Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

MA22A Ejercicios Resueltos 5 1

Transféré par

Gonzalo JimenezDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

MA22A Ejercicios Resueltos 5 1

Transféré par

Gonzalo JimenezDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

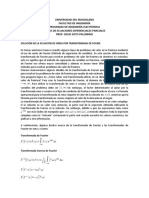

Facultad de Ciencias Fsicas y Matematicas U.

de Chile 17 de agosto de 2005

Ejercicios capitulo 5

Profesores: Rafael Correa, Pedro gajardo

auxiliares: Gonzalo S anchez, Rodolfo Gainza

P1) Sea E = C([0, 1], R) con la norma del supremo. calcul las derivadas direccionales , si es

que existen, de las siguientes funciones:

i)

I

g

: E R

f I

g

(f) =

1

0

g(x)f(x)dx

ii)

P

k

: E E

f P

k

(f) = f

k

iii)

EXP : E E

f EXP(f) = e

f

iv)

SEN : E E

f SEN(f) = sen o f

v)

COS : E E

f COS(f) = cos o f

P2) calcule el diferencial en un punto f E , si es que existe, de las siguientes funciones:

i) I

g

, ii) P

k

, iii) EXP, iv) SEN, v) COS.

P3) calcule el diferencial en un punto f E , si es que existe, de las siguientes funciones:

i) I

g

o P

k

ii) I

g

o SEN o EXP

iii) EXP o COS o P

k

iv) COS o SEN

v) I

g

o SEN o P

k

o EXP

P4) Dado el elipsoide en R

3

denido por x

2

+ y

2

+

z

2

2

= 1y el cambio de coordenadas

g((r, , )

t

) = (r cos() sen(), r cos() cos(), r sen())

t

calcular

dr

d

sobre cualquier pun-

to del elipsoide en el primer cuadrante.

P5) Sea

f : R

2

R

2

(r, ) f((r, )) = (x, y) = (r cos(), r sen())

1

i) demustre que f es localmente invertible entorno a cada punto de R

2

con r = 0.

ii) calcule el diferencial de la inversa entorno a cada punto de la circunferencia

x

2

+ y

2

= 0

P6) Sea f C

2

(R

4

, R) (f(x, y, z, t)) se dene el Laplaciano en coordenadas rectangulares

como:

f :=

d

2

f

dx

2

+

d

2

f

dy

2

+

d

2

f

dz

2

mostrar que el Laplaciano en coordenadas esfericas ( ver problema4) es:

e

f :=

1

r

2

d

dr

r

2

d

dr

f

+

1

r

2

cos()

d

d

cos()

d

d

f

+

1

r

2

cos

2

()

d

2

d

2

f

P7) Sea u = f(x, y) con el cambio de variables:x = r cos(), y = r sen() demuestre que:

du

dx

2

+

du

dy

2

=

du

dr

2

+

1

r

2

du

d

2

P8) Sea f : R

n

R diferenciable y sean G : R R y H : R

n

R denidas por:

G(t) = f(t, ..., t) y H(x

1

, ..., x

n

) = G(

x

1

+...+x

n

n

)

Calcular la derivada de G y el gradiente de H en terminos de las derivadas parciales

de f.

P9) Sea f positivamente homogenea (i.e. x E t > 0 f(tx) = tf(x))

Pruebe que si f es diferenciable en 0 entonces f es lineal.

2

Facultad de Ciencias Fsicas y Matematicas U. de Chile 21 de septiembre de 2005

Anexo capitulo 5 del apunte del curso MA22A a no 2005

Profesores: Rafael Correa, Pedro gajardo

auxiliares: Gonzalo S anchez, Rodolfo Gainza

P1) i)

DI

g

(f; d) = lm

t0

1

_

0

g(x) (f(x) + td(x))

1

_

0

g(x)f(x)

t

=

1

_

0

g(x)f(x) = I

g

(f)

ii)

DP

k

(f; d) = lm

t0

(f + td)

k

f

k

t

= lm

t0

k

i=o

k!

i!(ki!)

f

i

t

ki

d

ki

f

k

t

= lm

t0

k1

i=0

k!

i!(k i)!

f

i

t

ki1

d

ki

=

k1

i=0

k!

i!(k i)!

f

i

d

ki

lm

t0

t

ki1

= kf

k1

d

iii)

