Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

How Much Does That Cost? The Numerology of The Consumer's Mind

Transféré par

Babu GeorgeDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

How Much Does That Cost? The Numerology of The Consumer's Mind

Transféré par

Babu GeorgeDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

How Much Does That Cost? The Numerology of the Consumers Mind So, is that a deal?

Who among us, including the super-gurus, has not wondered after seeing price tags highlighting discounts or product labels highlighting extra volume? At that point, no one can resist doing some quick math. However, the math in consumerology is class different from the math we are familiar in our everyday lives. Lets try to list some of the rules of this dark mathematics (remember, this is not a universal science and it doesnt always work!): 1. Theres no objective reference point and its all a matter of comparison. If McDonalds can offer a hot-n-spicy McChicken for $1, Burger King should not charge more than that for its similar burger. If McDonalds sold a hot-n-spicy McChicken for $1 last month (as part of a deal), it is unacceptable to pay $1.25 now (when the deal ended). In an electronic supermarket, there are two 72 television sets (equivalent in features) kept side by side; one costs $1500 and the other costs $1100. This mere fact of side by side positioning for comparison alone would increase the likelihood of sale of the $1200 TV set. Now, imagine, there was another similar TV set with a price tag of $1300. Ironically, this would reduce the sale of the $1100 TV set. Equity theory, originally developed to understand fairness and unfairness in human relations, tries to address these and related issues in consumer behavior. 2. Consumers tend to maintain balance in their attitude towards market offerings Balance theory conceptualizes the consistency motive as a drive toward psychological balance. So, if I do not like an energy drink but my favorite cricket demigod keeps on appearing in the commercials and endorsing it, I might begin to like it and possibly buy it for the sake of mental comfort generating out of consistency. 3. For consumers, percentage of increase in product quantity is equal to percentage of decrease in price A little math would tell you that 10% more Surf for the regular price is a lesser proposition for a consumer than 10% off from regular price for the regular weight. Most folks dont get it. Savvy marketers do exploit this weakness very often, though. 4. The unrecoverable illusion of the last cent Even the dumbest person now knows that selling a product for $9.99 is a trick to mislead him. But, who wants to ignite his precious mental fuel for just a cent! Or, for a dollar when it is $999 Vs. $1000. But, for marketers, many such drops constitute a river (of profit). It is interesting to note that the same consumer who exaggerates the value of $9.99 over $10 undermines the value of $2.859 over $2.85 (typically, in gas stations). 5. Shipping costs, handling costs, No! Consumers are more willing to pay an eBay seller $100 for a camera if shipping, handling, etc., are included in that price than if they were to pay $90 for the camera plus shipping and handling. Even

though a lower price might entice them in the initial stages, such arousal suddenly gives way for reason and the purchase may be deferred. Especially when it comes to recurrent purchases, people dont want to have hassles: Amazon, like many other vendors, understands this mentality very well and has extended their subscribe and save offers to a large range of products. Here, consumers forgo the potential benefits of price reductions in the future and the chance of being able to buy newer products of course, they are saved from potential price increases. On a similar note, how many of us buy things just because we have a coupon or our credit cards offer miles or cash back for that purchase! 6. Outliers generate suspicion If a product is priced too low or too high in comparison with the other products meeting similar needs (whose prices revolve around an average), that generates credibility issues. In rare cases, overpricing might give the indication that a product is actually better (or, prestigious) than its competition. However, it is not for everyone and definitely this position cannot be achieved by overpricing overnight. Similarly, underpricing beyond a level is useless and might have the harmful implication of unacceptable quality. 7. Rebates and the magic of potential savings Many products are price tagged to reflect the final price after rebates meaning, the price discount he gets months after the consumer (potentially) fills out a lengthy form and mail it to the marketer. Remember, no emailing option or online forms for this. It would be interesting to research what percentage of buyers actually does this to save money. Yes, your loss is my gain! In many instances, addon warranty offers serve the same purpose. Car rental companies exploit a slightly different version of this strategy by scaring renters to buy their add-on insurance policies. Many employers know how the benefit of low premium multi-million life insurance policies can be used to increase the perceived value of their job offers. 8. Loosen the brains of your customers Loosely speaking, this is called the inversion of self. If you can trigger the playful brain of your customer, reason will take a nap. Make them buy your product when that happens. A touristy environment, alcohol, weed, etc., do this task very well. Door to door salesmen would tell you that it is easier to make sales in the afternoon than in the morning: the likely reason is that people are generally tired in the afternoons and wont apply similar intensity of thinking than if they were to buy the same product in the morning. Nothing mentioned above is written with the intention of tarnishing the buyer. In fact, no transaction takes place until the buyer and the seller agrees for a relationship whose embodification the agreed upon price is. Most buyers do go through a short phase of cognitive dissonance, but that is ephemeral at best. An iPhone buyer who paid $500 on the first day of its sale might not be dumber than another who got it for $250 after a year. They are not meeting the same river, for sure. In the ultimate analysis, satisfaction as a sense of achievement is purely subjective.

