Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

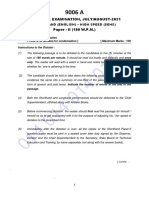

AU Liberation Theology 2

Transféré par

Mark HathawayDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

AU Liberation Theology 2

Transféré par

Mark HathawayDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

In the midst of the revolutionary fervour of the 1960s, Christians in Latin America began to rethink their role in projects

for social transformation. Even though the Catholic hierarchy had often been aligned with the ruling elites, other sectors of the church were already becoming agents for change. Christians became involved in struggles for land reform as well as movements like Catholic Action which encouraged commitment to progressive social movements. New ways of thinking emerged as church members began to reflect seriously upon the situation of poverty, repression, and exploitation that the majority of their people were living. In Biblical passages such as the account of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, they witnessed a God who struggled to liberate the oppressed from slavery. In Jesus teachings, as well, they saw how God showed a special concern for the poor, the powerless, and the marginalised. In 1968, the idea that the church should take a preferential option for the poor (though not yet framed in those words) strongly influenced the proceedings and documents of the Medelln meeting of Latin American Catholic bishops. Shortly afterwards, Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutirrez (who had been present at Medelln) published A Theology of Liberationconsidered the first major publication on liberation theology. Over the next decade, a wide number of books followed written by theologians such as Leonardo Boff (Brazil), Sergio Torres (Chile), Jon Sobrino (El Salvador), and Jos Miguez Bonino (Argentina). All shared a common methodology of reflecting biblically on the concrete situation and action of the poor struggling for liberation. To do so, they drew upon insights from the social sciences including the theory of dependency and Marxist analysis. During the seventiesa time when many nations in the region were governed by military dictatorshipsa new way of being church began to spread alongside liberation theology. Small grassroots Basic Christian Communities (BCCs)gathered to reflect on their own situation using the Bible as their central point of reference. Together, community members would plan actions to address the problems they confronted in their neighbourhoods and societies. In many places, these communities became important centres of political action, particularly where other spaces were closed due to repressive governments. In Brazil, for example, tens of thousands of BCCs eventually formed. Some members of BCCs became involved in armed struggles, particularly in Nicaragua and El Salvador. Most, though, expressed themselves through more non-violent forms of revolutionary struggle such as grassroots organisation, community projects, and protest marches. Growing numbers of religious, priests, and even bishops accompanied the communities in their struggles. As their commitment to the poor deepened, they began speaking out strongly in defence of those who suffered oppression and marginalization. The Catholic Latin American bishops conference held in Puebla in 1979 strongly affirmed both the preferential option for the poor and the promotion of BCCs. Soon, however, the project to build a liberatory church ran into opposition. Regimes throughout the continent as well as the United States opposed the movement through outright repression (including the torture and murder of church activists) or through support for conservative religious groups. By the 1980s, the Vatican also reacted by issuing proclamations

-2-

expressing its concern for the new theology and by replacing progressive bishops with more conservative ones. The growth of the new movement began to slow. By the end of the eighties, the collapse of real socialism in Europe and the Soviet Union was weakening the left in Latin America. At the same time, neoliberal economic reforms undermined many popular movements, particularly labour unions. The hopes for an imminent radical change in the region were fading. Because of this, liberation theology also entered into crisis. Even though Soviet-style communism had never been put forward as an ideal, the lack of an obvious alternative to capitalism nonetheless affected the dream of a new society with a cooperative, socialistic, and participatory vision at its core. Liberation theology today Despite these setbacks, neither liberation theology nor Basic Christian Communities have disappeared as a force in Latin America. Indeed, in recent years, liberation theology has been enriched by new perspectives coming from feminism, indigenous, and Afro-latino sources. In many ways, the critique of oppression has become richer as gender and race have been incorporated into the analysis of poverty. In the face of neoliberal economics, Latin American theologians have also began to speak in terms of a theology of the excluded in order to deal with the new economic reality: At the same time, liberation theology is attempting to integrate ecological perspectives into its thinking. There is even a concern to develop alternative ways of understanding the process of liberation and transformation based on insights from modern physics and cosmology. Liberation theology is also becoming increasingly ecumenical. While never exclusively a Catholic phenomenon, the consciousness of ecumenism was at times weak in the movement. This is changing as a new generation of progressive theologians is emerging in Latin Americas Protestant churches. Challenges Despite these advances, both liberation theology and Basic Communities still face many challenges. The time of hope which characterised the sixties and seventies has faded. What is the new utopia which can inspire social movements, both in the church and in society? How can the new perspectives be integrated to create a richer theory and practice of liberation? In particular, how can dimensions such as intuition, emotion, ritual, and art become part of a transformative praxis? Within the Catholic Church in particular, there are also limitation imposed by the failure of the institution to reform itself. New lay leaders have emerged from the Basic Communities, but church structures impede them from assuming the roles for which they are prepared: Women and married persons can only exercise limited ministries and few lay people teach in Catholic seminaries in the region. To a large extent, a new generation of liberation theologians have been frustrated by the lack of opportunity to employ and develop their gifts within the church. If liberation theology is to recover its place as a force for revolutionary renewal in Latin America, encouragement and support for grassroots theologians is essentialespecially for women, indigenous, and Afro-latinos.

