Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Capital Punishment

Transféré par

stikadar91Description originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Capital Punishment

Transféré par

stikadar91Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

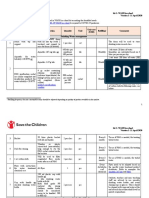

Death Punishment Pro Arguments Con Arguments 1.

Elimination of the murderer by execution is fairAn execution arising out of miscarriage of justice is 1. retribution and saves potential future victims. irreversible. 2. Punishments must match the gravity of offence Reinforce idea of retributive justice a mediaeva 2. and worst crimes should be severely punished. concept in civilized society. 3. Societies must establish deterrents against crime. 3. Capital punishment is lethal vengeance which brutualise the society that tolerates it.

4. Death is a punishment and death penalty has been heldCapital punishment does not have deterrent effect 4. constitutionally valid to ensure justice for condemned Hired murderers take the risk of criminal justice offender. system whatever penalties. 5. Limited to exclusive domain of heinous crime

5. Death penalty is unjust and often discriminatory against poor who cannot defend him. 6. SC has reduced application of death penalty only in 6. Keeping behind the bar for whole life would rather be a rarest of rare case. a deterrent.

7. Death penalty given in a case has to have high courts It leads to failure of justice while comparing with 7. confirmation to determine its accuracy acquittal of guilty persons. 8. Mandatory death sentence has been struck down by 8. In the era of human rights the humanitarian approach SC(sec 303) should be taken. 9. Death sentence subject to clemency 9. Ways of taking life in case of capital punishment very barbaric and in human. Law commission report no. 35th, 42nd and 48 combined. Amnesty International Report 2007(website) Indian penal code 121, 132, 194, 302, 305, 396. Sec 303 mandatory death punishment has been struck down. Constitutionality of death punishment Jagmohan Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh, AIR 1973 SC 947. F a c ts: appellant, who is convicted under s 302, IPC for murder and sentenced to death, The pleaded before the Supreme Court that: (i) Death sentence puts an end to all fundamental rights and therefore is not in the interest of the general public. (ii) The discretion vested in the judges to impose capital punishment is not based on any standards or policy required by the legislature for imposing capital punishment in preference to imprisonment for life. (iii) The uncontrolled and unguided discretion in the judges to impose capital punishment or imprisonment for life is hit by art 14 of the Constitution. 1

(iv) In the absence of any procedure established by law in the matter of sentence, the protection given by art 14 of the Constitution was violated and hence for that reason also, the sentence of death is unconstitutional. Justice Palekar held The first submission is based on the provisions of article 19 of the Constitution. That article does not directly deal with the freedom to live. It deals with seven freedoms [now six] like the freedom of speech and expression, freedom to assemble peaceably and without arms etc, but not directly with the freedom to live. It is, however, contended that freedom to live is basic to all the seven freedoms and since the enjoyment of those seven freedoms is impossible without conceding the freedom to live, the latter cannot be denied by any law unless such law is reasonable and is required in general public interest. It was, therefore, contended that unless it was shown that the sentence of death for murder passed the test of reasonableness and general public interest, it would not be a valid law. The Constitution makers had recognised the death sentence as a permissible punishment and had made constitutional provisions for appeal, reprieve and the like. But more important than these provisions in the Constitution is article 21, which provides that, 'no person shall be deprived of his life except according to procedure established by law.' The implication is very clear. Deprivation of life is constitutionally permissible, if that is done according to the procedure established by law. The issue of abolition or retention has to be decided on a balancing of the various arguments for and against retention. No single argument for abolition or retention can decide the issue. In arriving at any conclusion on the subject, the need for protecting society in general and individual human beings must be borne in mind. It is difficult to rule out the validity of, or the strength behind, many of the arguments for abolition. Nor does the commission treat lightly the argument based on the irrevocability of the sentence of death, the need for a modern approach, the severity of capital punishment and the strong feeling shown by certain sections of public opinion in stressing deeper questions of human values. Having regard, however, to the conditions in India, to the variety of the social upbringing of its inhabitants, to the disparity in the level of morality and education in the country, to the vastness of its area to the diversity of its population and to the paramount need for maintaining law and order in the country at the present juncture, India cannot risk the experiment of abolition of capital punishment. The next contention is that by providing in section 302 of the IPC, that one found guilty there under is liable to be punished either with death sentence or imprisonment for life, the legislature has abdicated its essential function in not providing by legislative standards in what cases the judge should sentence the accused to death and in what cases life imprisonment. In India, the difficulty encountered by the Commission had been overcome long ago and it is accepted by the public that only the judges shall decide the sentence. Where an error is committed in the matter of sentence the same is liable to be corrected by appeals and revisions to higher courts for which appropriate provision was made in the Cr Pc. The structure of our criminal law which is principally contained in the IPC and the Cr PC, underlines the policy that when the legislature