DEXP(f; d) = lm

t0

e

f+td

e

f

t

= lm

t0

e

f

e

td

1

t

= e

f

lm

t0

e

td

1

t

= e

f

d

esto se tiene pues: lm

h0

e

h

1h

h

= 0 en efecto la x (1, 1) se tiene que:

0 e

x

1 x

x

2

1x

con esto se tiene que :

0 e

h(x)

1 h(x)

h(x)

2

1 h(x)

si h < 1 entonces:

_

_

e

h

1 h

_

_

h

2

1 h

dividiendo por h 0 se obtiene el resultado pues :

lm

h0

h

1 h

= 0 y por lo tanto lm

t0

e

td

1

t

d = lm

t0

e

td

1 td

t

= 0

iv)

DSEN(f; d) = lm

t0

SEN(f + td) SEN(f)

t

= lm

t0

SEN(f)COS(td) + COS(f)SEN(td) SEN(f)

t

1

= lm

t0

SEN(f)

_

COS(td) 1

t

_

+ lm

t0

COS(f)

SEN(td)

t

= COS(f)d

pues: lm

t0

COS(td)1

t

= 0 y lm

t0

SEN(td)

t

= d pero probaremos el resultado mas general: lm

h0

COS(h)1

h

=

0 y lm

h0

SEN(h)h

h

= 0: Como el cos es una funcion diferenciable en R se tiene que para x

cercano a 0 : cos(x) 1 = o(x).

Por lo tanto si h es lo sucientemente cercana a 0 se tendra: cos(h(x)) 1 = o(h(x)) tomando

norma en esta igualdad y ya que o(h) = o(h) obtenemos que :

COS(h) 1 = o(h) y por lo tanto lm

h0

COS(h) 1

h

= 0

Analogamente, usando tailor de orden 2 entorno a 0, se tendra :SEN(h) h = o(h) y por lo

tanto:

lm

h0

SEN(h) h

h

= 0

nalmente para obtener los limites deseados basta remplazar h por td y usar que td = |t| d .

v)

DCOS(f; d) = lm

t0

COS(f + td) COS(f)

t

lm

t0

COS(f)COS(td) SEN(f)SEN(td) COS(f)

t

= lm

t0

COS(f)

COS(td) 1

t

+ lm

t0

SEN(f)

SEN(td)

t

= SEN(f)d

NOTAS: en este problema se ha usado que si f

n

F y h

n

H en E entonces

lm

n

f

n

h

n

= FH y que: fg

.

P2) i) Como I

g

es lineal continua se tiene que f E DI

g

(f) = I

g

.

ii)

_

_

P

k

(f + h) P

k

(f) kf

k1

h

_

_

=

_

_

_

_

_

k

i=0

k!

i!(k i)!

f

i

h

ki

f

k

kf

k1

h

_

_

_

_

_

=

_

_

_

_

_

k2

i=0

k!

i!(k i)!

f

i

h

ki

_

_

_

_

_

k2

i=0

f

i

h

ki

=

_

k2

i=0

f

i

h

ki2

_

h

2

cte(f, k) h

2

= o(h)

iii)

lm

h0

EXP(f + h) EXP(f) EXP(f)h

h

= lm

h0

_

_

e

f

_

e

h

1 h

__

_

h

lm

h0

_

_

e

f

_

_

_

_

e

h

1 h

_

_

h

=

_

_

e

h

_

_

lm

h0

_

_

e

h

1 h

_

_

h

= 0

2

iv)

lm

h0

SEN(f + h) SEN(f) COS(f)h

h

= lm

h0

SEN(f)COS(h) + SEN(h)COS(f) SEN(f) COS(f)h

h

lm

h0

SEN(f) (COS(h) 1)

h

+ lm

h0

COS(f) (SEN(h) h)

h

SEN(f) lm

h0

COS(h) 1

h

+ COS(f) lm

h0

SEN(h) h

h

= 0

v)

lm

h0

COS(f + h) COS(f) + SEN(f)h

h

= lm

h0

COS(f)COS(h) SEN(f)SEN(h) COS(f) + SEN(f)h

h

lm

h0

COS(f) (COS(h) 1)

h

+ lm

h0

SEN(f) (h SEN(h))

h

COS(f) lm

h0

COS(h) 1

h

+ SEN(f) lm

h0

h SEN(h)

h

= 0

P3 La existencia se asegura por el problema 2 por lo que solo se debe utilizar la regla de la cadena.

