Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Metacognition and Learning in Adulthood

Transféré par

Duval PearsonDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Metacognition and Learning in Adulthood

Transféré par

Duval PearsonDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Metacognition and learning in adulthood

Prepared in response to tasking from ODNI/CHCO/IC Leadership Development Office by Dr. Theo L. Dawson , Developmental Testing Service, LLC

1

Saturday, August 23, 2008

35 South Park Terrace, Northampton, MA 01060

T Phone F Phone

Email http:devtestservice.com

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Metacognition and learning in adulthood

Contents

Metacognition

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Metacognition and learning in adulthood 1

What is metacognition?

Metacognition is thinking about thinking. Metacognitive skills are usually conceptualized as an interrelated set of competencies for learning and thinking, and include many of the skills required for active learning, critical thinking, reflective judgment, problem solving, and decision-making. Adults whose metacognitive skills are well developed are better problem-solvers, decision makers and critical thinkers, are more able and more motivated to learn, and are more likely to be able to regulate their emotions (even in difficult situations), handle complexity, and cope with conflict. Although metacognitive skills, once they are well-learned, can become habits of mind that are applied in a wide variety of contexts, it is important for even the most advanced adult learners to flex their cognitive muscles by consciously applying appropriate metacognitive skills to new knowledge and in new situations. According to Flavell (1979), who coined the term, metacognition is a regulatory system that includes (a) knowledge, (b) experiences, (c) goals, and (d) strategies. Metacognitive knowledge is stored knowledge or beliefs about (1) oneself and others as cognitive agents, (2) tasks, (3) actions or strategies, and (4) how all these interact to affect the outcome of any intellectual undertaking. Metacognitive experiences are conscious cognitive or affective experiences that concern any aspect of an intellectual undertaking. Knowledge is considered to be metacognitive (as opposed to simply cognitive) if it is used in a strategic manner to meet a goal. According to Sternberg {, 1986 #14899) it is "figuring out how to do a particular task or set of tasks, and then making sure that the task or set of tasks are done correctly" (p. 24). Some of the concepts commonly associated with the metacognition literature are shown in Table 1.

Theo L. Dawson, Ph.D. (UC Berkeley, 1998), is a respected cognitive developmental psychologist. Her work focuses

on the description of learning sequencesthe actual pathways through which people learn complex concepts and skillsand the design of developmental assessments of these skills. She has worked closely with members of the IC since 2002, when she, along with her colleague Dr. Kurt Fischer (Harvard Graduate School of Education), conducted a study of the sequences through which critical thinking, leadership reasoning, and decision making skills develop in adulthood. Since then, her work with the IC has involved assisting with the design of leadership curricula, evaluating the extent to which curricula support leader development, and helping to define skill levels for a range of leadership and analyst standards. Metacognition 3

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Table 1: Metacognition concepts

Concept Metacognitive knowledge about persons Metacognitive knowledge about tasks Metacognitive knowledge about strategies Level of conscious awareness of metacognitive knowledge Limits of metacognitive knowledge Duration of metacognitive experiences Occurrence of metacognitive experiences Effects of metacognitive experiences Memory-monitoring, selfregulation, meta-reasoning, consciousness/awareness, and autoconsciousness/selfawareness Transfer Cognition Ill-structured problems Description Includes a persons beliefs about intra-individual differences, inter-individual differences, and universals of cognition The information available to apply to a cognitive activity and an individuals knowledge about the task demands of a given situation Awareness of and beliefs about available strategies Retrieval and construction of metacognitive knowledge can be either conscious or unconscious Can be accurate or inaccurate, may not be activated when needed, may not have much influence when it is activated, and may not have a beneficial effect when it is influential Can be momentary or lengthy, as when we are consciously grappling with a challenging problem Most likely to occur when one is engaged in intentional, reflective intellectual activities such as problem-solving and learning Can lead one to establish new goals and to revise or abandon old ones, can cause one to add to ones existing metacognitive knowledge base, and can activate strategies that would otherwise have remained inactivated Other terms for metacognition

Using a metacognitive skill learned in one context to solve a problem in another context. A general term for thinking, sometimes distinguished from metacognition, which is thinking about thinking. Ill-structured problems are open-ended, with unclear goals, multiple solutions, and no right answerslike many of the problems we face in the workplace

Double loop learning

Learning how the way one defines and solves problems can be a source of problems (Argyris, 1991).

Models of metacognition

The term metacognition is both a general term for thinking about thinking, and a term used by a particular group of researchers to describe their field. There are numerous models of metacognition, far too many to describe here. To complicate things further, metacognition is a central component of several skill sets that are central to education and the workplace, including (1) reflective judgment, (2) critical thinking, (3) decision making, and (4) problem solving. (Some researchers argue that these are components of metacognition.) Table 1 provides brief descriptions of some of the more prominent metacognitive models.

Metacognition

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Table 2: Models of metacognition

Finding Self regulated learning (lower levels) Implication Reference (J. G. Borkowski & Thorpe, 1994; Como, 1986; Ghatala, 1986; Schloemer & Brenan, 2006; Barry J. Zimmerman, 1990) Note: Watch out for applications of this model that focus exclusively on teaching students more effective ways to memorize facts.

Self-regulated learners approach educational tasks with confidence, diligence, and resourcefulness; are aware when they know a fact or possess a skill and when they do not; proactively seek out information when needed and take the necessary steps to master it; find a way to succeed even when they encounter obstructions; view learning as a systematic and controllable process; accept responsibility for their achievement outcomes; and monitor the effectiveness of their learning methods or strategies. Self-regulated learning strategies include self-evaluation, organization and transformation, goal setting and planning, information seeking, record keeping, self-monitoring, environmental structuring, giving self-consequences, rehearsing and memorizing, seeking social assistance, and reviewing. (paraphrased from Zimmerman, 1990) In addition to metacognition, motivation and behavior are considered to be components of self-regulated learning.

Metacognition

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Finding Critical thinking (all levels)

Implication

Reference The Foundation for Critical Thinking (http://criticalthinking.org) This model includes standards of thought (clarity, accuracy, relevance, logicalness, breadth, precision, significance, completeness, fairness, and depth), which are applied to the elements of thought (shown on the left), resulting in the development of intellectual virtues. This is an iterative cycle, which is repeated as reasoning increases in complexity over the course of development. Critical thinking and creative thought are linked in this model (Paul & Elder, 2006).