And there are many more. But, despite all that we know about the consumer psyche, our ability to manage it is still abysmally poor. May be, what we know is just the tip of an iceberg. Finally, can someone answer why Coke would price two half liter bottles together for $1.99 and one 1 liter bottle for $2.49? Or, why McDonalds would run the promotion of two McKinley sandwiches for $2.25 and one for $2.50?

Babu George The author is an associate professor of business administration in Alaska Pacific University, USA, and may be contacted at bgeorge@alaskapacific.edu

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- GKN Case Study: Global High-Tech Manufacturer Aligns Workforce Processes Using SumTotalDocument2 pagesGKN Case Study: Global High-Tech Manufacturer Aligns Workforce Processes Using SumTotalSumTotal Talent ManagementPas encore d'évaluation

- 2018 Global Assessment Trends Report en PDFDocument40 pages2018 Global Assessment Trends Report en PDFstanleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Trainee Train Guard: Information PackDocument22 pagesTrainee Train Guard: Information PackstanleyPas encore d'évaluation

- Channel StrategyDocument95 pagesChannel StrategyEllur Anand0% (1)

- 2014 BrandZ Top100 ReportDocument72 pages2014 BrandZ Top100 ReportSrinivasan PusuluriPas encore d'évaluation

- DDB YP UnleashEmotions 040907Document5 pagesDDB YP UnleashEmotions 040907MarinaMonteiroGarciaPas encore d'évaluation

- Accounting and Finance For The International Hospitality Industry PDFDocument319 pagesAccounting and Finance For The International Hospitality Industry PDFGede Panca Ady SapputraPas encore d'évaluation

- ZaraDocument6 pagesZaraSridip Adhikary100% (1)

- Deming's Contribution To TQMDocument7 pagesDeming's Contribution To TQMMythily VedhagiriPas encore d'évaluation

- The New Consumers: The Influence Of Affluence On The EnvironmentD'EverandThe New Consumers: The Influence Of Affluence On The EnvironmentPas encore d'évaluation

- Techniques of Work With The Public: - Organization of "Pseudo"/media/-EventsDocument10 pagesTechniques of Work With The Public: - Organization of "Pseudo"/media/-EventsRajanRanjanPas encore d'évaluation

- TTQTDocument24 pagesTTQTXu XuPas encore d'évaluation

- Cabelas Case Study: Cabela's Delivers Knowledge and Training To Retail LocationsDocument2 pagesCabelas Case Study: Cabela's Delivers Knowledge and Training To Retail LocationsSumTotal Talent ManagementPas encore d'évaluation

- Boiling Point? The Skills Gap in US ManufacturingDocument16 pagesBoiling Point? The Skills Gap in US ManufacturingDeloitte AnalyticsPas encore d'évaluation

- Effective Interviewing Skills:: A Self-Help GuideDocument29 pagesEffective Interviewing Skills:: A Self-Help Guideaqas_khanPas encore d'évaluation

- Successful Interviewing: General GuidelinesDocument7 pagesSuccessful Interviewing: General GuidelinesRajanRanjanPas encore d'évaluation

- SumTotal Strategic HCM BrochureDocument4 pagesSumTotal Strategic HCM BrochureSumTotal Talent ManagementPas encore d'évaluation

- Employee Engagement and Retention Survey in Ten CompanyDocument16 pagesEmployee Engagement and Retention Survey in Ten CompanypujanswetalPas encore d'évaluation

