Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Representations of Hong Kong in The Films of Wong Kar-Wai

Transféré par

Alex TurnerTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Representations of Hong Kong in The Films of Wong Kar-Wai

Transféré par

Alex TurnerDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Alex Turner 2010

Representations of Hong Kong in the Films of Wong Kar-wai

Alex Turner

Alex Turner 2010 Abstract

The intention of this study is to argue the position that there is a distinct boundary between Hong Kong and the fictional manifestations of it that Wong Kar-wai has chosen to create and to examine the various ways in which the city has been represented over the course of Wongs career.

The dissertation will explore the city through the chapters of places, people and time. The first chapter will argue that the city is often portrayed as a character itself, consistently defining its inhabitants and driving the narrative forward. In addition, the chapter will argue that the creative portrayal of the spaces of Hong Kong is intended to emphasise the symbolically unstable nature of the city. The second chapter will argue that Wongs characters are inflicted by this instability and that the fictional citys inhabitants have become manifestations of a postmodern desire to cling to a fragmenting sense of history and identity. Chapter three will discuss the idea that time as a theme is a binding link between Wongs films, arguing that he consistently uses the city of Hong Kong to explore the nature of time and memory.

The dissertation will then conclude that the city of Hong Kong, as a continuously and rapidly evolving space, has been adopted by Wong Kar-wai to explore the nature of memory in a postmodern world, thus representing the city itself as a postmodern space that is forever physically and symbolically changing, leaving its inhabitants in a perpetual state of nostalgia and isolation.

Alex Turner 2010 Table of Contents

Introduction... Places The Historical (chapter one, part one)... Places The Fictional (chapter one, part two)... People (chapter two)... Time (chapter three)... Conclusion... Appendix... Bibliography... Filmography... 50 23

3 8 14

33 43 46

54

Alex Turner 2010 Introduction

I think the films we have been trying to make try to give you a sense of space, a sense of why this story happens is it because it happens here - Christopher Doyle (The Culture Show 2005)

The aim of this dissertation is to examine the various ways in which filmmaker Wong Karwai has repeatedly used the city of Hong Kong as a key feature in his films throughout his directing career. Through a close reading of his films, this dissertation will extract an understanding of the city as it is portrayed by Wong, concluding in an explanation as to why, in the career of a supposed auteur filmmaker who is considered seminally postmodern, Hong Kong remains a notable constant throughout the majority of his work.

In order to do this, the dissertation will look at three aspects of Wong Kar-wais work and, by extension, of the fictional city of Hong Kong: places, people and time. Each theme will mark a new chapter and will be discussed through the filters of key film theorists and authors, as well as through three of Wongs films: Fallen Angels (1995), In the Mood for Love (2000) and 2046 (2004). By examining the relationship between these three elements and the ubiquitous space of the city, the essay will create an understanding of how the city manifests itself within the fictional space of the narrative, as well as to why Wong chooses to evoke these specific versions of Hong Kong.

Alex Turner 2010 The first chapter will provide a brief history of the city of Hong Kong and its massive physical and economic transformation throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The evolution of this space is key to an understanding of Wongs own translation of it onto film and the first section will explore this relationship. The chapter will then analyse the formal aspects of Fallen Angels, discussing how space is explored and presented within the frame. Additionally, it will consider the use of space in Wongs films in the context of a postmodern aesthetic.

Chapter two will focus on the characters which inhabit the films of Wong Kar-wai and their relationship with the fictional Hong Kong. A brief discussion of the directors literary influences, such as authors Manuel Puig and Haruki Murakami, will be presented in an attempt to understand Wongs persistent use of subjective voiceover and fragmented narrative. Through an analysis of key scenes in 2046, this chapter will explore the idea that each character functions as a manifestation of a postmodern condition which is created, or inflicted, by the city itself.

The final chapter will explore the argument that time is a binding theme of Wongs work, with the city of Hong Kong being a prime space for an exploration of the nature of time and memory in a postmodern world. By exploring the use of mise-en-scne and cinematography in In the Mood for Love, this chapter will attempt to both extract and understand the various motifs surrounding time that appear in many of Wongs films and are essential to his status as an auteur, as well as to an understanding of the ways in which Wong represents Hong Kong in his films.

Alex Turner 2010

However, before the main discussion begins, it may also be useful to explore the directors own, biographical history with the city. Wong Kar-wai was born in Shanghai in 1956 and immigrated to Hong Kong at the age of five. As a young boy growing up in the 1960s, he would often visit local cinemas with his mother (Kaufman 2001). During this time, the people of Hong Kong had little in the way of film and television that was marketed directly toward them and it was not until the latter end of the decade that TVB in Kowloon would become the first broadcasting station in the history of the city to perform this duty (Cheuk 2008: 32).

Consequently, Wong watched a variety of international films in local cinemas, where the concept of genre seemed to take second place to production location. As he explains in an interview with Anthony Kaufman:

In Hong Kong in the 60s, going to the cinema was a big thing. We have cinemas for Hollywood films, local productions, European cinema, but there was no [label of] art film at that time. Even Fellini was treated as a commercial film. [...] And we didnt know which is an art film, which is a commercial film; we just liked to watch the cinema. (2001: Influences).

It seems, then, that cinemagoers of 1960s Hong Kong were exposed to an eclecticism that, perhaps, afforded them a slightly different experience of film compared to much of the

Alex Turner 2010 Occident or even their mainland neighbours who, even today, pass only twenty foreign films each year for cinematic viewing (Dead Mans Chest 2006).

By the time the Wong had left university in the late 1970s, the local TV station had begun training young, unqualified hopefuls in directing and production design. As he explains in an interview with critic Peter Brunette, [...] most of the talent in the Hong Kong film industry came from TV. And you got paid 750 dollars a month (2005: 114). After several years of screenwriting, Wong was given the opportunity to direct his first feature film, As Tears Go By (1988). This first film was, perhaps, his most faithful genre piece to date, though he was already beginning to experiment. As Wong explains, Hong Kong had already produced more than two hundred gangster films. [...] I said to myself, [...] MTVs popular, Ill borrow the form of MTV to make a gangster film and see what happens. This, then, was to be the beginning of the directors hallmark aesthetic, which many critics compare to that of the fast-paced, highly saturated form of the music video.

After his directing debut, Wong Kar-wai departed from genre films almost completely, but his actors, themes and filming locations remained very much the same. Between the late 1980s and 2005 Wong Kar-wai shot and based his films almost exclusively in Hong Kong. Throughout this period in his career the city was represented as a place of duality and opposition, of local and global, private and public, and as a host or catalyst for many things, including nostalgia, alienation and timelessness. In each film, the city of Hong Kong itself becomes an essential character, narrative force or, at the very least, seems to be strongly tied to some of the motifs that have afforded Wong Kar-wai auteur status. The

Alex Turner 2010 coming chapters of this essay are dedicated to exploring both how Hong Kong is represented to us through Wongs directing vision and why this city is such an essential element of his films.

Alex Turner 2010 Places The Historical

There is a response to the energy of this space. The people in this part of town are on the edge of the so-called Western farang [...] and yet, down the street, its very, very, very local. Christopher Doyle (The Culture Show 2005)

The intention of this chapter is to discuss the various ways in which areas of Hong Kong are presented and how the overall space is explored, both formally and thematically, in Wongs films. In order to do this, the chapter will be divided into two sections, exploring the historical and fictional Hong Kong respectively. This first section will discuss a brief history of the city, tracing the economic and cultural changes over the past two centuries and is intended to create a portrait of the city as it is seen today, introducing the physical, architectural and overall tactile form of a historical Hong Kong. This section is intended not only to provide an introduction to the chapter, but also to function as an overview of the city which is relevant to the entire essay. As the intention of this essay is to explore the various representations of Hong Kong in Wongs films, the discussion of physical space and its on-screen portrayal will be prioritized over the subsequent chapters, as the city itself is the most essential element of Wongs work, influencing almost every other aspect of his films.

