Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Authentic Assessment: Arce, Carla Margarita C. Secondary Education - English IV

Transféré par

Carla ArceDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Authentic Assessment: Arce, Carla Margarita C. Secondary Education - English IV

Transféré par

Carla ArceDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Arce, Carla Margarita C.

Secondary Education English IV

Authentic assessment

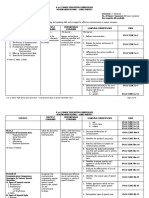

Authentic assessment refers to assessment tasks that resemble reading and writing in the real world and in school (Hiebert, Valencia & Afflerbach, 1994; Wiggins, 1993). Its aim is to assess many different kinds of literacy abilities in contexts that closely resemble actual situations in which those abilities are used. For example, authentic assessments ask students to read real texts, to write for authentic purposes about meaningful topics, and to participate in authentic literacy tasks such as discussing books, keeping journals, writing letters, and revising a piece of writing until it works for the reader. Both the material and the assessment tasks look as natural as possible. Furthermore, authentic assessment values the thinking behind work, the process, as much as the finished product (Pearson & Valencia, 1987; Wiggins, 1989; Wolf, 1989). Working on authentic tasks is a useful, engaging activity in itself; it becomes an "episode of learning" for the student (Wolf, 1989). From the teacher's perspective, teaching to such tasks guarantees that we are concentrating on worthwhile skills and strategies (Wiggins, 1989). Students are learning and practicing how to apply important knowledge and skills for authentic purposes. They should not simply recall information or circle isolated vowel sounds in words; they should apply what they know to new tasks. For example, consider the difference between asking students to identify all the metaphors in a story and asking them to discuss why the author used particular metaphors and what effect they had on the story. In the latter case, students must put their knowledge and skills to work just as they might do naturally in or out of school. Performance assessment is a term that is commonly used in place of, or with, authentic assessment. Performance assessment requires students to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and strategies by creating a response or a product (Rudner & Boston, 1994; Wiggins, 1989). Rather than choosing from several multiplechoice options, students might demonstrate their literacy abilities by conducting research and writing a report, developing a character analysis, debating a character's motives, creating a mobile of important information they learned, dramatizing a favorite story, drawing and writing about a story, or reading aloud a personally meaningful section of a story. For example, after completing a first-grade theme on families in which students learned about being part of a family and about the structure and sequence of stories, students might illustrate and write their own flap stories with several parts, telling a story about how a family member or friend helped them when they were feeling sad. The formats for performance assessments range from relatively short answers to long-term projects that require students to present or demonstrate their work. These performances often require students to engage in higher-order thinking and to integrate many language arts skills. Consequently, some performance assessments are longer and more complex than more traditional assessments. Within a complete assessment system, however, there should be a balance of longer performance assessments and shorter ones. Authentic assessments typically are criterion-referenced measures. That is, a student's aptitude on a task is determined by matching the student's performance against a set of criteria to determine the degree to which the student's performance meets the criteria for the task. To measure student performance against a predetermined set of criteria, a rubric, or scoring scale, is typically created which contains the essential criteria for the task and appropriate levels of performance for each criterion. For example, the following rubric (scoring scale) covers the research portion of a project: Research Rubric Criteria Number Sources Historical Accuracy Organization of 1 x1 1-4 x3 2 5-9 3 10-12 No apparent inaccuracies

Lots of historical Few inaccuracies inaccuracies tell

x1 Can not tell from Can

with Can easily tell which

Arce, Carla Margarita C. Secondary Education English IV

which source difficulty information came information from Bibliography

where sources info came drawn from

was

Bibiliography Bibliography All relevant x1 contains very little contains most information is information relevant information included

