Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Body-Parts Reliquaries-The State of Research

Transféré par

maplecookie0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

163 vues13 pagesThis essay surveys the state of research on "body-part reliquaries" emphasis is placed on French works, a number of which survive and about which there is documentation. This essay was first offered at the College Art Association in San Antonio in February 1995.

Description originale:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThis essay surveys the state of research on "body-part reliquaries" emphasis is placed on French works, a number of which survive and about which there is documentation. This essay was first offered at the College Art Association in San Antonio in February 1995.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

0 évaluation0% ont trouvé ce document utile (0 vote)

163 vues13 pagesBody-Parts Reliquaries-The State of Research

Transféré par

maplecookieThis essay surveys the state of research on "body-part reliquaries" emphasis is placed on French works, a number of which survive and about which there is documentation. This essay was first offered at the College Art Association in San Antonio in February 1995.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 13

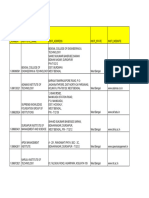

Bod-Favl BeIiquavies TIe Slale oJ BeseavcI

AulIov|s) BavIava BvaIe BoeIn

Bevieved vovI|s)

Souvce Oesla, VoI. 36, No. 1 |1997), pp. 8-19

FuIIisIed I International Center of Medieval Art

SlaIIe UBL http://www.jstor.org/stable/767275 .

Accessed 26/03/2012 0717

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

International Center of Medieval Art is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Gesta.

http://www.jstor.org

Body-Part Reliquaries:

The State of Research

BARBARA DRAKE BOEHM

The

Metropolitan

Museum

of

Art

Abstract

For the first time since the nineteenth

century, pub-

lished

articles, monographs, conferences,

and lectures

dedicated to the medieval cult of relics have

proliferated

during

the

past

decade.' Studies

specifically

of

reliquar-

ies that assume the form of

parts

of the human

body

have

begun

to

occupy

a small corner of this field of

research. The newness of this

pursuit

in literature

pub-

lished in

English

is evidenced in the rather awkward

and

inelegant

term

"body-part reliquaries"

that has been

adopted

in the context of this

publication

of

papers

that

were first offered at the

College

Art Association in San

Antonio in

February

1995. This

essay surveys

the state

of research on

"body-part reliquaries." By way

of

specific

example, particular emphasis

is

placed

on French

works,

a number of which survive and about which there is con-

siderable documentation. Given the

perspective

of the au-

thor,

a museum curator and

specialist

on the

subject

of

head

reliquaries,

consideration is also

placed

on the in-

stallation of such

reliquaries

in American museums and

what that

suggests, historically,

about their

perception

as

works of art.

Throughout

the nineteenth

century

and until well after

the Second World War the

study

of

reliquaries,

and within

that context the classification and

study

of those whose con-

tainers assume the form of

parts

of the human

body,

was

largely

the

province

of historians drawn to their

subject

either

by

virtue of their vocation in the Roman Catholic

Church,

or

by

their interest in national

patrimony.

One of the earliest

scholarly investigations

of the medieval veneration of

saints,

including,

somewhat

incidentally,

the enshrinement of their

relics,

was written

by Stephan

Beissel in 1890.2 Beissel was a

member of the

Bollandists,

a Jesuit

group

devoted to the

study

of

hagiography

and

responsible

for the

publication

of the Acta

sanctorum and the Analecta Bollandiana.3 The first

encyclo-

pedic attempt

to discuss and

analyze

the medieval

production

of

reliquaries

of all

types

was written

by

Beissel's student and

fellow

Jesuit, Joseph

Braun. While

teaching archaeology

and

art

history

for his order at

Valkenburg, Frankfurt,

and Pullach

near

Munich,

he

published probing

studies on focused themes

of the

liturgical arts, including

Der christliche Altar in seiner

geschichtlichen Entwicklung (Munich, 1924), Die liturgische

Gewandung im Occident und Orient nach Ursprung und Ent-

wicklung, Verwendung und Symbolik (Freiburg

im

Breisgau,

1907), Sakramente und Sakramentalian

(Regensburg, 1922),

and Das christliche

Altargeriit

in seinem Sein und seiner Ent-

wicklung (Munich, 1932). Within this context, Die Reliquiare

des christlichen Kultes und ihre Entwicklung

was

published

in

Freiburg

im

Breisgau

in

1940,

with an introduction

by

the

author

signed

on the Feast of Pentecost and

bearing

the nihil

obstat of the

Society

of Jesus.

Braun listed both

surviving

and recorded

reliquaries,

exhaustively tallying

their number over the course of Middle

Ages,

as well as the Renaissance and

Baroque periods.

He

classified

reliquaries by

their form. Under the rubric of "Re-

dende

Reliquiire"

("Talking Reliquaries"),

which included all

manner of

reliquaries

whose form

apparently

related to the

relics

they contained,4

he first listed

examples

in the form of

a

foot,

then others

shaped

like a

hand, finger, rib, arm, leg,

followed

by figural reliquaries

in the form of a head or bust.

For

reliquaries

in the form of a head or a bust

alone,

over 150

examples

were cited. Braun's work established an

approach

to

the

subject

that has been

imitated,

but not

surpassed, by

iso-

lated

publications

since 1964

by Kovaics, Bessard,

and Falk.5

Churchmen likewise

played

a role in the

numbering

and

study

of medieval

reliquaries preserved

in France. Abb6 Tex-

ier noted the

presence

of

forty-seven reliquaries

in the form

of an arm in churches of the Limousin alone.6 The

publica-

tion

by

Bouillet and Servibres of the

Majesty

of Saint

Foy

at

Conques,

the

golden image

that enshrines the head of the vir-

gin saint,

and their translation of the

legend

of Saint

Foy

into

French,

were done in the

years immediately following

the bish-

op's investigation

of the relics in the nineteenth

century.7

An

introductory

letter from the

bishop

of Rodez and Vabres de-

clared the book to be "une oeuvre

d'apostolat capable

d'6difier

les

ames," noting

that

"l'aimable

sainte vous a

d6j'a marqu6

sa

gratitude par

les satisfactions

qu'elle

vous a

prodigu6es."8

Overall, however,

the

study

of

reliquaries

in France has

largely

been advanced

by

historians concerned with docu-

menting

national

patrimony.

The first

example

of a

body-part

reliquary preserved

in France-the head of Saint

Maurice,

commissioned

by Boson, king

of Provence from 879-887 and

brother-in-law of Charles the Bald-was described in 1625

by

Nicolas Fabri de

Peiresc,

an

indefatigable

historian and

naturalist.9

Its appearance

was recorded in two

pencil

sketches

as

part

of his wider

investigation

of

important

monuments of

the

history

of

France, including

the vessels

preserved

at Saint-

Denis, notably

the chalice of Abbot

Suger.10

The

pivotal

article

discussing

the

reliquary

recorded

by

Peiresc in the seventeenth

century

was

published by

Eva Kov~cs

only

in 1964.11 The bust

reliquaries

that formed

part

of the

treasury

of Saint-Denis are

recorded

among

and

alongside

a wide variety of

liturgical

ob-

jects

in the

engravings

of the cabinets published by Dom M.

F61ibien,

Histoire de l'abbaye royale de Saint-Denys en France

8 GESTA XXXVI/1

?

The International Center of Medieval Art 1997

1~~~~1)-

g> ..

P; .

-~~

~

,..T:i

.

......:

FIGURE 1. Saint-Nectaire, Bust

Reliquary of

St. Baudime, as recorded

by

Anatole

d'Auvergne,

Revue des societ~s savantes, ser. 2, 1

(1859) (photo:

Bibliotheque nationale, Paris).

(Paris, 1706).

The

appearance

of the head

reliquary

of Saint

Louis from the

Sainte-Chapelle

was recorded as the frontis-

piece engraving

for the 1688 Paris edition of Joinville's His-

toire de s. Louis IX. In the nineteenth

century,

the

journals

of

French

archaeological societies,

on both the national and local

levels,

were of

great importance

in

making

known

reliquaries

like the bust of Saint Baudime at

Saint-Nectaire,

recorded

by

Anatole

d'Auvergne

in 1859

(Figs. 1-2).12

Ernest

Rupin

discussed a number of

reliquaries

in the

form of busts in a

separate chapter

of his

book,

L'Oeuvre de

Limoges, published

in Paris and Brive in 1890. As a native of

the

region,

and sometime

president

of the Soci6t6 arch6o-

logique

et

historique

du

Limousin,

he dedicated himself to

publishing

the metalwork that he attributed to the Limousin.

