Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia

Transféré par

ilaria_aDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia

Transféré par

ilaria_aDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil

Yggdrasil

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In Norse mythology, Yggdrasil (pronounced / g.dr .s l/; from Old Norse Yggdrasill, pronounced [ y drasil ]) is an immense tree that is central in Norse cosmology; the world tree, and around the tree exist nine worlds. It is generally considered to mean "Ygg's (Odin's) horse". Yggdrasil is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Yggdrasil is an immense ash tree that is central and considered very holy. The gods go to Yggdrasil daily to hold their courts. The branches of Yggdrasil extend far into the heavens, and the tree is supported by three roots that extend far away into other locations; one to the well Urarbrunnr in the heavens, one to the spring Hvergelmir, and another to the well Mmisbrunnr. Creatures live within Yggdrasil, including the wyrm (dragon) Nhggr, an unnamed eagle, and the stags Dinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Durarr.

"The Ash Yggdrasil" (1886) by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine.

Conflicting scholarly theories have been proposed about the etymology of the name Yggdrasill, the potential that the tree is of another species than ash, the relation to tree lore and to Eurasian shamanic lore, the potential relation to the trees Mmameir and Lrar, Hoddmmis holt, the sacred tree at Uppsala, and the fate of Yggdrasil during the events of Ragnark.

Contents

1 Terminology 2 Attestations 2.1 Poetic Edda 2.1.1 Vlusp 2.1.2 Hvaml 2.1.3 Grmnisml 2.2 Prose Edda 3 Theories 3.1 Shamanic origins 3.2 Mmameir, Hoddmmis holt and Ragnark 3.3 Warden trees, Irminsul, and sacred trees 4 Modern influence 5 See also 6 Notes 7 References

Terminology

1 of 8

25.11.2009 19:30

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil

Yggdrasil comes from Old Norse Yggdrasill.[1] In English, the spellings Yggdrasil, Yggdrasill, and Ygdrasil are used, as shown by entries in English dictionaries and encyclopedias.[2][3][4] It is usually pronounced / g.dr .s l/ in English, and only rarely [ y .dr .sil][5] because the sound [y] does not exist in English and most English speakers are therefore unaccustomed to producing it. The generally accepted meaning of Old Norse Yggdrasill is "Odin's horse", based on the etymology that drasill means "horse" and Ygg(r) is one of Yggdrasil (1895) by Lorenz Odin's many names. The Poetic Edda poem Hvaml describes how Odin Frlich. sacrificed himself to himself by hanging in a tree, making this tree Odin's gallows. This tree was apparently Yggdrasil, and gallows can be called "the horse of the hanged", so Odin's gallows developed into the expression "Odin's horse", which then became the name of the tree.[1] Nevertheless, scholarly opinions regarding the precise meaning of the name Yggdrasill vary, particularly on the issue of whether Yggdrasill is the name of the tree itself or if only the full term askr Yggdrasils refers specifically to the tree, where Old Norse askr means "ash tree". According to this interpretation, askr Yggdrasils means "the world tree upon which 'the horse [Odin's horse] of the highest god [Odin] is bound'". Both of these etymologies rely on a presumed but unattested *Yggsdrasill.[1] A third interpretation, presented by F. Detter, is that the name Yggdrasill refers to the word yggr ("terror"), yet not in reference to the Odinic name, and so Yggdrasill would then mean "tree of terror, gallows". F. R. Schrder has proposed a fourth etymology according to which yggdrasill means "yew pillar", deriving yggia from *igwja (meaning "yew-tree"), and drasill from *dher- (meaning "support").[1]

Attestations

Poetic Edda

In the Poetic Edda, the tree is mentioned in the three poems Vlusp, Hvaml, and Grmnisml. Vlusp In the second stanza of the Poetic Edda poem Vlusp, the vlva (a shamanic seeress) reciting the poem to the god Odin says that she remembers far back to "early times", being raised by jtnar (giants), recalls nine worlds and "nine wood-ogresses" (Old Norse no diiur), and when Yggdrasil was a seed ("glorious tree of good measure, under the ground").[6] In stanza 19, the vlva says:

An ash I know there stands, Yggdrasill is its name, a tall tree, showered with shining loam. From there come the dews that drop in the valleys. It stands forever green over Urr's well.[7]

"Norns" (1832) from Die Helden und Gtter des Nordens, oder das Buch der Sagen.