Reflective judgment Double loop learning (upper levels)

The reflective judgment model is a very well-researched model of the development of thinking about thinking. Argyris brings metacognition to the workplace by highlighting the importance of becoming conscious of the consequences of ones actions. He uses real-life examples from the workplace to demonstrate methods for teaching upper level managers to think effectively about their thinking.

(Kitchener & Fischer, 1990; Kitchener & King, 1990; P. K. Wood, 1997) {Argyris, 1991 #14906; Argyris, 1982 #14625;

Metacognition

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Metacognition research

Table 3: Metacognition and learning

Finding Metacognitive skills develop. Implication They can be learned. Reference (Baer, Hollenstein, Hofstetter, Fuchs, & Reber-Wyss, 1994; Brown, Bransford, Ferrara, & Campione, 1983; John H. Flavell, 1979; Ruth Garner & Alexander, 1989) (J. H. Flavell, 1981; Ruth Garner & Alexander, 1989; Glenberg, Wilkinson, & Epstein, 1982) (J. Borkowski, Carr, & Pressely, 1987; Bransford, Sherwood, Vye, & Rieser, 1986; Carr, Kurtz, Schneider, Turner, & Borkowski, 1989; R. Garner, 1990; Hascher & Oser, 1995; Mace, Belfiore, & Hutchinson, 2001; Pressley & Ghatala, 1990; B. J. Zimmerman & Schunk, 2001) (Bransford et al., 1986; EwellKumar, 1999; Heath, 1983)

Adults often fail to monitor their thinking. Students who have been taught metacognitive (self-regulated learning) skills learn better than students who have not been taught these skills.

Adults can benefit from metacognitive training. It is possible to produce better learners by teaching metacognitive skills.

Students with good metacognitive skills are better critical thinkers, problem-solvers, or decision makers than students who are not. People whose thinking is more complex tend to have better metacognitive skills. In most people, the development of cognitive complexity progresses at different rates in different knowledge domains, depending upon experience and learning in particular domains. Cognitive development involves both knowledge acquisition and (largely unconscious) knowledge structuring. (If there is no knowledge to organize, then there is no development.) Content knowledge is more easily accessed in real-world situations if students learn how new concepts and procedures can function as tools for solving relevant problems. Both content knowledge and metacognitive skills are essential for learning.

It is possible to produce better critical thinkers, problem-solvers, and decision makers by teaching metacognitive skills. Metacognition and cognitive complexity are related. Since cognitive complexity and metacognition are related, we might expect metacognition to be more advanced in more developed knowledge domains. Because metacognitive skills involve the conscious structuring of knowledge, they are likely to be more developed in areas of greater knowledge. Learning environments should include opportunities for students to reflectively apply new concepts and tools in real-world contexts. Learning may be enhanced when instruction (1) provides explicit content knowledge while (2) asking students to use metacognitive skills to operate on that knowledge. Increased self-confidence and a sense of increased personal responsibility may provide motivation for learning.

(Swanson & Hill, 1993; Vukman, 2005) (Fischer & Pruyne; Fischer, Yan, & Stewart)

(Bransford et al., 1986)

(Glaser, 1984)

(Bransford et al., 1986; Perkins, 1987)

Metacognitive training can increase students self-confidence and sense of personal responsibility for their own development.

(McCombs & Marzano, 1990; Schunk, 1990)

Metacognition

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Finding Metacognitive training can increase students motivation to learn.

Implication Training in metacognitive skills may enhance students sense of self efficacy, thus increasing their motivation to learn. Metacognitive strategies should be embedded in assignments and classroom activities across the curriculum at every level of instruction

Reference (Bandura, 1986; Hofer & Yu, 2003; Sperling, Howard, Staley, & DuBois, 2004) (Ruth Garner & Alexander, 1989)

Moving adult learners to a point of acknowledging that old routines no longer work as well as new, instructed ones takes time and many demonstrations of the superiority of the new routines. Intelligent novices can use general metacognitive skills to figure out how to obtain knowledge in an unfamiliar domain.

Once adults have gained expertise and learned how to use a range of metacognitive skills in one domain, they can use some of their metacognitive skills to more rapidly learn in another domain. Teachers or intelligent tutors can support the use of existing metacognitive strategies in new knowledge areas by providing feedback that reminds students to employ metacognitive strategies they have used in familiar knowledge areas. Classrooms in which covering the content is emphasized over understanding can deprive students of the opportunity to learn and master learning skills. Concept mapping, used well, is a useful metacognitive skill.

(Bruer, 1993; Mathan & Koedinger, 2005); Garner, 1989 #14918}

Students receiving intelligent novice feedback acquire a deeper conceptual understanding of domain principles and demonstrate better transfer and retention of skills over time than students who do not receive such feedback. When students perceive an emphasis on mastery goals in their classroom, they report using more metacognitive learning strategies. Use of concept maps helped adult students develop thinking skills, promoted growth in understanding their learning processes, and fostered understanding of knowledge construction. Repeated experiences of dyadic discussions within the classroom improved reasoning skills (over controls). Informal learning is enhanced in managers who employ a wide range of metacognitive strategies. Students in problem based learning classrooms have been found to have higher levels of intrinsic goal orientation, task value, use of elaboration learning strategies, critical thinking, metacognitive selfregulation, effort regulation, and/or peer learning compared with control-group students.

(Mathan & Koedinger, 2005)

(Ames & AfIher, 1988)

(Daley, 2002)

Active engagement in thinking about a topic enhances the quality of reasoning about that topic. Training in the use of metacognitive strategies may increase informal learning in less metacognitively sophisticated managers. Problem based learning environments may enhance metacognitive skills relative to conventional instructional environments.

(Kuhn, Shaw, & Felton, 1997)

(Enos, Kehrhahn, & Bell, 2003)

(Sungur & Tekkaya, 2006)

Metacognition

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Finding Gifted learners have been found to employ fewer metacognitive strategies than less gifted students.

Implication Gifted learners, because they learn easily, may not need to employ metacognitive strategies to excel. This could result in reasoning deficits in later life.