-3-

Current importance While these challenges are both real and urgent, it is also evident that liberation theology will have a lasting impact upon both Christianity and social movements in Latin America. A surprising number of leaders of todays social movements and non-governmental organisations assumed their current commitments due to their involvement in Basic Christian Communities. Within the Catholic church, the bible has become a central point of reference. Lay persons are far more likely today to make their own faith decisions based on communal biblical reflection as opposed to simply obeying proclamations of the hierarchy. In effect, the grassroots Catholic church has moved much closer to traditional Protestant churches in this respect. There are positive indications that liberation theology will become a renewed force for change. A recent meeting of theologians in So Paulo, Brazil showed a growing creativity in liberation theologys way of thinking (see side bar). At the same time, there was a healthy awareness that the movement needs to revitalise itself and to incorporate new theologians. Hope was also expressed that ecology, feminism, and diverse non-Christian spiritualities can serve as a source for a new vision of radical transformation. If this happens, liberation theology may once again become an important an important source of inspiration for revolutionary social movements in Latin America. Side-Bar: Excerpts from the Final Document of the Meeting of Theologians Organised by the Collection Theology and Liberation in So Paulo Brazil, July 1997 On Neoliberalism We have witnessed deep transformation in the world scene, in the condition of the poor, and in the consciousness of the churches and theologians. We undoubtedly are living in a new human era with a global expression. This new era is characterised by the hegemony of neoliberalism and by the globalisation of markets whichby their competitive, non-cooperative natureproduce a devastating exclusion which harms the lives of the poor and the oppressed. On Popular Movements The popular movements which were so vibrant and strong at the birth of the [liberation theology] continue to exercise resistance, but they have also been significantly weakened, particularly in the area of labour organisations. Their projects are now fragmented and they experience great difficulties in formulating alternatives to this new form of global domination. On Ecological Concerns We see that the same logic which exploits the poorer classes and which dominates the nations also devastates the Earth along with all its riches To live an option for the poor today also implies living an option for greatest of all the poorour Mother Earth whose very survival is being threatened. On New Perspectives It is important to recognise that new expressions of liberation theology have emerged in recent years: cultural theology, indigenous theologies, black theologies, feminist theologies, and ecological liberation theology.

-4-

On Renewing Theology These challenges require serious reflection on the part of Christian churches and their theologians, both women and men. For this reason, we wish to translate our option for the poor and the excluded into a renewed liberatory theological endeavour. This project will be fundamentally ecumenical, in dialogue with new paradigms and new cosmovisions, and open to emerging themes. Through a process of frank dialogue, it will attempt to integrate the wisdom of our peoples with the great spiritual, religious, and humanistic traditions.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Engagement of Adolescents To Registration and VotingDocument5 pagesThe Engagement of Adolescents To Registration and VotingGeorgia RosePas encore d'évaluation

- Agrarian & Social Legislation Course at DLSUDocument7 pagesAgrarian & Social Legislation Course at DLSUAnonymous fnlSh4KHIgPas encore d'évaluation

- الأسرة الجزائرية والتغير الاجتماعيDocument15 pagesالأسرة الجزائرية والتغير الاجتماعيchaib fatimaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Indian Contract Act 1872: Essential Elements and Types of ContractsDocument3 pagesThe Indian Contract Act 1872: Essential Elements and Types of ContractsrakexhPas encore d'évaluation