In stanza 20, the vlva says that from the lake under the tree come three "maidens deep in knowledge" named Urr, Verandi, and Skuld. The maidens "incised the slip of wood," "laid down laws" and "chose

2 of 8

25.11.2009 19:30

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil

lives" for the children of mankind and the destinies (rl g) of men.[8] In stanza 27, the vlva details that she is aware that "Heimdallr's hearing is couched beneath the bright-nurtured holy tree."[9] In stanza 45, Yggdrasil receives a final mention in the poem. The vlva describes, as a part of the onset of Ragnark, that Heimdallr blows Gjallarhorn, that Odin speaks with Mmir's head, and then:

Yggdrasill shivers, the ash, as it stands. The old tree groans, and the giant slips free.[10]

Hvaml In stanza 34 of the poem Hvaml, Odin describes how he once sacrificed himself to himself by hanging on a tree. The stanza reads:

I know that I hung on a windy tree nine long nights, wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin, myself to myself, on that tree of which no man knows from where its roots run.[11]

In the stanza that follows, Odin describes how he had no food nor drink there, that he peered downward, and that "I took up the runes, screaming I took them, then I fell back from there."[11] While Yggdrasil is not mentioned by name in the poem and other trees exist in Norse mythology, the tree is near universally accepted as Yggdrasil, and if the tree is Yggdrasil, then the name Yggdrasil directly relates to this story.[12] Grmnisml In the poem Grmnisml, Odin (disguised as Grmnir) provides the young Odin sacrificing himself upon Agnar with cosmological lore. Yggdrasil is first mentioned in the poem in Yggdrasil (1895) by Lorenz stanza 29, where Odin says that, because the "bridge of the sir burns" and Frlich. the "sacred waters boil," Thor must wade through the rivers Krmt and rmt and two rivers named Kerlaugar to go "sit as judge at the ash of Yggdrasill." In the stanza that follows, a list of names of horses are given that the sir ride to "sit as judges" at Yggdrasil.[13] In stanza 31, Odin says that the ash Yggdrasil has three roots that grow in three directions. He details that beneath the first lives Hel, under the second live frost jtnar, and beneath the third lives mankind. Stanza 32 details that a squirrel named Ratatoskr must run across Yggdrasil and bring "the eagle's word" from above to Nhggr below. Stanza 33 describes that four harts named Dinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Durarr consume "the highest boughs" of Yggdrasil.[13] In stanza 34, Odin says that more serpents lie beneath Yggdrasil "than any fool can imagine" and lists them as Ginn and Minn (possibly meaning Old Norse "land animal"[14]), which he describes as sons of Grafvitnir (Old Norse, possibly "ditch wolf"[15]), Grbakr (Old Norse "Greyback"[14]), Grafvllur (Old Norse, possibly "the one digging under the plain" or possibly amended as "the one ruling in the ditch"[15]), fnir (Old Norse "the winding one, the twisting one"[16]), and Svfnir (Old Norse, possibly "the one who puts to sleep = death"[17]), who Odin adds that he thinks will forever gnaw on the tree's branches.[13]

3 of 8

25.11.2009 19:30

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil

In stanza 35, Odin says that Yggdrasil "suffers agony more than men know", as a hart bites it from above, it decays on its sides, and Nhggr bites it from beneath.[18] In stanza 44, Odin provides a list of things that are what he refers to as the "noblest" of their kind. Within the list, Odin mentions Yggdrasil first, and states that it is the "noblest of trees".[19]