Reference (Dresel & Haugwitz, 2005)

Table 4: Metacognition and critical thinking

Concept Critical thinking is the ability to (1) identify and formulate important questions and problems; (2) gather and assess information; (3) test proposed conclusions against relevant criteria and standards; (4) think within alternative systems of thought, assessing their assumptions, implications and practical consequences; and (5) communicate effectively, without appealing to logical fallacies or manipulating others. Resources The Foundation for Critical Thinking (http://criticalthinking.org)

Table 5: Metacognition and reflective judgment

Description Reflective judgment is metacognition. Beliefs about learning significantly impact the quality of learning strategies and learning outcomes in general. Students whose reflective judgment skills are more developed are likely to be better learners. Implications Source (Hofer, 2004) (B. K. Hofer, 1999; Barbara K. Hofer, 2000; Paulsen & Feldman, 2005; Schommer, 1990, 1993; Schommer, Crouse, & Rhodes, 1992)(Brten & Stromso, 2005; Muis, 2007; P. Wood & Kardash, 2002)

Metacognition

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Figure 1: Model of metacognitive skills and conditions for their development and use

Metacognition

10

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Table 6: Metacognition and problem solving

Finding Effective problem solving depends on the nature and organization of the knowledge available to individuals. Psychological biases interfere with problem-solving Implications Students whose reasoning skills are more developed are likely to be better learners. Source Bransford, 1986 #6747; Chi, 1988 #982}

Psychological biases may be ameliorated through metacognition

(Duchon, Ashmos, & Dunegan, 1991)

Table 7: Metacognition and psychological biases

Unconscious knowledge structuring takes place every time we learn something. These natural structuring processes have limitations that (1) are ineffective in some situations or (2) produce cognitive biases. Metacognition can be employed to counter these biases. Note: Although it is clearly part of the subtext of much research in metacognition (especially critical thinking), the subject of psychological bias is rarely raised explicitly.

Bias Overestimate explanatory knowledge Implications People tend to overestimate the depth of their explanatory knowledge (how well they understand concepts), which can produce decision errors. Source (Mills & Keil, 2004)

Table 8: Metacognition and mindfulness

Finding or comment Mindfulness begins by bringing awareness to current experienceobserving and attending to the changing field of thoughts, feelings, and sensations from moment to momentby regulating the focus of attention. This leads to a feeling of being very alert to what is occurring in the here-and-now. It is often described as a feeling of being fully present and alive in the moment. (p. 232) Mindfulness is further defined by an orientation to experience that [involves] making a commitment to maintain an attitude of curiosity about where the mind wanders. (p. 233) Mindfulness can be thought of as creating an optimally receptive state for new learning and experience, increasing the likelihood that appropriate metacognitive skils will be selected and employed. Mindfulness practice requires the activation of metacognitive knowledge, monitoring, and control. Source (Bishop et al., 2004)

(Garland, 2007; Thomas, 2006) (Wells, 2005)

Metacognition

11

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Figure 2: Metacognitive skills are an important component of interpersonal intelligence

Metacognition

12

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Teaching and learning metacognition

Figure 3: Learning model for the workplace, emphasizing motivation, assessment, and metacognition (adapted from http://www.bbi.school.nz/philosophy/learningtolearn.html)

Table 9: Teaching and learning metacognitive skills: The research

Finding Metacognitive skills can be taught. Reference (J. Borkowski et al., 1987; Bransford et al., 1986; R. Garner, 1990; Hascher & Oser, 1995) (Ericsson, Chase, & Faloon, 1980)

Metacognitive skills learned in one context are not automatically transferred to another context.

Metacognitive skills are learned and applied more effectively in supported active learning contexts than in direct instruction contexts. An application of metacognition to diversity issues. Could be useful as a starting place for discussion. The role of formative assessment in self-regulated learning. (Byars-Winston & Fouad, 2006) (Nicol & MacFarlaneDick, 2006)

Metacognition

13

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Table 10: Teaching and learning metacognitive skills: Activities

Activity Identifying cognitive errors Description When students monitor their learning, they can become aware of potential problems, including errors in encoding, operations, and goals. Errors in encoding include missing important data or not separating relevant from irrelevant data. Errors in operations include failing to select the right sub-skills to apply or failing to divide a task into subparts. For example, some math students will jump right to what they think is the final calculation to get the desired answer. Errors in goal seeking include misrepresenting the task and not understanding the criteria to apply. Problems with cognitive load include being unable to handle the number of sub-skills necessary to do a task, or not having enough automatic, internalized subskills. A good way to discover what kind of errors managers are making in their thinking processes is to have them unpack their thinking by explaining, step by step, how they are approaching a given task. This not only allows the instructor to diagnose possible errors, it provides managers with an opportunity to describe their thinking processes, which, by itself, develops their metacognitive abilities. Strategic learning Working in groups, have students generate questions about the content being learned and attempt to answer them. Have students produce written or verbal summaries of course texts. Require students to create examples, make analogies, and explain relationships between concepts. Then, engage students in the use of organizing strategies like concept maps, network representations, and other graphic organizers. Self-regulatory metacognitive questions These questions are designed to follow instruction on a particular topic and precede instruction on the next topic: (a) "What did I learn about this topic?" (monitoring) (b) "With what did I have difficulty?" (monitoring) (c) "What types of things can I do to deal with this difficulty?" (problem solving-planning) (d) "What specific action(s) am I going to take this week to solve any difficulties?" (planning) Before assigning this task for the first time, instructors should work through an example with the group. (McInerney, McInerney, & Marsh, 1997) (Simpson & Nist, 2000) Resource (Nickerson, Perkins, & Smith, 1985)

Metacognition

14

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Activity Cromley summarizes the research findings, then translates them into practical activities for the classroom. This is an excellent resource for adult educators.

Description Skills need to be taught in the context in which they will be used. For example, if students are learning to lead in a high security situation, they need to practice confronting the kinds of issues that come up in high security situations, not just "general" skills. Reading skills are subject-specificunderstanding what you read in a technical report does not guarantee that you will read well in another subject area. Problem-solving skills in one subject area are different from those in other areas. Problem-solving skills need to be taught separately for each subject. Since problem-solving skills do not automatically transfer from one subject area to another, instructors need to show students how to transfer these skills and give them lots of practice. Students need more and better mental models of the world in order to learn and master new information and skills. Thinking skills, such as inferring unstated facts, need to be taught explicitly in the classroom; they do not develop on their own (except in a very few students). These strategies need to be practiced over and over again. Most adult learners have a very limited number of strategies for understanding new material or solving problems. Teaching them more strategies can help them learn much better. Learning lasts when the student understands the material, not just memorizes it. Information needs to be presented in small chunks so that working memory can process it. Students need immediate practice to move information from working memory to long-term memory. It is impossible to remember without associating new information with what you already know.

Resource (Cromley, 2000)

Authors provide an overview of scaffolding and its effects on learning.

