Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Radhika Singha...

Transféré par

Hema ChoudharyDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Radhika Singha...

Transféré par

Hema ChoudharyDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

As the title "From Faujdari to Faujdari Adalat: The Transition in Bengal" of this chapter suggests, the chapter mainly

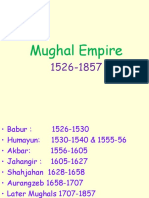

focused on the transition of judicial system from Mughal period to Early Colonial period in Bengal. Through the regulations of 1772, dual Govt. system was abolished and Bengal was brought under direct control of the British. The colonial state claimed exclusive rights to judicial and punitive authority as the prerogative of sovereignty. Both Hastings and Cornwallis claimed that they were restoring the 'ancient constitution in justice' with mere changes. .They suggest that Mughal agencies of justice had decayed because of the laxity and venality of regional rulers, whose powers had been usurped by zamindars and farmers of revenue. Hastings mainly focused on faujdar as the centralist aspects of Mughal order structure. In Mughal period, though the Mughal Emperors had absolute power, they appointed a number of officers in the different departments of the Govt. for the transaction of its multitudinous affairs. The next judicial authority was the qazi, who was appointed by the emperor. Qazis were assisted by muftis, whose main duty was to interpret the law and issue a fatwa. In the districts or Sarkars, law and order were maintained usually by officers like the Faujddars. "The faujddar, as his name suggests, was only the commander of a military force stationed in the country. He had to put down smaller rebellions, disperse or arrest robber gangs, take of all violent crimes, demonstrations of force to overawe, opposition to the revenue authorities, or the criminal judge, or the censor". The police arrangements were in some respects effective, though the State of public security varied greatly from place to place and from time to time. Mannuci reported that the faujdar was held responsible for robberies on travellers during the but if the traveller was robbed at night it was ascribed to his own negligence. During Mughal period, Personal dishonour was considered a powerful weapon, particularly effective at the upper levels of society. But the ruler still upheld his support for rank and social status, because the corporal forms of pain were usually reserved for the lower orders. In contrast to Akbar, Aurangzeb's political strategy, particularly after 1666, favoured a more clear-cut association with Muslim orthodox opinion, and an effort to stress the special status of Muslims under the Mughal imperium. Aurangzeb's appointment of muhtasibs in 1659 could be characterized as an

earlier gesture towards Islamic orthodoxy. Farman issued by Aurangzeb in 1672, again indicates that the emperor was trying to extend the prosecutorial initiative of the state. There were obvious advantages to having a body of case law to regularize this endeavour. Aurangzeb's farman emphasized on the importance of regularity in the disposal of cases. The order did not insist that the kazi and mufti alone were to determine the punishment of every offender, but that 'what the Nazim of the Subah decides should be done in accord with the judges. The farman also orders the punishment of anyone who strangled people for their property, not only if his guilt was proved by sharia law, but also if he was 'notorious among the people for this misdeed', or 'if the Nazim of the Subah and the judges believed that the misdeed was committed by him'. By the 18th century the Mughal state was unable to maintain a balance between its own agencies on the one hand and local rural and urban notables on the other. As the faujdari network on the highways weakened, local zamindars and Mughal satraps positioned themselves as the dispensers of 'justice and protection', levying fees and fines in this capacity. The decline of Mughal agencies did not necessarily mean that no alternative arrangements for the dispensation of justice and the maintenance of order took shape. With the decline of Mughal period there were the rise in regional successor states. However, even under the Nawabs of Bengal and Awadh, kazis and muftis could lose their authority in urban administration to revenue farmers and other 'new men' favoured by the regime. Under all the successor states, however, kazis and muftis retained their significance as local notables who could speak on behalf of the resident Muslim community, and as members of the respectable landholding section of society. According to the Author, the position of the kazi, mufti and muhtasib in the administrative hierarchy was more vulnerable to these changes than that of the kotwal. The transition to Company rule in Bengal has been dealt with in formidable depth. The faujdari adalats established in each district by the regulations of 1772 were supposed to gather up the judicial powers 'usurped' by the zamindars and revenue farmers. The regulations prohibited commissions on money recovered, fees on the decision of causes, and all 'heavy and arbitrary fines'. The reforms of 1772 included one significant foray into substantive law, in the form of Article 35,