- Reliability Basics II Using FMRA To Estimate Baseline ReliabilityDocument10 pagesReliability Basics II Using FMRA To Estimate Baseline ReliabilityNdomaduPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Tips To Effective Succession PlanningDocument11 pages5 Tips To Effective Succession PlanningSumTotal Talent ManagementPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of ContractsDocument27 pagesTypes of ContractsWaelBouPas encore d'évaluation

- Estimating & TenderingDocument21 pagesEstimating & TenderingRajanRanjanPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 SelectionMethods 28pDocument28 pages07 SelectionMethods 28paqas_khanPas encore d'évaluation

- Tenaris University Case Study: Improving The Flexibility of Learning Management To Expand Its Reach and Meet Corporate Training ObjectivesDocument3 pagesTenaris University Case Study: Improving The Flexibility of Learning Management To Expand Its Reach and Meet Corporate Training ObjectivesSumTotal Talent ManagementPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Management Chap012Document49 pagesStrategic Management Chap012rizz_inkays100% (1)

- The Campaign FrameworkDocument11 pagesThe Campaign FrameworkgagansrikankaPas encore d'évaluation

- 50 Supermarket Tricks You Still Fall For (Maria Teresa) - 2 CÓPIASDocument5 pages50 Supermarket Tricks You Still Fall For (Maria Teresa) - 2 CÓPIASkikahtlPas encore d'évaluation

- Risk CategoriesDocument10 pagesRisk CategoriesJon TkelPas encore d'évaluation

- Enterprise Rent A CarDocument2 pagesEnterprise Rent A Cartushar3010Pas encore d'évaluation

- Build A Better B2B Customer Experience Program: Key ChallengesDocument10 pagesBuild A Better B2B Customer Experience Program: Key ChallengesFelipe HerediaPas encore d'évaluation

- A new era of Value Selling: What customers really want and how to respondD'EverandA new era of Value Selling: What customers really want and how to respondPas encore d'évaluation

- EnterpriseDocument10 pagesEnterprisebirinawaPas encore d'évaluation

- IPA Excellence Diploma - Module 2 - Brands and People - by Tom DarlingtonDocument11 pagesIPA Excellence Diploma - Module 2 - Brands and People - by Tom DarlingtontomdarlingtonPas encore d'évaluation

- Brand Aid Company. Intro. 8Document22 pagesBrand Aid Company. Intro. 8Itai TalmiPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 3 Personal FinanceDocument19 pagesModule 3 Personal FinanceJoana Marie CabutePas encore d'évaluation

- Seven Billion BanksDocument12 pagesSeven Billion BanksmatijatransPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of Buying BehaviorDocument14 pagesTypes of Buying BehaviorJosh ChuaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pricing Ethics ReadingDocument4 pagesPricing Ethics Readingandres felipe oicata tibataPas encore d'évaluation

- 14 Useful Persuasion Techniques To Improve Sales (2023)Document9 pages14 Useful Persuasion Techniques To Improve Sales (2023)Rovin RamphalPas encore d'évaluation

- Marketing BF GkylylDocument14 pagesMarketing BF GkylylJosh ChuaPas encore d'évaluation

- A Consumer's Constrained ChoiceDocument33 pagesA Consumer's Constrained ChoiceMary Catherine Almonte - EmbatePas encore d'évaluation

- No-Harm Marketing Ethics: How to Attract Customers and Sell So You Still Like Yourself in the MorningD'EverandNo-Harm Marketing Ethics: How to Attract Customers and Sell So You Still Like Yourself in the MorningÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (1)

- Cognitive DissonanceDocument3 pagesCognitive Dissonancediptasreedebbarma5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Indirect AIDA Pattern of PersuasionDocument5 pagesIndirect AIDA Pattern of PersuasionRavi KediaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tactics You Can Use To Make A Customer Buy Again, and Again: Marketing6packDocument4 pagesTactics You Can Use To Make A Customer Buy Again, and Again: Marketing6packWASABIPas encore d'évaluation

- Perloff 3Document33 pagesPerloff 3Miguel AngelPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 5 Consumer StrategyDocument21 pagesModule 5 Consumer StrategySylvia TonogPas encore d'évaluation