Alex Turner 2010 The second section will explore what shall be referred to as the fictional Hong Kong, as composed by the director, and will look at various locations within the city, specifically those used in the film Fallen Angels, attempting to draw out the similarities and differences between the abovementioned real and fictional spaces. By a textual analysis of key scenes in the film, it will explore Wongs use and depiction of specific physical spaces. Finally, this chapter will then use the aforementioned analysis to argue that such locations of the city not only act as characters themselves within the film, but often function to drive the narrative. It will also discuss the idea that Wongs city is not only a primarily fictional space but also a postmodern one, and that it harbours an aesthetic of subjectivity which creates a world where nothing is empirical, objective, or definite.

In order to give a comprehensive analysis of Wongs use of and relationship with the space of Hong Kong, it is important to first introduce a brief description of space itself, or, more specifically, of the meaning of space in everyday city life. In his book The Production of Space, sociologist and philosopher Henri Lefebvre gave a detailed description of how social space is constructed in the form of the spatial triad. This triad consists of three interdependent concepts: spatial practice, representations of space and representational spaces. Firstly, spatial practice embodies, as Lefebrve notes: a close association, within perceived space, between daily reality (daily routine) and urban reality (the routes and networks which link up the places set aside for work, private life and leisure). (1974: 38) 10

Alex Turner 2010 In effect, spatial practice refers to daily routine and urban reality; Lefebrve uses the daily life of a tenant in a government-subsidised housing project as an example of this (1974: 38). Representations of space in Lefebvres triad refers to the intangible space linking thought and action. It bridges the gap between conceptualised space and its production, is manifested in the form of delineations such as maps and models and is populated by urban planners, scientists, social engineers or, as Lefebvre notes, all [who] identify what is lived and what is perceived with what is conceived (1974: 38).

Thirdly, representational space is what Lefebvre explains to be a passively experienced space which the imagination seeks to change and appropriate, overlaying physical space and making symbolic use of its objects (1974: 39). It is this final part of the triad that seems most relevant to Wongs work and also, perhaps, many other films produced in Hong Kong. As author Esther Yau notes, Hong Kong filmmakers especially those of the New Wave - often proffer a space-time in which Hong Kong exists in many versions, effectively transforming the city into an unstable symbolic construct (2001: 12). More specifically, in the films of Wong Kar-wai, there appears to be a consistent appropriation of the physical space of Hong Kong which is linked strongly to the representational space overlaying it. It is this relationship which will be explored as the chapter progresses.

11

Alex Turner 2010 The geographical and economic landscape of Hong Kong has altered dramatically since the turn of the 20th century. The Treaty of Nanjing, signed 29 August 1842, saw the island ceded to the British Queen, but it was not until the post-war population boom in 1949 that the city began to take a form more comparable to todays Hong Kong. After the rise of communism in the mainland, immigrants began flooding through the citys borders, their low-cost labour aiding a boost in the economy as industrial businesses began to swiftly rise. By the 1950s, many high rise buildings were erected in order to deal with the growing population, culminating in the construction of such Kowloon residential buildings as Chungking Mansions and Mirador Mansions by the end of the decade (the former would later serve as a shooting location for Wongs films Chungking Express and Fallen Angels). Such spaces often rise up to over fifteen floors (in the case of Chungking, it is seventeen) and support a residential population of up to five thousand (Fitzpatrick 2007).

By the 1960s, what had begun as a small military outpost and trading port was now a sprawling, high rise metropolis. The population of the city has more than doubled in the subsequent forty years and stands, today, at just under seven million (World Bank Group: Total Population). With the rapid economic growth of the city, living conditions have improved dramatically over the past five decades but, in a city with a population density of nearly 6,500 people per square kilometre (Bureau of Public Affairs: Hong Kong (12/09)), it could be argued that space is viewed as something of a commodity.

12

Alex Turner 2010

However, many attempts have been made to use this space as efficiently as possible. Within the hilly terrain of Hong Kong Island, for example, the opening of the Central-MidLevels escalator in 1994 allowed the transportation of civilians up to 800 metres between the residential mid-level areas and central Hong Kong, becoming the longest outdoor escalator system in the world (Boland n.d.). Underground space development in the form of bars, shops and restaurants has become an essential part of urban expansion, both on the Hong Kong and Kowloon side. As more expats, businessmen, families, teachers and travellers continue to take up holidays and homes in the city, residential buildings such as the aforementioned Chungking Mansions on the Kowloon side have, today, become multicultural melting pots, housing up to 120 different nationalities in its many hostels and hotels each year (Fitzpatrick 2007). Such buildings being titled residential serve only as a reminder of their original purpose, as many of the rooms within them now serve a variety of different functions, including internet cafes, import/export businesses and even small accounting firms (see appendix, images 2 and 3).

These aforementioned areas are amongst many of the locations explored in the directors 1995 film, Fallen Angels, which follows the lives of three interlinking characters: a mute thief, a killer and his working partner. As they make their way through the streets, bars and markets of Hong Kongs nightlife, they experience the euphoric thrills of lust, the fanatical melancholy of unrequited love, the unrestrained optimism of having hit rock bottom and the ecstatic catharsis of momentarily breaking through an emotional, existential and physical oppression.

13

Alex Turner 2010

As noted by Peter Brunette, Fallen Angels owes a great deal to Wongs previous film, Chungking Express, as it explores many of the same motifs, locations and characters (Brunette 2005: 59). In fact, the film originated from a third story that Wong had written for Chungking Express, but which was cut for reasons of length (Teo 2005: 83). Like Chungking, Fallen Angels focuses on the themes of isolation, alienation and love in the city and, also like Chungking, it was conceived as a diptych where the characters from each separate story experience fleeting encounters with each other but are otherwise narratively unrelated. However, one of the prime differences, it could be argued, is that Fallen Angels is much more an exploration of physical than emotional space. As Wong himself comments, sometimes the main character is not the actors or the actresses, its the background (Brunette 2005: 119). It is this emphasis on the importance of space and its creative representation which is central to the formation of a fictional Hong Kong. These themes will be discussed in the next section and are intended to establish a direction of influence that will be relevant throughout the rest of the essay.

14

Alex Turner 2010 Places The Fictional

If, as quoted above, Wong sees the background of an actors space as a character, how is this background presented to us in Fallen Angels? Firstly, it could be argued that the use of unusually short focal lengths makes for an interesting portrayal of space. For the majority of this film, cinematographer Chris Doyle chose to use an exceptionally wide 6.8mm lens (Brunette, 2005: 61). The effect of such a wide lens is an unavoidably large amount of distortion, as well as an extreme sense of depth to the image. Formally, as Wong puts it, the use of such a lens gives the audience a feeling of seeing the characters from a distance even though youre very close to them (Rayns 1995: 14).

This effect is perhaps best illustrated in the opening shot of the movie, which sees Wong Chi-ming (the killer) and his agent sit together for the first time in their working relationship. Here, it seems that their time together is coming to an end, as the first line spoken is the agents question, are we still partners? The camera holds a two-shot of the agent and the killer, static but handheld (see appendix, image 4). The scene is barren, desaturated, noisy and highly contrasted. As the edge of the frame shakes with the handheld camera, we feel an affinity with the agents own shaking hand as she struggles to lift a cigarette to her lips. The killer remains silent, motionless. The frame is canted, not only to suggest a moment of tension or unsettlement, but also, it seems, to use every available area of space that surrounds these two characters.

15

Alex Turner 2010 Though the shot is wide and the characters are clearly inside a room, the only recognisable object is an overexposed picture frame; at this moment, nothing else exists for these characters or for us as viewers. With the agents face appearing so large on the screen and so close to the lens we feel pushed into the space and yet, between Wong Chi-Ming and his agent, there seems to be an infinite depth separating them. Through the use of such an extremely wide focal length this scene manages to evoke both a sense of distance and closeness, a shot which has become something of a trademark for the director (Brunette 2005: 62). Here, then, it is not the use of light, colour, soundtrack or performance which is the most striking element of the sequence, but simply the placement of the camera in relation to its subject and environment.