Prose Edda

Yggdrasil is mentioned in two books in the Prose Edda, in Gylfaginning and Skldskaparml. In Gylfaginning, Yggdrasil is introduced in chapter 15. In chapter 15, Gangleri (described as king Gylfi in disguise) asks where is the chief or holiest place of the gods. High replies "It is the ash Yggdrasil. There the gods must hold their courts each day". Gangleri asks what there is to tell about Yggdrasil. Just-As-High says that Yggdrasil is the biggest and best of all trees, that its branches extend out over all of the world and reach out over the sky. Three of the roots of the tree support it, and these three roots also extend extremely far: one "is among the sir, the second among the frost jtnar, and the third over Niflheim. The root over Niflheim is gnawed at by the wyrm Nhggr, and beneath this root is the spring Hvergelmir. Beneath the root that reaches the frost jtnar is the well Mmisbrunnr, "which has wisdom and intelligence contained in it, and the master of the well is called Mimir". Just-As-High provides details regarding Mmisbrunnr and then describes that the third root of the well "extends to heaven" and that beneath the root is the "very holy" well Urarbrunnr. At Urarbrunnr the gods hold their court, and every day the sir ride to Urarbrunnr up over the bridge Bifrst. Later in the chapter, a stanza from Grmnisml mentioning Yggdrasil is quoted in support.[20] In chapter 16, Gangleri asks "what other particularly notable things are there to tell about the ash?" High says there is quite a lot to tell about. High continues that an eagle sits on the branches of Yggdrasil and that it has much knowledge. Between the eyes of the eagle sits a hawk called Verflnir. A squirrel called Ratatoskr scurries up and down the ash Yggdrasil carrying "malicious messages" between the eagle and Nhggr. Four stags named Dinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr, and Durarr run between the branches of Yggdrasil and consume its foilage. In the spring Hvergelmir are so many snakes along with Nhggr "that no tongue can enumerate them". Two stanzas from Grmnisml are then cited in support. High continues that the norns that live by the holy well Urarbrunnr each day take water from the well and mud from around it and pour it over Yggdrasil so that the branches of the ash do not rot away or decay. High provides more information about Urarbrunnr, cites a stanza from Vlusp in support, and adds that dew falls from Yggdrasil to the earth, explaining that "this is what people call honeydew, and from it bees feed".[21]

The title page of Olive Bray's 1908 translation of the Poetic Edda by W. G. Collingwood.

The norns Urr, Verandi, and Skuld beneath the world tree Yggdrasil (1882) by Ludwig Burger.

In chapter 41, the stanza from Grmnisml is quoted that mentions that Yggdrasil is the foremost of trees.[22] In chapter 54, as part of the events of Ragnark, High describes that Odin will ride to the well Mmisbrunnr and consult Mmir on behalf of himself and his people. After this, "the ash Yggdrasil will shake and nothing will be unafraid in heaven or on earth", and then the sir and Einherjar will don their war gear and advance to the field of Vgrr. Further into the chapter, the stanza in Vlusp that details this sequence is cited.[23] In the Prose Edda book Skldskaparml, Yggdrasil receives a single mention, though not by name. In chapter 64, names for kings and dukes are given. "Illustrious one" is provided as an example, appearing in a

4 of 8

25.11.2009 19:30

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil

Christianity-influenced work by the skald Hallvarr Hreksblesi: "There is not under the pole of the earth [Yggdrasil] an illustrious one closer to the lord of monks [God] than you."[24]

Theories

Shamanic origins

Hilda Ellis Davidson comments that the existence of nine worlds around Yggdrasil is mentioned more than once in Old Norse sources, but the identity of the worlds is never stated outright, though it can be deduced from various sources. Davidson comments that "no doubt the identity of the This large tree in the Viking nine varied from time to time as the emphasis changed or new imagery Age verhogdal tapestries may arrived". Davidson says that it is unclear where the nine worlds are located be Yggdrasil with Gullinkambi in relation to the tree; they could either exist one above the other or on top.[25] perhaps be grouped around the tree, but there are references to worlds existing beneath the tree, while the gods are pictured as in the sky, a rainbow bridge (Bifrst) connecting the tree with other worlds. Davidson opines that "those who have tried to produce a convincing diagram of the Scandinavian cosmos from what we are told in the sources have only added to the confusion". [26] Davidson notes parallels between Yggdrasil and shamanic lore in northern Eurasia:

[...] the conception of the tree rising through a number of worlds is found in northern Eurasia and forms part of the shamanic lore shared by many peoples of this region. This seems to be a very ancient conception, perhaps based on the Pole Star, the centre of the heavens, an the image of the central tree in Scandinavia may have been influenced by it [...]. Among Siberian shamans, a central tree may be used as a ladder to ascend the heavens [...].[26]

Davidson says that the notion of an eagle atop a tree and the world serpent coiled around the roots of the tree has parallels in other cosmologies from Asia. He goes on to say that Norse cosmology may have been influenced by these Asiatic cosmologies from a northern location. Davidson adds, on the other hand, that it is attested that the Germanic peoples worshiped their deities in open forest clearings and that a sky god was particularly connected with the oak tree, and therefore "a central tree was a natural symbol for them also".[26]

Mmameir, Hoddmmis holt and Ragnark

5 of 8

25.11.2009 19:30

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil

Connections have been proposed between the wood Hoddmmis holt (Old Norse "Hoard-Mmir's"[27] holt) and the tree Mmameir ("Mmir's tree"), generally thought to refer to the world tree Yggdrasil, and the spring Mmisbrunnr.[27] John Lindow concurs that Mmameir may be another name for Yggdrasil and that if the Hoard-Mmir of the name Hoddmmis holt is the same figure as Mmir (associated with the spring named after him, Mmisbrunnr), then the Mmir's holtYggdrasiland Mmir's spring may be within the same proximity.[28] Carolyne Larrington notes that it is nowhere expressly stated what will happen to Yggdrasil during the events of Ragnark. Larrington points to a connection between the primordial figure of Mmir and Yggdrasil in the poem Vlusp, and theorizes that "it is possible that Hoddmimir is another name for Mimir, and that the two survivors hide in Yggdrasill."[29]

Lf and Lfrasir after emerging from Hoddmmis holt (1895) by Lorenz Frlich

Rudolf Simek theorizes that the survival of Lf and Lfrasir through Ragnark by hiding in Hoddmmis holt is "a case of reduplication of the anthropogeny, understandable from the cyclic nature of the Eddic escatology." Simek says that Hoddmmis holt "should not be understood literally as a wood or even a forest in which the two keep themselves hidden, but rather as an alternative name for the world-tree Yggdrasill. Thus, the creation of mankind from tree trunks (Askr, Embla) is repeated after the Ragnar k as well." Simek says that in Germanic regions, the concept of mankind originating from trees is ancient. Simek additionally points out legendary parallels in a Bavarian legend of a shepherd who lives inside a tree, whose descendants repopulate the land after life there has been wiped out by plague (citing a retelling by F. R. Schrder). In addition, Simek points to an Old Norse parallel in the figure of rvar-Oddr, "who is rejuvenated after living as a tree-man ( rvar-Odds saga 2427)".[30]

Warden trees, Irminsul, and sacred trees

Continuing as late as the 19th century, warden trees were venerated in areas of Germany and Scandinavia, considered to be guardians and bringers of luck, and offerings were sometimes made to them. A massive birch tree standing atop a burial mound and located beside a farm in western Norway is recorded as having had ale poured over its roots during festivals. The tree was felled in 1874.[31]

A tree grows atop a Nordic Davidson comments that "the position of the tree in the centre as a source Bronze Age burial mound in of luck and protection for gods and men is confirmed" by these rituals to Roskilde, Denmark. Warden Trees. Davidson notes that the gods are described as meeting beneath Yggdrasil to hold their things, and that the pillars venerated by the Germanic peoples, such as the pillar Irminsul, were also symbolic of the center of the world. Davidson details that it would be difficult to ascertain whether a tree or pillar came first, and that this likely depends on if the holy location was in a thickly wooded area or not. Davidson notes that there is no mention of a sacred tree at ingvellir in Iceland yet that Adam of Bremen describes a huge tree standing next to the Temple at Uppsala in Sweden, which Adam describes as remaining green throughout summer and winter, and that no one knew what type of tree it was. Davidson comments that while it is uncertain that Adam's informant actually witnessed that the tree's type is unknown, the existence of sacred trees in pre-Christian Germanic Europe is further evidenced by records of their destruction by early Christian missionaries, such as Thor's Oak by Saint Boniface.[31]

