to act like a man.

Fourth is the experimental experience of the woman, for example, if a woman experimented

having same-sex sexual experience, and she liked it a lot, she might continue doing it.

The last factor is the woman's traumatic experience during childhood or adolescence. If a

woman was raped by her father, brother or other male family member, she may generalize

her hatred and hate not only them but the rest of the male population. Counselors or other

professionals should be cautioned that if a woman experiences any of the abovementioned

factors, it means that she has an inclination towards lesbianism. However, she cannot be

labeled as a lesbian until the woman admitted it herself (Mat Saat Baki in Rozienah Husain,

1988).

Other contributory factors, according to Hushim Salleh (2002), are early exposure to

socialization (coming from a female dominated family or attending girls' boarding schools),

and influence of parenting style (e.g. having autocratic parents who restrict their daughters'

socialization with male friends).

Counseling Lesbian Clients from Several Approaches

In the Malaysian Counseling Association (PERKAMA) 10th Convention held on 12-13 May

2001 at the Academy of Islamic Studies, University of Malaya, Malaysian counselors and

psychiatrists presented several approaches in counseling clients with sexual identity problems

such as lesbians. The convention theme was "Managing Gender Identity Problems:

Collective Responsibility". Four approaches are relevant to the topic of interest: the

traditional approach; the non-traditional approach; object-relation therapy; and the Islamic

approach. The following section shall discuss the gist of these approaches.

The Traditional Approach

Psychiatrists normally use this approach because it is heavily based on the medical model

where symptoms are the main indicators of the client's problem. The main reference in

counseling a lesbian client is the DSM-IV because this manual classifies all the symptoms a

client may portray into five axes: Axis I (clinical disorders or other conditions that may be a

focus of clinical attention), Axis II (personality disorders or mental retardation), Axis III

(general medical conditions), Axis IV (psychosocial and environmental problems), and Axis

V (global assessment of functioning). Each axis explains the type of disorder or mental

illness experienced by patients or clients in the hospital or counseling setting (Mohd Tajudin

& Mohamed Mansor, 2001). Lesbians and gays fall under the category of gender identity

disorder.

118 Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya

The Non-traditional Approach

Counselors and psychologists who use the DSM-IV manual as reference normally use this

approach. They use the manual as reference in addition to the humanistic approach in their

counseling process (Mohd Tajudin & Mohamed Mansor, 2001). This is different from the

traditional approach used by most psychiatrists because the non-traditional approach does not

totally rely on the manual to identify the client's problem. The non-traditional approach

discusses the client's case based on the following five factors:

a. life stage developmental approach;

b. cross-cultural approach;

c. gender role analysis;

d. ecological analysis, and

e. trauma analysis

Mohd Tajudin and Mohamed Mansor (2001) suggested that all these factors can give holistic

information on the nature of the client's problem.

Hushim Salleh (2002) reported that lesbian clients he helped had problems with their sexual

orientation. Thus, the counseling process will start with rapport in order to establish truce

before focusing on the exploration stage. This exploration stage is crucial because the clients

will disclose their history: when, where, how and why they were involved in lesbianism.

Then comes the problem identification stage, followed by generation of alternatives. In the

next stage, both counselor and client would discuss the pros and cons of each alternative so

that the client can take appropriate action. If the problems are based on the client's sexual

orientation, then the best theory to use is Rational Emotive Theory (Hushim Salleh, 2002).

However, Meriam Omar Din (2001) suggested a typical Person-Centered Counseling (PCC),

founded by Rogers. This approach has five requirements: (1) accepting and being accepted;

(2) building the clients' trust; (3) encouraging clients to share their subjective experience; (4)

detecting clients' awareness in terms of the changes that happened to them. The changes are

observed in terms of their coping mechanism, physical appearance, beliefs, thoughts, locus of

evaluation, and communication skills. If counselors are aware of these small changes, they

can encourage and help the lesbian clients to make bigger changes in their lives. The final

stage would be (5) helping clients to tackle "here-and-now" problems in a continuous manner

so that they understand the actual problem. Counselors can thus prevent clients from

committing further self-destructive behaviors that invite permanent consequences.

Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya 119

Object-Relation Therapy

Object-relation therapy differs from other therapies in terms of understanding the clients'

issues and problems. It takes into account the self, the significant others, and how these two

interact. This interaction brings a unique meaning to the person experiencing it and can only

be explained by the person. Thus, an object-relation therapist must focus on the theme of the

story presented by clients in the counseling session because this theme has its own unique

meaning from the clients' perspective. Specifically, this approach is used to explore the

clients' internal psychological process that refers to their life meanings. The therapy assumes

that each meaning assigned to life episodes is due to the individual's interaction with others.