i) D[I

g

o P

k

](f)(h) = [(DI

g

(P

k

(f)) o DP

k

(f))](h) =

1

_

0

g(x)kf

k1

(x)h(x)dx

ii) D[I

g

o SEN o EXP](f)(h) = [DI

g

(SEN(EXP(f))) o DSEN(EXP(f)) o DEXP(f)](h)

=

1

_

0

g(x)COS(e

f(x)

)e

f(x)

h(x)dx

iii) D[EXP o COS o P

k

](f)(h) = [DEXP(COS(P

k

(f))) o DCOS(P

k

(f)) o DP

k

(f)](h)

= kEXP(COS(f

k

))SEN(f

k

)f

k1

h

iv) D[COS o SEN](f)(h) = [DCOS(SEN(f)) o DSEN(f)](h) = SEN(SEN(f))COS(f)h

v) D[I

g

o SEN o P

k

o EXP](f)(h)

= [DI

g

(SEN(P

k

(EXP(f)))) o DSEN(P

k

(EXP(f))) o DP

k

(EXP(f)) o DEXP(f)](h)

=

1

_

0

g(x)COS(e

kf(x)

)ke

(k1)f(x)

e

f(x)

h(x)dx

P4 Como x

2

+ y

2

+

z

2

2

= 1 entonces se tendra con en cambio de variables que:

1 = r

2

cos

2

() sin

2

() + r

2

cos

2

() cos

2

() +

r

2

sin

2

()

2

= r

2

cos

2

() +

r

2

sin

2

()

2

Se tiene entonces que r

2

=

2

2cos

2

()+sin

2

()

asi derivando implicitamente en una variable:

2r

r =

4 cos() sin()

(cos

2

()+1)

2

= r

2

cos() sin()

lo que implica que:

r = r

cos() sin()

2

=

r

4

sin(2)

3

P5 i) Tenemos f

1

(r, ) = (x, y) = r cos() y f

2

(r, ) = r sin() y :

Jf(r, ) =

_

r

f

1

f

1

r

f

2

f

2

_

=

_

cos() r sin()

sin() r cos()

_

Para que sea invertible su determinante debe ser no nulo y esto es :

_

cos() r sin()

sin() r cos()

_

= r(cos

2

() + sin

2

()) = r = 0

ii) Para calcular el diferencial de la inversa es necesario usar el teorema de la funcion inversa que

asegura que:

Df

1

(y) = Df(x)

1

donde y = f(x).

_

cos() sin()

sin() cos()

_

1

=

_

cos((arctan(

y

x

))) sin((arctan(

y

x

)))

sin((arctan(

y

x

))) cos((arctan(

y

x

)))

_

=

_

x y

y x

_

P6 Primero notemos que :

r

x = cos() sin() ;

r

y = cos() sin() ;

r

z = sin()

r

2

(

r

x)

2

= x

2

; r

2

(

r

y)(

r

x) = xy ; r

2

(

r

x)(

r

z) = xz

r

2

(

r

y)

2

= y

2

; r

2

(

r

y)(

r

x) = xy ; r

2

(

r

y)(

r

z) = yz

r

2

(

r

z)

2

= z

2

; r

2

(

r

y)(

r

z) = zy ; r

2

(

r

x)(

r

z) = xz

x = r sin() sin() ;

y = r sin() cos() ;

z = r cos()

x = x ;

2

y = y ;

2

z = z ; (

x)

2

= y

2

; (

y)

2

= x

2

; (

z)

2

= x

2

+ y

2

x = r cos() cos() ;

y = r cos() sin() ;

z = 0 ;

2

x = x ;

y = y ; (

x)(

y) = xy ; (

x)

2

= y

2

; (

y)

2

== x

2

Con estas identicaciones se puede proceder a derivar la funcion f:

r

f =

x

f

r

x +

y

f

r

y +

z

f

r

z y procedemos a calcular

r

(r

2

x

f

r

x) (las demas son analogas):

r

(r

2

x

f

r

x) = 2r

x

f

r

x + r

2

r

(

x

f)

r

x + {r

2

2

rr

x

x

f = 0}

r

(r

2

x

f

r

x) = 2r

x

f

r

x + r

2

_

2

xx

f(

r

x)

2

+

2

xy

f(

r

x)(

r

y) +

2

zx

f(

r

x)(

r

z)