As in the above example, a rubric is comprised of two components: criteria and levels of performance. Each rubric has at least two criteria and at least two levels of performance. The criteria, characteristics of good performance on a task, are listed in the left-hand column in the rubric above (number of sources, historical accuracy, organization and bibliography). Actually, as is common in rubrics, the author has used shorthand for each criterion to make it fit easily into the table. The full criteria are statements of performance such as "include a sufficient number of sources" and "project contains few historical inaccuracies." For each criterion, the evaluator applying the rubric can determine to what degree the student has met the criterion, i.e., the level of performance. In the above rubric, there are three levels of performance for each criterion. For example, the project can contain lots of historical inaccuracies, few inaccuracies or no inaccuracies. Finally, the rubric above contains a mechanism for assigning a score to each project. (Assessments and their accompanying rubrics can be used for purposes other than evaluation and, thus, do not have to have points or grades attached to them.) In the second-to-left column a weight is assigned each criterion. Students can receive 1, 2 or 3 points for "number of sources." But historical accuracy, more important in this teacher's mind, is weighted three times (x3) as heavily. So, students can receive 3, 6 or 9 points (i.e., 1, 2 or 3 times 3) for the level of accuracy in their projects. Descriptors The above rubric includes another common, but not a necessary, component of rubrics --descriptors. Descriptors spell out what is expected of students at each level of performance for each criterion. In the above example, "lots of historical inaccuracies," "can tell with difficulty where information came from" and "all relevant information is included" are descriptors. A descriptor tells students more precisely what performance looks like at each level and how their work may be distinguished from the work of others for each criterion. Similarly, the descriptors help the teacher more precisely and consistently distinguish between student work. Many rubrics do not contain descriptors, just the criteria and labels for the different levels of performance. For example, imagine we strip the rubric above of its descriptors and put in labels for each level instead. Here is how it would look: Criteria Number of Sources Historical Accuracy Organization Bibliography x1 x3 x1 x1 Poor (1) Good (2) Excellent (3)

It is not easy to write good descriptors for each level and each criterion. So, when you first construct and use a rubric you might not include descriptors. That is okay. You might just include the criteria and some type of labels for the levels of performance as in the table above. Once you have used the rubric and identified student work that fits into each level it will become easier to articulate what you mean by "good" or "excellent." Thus, you might add or expand upon descriptors the next time you use the rubric.

Arce, Carla Margarita C. Secondary Education English IV

Why Include Levels of Performance? Clearer expectations As mentioned in Step 3, it is very useful for the students and the teacher if the criteria are identified and communicated prior to completion of the task. Students know what is expected of them and teachers know what to look for in student performance. Similarly, students better understand what good (or bad) performance on a task looks like if levels of performance are identified, particularly if descriptors for each level are included. More consistent and objective assessment In addition to better communicating teacher expectations, levels of performance permit the teacher to more consistently and objectively distinguish between good and bad performance, or between superior, mediocre and poor performance, when evaluating student work. Better feedback Furthermore, identifying specific levels of student performance allows the teacher to provide more detailed feedback to students. The teacher and the students can more clearly recognize areas that need improvement. Analytic Versus Holistic Rubrics For a particular task you assign students, do you want to be able to assess how well the students perform on each criterion, or do you want to get a more global picture of the students' performance on the entire task? The answer to that question is likely to determine the type of rubric you choose to create or use: Analytic or holistic. Analytic rubric Most rubrics, like the Research rubric above, are analytic rubrics. An analytic rubric articulates levels of performance for each criterion so the teacher can assess student performance on each criterion. Using the Research rubric, a teacher could assess whether a student has done a poor, good or excellent job of "organization" and distinguish that from how well the student did on "historical accuracy." Holistic rubric In contrast, a holistic rubric does not list separate levels of performance for each criterion. Instead, a holistic rubric assigns a level of performance by assessing performance across multiple criteria as a whole. For example, the analytic research rubric above can be turned into a holistic rubric: 3 - Excellent Researcher

included 10-12 sources no apparent historical inaccuracies can easily tell which sources information was drawn from all relevant information is included

2 - Good Researcher

included 5-9 sources few historical inaccuracies can tell with difficulty where information came from

Arce, Carla Margarita C. Secondary Education English IV

bibliography contains most relevant information

1 - Poor Researcher

included 1-4 sources lots of historical inaccuracies cannot tell from which source information came bibliography contains very little information

In the analytic version of this rubric, 1, 2 or 3 points is awarded for the number of sources the student included. In contrast, number of sources is considered along with historical accuracy and the other criteria in the use of a holistic rubric to arrive at a more global (or holistic) impression of the student work. Another example of a holistic rubric is the "Holistic Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric" (in PDF) developed by Facione & Facione. When to choose an analytic rubric Analytic rubrics are more common because teachers typically want to assess each criterion separately, particularly for assignments that involve a larger number of criteria. It becomes more and more difficult to assign a level of performance in a holistic rubric as the number of criteria increases. For example, what level would you assign a student on the holistic research rubric above if the student included 12 sources, had lots of inaccuracies, did not make it clear from which source information came, and whose bibliography contained most relevant information? As student performance increasingly varies across criteria it becomes more difficult to assign an appropriate holistic category to the performance. Additionally, an analytic rubric better handles weighting of criteria. How would you treat "historical accuracy" as more important a criterion in the holistic rubric? It is not easy. But the analytic rubric handles it well by using a simple multiplier for each criterion. When to choose a holistic rubric So, when might you use a holistic rubric? Holistic rubrics tend to be used when a quick or gross judgment needs to be made. If the assessment is a minor one, such as a brief homework assignment, it may be sufficient to apply a holistic judgment (e.g., check, check-plus, or no-check) to quickly review student work. But holistic rubrics can also be employed for more substantial assignments. On some tasks it is not easy to evaluate performance on one criterion independently of performance on a different criterion. For example, many writing rubrics (see example) are holistic because it is not always easy to disentangle clarity from organization or content from presentation. So, some educators believe a holistic or global assessment of student performance better captures student ability on certain tasks. (Alternatively, if two criteria are nearly inseparable, the combination of the two can be treated as a single criterion in an analytic rubric.)

