Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

How Beethoven Helped Build Japan

Transféré par

AndrewCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

How Beethoven Helped Build Japan

Transféré par

AndrewDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

August 29, 1980

NEW SOLIDARITY Page 3

Music: Vivian Zoakos

How Beethoven Helped Build Japan

This column has asserted that anytime, anywhere in the world where republicans attempted to bring industrialism to a developing country, they regarded the music of Bach and Beethoven as indispensable. We recently discussed music in Mexico; the case of modern Japan, this century's most impressive economic miracle, proves the argument again. The 1868 Meiji Revolution, which transformed Japan from a feudal zerogrowth Confucian society into a modern nation, was accomplished with the aid of Abraham Lincoln Republicans from the U.S.A. The Meiji conspiracy was based on the ideas of Kepler, Spinoza, Alexander Hamilton and his successor, economist Henry Carey. The American allies of Meiji Japan did not neglect the importance of music. In 1875, seven years after the Meiji Revolution an official of the newly set up Education Ministry, Shuji Izawa, was dispatched to the United States to learn how to set up a public school system. Shuji met Luther Whiting Mason, director of the Boston Music School and a teacher at Harvard University. Mason told Shuji that part of the education program must include the music of the German classical masters. Three years later the Meiji government brought Mason to Japan to found and direct the Tokyo Music School. The school's purpose was to educate performers as well as teachers for the public schools, where music education focusing on singing was to be made compulsory. The leaders of the Tokyo Music School pointed out that when they said "music," they meant Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. Since Japan had previously been using the barbaric pentatonic scale, the process of propagating Western music widely took years. At first, performed music consisted primarily of Schubert songs and Beethoven or Haydn piano sonatas, with occasional performances of movements from Bach concerti or Haydn's and Beethoven's early symphonies. Choruses began singing at first in unison and only later in full four-part singing.