_

r

(r

2

x

f

r

x) = x

_

2

x

f + x

2

xx

f + y

2

yx

f + z

2

zx

f

_

y analogamente:

r

(r

2

y

f

r

y) = y

_

2

y

f + y

2

yy

f + x

2

xy

f + z

2

zy

f

_

r

(r

2

z

f

r

z) = z

_

2

z

f + z

2

zz

f + y

2

yz

f + x

2

zx

f

_

y sumando:

r

(r

2

r

f) = 2 {x

x

f + y

y

f + z

z

f}+2

_

xy

2

xy

f + xz

2

xz

f + yz

2

yz

f

_

+

_

x

2

2

xx

f + y

2

2

yy

f + z

2

2

zz

f

_

Ahora veamos las derivadas con respecto a :

1

cos()

(cos()

f) =

1

cos()

[

(

x

f

x +

y

f

y +

z

f

z)]

=

1

cos()

{sin()[

x

f

x +

y

f

y +

z

f

z] + cos()[

2

x

x

f +

2

y

y

f +

2

z

z

f]

+cos()[

2

xx

f(

x)

2

+

2

yy

f(

y)

2

+

2

zz

f(

z)

2

+ 2

2

xy

f

y + 2

2

xz

f

z + 2

2

yz

f

z]}

=

sin()

cos()

[

x

f

x +

y

f

y +

z

f

z] [x

x

f + y

y

f + z

z

f]

+[

2

xx

f(

x)

2

+

2

yy

f(

y)

2

+

2

zz

f(

z)

2

] + 2[

2

xy

f

y +

2

xz

f

z +

2

yz

f

z]

1

cos

2

()

f =

1

cos

2

()

[

z

z

f +

z

z

f +

z

z

f}]

=

1

cos

2

()

{[

2

x

x

f +

2

y

y

f + (

x)

2

2

xx

f + (

y)

2

y

f + 2

y

2

xy

f]}

=

1

cos

2

()

[x

x

f + y

y

f] +

1

cos()

[(

x)

2

2

xx

f + (

y)

2

y

f + 2

y

2

xy

f]

y nalmente procedemos a agrupar terminos semejantes:

x

f{2x

sin()

cos()

x x

x

cos

2

()

} = 0

4

y

f{2y

sin()

cos()

y y

y

cos

2

()

} = 0

z

f{2z

sin()

cos()

z z} = 0

2

xy

f{2xy + 2

y +

2

cos

2

()

y} = 0

2

xz

f{2xz + 2

z} = 0

2

yz

f{2yz + 2

z} = 0

2

xx

f{x

2

+ (

x)

2

+

(

x)

2

cos

2

()

} =

2

xx

f

2

yy

f{y

2

+ (

y)

2

+

(

y)

2

cos

2

()

} =

2

yy

f

2

zz

f{z

2

+ (

z)

2

} =

2

zz

f

Lo que termina la demostracion.

P7 calculemos las derivadas de u conrespecto a las coordenadas circulares:

r

u =

x

u

r

x +

y

u

r

y

=

x

ucos() +

y

usin()

(

)u =

x

u

x +

y

u

y

=

x

u(r sin()) +

y

u(r cos())

= r{

x

usin() +

y

ucos()}

(

r

u)

2

= (

x

u)

2

cos

2

() + (

y

u)

2

sin

2

() + 2(

x

u)(

y

x) cos() sin()

+ +

1

r

2

(

u)

2

=

r

2

r

2

{(

x

u)

2

sin

2

() + (

y

u)

2

cos

2

() 2(

x

u)(

y

x) cos() sin()}

(

r

u)

2

+

1

r

2

(

u)

2

= (

x

u)

2

+ (

y

u)

2

P8 sea

I = (1, ..., 1)

t

(el vector de n unos) y sea g(t) = t

I y ,pm(x) =

1

n

x,

I =

1

n

n

i=1

x

i

entonces tenemos:

G = f o g y

H = G o pm

y notemos que tanto g como prom son lineales , y por ser R

n

de dimension nita continuas, entonces

por regla de la cadena se tendra:

G

(t) := DG(t)(1) = Df(g(t))oDg(t)(1) = f(g(t)), g(1) =

n

i=1

x

i

f(t

I)

x

j

H(x) := DH(x)( e

j

) = DG(pm(x))oDpm(x)(e

j

) = G

(pm(x))

x

j

pm(x) =

n

i=1

x

i

f(pm(x)

I)