This interaction influences and shapes her external and internal life. The therapy also

assumes that the individual's meaning of life indicates the individual herself.

The therapy uses specific concepts such as the third reality (referring to the client-counselor

relationship), working models (referring to an individual's cognitive schema), attachment

(referring to early childhood attachment and adult attachment), and holding environment

(referring to the way the counselor should treat the client, i.e. "seperti menatang minyak yang

penuh" (Noriah Ishak, 2001, p.IOl). The counseling process has three stages: initial, middle

and final therapy. The initial therapy focuses on creating a conducive environment, building

trust, understanding, and learning about the client. The middle therapy is about helping the

client gradually see, tolerate, understand, challenge, and then reconstruct and change old

meanings about oneself to others, and oneself to herself. The final therapy is where the

counselor encourages the client to understand the new internal working model and to use the

model as a guide to change. Sometimes, the counselor may say "it is okay to be the new you,

while remembering the old self' (Noriah Ishak, 2001, p. 11).

The Islamic Perspective

Islam does not allow lesbianism in Muslim society because "Allah the Almighty condemns

those men who appear like women and those women who appear like men" (Asmungi Sidek,

2001, p.?). Thus, counseling a lesbian client using the Islamic perspective may cause some

difficulties because of the conflict between Islamic teachings and lesbianism. However, if the

lesbian client would like to change her sexual orientation because of guilt feelings, this

approach may be of help because the goal of the client and the counseling process would

coincide.

Norazman Amat (2001) presented 11 steps of the Islamic counseling process as guidelines

for Muslim counselors: (1) set proper goal, (2) say prayers to Allah, (3) establish therapeutic

counseling relationship with client, (4) assist the client in exploring herself, (5) express

understanding and empathy, (6) guide the client's exploration and help her to understand, (7)

identify the client's needs, (8) help the client to set goals, explore alternatives, and plan

strategy, (9) encourage the client to act and bertawakkal (have absolute trust in Allah), (10)

help the client to gain insight into her problem, and (11) end the counseling process once the

client is ready to act and change.

120 Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya

Ethical and Value Issues in Counseling Lesbian Clients

Lesbians are a minority group and working with them is challenging especially to those with

restrictive attitudes and values towards homosexuals (Peterson, 1970). Counselors who have

negative reactions to homosexuals have to be careful not to impose their own values on their

clients because they are bound by ethical and moral obligations. The ethical codes of the

American Counseling Association (ACA), the American Psychological Association (APA),

and the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) clearly state that discrimination on

the basis of minority status - be it race, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation - is unethical

and unacceptable (Corey et al., 1998). Thus, counselors need to have sufficient knowledge

and skills to provide sensitive treatment to lesbians.

Corey et al. (1998) commented, "Unless counselors become conscious of their own faulty

assumptions and homophobia, they may project their misconceptions and their fears onto

their clients. Therapists must confront their personal prejudices, myths, fears, and stereotypes

regarding sexual orientation" (p.lOO). In addition, Weinstein and Rosen (1988) contended

that when a person comes in for counseling and states that she is a "homosexual", it is

important to explore and understand what is meant by that declaration. Is the client

expressing a feeling? Is the declaration based on experiential factors? Is it based on fear? All

are possible because lesbians have had different life experiences. Counselors should not take

such labels at face value and at the same time should not negate their possible validity.

Besides ethical issues, value issues also arise in counseling lesbians. A number of special

situations are likely to produce "a crisis" or need for counseling (Weinstein & Rosen, 1988),

for example, facing discrimination, prejudice, and oppression in a society, workforce or

relationship. Weinstein and Rosen (1988) identified four special situations in counseling

lesbians. The first involves the decision to "come out". In most cases, lesbians often bring to

counseling the struggle between concealing their identity and "coming out" (Taylor, 1999).

Coming out refers to sharing one's identity with others such as parents, friends, spouse,

children, employer or anyone. Secondly, the confidentiality in dealing explicitly with the

clients may cause some problems because laws in the various states differ with respect to the

confidentiality of professional records. Thirdly, the problems of loneliness and grief are

common among lesbians. Lesbians are known for their desire for a long-term relationship

and sometimes this ends up in anguish over the dissolution of a relationship. These problems

are not unique to homosexuals, but they are exacerbated by the lack of societal support.