(From the abstract) This paper proposes an expanded conception of scaffolding with four key elements: (i) scaffolding agency expert, reciprocal, and self-scaffolding; (ii) scaffolding domain conceptual and heuristic scaffolding; (iii) the identification of self-scaffolding with metacognition; and (iv) the identification of six zones of scaffolding activity; each zone distinguished by the matter under construction and the relative positioning of the participant(s) in the act of scaffolding.

(Holton & Clarke, 2006)

Metacognition

15

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Figure 4: Model of formative assessment and self-regulated learning

Metacognition

16

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Table 12: Metacognition fads Fad Learning styles Claim Different people have different learning styles (that can be measured with survey-type instruments) and these have an impact on learning. Comments Adjusting teaching style to accommodate different learning styles has not been shown to impact learning. Moreover, catering to learning preferences may limit versatility, having a negative effect on learning over time. Much of the data necessary for demonstrating the unique association between EI and work-related behavior appears to reside in proprietary databases, preventing rigorous tests of the measurement devices or of their unique predictive value. For those reasons, any claims for the value of EI in the work setting cannot be made under the scientific mantle (p. 411) Source (Cromley, 2000; Curry, 1990; Stahl, 2002)

Emotional Bringing intelligence to intelligence bear upon emotion.

{Landy, 2005 #14980}

Resources

Table 11: Metacognition curricula

Resource IDEAL problem solving: Identify, Define, Explore, Act, and Look, and Learn. Description The IDEAL problem solving system is based on evidence that successful problem-solvers actively attempt to (a) identify problems that others may have overlooked; (b) develop at least two sets of contrasting goals for any problem and define them explicitly; (c) explore strategies and continually evaluate their relevance to their goals; (d) anticipate the effects of strategies before acting on them; and (e) look at the effects of their efforts and learn from them. (p. 3) Focuses, in part on helping adults manage their own learning using metacognitive skills. Level Premanagement Resources (Bransford, Haynes, Stein, Lin, & NashvilleRead, 1998)

TV411a national television series aimed at adult learners Curricula to enhance students higher order cognitive skills Cognitive Strategy Instruction (CSI)

Premanagement

(D'Amico & Capehart, 2001)

A handbook offering a number of activities designed for adult learners. Many of these are appropriate for premanagers, especially if they are contextualized (free from Eric). An instructional approach that has been shown to enhance learning by emphasizing the development of thinking skills and processes. The objective is to enable all students to become more strategic, self-reliant, flexible, and productive learners. A useful resource for students of critical thinking in the workplace.

Premanagement

(Carman & Askov, 1994)

Premanagement

(Scheid, 1993)

Using critical thinking to gain knowledge and understanding

Premanagement

http://www.unisa net.unisa.edu.au /Resources/nursi ng/Critical%20thi nking/Critical%2 0thinking.htm

Metacognition

17

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Resource Designing metacognitive activities

Description Several research-based suggestions for creating learning activities with a strong metacognitive component

Level

Resources (Lin, 2001)

Table 12: Metacognition measures

Resource Lectical Reflective Judgment Assessment (LRJA01) Description An online assessment of reflective judgment skill (for managers). Provides reliable developmental scores in level increments, as well as personalized feedback, including developmentally informed learning suggestions. Intended for personal use, coaching, and course evaluations. The RCI is an online assessment of the capacity to recognize and endorse statements that reflect the attributes of reflective thinking. It is not an assessment of reflective judgment skill, and it is not intended as an assessment of individuals, but can be used to assess group trends. An assessment of students knowledge about critical thinking conceptsthe extent to which they have learned these concepts as they are presented in Elder and Pauls model. It is not an assessment of critical thinking ability. Reliability information is not provided. A pen and paper assessment of critical thinking skill that can be adapted to any subject area. Scoring is done by instructors, and is based on rubrics. Based on the idea of self-regulated learning (SRL), this selfreport instrument is designed to assess motivation and use of learning strategies by college students. The motivation scales tap into three broad areas: (1) value (intrinsic and extrinsic goal orientation, task value), (2) expectancy (control beliefs about learning, self-efficacy); and (3) affect (test anxiety). The learning strategies section is comprised of nine scales which can be distinguished as cognitive, metacognitive, and resource management strategies. The cognitive strategies scales include (a) rehearsal, (b) elaboration, (c) organization, and (d) critical thinking. Metacognitive strategies are assessed by one large scale that includes planning, monitoring, and regulating strategies. Resource management strategies include (a) managing time and study environment; (b) effort management, (c) peer learning, and (d) help-seeking. (abstract) Resources http://devtestservice.com

Reasoning About Current Issues Test (RCI)

http://www.umich.edu/~re fjudg/reasoningaboutcurre ntissuestest.html http://www.criticalthinking. org/courses/critical_think g_test1.cfm

International Critical Thinking Basic Concepts and Understanding Online Test International Critical Thinking Test Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)

http://www.criticalthinking. org/assessment//ICATinfo.cfm (Pintrich, Smith, Garcia, & Mckeachie, 1993)

Metacognition

18

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Resource Structure of Observed Learning Outcomes (SOLO)

Description Method for evaluating learning/reasoning outcomes that involves 5 levels of learning. Is often used to scaffold the development of scoring rubrics. Rubrics are high inference and inter-rater agreement is difficult to maintain. Nonetheless, when inter-rater agreement is properly controlled, the rubrics are reliable enough for course evaluations (not usually for individual evaluation). 1. Pre-structural Learners acquire bits of unconnected information, which have no organization and make no sense. 2. Uni-structural Learners make simple and obvious connections, but show little evidence that their significance has been grasped. 3. Multi-structural Learners make a number of connections, but metaconnections between them are missed, as is their significance for the whole. 4. Relational Learners appreciate the significance of the parts in relation to the whole. 5. Extended abstract Learners make connections both within and beyond the subject area, showing they are able to generalize and transfer the principles and ideas.