1

n

P9 Para probar que f es lineal probaremos que f es igual a su diferencial en 0. En primer lugar dado que f

es diferenciable en 0 en particular es continua en 0 y por lo tanto:

f(0) = lm

n0

f(

1

n

x) = lm

n0

1

n

f(x) = 0

Ademas como es diferenciable en 0 se tendra que:

lm

h0

f(h)f(0)Df(0)(h)

h

= lm

h0

f(h)Df(0)(h)

h

= 0

Con esto probemos que

h E tq

_

_

_

h

_

_

_ = 1 se tiene:

f(

h) = Df(0)(

h)

En efecto sea > 0, entonces > 0 tal que, 0 < < se cumple:

5

f(

h)Df(0)(

h)

h

<

f(

h)Df(0)(

h)

<

_

_

_

1

f(

h)

1

Df(0)(

h)

_

_

_ <

_

_

_f(

h) Df(0)(

h)

_

_

_ < > 0

Lo cual implica que: f(

h) = Df(0)(

h) para todo

h unitario.

Ahora tomemos

h E entonces

h

h

es unitario y se tendra:

f

_

h

h

_

= Df(0)

_

h

h

_

1

h

f(

h) =

1

h

Df(0)(

h)

f(

h) = Df(0)(

h)

y nalmente: f(0) = 0 = Df(0)(0)

1

1

Hecho por Gonzalo Sanchez

6

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Sesion 3Document15 pagesSesion 3ErickRojasPas encore d'évaluation

- Caa Control 1Document51 pagesCaa Control 1Matías E. PhilippPas encore d'évaluation

- Guia I CalculoDocument3 pagesGuia I CalculoAimara LobosPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo de ResiduosDocument14 pagesCalculo de ResiduosAMYNNXXXXPas encore d'évaluation

- Universidad de Concepci On Facultad de Ciencias F Isicas y Matem Aticas Departamento de Matem AticaDocument2 pagesUniversidad de Concepci On Facultad de Ciencias F Isicas y Matem Aticas Departamento de Matem AticaMarco Cuevas SepulvedaPas encore d'évaluation

- DiferencialesDocument4 pagesDiferencialesAraceli ValenzuelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Taller Cal-Int (C) PDFDocument43 pagesTaller Cal-Int (C) PDFJorge Andres Hernandez GaleanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo Dif de VariaDocument11 pagesCalculo Dif de Variasickoff22Pas encore d'évaluation

- DerivadasDocument9 pagesDerivadasMeliandPas encore d'évaluation

- Taller de Derivadas Trabajo FinalDocument25 pagesTaller de Derivadas Trabajo FinalJulian RiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- Examen Parcial - FIEEDocument7 pagesExamen Parcial - FIEEKatherine Guadalupe Poma BalvínPas encore d'évaluation

- 13 Plano Tangente y Diferenciales ApunteDocument8 pages13 Plano Tangente y Diferenciales ApunteguillermocochaPas encore d'évaluation

- Solucionario PC 2 2021-IDocument4 pagesSolucionario PC 2 2021-Ibleachcs23Pas encore d'évaluation

- Resumen de Analisis 2Document12 pagesResumen de Analisis 2Gimena CabreraPas encore d'évaluation

- Fórmulario Cálculo Avanzado PEP2 2.0Document6 pagesFórmulario Cálculo Avanzado PEP2 2.0Francisco Javier Valenzuela RiquelmePas encore d'évaluation

- Trabajo2 2017Document5 pagesTrabajo2 2017Alvaro ChicoPas encore d'évaluation

- Regla de La CadenaDocument2 pagesRegla de La CadenaEduardo GonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Ecuaciones Diferenciales Parciales - Jube PortalatinoDocument40 pagesEcuaciones Diferenciales Parciales - Jube PortalatinoJunior Emerson Sanchez MendezPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo Vectorial Extremos de FuncionesDocument26 pagesCalculo Vectorial Extremos de FuncionesCésar PilarPas encore d'évaluation

- Exercicios Resolvidos - Transformada de LaplaceDocument35 pagesExercicios Resolvidos - Transformada de LaplaceDaianeLancPas encore d'évaluation

- Series de Fourier PDFDocument13 pagesSeries de Fourier PDFVíctor BurgosPas encore d'évaluation