Lastly, lesbians may have problems with sex-related diseases such as AIDS and genital

human papillomavirus infection in women who have sex with women (Marrazzo, 2000).

With the reality of these diseases, lesbians often face the loss of friends or partners, the lack

of support for grieving, and also the fear of infection.

Counseling lesbian clients may become more challenging when it involves value conflict

between religion and homosexuality issues. Corey et al. (1998) cautioned all counselors to be

aware of the conflict between religion and homosexuality because it may pose problems for

both clients and counselors. A client's religious values can be a source of conflict to a person

who is struggling with sexual identity issues. At the same time, the religious and

Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya 121

moral values of counselors can also pose problems in maintaining objectivity when working

with clients who want to explore their sexual feelings, attitudes, and behaviors. In view of

this conflict, many writers have voiced their concern: Is it ethical to counsel lesbian clients

without having received specialized training with this population?

Implications for Counselors

Researchers have given many recommendations to address the issues in counseling lesbian

clients. Most proposed quite similar strategies, such as to first critically examine any myths

and misconceptions they hold about lesbians, and then to obtain specialized training in

working with lesbian clients. Specifically, they proposed the following guidelines when

counseling lesbian clients: (1) to change counselors' attitudes toward lesbians; (2) to acquire

a body of knowledge about community resources for these clients; (3) to confront counselors'

personal prejudices, myths, fears, and stereotypes regarding sexual orientation (Weeks,

1985); (4) to acquire specialized knowledge about the lesbian population in general and

about the meaning of a lesbian identity to particular individuals (Schneider & Tremble,

1986); and (5) to continue educating themselves about lesbian identity development and

management (Eliason, 1996).

These guidelines are consistent with the goal of helping the lesbian client advocated by most

mental health professionals, that is, to accept her sexual orientation and to cope with the

possibility of stigmatization (Schneider & Tremble, 1986). Most experts in this field suggest

that counselors increase their awareness of ethical and therapeutic considerations in working

with lesbian clients by taking advantage of continuing education workshops sponsored by

national, regional, state, and local professional organizations (Corey et al., 1998; Weinstein

& Rosen, 1988; Schneider & Tremble, 1986). Studies have shown that workshops developed

to enhance expertise of service providers who work with lesbian clients are proven effective.

Their benefit is not just in helping lesbian clients but they also contribute to changing

society's stereotypes and prejudices toward this minority population so that lesbians get

societal support when needed.

Conclusion

To understand lesbianism in a society that prohibits the practice of lesbianism is not an easy

task because of the many value issues and conflicts a counselor has to consider. However,

there are ways to prepare ourselves for helping a lesbian client such as by fully understanding

the code of ethics, always consulting other experienced experts, and following the counseling

association guidelines. We cannot always be the best in helping others but we can always try

the best possible way to help them as long as we adhere to ethical guidelines.

122 Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya

References

Asmungi Haji Mohd Sidek (2001). Kecelaruan gender dan perspektif agama Islam.

Konvensyen PERKAMA ke 10: Kaunseling Kecelaruan Gender (12-13 Mei, 2001).

Persatuan Kaunseling Malaysia.

Corey, G., Corey, M.S., & Callanan, P. (1998). Issues and ethics in the helping professions

(5th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Diamant, A.L. (1999). Lesbians' sexual history with men: Implications for taking a sexual

history. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159 (22),2730-2736.

Eliason, M. J. (1996). Working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual people: Reducing negative

stereotypes via inservice education. Journal of Nursing Staff Development, 12 (3),

127-132.

King, M., & Bartlett, A. (1999). British psychiatry and homosexuality. The British Journal of

Psychiatry, 175 (8), 106-113.

Marrazzo, J. (2000). Genital human papillomavirus infection in women who have sex with

women: A review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 183 (3), 770774.

Mat Saat Baki (2001). Ujian psikometrik identifikasi kecelaruan gender. Konvensyen

PERKAMA ke 10: Kaunseling Kecelaruan Gender (12-13 Mei, 2001). Persatuan

Kaunseling Malaysia.

Meriam Omar Din (2001). Pendekatan dan proses kaunseling kecelaruan gender.

Konvensyen PERKAMA ke 10: Kaunseling Kecelaruan Gender (12-13 Mei, 2001).

Persatuan Kaunseling Malaysia.