How Many Levels of Performance Should I Include in my Rubric? There is no specific number of levels a rubric should or should not possess. It will vary depending on the task and your needs. A rubric can have as few as two levels of performance (e.g., a checklist) or as many as ... well, as many as you decide is appropriate. (Some do not consider a checklist a rubric because it only has two levels -- a criterion was met or it wasn't. But because a checklist does contain criteria and at least two levels of performance, I include it under the category of rubrics.) Also, it is not true that there must be an even number or an odd number of levels. Again, that will depend on the situation. To further consider how many levels of performance should be included in a rubric, I will separately address analytic and holistic rubrics.

Arce, Carla Margarita C. Secondary Education English IV

Analytic rubrics Generally, it is better to start with a smaller number of levels of performance for a criterion and then expand if necessary. Making distinctions in student performance across two or three broad categories is difficult enough. As the number of levels increases, and those judgments become finer and finer, the likelihood of error increases. Thus, start small. For example, in an oral presentation rubric, amount of eye contact might be an important criterion. Performance on that criterion could be judged along three levels of performance: never, sometimes, always. makes eye contact with audience never sometimes always

Although these three levels may not capture all the variation in student performance on the criterion, it may be sufficient discrimination for your purposes. Or, at the least, it is a place to start. Upon applying the three levels of performance, you might discover that you can effectively group your students' performance in these three categories. Furthermore, you might discover that the labels of never, sometimes and always sufficiently communicates to your students the degree to which they can improve on making eye contact. On the other hand, after applying the rubric you might discover that you cannot effectively discriminate among student performance with just three levels of performance. Perhaps, in your view, many students fall in between never and sometimes, or between sometimes and always, and neither label accurately captures their performance. So, at this point, you may decide to expand the number of levels of performance to include never, rarely, sometimes, usually and always. makes eye contact never rarely sometimes usually always

There is no "right" answer as to how many levels of performance there should be for a criterion in an analytic rubric; that will depend on the nature of the task assigned, the criteria being evaluated, the students involved and your purposes and preferences. For example, another teacher might decide to leave off the "always" level in the above rubric because "usually" is as much as normally can be expected or even wanted in some instances. Thus, the "makes eye contact" portion of the rubric for that teacher might be makes eye contact never rarely sometimes usually

So, I recommend that you begin with a small number of levels of performance for each criterion, apply the rubric one or more times, and then re-examine the number of levels that best serve your needs. I believe starting small and expanding if necessary is preferable to starting with a larger number of levels and shrinking the number because rubrics with fewer levels of performance are normally

easier and quicker to administer easier to explain to students (and others) easier to expand than larger rubrics are to shrink

The fact that rubrics can be modified and can reasonably vary from teacher to teacher again illustrates that rubrics are flexible tools to be shaped to your purposes. To read more about the decisions involved in developing a rubric, see the chapter entitled, "Step 4: Create the Rubric." Holistic rubrics

Arce, Carla Margarita C. Secondary Education English IV

Much of the advice offered above for analytic rubrics applies to holistic rubrics as well. Start with a small number of categories, particularly since holistic rubrics often are used for quick judgments on smaller tasks such as homework assignments. For example, you might limit your broad judgments to

satisfactory unsatisfactory not attempted

or

check-plus check no check

or even just

satisfactory (check) unsatisfactory (no check)