- Trabajo 735Document15 pagesTrabajo 735EscorciaRoniPas encore d'évaluation

- Derivadas Calculo1 Guia3aDocument20 pagesDerivadas Calculo1 Guia3aWilmar Asdrubal Ayala MoralesPas encore d'évaluation

- Ejercicios DerivadasDocument8 pagesEjercicios DerivadasAntoine Dumont NeiraPas encore d'évaluation

- La DerivadaDocument11 pagesLa DerivadaMarcelo AlbaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo Diferencial e IntegralDocument10 pagesCalculo Diferencial e IntegralRyder Vladimir EricksonPas encore d'évaluation

- Derivadas ParcialesDocument9 pagesDerivadas ParcialesÁngel Varón CalderónPas encore d'évaluation

- Resumen de Análisis Matemático IIDocument29 pagesResumen de Análisis Matemático IIMaximiliano Alfaro100% (2)

- Exam03ago2017libre 1 2017-08-22-832Document2 pagesExam03ago2017libre 1 2017-08-22-832Franco VillarrealPas encore d'évaluation

- Series FourierDocument41 pagesSeries FourierEdwin RodriguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo IDocument53 pagesCalculo IAnthonyCondeMuñozPas encore d'évaluation

- Talleres Cal Integral3Document25 pagesTalleres Cal Integral3Andres Felipe Medina EaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Talleres Cal-Integral-2Document43 pagesTalleres Cal-Integral-2Julian FernandoPas encore d'évaluation

- Talleres Cal IntegralDocument16 pagesTalleres Cal IntegralShamash RamírezPas encore d'évaluation

- Solución de La Ecuación de Onda Por Transformada de FourieDocument6 pagesSolución de La Ecuación de Onda Por Transformada de FourieWilder CanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Max y MinDocument12 pagesMax y MinGustavo OrozcoPas encore d'évaluation

- Victor Pato Matematica Avanzada (Derivacion) (Iugt)Document9 pagesVictor Pato Matematica Avanzada (Derivacion) (Iugt)Francisco QuilarquePas encore d'évaluation

- Guia 3 Calculo 30Document7 pagesGuia 3 Calculo 30agua0% (1)

- Funciones Con Valores VectorialesDocument9 pagesFunciones Con Valores VectorialesVan de KampPas encore d'évaluation

- 2do. Examen de Matematica IV 735Document3 pages2do. Examen de Matematica IV 735hectorguevara1993Pas encore d'évaluation

- Taller 3 Segundo CorteDocument10 pagesTaller 3 Segundo CorteANDRES CAMEROPas encore d'évaluation

- Taller 10Document2 pagesTaller 10Luz CaicedoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cic 1Document4 pagesCic 1Saul PereiraPas encore d'évaluation

- Taylor y MaclaurinDocument8 pagesTaylor y MaclaurinGustavo D. CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- 735 - 16.996.517 - 2024-1 TSP1 - Jose BastardoDocument12 pages735 - 16.996.517 - 2024-1 TSP1 - Jose Bastardojose bastardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Formulario de Analisis MatematicoDocument14 pagesFormulario de Analisis Matematico1MONOGRAFIASPas encore d'évaluation

- Práctica 11 CálculoDocument4 pagesPráctica 11 CálculoGus Son of HadesPas encore d'évaluation

- GRADIENTEDocument5 pagesGRADIENTEJacqueline Britto EscarragaPas encore d'évaluation

- M - Clase 13 (Derivadas)Document27 pagesM - Clase 13 (Derivadas)Joaquin Alcantara De la TorrePas encore d'évaluation

- Monografía de DerivadasDocument98 pagesMonografía de DerivadasElvis Jenner Quintana VasquezPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo Diferencial Problemas ResueltosDocument12 pagesCalculo Diferencial Problemas ResueltosAlex SeanPas encore d'évaluation

- La DerivadaDocument12 pagesLa DerivadaAmIn20122Pas encore d'évaluation

- TP5 Regla de La CadenaDocument2 pagesTP5 Regla de La CadenaCinthia MolloPas encore d'évaluation

- Formulario de Cálculo VectorialDocument7 pagesFormulario de Cálculo VectorialAlonso Curiel Lopez100% (2)

- Calculo 3 PDFDocument8 pagesCalculo 3 PDFEstefany GomezPas encore d'évaluation

- 6.taller DerivadasDocument4 pages6.taller DerivadasANTONI avilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Teoría de cuerpos y teoría de GaloisD'EverandTeoría de cuerpos y teoría de GaloisÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Canaza Ecuas 2020 1P PDFDocument17 pagesCanaza Ecuas 2020 1P PDFAstarot YolicarPas encore d'évaluation