Mohd Tajudin Haji Ninggal, & Mohamed Mansor Abdullah (2001). Terapi pengurusan

kecelaruan gender berasaskan DSM-IV: Satu diagnosis ringkas menggunakan

pendekatan "Non-Traditional". Konvensyen PERKAMA ke 10: Kaunseling

Kecelaruan Gender (12-13 Mei, 2001). Persatuan Kaunseling Malaysia.

Norazman Amat (2001). Pengurusan kecelaruan gender dari perspektif Islam. Konvensyen

PERKAMA ke 10: Kaunseling Kecelaruan Gender (12-13 Mei, 2001). Persatuan

Kaunseling Malaysia.

Noriah Mohd Ishak (2001). Terapi kecelaruan gender (Terapi "Object-Relation").

Konvensyen PERKAMA ke 10: Kaunseling Kecelaruan Gender (12-13 Mei, 2001).

Persatuan Kaunseling Malaysia.

Peterson, J.A. (1970). Counseling and values: A philosophical examination. Scranton, PA:

International Textbook Company.

Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya 123

Rozienah Husain (1988). Lesbianisme: Satu kajian perpustakaan. Kuala Lumpur: Jabatan

Penulisan Universiti Malaya.

Schneider, M.S., & Tremble, B. (1986). Training service providers to work with gay or lesbian

adolescents: A workshop. Journal of Counseling and Development, 65, 9899.

Taylor, B. (1999). 'Coming out' as a life transition: Homosexual identity formation and its

implications for health care practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30 (2), 520-525.

Weeks, J. (1985). Sexuality and its discontents: Meanings, myths, and modern sexualities.

New York: Routledge.

Weinstein, E., & Rosen, E. (1988). Sexuality counseling: Issues and implications. Pacific Grove,

CA: Brooks/Cole.

124 Masalah Pendidikan Jilid 26

Hakcipta@2003 Fakulti Pendidikan Universiti Malaya

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Comandos AsteriskDocument6 pagesComandos AsteriskWellington VagettiPas encore d'évaluation

- Bi Lives: Bisexual Women Tell Their StoriesD'EverandBi Lives: Bisexual Women Tell Their StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5)

- 212-Article Text-580-1-10-20200222Document30 pages212-Article Text-580-1-10-20200222ali nusPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Single Hood From The Experiences of Never-Married Malay Muslim Women in Malaysia - Some Preliminary FindingsDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Single Hood From The Experiences of Never-Married Malay Muslim Women in Malaysia - Some Preliminary FindingsFarizullah OthmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Elite Malay Polygamy: Wives, Wealth and Woes in MalaysiaD'EverandElite Malay Polygamy: Wives, Wealth and Woes in MalaysiaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Aspect of Commercial Aviation Do You Believe Has The Greatest Effect On The U.editedDocument6 pagesWhat Aspect of Commercial Aviation Do You Believe Has The Greatest Effect On The U.editedJohn JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation On HomosexualityDocument31 pagesPresentation On Homosexualityजब वी टॉकPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Lesbianism Perspectives in East AsiaDocument7 pages1 Lesbianism Perspectives in East AsiaRobert MariasiPas encore d'évaluation

- Freeing Sexuality: Psychologists, Consent Teachers, Polyamory Experts, and Sex Workers Speak OutD'EverandFreeing Sexuality: Psychologists, Consent Teachers, Polyamory Experts, and Sex Workers Speak OutPas encore d'évaluation

- 37.1.5.transgenderism - Chang Lee WeiDocument18 pages37.1.5.transgenderism - Chang Lee WeiNurFarah NadiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Trnsgenders Diserve Our Attention: ObjectivesDocument7 pagesWhy Trnsgenders Diserve Our Attention: ObjectivesjamsheerPas encore d'évaluation

- In Your View Are There Ways of Looking at Women That Ordinarily Are Not Seen As Sexist But That When Examined More Closely Turn Out To Be Sexist?Document2 pagesIn Your View Are There Ways of Looking at Women That Ordinarily Are Not Seen As Sexist But That When Examined More Closely Turn Out To Be Sexist?Zehra Abbas rizviPas encore d'évaluation

- Mak NyahDocument5 pagesMak NyahNazsPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesbianism Assignment KisiiDocument9 pagesLesbianism Assignment Kisiifrank kipkoechPas encore d'évaluation

- Irreversible Damage: A detailed summary of Abigail Shrier's book to read in less than 30 minutesD'EverandIrreversible Damage: A detailed summary of Abigail Shrier's book to read in less than 30 minutesÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Identical Treatment in the Machine of the Law, The Quest for Transgender Civil RightsD'EverandIdentical Treatment in the Machine of the Law, The Quest for Transgender Civil RightsÉvaluation : 1 sur 5 étoiles1/5 (2)