In so

doing,

he classified

reliquaries by

their

form, noting that,

while the

majority

of

reliquaries

contained bodies or

body

parts,

it was often the case in the Middle

Ages

that the "enve-

lope"

reflected the contents.13

Rupin

also

published

an article

li iiiiii ii

.................................................................

:: : : : : :: : : : :: : : : : : : I: : : : : :: : : : :':::::

i

iiiiii iii iii i iiii iiiii iiii iiii ii i

~i::i - ::: :: :: :::_::::i::::i ::::?::::_:-::_-:-: -:-:: --:: :-: :-: :-:_ :: ::-: . -::- :_: _:- -: ::_- :::: ::::::: :::: -::: ::: ::: : :: :::::- --:- : ::- :: -:: ::

:::: ::::::: :::: : : : : :: ::: ::::::::::: ::: :::: :::: ::: ::: : ::: ::: :

iii~i!7 7 ii~iiii~!!i~i!!!!!!!:i i: !! !! !!! ! !! !!! ! !!! i!

iiiiii~i~ iii~iT~iii i :: :: :: : :: : : ::::: :: :: :: :: : iiiii :i

:::: : :: :: : : : :: : :: : :: : : : : ::: ::: ::: ::: ::: : :: :: ::: :: :: : :: ::: :

: : :: : : : :: : :: : : : :: : :: :: ::: ::: : : : : : : : :: :: :: : :: : :

:::: :: _i i: i-

i:ii

i

iii i i iii

FIGURE 2. Saint-Nectaire, Bust

Reliquary of

St. Baudime, 12th

century

(photo:

Caisse nationale des monuments

historiques

et des sites, Paris).

on one head

reliquary

in the

region,

the head of Saint Martin

from Soudeilles.14

His work did not

pass

without

notice,

for it was in the

context of

Rupin's publication

that two

examples

were

pre-

sented to J.

Pierpont Morgan,

the American banker whose

vast collection of medieval art forms the nucleus of the Me-

dieval

Department's holdings

at the

Metropolitan

Museum.15

Both

the bust of Saint Yrieix

(Fig. 6)

and the one of Saint

Martin-then in

parish

churches of the Limousin and now in

the

Metropolitan

Museum and the Louvre

respectively-were

acquired

for his collection in the first decade of this

century.

Morgan's acquisitions

of these

objects along

with other

liturgical

arts seems to have been a function of his own keen

antiquarian

taste and the

development

of his

"princely"

col-

lection,

rather than of his own faith

(Morgan

was an

Episco-

palian)

or of his national

heritage. Henry

Walters of

Baltimore,

a Roman Catholic and

Morgan's only

real rival as an Ameri-

can collector of medieval

liturgical art, apparently

did not have

9

ii-i-i i-i iii-i-i:iii i-iii

i::-i2

i-i

ii

ii-i

:

iii-ii i~i~i~i ::i--::'

W -

.0 .1::

FIGURE 3. Bust

Reliquary of

Saint Juliana, After 1376, New York, Metro-

politan

Museum

of

Art

(photo: Metropolitan

Museum

of Art, New

York).

a taste for

"body-part" reliquaries. Morgan's

interest does not

seem to have been

shaped by

mainstream art

history,

but

by

the

example

of French amateur

collectors;

there was no

Berenson-like

figure influencing

his choice of these

singular

works of art. In

fact, beyond

the confines of Roman Catholic

literature and discussions of

patrimony,

art historical

study

continued to

ignore

such

works,

and when

discussing them,

to be dismissive of them.

As national

treasures, reliquaries

in the form of

parts

of

the

body

were

important

items in the

great Exposition

Uni-

verselle held in Paris in 1900. The culmination of the inves-

tigation

of such

reliquaries

as national

patrimony

was the

1965 exhibition

Trhsors

des

eglises

de

France,

which included

nineteen head/bust

reliquaries

and

twenty-one arms,

as well

as foot and

thigh reliquaries.16 By contrast,

two

years

later,

the

international loan exhibition held at

Cleveland, Treasures from

Medieval

France,

focused on

sculpture

and

manuscripts.17

Al-

though

it featured thirteen works of art that likewise had

figured

in the Paris

show,

it included but a

single example

of

a bust

reliquary

and none of other

body parts.

By

this

time, body-part reliquaries

had

begun

to enter

into art historical literature

following

Harald Keller's

theory,

---

II :I

:

:-:-:

ii

-:::

:::'

i ii ::'

- i:ii

-:::::

i

-i:

: 1

i

:- --_

: i :iii~

:: :: 1 -:

;-----------

- ::-- : ::- i:- i:::i- _:_-:;iiiii~iiiwi.~~i:iliiii:_ii:-- ii::: -,-,~.~?iiisiiaiiii''i:iiisiiii : :: -i-i--:i- -:: :

FIGURE 4. Bust

Reliquary of

Saint Juliana

(as

in

Fig. 3), x-ray photo-

graph of

wooden core with

gesso build-up (photo: Metropolitan

Museum

of Art, New

York).

published

in

1951,

that

they

were

key

elements in the rebirth

of monumental

sculpture.

Keller asserted that the individual

limbs and truncated torsos

represented

the first

attempts

on

the road to

representing

the entire human

figure.18

It was this

line of research that informed a number of

subsequent

con-

siderations of this material. In the 1950s Rainer Riickert be-

gan

a

study

for a doctoral dissertation on the

subject

of head

reliquaries. Again,

the

principal

motivation was the exami-

nation of the "evolution" of medieval

sculpture.

The result

was an

important

article on

sculptural

metalwork of the

Limoges region,

without further

investigation

of the bust

reliquary

as a form in Western medieval art.19

The

only publication

on

reliquaries

to follow the

Tresors

des

eglises

exhibition was entitled "Les Bustes

Reliquaires

et

la

sculpture."20

The

single entry

on a bust

reliquary

in the

Cleveland

catalogue

of Treasures

from

Medieval France dis-

cussed the work as the

equivalent

of a Renaissance

portrait

bust-emphasizing

the

degree

of naturalism it

achieves, sug-

gesting again

an

"evolution,"

towards the canon of Renais-

sance art.21 For American scholars of the Renaissance,

such

as

Irving

Lavin22 and Anita

Moskowitz,

the

importance

of

bust

reliquaries

has been their

relationship

to Renaissance

10

portrait

busts,

Moskowitz

maintaining

that

"reliquary

heads

and busts

tend, throughout

the Middle

Ages,

toward

portray-

als that

suggest

individual likenesses."23

In an American museum context the treatment of

body-

part reliquaries

has likewise focused on them as

portraiture.

Of the four busts of

companions

of Ursula in the Metro-

politan,

three were

purchased

between 1959 and 1970. The

papers

for their

acquisition

stressed their

importance

as

por-

traiture,

and

indeed,

their installation until the late 1980s

atop

a credenza at The Cloisters was a

setting

more

appropriate

to

Renaissance busts than to devotional

objects.24

In

addition,

museums have

pursued

what

might

be called

the

archaeology

of

reliquaries, meticulously examining

their

construction and their contents,

rather than

considering

them

for their aesthetic

importance

or historical context. A notable

example

was Paul

Pieper's study

of the Head of Saint Paul at

Miinster, published

in

1967,25

and Rudolf

Schnyder's

of the

head of Saint Candidus.26 In

1963,

Thomas

Hoving

examined

the bust of Saint Juliana at The Cloisters

using x-ray

technol-

ogy (Figs. 3, 4), just

as the French had done for the

image

of

Saint

Foy

at

Conques. Perhaps

unable to shake the

parallels,

he theorized the existence of an earlier male bust

underlying

the

princess-like

Juliana, just

as

Taralon, similarly,

had iden-

tified an

imperial

Roman mask as the face of the

virgin

martyr Foy

at

Conques.27

It was not until the

publication

of

the

Thyssen

collection in 1987 that what

Hoving

saw as the

peculiarities

of the Juliana bust were

explained

in the context

of Sienese

polychromed sculpture.28

As a

result,

its relation-

ship

to lost

reliquary

busts such as those of Peter and Paul

made for the Vatican29 or the Bust of Saint

Agatha

in the trea-

sury

of Catania30

(Fig. 5)

was overlooked.