has denned an offence with sufficient clarity and prescribed the maximum punishment, a wide discretion in the matter of fixing the degree of punishment should be allowed to the judge. These considerations naturally include a number of particulars, as of time, place, persons and things, varying according to the nature of the case. Circumstances which are to be considered in alleviation of punishment are as follows: (1) the minority of the offender; (2) the old age of the offender; (3) the condition of the offender's wife, apprentice; (4) the order of a superior military officer; (5) provocation; (6) when offence was committed under a combination of circumstances and influence of motives which are not likely to recur either with respect to the offender or any other; (7) the state of health and the sex of the delinquent. Bentham mentions the following circumstances in mitigation of punishment, which should be inflicted: (1) absence of bad intention; (2) provocation; (3) self-preservation; (4) preservation of some near friends; (5) transgression of the limit of self defence; (6) submission to the menaces; (6) submission to authority; (7) drunkenness; (9) childhood. Appeal dismissed Bachan Singh v State of Punjab AIR 1980 SC 898 Death sentence to be imposed in rarest of rare cases -Supreme Court Facts: The first contention of the appellant is that the provision of death penalty in Sec.302 of the IPC offends art 19 of the Constitution. It is argued that the decision in Maneka Gandhi v Union of India [AIR 1978 SC 579] has given a new interpretative dimension to arts 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution and accordingly, every law of punitive detention both in procedural and substantive aspects must pass the test of all the three articles. By virtue of India acceding in 1979 to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, India is committed to a policy for abolition of the death penalty. Justice Sarkaria (for himself and on behalf of Chandrachud C, AC Gupta and NL Untwalia JJ) stated: (1) The extreme penalty can be inflicted only in the gravest cases of extreme culpability;

(2) In making a choice of the sentence, in addition to the, circumstances of the offence, due regard must be paid to the circumstances of the offender also. For making the choice of punishment or for ascertaining the existence or absence of 'special reasons' in that context, the court must pay due regard both to the crime and the criminal. What is the relative weight to be given to the aggravating and mitigating factors depends on the facts and circumstances of the particular case. A court may, however, in the following cases impose the penalty of death, which may be designated as 'rarest of rare cases' : (a) if the murder has been committed after previous planning and involves extreme brutality; or (b) if the murder involves exceptional depravity; or (c) if the murder is of a member of any of the armed forces of the union or of a member of any police force or of any public servant and was committed: (i) while such member or public servant was on duty; or (ii) in consequence of anything done or attempted to be done by such member or public servant in the lawful discharge of his duty as such member or public servant whether at the time of murder he was such member or public servant, as the case may be, or had ceased to be such member or public servant; or (d) if the murder is of a person who had acted in the lawful discharge of his duty under section 43 of the Cr PC 1973, or who had rendered assistance to a magistrate or a police officer demanding his aid requiring his assistance under section37 and section 129 of the said Code. There can be no objection to the acceptance of these indicators but it would prefer not to fetter judicial discretion by attempting to make an exhaustive enumeration one-way or the other. For all the foregoing reasons, SC rejected the challenge to the constitutionality of the impugned provisions contained in section 302, IPC and 354(3) of the Cr PC 1973. Machhi Singh v State of Punjab, AIR 1983 SC 957 Some standard guidelines given by SC Facts: Machhi Singh and his 11 companions, close relatives and associates were prosecuted under section 302, IPC in five sessions cases. Four of them were awarded death sentence, whereas the sentence of imprisonment for life was imposed on nine of them. The present group of appeals is directed against the aforesaid judgment rendered by the HC. The reasons why the community as a whole does not endorse the humanistic approach reflected in death sentence in no case doctrine are when its collective conscience is so shocked that it will expect the holders of the judicial power centre to inflict death penalty irrespective of their personal opinion as regards desirability or otherwise of retaining death penalty as exemplified in rarest of rare cases evolved in Bachan Singh. The community may entertain such a sentiment when the crime is viewed from the platform of the motive for, or the manner of commission of the crime, or the anti-social or abhorrent nature of the crime, such as for instance:

I. Manner of commission of murder: When the murder is committed in an extremely brutal, grotesque, diabolical, revolting or dastardly manner so as to arouse intense and extreme indignation of the community. For instance: (i) When the house of the victim is set aflame with the end in view to roast him alive in the house; (ii) When the victim is subjected to inhuman acts of torture or cruelty in order to bring about his or her death; and (iii) When the body of the victim is cut into pieces or his body is dismembered in fiendish manner. II. Motive for commission of murder When the murder is committed for a motive, which evinces total depravity and meanness. For instance: (a) When a hired assassin commits murder for the sake of money or reward; (b) When a cold blooded murder is committed with deliberate design in order to inherit property or to gain control over property of a ward or a person under the control of the murdered or when the murdered is in a dominating position or in a position of trust; and (c) When murder is committed in the course of betrayal of the motherland. III. Anti-social or socially abhorrent nature of the crime (a) When murder of a member of a scheduled caste or minority community is committed not for personal reasons but in circumstances which arouse social wrath. For instance, when such a crime is committed in order to terrorise such persons and frighten them into fleeing from a place or in order to deprive them of or make them surrender lands or benefits conferred on them with a view to reverse past injustices and in order to restore the social balance; In cases of bride burning and what are known as dowry-deaths or when murder is committed in order to remarry for the sake of extracting dowry once again or to marry another woman on account of infatuation. IV. Magnitude of crime When the crime is enormous in proportion. For instance, when multiple murders, say, of all or almost all the members of a family or large number of persons of a particular caste, community, or locality are committed . V. Personality of victim of murder When the victim of murder is: An innocent child who could not have or have not provided even an excuse, much less a provocation for murder;

A helpless woman or a person rendered helpless by old age or infirmity; When the victim is a person vis-a.-vis whom the murdered is in a position of domination or trust; and When the victim is a public figure generally loved and respected by the community for the services rendered by him and the murder is committed for political or similar reasons other than personal reasons. In this background the guidelines indicated in the Bachan Singh case will have to be culled out and applied to the facts of each individual e where the question of imposing of death sentence arises. The following propositions emerge from the Bachan Singh case: 1. 2. 3. The extreme penalty of death need not be inflicted except in gravest cases of extreme culpability; Before opting for the death penalty the circumstances of the 'offender' also require to be taken into consideration along with the circumstances of the 'crime'. Life imprisonment is the rule, and death sentence is an exception. In other words death sentence must be imposed only when life imprisonment appears to be an altogether inadequate punishment having regard to the relevant circumstances of the crime, and provided and only provided, the option to impose sentence of imprisonment for life cannot be conscientiously exercised having regard to the nature and circumstances of the crime and all the related circumstances. A balance-sheet of aggravating and mitigating circumstances has to be drawn up and in doing so the mitigating circumstances have to be accorded full weightage and a just balance has to be struck between the aggravating and the mitigating circumstances before the option is exercised.

4.

In order to apply these guidelines inter alia the following questions may be asked and answered: (a) Is there something uncommon about the crime which renders sentence of imprisonment for life inadequate and calls for death sentence? (b) Are the circumstances of the crime such that there is no alternative but to impose death sentence even after according maximum weightage to the mitigating circumstances which speak in favour of the offender? If upon taking an overall global view of all the circumstances in the light of the aforesaid proposition and taking into account the answers to the questions posed hereinabove, the circumstances of the case are such that death sentence is warranted, the court would proceed to do so. The death sentence imposed on the appellants ... having been confirmed, the sentence shall be executed in accordance with law. The appeal is dismissed.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Intention To Create Legal Relations - 001Document5 pagesIntention To Create Legal Relations - 001stikadar91100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- UOI Vs MHD Nazim (Brief)Document1 pageUOI Vs MHD Nazim (Brief)stikadar91Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Abdul Hasis v. Masum AliDocument1 pageAbdul Hasis v. Masum Alistikadar91Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Synopsis Naveen KohliDocument7 pagesSynopsis Naveen Kohlistikadar91100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Contracts JVDocument25 pagesContracts JVstikadar91Pas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Balco Important PartsDocument4 pagesBalco Important Partsstikadar91Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Article 12 Cases SummariesDocument4 pagesArticle 12 Cases Summariesstikadar9163% (8)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- MarxismDocument5 pagesMarxismstikadar91Pas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- BS en Iso 11666-2010Document26 pagesBS en Iso 11666-2010Ali Frat SeyranPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Gogte Institute of Technology: Karnatak Law Society'SDocument33 pagesGogte Institute of Technology: Karnatak Law Society'SjagaenatorPas encore d'évaluation