Resources (Biggs & Collis, 1982)

Metacognition

19

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

References

Ames, C., & AfIher, J. ( 1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students' learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology., 80, 260-267. Argyris, C. (1991). Teaching smart people how to learn. Harvard Business Review, May-June. Baer, M., Hollenstein, A., Hofstetter, M., Fuchs, M., & Reber-Wyss, M. (1994). How d expert and novice writers differ in their knowledge of the writing process and its regulation (metacognition) from each other, and what are the differences in metacognitive knowledge between writers of different ages? Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Biggs, J., & Collis, K. (1982). Evaluating the quality of learning: The SOLO taxonomy (structure of the observed learning outcome). New York: Academic Press. Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shauna, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7(3), 230-241. Borkowski, J., Carr, M., & Pressely, M. (1987). "Spontaneous" strategy use: Perspectives from metacognitive theory. Intelligence, 11, 61-75. Borkowski, J. G., & Thorpe, P. K. (1994). Self-regulation and motivation: A life-span perspective on underachievement at any point during the life span (B. P. D & A. E. L, Trans.). In B. J. Z. Dale H. Schunk (Ed.), Self-regulation of learning and performance: Issues and educational applications. (pp. 45-73). U Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Hillsdale, NJ, US. Bransford, J. D., Haynes, A. F., Stein, B. S., Lin, X., & NashvilleRead, N. (1998). The IDEAL workplace: Strategies for improving learning, problem solving, and creativity. Bransford, J. D., Sherwood, R., Vye, N. J., & Rieser, J. (1986). Teaching thinking and problem solving. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1078-1089. Brten, I., & Stromso, H. (2005). The relationship between epistemological beliefs, implicit theories of intelligence, and self-regulated learning among Norwegian postsecondary students. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75, 539565. Brown, A. L., Bransford, J. D., Ferrara, R. A., & Campione, J. C. (1983). Learning, remembering, and understanding. In J. H. Flavell & E. M. Markman (Eds.), Carmichael's manual of child psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 77-166 ). New York: Wiley. Bruer, J. (1993). Schools for Thought: A science of learning in the classroom. Cambridge: MIT Press. Byars-Winston, A. M., & Fouad, N. A. (2006). Metacognition and multicultural competence: Expanding the culturally appropriate career counseling model. Career Development Quarterly, 54, 187-201. Carman, P. S., & Askov, E. N. (1994). Development of a curriculum to enhance adult learners higher order skills. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State Universityo. Document Number) Carr, M., Kurtz, B. E., Schneider, W., Turner, L. A., & Borkowski, J. G. (1989). Strategy acquisition and transfer among German and American children: Environmental influences on metacognitive development. Developmental Psychology, 25, 765-771. Como, L. (1986). The metacognitive control components of self-regulated learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 11, 333-346. Cromley, J. (2000). Learning to think: Learning to learn. Washington, DC: National Institute for Literacyo. Document Number) Curry, L. (1990). One critique of the research on learning styles. Educational Leadership, 48, 50-56. D'Amico, D., & Capehart, M. A. (2001). Letting Learners Lead: Theories of Adult Learning and TV411. Focus on Basics, 5(B), 35-41. Daley, B. J. (2002). Facilitating learning with adult students through concept mapping. Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 50(1), 21-32. Dresel, M., & Haugwitz, M. (2005). The relationship between cognitive abilities and self-regulated learning: Evidence for interactions with academic self-concept and gender. High ability studies, 16(2), 201-218. Duchon, D., Ashmos, D., & Dunegan, K. J. (1991). Avoid decision making disaster by considering psychological bias. Review of Business, 13. Enos, M. D., Kehrhahn, M. T., & Bell, A. (2003). Informal learning and the transfer of learning: How managers develop proficiency. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 14(4), 369-. Ericsson, K., Chase, W., & Faloon, S. (1980). Acquisition of a memory skill. Science and Engineering Ethics, 208, 1181-1182. Ewell- Kumar, A. (1999). The influence of metacognition on managerial hiring decision making: Implications for management development Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 59(10-A). Fischer, K. W., & Pruyne, E. Reflective thinking in adulthood: Development, variation, and consolidation. In J. Demick (Ed.), Handbook of Adult Development.

Metacognition

20

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Fischer, K. W., Yan, Z., & Stewart, J. B. Adult cognitive development: Dynamics in the developmental web. In J. Valsiner & K. Connoly (Eds.), Handbook of developmental psychology (pp. 491-516). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911. Flavell, J. H. (1981). Cognitive monitoring. In W. P. Dickson (Ed.), Children's oral communication skills (pp. 35-60). New York: Academic. Garland, E. L. (2007). The meaning of mindfulness: A second-order cybernetics of stress, metacognition, and coping. Complementary Health Practice Review, 12(1), 15-30. Garner, R. (1990). When children and adults do not use learning strategies: Toward a theory of settings. Review of Educational Research, 60, 517-529. Garner, R., & Alexander, P. A. (1989). Metacognition: Answered and unanswered questions. Educational Psychologist, 24(2), 143-158. Ghatala, E. S. (1986). Strategy-monitoring training enables young learners to select effective strategies. Educational Psychologist, 21, 43-54. Glaser, R. (1984). Education and thinking: The role of knowledge. American Psychologist, 39, 93-104. Glenberg, A. M., Wilkinson, A. C., & Epstein, W. (1982). The illusion of knowing: Failure in the self-assessment of comprehension. Memory & Cognition, 10, 597-602. Hascher, T. A., & Oser, F. (1995). Promoting autonomy in the workplace--A cognitive-developmental intervention. Paper presented at the Annual Meeing of the American Educational Research Association. Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Hofer, B. K. (2004). Epistemological understanding as a metacognitive process: Thinking aloud during online searching. Educational Psychologist, 39(1), 43-55. Hofer, B. K., & Yu, S. L. (2003). Teaching self-reglated learning through a "learning to learn" course. Teaching in Psychology, 30(1), 30-33. Holton, D., & Clarke, D. (2006). Scaffolding and metacognition. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology,, 37(2), 127-143. Kitchener, K. S., & Fischer, K. W. (1990). A skill approach to the development of reflective thinking. Contributions to Human Development, 21, 48-62. Kitchener, K. S., & King, P. M. (1990). The reflective judgment model: ten years of research. In M. L. Commons, C. Armon, L. Kohlberg, F. A. Richards, T. A. Grotzer & J. D. Sinnott (Eds.), Adult development (Vol. 2, pp. 62-78). New York: Praeger. Kuhn, D., Shaw, V., & Felton, M. (1997). Effects of dyadic interaction on argumentative reasoning. Cognition and Instruction, 15(3), 287-315. Lin, X. (2001). Designing metagognitive activities. Educational Technology, Research, & Development, 49, 23-40. Mace, F. C., Belfiore, P. J., & Hutchinson, J. M. (2001). Operant theory and research on self regulation. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Self-regulated learning and academic achievement (pp. 39-65). Mahwah, NJ: Eribaum. Mathan, S., & Koedinger, K. R. (2005). Fostering the intelligent novice: Learning from errors with metacognitive tutoring. Educational Psychologist, 40(4), 257-265. McCombs, B. L., & Marzano, R. J. (1990). Putting the self into self-regulating learning: The self as agent in integrating will and skill. Educational Psychologist, 25(51-69). McInerney, V., McInerney, D. M., & Marsh, H. W. (1997). Effects of metacognitive strategy training within a cooperative group learning context on computer achievement and anxiety: An aptitude treatment interaction study. Journal of Educational Psychology., 89(4), 686-695. Mills, C. M., & Keil, F. C. (2004). Knowing the limits of one's understanding: The development of an awareness of an illusion of explanatory depth. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 87, 1-32. Muis, K. R. (2007). The role of epistemic beliefs in self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 42(3), 173-190. Nickerson, R. S., Perkins, D. N., & Smith, E. E. (1985). The teaching of thinking. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Nicol, D. J., & MacFarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218. Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2006). Critical thinking: The nature of critical and creative thought. Journal of Developmental Education, 30(2), 34-35. Perkins, D. (1987). Knowledge as design: Teaching thinking through content. In J. B. R. Sternberg (Ed.), Teaching thining skills: Theory and practice. New York: W. H. Freeman. Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & Mckeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53, 801813. Pressley, M., & Ghatala, E. S. (1990). Self-regulated learning: Monitoring learning from text. Educational Psychologist, 25, 9-33. Schloemer, P., & Brenan, K. (2006). Journal of Education for Business, 81-87.