Johannes Brahms may have played an important role in aiding Japan's musical development. In 1884 the government sent Shohei Tanaka to Germany to study under the celebrated physicist Hermann Helmholtz. Tanaka was also to study music with two of Brahms's closest collaborators, the violinist Joseph Joachim and the conductor Hans Von Bulow. Meiji-era Japan saw battles back and forth between two business factions, the humanist, Lincoln-allied Mitsubishi faction and the pro-British Mitsui faction. On more than one occasion, when the Mitsui faction came to power, they disbanded the Tokyo Music School, and when the Mitsubishi faction returned to power they reestablished the school. To combat the authority of the humanists, the Mitsui faction and its British mentors insisted there was another Western musical traditionthe music of military bands and Wagner. When the British gained an important role in the guidance of the Japanese Navy, they set up military bands under the direction of J.W. Fenton. Fenton trained the bands in such western music as "Annie Laurie" and "Old Lang Syne." For "serious" music the band performed sections of Wagner operas. The fate of music followed the course of the overall political developments in Japan. Prior to the 1902 Anglo-Japanese military alliance, concerts consisted primarily of Bach, Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert. After 1902, antihumanist musicians such as Wagner, Debussy, Saint-Saens and Liszt came to be performed alongside the humanists. Despite the efforts of the British-Mitsui faction, the Mitsubishi humanists and their American allies succeeded in irrevocably establishing a love for the world's greatest music in Japan. Today, every December as part of the New Year's festivities, there are scores of festivals featuring Beethoven's Ninth Symphony across Japan. This column was contributed by Richard Katz, a specialist in the Meiji period in Japan.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Colds Are Linked To Mental StateDocument3 pagesColds Are Linked To Mental StateAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- The Northern Renaissance, The Nation State, and The Artist As CreatorDocument5 pagesThe Northern Renaissance, The Nation State, and The Artist As CreatorAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- John Burnip On Yordan YovkovDocument6 pagesJohn Burnip On Yordan YovkovAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Presidents Who Died While Fighting The British: Zachary TaylorDocument7 pagesPresidents Who Died While Fighting The British: Zachary TaylorAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- John Quincy Adams and PopulismDocument16 pagesJohn Quincy Adams and PopulismAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- The Capitol Dome - A Renaissance Project For The Nation's CapitalDocument4 pagesThe Capitol Dome - A Renaissance Project For The Nation's CapitalAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Woodrow Wilson and The Democratic Party's Legacy of ShameDocument26 pagesWoodrow Wilson and The Democratic Party's Legacy of ShameAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- How The Malthusians Depopulated IrelandDocument12 pagesHow The Malthusians Depopulated IrelandAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Munich's Lesson For Ronald ReaganDocument22 pagesMunich's Lesson For Ronald ReaganAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Emperor Shi Huang Ti Built For Ten Thousand GenerationsDocument3 pagesEmperor Shi Huang Ti Built For Ten Thousand GenerationsAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Like William Tell, Machiavelli and Cincinnatus: WashingtonDocument6 pagesLike William Tell, Machiavelli and Cincinnatus: WashingtonAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- USA Must Return To American System EconomicsDocument21 pagesUSA Must Return To American System EconomicsAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- How John Quincy Adams Built Our Continental RepublicDocument21 pagesHow John Quincy Adams Built Our Continental RepublicAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Don't Entrust Your Kids To Walt DisneyDocument31 pagesDon't Entrust Your Kids To Walt DisneyAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Mozart As A Great 'American' ComposerDocument5 pagesMozart As A Great 'American' ComposerAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Anniversary of Mozart's Death - The Power of Beauty and TruthDocument18 pagesAnniversary of Mozart's Death - The Power of Beauty and TruthAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Geometrical Properties of Cusa's Infinite CircleDocument12 pagesGeometrical Properties of Cusa's Infinite CircleAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Happy 200th Birthday, Gioachino RossiniDocument2 pagesHappy 200th Birthday, Gioachino RossiniAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- William Lemke and The Bank of North DakotaDocument30 pagesWilliam Lemke and The Bank of North DakotaAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Mexico's Great Era of City-BuildingDocument21 pagesMexico's Great Era of City-BuildingAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- How Lincoln Was NominatedDocument21 pagesHow Lincoln Was NominatedAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- The Shape of Things To ComeDocument20 pagesThe Shape of Things To ComeAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- British Terrorism: The Southern ConfederacyDocument11 pagesBritish Terrorism: The Southern ConfederacyAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- America's Railroads and Dirigist Nation-BuildingDocument21 pagesAmerica's Railroads and Dirigist Nation-BuildingAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- What The Other Gulf War Did To AmericaDocument19 pagesWhat The Other Gulf War Did To AmericaAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Inspirational Role of Congressman John Quincy AdamsDocument5 pagesInspirational Role of Congressman John Quincy AdamsAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- The Federalist Legacy: The Ratification of The ConstitutionDocument16 pagesThe Federalist Legacy: The Ratification of The ConstitutionAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Industrial Corporation Created by The Nation StateDocument12 pagesModern Industrial Corporation Created by The Nation StateAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Project Democracy Hates Juan Domingo PeronDocument11 pagesWhy Project Democracy Hates Juan Domingo PeronAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- Foreign Enemies Who Slandered FranklinDocument9 pagesForeign Enemies Who Slandered FranklinAndrewPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Fourth Grade Vocabulary Success by Sylvan Learning - ExcerptDocument13 pagesFourth Grade Vocabulary Success by Sylvan Learning - ExcerptSylvan Learning94% (17)

- Circles Downbows TcdaDocument7 pagesCircles Downbows TcdamyjustynaPas encore d'évaluation

- Report TextDocument8 pagesReport TextAEW chPas encore d'évaluation

- Extraocular Muscle Anatomy and Physiology NotesDocument13 pagesExtraocular Muscle Anatomy and Physiology NotesRahul Jasu100% (1)