for punishing dacoits. In the Council of 10 July 1773, Hastings suggests that the kazis and muftis of the faujdari adalats were not using Article 35 very enthusiastically. Hastings, had argued that it was die natural right of Indians to be ruled by the laws and customs with which they were familiar and that these laws were not antithietical to reason, humanity and natural justice. In maintaining that the doctrines of Hinduism or Islam contained the same truths which made up the universal nature of man, Orientalist scholars provided arguments for the feasibility of establishing dominion on the basis of the laws and customs of die Indian people. The judicial plan of 1772 evolved by Hastings and the Council had its critics within the Bengal establishment. Thomas Law and Cornwallis also wanted to rehabilitate the zamindars as improving property owners, but without any feudal authority in the matter of criminal jurisdiction. CONCLUSION:The changes introduced to conceptions of sovereignty and property right had repercussions for the agencies of governance. The loose inter-dependency of official and non-official agencies which author have described for the Mughal and 18th century regimes gradually developed towards more bureaucrarized hierarchies which centralized military and judicial functions and separated them from property relations. The Hastings Plan of 1772 established a hierarchy of civil and criminal courts, which were charged with the task of applying indigenous legal norms in all suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste, and other religious usages or institutions. Indigenous norms comprised the laws of the Koran with respect to Muhammadans, and the laws of the Brahmanic Shasters with respect to Hindus.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Legal System in Mughal IndiaDocument26 pagesLegal System in Mughal IndiaNisseem Krishna100% (1)

- Century Old Legal System: Whether Change Necessary or Not: Topics of The AssignmentDocument17 pagesCentury Old Legal System: Whether Change Necessary or Not: Topics of The AssignmentCharming MakaveliPas encore d'évaluation

- Thuggee' and The Margins of The State in Early Nineteenth-Century Colonial IndiaDocument25 pagesThuggee' and The Margins of The State in Early Nineteenth-Century Colonial Indiaar15t0tlePas encore d'évaluation

- Anglo Muhammadan LawDocument41 pagesAnglo Muhammadan LawSridutta dasPas encore d'évaluation

- Asian History: Encyglopedía OFDocument4 pagesAsian History: Encyglopedía OFRohit OberaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Evaluation of Mughal Judicial SytemDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Mughal Judicial SytemXYZPas encore d'évaluation

- 20010223063-History IiDocument4 pages20010223063-History IiTanushree GhoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Anglo-Mohammedan and Anglo-Hindu Law-Revisiting Colonial CodificationDocument22 pagesAnglo-Mohammedan and Anglo-Hindu Law-Revisiting Colonial CodificationRafsan JamanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bangladesh University of Professionals: AssignmentDocument7 pagesBangladesh University of Professionals: AssignmentTanjina IslamPas encore d'évaluation

- History ProjectDocument12 pagesHistory ProjectMaya GautamPas encore d'évaluation

- KÜRK. Hatice Büşra. IDTDocument12 pagesKÜRK. Hatice Büşra. IDThaticebusrakurkPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Legal SystemDocument20 pagesIndian Legal SystemSAJAD MOHAMMEDPas encore d'évaluation

- Law and Custom Divide: The Construct of Hindu Law in Colonial IndiaDocument10 pagesLaw and Custom Divide: The Construct of Hindu Law in Colonial IndiaAazam Abdul NistharPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Draft (History)Document18 pagesFinal Draft (History)Yash BhatnagarPas encore d'évaluation

- South Asian Legal Traditions PDFDocument15 pagesSouth Asian Legal Traditions PDFAhmed SiyamPas encore d'évaluation

- Mingqing GovernmentDocument7 pagesMingqing GovernmentJenny WangPas encore d'évaluation

- History I ProjectDocument14 pagesHistory I Projectayush2657Pas encore d'évaluation

- Judicial Administration During Medieval IndiaDocument4 pagesJudicial Administration During Medieval IndiaGaurav SokhiPas encore d'évaluation

- CC12 Module3Document6 pagesCC12 Module3Chandra Prakash DixitPas encore d'évaluation

- Islamic Law 2017Document30 pagesIslamic Law 2017Mumtaz Begam Abdul Kadir100% (1)

- Journal On Indian Penal CodeDocument7 pagesJournal On Indian Penal CodeNADEEM KHALIQPas encore d'évaluation

- Constituted: Lord CornwallisDocument1 pageConstituted: Lord CornwallisFamia AzkaPas encore d'évaluation

- Akbar and The Mughal State Edited PDFDocument36 pagesAkbar and The Mughal State Edited PDFNanang NurcholisPas encore d'évaluation

- Criminal Law in Ancient, Medieval and Modern TimesDocument15 pagesCriminal Law in Ancient, Medieval and Modern TimesRvi MahayPas encore d'évaluation

- TAYLOR-2011-Ottoman Governance in Seventeenth-Century Damascus PDFDocument269 pagesTAYLOR-2011-Ottoman Governance in Seventeenth-Century Damascus PDFGerald SackPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. Shahdeen MalikDocument31 pagesDr. Shahdeen MalikMd Mohashin RezaPas encore d'évaluation