- Grocery Couponing Secrets: How To Save Money on GroceriesD'EverandGrocery Couponing Secrets: How To Save Money on GroceriesÉvaluation : 1 sur 5 étoiles1/5 (1)

- NTRODUCTIONDocument8 pagesNTRODUCTIONros_verma07Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Price Is RightDocument9 pagesThe Price Is Rightisaac sojoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Psychology of Pricing: A Gigantic List of StrategiesDocument30 pagesThe Psychology of Pricing: A Gigantic List of StrategiesLuca FontaniPas encore d'évaluation

- How Do Retailers Know About Your Spending Habits?: Webroot Spy SweeperDocument5 pagesHow Do Retailers Know About Your Spending Habits?: Webroot Spy SweeperRooppreet KaurPas encore d'évaluation

- 8 Components IrresistibleDocument9 pages8 Components IrresistibleSamuel SouzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Decision Making in Consumer BehaviorDocument12 pagesDecision Making in Consumer BehaviorSanober Iqbal100% (1)

- Pricing As A StrategyDocument8 pagesPricing As A StrategycandyPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 Exaggerating BiasDocument2 pages07 Exaggerating Biasrameshlkumkar34987Pas encore d'évaluation

- Manage Price InflationDocument8 pagesManage Price InflationKrishnan SampathPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Decision Making Module 5Document15 pagesConsumer Decision Making Module 5abhishekmalusare07Pas encore d'évaluation

- DBA Thesis of Babu GeorgeDocument91 pagesDBA Thesis of Babu GeorgeBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- The 7 Deadly SinsDocument10 pagesThe 7 Deadly SinsBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Babu George Laureate Education Program Participation CertificateDocument1 pageBabu George Laureate Education Program Participation CertificateBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Tourism Marketing Case Studies - Alexandru Nedelea and Babu GeorgeDocument261 pagesTourism Marketing Case Studies - Alexandru Nedelea and Babu GeorgeBabu George50% (2)

- Proposal To Launch An E-MBA in Strategic Leadership Program Under NITTE University: A Concept Note. Draft Initiated by Dr. Babu George, NITTEDocument3 pagesProposal To Launch An E-MBA in Strategic Leadership Program Under NITTE University: A Concept Note. Draft Initiated by Dr. Babu George, NITTEBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Programme Ichss 2014 Budva - Montenegro (Blendi Shima and Babu George, SMC University)Document9 pagesProgramme Ichss 2014 Budva - Montenegro (Blendi Shima and Babu George, SMC University)Babu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Critical ThinkingDocument37 pagesCritical ThinkingBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Asian Management Review: January - March 2011Document6 pagesAsian Management Review: January - March 2011Babu George100% (1)

- Developing A Strong Research Culture in The Business SchoolDocument2 pagesDeveloping A Strong Research Culture in The Business SchoolBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Evaluation of BAM 499Document3 pagesEvaluation of BAM 499Babu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- CORPORATE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: An Innovative Strategic Solution For Global CompetitivenessDocument9 pagesCORPORATE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: An Innovative Strategic Solution For Global CompetitivenessBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- BAM 499 RubricDocument3 pagesBAM 499 RubricBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- International Tourism: World Geography and Developmental PerspectivesDocument128 pagesInternational Tourism: World Geography and Developmental PerspectivesBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Peace Through Alternative Tourism: Case Studies From Bengal, IndiaDocument21 pagesPeace Through Alternative Tourism: Case Studies From Bengal, IndiaBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction of Casino Gaming in Okinawa, Japan: A Case Study of Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument21 pagesIntroduction of Casino Gaming in Okinawa, Japan: A Case Study of Challenges and OpportunitiesBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Medical Tourism in India: A Case Study of Apollo HospitalsDocument11 pagesMedical Tourism in India: A Case Study of Apollo HospitalsBabu George88% (8)

- Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Africa: Insights For Modern Management PracticeDocument14 pagesIndigenous Knowledge Systems in Africa: Insights For Modern Management PracticeBabu GeorgePas encore d'évaluation