The

disassembling

of the

reliquary

of Saint Yrieix

(Figs.

6, 7)

at the

Metropolitan

Museum in the 1960s

provides

a

particularly telling example

of this

approach

to

body-part

reliquaries. During preparation

for the

Tre'sors

des

dglises

ex-

hibition,

it came to the attention of French and American art

historians that there were two versions of the

reliquary.

That

this fact had not been

explored

since the

acquisition

of the

reliquary

in 1917 is in itself testament to the inattention these

works of art have received. The

response

was to

strip

the Saint

Yrieix in New York of his silver

sheathing.

In

fact,

careful

comparative

examination of the

examples

in Paris and New

York based on

existing

Monuments

Historiques photographs

would have shown conclusively

that the New York example

was the original,

even though

the relic itself had been trans-

ferred to the

copy

in France in 1907. Since the 1960s the wood

core and silver revetment of the reliquary

head of Saint Yrieix

have been exhibited side by side, the prevailing opinion being

that the core, a masterly piece

of Gothic wood carving,

is too

beautiful to cover.

Such thinking springs

from a

prejudice

in art historical

literature that undervalues "minor arts" like goldsmithswork,

and especially sculpture

in

precious

metal. The 1975 edition

of Gardner's History of

Art includes no body-part reliquaries

S- - :'- ----- ----- - ----- -------------- ::- : : -:: -: : : -::

mft? ;x..

FIGURE 5. Bust

Reliquary of

Saint

Agatha,

14th

century

and later, Church

of Sant'Agata,

Catania

(photo: after Rossi, 1956).

of

any

kind. In

fact,

Gardner illustrates no

Romanesque

or

Gothic

goldsmithswork,

at all. The one inclusion is a Caro-

lingian

bookcover-the Codex Aureus of Saint Emmeram.

In

periodical

literature

reliquaries

have been considered

par-

enthetically

in relation to other

questions.

For

example,

the

head

reliquary

of Saint Alexander

preserved

in Brussels has

been examined

chiefly

for its

importance

in the

beginnings

of

champlev6

enameling.

Other forms, especially

arms,

but also,

exceptionally, fingers

and

thighs,

have

barely

been considered

at all.31

This

disregard may

be attributed,

in

part,

to the fact that

so much

goldsmithswork

has been

destroyed,

and

that,

in

American museums,

it is

particularly

rare.32 But I would ar-

gue

that

reliquary sculpture

has been not

merely

undervalued,

but,

in some circles,

considered

suspect,

as well.

Although

body-part reliquaries

were embraced as a

subject by

Roman

Catholic historians in

Europe, they

were

generally rejected

as

a

subject

of serious research in America. An

important

ex-

ception-and virtually

the

only

discussion in

English

of bust

11

. .... . ....

.-_. ........ .

. ... .

: -_i:--Al-

.... .. ... ... . .

.i

...........~

4M.Aia-:

... . ........

ii~i ...... .......~

......... ....... .

..... . . . . . .- i : ii

..........ii l ii -i . i iii

....

......- -i

All ol.!R?!?2

.. ........'ii

:-i': ii..............

A. . .... .... ........

i-i~ii-_i:iiiiiiii :.. . iii -ij~-........ .........~-:li

-- W ..........

. . . . .........

..... ..... . ..... ... ...

.......

... . ... . m

-: -: i:-:-: . i-ii

-i-.

.. .........i~i

. . . .... ..

.. .. ...

: : iEii'i~i~fliiiiiir:r'lr";ass p ~ l~,.. . . ........._ir-

. . .......

FIGURE 6. Bust

Reliquary of

Saint Yrieix, the silver

casing,

12th

century,

New York, Metropolitan

Museum

of

Art

(photo: Metropolitan

Museum

of Art, New

York).

12

- " I .... I'll .-,-. .

. .".

...

1. -111 - . -., 1? ?::, ? -- I ? -'?..'?Iz .1 M. ,x, . ? . . k??: .. .. MIM , ,MM.M?...,... . - , - . , . . ..- - ,

??, ,:?? ,::? ?::K:::?o.

?

... . . .. I " , .. .. .. ,?:?m

. m -,gmm

; . ?

Mr., WWR?'.i

?

"I.", ,

.

Mom ?g ... . NN ' ,, ,... * . 1.11, . X.? .1 ,

I...,-"-.,.

1-.11.11.1. ., . ?

?.,??..xi??.??:?

x g

........... .. ? W ......

::.*.

0 - - -

g - . a

, I.. ,....-- -,%..? -

.

?.,-. ... , .. . I W "', .. -

ll- -

..., 1% I

?'-'-' M

Z

?a ....

lt.v MH ?', .. .

.M l.- ...?.,... .. I

,? ,

,- ......... ", ......... ... 11 - . ... I ..

I

, I - - l ...- --l- ...

ft'.

M . ....

- ?::: "%.-

..... .::

ii ??, ,,?.?,??n.:.?

,:: M

... ?, P ......,

, I sm :,:::: ...

,

.... .. - m

.. ....

.

. ..... .. ?o , ?? ... .

?? ':

.

M. " ? - --:--:-:? ?0 3.

m! ?

. . .. - ,...........- ... -.. ..,

MA"

I ,.,x

.. . ...

. . . . . . . . , , , ", I ? ? . . . ,??.R':

. .

.?. V,

. . . . x , . : 4 ::., :.- .

x .

.-

....;,.?..

--,...'.............

" . .. p

-:..??: E I .I.: I.. .1R.IX .

'..;-;-..;.:..l,? ... p

. .

.. M.. --Xm...

-:..

...-

1.1-1-1. - -.?.?...-

ll.,?--

..... - . -

??.,, -..

-11.

? .....1

", ... I .... .

,w 7

? , ?

??::::!?.:::??,,.??:?,???:,.::?:?

.

,.::: ... I .m ...... .. . ...? ...

,., .

' ... ..

- - ",-:-.............

.....- . ..

I

.'. ?'., ", - ? ,-- ,,....,. .I .

. I . ? .:::?::

::?:::%:?:,:.:.,

. .. . ? 1, ?. x- -, - . .l. -

.... . ?. ,.t , ??; ??.: . . .1 . . . .1.

...

.

",

hL.

.-

-,,?:,.:

k -, IV , -. ..

.

. . , . .. 11

W-??:::,M ?.,

.

.

. .

. . ,:: :::?, - .:?,??,'?

::- - - ... ,..-,...I..

... ...

............... .....

... .

. ," ::. .-...-....-.......... . ... . ... . I

....'..........

....

.. ":" ??..,...V?..?.?-1.?..?..?..%.,?lI

.

. .

.. I -:-::-: - .

....

. . .,-..-....-: 5:?- -- - ..:?..:: ..... . . .

.....

1. - ? ................. .... ...... .

-.-

?.

..:?::...,:

.::?

.

..

.

. ? ::?

.:.- .- .:.::.....?.:..V.:.:

.., .. . . . . ..

:.. ? 1.? ?,-- .... l-.-%.-.., .. . ... ,--., :, I - :? . . . .. . . ...... ....... ..... -.A '. ..... - . . . . . . . . . ... ... . .. . . . : . . .1 .. ?: .

I......

I ,

. ...

?

....,

.

..... I....

. .

. . . - I . I . . I . .

. . ? . . , .. . . .

? ., -... - .. . . . ., : . . . . . . . . . .. ... .. ,., , . : .,.,.::: : I . .... . .. ,?

j........Xm.

11,

::?...?:??: :,? x . . . . I . ': , - . . ... , , . , ... ..

, : ? .: ,,: ?x.:??,?::?. .. I . .. ,:--, I -? ..... %,. ....

.

..