Ken Dowden comments that behind Irminsul, Thor's Oak in Geismar, and the sacred tree at Uppsala "looms a mythic prototype, an Yggdrasil, the world-ash of the Norsemen".[32]

6 of 8

25.11.2009 19:30

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil

Modern influence

The world ash Ygdrasil (as Richard Wagner spelled it) appears in the ominous opening scene of Gtterdmmerung, in which the three Norns tell how Wotan had long ago broken off a branch to fashion himself the spear that gave him mastery over men and gods, and in which Wotan soon comes to wake Erda, Mother Earth, from her sleep with urgent questioning. Modern works of art depicting Yggdrasil include Die Nornen (painting, 1888) by K. Ehrenberg; Yggdrasil (fresco, 1933) by Axel Revold, located in the University of Oslo library auditorium in Oslo, Norway; Hjortene beiter i lvet p Yggdrasil asken (wood relief carving, 1938) on the Oslo City Hall by Dagfin Werenskjold; and the bronze relief on the doors of the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities (around 1950) by B. Marklund in Stockholm, Sweden. Poems mentioning Yggdrasil include Vrdtrdet by Viktor Rydberg and Yggdrasill by J. Linke.[33]

See also

Category:Trees in Germanic paganism

Notes

1. ^ a b c d Simek (2007:375) 2. ^ Yggdrasil (http://education.yahoo.com/reference /dictionary/entry/Yggdrasil) in the American Heritage Dictionary 3. ^ "Yggdrasil" Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2009. (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary /Yggdrasil) 4. ^ Yggdrasill (http://www.britannica.com /EBchecked/topic/653137/Yggdrasill) in Encyclopdia Britannica 5. ^ Some dictionaries list only the pronunciation / g.dr .s l/, for example Merriam-Webster, but the American Heritage Dictionary also lists IPA: [ y .dr .sil] as a second variant. 6. ^ Dronke (1997:7). 7. ^ Dronke (1997:1112). 8. ^ Dronke (1997:12). 9. ^ Dronke (1997:14). 10. ^ Dronke (1997:19). 11. ^ a b Larrington (1999:34). 12. ^ Lindow (2001:321). 13. ^ a b c Larrington (1999:56). ^ a b Simek (2007:115). ^ a b Simek (2007:116). ^ Simek (2007:252). ^ Simek (2007:305). ^ Larrington (1999:57). ^ Larrington (1999:58). ^ Faulkes (1995:17). ^ Faulkes (1995:1819). ^ Faulkes (1995:34). ^ Faulkes (1995:54). ^ Faulkes (1995:146). ^ Schn (2004:50). ^ a b c Davidson (1993:69). ^ a b Simek (2007:154). ^ Lindow (2001:179). ^ Larrington (1999:269). ^ Simek (2007:189). For Schrder, see Schrder (1931). 31. ^ a b Davidson (1993:170). 32. ^ Dowden (2000:72). 33. ^ Simek (2007:376). 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30.

References

Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1993). The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe (http://books.google.com /books?id=sWLVZN0H224C&printsec=frontcover& dq=The+Lost+Beliefs+of+Northern+Europe#v=onepage&q=&f=false) . Routledge. IBSN 0203408500 Dowden, Ken (2000). European Paganism: the Realities of Cult from Antiquity to the Middle Ages (http://books.google.com/books?id=b-QfhYxtKScC&printsec=frontcover& source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false) . Routledge. ISBN 0415120349 Dronke, Ursula (Trans.) (1997). The Poetic Edda: Volume II: Mythological Poems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198111819

7 of 8

25.11.2009 19:30

Yggdrasil - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil

Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0192839462 Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0 Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-4608-7616-3 Schn, Ebbe. (2004). Asa-Tors hammare, Gudar och jttar i tro och tradition. Flt & Hssler, Vrnamo. ISBN 91-89660-41-2 Schrder, F. R. (1931). "Germanische Schpfungsmythen" in Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift 19, pp. 126. Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0859915131

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yggdrasil" Categories: Locations in Norse mythology | Trees in Germanic paganism | Individual trees This page was last modified on 24 November 2009 at 18:42. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. See Terms of Use for details. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Contact us