- British Judicial InterventionDocument24 pagesBritish Judicial InterventionSanskriti RazdanPas encore d'évaluation

- Kazak Stan Hukuku Ve Devlet Tar H (#669212) - 915234Document10 pagesKazak Stan Hukuku Ve Devlet Tar H (#669212) - 915234makisima.19Pas encore d'évaluation

- Impeachment of JugdegsDocument10 pagesImpeachment of JugdegsvijayPas encore d'évaluation

- Ambiguity of Law 18th Century IndiaDocument5 pagesAmbiguity of Law 18th Century Indiasinidanapal1Pas encore d'évaluation

- G02106074354Document12 pagesG02106074354Abdullah BhattiPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 3 - Evolution of LawDocument13 pagesLesson 3 - Evolution of LawJelamie ValenciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Administrative System Under MughalsDocument2 pagesAdministrative System Under MughalsIsha SinhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kautilya Pov On Status of WomanDocument14 pagesKautilya Pov On Status of WomannitinPas encore d'évaluation

- Judicial System Under Muslim Rulers (1432)Document16 pagesJudicial System Under Muslim Rulers (1432)Charu SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Hindu Religious and Charitable EndowmentDocument23 pagesHindu Religious and Charitable EndowmentyuktiPas encore d'évaluation

- 7.1 Definition of Syariah and Islamic LawDocument20 pages7.1 Definition of Syariah and Islamic LawCalvin CJPas encore d'évaluation

- Adat Temenggung AssignmentsDocument10 pagesAdat Temenggung AssignmentsJane DeansPas encore d'évaluation

- Anglo Indian Leg Hgal SystemDocument3 pagesAnglo Indian Leg Hgal SystemArpeeta Shams MizanPas encore d'évaluation

- Islamic Legal System in Msia Farid SufianDocument29 pagesIslamic Legal System in Msia Farid SufianMichael JohnsonPas encore d'évaluation

- History Assignment-1Document14 pagesHistory Assignment-1Sharon JacobPas encore d'évaluation

- The History and Role of The Indian Penal Code inDocument8 pagesThe History and Role of The Indian Penal Code inShahzad SaifPas encore d'évaluation

- Jural - Colonization - of - India - and - Southeast - AsiaDocument25 pagesJural - Colonization - of - India - and - Southeast - AsiaYên ChiPas encore d'évaluation

- 1902 Order in Council ExplainedDocument3 pages1902 Order in Council ExplainedBALUKU JIMMYPas encore d'évaluation

- LAW: Instrument of Colonial IndiaDocument11 pagesLAW: Instrument of Colonial IndiaUnnayan ChandraPas encore d'évaluation

- The 12 Apostles of Russian Law: Lawyers who changed law, state and societyD'EverandThe 12 Apostles of Russian Law: Lawyers who changed law, state and societyPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Legal & Constitutional HistoryDocument10 pagesIndian Legal & Constitutional HistoryMADHURI ALLAPas encore d'évaluation

- Student Name: Sumi Akter Student ID: 193003053Document5 pagesStudent Name: Sumi Akter Student ID: 193003053Abdullah Al MasumPas encore d'évaluation

- Ancient Period:: 1. The Origin of Administrative Legal System ofDocument3 pagesAncient Period:: 1. The Origin of Administrative Legal System ofAyesha RashidPas encore d'évaluation

- History of The Evolution of Muslim Personal Law - K. K. Abdul RahimanDocument16 pagesHistory of The Evolution of Muslim Personal Law - K. K. Abdul RahimanAnkit Yadav100% (1)

- 1942 - A. N. Poliak - The Influence of C Ingiz - Ān's Yāsa Upon The General Organization of The Mamlūk StateDocument16 pages1942 - A. N. Poliak - The Influence of C Ingiz - Ān's Yāsa Upon The General Organization of The Mamlūk Statefatih çiftçiPas encore d'évaluation

- Hindu Law and DharmaDocument9 pagesHindu Law and DharmaAhat SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To The Judicial System of Pakistan .Document3 pagesIntroduction To The Judicial System of Pakistan .Haseeb Akbar KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Gueno Countryside Land Regulation 2019Document8 pagesGueno Countryside Land Regulation 2019geralddsackPas encore d'évaluation

- The Colonial System of Power in TurkistanDocument25 pagesThe Colonial System of Power in TurkistanHALİM KILIÇPas encore d'évaluation

- Pakistan Judicial HistoryDocument51 pagesPakistan Judicial HistoryAshar SaleemPas encore d'évaluation

- Che Omar Che Soh V PPDocument3 pagesChe Omar Che Soh V PPNadia Ezzati نادية اززاتي67% (6)