Of course, to aid students in understanding what you mean by "satisfactory" or "unsatisfactory" you would want to include descriptors explaining what satisfactory performance on the task looks like. Even with more elaborate holistic rubrics for more complex tasks I recommend that you begin with a small number of levels of performance. Once you have applied the rubric you can better judge if you need to expand the levels to more effectively capture and communicate variation in student performance.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Rubrics: Rubric: A Scoring Scale Used To Assess Student Performance Along A Task-Specific Set of CriteriaDocument4 pagesRubrics: Rubric: A Scoring Scale Used To Assess Student Performance Along A Task-Specific Set of CriteriaCathy OsielPas encore d'évaluation

- Performance-Based Assessment for 21st-Century SkillsD'EverandPerformance-Based Assessment for 21st-Century SkillsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (14)

- Module 4 Authentic AssessmentDocument7 pagesModule 4 Authentic Assessmentapi-249799367Pas encore d'évaluation

- Autumn2003 Rubrics MuellerDocument36 pagesAutumn2003 Rubrics MuellerSylvaen WswPas encore d'évaluation

- Types of RubricsDocument7 pagesTypes of RubricsGianellie BantugPas encore d'évaluation

- Rubric Assignment Fixedv2Document13 pagesRubric Assignment Fixedv2api-250420087Pas encore d'évaluation

- Using Rubrics for Performance-Based Assessment: A Practical Guide to Evaluating Student WorkD'EverandUsing Rubrics for Performance-Based Assessment: A Practical Guide to Evaluating Student WorkÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (2)

- Process-Oriented Performance Based AssessmentDocument22 pagesProcess-Oriented Performance Based Assessmentmichargonillo97% (35)

- SS301 - Learning OutcomeDocument31 pagesSS301 - Learning OutcomeEVELYN GRACE TADEOPas encore d'évaluation

- Scoring RubricsDocument14 pagesScoring RubricsRay Chris Ranilop OngPas encore d'évaluation

- Analyzing Student Work: Feedback and ImprovementDocument35 pagesAnalyzing Student Work: Feedback and ImprovementSanjay Kang ChulPas encore d'évaluation

- Authentic Assessment Toolbox For Higher Ed FacultyDocument7 pagesAuthentic Assessment Toolbox For Higher Ed FacultyChevin CaratPas encore d'évaluation

- Authentic AssessmentDocument7 pagesAuthentic AssessmentSafaa Mohamed Abou KhozaimaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Measurement Assessmen NT and Evaluation in Outcomes Based EducationDocument5 pages2 Measurement Assessmen NT and Evaluation in Outcomes Based EducationVanessa DacumosPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is A RubricDocument3 pagesWhat Is A RubricAhmad Firdaus Zawawil AnwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Performance AssessmentDocument7 pagesPerformance AssessmentDee DiahPas encore d'évaluation

- What Are RubricsDocument6 pagesWhat Are RubricsNanette A. Marañon-SansanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 2Document10 pagesChapter 2Jack FrostPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 1. What Is Performance-Based Learning and Assessment, and Why Is It Important?Document6 pagesChapter 1. What Is Performance-Based Learning and Assessment, and Why Is It Important?Thea Margareth MartinezPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessing Student WritingDocument29 pagesAssessing Student WritingPrecy M AgatonPas encore d'évaluation

- Important Characteristics of RubricsDocument4 pagesImportant Characteristics of RubricsNimsaj PioneloPas encore d'évaluation

- Important Characteristics of RubricsDocument4 pagesImportant Characteristics of RubricsNimsaj PioneloPas encore d'évaluation

- Glossary-Of-Terms JEREMIAH BABAODocument5 pagesGlossary-Of-Terms JEREMIAH BABAOJeremiahPas encore d'évaluation

- VOL1 No 1 MuellerDocument8 pagesVOL1 No 1 MuellerAn Phu Plaza SalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Analytic Versus Holistic RubricsDocument13 pagesAnalytic Versus Holistic RubricsminaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 2Document24 pagesUnit 2Fahad Shah JehanPas encore d'évaluation

- Holistic ChecklistDocument1 pageHolistic ChecklistEka Gt AjoesPas encore d'évaluation

- Handout Module 2Document8 pagesHandout Module 2NurmainnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Criterion Ref Assessment PDFDocument17 pagesCriterion Ref Assessment PDFlaukingsPas encore d'évaluation

- The Aligned CurriculumDocument14 pagesThe Aligned CurriculumMuhammad Ramdhan PurnamaPas encore d'évaluation

- SPED 9 MIDTERM 1st Sem 2021 22.angeline P. OrdeÑizaDocument3 pagesSPED 9 MIDTERM 1st Sem 2021 22.angeline P. OrdeÑizarenato jr baylasPas encore d'évaluation