However, despite its attempt to create a kind of tactile or haptic connection between image and viewer, this opening sequence arguably takes place in something of an abstract space which in no way can be linked to that of Hong Kong. It is, in fact, the lack of any signifier of the city in this scene which serves to retrospectively punctuate its narrative importance for the viewer as it reappears later in the film, but this will be addressed in the next chapter. Here, at least, we have discovered that Wongs ability to simultaneously create a sense of intimacy and remoteness is a key factor in his representation of space and that this effect is reproduced on many occasions, especially throughout Fallen Angels.

In addition, this trademark shot is not simply something associated with a certain character or mood, nor does it seem to serve any particular narrative function; it appears when He Zhiwu, the mute thief, is introduced breaking into the storefronts to illegally sell their

16

Alex Turner 2010 products, it shows the long stretch of the killers Kwun Tong apartment as the agent is cleaning it up, it is used when the killer bumps into an old school friend on the bus and in the end sequence which momentarily brings the thief and the agent together, as well as at countless other times.

However, bar the opening sequence, each instance of the shot does appear to create a dialogue between character and environment. For example, the aforementioned sequence which sees the agent entering and cleaning Wong Chi-mings apartment includes a shot of such striking depth that it positions the viewer on the edge of two very distinctive worlds (see appendix, image 5). On the left hand side of the frame we see Wong Chi-mings environment, as a handheld camera looks through the broken window in a voyeuristic manner reminiscent of the cinematography found in Chungking Express. On the right of the frame we see the city, long roads distorted by the wide angle lens, stretching out into the distance. Although it is clear that, physically, the apartment occupies the space of the city, a border appears to have been created between the killer, his agent, and the world outside. Here, it appears that Wong is quite clearly using this trademark technique to invoke a sense of alienation which suggests not a single sprawling, unified space, but a fragmented one where everything is further away than it looks and everyone even the viewer - keeps their distance.

The use of a single lens mounted on a handheld camera is, however, not enough to create an interesting portrait of the city. Other elements of Fallen Angels, such as the editing, contribute to create an overall sense of a claustrophobic, fragmented space. Movement in

17

Alex Turner 2010 the city, for example, is often presented as the traversal of a labyrinthine space, confusing and fast-paced. As we see the killers agent passing through the underground on her way to his apartment, what could be filmed in two or three shots is cut into seven. She moves through the space with a hasty resolve, only ever looking straight ahead and yet, despite her quick, deliberate pace, we are never certain exactly in which direction she is going, or in which direction she came from.

From a variety of angles, the subject jumps around unpredictably in the frame and the shot is never held for more than three seconds. In one shot, she is moving from left to right in the frame, in the next she is moving in the opposite direction (see appendix, image 6). The effect is of both fragmentation and disorientation; we are unable to distinguish how long these tunnels are, nor how long the agent has been travelling through them. Consequently, the space is a potentially endless one, populated only with blocked off maintenance doors and large, concrete pillars, where everything looks alike under the yellow-green fluorescent lighting.

Interestingly, there is also a distinct lack of people in the subway, an effect which enhances the already tangible sense of isolation created through the distinct echo of her clicking heels and the wide angle lens spreading open an already large space. Such an empty area where one would usually expect to find a multitude of people implies a large degree of patience, co-ordination and editing. Here, what could be traditionally presented as a simple transitional sequence has, arguably, been cut together in a manner which reflects the agents response to the city throughout the film as a whole: she is forever determinedly

18

Alex Turner 2010 wandering toward an unachievable end through a confined space, isolated from its other inhabitants and unable to find the right path.

In reality, Hong Kongs Mass Transit Railway system is somewhat different to the space that appears in Fallen Angels, and an analysis of this difference may be key to an understanding of the overall distinctions between the historical Hong Kong and the fictional version that Wong adopts in his films. The aforementioned lack of patrons, for example, is perhaps the most peculiar sight; as an estimated 3.74 million people pass through the MTR on a daily basis (Patronage Figures 2009b), it is reasonable to assume that removing nearly everyone other than the subject in the frame was a deliberate decision.

In addition to this, the image appears to have gone through a process of colour grading, altering the colour temperature of the lighting. The fluorescent lights of the Hong Kong MTR appear, in reality, to be of a considerably warmer colour temperature than in the aforementioned sequence (Webel 2007, appendix image 7). Furthermore, the heavily vignetted, noisy and highly saturated nature of the image is a result of a creative control of the space in both principle photography and post production. Combined, these effects serve to enhance the isolation of the subject that has already been established through the choices of camera placement, soundtrack and editing.

Creating this sense of isolation or separation seems to be one of the most persistent of Wongs goals; it appears consistently in Fallen Angels and may give a clue to the directors primary use of the space of Hong Kong. Throughout the film, it seems that the spaces in

19

Alex Turner 2010 which these characters appear are not simply empty, but are traditionally expected to be full. Images are saturated with signs of a high population: we see motorways, trains, escalators, residential buildings and the clothes hanging between them, as well as scores upon scores of bright neon advertisements fixed onto high rise buildings and shop windows. Despite these signs, however, we rarely see any people at all. It as if, for people like Wong Chi-Ming, He Zhiwu and the agent, very little exists outside the physical and emotional space which they occupy. Consequently, it is not only a sense of isolation but also one of detachment which the film evokes in its portrayal of Hong Kong. Here, we can see that there is some correlation between character and environment; as each of the cast wander, detached, isolated and optimistic through the underbelly of Hong Kong, the spaces, sounds, light and colour of the city seem to reflect their emotional states.

However, if there is a thematic link between character and environment in the film, in which direction does it move? Either the characters emotional states are projected into the external space of the city, or the city itself acts as a catalyst in the moulding of their character. It is here that we can begin to understand the primary use of space in Wongs films, as well as the key differences between the fictional and historical Hong Kong.

If Lefebvre sees representational space as an intangible space of the imagination - of ideologies, theories and visions - superimposed upon physical space, it could be argued that Wong Kar-wai operates within this realm, projecting his creative vision upon a historical Hong Kong. For example, Fallen Angels presents a city that resembles Hong Kong only at its most basic or physical level; we can identify the city through its structures and locations

20

Alex Turner 2010 the football stadium, the residential buildings, the Cross-Harbour tunnel that He Zhiwu passes through several times but these locations are presented to us with a noisy saturation, distorted and seen from obscure angles.

The similarities between the historical and fictional Hong Kong seem to end with the physical, for everything else is a projection of Wongs imagination upon the space; all of the aforementioned formal elements are created or manipulated by the directors vision. The lights and colours that we see, the sounds that we hear and the performances that are given are all elements of a filmic experience that does not exist in urban reality. As Stephen Teo notes, in Fallen Angels, the city has been transformed into a carnivalesque cosmogony, a homology between the body, the dream, linguistic structure and structures of desire. [...] Hong Kong is one big metaphor. (Teo 2005: 93). If, then, Wong uses this space to project his own creative vision upon, it seems that the characters are constructs of the city which, in turn, is a construct of the film itself.

By extension, it becomes clear that Wong utilizes the space of Hong Kong not in an attempt to capture a putatively realistic portrait of the city, but to craft an expressive one of his own that subtlety creates, defines and dictates the actions of the characters in a surprisingly fatalistic manner. This is most evident in Fallen Angels, where characters are predominantly passive; they do not actively seek each others company but, instead, are pushed together by the claustrophobic nature of the city as they happen to cross each others paths in local spaces, such as markets or department stores, for brief moments that only serve to emphasise the lack of physical or emotional connection between them (such

21

Alex Turner 2010 as the relationship between He Zhiwu and Charlie or the killer and his agent). In effect, it is the spaces within the city itself that often serve to weave together the individual stories of these characters which, in turn, influence the narrative.