- Application of The Pareto Analysis in Project ManagementDocument5 pagesApplication of The Pareto Analysis in Project Managementahmed anmarPas encore d'évaluation

- Bollier David Helfrich Silke The Wealth of The Commons A WorldDocument573 pagesBollier David Helfrich Silke The Wealth of The Commons A WorldЕвгений ВолодинPas encore d'évaluation

- Irrevocable Corporate Purchase Order (Icpo/Loi) For: Contract 12 MonthsDocument4 pagesIrrevocable Corporate Purchase Order (Icpo/Loi) For: Contract 12 MonthsjungPas encore d'évaluation

- Mariel Princess TabilangonDocument2 pagesMariel Princess TabilangonMariel PrincessPas encore d'évaluation

- 2012 Water Distribution Bulk Water Filling Station Bid Doc - 201205301523587116Document7 pages2012 Water Distribution Bulk Water Filling Station Bid Doc - 201205301523587116ayaz hasanPas encore d'évaluation

- Marks of A Successful EntrepreneurDocument4 pagesMarks of A Successful Entrepreneuremilio fer villaPas encore d'évaluation

- Applications of Business AnalyticsDocument10 pagesApplications of Business AnalyticsMansha YadavPas encore d'évaluation

- List of Table and Figures: Outline Development Plan, AgraDocument12 pagesList of Table and Figures: Outline Development Plan, AgrageetPas encore d'évaluation

- Session 3 - HGDG - PD and PIMMEDocument40 pagesSession 3 - HGDG - PD and PIMMEDr. Jose N. Rodriguez Memorial Medical Center100% (1)

- CHAPTER 1 - LatestDocument93 pagesCHAPTER 1 - LatestMOHAMAD ZAIM BIN IBRAHIM MoePas encore d'évaluation

- Digital Marketing Class NotesDocument58 pagesDigital Marketing Class Notestina tanwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Presentation 3Document8 pagesPresentation 3Anindita SinghviPas encore d'évaluation

- VrioDocument2 pagesVrioRoxana GabrielaPas encore d'évaluation

- Activity - 2 Entrep 1Document2 pagesActivity - 2 Entrep 1Christina AbelaPas encore d'évaluation

- All SD PacDocument5 pagesAll SD PacPat PowersPas encore d'évaluation

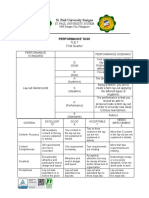

- St. Paul University Surigao: Performance TaskDocument2 pagesSt. Paul University Surigao: Performance TaskRoss Armyr Geli100% (1)

- Chapter 9 - Imperial, RisalieDocument14 pagesChapter 9 - Imperial, RisalieAmbray LynjoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Ratio Analysis: SBI Vs HDFC Bank Vs ICICI BankDocument18 pagesRatio Analysis: SBI Vs HDFC Bank Vs ICICI BankAbdulMullaPas encore d'évaluation

- The-AI-Ladder by IBMDocument27 pagesThe-AI-Ladder by IBMAnees Bee100% (1)

- Acg Module 9 Thc5-LathDocument10 pagesAcg Module 9 Thc5-LathMeishein FanerPas encore d'évaluation

- 17 Chemicals and Fertilizers 21Document100 pages17 Chemicals and Fertilizers 21JAYESH6Pas encore d'évaluation

- Blood Orange Sell SheetDocument4 pagesBlood Orange Sell SheetSunkist GrowersPas encore d'évaluation

- Pig FarmingDocument7 pagesPig FarmingAzure VMPas encore d'évaluation

- Swot Analysis of Revlon IncDocument5 pagesSwot Analysis of Revlon IncSubhana AsimPas encore d'évaluation

- OECD Measure Productivity 2001Document44 pagesOECD Measure Productivity 2001Binh ThaiPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal DheanDocument10 pagesJurnal DheandheanPas encore d'évaluation

- É Þé®Úé ) Åõ ºé Éçºéévéé®Úhé Éê É Éêxé Ééç Þ Êxévéò Êxé É ÉDocument115 pagesÉ Þé®Úé ) Åõ ºé Éçºéévéé®Úhé Éê É Éêxé Ééç Þ Êxévéò Êxé É ÉSHIVGOPAL KULHADEPas encore d'évaluation