- .,-...-..-........... . ?? .. ? ? v- ... F ..... v ...... % ... ... I..''... . ... zll?'- . .,:.? M::??::. ... - . , . :,::: . :::-.-:::?.::-:-

. :,.-?

. ? .? I.I.- ? ? ? ? ........... - . I ?. , .. I... .. .. ... ... ... . I ., ?

I... - .. .- : -:- ? ?;:. - ..-.::, .. Mll? -

- ?::-,-:- ?__- .... ? .. - . -, ... 11-1 - .

...-.. .. ,. ,., ? ?. ..-..........??.....?......,...........?...- ,. .. 0- - : I X:: ? ,....,... ,. I : -... 11 , ., ,

,?.

t2 ---..." ... ji .? - .. .. .. , .

:. - -..: ...... ? . ..................... ....

I'.,.

- .

-:-,.::..--

,:.

...

- ...

I

;. ...-

.- := ,- ..:,-- . .... .: P ?? - Z: .. --... . - , . -.- . . .. . " . -.1.

- .. - ... ... .. . .

-

. ?

.. ::: ::: ::: ::" .:,: :- .:..:- ... .. :::: .

I ?

11 ... -:-- -. .. .1 ?

"... - . - . . . . ................... I ... ? ....... ... - %V-M-%. ,... ? .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. ..

. v,?::?- ............ I ... I.. :? - :-- - .............. . .. '

'.. .. .. .' '. . ...... .. .. ....- ,

-- -,,,.:,::.-

..

- ,-:- ... %.- .-..-. ,?.?

. ? ... 1. ??VT, MEAL

-

4 ... . --, .-

-,?..%

-....- . ...... .. ".-I. , . , . - .

:::'l.,:l

.l..",l ? ?.,.:.-- .. : . .::, K- - ?- ?- . 1

I... ,

m - - .. ...

.

... I.:.,:: I.....- -...,....,-. ::.z".? 1. .! ,

?? .. ...... .... ?:,i: .....

..? .

I

-

-

?

... %.- ...

V- -

...

?-

?

-- .....

,

:-.1???,.?l.,-".,??:,:.,.?.:.:..''.:-

,. I -

.?.: m'

??. ,

- - . . , ? ?Kll.? , ill

'I"

.. . ... -, ?:, - - :,?:.:,?: . .... . :.: .. ?W lk?r:% : ,. .g,,.:.: ..l. I... . I ? . .% " ".:. .,: ..

??

- ? .... . x

.: .

:

,

" I ... ... .:.:-- - ,. - , ..... I.. : ., . , & ..;, . , .. . -- ,- . ...... -,.- .-...-..l .............. 11 ........ 11 .... ' ... I ??::??:??:?:??: .. ' .... :::?::- :::,.- ?: . .1

.??:,??:??:?

... : :??:??:::?.??:?:?M

1: ll? - :

- :.?::?.: ?:::,:. ::, -

"I .11 ?.....

kxlm'2111.--... ...,.,r

.

:::,?.? ?.M . ',::?:::?:- . . - . - :1 I . ....... - .:.' ' . I ?. ..

'.1

. -j . ::. ,

- .. ."

:

;?,??ff, .

-

-...m .-.:: .

I . . I .11 .... ? ?.. ? ....... ?....., ... . %,,-,- ..,.l...- ... ... ... ?. " ,.,..% ... ..... ?.._ - .. -

Y '..."....:.. , ,- ..,...... ,- . - m.. ... X ?

::i.4 .....:xx

ii?. .....'......... I.. I - 11 . . . . . . . . ... . - f.. ? ,

::::.,?.::....:.::??:..:?:?,i:::?:?:::::

" . ... I.. I .

. ... . 1

.1 ...

,:. ? . .... - .. :::F. -? ..'? .I.... :

.11 - - .. ... ? ............. 9 :

%?:

. .m. . . I ... -:-,-??::-:? .. .... . , - ., - ?'... I .......... . .. M ... . : ; , -

,.? .

. : ,

:

, :,:, ..?'. X:...??:.?.:::

. ....

... ,

?

-11-1- I - - - * e

- . .

, .1 . - .:::,.

?: .

&??.'Xmm.-----

- ., - . - . .

-

- . - . ..... .

M

. ??.,.

.......

..:

. . . - .. .1 .. ,... :- , 'k.:.

....... 1.11-1

. ... ,

??

.

: .11.- - , ...... ;; . .......... . .. : . I .... - .. . ... .. ...

??::???:::

.

".. ? ,* ,." ? x? .... . ?? : -

. .... . . ... ..

... . ..? ....I., ?

.....'...

: % ::- . I . :X, .

-.-.., ?...::: : 7?1.11

, ,-

-....--d

. - ..:.:? . 0 1 ?

R. ,. I

.11'..,.,..-",.- ,. ....-........-

I.- I M

- .. . ...... - ::????i

.i;

.

... - .... I ... .... ... ?i? . .. ... ... .. .. , ?

.

- ? . .?,:,?W . , ???:.. . - , ?::.----% ... .. . ? ;, ... ........... ? ....-........'?..,......,......-. a

a m .:.:., .

......,...?. ..,......,..,...,...?.."..., ...... ... .. :.:: : I.- I -,. ... -..::..:...

::]:?:?:i :.." . -., ..

..*I.:

-

::x::?n" '.

... :?. ff . ..... - .,.l..ll I......,....".........

.....

? ,

.

.??::?.-::i:: W M ?,.zM .111-1.1 1 .. ?: , ?? ... ..: ,?: ?i9

oWw'.o:a

.

. - .. .. ... 1:

..

. :?:??:?:-??M m ? ::?: . ,; . I

.P

:-:::, .1 ..... .-.... '... M .1 - ?; ... .. .. , F,

X...:....X?.?

?,:- : ... .... . .. - - . . : .I........ .: . ?.. ?M " I .

..

. .

11-1 I'l- ,.- -? ? ? ..... . , :....

.- ............ . .

. I ..

.....

? ?

?::.?

x

.N...;

x . 00".M :.:: - ... , ...

. ,

.

.3

.

m

R'n'. N R ...... , -- I ... .:. ..::??-: ?. o I .,

W. ..?.a . . . - .... ...........

..

.

.....

W .

. :

:?.,...'?. 90 .0 - - - . I . . vxlox.,.:?,? ? ....m??

:.- ?-, I ... . " '. M

.. ?."..". ::

i?:w

. -

:

-

,:,:. - ., . .. - .. - . . . . . . - w .. :::

.%

::.?? . . . ?. ft: 1 .. - , ... .

... - ? . .: ?.. - ... . .- ....-,-,...,.._.. -m m

..

. .? . . -... . . . . . .

- - 1. %n? . ...... .. - .. ...?:::: I. ,:?, ,........................... , , . ....-... . It

. .

.

... . .. ..

.. ... .. N. a I ?? ,.??:?-.:--,- ?

, r ,. :..

4xi

..!...-.i?i

.. . %::- 1- 1:? -::

?x M ?

? .. .... ... .. ? .. - - .. , I ..F...X. I n

..... . :? -

...

I

w w om m

....... ..

. : ?.?mj??,*M.q .. , .. :!::

................ ?,? ?,

.. . ?e ,:.:? .. 1

... .. '. " - . .... ? .. .... : Z:: %,: ,_.. - I., .

-. ...7%,Xl -.:::?.

. ......

a ?? im

. . I ... -

"

.........

. . :

W . ?04.- ...... V. .. A, Q V i::: ej.,? - .:..:::m: .

.....?.:. zk 9 '. I .

M NIM?? .- : - ,:.... m - ... \ .-.. ?--... .-... . ... I .: . ..

'.

. . ..

.11

.? ,

.1.

xw

. .. . ....

.

.....

. . ...... . '. ..... :::::..:x , . ?. :. . - ....... ... I I.- I... "I

-

::::,:A l l .... o ... .. i, ?? . ,? ............

..

-- - ..... ? .. .! - M .. 0 .1-1-"?WM ........,. ,. .. .?

??

:

W .W ., . . :M

.. . '? 1. 'l l ...... .N;*. .- .... ff

p

.?

...... : ? ? ? :: -X I . "

?1,1.3..W?- .-..... ...............?..

e? .. .1 ... ?? .1 ? W, .