Metacognition

21

Developmental Testing Service, LLC

Schunk, D. H. (1990). Goal setting and self-efficacy during self-regulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 25, 7186. Simpson, M. L., & Nist, S. L. (2000). An update on strategic learning: Its more than textbook reading strategies. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 43, 528-541. Sperling, R. A., Howard, B. C., Staley, R., & DuBois, N. (2004). Metaognition and self-regulated learning constructs. Educational Research and Evaluation, 10(2), 117-139. Stahl, S. A. (2002). Different strokes for different folks? In L. Abbedutto (Ed.), Taking sides: Clashing on controversial issuesin educational psychology (pp. 98-107). Guilford, CT: McGraw-Hill. Sungur, S., & Tekkaya, C. (2006). Effects of problem-based learning and traditional instruction on self-regulated learning. Journal of Educational Research, 99(5), 307-317. Swanson, L., & Hill, G. (1993). Metacognitive aspects of moral reasoning and behavior. Adolescence, 28, 711-735. Thomas, D. C. (2006). Domain and development of cultural intelligence: The importance of mindfulness. Group & Organization Management, 31(1), 78-99. Vukman, K. B. (2005). Developmental differences in metacognition and their connections with cognitive development in adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 12(4), 211-221. Wells, A. (2005). Detached mindfulness In cognitive therapy: A metacognitive analysis and ten techniques. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 23(4), 337-355. Wood, P., & Kardash, C. A. (2002). Critical elements in the design and analysis of studies of epistemology. In B. K. Hofer & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Personal epistemology: The psychology of beliefs about knowledge and knowing (pp. 231260). Maswah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Wood, P. K. (1997). A secondary analysis of claims regarding the Reflective Judgment interview: Internal consistency, sequentiality and intra-individual differences in ill-structured problem-solving. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 12, pp. 243-312). New York: Agathon. Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 3-17. Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2001). Reflections on theories of self-regulated learning and academic achievement. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives (pp. (pp. 289-307). Eribaum: Mahwah, NJ.

Metacognition

22

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Frederick Taylor and The Scientific ManagementDocument85 pagesFrederick Taylor and The Scientific ManagementJohn ReyPas encore d'évaluation

- Measuring Learning Strategies Using QuestionnairesDocument19 pagesMeasuring Learning Strategies Using QuestionnairesguankunPas encore d'évaluation

- MILLER'S Information Processing TheoryDocument34 pagesMILLER'S Information Processing TheoryDarlen May Dalida100% (1)

- KV Petrides, A Drian Furnham Và Norah - Tri Tue Cam XucDocument4 pagesKV Petrides, A Drian Furnham Và Norah - Tri Tue Cam XucNguyễn Huỳnh Trúc100% (1)

- Learning Theories ProfileDocument2 pagesLearning Theories ProfiletracycwPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Strategies InventoryDocument18 pagesLearning Strategies InventoryArlene AmorimPas encore d'évaluation

- Self Directed LearningDocument10 pagesSelf Directed LearningCa MinantePas encore d'évaluation

- Locus of Control de Julian RotterDocument30 pagesLocus of Control de Julian RotterMaríaVásquezRojasPas encore d'évaluation

- Theories of AttitudeDocument4 pagesTheories of Attitudeimcoolneha_soniPas encore d'évaluation

- Tet GordonDocument39 pagesTet Gordonapi-350463121Pas encore d'évaluation

- Exploring Theories Applicable to Educational and Social Sciences ResearchDocument4 pagesExploring Theories Applicable to Educational and Social Sciences ResearchLoraine Magistrado AbonitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kolb's Theory of Experiential LearningDocument13 pagesKolb's Theory of Experiential LearningPiyush AggarwalPas encore d'évaluation

- Flow The Psychology of Optimal ExperienceDocument6 pagesFlow The Psychology of Optimal ExperienceJdalliXPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing Creativity at WorkDocument4 pagesDeveloping Creativity at WorkCharis ClarindaPas encore d'évaluation

- Article UCSF SEJC January 2017Document6 pagesArticle UCSF SEJC January 2017AnyrchivePas encore d'évaluation

- Kolb Theory of Learning StylesDocument4 pagesKolb Theory of Learning Stylessolo_gauravPas encore d'évaluation

- Lerning Object Systems and Strategies-López-lectura2-15-02-2017-M1-01Document10 pagesLerning Object Systems and Strategies-López-lectura2-15-02-2017-M1-01Juan Gabriel Lopez HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory ExplainedDocument27 pagesBronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory ExplainedVenice Kaye NalupaPas encore d'évaluation

- Neuroleadership: A Conceptual Analysis and Educational ImplicationsDocument21 pagesNeuroleadership: A Conceptual Analysis and Educational Implicationspooja subramanyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bolo de BeterrabaDocument11 pagesBolo de BeterrabaMarta CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Culture, Cognition and Intelligence: Dimitrios ThanasoulasDocument8 pagesCulture, Cognition and Intelligence: Dimitrios ThanasoulaskalaentaxeiPas encore d'évaluation