- Media and Information Literacy: Quarter 3, Week 3 Types of Media: Print, Broadcast and New MediaDocument7 pagesMedia and Information Literacy: Quarter 3, Week 3 Types of Media: Print, Broadcast and New MediaIkay CerPas encore d'évaluation

- Maintaining momentum and ensuring proper attendance in committee meetingsDocument5 pagesMaintaining momentum and ensuring proper attendance in committee meetingsvamsiPas encore d'évaluation

- Mankin v. United States Ex Rel. Ludowici-Celadon Co., 215 U.S. 533 (1910)Document5 pagesMankin v. United States Ex Rel. Ludowici-Celadon Co., 215 U.S. 533 (1910)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Politics of Identity and The Project of Writing History in Postcolonial India - A Dalit CritiqueDocument9 pagesPolitics of Identity and The Project of Writing History in Postcolonial India - A Dalit CritiqueTanishq MishraPas encore d'évaluation

- Virginia Saldanha-Bishop Fathers Child by NunDocument17 pagesVirginia Saldanha-Bishop Fathers Child by NunFrancis LoboPas encore d'évaluation

- Rights of Minorities - A Global PerspectiveDocument24 pagesRights of Minorities - A Global PerspectiveatrePas encore d'évaluation

- The #MeToo Movement's Global ImpactDocument2 pagesThe #MeToo Movement's Global ImpactvaleriaPas encore d'évaluation

- Levent Bilman - Regional Initiatives in Southeast Europe and TurkeyDocument15 pagesLevent Bilman - Regional Initiatives in Southeast Europe and TurkeyAndelko VlasicPas encore d'évaluation

- Comrade Einstein Hello MathsDocument229 pagesComrade Einstein Hello MathsbablobkoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sahitya Akademi Award Tamil LanguageDocument5 pagesSahitya Akademi Award Tamil LanguageshobanaaaradhanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pak301 Assignment No 1Document2 pagesPak301 Assignment No 1Razzaq MalikPas encore d'évaluation

- Filed & Entered: Clerk U.S. Bankruptcy Court Central District of California by Deputy ClerkDocument6 pagesFiled & Entered: Clerk U.S. Bankruptcy Court Central District of California by Deputy ClerkChapter 11 DocketsPas encore d'évaluation

- Education AutobiographyDocument7 pagesEducation Autobiographyapi-340436002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Essay 1Document6 pagesEssay 1api-273268490100% (1)

- Day 3 AthensandspartaDocument23 pagesDay 3 Athensandspartaapi-265078501Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2300 Dutch Word Exercises - Rosetta WilkinsonDocument274 pages2300 Dutch Word Exercises - Rosetta WilkinsonVohlaPas encore d'évaluation

- Global - Rights - Responsibilities - Planet - DiversityDocument3 pagesGlobal - Rights - Responsibilities - Planet - DiversityVanessa CurichoPas encore d'évaluation

- Note On Amendment Procedure and Emergency ProvisionsDocument10 pagesNote On Amendment Procedure and Emergency ProvisionsGarima SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Nandinee (211839)Document17 pagesNandinee (211839)dattananddineePas encore d'évaluation

- Argosy November 3, 2011Document32 pagesArgosy November 3, 2011Geoff CampbellPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparison Between Formal Constraints and Informal ConstraintsDocument4 pagesComparison Between Formal Constraints and Informal ConstraintsUmairPas encore d'évaluation

- Cook, David (2011) Boko Haram, A PrognosisDocument33 pagesCook, David (2011) Boko Haram, A PrognosisAurelia269Pas encore d'évaluation

- Notes - Class - 10th - Social Science2023-24 KVSDocument55 pagesNotes - Class - 10th - Social Science2023-24 KVSsanjaymalakar087224100% (3)

- U.S Military Bases in The PHDocument10 pagesU.S Military Bases in The PHjansenwes92Pas encore d'évaluation

- Smias Ihtifal Ilmi 2020 English Debate Competition: Sekolah Menengah Islam As SyddiqDocument29 pagesSmias Ihtifal Ilmi 2020 English Debate Competition: Sekolah Menengah Islam As SyddiqArina Mohd DaimPas encore d'évaluation

- 04-22-14 EditionDocument28 pages04-22-14 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalPas encore d'évaluation