- Sesión 05Document13 pagesSesión 05Hender Samuel Teran EspinozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo Vectorial Abril 15 y 17 de 2020.Document4 pagesCalculo Vectorial Abril 15 y 17 de 2020.KEINER RAMIREZ MONSALVEPas encore d'évaluation

- Apuntes Metodos Numericos Ecuaciones Diferenciales OrdinariasDocument48 pagesApuntes Metodos Numericos Ecuaciones Diferenciales Ordinariasjesus galeaPas encore d'évaluation

- Actividad5 - Cálculo Diferencial e IntegralDocument10 pagesActividad5 - Cálculo Diferencial e IntegralMario Eduardo Najera Ramos33% (6)

- Taller6 2018 IDocument3 pagesTaller6 2018 IDaniela Rojas BetancurPas encore d'évaluation

- Ejercicios TodosDocument47 pagesEjercicios Todoslady lizeth linares santiestebanPas encore d'évaluation

- Ecuacion Diferencial Ordinaria de RiccatiDocument7 pagesEcuacion Diferencial Ordinaria de RiccatiJairo CrPas encore d'évaluation

- 5°.flujo Permanente Gradualmente Variado JepqDocument3 pages5°.flujo Permanente Gradualmente Variado JepqJancileide Elena Patiño QuintoPas encore d'évaluation

- 4.6 Regla de La CadenaDocument3 pages4.6 Regla de La CadenaGuerrero NeftaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Notas de Clase 5Document10 pagesNotas de Clase 5Ruber Ballesteros LoraPas encore d'évaluation

- MATIV Revisión Oct2009Document11 pagesMATIV Revisión Oct2009Yorman A Zambrano PPas encore d'évaluation

- Oscar - Patiño - Tarea 4.Document10 pagesOscar - Patiño - Tarea 4.Oscar PATIÑOPas encore d'évaluation

- Parcial de Calculo 3 Semana 4Document5 pagesParcial de Calculo 3 Semana 4licely orobio castroPas encore d'évaluation

- Analisis de Estructuras RígidasDocument7 pagesAnalisis de Estructuras RígidasJhilmar AlcocerPas encore d'évaluation

- Solucion Numerica de Ecuaciones Diferenciales OrdinariasDocument56 pagesSolucion Numerica de Ecuaciones Diferenciales OrdinariasDiego TapiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Práctica 1 de Ecuaciones Diferenciales PDFDocument2 pagesPráctica 1 de Ecuaciones Diferenciales PDFKevin OvandoPas encore d'évaluation

- PresentaciónDocument6 pagesPresentaciónYadira PaezPas encore d'évaluation

- Maxelia Otazu QuispeDocument7 pagesMaxelia Otazu QuispeMarcial PeñaPas encore d'évaluation

- Derivadas de Funciones Algebraicas y TrascendentesDocument2 pagesDerivadas de Funciones Algebraicas y TrascendentesKaren Gonzalez100% (1)

- Recuperacion Tarea 2Document14 pagesRecuperacion Tarea 2Maury SantiagoPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo DiferencialDocument9 pagesCalculo DiferencialsofPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo 1Document2 pagesCalculo 1ciramdz2720Pas encore d'évaluation

- Números Irracionales Enteros Positivos: Axiomas de La MultiplicaciónDocument6 pagesNúmeros Irracionales Enteros Positivos: Axiomas de La Multiplicaciónnicolecuervo2004Pas encore d'évaluation

- Calculo - Foro 2 BGTGDocument8 pagesCalculo - Foro 2 BGTGGerardo TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- EdpDocument3 pagesEdpΑβγδεΚλμνξPas encore d'évaluation

- Anexo 1 Ejercicios Tarea 4Document22 pagesAnexo 1 Ejercicios Tarea 4Jorge Rodriguez100% (1)

- Ejercicios Ecu. Dif. BernoulliDocument2 pagesEjercicios Ecu. Dif. Bernoullisteven fernandoPas encore d'évaluation

- 2da PRUEBA DE DESARROLLO - Tipo B VirtualDocument16 pages2da PRUEBA DE DESARROLLO - Tipo B VirtualYONMI ORTIZ CCANTOPas encore d'évaluation