8 of 8

25.11.2009 19:30

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Nine Realms in Norse Mythology: Yggdrasill, Is An ImmenseDocument8 pagesThe Nine Realms in Norse Mythology: Yggdrasill, Is An Immenselicarl benitoPas encore d'évaluation

- Jörmungandr: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument2 pagesJörmungandr: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchEduard Loberez Reyes100% (1)

- YggdrasilDocument2 pagesYggdrasilResearchingPubPas encore d'évaluation

- The Nine Worlds of Norse MythologyDocument6 pagesThe Nine Worlds of Norse MythologyAiram Cristine MargatePas encore d'évaluation

- The Myths of The Nordic Lands: Younger Edda, Which Were Compiled in Iceland During The Middle Ages. The EddasDocument11 pagesThe Myths of The Nordic Lands: Younger Edda, Which Were Compiled in Iceland During The Middle Ages. The EddasJosephine May PitosPas encore d'évaluation

- 666 Antichrist Revealed June 6 2006Document15 pages666 Antichrist Revealed June 6 2006Nyxstory0% (1)

- ValkyrieDocument7 pagesValkyrieandrewwilliampalileo@yahoocomPas encore d'évaluation

- Rainbows in MythologyDocument7 pagesRainbows in MythologyBoris Petrovic50% (2)

- MacCULLOCH, JOHN ARNOTT (1930) Eddic Mythology. CHAPTER 33 COSMOGONY AND THE DOOM OF THE GODSDocument53 pagesMacCULLOCH, JOHN ARNOTT (1930) Eddic Mythology. CHAPTER 33 COSMOGONY AND THE DOOM OF THE GODSAnthony McIvorPas encore d'évaluation

- Binding of Fenrir StoryDocument2 pagesBinding of Fenrir StoryMelgar Gerald LopezPas encore d'évaluation

- Norse Symbols and Their TranslationsDocument3 pagesNorse Symbols and Their Translationsceferli100% (1)

- Cover Letter For Community Mobilization OfficerDocument2 pagesCover Letter For Community Mobilization OfficerAftab Ahmad Mohal83% (24)

- The Snake-Witch Stone, Odhroerir Valhalla, and HeimdallDocument5 pagesThe Snake-Witch Stone, Odhroerir Valhalla, and HeimdallLyfingPas encore d'évaluation

- Yggdrasil (Norse Mythology)Document3 pagesYggdrasil (Norse Mythology)Hannah EnanodPas encore d'évaluation

- Norse MythologyDocument20 pagesNorse MythologyTUTUPas encore d'évaluation

- Name and Origin of YggdrasillDocument14 pagesName and Origin of YggdrasillDamon KiefferPas encore d'évaluation

- Microsoft Word ExerciseDocument2 pagesMicrosoft Word ExerciseGenesis Damaso100% (1)

- List of Valkyrie NamesDocument5 pagesList of Valkyrie Namesdzimmer6100% (3)

- Yggdrasil: Old Norse Cosmos Nine WorldsDocument25 pagesYggdrasil: Old Norse Cosmos Nine WorldsNick JbnPas encore d'évaluation

- The Nordic Gods: Måne and Natt Is One ExampleDocument11 pagesThe Nordic Gods: Måne and Natt Is One ExampleDocumentUploadPas encore d'évaluation

- Norse Mythology: A Guide to Norse Gods, Mythology, and FolkloreD'EverandNorse Mythology: A Guide to Norse Gods, Mythology, and FolklorePas encore d'évaluation

- Eagleton Terry What Is LiteratureDocument14 pagesEagleton Terry What Is LiteratureGeram Glenn Felicidario LomponPas encore d'évaluation

- VoluspaDocument8 pagesVoluspaRodney Mackay0% (1)

- The Tree of Life (Group 5Document24 pagesThe Tree of Life (Group 5Vhon Joseph SolomonPas encore d'évaluation

- Liturgical LanguageDocument7 pagesLiturgical LanguageSteve AnthonijszPas encore d'évaluation

- Norse Creation MythDocument3 pagesNorse Creation MythAlex DeVeiteoPas encore d'évaluation