- Sinkholes by Sandra FriendDocument11 pagesSinkholes by Sandra FriendPineapple Press, Inc.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Input of Dharanis, Newar BuddhismDocument8 pagesInput of Dharanis, Newar BuddhismMin Bahadur shakyaPas encore d'évaluation

- SGA Abstractvolym-4 DigitalDocument386 pagesSGA Abstractvolym-4 Digitalmalibrod100% (1)

- Ligature-Typographic LigatureDocument13 pagesLigature-Typographic LigatureOlga KardashPas encore d'évaluation

- Hologram Projector With Pi: InstructablesDocument7 pagesHologram Projector With Pi: InstructablesvespoPas encore d'évaluation

- Dark RomanticismDocument12 pagesDark RomanticismZainab HanPas encore d'évaluation

- Reflective Essay.1Document31 pagesReflective Essay.1Nora Lyn M. TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Summartónar 2019 Music Festival FAROE ISLANDSDocument13 pagesSummartónar 2019 Music Festival FAROE ISLANDSschoenbergPas encore d'évaluation

- Art Appreciation IntroductionDocument3 pagesArt Appreciation IntroductionJasper Hope De Julian100% (1)

- Subiecte Clasa A V A ConcursDocument2 pagesSubiecte Clasa A V A Concursnitu sorinPas encore d'évaluation

- City Builder 02 - Craftsman PlacesDocument18 pagesCity Builder 02 - Craftsman Placesskypalae100% (3)

- Perbandingan Kata Kerja (Verb1, Verb 2. Verb 3Document2 pagesPerbandingan Kata Kerja (Verb1, Verb 2. Verb 3hikmahPas encore d'évaluation

- NX CAD ProjectDocument1 pageNX CAD ProjectKarthik Kumar YSPas encore d'évaluation

- Exclusive TED Course Handout PDFDocument63 pagesExclusive TED Course Handout PDFAlfie NaemPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre K Kindergarten Alphabet Letter TracingDocument28 pagesPre K Kindergarten Alphabet Letter TracingNeha RawatPas encore d'évaluation

- EBCS EN 1992-1-1 - 2013 - EBCS 2 - FinalDocument3 pagesEBCS EN 1992-1-1 - 2013 - EBCS 2 - FinalAwokePas encore d'évaluation

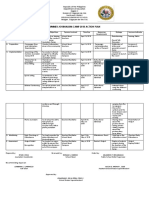

- Action Plan and Journalism Training MatrixDocument5 pagesAction Plan and Journalism Training Matrixryeroe100% (2)

- Alina Bokovikova CVDocument6 pagesAlina Bokovikova CVapi-293798641Pas encore d'évaluation

- PDFDocument11 pagesPDFteodora dragovicPas encore d'évaluation

- Brain Pickings - An Inventory of The Meaningful LifeDocument16 pagesBrain Pickings - An Inventory of The Meaningful Lifegladis rosacia100% (1)

- Soal-Tenses Kls8 2017Document6 pagesSoal-Tenses Kls8 2017Vulkan AbriyantoPas encore d'évaluation

- Present Simple and Past Simple Tenses in EnglishDocument1 pagePresent Simple and Past Simple Tenses in EnglishAnonymous SLYi8ORABPas encore d'évaluation

- The 9 Best Microphones For Voice Over WorkDocument5 pagesThe 9 Best Microphones For Voice Over Workpdf2004Pas encore d'évaluation

- Hadith of The Holy Prophet Muhammad Peace Be Upon HimDocument9 pagesHadith of The Holy Prophet Muhammad Peace Be Upon HimRaees Ali YarPas encore d'évaluation

- Ganpati Mantra For A Desired JobDocument5 pagesGanpati Mantra For A Desired JobBram0% (1)

- AP Literature TermsDocument5 pagesAP Literature TermsGeli LelaPas encore d'évaluation