As Wong has noted on several occasions, Hong Kong is in a perpetual state of transformation (Brunette 2005: 118) and this is reflected in his portrayal of space; Doyles kinetic camerawork is forever attempting to reframe, to form a new relationship between the characters and the space they occupy. The camera is perpetually tilting from left to right, moving closer, backing away or booming up and down during conventionally static shots and characters are consistently boxed in between claustrophobic hallways which radiate exaggerated incandescent oranges and greens and alter their saturation according to the mood of the scene. Comparable to Orwellian cinematography in its subjective approach, it is as though the audience is rarely told how to view the space but, instead, given the opportunity to explore it. It is this portrayal of the city that attributes to an overall postmodern aesthetic which is forever exploring the space from a subjective viewpoint that perpetually changes, creating new relationships or discarding old ones.

Ultimately, if there is one key theme with which Wong approaches the representation of places in his films, it may well be instability. This sense of instability is reflected in all aspects of Fallen Angels, from the constant reframing of a handheld camera, the fast-paced editing and oxymoronic cinematography to the characters own volatile natures as we see them rapidly shift between moments of ecstasy, anger, sorrow and amnesia. Arguably, it is even reflected in Wongs own penchant to shoot without a script (Brunette 2005: 127). In

22

Alex Turner 2010 Wongs films, Hong Kong has indeed become, as quoted above, an unstable symbolic construct, ever-changing (both symbolically and physically) and consistent only in its instability.

It seems reasonable to assume that the nature of such a space must reflect on its inhabitants - indeed, such a notion has already been raised in this chapter but how do the characters found in Wongs films respond to a lifestyle where the empirical, the objective and the definite are rapidly eroding? It is this question which will be addressed in the next chapter.

23

Alex Turner 2010 People

The formal elements are only the uniform, or the clothes. [] What we are interested in, I think, is the people and Hong Kong. - Wong Kar-wai

If Wongs key theme in his portrayal of Hong Kong is that of a physical and metaphysical space in a perpetual state of flux, then the people who inhabit this city often seem to be victims of this world, inflicted with a pathological instability which is a symptom of their environment. But in a world which is, perhaps paradoxically, defined by its subjective nature, where nothing lasts forever and every aspect of daily urban reality is thrown into question and confusion, how exactly do Wongs characters live their lives?

To answer this question the chapter will firstly introduce Wongs literary influences, commenting on the associations between the works of authors such as Manuel Puig and Haruki Murakami and the characters found in Wongs films. The aim of this section is to emphasise not only a relationship between themes and styles explored, but also to reveal Wongs own literary approach to filmmaking an effect which often crucially enhances the subjective nature of his films, highlighting individual moments and character above overarching narrative. Secondly, this section will take the idea of passive characters that are defined by environment (as established in the previous chapter) and, through an analysis of Wongs 2004 film 2046, explore the ways in which characters are affected by the instability of the city they inhabit. Thirdly, this chapter will use the aforementioned

24

Alex Turner 2010 analysis to argue that, as a result of Wongs vision of the city, characters have become manifestations of a postmodern condition which transforms its victims into vehicles of nostalgia, hyperreality, pastiche and intertextuality, seeing them as lovelorn, nostalgic amnesiacs, wandering the streets of Hong Kong without ambitions or objectives, living only in the present or fetishizing moments of their past. Ultimately, this chapter will seek to establish the idea that the characters which inhabit Wongs Hong Kong function less as believable, relatable individuals and more as artistic expressions of a certain way of life and as manifestations of the postmodern desire to cling onto a rapidly collapsing and fragmented history.

Of the author Manuel Puigs work, particularly Heartbreak Tango (1969), Wong comments on its fragmented nature, noting that the structure was just chopped down and constructed with different orders. But it works at the end. So Im trying to do this kind of thing (Brunette 2005: 115). Discussing Puigs influence on his second film Days of Being Wild (1990), Wong describes the structure as having four movements:

The first was very Bressonian with lots of close-ups. The second had the look of a B movie. The third was filmed in deep focus. The fourth looked more like the second, with lots of mobility. The story moved equally from one character to the other, which made the different movements more visible. (Ciment 1995: 42)

25

Alex Turner 2010 Like Heartbreak Tango, it seems that Days of Being Wild subverts the conventional three act structure in favour of a deeper understanding of characters that existed in a specific, albeit profilmic, time and place.

Continuing the custom of literary influences, Wongs main inspiration for Chungking Express was a short story by author Haruki Murakami (Teo 2005: 50) but, as with Days of Being Wild, there was little comparison between influential source material and Wongs films in terms of actual plot content. By this time in his career, in fact, it seemed that Wong had acquired a proclivity for taking themes, styles and narrative structures from predominantly literary sources, transposing them onto film through the filters of his frequently re-used cast and production crew.

The works of Murakami consistently focus on the nature of alienation in contemporary society. In nearly all of his novels, the main character will relay a story to the reader through a first person narrative which often includes the loss of a loved one, the mundane nature of urban reality and the projection of fantasy upon it, as well as a deeply rooted internal conflict which spans the length of the story and which may or not be resolved by its end. As this chapter will go on to explore, many of Murakamis themes are present in Wongs films, although, in practice, they are not literal adaptations of the source material but, instead, parallel the sources content in themes of isolation, alienation, love and loss, subjectified through the first-person narratives of an ensemble cast. Ultimately, the connection between author and filmmaker here appears to be the focus on life in a postmodern world.

26

Alex Turner 2010

Arguably, a filmic exploration of such a life requires a specific focus on character which sometimes, as Wong has admitted (cited above), sacrifices conventional narrative thread for a deeper understanding of the human psyche - a trait shared with Murakami. Perhaps the best example of this is found in 2046, Wongs last film set in Hong Kong. The plot of 2046 follows the character Chow Mo-wan previously seen in In the Mood for Love - over a period of two decades as he attempts to gamble, flirt, sleep and write himself out of the pain of losing a loved one. Along the way, he is joined by a supporting cast of characters from some of Wongs previous films, including In the Mood for Love and Days of Being Wild, who often appear to trigger, within Chows character, a longing for the past. Consequently, it is possible to see 2046 as something of an end of era film, or a culmination of Wongs work to date which revels in its intertextuality. However, for the purpose of this chapter, the most important element of 2046 is its relentless obsession with nostalgia and memory and how these themes are channelled through the main character.

The film opens with a computer-generated cityscape of a sprawling metropolis (see appendix, image 8). Its colours are even more intensely saturated than one has come to expect from a Wong Kar-wai film and the architecture, peppered with Chinese, Japanese and European structures, resembles an already hybridised Hong Kong pushed to the very limit. The line in the year 2046 every railway network spreads the globe is spoken over these images and we are presented with a short sequence following a Japanese character, Tak, on a train leaving 2046. Instantly, the question is raised as to whether these numbers refer to a time, a place, or perhaps both. Tak explains that people travel to 2046 in order to

27

Alex Turner 2010 recapture lost memories, but nobody has ever returned. After discovering, through voiceover, that Tak has lost a loved one and refuses to elaborate, we are taken back into 1960s Singapore, where Chow attempts to convince a woman sharing the same name as his lost love to return with him to Hong Kong. He fails, returning alone, and struggles to make a living as a writer amidst the 1966 Kowloon riots. As the film progresses, we discover that Tak is actually a character in one of Chows novels and is intended to be autobiographical in nature.

Arguably, these few opening scenes reveal a wealth of information on the relationship between the historical and fictional Hong Kong, as well as on Wongs literary influences, funnelled through the crafting of Chow. For example, the choice to open with a CGI cityscape resembling Hong Kong instantly evokes a sense of the hyperreal, of a space where the hierarchy of the authentic and the ersatz has been eroded (if not reversed) and where fantasy and reality have effectively collided. As author James Udden has noted, these opening shots could be read as:

[...]a hyperurban landscape [which] denies the viewer any fixed sense of place. Adding to this spatial disorientation is an unidentified voiceover, not in Cantonese, nor even in Mandarin, but in Japanese, informing us that in 2046 every railway network spans the globe and nothing changes. By all appearances, then, this is a transnational, postmodern landscape where every place has become indistinguishable from every other place. Local history has ceased to exist. (Udden 2006: 67)

28

Alex Turner 2010

Given the representation of the city in Fallen Angels as an unstable symbolic construct it seems pertinent that, here, we are presented with a world that appears as a fictional Hong Kong in overdrive; it is as though this is the final evolutionary step of the space that Wong has been aiming to evoke throughout his directing career. In 2046s future, the meaning and representation of Hong Kong as a space has become so polysemic that the empirical and objective have utterly disappeared and all that is left are memories. By extension, Chow Mo-wan seems to be the final evolutionary step of the characters that inhabit the fictional Hong Kong; once we realise that this futuristic space is actually a construct of the characters imagination it is possible to see Chow himself as a vehicle of postmodernity.