- LESSON5 TASK5 GEELEC4 SantosAllyanaMarie - ABPOLSCI2ADocument6 pagesLESSON5 TASK5 GEELEC4 SantosAllyanaMarie - ABPOLSCI2AAllyanaMarieSantosPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact: Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention of Sexual Misconduct: Case Studies in Sexual AbuseD'EverandImpact: Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention of Sexual Misconduct: Case Studies in Sexual AbusePas encore d'évaluation

- How to Protect Young People Against Sexual Abuse and Risky Sexual BehaviorsD'EverandHow to Protect Young People Against Sexual Abuse and Risky Sexual BehaviorsPas encore d'évaluation

- Transgressive Sex: Subversion and Control in Erotic EncountersD'EverandTransgressive Sex: Subversion and Control in Erotic EncountersPas encore d'évaluation

- The Transgender Guide: Understanding TranssexualismD'EverandThe Transgender Guide: Understanding TranssexualismÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Gender and Society Chapter 2Document36 pagesGender and Society Chapter 2Jasmine BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mid Pop CultureDocument2 pagesMid Pop CultureNurAstriani SPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 3Document20 pagesChapter 3Lanz Aron EstrellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gender & Class StudiesDocument7 pagesGender & Class StudiesRAGALATHA REDDYPas encore d'évaluation

- Uhaul LesbiansDocument4 pagesUhaul Lesbiansapi-254642177Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Between the Lines: A Lesbian Feminist Critique of Feminist Accounts of SexualityD'EverandReading Between the Lines: A Lesbian Feminist Critique of Feminist Accounts of SexualityPas encore d'évaluation

- Sexual Disorders PDFDocument31 pagesSexual Disorders PDFABHINAVPas encore d'évaluation

- On Psychoanalysis of Autism: How Our Mind Works In Social ImpairmentD'EverandOn Psychoanalysis of Autism: How Our Mind Works In Social ImpairmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Final ProjectDocument11 pagesFinal Projectapi-242728603Pas encore d'évaluation

- LGBT From HRM PrespectiveDocument12 pagesLGBT From HRM PrespectivehartiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact: Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention of Sexual Misconduct: Case Studies in Sexual AbuseD'EverandImpact: Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention of Sexual Misconduct: Case Studies in Sexual AbusePas encore d'évaluation

- Interview Lovendino Samantha Nicole A.Document6 pagesInterview Lovendino Samantha Nicole A.Ramirez Mark IreneaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Case Study of Jun JunDocument6 pagesThe Case Study of Jun JunAshley KatePas encore d'évaluation

- Feminist ManifestoDocument5 pagesFeminist Manifestomax quaylePas encore d'évaluation

- LGBTQDocument17 pagesLGBTQANAMIKA YADAV100% (1)

- Summary of Be a Revolution by Ijeoma Oluo: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooD'EverandSummary of Be a Revolution by Ijeoma Oluo: How Everyday People Are Fighting Oppression and Changing the World—and How You Can, TooPas encore d'évaluation

- ContractDocument2 pagesContractibanadavPas encore d'évaluation

- SogieDocument8 pagesSogieDeo Nuevo CollaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade 10 3rd Grading - Contemporary Issues - Student Hand Out (Compilation of Topics) Without Activity and InstructionDocument10 pagesGrade 10 3rd Grading - Contemporary Issues - Student Hand Out (Compilation of Topics) Without Activity and InstructionAhou Ania Qouma JejaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sex Guide For Women: The Roadmap From Sleepy Housewife to Energetic Woman Full of Sexual Desire: Sex and Relationship Books for Men and Women, #2D'EverandSex Guide For Women: The Roadmap From Sleepy Housewife to Energetic Woman Full of Sexual Desire: Sex and Relationship Books for Men and Women, #2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sex Guide For Women: The Roadmap From Sleepy Housewife to Energetic Woman Full of Sexual DesireD'EverandSex Guide For Women: The Roadmap From Sleepy Housewife to Energetic Woman Full of Sexual DesirePas encore d'évaluation

- Module 5Document4 pagesModule 5Arnel F. PradiaPas encore d'évaluation

- ICTSAS601 Student Assessment Tasks 2020Document30 pagesICTSAS601 Student Assessment Tasks 2020Lok SewaPas encore d'évaluation