- Norse Gods and Heroes - 1207102706Document12 pagesNorse Gods and Heroes - 1207102706Josephine May PitosPas encore d'évaluation

- Nordisk Mytologi: Norse Giants or JötunnDocument5 pagesNordisk Mytologi: Norse Giants or JötunnPatrick Lorente100% (1)

- Yggdrasil and The Well of UrdDocument5 pagesYggdrasil and The Well of UrdErnesto García100% (1)

- The Folklore of The Wild Hunt and The Furious HostDocument10 pagesThe Folklore of The Wild Hunt and The Furious Hostapi-3729826Pas encore d'évaluation

- On The Names For Wednesday in Germanic DialectsDocument14 pagesOn The Names For Wednesday in Germanic DialectsTiago CrisitanoPas encore d'évaluation

- DraugrDocument5 pagesDraugrWraiþūz KalletPas encore d'évaluation

- Delling RDocument4 pagesDelling Rdzimmer6Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ensayo Sobre GefjunDocument143 pagesEnsayo Sobre GefjunJhonMichaelPas encore d'évaluation

- Hrungnir's Heart and The ValknutDocument6 pagesHrungnir's Heart and The ValknutLyfing100% (1)

- Yggr's Horse: ' An Immense Tree in Norse Cosmology "Document1 pageYggr's Horse: ' An Immense Tree in Norse Cosmology "EduCationSuCKErsPas encore d'évaluation

- Palmerc MagazinespreadDocument1 pagePalmerc Magazinespreadapi-285956813Pas encore d'évaluation

- Please Read For A Very Good Description of The RealmsDocument3 pagesPlease Read For A Very Good Description of The RealmsJonsJJJPas encore d'évaluation

- Scandinavian SystemDocument12 pagesScandinavian Systemspake7Pas encore d'évaluation

- DagrDocument4 pagesDagrdzimmer6Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Yggdrasil GaeaDocument4 pages1 Yggdrasil Gaea29camziiPas encore d'évaluation

- GnosticRunes Notes Mythology2gDocument2 pagesGnosticRunes Notes Mythology2gMorten SchröderPas encore d'évaluation

- Norse CosmologyDocument5 pagesNorse CosmologydjakuyaPas encore d'évaluation

- L'origine Del Nome YggdrasillDocument14 pagesL'origine Del Nome Yggdrasillaurora porsennaPas encore d'évaluation

- Myrkviðr - WikipediaDocument3 pagesMyrkviðr - WikipediaIgor HrsticPas encore d'évaluation

- Presence LiteratureDocument4 pagesPresence LiteratureAtty FroiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Creation of The WorldDocument3 pagesThe Creation of The WorldJim DoddPas encore d'évaluation

- Norse PantheonDocument78 pagesNorse PantheonHemantPas encore d'évaluation

- Germania (Chapter 40), He Gives The Following Account of Seven SmallDocument100 pagesGermania (Chapter 40), He Gives The Following Account of Seven Smallaryeprakoso535Pas encore d'évaluation

- 00 Hildr Blog Notes and SourcesDocument11 pages00 Hildr Blog Notes and Sourcesmarnie_tunayPas encore d'évaluation

- HlínDocument3 pagesHlíndzimmer6Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 9 - RagnarokDocument3 pagesLecture 9 - RagnarokAlex McGintyPas encore d'évaluation

- YGGDRASILDocument4 pagesYGGDRASILOsiris28100% (1)

- Ash World TreeDocument18 pagesAsh World TreespunksuckerPas encore d'évaluation

- Edda - Man On The TreeDocument10 pagesEdda - Man On The TreemaaikejannamulderPas encore d'évaluation

- Hylestad Stave ChurchDocument3 pagesHylestad Stave Churchsanjo93Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dreams in Icelandic Tradition-Gabriel Turville-Petre PDFDocument12 pagesDreams in Icelandic Tradition-Gabriel Turville-Petre PDFPardiez7Pas encore d'évaluation

- Epic of GilgameshDocument6 pagesEpic of GilgameshEvelyn Calang EscobalPas encore d'évaluation