However, it is only after this dialogue between a past and future Hong Kong has been established that we are introduced to Taks (and Chows) story, where we learn that both characters have suffered a loss and that this loss is a catalyst for many of their actions, primarily their unwavering focus on the past. Here, there is a connection with the works of Murakami in the themes of loss and nostalgia; the characters of both Wong and Murakami are consistently inflicted with the loss of a loved one and, through the use of first person narration, the audience is invited to share in their reflective, self-centred musings which often descend into absurdity and a blurring between the lines of fantasy and reality. In addition, the structure of 2046 which employs a dual narrative as we follow what are effectively two interconnected layers of Chows psyche is highly reminiscent of Murakamis Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (1993).

29

Alex Turner 2010 As postmodern theorist Jameson notes, this sense of finding an often false comfort in the past is both indicative of a collapse of history and a hallmark element of the postmodern condition (Friedberg 1993: 168), but this will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter. Here, at least, it is demonstrated throughout the film that, to Wongs characters, not only is past considerably more important than future, but that their fixation with it inevitably leads to a warped sense of history and, by extension, to the collapse of history as an objective metanarrative.

This fixation manifests itself perhaps most strongly in the use of voiceover. The narration is consistently retrospective as Chow will often evoke several versions or moments of history in a single sequence. For example, in a scene toward the end of the film, we return to Singapore to discover that the woman he was asking to leave during the opening of the film is named Su Li-zhen. After discovering her name is the same as his lost love, he references, in voiceover, Wongs previous film In the Mood for Love (A few years ago, I fell in love with another mans wife) and begins to fall for the woman purely from what the audience can discern because of her name. If we presume the voiceover to exist, temporally, ahead of all events in the film, then here we are presented with a confusing state of affairs: the present Chow is discussing a moment in his past which triggered a nostalgic recollection that projected his past emotions into his present during a sequence which, itself, is a flashback. It seems as though Chow and the film itself is relentlessly reaching for moments of the past.

30

Alex Turner 2010 As we are presented with flashbacks of ITMFLs events, we can see that 2046s Hong Kong is aesthetically distinct; indeed, it is a different version of the city altogether, where the muted browns and vibrant reds of ITMFL have been replaced with a high contrast image that mirrors the fictional world of Chows futuristic story (see appendix, images 9 and 10). Here, then, the history of the city has become fragmented into versions which serve as a source of inspiration for Chows creative nostalgia. Through his voiceover, we are forced to see the world through his eyes and, by extension, the existence of his voiceover is the only thing which we can be certain of. Consequently, both Chow and the audience are placed in a perpetual present which is forever looking back to the past: it is feasible that Chow could be sitting alone in a room, sometime after the recalled events, relating this entire story to us as the film conjures up images which represent areas of his memory.

However, the quality of the voiceover itself appears, more than anything, apathetic. Chows matter-of-fact tone and perfunctory vocabulary evoke an emotional stonewall, suggesting a man who has opted to trade his feelings for the safety of never having to be hurt again. Instead, he internalises his emotions, or at least conceals them from the outside world and, with his venture into dramatic writing, projects his own, emotionally-battered self onto the character of Tak. It is only through this character that Chow begins to express his feelings.

This internalising of emotion by a main character is something which appears in a variety of Wongs films and, as with 2046, the characters choose to express their feelings in strange ways, if at all. Here, Chow visualises himself as a Japanese man in the future. In

31

Alex Turner 2010 Chungking Express, Tony Leungs character begins talking to flannels, soap and teddy bears in his apartment, urging them to cheer up. In Fallen Angels, the agent seduces a jukebox which was once used by the object of her desire. These, it seems, are the actions of characters that are unable to cross the barrier between fantasy and reality and are, therefore, unable to function in the space outside their own minds. Rather than actively seeking a solution to their problem, redemption for their actions or closure from their past, they retreat into their own psychological spaces, shutting away the antagonistic world outside and addressing the audience from the vantage point of hindsight.

It is this desire to retreat, internalise and otherwise hide from the increasingly confusing, fast-paced and ever-changing lifestyle that the city has constructed for its inhabitants which defines many of Wongs characters. It is as if the city itself is an inescapable force, forever watching and forming these characters as they attempt to cope with an urban reality which is forcing them into isolation and seclusion. It is only in brief moments of escape that these characters are able to express themselves, as in the opening shot of Fallen Angels which sees the agent and the killer deeply connected through their work and feelings for each other meet for the first time in complete isolation, or in Chows fictional time odyssey.

Ultimately, if these characters are, in fact, manifestations of a postmodern condition inflicted by the space of Wongs hyperreal Hong Kong, then a pattern begins to form throughout the directors work. From the creation of an unstable city where a sense of local history and identity is rapidly disappearing, to the study of characters that retreat from urban reality into the fantasy of their own minds and hopelessly grasp at moments of a past

32

Alex Turner 2010 perverted by nostalgia, Wongs exploration of time as a theme appears consistent. Time, it seems, is a primary theme of the directors films which binds together all characters and narratives. In Wongs films, Hong Kongs identity and history is consistently changing over time, leaving its inhabitants in a reclusive state of longing. It is this theme which will be explored in the next chapter.

33

Alex Turner 2010 Time

Things change very fast in Hong Kong. The locations of my first two films have disappeared already. [...] The lifestyle of Hong Kong in certain periods... Im trying to preserve it on film. Wong Kar-wai (Brunette 2005: 118)

To suggest that the space and characters of the city are connected by an overarching metanarrative of time seems like a truism but, in the films of Wong Kar-wai, the concept of time appears as a crucial component, taking on myriad forms and meanings. Memory could be said to act as the mediator between us and time; it is how we understand that time has passed, or predict that time will ostensibly continue on into the future. In Wongs Hong Kong, time is manifested in a non-linear fashion; crowds bustle through streets at high speeds whilst characters take an eternity to lift a cup of coffee and take a single sip. Minutes and seconds are fetishized, characters eroticise possessions that once belonged to their unrequited love and the tempo of life constantly jumps between violently adrenalinefuelled and nostalgically languorous; here, time does not simply pass, it is felt.

The intention of this final chapter is to explore the argument that time as a theme is a primary element of Wongs filmic pursuits which not only binds together characters and spaces, but also the various fictional versions of Hong Kong which Wong evokes in his films. In order to achieve this, the chapter will be divided into three sections. Firstly, it will consider the connection between postmodernity and time as a metanarrative. Secondly, it

34

Alex Turner 2010 will apply this understanding to an analysis of the film In the Mood For Love (2000) in order to extract a connection between the fragmented, subjective nature of Wongs films, the city of Hong Kong and the nature of time and memory in a postmodern world. Finally, the chapter will use this analysis to argue that Wong, as a director, writer and supposed auteur, acts as a distorting filter between the historical Hong Kong and its fictional counterpart, envisioning the city as a place of perpetual change and instability where he, like his characters, is forever grasping onto an increasingly elusive sense of history and identity.