- Assignment File - Group PresentationDocument13 pagesAssignment File - Group PresentationSAI NARASIMHULUPas encore d'évaluation

- Quiz 07Document15 pagesQuiz 07Ije Love100% (1)

- Describe The Forms of Agency CompensationDocument2 pagesDescribe The Forms of Agency CompensationFizza HassanPas encore d'évaluation

- FCAPSDocument5 pagesFCAPSPablo ParreñoPas encore d'évaluation

- Vickram Bahl & Anr. v. Siddhartha Bahl & Anr.: CS (OS) No. 78 of 2016 Casе AnalysisDocument17 pagesVickram Bahl & Anr. v. Siddhartha Bahl & Anr.: CS (OS) No. 78 of 2016 Casе AnalysisShabriPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Interior Architects in Kolkata PDF DownloadDocument1 pageBest Interior Architects in Kolkata PDF DownloadArsh KrishPas encore d'évaluation

- Type of MorphologyDocument22 pagesType of MorphologyIntan DwiPas encore d'évaluation

- Ob AssignmntDocument4 pagesOb AssignmntOwais AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract of Lease (711) - AguilarDocument7 pagesContract of Lease (711) - AguilarCoy Resurreccion Camarse100% (2)

- Taxation: Presented By: Gaurav Yadav Rishabh Sharma Sandeep SinghDocument32 pagesTaxation: Presented By: Gaurav Yadav Rishabh Sharma Sandeep SinghjurdaPas encore d'évaluation

- Advanced Financial Accounting and Reporting Accounting For PartnershipDocument6 pagesAdvanced Financial Accounting and Reporting Accounting For PartnershipMaria BeatricePas encore d'évaluation

- Haloperidol PDFDocument4 pagesHaloperidol PDFfatimahPas encore d'évaluation

- Precertification Worksheet: LEED v4.1 BD+C - PrecertificationDocument62 pagesPrecertification Worksheet: LEED v4.1 BD+C - PrecertificationLipi AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- A - Persuasive TextDocument15 pagesA - Persuasive TextMA. MERCELITA LABUYOPas encore d'évaluation

- Ict - chs9 Lesson 5 - Operating System (Os) ErrorsDocument8 pagesIct - chs9 Lesson 5 - Operating System (Os) ErrorsOmengMagcalasPas encore d'évaluation

- Lower Gastrointestinal BleedingDocument1 pageLower Gastrointestinal Bleedingmango91286Pas encore d'évaluation

- Photo Essay (Lyka)Document2 pagesPhoto Essay (Lyka)Lyka LadonPas encore d'évaluation

- Peter Honigh Indian Wine BookDocument14 pagesPeter Honigh Indian Wine BookVinay JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Dumont's Theory of Caste.Document4 pagesDumont's Theory of Caste.Vikram Viner50% (2)

- Pharmaniaga Paracetamol Tablet: What Is in This LeafletDocument2 pagesPharmaniaga Paracetamol Tablet: What Is in This LeafletWei HangPas encore d'évaluation

- A List of Run Commands For Wind - Sem AutorDocument6 pagesA List of Run Commands For Wind - Sem AutorJoão José SantosPas encore d'évaluation

- TIMELINE - Philippines of Rizal's TimesDocument46 pagesTIMELINE - Philippines of Rizal's TimesAntonio Delgado100% (1)

- Slides 99 Netslicing Georg Mayer 3gpp Network Slicing 04Document13 pagesSlides 99 Netslicing Georg Mayer 3gpp Network Slicing 04malli gaduPas encore d'évaluation

- Result 1st Entry Test Held On 22-08-2021Document476 pagesResult 1st Entry Test Held On 22-08-2021AsifRiazPas encore d'évaluation

- 1-Gaikindo Category Data Jandec2020Document2 pages1-Gaikindo Category Data Jandec2020Tanjung YanugrohoPas encore d'évaluation

- Seangio Vs ReyesDocument2 pagesSeangio Vs Reyespja_14Pas encore d'évaluation

- August 2023 Asylum ProcessingDocument14 pagesAugust 2023 Asylum ProcessingHenyiali RinconPas encore d'évaluation

- Psychology Research Literature Review ExampleDocument5 pagesPsychology Research Literature Review Exampleafdtsebxc100% (1)

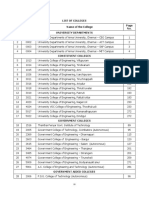

- TNEA Participating College - Cut Out 2017Document18 pagesTNEA Participating College - Cut Out 2017Ajith KumarPas encore d'évaluation