- Morality and Positive PsychologyDocument4 pagesMorality and Positive Psychologyalchemics38130% (1)

- BehaviorismDocument5 pagesBehaviorismytsotetsi67Pas encore d'évaluation

- Students Learning Styles and Self MotivationDocument15 pagesStudents Learning Styles and Self MotivationJennybabe PizonPas encore d'évaluation

- Measuring Attitudes with ScalesDocument8 pagesMeasuring Attitudes with ScalesSharat ChandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Baumrind's 3 Parenting StylesDocument1 pageBaumrind's 3 Parenting StylesMoldovan Diana100% (1)

- Accelerated Learning Techniques For Adults - An Instructional Design PDFDocument29 pagesAccelerated Learning Techniques For Adults - An Instructional Design PDFAnthony Charles APas encore d'évaluation

- Locus of control and its relationship to organisational behaviourDocument22 pagesLocus of control and its relationship to organisational behaviouralice3alexandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Promoting Cooperative Learning and Social Skills with Children's LiteratureDocument12 pagesPromoting Cooperative Learning and Social Skills with Children's Literaturedavidput1806Pas encore d'évaluation

- ADULT LEARNING STYLES AND PEDAGOGY VS ANDRAGOGYDocument8 pagesADULT LEARNING STYLES AND PEDAGOGY VS ANDRAGOGYperestainPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Work Environment on Employee PerformanceDocument16 pagesImpact of Work Environment on Employee PerformanceKhizra SaleemPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Styles of Physiotherapists: A Systematic Scoping ReviewDocument9 pagesLearning Styles of Physiotherapists: A Systematic Scoping ReviewAndy Delos ReyesPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership Between Org Learning KMDocument15 pagesPartnership Between Org Learning KManashussainPas encore d'évaluation

- Group Supervision-Focus On CountertransferenceDocument13 pagesGroup Supervision-Focus On CountertransferenceLudmillaTassanoPitrowsky100% (1)

- Educating the Emotional Mind for 21st Century SuccessDocument6 pagesEducating the Emotional Mind for 21st Century SuccesstitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Emotional Aspects of LearningDocument16 pagesEmotional Aspects of Learninghaddi awanPas encore d'évaluation

- Krapfl, Gasparotto - 1982 - Behavioral Systems AnalysisDocument18 pagesKrapfl, Gasparotto - 1982 - Behavioral Systems AnalysisCamila Oliveira Souza PROFESSORPas encore d'évaluation

- Strengths and Limitations of Sociocultural TheoryDocument2 pagesStrengths and Limitations of Sociocultural TheoryAdler Psalm0% (1)

- Lave and Wenger Chapter 1Document3 pagesLave and Wenger Chapter 1danielnovakPas encore d'évaluation

- The Role of Self-Regulated LearningDocument17 pagesThe Role of Self-Regulated LearningMikail KayaPas encore d'évaluation

- TriarchicDocument3 pagesTriarchicglphthangPas encore d'évaluation

- MSCEITDocument1 pageMSCEITKhyaatiPas encore d'évaluation

- EmpatiaDocument21 pagesEmpatiarominaDnPas encore d'évaluation

- Problem Solving ApproachDocument1 pageProblem Solving ApproachPatricio J. VásconesPas encore d'évaluation

- EmotionalIntelligenceAcceptedVersion BhullarSchutte2018Document11 pagesEmotionalIntelligenceAcceptedVersion BhullarSchutte2018trainer yoga100% (1)

- Peking University Review Analyzes Teachers' Practical KnowledgeDocument23 pagesPeking University Review Analyzes Teachers' Practical KnowledgemarilouatPas encore d'évaluation

- Theory of Reasoned ActionDocument8 pagesTheory of Reasoned ActionraulrajsharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Practical IntelligenceDocument6 pagesPractical Intelligenceshishiir saawantPas encore d'évaluation

- Self Determination TheoryDocument16 pagesSelf Determination TheoryNurbek KadyrovPas encore d'évaluation

- Being An Expert Professional PractitionerDocument183 pagesBeing An Expert Professional PractitionerRio Michelle Corrales100% (2)

- Tranquil Waves of Teaching, Learning and ManagementDocument11 pagesTranquil Waves of Teaching, Learning and ManagementGlobal Research and Development ServicesPas encore d'évaluation

- Self-Regulated Learning - Where We Are TodayDocument13 pagesSelf-Regulated Learning - Where We Are Todayvzzvnumb100% (1)

- Adult Learning StylesDocument13 pagesAdult Learning StylesEsha VermaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Emotional Intelligence - WikipediaDocument10 pagesEmotional Intelligence - WikipediaJellie MendozaPas encore d'évaluation

- Understanding Child Development and Motivation TheoriesDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Child Development and Motivation TheoriesShanePas encore d'évaluation

- Albert Bandura Social LearingDocument35 pagesAlbert Bandura Social LearingAfsana khanPas encore d'évaluation

- MAKING WELLBEING PRACTICAL: AN EFFECTIVE GUIDE TO HELPING SCHOOLS THRIVED'EverandMAKING WELLBEING PRACTICAL: AN EFFECTIVE GUIDE TO HELPING SCHOOLS THRIVEPas encore d'évaluation

- Context Based Learning A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionD'EverandContext Based Learning A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionPas encore d'évaluation

- UCC DBMS Exam April 2012Document13 pagesUCC DBMS Exam April 2012Duval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundation Math - Graded Assignment 1Document1 pageFoundation Math - Graded Assignment 1Duval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Python CheatsheetDocument9 pagesPython CheatsheetDuval Pearson0% (1)

- Object Oriented Programming C++-2008Document6 pagesObject Oriented Programming C++-2008Duval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundation Mathematics-DeCEMBER 15, 2011Document5 pagesFoundation Mathematics-DeCEMBER 15, 2011Duval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Multimodal Learning Through MediaDocument24 pagesMultimodal Learning Through MediaDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundation Mathematics-MAY 02, 2011Document4 pagesFoundation Mathematics-MAY 02, 2011Duval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Steel Konig Integrating Theories of MotivationDocument26 pagesSteel Konig Integrating Theories of MotivationDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 5-Consumer Arithmetic - UnlockedDocument12 pagesLesson 5-Consumer Arithmetic - UnlockedDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning and Teaching Strategies American Scientist ArticleDocument4 pagesLearning and Teaching Strategies American Scientist ArticleDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundation Mathematics-AUGUST 26, 2011Document4 pagesFoundation Mathematics-AUGUST 26, 2011Duval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Scientific American July 21 2009 Guest Blog ArticleDocument9 pagesScientific American July 21 2009 Guest Blog ArticleDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Theorists of PsychologyDocument3 pagesTheorists of PsychologyDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- LearningDocument29 pagesLearningDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Ericsson - Deliberate PracticeDocument44 pagesEricsson - Deliberate PracticeKenny CuiPas encore d'évaluation