- 06 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument43 pages06 - Chapter 1 PDFVignesh678Pas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of Personal Laws in India: MR R.P. Choudhary, Dept. of Law Dr. C.V. Raman University, BilaspurDocument4 pagesEvolution of Personal Laws in India: MR R.P. Choudhary, Dept. of Law Dr. C.V. Raman University, BilaspurSarika SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Law & History in Colonial IndiaDocument22 pagesLaw & History in Colonial IndiaPunishk HandaPas encore d'évaluation

- History - Social Formations in Pre - Modern IndiaDocument27 pagesHistory - Social Formations in Pre - Modern IndiaCandyCrüshSaga100% (1)

- Bhartiya Swatantrata SangramDocument17 pagesBhartiya Swatantrata Sangramkapilsharma41Pas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Skies. The Howard HodgkinDocument52 pagesIndian Skies. The Howard HodgkinPaco RoigPas encore d'évaluation

- Following Are Some of The Sources of Medieval Indian HistoryDocument43 pagesFollowing Are Some of The Sources of Medieval Indian HistoryReena MpsinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Alauddin KhiljiDocument23 pagesAlauddin KhiljiVikash Agarwal0% (1)

- The History of India As Told by Its Own Historians Volume VIIDocument621 pagesThe History of India As Told by Its Own Historians Volume VIIMeeta RajivlochanPas encore d'évaluation

- Mughal Empire 1526-1707Document19 pagesMughal Empire 1526-1707navin jollyPas encore d'évaluation

- 13 Glossary-3Document11 pages13 Glossary-3sulemanPas encore d'évaluation

- Important FileDocument109 pagesImportant FileSiddu PatilPas encore d'évaluation

- History McqsDocument3 pagesHistory McqsFaisal MehmoodPas encore d'évaluation

- MODERN INDIA Revision Notes j1hhcgDocument165 pagesMODERN INDIA Revision Notes j1hhcgDhanush VasudevanPas encore d'évaluation

- From (Divyanshu Rai (Divyanshu.r31@gmail - Com) ) - ID (245) - History-1Document15 pagesFrom (Divyanshu Rai (Divyanshu.r31@gmail - Com) ) - ID (245) - History-1Raqesh MalviyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mewar Maharana Udai SinghDocument2 pagesMewar Maharana Udai SinghMohit RajaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Medicinal Practices in Mughal IndiaDocument6 pagesMedicinal Practices in Mughal IndiaArchi BiswasPas encore d'évaluation

- Sources of Maratha HistoryDocument309 pagesSources of Maratha HistoryAjay_Ramesh_Dh_6124100% (6)

- Section 1 QuestionsDocument5 pagesSection 1 QuestionsMahroush MahmudPas encore d'évaluation

- Marathas Mysore 78Document25 pagesMarathas Mysore 78nehaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2806 Part A DCHB Rangareddy PDFDocument900 pages2806 Part A DCHB Rangareddy PDFtejaswiniPas encore d'évaluation

- Floriculture - I XI PDFDocument144 pagesFloriculture - I XI PDFGkPas encore d'évaluation

- Shivaji and His TimesDocument490 pagesShivaji and His Timessriyogi0% (1)

- Revision Assignment Class VII 2022-23Document5 pagesRevision Assignment Class VII 2022-23Neel ChachraPas encore d'évaluation

- Mughliyah Saltanat), Mug Hliyah Saltanat) : Romanized RomanizedDocument35 pagesMughliyah Saltanat), Mug Hliyah Saltanat) : Romanized RomanizedRaj KomolPas encore d'évaluation

- Babur - The First Mughal Emperor (1526-30)Document20 pagesBabur - The First Mughal Emperor (1526-30)Umair TahirPas encore d'évaluation

- History Sem. 2 Project - Mughal Land Revenue SystemDocument14 pagesHistory Sem. 2 Project - Mughal Land Revenue Systemankit_chowdhri100% (11)

- Daulat Rai - Sahibe Kamal Guru Gobind SinghDocument176 pagesDaulat Rai - Sahibe Kamal Guru Gobind SinghRanjeet100% (1)

- Pakistan Studies O LevelsDocument22 pagesPakistan Studies O LevelsZunaira SafdarPas encore d'évaluation

- 9 MughalsDocument29 pages9 Mughalsamrutha chiranjeeviPas encore d'évaluation

- History of India (University of Delhi) History of India (University of Delhi)Document5 pagesHistory of India (University of Delhi) History of India (University of Delhi)Coolgirl AyeshaPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 3Document14 pagesGroup 3FATHIMA NAJAPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit III Exam Study Guide - AP World HistoryDocument8 pagesUnit III Exam Study Guide - AP World HistoryShane TangPas encore d'évaluation