- MSDS Bisoprolol Fumarate Tablets (Greenstone LLC) (EN)Document10 pagesMSDS Bisoprolol Fumarate Tablets (Greenstone LLC) (EN)ANNaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- DFUN Battery Monitoring Solution Project Reference 2022 V5.0Document50 pagesDFUN Battery Monitoring Solution Project Reference 2022 V5.0A Leon RPas encore d'évaluation

- Invoice Acs # 18 TDH Dan Rof - Maret - 2021Document101 pagesInvoice Acs # 18 TDH Dan Rof - Maret - 2021Rafi RaziqPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Chapter 1.4Document11 pagesChapter 1.4Gie AndalPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Consultancy Services For The Feasibility Study of A Second Runway at SSR International AirportDocument6 pagesConsultancy Services For The Feasibility Study of A Second Runway at SSR International AirportNitish RamdaworPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Qualifi Level 6 Diploma in Occupational Health and Safety Management Specification October 2019Document23 pagesQualifi Level 6 Diploma in Occupational Health and Safety Management Specification October 2019Saqlain Siddiquie100% (1)

- Common OPCRF Contents For 2021 2022 FINALE 2Document21 pagesCommon OPCRF Contents For 2021 2022 FINALE 2JENNIFER FONTANILLA100% (30)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Rundown Rakernas & Seminar PABMI - Final-1Document6 pagesRundown Rakernas & Seminar PABMI - Final-1MarthinPas encore d'évaluation

- How To Unbrick Tp-Link Wifi Router Wr841Nd Using TFTP and WiresharkDocument13 pagesHow To Unbrick Tp-Link Wifi Router Wr841Nd Using TFTP and WiresharkdanielPas encore d'évaluation

- EMI-EMC - SHORT Q and ADocument5 pagesEMI-EMC - SHORT Q and AVENKAT PATILPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- CE5215-Theory and Applications of Cement CompositesDocument10 pagesCE5215-Theory and Applications of Cement CompositesSivaramakrishnaNalluriPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- For Exam ReviewerDocument5 pagesFor Exam ReviewerGelyn Cruz67% (3)

- Strength and Microscale Properties of Bamboo FiberDocument14 pagesStrength and Microscale Properties of Bamboo FiberDm EerzaPas encore d'évaluation

- GSMDocument11 pagesGSMLinduxPas encore d'évaluation

- Https Code - Jquery.com Jquery-3.3.1.js PDFDocument160 pagesHttps Code - Jquery.com Jquery-3.3.1.js PDFMark Gabrielle Recoco CayPas encore d'évaluation

- A Case On Product/brand Failure:: Kellogg's in IndiaDocument6 pagesA Case On Product/brand Failure:: Kellogg's in IndiaVicky AkhilPas encore d'évaluation

- Starrett 3812Document18 pagesStarrett 3812cdokepPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Kit 2: Essential COVID-19 WASH in SchoolDocument8 pagesKit 2: Essential COVID-19 WASH in SchooltamanimoPas encore d'évaluation

- CoP - 6.0 - Emergency Management RequirementsDocument25 pagesCoP - 6.0 - Emergency Management RequirementsAnonymous y1pIqcPas encore d'évaluation

- Bondoc Vs PinedaDocument3 pagesBondoc Vs PinedaMa Gabriellen Quijada-TabuñagPas encore d'évaluation

- DTMF Controlled Robot Without Microcontroller (Aranju Peter)Document10 pagesDTMF Controlled Robot Without Microcontroller (Aranju Peter)adebayo gabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Hyundai Himap BcsDocument22 pagesHyundai Himap BcsLim Fung ChienPas encore d'évaluation

- Stainless Steel 1.4404 316lDocument3 pagesStainless Steel 1.4404 316lDilipSinghPas encore d'évaluation

- On Applied EthicsDocument34 pagesOn Applied Ethicsamanpatel78667% (3)

- A.2 de - La - Victoria - v. - Commission - On - Elections20210424-12-18iwrdDocument6 pagesA.2 de - La - Victoria - v. - Commission - On - Elections20210424-12-18iwrdCharisse SaratePas encore d'évaluation

- China Ve01 With Tda93xx An17821 Stv9302a La78040 Ka5q0765-SmDocument40 pagesChina Ve01 With Tda93xx An17821 Stv9302a La78040 Ka5q0765-SmAmadou Fall100% (1)

- Completed NGC3 ReportDocument4 pagesCompleted NGC3 ReportTiCu Constantin100% (1)

- Company Law Handout 3Document10 pagesCompany Law Handout 3nicoleclleePas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)