I

M

.:.: A .: -.-, -11-.. . .... I I - ? ,

1. ? .

N l,:?i?a "

I

.. -,... ,-.-

...

M

.: .

. ....

..

. ... .... . -

:lz-.:..'?:.:,:,??. .:??....:!:..:: :?V::

F lx. 1: ... I.... ? .,?*% .'- .,..-

.

....

'

.

.?. . . ..". ,4V ..?'. - 1 ... ?%e .. ........ . .. . ll?:?:?M ?:?? . ... -

?.

,? .........

... , . - .

11.1 ..... ?.

I .?: .:: ?I?i

W : ..l. -1 ?

:....... %:

.

. A- W - , - ... "..'', ,.-:.:,, % :::?i- .?i?? .....-... U .. 11- -. ., .

.. ...... I

-

I .

.....

... ..... . I . . .. .

-:.= I .1. .. - ? X.X

? 6% : ::: R .. .w . . . . . . , - . : XX.. x , .. ......... ..... , .. . .-- .- R :. : I : a .....I.,

..: .... ........... %, 1.

:::.:v7:.

:. - ? . .. I

...... . . . . . ??m

.. .:?? ? . I .w n

-

4 1 ? %%?,.??:?:... . ? , ? . .. ...... . x, .11. ? . 11

'.. .

..

.....

w -

-

I

.ii:

.W

. '.

....

?,gp. ..?

NO ll',?

.. ..- - '. .

xllmmm:..

... -.. - ,,.? .

W.M .,M

....

::,?,

-, W - - ...

....

?::?:Xy-:: ..,-. .11 - ..

T

, ... . ... .

.P. 1?:.? :::v ::-m:::m .l W ... ? ... ?

.. I .. ..

.

.- - ... ... ? I

.1 ... - ,:.... .. ? ... ? . .. ?. . 1. .. - . M ?

.. ..... I --...::: I M

I M E I .?- I

. .

u ?a.,.? - :, ? . ... 1.

I., ...

.

..

I

- ? -,-- --:

- ,??a,, ?' : .. :r,::. . -..:-:,. I ...... I ... 1. - ,

v:??: .: M

?

I

I R ...'....... ..... ..

7%...Q

.

?, ,:.:?.: ?

........

.

. . I. ... ...... ..- ... .

....

. ..... .1.1'... - . ::::k :? . .... . ......... .. . ?I?v

..

- . ? :

::::: I

.-

..... I.....

I

-

.3

..... ..... -

? ......... .:::?:.:.:.

..

?:?

.- . ", ?

? III - ... ??...- -- W. .W U ;?:.

... ,.

?...,

. . .

x: .? ...

4a :..:??* . . :::: . *: .?.. .P :,]i? ",:*: . . % 3 ?: ??:.::: lll- .Io. . I ..

.

?v :: . .

1- ?. .. % . I

...

.. g . , .j

-1 '... '. ,?",.x.`,:*: ? . . .

.

....... ..

. . . ?

- .........l. I., .... &. , 4.. ?::?, ?? ?::?: . :?.::??- :, ??-

.-.....

.1 ... -..- ez ? ... - ?:.?:.:.:.:.:,x:?.

,

- - ?. 1

?.- ..

A

.

FIGURE 7. Bust

Reliquary of

Saint Yrieix

(as

in

Fig. 6),

the wooden core, New York, Metropolitan

Museum

of

Art

(photo: Metropolitan

Museum

of Art, New

York).

13

reliquaries

before the 1990s-is Ilene

Forsyth's

Throne

of

Wisdom, published

in 1972.33

Long recognized

as a classic

study

of

Romanesque

carved

wood

images

of the

Virgin

and

Child, Forsyth's

book is ex-

tremely important

to the

study

of

body-part reliquaries

for

two reasons.

First,

it refutes Harald Keller's assertion that these

reliquaries

were created as the first

halting

and

incomplete

efforts of

sculptors

of limited

ability. Second,

it treats such

reliquaries

as a

genre

of

sculpture

with its own distinctive

aesthetic-manifest in the hieratic

quality

of the

figures,

their

otherworldly mien,

the use of

precious

metal and stones. For-

syth

notes the

disregard

in which

objects

like the bust of Saint

Baudime had been held

by

earlier scholars:

Considered the Christian 'idols' of the

Early

Middle

Ages,

they

have been

thought

more

pertinent

to a

study

of reli-

gion

than to a serious

history

of

sculpture.

It has been

difficult for art historians to realize that

sculptures

en-

dowed

by

the boundless medieval

imagination

with the

power

to

speak,

to

weep,

to

fly

out of

windows,

to

bring

rain in time of

drought,

to deter invaders in time of

war,

or

simply

to box the ears of the

naughty, might

also have

aesthetic merit.24

Body-part reliquary images, by

virtue of their

style

and/or

their

materials,

often fall outside the canons we have con-

structed for the art of Greece and Rome or of the Renaissance.

Even for medievalists,

their revetment with

precious

materials

distances them from the now colorless and

consequently

dis-

passionate

limestone of the

portal figures

of Gothic cathedrals.

The insistent

presence

of these

reliquary objects

is

frankly

unsettling.

This

distinctive,

affective aesthetic,

articulated

by

For-

syth,

was the focus of Ellert Dahl's

study

of the

Majesty

of

Saint

Foy.35

But while

Forsyth's apologia

for

Romanesque

images

was

accepted

for the

polychromed

wood

sculptures

of

the

Auvergne,

her discussion of the

larger

context of cult im-

ages

did not win

many

converts. Catholicism's insistence on

the

importance

of the

image

has

long

been

perceived by

some

(including

some

Catholics)

as

pagan, "primitive," "popular,"

and therefore anti-intellectual. This was the

argument

that

Bernard of

Angers

set out in his discussion of

image reliquar-

ies.36 This was the belief of Protestant Reformers on the

Continent and in

England-elitists

of the Word, as Margaret

Miles37 has described them-who mocked and decried the

importance

of relics, even in

rhyme:

The blessed arm of sweet Saint Sunday:

And whosoever

is blessed with this right hand, Cannot speed

amiss by

sea

nor by

land. And if he offereth eke with good devotion,

He shall not fail to come to high promotion.

And another

holy

relic here may ye

see: The great toe of the Holy

Trinity...

.38

This was the

argument

of

Platonists,

and of the French Rev-

olution,

when churches were rechristened

Temples

of

Reason,

and of French intellectuals to the

present day,

as elucidated

by

Martin

Jay.39

While other kinds of medieval

sculpture

can

be

(and

often

are)

dissociated from their

original religious

context,

and thus can be

analyzed formally-for

their rela-

tion to its

supporting column,

for

contrapposto,

for "natural-

ism" or

"realism"--medieval

reliquary sculpture

is

insistently

cultic. At their

very core, body-part reliquaries

have a direct

connection with a relic-with

something that,

but for the

"odeur de

sanctit6,"

would be associated with

decay

and

putrescence.

While Caroline

Bynum's pioneering

work in

examining

medieval attitudes about the

body

has shown the

rewarding

depth

of work for historians in this

area, body-part reliquaries

are

only

now

being

considered

seriously by

historians of art.

My

own interest in

pursuing

research on head

reliquaries,

considered

arguably

eccentric in

1986,

was awakened

by

the

experience

of

working

in a museum context and

by

the

sup-

port

of a French

advisor,

Danielle

Gaborit-Chopin.

Since that

time the involvement of art historians with

European training

in issues that relate to the cult of relics has

paved

the

way

for

more widespread investigation

of

reliquary sculpture.

David

Freedberg's

Power

oflmages

has lent

legitimacy

to works that

provoke

an intense

response.40

Hans

Belting's

work has been

critical in

opening up

lines of research into works

produced

in the so-called "era before art."4'

And

yet, body-part reliquaries

are still too often deemed

chiefly,

as Emile Male

declared,

"to offer the

perfume

of the

past."

This "scent" can too

easily

infect scholars

today.