In his book on Wong Kar-wai, Stephen Teo discusses the notion that the director, along with many other Hong Kong filmmakers of his generation, shares a concern for Hong Kong as a geographical and historical entity (2005: 6). Citing an interview with Wongs old collaborator and friend, Patrick Tam, he goes on to say the directors Hong Kong heritage is:

[...] a heritage always in danger of disappearing due to Hong Kongs special position as a post-modern city perched between East and West, where its space becomes difficult to represent in terms of traditional realism, because history goes through strange loops. (2005: 6)

Here, it seems, a connection can be established between Hong Kong, postmodernity, the nature of time and Wongs films. But what is the relevance of this in the context of Wongs

35

Alex Turner 2010 representations of Hong Kong and how can postmodernity be defined within this context? As a temporal concept, Anne Friedberg notes:

Post implies historical sequence, a moment of rupture when the post succeeds the past. But, as historiographers remind us, history is not only a discourse but a product of discourses. (Friedberg 1993: 161; her emphasis)

Of course, it seems logical to assume that postmodernity would succeed modernity as a moment in history, but even this is thrown into question as Lyotard describes postmodernity as modernity in the nascent state (1984: 79). In addition, the discussion of postmodernity in theoretical discourse has led to myriad interpretations and definitions including:

[...]the end of Enlightenment [or] the site of the Enlightenments completion, [] radical pluralism, multiculturalism, centralized

marginality [and] a culture of decentered subjectivity. (Friedberg 1993: 167)

As for the place of memory and time as a metanarrative in postmodernity, they, too, seem to be affected by a pervasive subjectification. Lyotard marks postmodernity as an end of the grand narratives, such as salvation, emancipation, the dialectic [and] scientific knowledge (Berger 1999: 36). Huyssen extends this dialogue to include a sudden obsession with the past and a fear of forgetting, as well as the media (cinema included) as

36

Alex Turner 2010 primary carriers of memories which, as often as not, are perverted or fabricated (Huyssen 2000: 24-25).

This postmodern fear of forgetting seems to manifest itself cinematically in what theorist Frederick Jameson refers to as the nostalgia film. As Friedberg notes, this nostalgia is an indication of a key aesthetic symptom, a cinematic version of postmodern style (Friedberg 1993: 168). She goes on to discuss the nature of this postmodern style and it is perhaps worth quoting this paragraph in full:

Although Jameson doesnt perform an exact taxonomy, his descriptions divide the nostalgia film into: 1) films that are about the past and set in the past (Chinatown, American Graffiti); 2) films that reinvent the past (Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark); and 3) films that are set in the present but invoke the past (Body Heat [...], Miami Vice, Moonlighting, Batman). The nostalgia film is described in stylistic terms cases where a films narrative and its art direction confuse its sense of temporality. Films such as Chinatown and The Confirmist take place in some eternal Thirties; beyond historical time. (Friedberg 1993: 168)

If, then, both the end of enlightenment and the replacement of time as a metanarrative with a warped, global memory maintained by the media are key elements in the definition of postmodernity, there appears to be a connection between the nature of Wongs Hong Kong and postmodernity itself: both appear to deal with erosion of the objective and the

37

Alex Turner 2010 empirical. Just as Hong Kong has become a city of rapidly changing identities and multiculturalism, of the disappearance of the local and the boom of globalisation, the ambiguity of postmodernity itself appears to embody the very thing it seeks to define. Both share a common trait of polysemy and Wongs city, with its constantly changing spaces, unconventional camera movements and subjective first-person narratives, reflects this throughout his entire filmic career. However, perhaps the most fitting of Wongs films for a discussion of the role of nostalgia and memory is In the Mood for Love (2000).

Set in Hong Kong in 1962, In the Mood follows the story of Chow Mo-wan and Su Li-zhen as they move into neighbouring apartments. After a time, they begin to suspect their spouses of extra-marital affairs and form a brief friendship as they attempt to re-enact the moment in which the first move was made.

Aesthetically, one of the primary differences between In the Mood and the directors previous films is that of camera movement. Discussing the film at Cannes in 2001, Wong notes a deliberate change in tempo:

We build the whole rhythm of the film so Chris Doyle knows how to dance with the camera. Because otherwise he would just do it like Chungking Express. I told him that this was not Chungking Express, you have to be very quiet. You have to be very stable. (Brunette 2005: 130)

38

Alex Turner 2010 The affect of this new style which involves the banishing of the handheld camera in place of tripods, tracks and jibs is that of alienation. In terms of cinematography, it appears highly reminiscent of Resnais Last Year in Marienbad (1961) or of the opening sequences of Hiroshima mon amour (1959), films which, interestingly, both deal with the subjective nature of memory, confusing the audience with similar techniques of alienation and narrative confusion. Combined with a more neutral colour palette which sees Doyles traditionally over-saturated representation of Hong Kong space considerably toned down, a lack of subjective first person narration and an editing style which appears to balance character and narrative equally, In the Mood creates a nostalgic recollection of a period in Hong Kong which seems in comparison to Wongs previous films significantly more grounded in reality.

However, as with 2046, there is still a pervasive sense of creative control with the use of intertitles. The film opens with a reference to what can only be assumed is an important moment in the relationship of the two main characters.

It is a restless moment. She has kept her head lowered to give him a chance to come closer, but he could not for lack of courage. She turns and walks away.

Unlike much of Wongs use of voiceover, these intertitles are written predominantly in the present-tense and appear to chapter certain moments in the story of Chow Mo-wan and Su Li-zhen, an effect which places the viewer more directly in the moment and, at first glance, contradicts the alienation techniques found in the cinematography. However, their main

39

Alex Turner 2010 function appears to be a highlighting of the warped nature of personal memory and it is this which associates the intertitles with the other formal elements of the film. For example, the final title we see, after Chow Mo-wan visits Angkor Wat sometime after the main events of the film, reads:

He remembers those vanished years as though looking through a dusty window pane. The past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.

With this intertitle, an important connection is established between the events of the film and the nature of time and memory in postmodernity. Peter Brunette interprets this title as tell[ing] us all we need to know and retrospectively explain[ing] the films technique (2005: 100). However, whereas Brunette attributes the longing, the frustration and the unfulfilled desire primarily to the realms of adult love and existential longing (2005: 100), it could be argued that the film given its painstaking recreation and presentation of 1960s Hong Kong - transcends this theme into an exploration of personal memory. Given its place in the final frames of the film, it is possible to see this text as being the epilogue of the story which preceded it and, therefore, the Hong Kong that appears in In the Mood is a nostalgic construct, a personalised and romanticised view of a specific period in the citys history. Here, it seems, there is both a longing for the past and a distortion of history which is bound inexorably to the city itself.

40

Alex Turner 2010 If we are to examine the film with the idea of the city as a catalyst for nostalgia in mind, the formal elements of In the Mood begin to generate new levels of meaning. For example, much of the space portrayed in the film, just like Chows memory, is obscured. In the opening sequence, each shot seems composed as a distancing mechanism; walls, curtains, lamps, doorframes and tenants consistently obscure the subject from the audience (see appendix, image 11). The characters respective spouses are never seen, even in sequences where they have relatively large chunks of dialogue and, as a result, the shot-reverse-shot style of shooting dialogue is all but abolished. Shots linger where they are traditionally expected to cut, focusing on door frames, handles and light switches which have been briefly touched by Su or Chow, mimicking the obsession of memory traces such as the jukebox in Fallen Angels, or the apartment in Chungking. Here, however, it is not a character in the film that is focusing upon these traces, but the film itself.

Combined, these elements create a technique of distancing which, as Brunette notes (quoted above), is encapsulated in the final intertitle. However, unlike Wongs previous films, the cinematography is wholly objective; we are never given a point of view to attach to and the distinct lack of wide angle lenses that have been so prominent in films such as Chungking, Fallen Angels, and Happy Together denies us the ability to be pushed into the space. Here, the image is consistently flattened, the colours toned down and the frame obscured. The space is extended by the use of sound (we constantly hear the chatter of other tenants in the building, diners in the restaurant and passersby in the street), but this space is almost never shown to us. In addition,

41

Alex Turner 2010 moments of increased emotional proximity between the two characters are shot at a languorous pace, accompanied by a romantic cello piece and focusing on small motions such as Su and Chow brushing past each other on the stairs, sequences which appear as a recurring motif throughout the film (see appendix, image 12). It seems that, here, no single character is obsessed with memory or time, but instead the film itself takes the role of the lovelorn nostalgic, recalling, in obscured detail, an era of Hong Kongs history which is no longer present. Indeed, as Chow returns to the apartment some years after, the penultimate intertitle states:

That era has passed. Nothing that belonged to it exists anymore.