- The AnimalsDocument5 pagesThe AnimalsJanella PranadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Grendel and Berserkergang: Part I: Description of The BerserkrDocument19 pagesGrendel and Berserkergang: Part I: Description of The Berserkrjonh AlexanderPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 EtymDocument36 pages6 EtymAlessandra TacciniPas encore d'évaluation

- DMS Question PaperDocument16 pagesDMS Question PaperAmbika JaiswalPas encore d'évaluation

- 2nd Year Maths Chapter 1 Soulution NOTESPKDocument15 pages2nd Year Maths Chapter 1 Soulution NOTESPKFaisal RehmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Begging The QuestionDocument17 pagesBegging The QuestionNicole ChuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Present Simple WorkshopDocument2 pagesPresent Simple WorkshopnataliaPas encore d'évaluation

- Various PurposesDocument22 pagesVarious PurposesLJPas encore d'évaluation

- Exp 1,2 and 3Document9 pagesExp 1,2 and 3Shaikh InamulPas encore d'évaluation

- Social and Linguistic Diversity in Modern Britain Through The Contemporary Detective NovelDocument22 pagesSocial and Linguistic Diversity in Modern Britain Through The Contemporary Detective NovelGlobal Research and Development ServicesPas encore d'évaluation

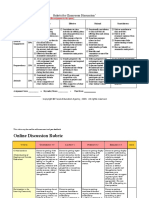

- ELC501 - Forum Discussion GuideDocument3 pagesELC501 - Forum Discussion GuideFaiz FahmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative AnalysisDocument33 pagesComparative AnalysisRimuel Salibio25% (4)

- My Sore Body Immediately Felt Refreshed.Document7 pagesMy Sore Body Immediately Felt Refreshed.vny276gbsbPas encore d'évaluation

- Da ResumeDocument3 pagesDa Resumeapi-534706203Pas encore d'évaluation

- Game Production Using Unity EditorDocument8 pagesGame Production Using Unity EditorRuhaan Choudhary0% (1)

- O Mankind Worship Your Lord AllaahDocument3 pagesO Mankind Worship Your Lord AllaahAminuPas encore d'évaluation

- MacroskillsDocument3 pagesMacroskillsItsmeKhey Phobe Khey BienPas encore d'évaluation

- Discussion Rubric ExamplesDocument6 pagesDiscussion Rubric ExamplesDilausan B MolukPas encore d'évaluation

- Iratj 08 00240Document6 pagesIratj 08 00240Noman Ahmed DayoPas encore d'évaluation

- CLP Talk 10 (Growing in The Spirit)Document48 pagesCLP Talk 10 (Growing in The Spirit)Ronie ColomaPas encore d'évaluation

- Getting Started With Nokia's Carbide - Vs 2.0 Development ToolsDocument19 pagesGetting Started With Nokia's Carbide - Vs 2.0 Development ToolsPraveen KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- As Per The Requirement of Neb Examination of Grade Xi Computer Science Based Project ON Report Generating System BATCH (2077, 2078)Document36 pagesAs Per The Requirement of Neb Examination of Grade Xi Computer Science Based Project ON Report Generating System BATCH (2077, 2078)PRANISH RAJ TULADHARPas encore d'évaluation

- SQL Topics: by Naresh Kumar B. NDocument9 pagesSQL Topics: by Naresh Kumar B. NKashyap MnvlPas encore d'évaluation

- Building Blocks & Trends in Data WarehouseDocument45 pagesBuilding Blocks & Trends in Data WarehouseRaminder CheemaPas encore d'évaluation

- DerivariDocument7 pagesDerivariGeorgiana RormanPas encore d'évaluation

- NCR FINAL Q3 ENG10 M1 ValDocument15 pagesNCR FINAL Q3 ENG10 M1 Valadditional accountPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sahapedia-UNESCO Project Fellowship 2019 Annexure IV: Description of DeliverablesDocument4 pagesThe Sahapedia-UNESCO Project Fellowship 2019 Annexure IV: Description of DeliverablesSurya GayathriPas encore d'évaluation

- 558279513-Unit 2.5 & ReviewDocument2 pages558279513-Unit 2.5 & ReviewAYJFPas encore d'évaluation