Mi-

chael

Camille,

in his review of Hans

Belting's

Bild

und

Kult,

confesses to a fascination with

images,

born of what he con-

sidered an

extraordinary experience

of

witnessing

a devout

woman's efforts to

expel

demons from her

daughter by bang-

ing

the child's head

against

an

image.42

And in The Gothic

Idol he marvels at the

qualities

of head

reliquaries by musing:

"Head

reliquaries

are in fact rather

disturbing, decapitated

objects."43

Has the recent

study

of

body-part reliquaries

in the Mid-

dle

Ages emerged

almost as a

parallel

to the interest in

study-

ing

third-world or

"primitive"

cultures and their

religious

practices?

In recent

years

these have

given

birth to an exhi-

bition entitled Le Crane:

objet

de culte, objet d'art,

held in

Marseille in 1972, and Heads and Skulls in Human Culture

and History,

in 1991, which, while held at the Malaysian

Na-

tional Museum was nevertheless reviewed in the Wall Street

Journal, under the headline "An Exhibition that will really

turn heads."44 The National Museum of Anthropology

in Mex-

ico City

mounted an exhibition, Human Body,

Human Spirit,

exploring

"human figures made in ritual circumstances for

ritual purposes."45

There is, at

present,

a keen, almost voyeuristic

interest in

"dismemberment" during

the Middle Ages.

But the creation

14

of

body-part reliquaries

should not be

perceived

as a deli-

ciously gruesome

and

gory aspect

of the medieval cult of

saints. The

placement

of a skull or other relic in its container

was

part

of a solemn

ceremony:

the account of the

discovery

of the relics of Saint Privatus of Mende, their veneration, and

their

placement

in

reliquaries

is

typical

in

emphasizing

the

reverence of the

bishop

and the

congregation,

the

importance

of the

bishop's

sermon

concerning

the saint's life and the

healing power

of the

relics.46

A decision to isolate the skull

as a relic was not

dependent

on the saint's death

by decapi-

tation. Nor was the division of relics into other

body-shaped

reliquaries

a function of a saint's tortured dismemberment.

The

subsequent

veneration of the relic was

equally

reveren-

tial in nature: the

fourteenth-century

account of the venera-

tion of the head of Saint Martial at

Limoges specifies

that

pilgrims

went to the "altar of the head" as the monks

sang

the

Te Deum and

rang

bells. There

they wept

and

proclaimed

their thanks to the saint before a crowd of witnesses before

proceeding

to the

sepulcher

in the

crypt.47

We should be concerned about a method that

may

reduce

works of art to mere

sociological

curiosities. It is

not,

or

should not

be,

our final

goal

as art historians to tell

amusing

stories about the church of the Middle

Ages,

its beliefs or

practices.

It is

only

the

beginning

of our homework to know

the catechism of faith

through

the course of the Middle

Ages.

We must

applaud

the

publication

of the

legends

of the saints

in

English.48

It

is

instructive to document modern

processions

of

relics,

like those of Saint Yrieix

during

the Ostensions that

are held

every

seven

years

in the

Limousin,

to

suggest

the

continuing

tradition of the rites of the Middle

Ages.49

Fo-

cused

analysis

of the

context,

where it informs us about the

object,

is essential. In her

study

of the

treasury

of Trier Hil-

trud

Westermann-Angerhausen

was able to show

convincingly

that the so-called

Reliquary

Foot of Saint Andrew was in fact

a

portable altar; similarly,

in a

forthcoming publication

Joan

Holladay

has used

contemporary

church

history

to

explain

the choice of

polychromed

wood busts of Saint Ursula and

her

companions

and the manner of their decoration at Co-

logne.50

As

they

are in these

studies,

the links between con-

text and works of art must be

manifest;

historical research

that does

not, finally,

inform our

understanding

of the

object

is a

discipline

other than art

history: finding

out that Paul

Revere rode

through

the towns around Boston the 18th of

April

in '75

may

or

may

not tell us

anything about him as a

silversmith, and we are

obliged

as art historians to ask our-

selves if it does.

It is

important that we consider

body-part reliquaries as

part of the

history

of

images;

since

Forsyth

and

Belting,

such

an

argument

now seems self-evident. Still, a

large dosage

of

"old" art history must remain in the mix. The historian

Patrick

Geary, echoing

the words of Marc Bloch more than a

generation ago, has just recommended that historians use ar-

chaeology as part of their

body

of

evidence;51

art historians

themselves need to reaffirm their focus on visual evidence

and aesthetic issues. A linear evaluation of

stylistic develop-

ment

following

the tradition of the

analysis

of

Romanesque

or Gothic

sculpture

is not

possible, given

the now-limited

body

of

material,

nor what I would advocate. We must con-

tinue to

pay

attention to

questions

of

style

and

quality,

and of

attribution,

as

Pierluigi

Leone de Castris and Danielle Gaborit-

Chopin

have done in the case of the

silver-gilt, crystal

and

enamel arm

reliquaries

of Saint Louis of Toulouse and Saint

Luke in the Louvre

(Figs. 8, 9).52

Art historians need to examine how and where such rel-

iquaries

were conceived and executed.

Though

I have

ques-

tioned some

aspects

of their

conclusions,

the efforts of Jean

Hubert and Marie-Clotilde Hubert in

defining

the

geographic

distribution of

image reliquaries exemplify

the kind of seri-

ous historical research that needs to be done for

body-part

reliquaries.53

Studies of

patronage

will reveal a

great

deal about the

importance

of

body-part reliquaries

in the Middle

Ages.

The

reliquary

made for

Boson, king

of

Provence,

was not an iso-

lated

example.

The

fourteenth-century

head

reliquary

of Saint

Martial was made at

Avignon

as a

gift

of

Pope Gregory

XI to

his native diocese of

Limoges.54

The Duke of

Berry,

known

for his

manuscripts,

was also the

patron

of

richly jeweled

bust

and arm

reliquaries bearing

his coat of arms.55

We need to consider how the

appearance

of these reli-

quaries

related to their function. How did

reliquaries

in the

form of

bodily parts

differ in function and/or material from

sarcophagus-shaped

chasses? In the Massif

Central,

for ex-

ample, image reliquaries

of

precious

materials that could be

carried about were created to contain the skull of the

saint,

while other

bodily

relics were

placed

in a chasse for venera-

tion at the tomb. How often can one see a

hierarchy

of rel-

ics

suggested by

the materials used to contain different

parts

of the

body,

as at Saint-Nectaire in the

Auvergne

in the fif-

teenth

century? There,

in

1488, Antoine, "seigneur

de Saint-

Nectaire,"

ordered the fabrication of a silver bust for the head

of Saint

Nectaire,

a silver

arm,

a

crystal ampulla

enclosed in

silver for the

heart,

a

copper

chasse for the rest of the

body

and a wood box for

"Aliqua parva

ossa beati Necterii et terra

quae

fuit

reperta

infra tumulum."56 At

Bourges,

the existence

of a series of

silver-gilt

arm

reliquaries

of the cathedral's

sainted bishops appears

to

present thematic

analogies

to the

images

of the

bishops

in stained

glass.57

It is essential to consider how these works were viewed in

aesthetic terms in the Middle

Ages.

It matters that the eleventh-

century description

of the head

reliquary

of Saint Valerien

at Tournus called it "a comely image

of

gold

and most

pre-

cious

gems

in the likeness to a certain

point,

of the

martyr,"'5

and that Bernard of

Angers referred to the "animated, lively

expression"

of the

image

of Saint Geraud at Aurillac.59 Texts

like these remind us that a head like the one of Saint Yrieix

is not meant to be seen as a wooden core, but as a luminous,

15

:: ::: ::: :: :

_ii

m

. . ... . .. . .. .......

...: . .. :

iiiiiiiiii ii

ii iiiii iiiii iiiii

iiiiiiiiil

iiiiiiiiiiiii~~iii!iiii~i~iiiiiiiiiiiill iii~~i~iixiim.