Such intertitles are the key to understanding the formal construction of the film, as they consistently lead the viewer not only to envision a romanticised period of Hong Kongs history, but also to compare it with the contemporary manifestations of the city in Wongs other work.

However, unlike previously discussed films such as Fallen Angels and 2046, which invite the audience to focus primarily on the nostalgia of love and loss and an obsession with the past using the main characters as a proxy, In the Mood generates nostalgia for an entire albeit short - period of history which ended with the beginnings of Hong Kongs cultural revolution in 1966. Clocks, as with many of Wongs other films, are ubiquitous, but in this film intercut between tracking shots of lavish art deco apartments and the flowery cheongsam dresses of Su Li-zhen - they appear to signify not only the loss of a certain

42

Alex Turner 2010 moment, but of time itself as loss. As Wong himself notes, in several interviews, in reference to Days of Being Wild:

[...]Since I didnt have the resources to re-create the period realistically, I decided to work entirely from memory. And memory is actually about a sense of loss always a very important element in drama. We remember things in terms of time:Last night I met... Three years ago, I was... (Brunette 2005: 20, Rayns 1995: 14)

The Hong Kong of Days of Being Wild is set in the sixties, but the society as shown in the film never really existed like that, its an invented world, an imaginary past. (Brunette 2005: 20, Ciment 1995)

If, then, Days of Being Wild was Wongs nostalgic recollection of a Hong Kong during social upheaval in the latter half of the 1960s, it could be said that In the Mood is an exploration of the city during what Wong appears to envision was its golden years, a time when his parents would have been living similar lives to that of Su and Chow.

Ultimately, it seems that the theme of time and memory in Wongs films is the strongest binding link between not only the films discussed here, but those spanning his entire career. It is, however, In the Mood for Love which seems to be one of Wongs most personal projects, making it not only a fictional manifestation of a historical space, but an exploration of personal memory and the malleable nature of time.

43

Alex Turner 2010 Conclusion

The intention of this dissertation was to identify, explore and discuss the various ways in which Wong has represented the city of Hong Kong throughout his directing career. In terms of space, we can conclude not only that Wong consistently creates a strong link between Hong Kong and his characters, but that the city itself is presented as the source of instability which defines them.

By extension, this ubiquitous sense of instability affects each character in several ways. Firstly, it sees them often unable to grasp onto a sense of identity, causing them to retreat into the space of their own minds (giving only the audience the ability to hear them through the use of voiceover). Secondly, as a result of this instability, each character seems plunged into a perpetual state of nostalgia, attempting to recall a time when things were different (such as the mutes recollection of his childhood in Fallen Angels or Chows various manifestations of Su Li-zhen in 2046).

Combined, the influence of such an unstable environment and a persistent focus on what could have been, or what once was, establishes a running theme throughout Wongs work on the relationship between time, memory and loss. Given its transformation over the past century (as discussed in chapter one), Hong Kong seems to be a prime location for a filmic exploration of this as the city noted in several references throughout this essay has become synonymous with postmodernity in relation to the boom of globalisation, the

44

Alex Turner 2010 hybridisation of its local culture and the distinct sense of a space that has been partially defined by its ability to adapt and transform, physically, socially and economically.

In addition each film discussed in this essay could be seen as an exploration of Hong Kong at certain periods in history. Through an auteurs creative vision, Fallen Angels examines city life as it is today, 2046 as it is destined to become, and In the Mood as it once was. Through these films, Wong seems to have created a timeline which follows the city through a process of metamorphosis, with each transmutation affecting the lives and identities of its citizens.

However, several questions are still left unanswered. Firstly, what exactly are the differences between the historical and fictional Hong Kong? Although this question has been raised and, to a small degree, addressed in this essay, a more in-depth study of the historical timeline of Hong Kongs cultural and economical climate over the last century would be required in order to provide a satisfying answer. In addition to this, in order to keep the essay as structured and focused as possible, the event of the 1997 handover has been avoided an event which critics such as Teo and, to a lesser extent, Brunette purport to be a major influence in films such as Happy Together and 2046 (indeed, the year 2046 refers to the final year of Chinas fifty year promise to govern Hong Kong as a special administrative region). It seems only logical to assume that further research would reveal a relationship between this state of political purgatory and Wongs films.

45

Alex Turner 2010 Ultimately, this dissertation can conclude that, through an analysis of some of Wongs most celebrated films, there is not only a certain disparity between the historical Hong Kong and its fictional counterparts, but that Wong has adopted this city to examine the nature of time and memory in a postmodern world, thus presenting Hong Kong itself as a postmodern space.

Consequently, it seems reasonable to assume that, if Wong is ever to return to Hong Kong as a director, his work will continue to focus on the unstable nature of the city and its ability in his creative manifestations of it to inspire a longing for identity and a resulting obsession with nostalgia; qualities which appear inherent not only in his characters and the city he creates, but perhaps in Wong himself as a filmmaker.

46

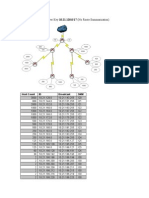

Alex Turner 2010 Appendix

Image 1 ( Alex Turner Photography):

Hong Kong Island as viewed from the Kowloon side.

Image 2 ( Alex Turner Photography):

The interior courtyard of Mirador Mansions.

Image 3 ( Alex Turner Photography):

A hallway of Chungking Mansions containing a hostel and internet cafe. 47

Alex Turner 2010 Image 4 ( Jet Tone):

The killer and his agent meet in isolation.

Image 5 ( Jet Tone):

The space of the killers apartment and the world outside.

Image 6 ( Jet Tone):

The agent paces through the empty Hong Kong subway.

48

Alex Turner 2010 Image 7 ( Jet Tone):

Hong Kongs subway, before the colour correction of Wongs post-production.

Image 8 ( Block 2 Pictures/Paradis Films/Orly Films/Jet Tone):

The CGI cityscape of 2046.

Image 9 ( Block 2 Pictures/Paradis Films/Orly Films/Jet Tone):

Saturation and grading comparison between 2046 (left) and In the Mood (right)

49

Alex Turner 2010 Image 10 ( Block 2 Pictures/Paradis Films/Orly Films/Jet Tone):

Saturation and grading comparison between 2046 (left) and In the Mood (right)

Image 11 ( Block 2 Pictures):

The mise-en-scne consistently obscures the cameras view.

Image 12 ( Block 2 Pictures):

Fleeting moments of physical and emotional contact in In the Mood for Love.

50

Alex Turner 2010 Bibliography

Anon. (2006) China Sinks Dead Mans Chest Available: http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2006/jul/10/news1 Last accessed 27 December 2009

Anon. (2009a) MTR Available: http://www.mtr.com.hk/eng/homepage/cust_index.html Last accessed 30 January 2010

Anon. (2009b) MTR Patronage Figures For December 2009 Available: http://mtr.com.hk/eng/investrelation/patronage.php Last accessed 30 January 2010

Baudrillard, Jean (1994) Simulacra and Simulation USA: University of Michigan Press

Berger, J. (1999) Postmodern Catastrophe and Post-Apocalyptic Desire: Until the End of the World After the End: Representation of Post-Apocalypse Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota

Boland, R. (n.d.) Hong Kongs Central-Mid-Levels Escalator The Longest in the World Available: http://gohongkong.about.com/od/whattoseeinhk/a/midlevelsescala.htm Last accessed: 10 January 2010

Brunette, P. (2005) Contemporary Film Directors: Wong Kar-wai Chicago: Illinois

51

Alex Turner 2010 Bureau of Public Affairs. Hong Kong (12/09) Available: http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2747.htm Last accessed: 6 April 2010

Carter, C. (2007) East Asian Cinema China: Kamera Books

Cheuk, P.T. (2008) Hong Kong New Wave Cinema (1978 2000) Bristol: Intellect

Ciment, M. (1995) Entretien avec Wong Kar-wai Positif 410

Doyle, Christopher (1997) Dont Try For Me, Argentina: A Photographic Journal Hong Kong: City Entertainment