- A Practical Guide To Critical Thinking-HaskinsDocument20 pagesA Practical Guide To Critical Thinking-HaskinsDuval Pearson0% (1)

- Motivation - An Article On ProcrastinationDocument21 pagesMotivation - An Article On ProcrastinationDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Art CL NSF Visual Lang VDocument11 pagesArt CL NSF Visual Lang VDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Creative Stress Management TechniquesDocument8 pagesCreative Stress Management TechniquesDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Becoming A Better LearnerDocument24 pagesBecoming A Better LearnerDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Programming Techniques 2011 EOMDocument5 pagesProgramming Techniques 2011 EOMDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Programming Techniques 2010 EOMDocument7 pagesProgramming Techniques 2010 EOMDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Puntuation Marks and Their UsageDocument2 pagesPuntuation Marks and Their UsageDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundation English 2010Document13 pagesFoundation English 2010Duval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Foundation English 2011Document12 pagesFoundation English 2011Duval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 1-Pronoun Antecedent AgreementDocument2 pagesLecture 1-Pronoun Antecedent AgreementDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Commonly Confused WordsDocument5 pagesCommonly Confused WordsDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture Notes For Sunday June 03, 2012 Content: Problem PartsDocument6 pagesLecture Notes For Sunday June 03, 2012 Content: Problem PartsDuval PearsonPas encore d'évaluation

- 100 Confused WordsDocument7 pages100 Confused WordsDuval Pearson100% (1)

- IUSServer 8 5 SP3 Admin enDocument118 pagesIUSServer 8 5 SP3 Admin enmahmoud rashedPas encore d'évaluation

- Example of A Chronological CVDocument2 pagesExample of A Chronological CVThe University of Sussex Careers and Employability CentrePas encore d'évaluation

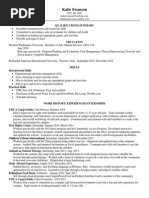

- Katie SwansonDocument1 pageKatie Swansonapi-254829665Pas encore d'évaluation

- Answer: D. This Is A Function of Banks or Banking InstitutionsDocument6 pagesAnswer: D. This Is A Function of Banks or Banking InstitutionsKurt Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- DTC CodesDocument147 pagesDTC CodesV7CT7RPas encore d'évaluation

- Reciprocating - Pump - Lab Manual Ms WordDocument10 pagesReciprocating - Pump - Lab Manual Ms WordSandeep SainiPas encore d'évaluation

- Earthquake Engineering Predicts Structural Response From Ground MotionDocument21 pagesEarthquake Engineering Predicts Structural Response From Ground MotionSamsul 10101997Pas encore d'évaluation

- Edtpa Literacy Context For Learning - Olgethorpe KindergartenDocument3 pagesEdtpa Literacy Context For Learning - Olgethorpe Kindergartenapi-310612027Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jamel P. Mateo, Mos, LPTDocument7 pagesJamel P. Mateo, Mos, LPTmarieieiemPas encore d'évaluation

- 12 Tests of LOVE by Chip IngramDocument3 pages12 Tests of LOVE by Chip IngramJeyakumar Isaiah100% (1)

- SetuplogDocument307 pagesSetuplogJuan Daniel Sustach AcostaPas encore d'évaluation

- El Nido Resorts Official WebsiteDocument5 pagesEl Nido Resorts Official WebsiteCarla Naural-citebPas encore d'évaluation

- Articol Indicatori de PerformantaDocument12 pagesArticol Indicatori de PerformantaAdrianaMihaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Optidrive P2 Elevator User Guide V1 03Document60 pagesOptidrive P2 Elevator User Guide V1 03Mohd Abu AjajPas encore d'évaluation

- Oath of Authenticity Research DocumentsDocument1 pageOath of Authenticity Research DocumentsPrincess Lynn PaduaPas encore d'évaluation

- Students Perceptions of Their Engagement Using GIS Story MapsDocument16 pagesStudents Perceptions of Their Engagement Using GIS Story Mapsjj romeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Pratham Sutone: Academic Record Skill HighlightsDocument1 pagePratham Sutone: Academic Record Skill HighlightsMugdha KolhePas encore d'évaluation

- How to Write Formal IELTS LettersDocument5 pagesHow to Write Formal IELTS Lettersarif salmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Integration Test PlanDocument16 pagesSample Integration Test PlanAnkita WalkePas encore d'évaluation

- Sargent 2014 Price BookDocument452 pagesSargent 2014 Price BookSecurity Lock DistributorsPas encore d'évaluation

- Injectable Polyplex Hydrogel For Localized and Long-Term Delivery of SirnaDocument10 pagesInjectable Polyplex Hydrogel For Localized and Long-Term Delivery of SirnaYasir KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Project ReportDocument61 pagesProject Reportlove goyal100% (2)

- Slab Sample ScheduleDocument1 pageSlab Sample ScheduleJohn Rhey Almojallas BenedictoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dabhol Power Plant: Case Analysis Report OnDocument11 pagesDabhol Power Plant: Case Analysis Report OnDhruv ThakkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Thesis Document1Document51 pagesThesis Document1ericson acebedoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cabarroguis CLUP SEA ReportDocument91 pagesCabarroguis CLUP SEA ReportAlvin Lee Cucio Asuro100% (3)

- Worksheet A: Teacher's Notes: Level 2 (Upper Intermediate - Advanced)Document9 pagesWorksheet A: Teacher's Notes: Level 2 (Upper Intermediate - Advanced)Elena SinisiPas encore d'évaluation

- Asmo Kilo - PL Area BPP Juni 2023 v1.0 - OKDocument52 pagesAsmo Kilo - PL Area BPP Juni 2023 v1.0 - OKasrulPas encore d'évaluation

- 6420B: Fundamentals of Windows Server® 2008 Microsoft® Hyper-V™ Classroom Setup GuideDocument17 pages6420B: Fundamentals of Windows Server® 2008 Microsoft® Hyper-V™ Classroom Setup GuideVladko NikolovPas encore d'évaluation

- HissDocument17 pagesHissJuan Sánchez López67% (3)