FIGURE 8. Arm

Reliquary of

Saint Louis

of Toulouse, 1337-38, musee du

Louvre, Paris

(photo: Courtesy of

the musee du Louvre).

luxurious

presence

that was a likeness "to a certain

point,

of

the

martyr,"

and that it was considered beautiful. At the end

of the thirteenth

century,

it mattered that the head

reliquary

of France's

royal

Saint Louis resemble the head

reliquary

of

Saint Denis in

appearance

and construction-that the visual

metaphor

served to link the saints.60

The

images

on seal

matrices,

and on

pilgrim badges,

such as those of Thomas

Becket,

Saint

Quentin,61

Saint Julien

of Le

Mans,62 or those, perhaps

of Saint

Denis, recently

ex-

cavated at Saint-Denis should be looked at more

thoroughly

in relation to

descriptions

of lost

reliquaries. Images

in other

media

may

further inform us

concerning

the form and

usage

of

body-part reliquaries.

For

example,

an

image

of the relic of

AMON&~

......

ICA*:

FIGURE 9. Arm

Reliquary of

Saint Luke, ca. 1337-38, musee du Louvre,

Paris

(photo: Courtesy of

the musee du

Louvre).

Saint

Philip resembling

a head

reliquary appears

in the ca-

thedral

glazing

of the choir of the cathedral of

Troyes,

which

acquired

the head after the sack of

Constantinople.63

Additional texts should be scoured for references to

body-

part reliquaries.64

Such texts can be related to what we know

from

surviving objects

and

provide

a broader

picture

of the

kinds of

reliquaries produced

in

particular

centers of

gold-

smithwork at

particular periods.

For

example,

the

silver-gilt

head of Saint

Stephen

of Muret from the Grandmont

Treasury

has been considered since the time of

Rupin

as

part

of the

Oeuvre de

Limoges.65 Yet,

with its

heavily

individualized fea-

tures,

it seems anomalous in the context of Limousin metal-

work.

Early descriptions

indicate that it once had enameled

16

... ..... .....

. ........ . .

.......

ol

FIGURE 10. Bust

Reliquary of

San Gennaro, 1304-6, Treasury of

the Ca-

thedral

of

San Gennaro, Naples (photo: after

Leone de Castris, 1986).

scenes of the life of the saint around the base. This de-

scription, plus

the fact that it once bore the arms of

Cardinal

Brissonet, suggests

that it should rather be considered in the

context of Italian

examples,

such as the one of Saint John

Gualbert at

Passignano.66

Successive inventories of a

single treasury

can offer in-

sights

into the

varying

uses and

changing

forms of

reliquaries

in a

particular

location.

Eight surviving inventories, ranging

in date from 1396 to

1791, plus

a number of documents

sug-

gest changing patterns

of veneration at Mont-Saint-Michel.

The

body

of Saint

Aubert,

a saint whose

origins

are obscure

but whose

body

was

preserved

at the

abbey,

was enshrined in

a

chasse;

a

separate reliquary

for his skull was made in 1131.

As with other recorded

examples

from the north of France be-

fore the second

quarter

of the thirteenth

century,

this twelfth-

century reliquary

for the head was not in bust

form,67

but

rather

dome-shaped.

A

separate

arm

reliquary

of Saint Aubert

was first fabricated in

1477;68

the

inventory specifies

that it

was used for the

swearing

of oaths. The

patron

of the arm rel-

iquary, prior

Oudin

Bou~tte,

also had a new chasse made for

the

body.

While the

reliquary

for the skull of Saint Aubert

was

apparently

not

replaced,

a new

bust-shaped silver-gilt

reliquary

was fabricated at the same time for the head of

Saint Innocent.69 There were also

arm-shaped reliquaries

for

relics

brought

to Mont-Saint-Michel from abroad: the "osse-

ment du bras" of Saint

Lawrence, brought

to the

monastery

from Rome in 1165. There were also

reliquaries

for the arms

of female saints-an arm of

Mary

"la bienheureuse

Egypti-

enne" recorded in

1396,

and a

single arm-shaped reliquary

containing

an arm of the

virgin martyr

saint

Agnes

and one of

Agatha.70

Each of these three was

necessarily

an

exception

to

the standardized

image

of an arm with its

right

hand

gestur-

ing

in

priestly blessing.

While we consider the evidence of lost

treasures,

we

must likewise turn our attentions to

great

works of art that

have not been

adequately studied,

of which the bust of San

Gennaro in the

treasury

of his titular church at

Naples,

made

by

French

goldsmiths,71

and the head of Saint

Agatha

in the

treasury

of Catania are but two

examples (Figs. 10,

5).72

It

is

only through

such

probing study

of individual

problems

that

a more

complete

sense of the whole will

emerge.

If we con-

sider Braun as our Arthur

Kingsley Porter, laying

out the cor-

pus

of

reliquary sculpture,

it is time to

get

on with focused

studies of individual works and of the

production

of

particu-

lar

periods

and

regions. Only

then can we

approach any

kind

of

encyclopedic understanding

of medieval

body-part

reli-

quary sculpture,

over the

long

course of the Middle

Ages

and

throughout

Western

Europe.

NOTES

1. The CD-Rom for the BHA

(Bibliographie

de

l'histoire

de

l'art)

in-

cludes over 200 entries under the

subject

of

reliquaries

for the

years

1990-1995.

2. S. Beissel,

Die

Verehrung

der

Heilige

und ihrer

Reliquien

in Deutsch-

land bis zum Beginne

des 13. Jahrhunderts, Ergainzungshefte

zu den

Stimmen aus Maria-Laach,

47

(Freiburg

im

Breisgau, 1890, reprinted

Darmstadt, 1983).

3. See H.

Delehaye,

L'Oeuvre des Bollandistes a travers trois siecles,

Subsidia

hagiographica 13a.2,

2nd ed.

(Brussels, 1958).

4. The container sometimes belies the contents.

During

a

trip

to Rome,

Abbot Gauzlin of

Fleury (1004-1030) purchased

a

golden

arm in which

he

placed,

not an arm bone,

but a relic of the shroud of Christ. See

Andre de

Fleury,

Vita Gauzlini abbatisfloiracensis

monasterii.

(Vie

de

Gauzlin,

Abbe de

Fleury),

ed. and trans. R.-H. Bautier and G.

Labory

(Paris, 1969),

61-63.

5. See E. Kovics, Kopfreliquiare

des Mittelalters

(Budapest, 1964),

sur-

veying

and

illustrating forty-two examples;

B. Bessard,

II

Tesoro. Pel-

legrinaggio

ai

corpi

santi e

preziosi

della

cristianith (Milan, 1981),

and B. Falk, "Bildnisreliquiare.

Zur

Entstehung

und

Entwicklung

der

metallenen

Kopf-, Bdisten- und

Halbfigurenreliquiare

im Mittelalter,"

Aachener

Kunstblidtter,

LIX

(1991/93).

6. Abbe Texier, "Bras," Dictionnaire

d'orfrvrerie,

de

gravure

et de cise-

lure chretiennes... (Paris, 1857),

cols. 279-80.

7. See A. Bouillet and L.

Servibres,

Sainte

Foy, vierge

et

martyre (Rodez,

1990).

The authentication of the relics was

published

two

years

before:

Mgr. Bourret,

Procks-verbaux

authentiques

et autres

pieces

concernant

la reconnaissance des

reliques

de sainte

Foy, vierge

et

martyre (Rodez,

1888).

8. A. Bouillet and L.

Servieres,

Sainte

Foy, vierge

et

martyre, unpag-

inated prefatory

letter.

9. On Peiresc see La Grande

encyclopddie:

Inventaire

raisonnd

des sci-

ences, des lettres et des arts

(Paris, 1885-1900), XXVI, 256; J. B. Re-

quier,

Vie de Nicolas-Claude-Peiresc (Paris, 1770).

17

10. Six volumes of Peiresc's letters were included in M.

Tamizey

de Lar-

roque,

Collection des documents inidits sur

l'histoire

de France.

11. E. Kovics, "Le chef de Saint Maurice a la cathedrale de Vienne

(France),"

Cahiers de civilisation

mdie'vale, VII

(1964),

19-26.

12. A.

d'Auvergne,

"Notice sur le Buste de saint Baudime conserve dans

l'6glise

de Saint-Nectaire

(Puy-de-Dome),"

Revue des societis

savantes,

ser. 2, 1

(1859),

1-4.