Fitzpatrick, L. (2007) Best Example of Globalization in Action Available: http://www.time.com/time/specials/2007/best_of_asia/article/0,28804,1614524_1614473_1 614447,00.html Last accessed 9 January 2010

Friedberg, A. (1993) Looking Backward An Introduction to the Concept of Post Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press

Huyssen, A. (2000) Present Pasts: Media, Politics, Amnesia Public Culture 12.1

52

Alex Turner 2010 Kaufman, A. (2001) Interview: The Mood of Wong Kar-Wai: The Asian Master Does It Again. Available: http://www.indiewire.com/article/decade_wong_karwai_on_in_the_mood_for_love/ Last Accessed: 22 December 2009

Lefebvre, H. (1974) The Production of Space Translated from French by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell

Lyotard, J. (1984) The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge Manchester: Manchester UP

Murakami, H. (1993) Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World Vintage Books: New York

Puig, M. (1969) Heartbreak Tango London: Penguin Classics

Rayns, T. (1995) Poet of Time Sight and Sound 53 (1), 12-16

Teo, S., (2005) Wong Kar-wai London: British Film Institute

Udden, J. (2006) The Stubborn Persistence of the Local in Wong Kar-wai Post Script Vol. 25 No. 2, Winter/Spring, 67-79

53

Alex Turner 2010 Webel, S. (2007) Subway Available: http://stevewebel.com/photographer/tag/subway/ Last accessed 31 January 2010

World Bank Group, The. Hong Kong Total Population Available: http://datafinder.worldbank.org/population-total/chart Last accessed 6 April 2010

Yau, E. (2001) At Full Speed: Hong Kong Cinema in a Borderless World Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

54

Alex Turner 2010 Filmography

2046 Wong Kar-wai (2004) China/France/Germany/Hong Kong

As Tears Go By Wong Kar-wai (1988) Hong Kong

Chungking Express Wong Kar-wai (1994) Hong Kong

Culture Show, The #3.6 (2004) [TV progamme] BBC, BBC2 19 May 2005

Days of Being Wild Wong Kar-wai (1990) Hong Kong

Fallen Angels Wong Kar-wai (1997) Hong Kong

Hiroshima mon amour Alain Resnais (1959) France/Japan

Last Year in Marienbad Alain Resnais (1961) France/Italy

In the Mood for Love Wong Kar-wai (2000) Hong Kong/France

55

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Movie Minorities: Transnational Rights Advocacy and South Korean CinemaD'EverandMovie Minorities: Transnational Rights Advocacy and South Korean CinemaPas encore d'évaluation

- Berg (2006) A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films - Classifying The "Tarantino EffectDocument58 pagesBerg (2006) A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films - Classifying The "Tarantino EffectPhilip BeardPas encore d'évaluation

- Kurt Kren: Structural FilmsD'EverandKurt Kren: Structural FilmsNicky HamlynPas encore d'évaluation

- The Law of the Looking Glass: Cinema in Poland, 1896–1939D'EverandThe Law of the Looking Glass: Cinema in Poland, 1896–1939Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Beginnings Of The Cinema In England,1894-1901: Volume 1: 1894-1896D'EverandThe Beginnings Of The Cinema In England,1894-1901: Volume 1: 1894-1896Pas encore d'évaluation

- Point of View in The Cinema - de GruyterDocument2 pagesPoint of View in The Cinema - de GruyterXxdfPas encore d'évaluation

- Decentring France: Multilingualism and power in contemporary French cinemaD'EverandDecentring France: Multilingualism and power in contemporary French cinemaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mosaic Space and Mosaic Auteurs: On the Cinema of Alejandro González Iñárritu, Atom Egoyan, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Michael HanekeD'EverandMosaic Space and Mosaic Auteurs: On the Cinema of Alejandro González Iñárritu, Atom Egoyan, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Michael HanekePas encore d'évaluation

- The life of mise-en-scène: Visual style and British film criticism, 1946–78D'EverandThe life of mise-en-scène: Visual style and British film criticism, 1946–78Pas encore d'évaluation

- Film Culture on Film Art: Interviews and Statements, 1955-1971D'EverandFilm Culture on Film Art: Interviews and Statements, 1955-1971Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tom McSorley - Atom Egoyan's 'The Adjuster' (Canadian Cinema)Document112 pagesTom McSorley - Atom Egoyan's 'The Adjuster' (Canadian Cinema)Jp Vieyra Rdz100% (1)

- Birdman: or The Unexpected Virtue of IgnoranceDocument18 pagesBirdman: or The Unexpected Virtue of IgnoranceAjiteSh D SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- The Young, the Restless, and the Dead: Interviews with Canadian FilmmakersD'EverandThe Young, the Restless, and the Dead: Interviews with Canadian FilmmakersPas encore d'évaluation

- Casablanca - The Theater Play (Based on the Original Film): Adapted by David SereroD'EverandCasablanca - The Theater Play (Based on the Original Film): Adapted by David SereroPas encore d'évaluation

- The Cinema of Mika Kaurismäki: Transvergent Cinescapes, Emergent IdentitiesD'EverandThe Cinema of Mika Kaurismäki: Transvergent Cinescapes, Emergent IdentitiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Revolution in the Echo Chamber: Audio Drama's Past, Present and FutureD'EverandRevolution in the Echo Chamber: Audio Drama's Past, Present and FuturePas encore d'évaluation

- Zones of Anxiety: Movement, Musidora, and the Crime Serials of Louis FeuilladeD'EverandZones of Anxiety: Movement, Musidora, and the Crime Serials of Louis FeuilladeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1)

- Sentimental Fabulations, Contemporary Chinese Films: Attachment in the Age of Global VisibilityD'EverandSentimental Fabulations, Contemporary Chinese Films: Attachment in the Age of Global VisibilityÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Interrogating the Image: Movies and the World of Film and TelevisionD'EverandInterrogating the Image: Movies and the World of Film and TelevisionPas encore d'évaluation

- Berlin School Glossary: An ABC of the New Wave in German CinemaD'EverandBerlin School Glossary: An ABC of the New Wave in German CinemaRoger F. CookPas encore d'évaluation

- Agents of Liberations: Holocaust Memory in Contemporary Art and Documentary FilmD'EverandAgents of Liberations: Holocaust Memory in Contemporary Art and Documentary FilmPas encore d'évaluation

- Kim Ki DukDocument6 pagesKim Ki DukRajamohanPas encore d'évaluation

- Hungary Hamlet in Wonderland Miklós Jancsó's Nekem Lámpást Adott Kezembe As Úr Pesten (The Lord's Lantern in Budapest, 1998)Document14 pagesHungary Hamlet in Wonderland Miklós Jancsó's Nekem Lámpást Adott Kezembe As Úr Pesten (The Lord's Lantern in Budapest, 1998)Pedro Henrique FerreiraPas encore d'évaluation

- The Repr. of Madness in The Shining and Memento (Corr)Document62 pagesThe Repr. of Madness in The Shining and Memento (Corr)Briggy BlankaPas encore d'évaluation

- What Film Is Good For: On the Values of SpectatorshipD'EverandWhat Film Is Good For: On the Values of SpectatorshipProf. Julian HanichPas encore d'évaluation

- Brief Glimpses of Beauty-Jonas MekasDocument1 pageBrief Glimpses of Beauty-Jonas MekasHector JavierPas encore d'évaluation

- Media PresentationDocument7 pagesMedia Presentationapi-356813854Pas encore d'évaluation

- Essay On 16mm FilmDocument7 pagesEssay On 16mm FilmPanos AndronopoulosPas encore d'évaluation

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Playwright as Historian: From Christopher Marlowe to David HareD'EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Playwright as Historian: From Christopher Marlowe to David HarePas encore d'évaluation

- (Thompson, Kristin) Space and Narrative in OzuDocument33 pages(Thompson, Kristin) Space and Narrative in OzuAgustina Pérez RialPas encore d'évaluation