13. "Dans tous les

reliquaires qui

viennent de

passer

sous nos

yeux,

on

placait

des

corps

entiers ou des

parcelles

de

corps,

ou bien des

objets,

comme des

v&tements, qui

avaient

appartenu

aux bienheureux en l'hon-

neur

desquels

ces

reliquaires

6taient

executes. Mais il arrivait

souvent,

quand

on

possedait

une

partie

determinre

du

corpus

d'un

saint, qu'on

faisait un

reliquaire

de form

speciale pouvant representer

aux

yeux, par

l'enveloppe

exterieure, la form de

l'objet

contenu dans cette

enveloppe

meme." E. Rupin,

L'Oeuvre de

Limoges (Paris

and Brieve, 1890),

447.

14. E. Rupin,

"Chef de Saint Martin en

argent

dora et

6maill6

XIe siecle,

Eglise

de Soudeilles

(Correze),"

Bulletin de la socite' scientifique,

his-

torique

et

archdologique

de la Correze, IV

(1882),

435-56.

15. On

Morgan

as a collector of medieval

art,

see W. D. Wixom, "J. Pier-

pont Morgan:

The Man and The

Collector,"

in

Migration

Period Art in

The

Metropolitan

Museum

of Art, 3rd-8th

Century: Highlights from

the J.

Pierpont Morgan

Collection and Related Material Reconsid-

ered, papers

of the

symposium

held

May 22-23, 1995, forthcoming.

16. Les tresors des

iglises

de France, exhibition at the Musee des arts

decoratifs, Paris, 1965.

17. W. D.

Wixom, Treasures from

Medieval France, exhibition at the Cleve-

land Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio, 1967. See no. VII, 13, Bust rel-

iquary

of Saint Felicule from

Saint-Jean-d'Aulps (Haute-Savoie),

late

fifteenth

century.

18. H. Keller, "Zur

Entstehung

der sakralen

Vollskullptur

in der ottoni-

schen Zeit," in

Festschriftfiir

Hans Jantzen (Berlin, 1951), 71-90.

19. R. RUckert, "Beitrdige

zur limousiner Plastik des 13. Jahrhunderts,"

ZfK,

XXII

(1959),

1-16.

Rtickert

also

published

an article on the

Byz-

antine

reliquaries

for the skulls of

saints, which

traditionally

do not as-

sume the form of a human head or bust. See R.

Riickert,

"Zur Form der

byzantinischen Reliquie,"

Miinchener Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst,

VIII

(1957),

7-36.

20. E Souchal, "Les Bustes

reliquaires

et la

sculpture," Gb-a,

LXVII

(1966),

205-15.

21. W. D. Wixom, Treasures of

Medieval France, 318.

22. I. Lavin, "On the Sources and

Meaning

of the Renaissance Portrait

Bust," The Art

Quarterly,

XXXIII

(Autumn 1970),

207-26.

23. A. Moskowitz, "Donatello's

Reliquary

Bust of Saint Rossore," AB,

LXIII

(1981),

41-48.

24. The four

reliquaries

are accession numbers 17.190.728, 59.70, 67.155.23

and 1976.89. They are now exhibited in a chapel-like setting at The

Cloisters. They are discussed in terms of their original context in W. D.

Wixom, "Medieval Sculpture at The Cloisters," The Metropolitan Mu-

seum of Art Bulletin, XLVI/3 (Winter 1988/89), 40-41.

25. P. Pieper, "Der goldene Pauluskopf des Domes zu MUnster," in Studien

zur Buchmalerei und Goldschmiedekunst des Mittelalters. Festschriftfiir

Karl Hermann Usener zum 60. Geburtstag am 19. August 1965 (Mar-

burg an der Lahn, 1967), 33-40.

26. "Das Kopfreliquiar des heiligen Candidus in St-Maurice," Zeitschrift

fiir

schweizerische Archiologie und Kunstgeschichte, XXIV/2 (1965/

66), 65-127.

27.

TP. E Hoving, "The Face of St. Juliana," The Bulletin of The Metro-

politan Museum ofArt, NS XXI (1963), 173-81.

28. P

Williamson, The

Thyssen-Bornemisza

Collection: Medieval

Sculp-

ture and Works

of

Art

(London

and New

York, 1987), 98-103, no. 18.

29. The

images

of these

destroyed

bust

reliquaries

are illustrated in D.

Gaborit-Chopin, Regalia:

Les Instruments du sacre des rois de France

(Paris, 1987), 57, figs.

7-8.

30. See E Rossi, Capolavori

di

orefeceria

italiana dall'XI al XVIII secolo

(Milan, 1956), 9, fig.

3.

31. For the

finger-shaped reliquary

of John the

Baptist

held

by

the saint,

see

Tresors des

iglises,

cat. 168, pl. 149; for the

thigh

at Saint-Gilad-

de-Rhuys,

see cat. 331, pl.

167.

32. The Cloisters, for

example,

as

originally conceived, had no

treasury

for

precious objects.

33. I. H.

Forsyth,

The Throne

of

Wisdom: Wood

Sculptures of

the Ma-

donna in

Romanesque

France

(Princeton, 1972).

34. Ibid., 3.

35. See E. Dahl, "Heavenly Images:

The Statue of St.

Foy

of

Conques

and

the

signification

of the Medieval

'Cult-Image'

in the West," Acta ad

Archaeologia

etArtium Historiam

Pertinenta, VIII

(1987),

175-91. The

emphasis

on this

aspect

of

images

was

repeated by

A. G.

Remensnyder,

"Un

probleme

de cultures ou de culture?: La

statue-reliquaire

et les

joca

de sainte

Foy

de

Conques

dans le Liber miraculorum de Bernard

d'Angers,"

Cahiers de civilisation

midievale, XXXIII

(1990),

351-79.

36. Bernard of

Angers,

"Liber miraculorum S. Fidis," J.-P

Migne, ed., PL,

CLXI, 127-64.

37. See M.

Miles, Image

as

Insight (Boston, 1985).

38. See J.

Phillips,

The

Reformation of Images:

Destruction

of

Art in En-

gland,

1535-1660

(Berkeley,

Los

Angeles

and London, 1973),

19.

39. M.

Jay,

Downcast

Eyes:

The

Denigration of

Vision in

Twentieth-Century

French

Thought (Berkeley, 1993).

40. D.

Freedberg,

The Power

of Images:

Studies in the

History

and

Theory

of Response (Chicago, 1989).

41. His discussion of the bust

reliquary

of Saint Martial

(actually

four suc-

cessive heads and

busts)

at

Limoges is, however,

an

inadequate

re-

hearsal of the literature. The first recorded

image

was fabricated after

952; the second was made

by 1206; the third was new in 1307; the

fourth was created between 1370-1380 for

Pope Gregory

XI. See B. D.

Boehm, "Medieval Head

Reliquaries

of the Massif Central"

(Univer-

sity Microfilms,

Ann Arbor, Mich., 1990),

322-28.

42. M. Camille, review of H.

Belting,

Bild und Kult: Eine Geschichte des

Bildes vor dem Zeitalter der Kunst

(Munich, 1990), AB,

LXXIV

(1992),

514.

43. M. Camille, The Gothic Idol.

Ideology

and

Image-Making

in Medieval

Art

(Cambridge, 1989),

279.

44. The article

by

John D.

Wagner

was

published

on

August 20, 1991,

p. A12.

45. From the flyer from the University of Pennsylvania Press for C. E.

Tate, ed., Human Body, Human Spirit, A Portrait of Ancient Mexico,

first published in 1993.

46. See C. Brunel, Les Miracles de Saint Privat, suivis des opuscules d'Al-

debert III, eveque de Mende (Paris 1912), 59-74.

47. See E Arbellot, "Miracula S. Martialis Anno 1388," Analecta Bollan-

diana,

I

(1882), 411-45.

48. A model in this regard is Pamela Sheingorn, ed., The Book of Sainte

Foy (Philadelphia, 1995).

49. See E Lautman, "Ostensions et identitis limousines," in L~gende dorde

du Limousin: les saints de la Haute-Vienne (Limoges, 1993), 78-89.

18

The

exhibition,

held at the Musee de

Luxembourg

in Paris in

1993-94,

included a number of medieval

reliquaries

of

exceptionally

fine

quality

and

importance.

Because the exhibition's focus was on the broader

topic