- Developing Scoring RubricsDocument4 pagesDeveloping Scoring Rubricsanalyn anamPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Authentic AssessmentDocument5 pagesWhat Is Authentic AssessmentBrian Brangzkie TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 9 AssessmentDocument6 pagesModule 9 AssessmentAcsaran Obinay21Pas encore d'évaluation

- Question No. 2: Instructional ObjectivesDocument4 pagesQuestion No. 2: Instructional ObjectivesMuhammad Hammad RashidPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment Strategies and ToolsDocument37 pagesAssessment Strategies and Toolscelso eleptico100% (1)

- Basic Concepts and Principles in Assessing Learning: Lesson 1Document9 pagesBasic Concepts and Principles in Assessing Learning: Lesson 1Jasper Diñoso JacosalemPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment in MathematicsDocument53 pagesAssessment in MathematicsNelia GrafePas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment in Learning 1Document5 pagesAssessment in Learning 1tristanjerseyfernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture Notes On The Nature of AssessmentDocument17 pagesLecture Notes On The Nature of AssessmentGeorge OpokuPas encore d'évaluation

- Assess 2 Module 2Document10 pagesAssess 2 Module 2jezreel arancesPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 For Competency Based Assessment 1Document10 pagesModule 2 For Competency Based Assessment 1jezreel arancesPas encore d'évaluation

- 3Document7 pages3Cathlyn MerinoPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment at Havergal 1Document4 pagesAssessment at Havergal 1Lora YuPas encore d'évaluation

- Grading RubricsDocument7 pagesGrading RubricskondratiukdariiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Defining Curriculum Objective and Intended Learning OutcomesDocument9 pagesDefining Curriculum Objective and Intended Learning OutcomesKrizzle Jane PaguelPas encore d'évaluation

- MAJ 20 Input and Output 5Document6 pagesMAJ 20 Input and Output 5majedz 24Pas encore d'évaluation

- Scoring Rubrics: What, When and How?: Barbara M. MoskalDocument6 pagesScoring Rubrics: What, When and How?: Barbara M. MoskalYasmine MoghrabiPas encore d'évaluation

- PCK 6 Assessment of Learning 2 Unit 2Document21 pagesPCK 6 Assessment of Learning 2 Unit 2Maricel RiveraPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1 INTRODUCTION TO ASSESSMENT IN LEARNING PEC 8Document6 pagesLesson 1 INTRODUCTION TO ASSESSMENT IN LEARNING PEC 8Erick JohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment Procedure Relating Instructional ObjectivesDocument34 pagesAssessment Procedure Relating Instructional ObjectivesMalik MusnefPas encore d'évaluation

- Checklists, Rating Scales and Rubrics (Assessment)Document3 pagesChecklists, Rating Scales and Rubrics (Assessment)NUR AFIFAH BINTI JAMALUDIN STUDENTPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is A RubricDocument2 pagesWhat Is A Rubricjasmina2869Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Assessment in Learning: Lesson 1: Basic Concepts and Principles in Assessing LearningDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Assessment in Learning: Lesson 1: Basic Concepts and Principles in Assessing LearningRonie DacubaPas encore d'évaluation

- Alternative Names For Authentic AssessmentDocument4 pagesAlternative Names For Authentic AssessmentWiljohn de la CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- Short SummaryDocument15 pagesShort SummaryJamina JamalodingPas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment Terminology: A Glossary of Useful Terms: AccountabilityDocument8 pagesAssessment Terminology: A Glossary of Useful Terms: AccountabilityLawson SohPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Performance-Based Education?Document11 pagesWhat Is Performance-Based Education?milca leonardoPas encore d'évaluation

- TeachignStrategies FINAL VERSIONDocument47 pagesTeachignStrategies FINAL VERSIONCarla Arce100% (1)

- Would You Rather... List of QuestionsDocument8 pagesWould You Rather... List of QuestionsCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- TeachignStrategies FINAL VERSIONDocument47 pagesTeachignStrategies FINAL VERSIONCarla Arce100% (1)

- Sparrows, Robins, and YouDocument1 pageSparrows, Robins, and YouCarla Arce100% (1)

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument4 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- Would You Rather... List of QuestionsDocument8 pagesWould You Rather... List of QuestionsCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- Precolonial Literature of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesPrecolonial Literature of The PhilippinesCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- SHS Core - Oral Communication CGDocument7 pagesSHS Core - Oral Communication CGEstela Benegildo67% (3)

- ADAPTATION - The Boy Who Listened To The SeaDocument1 pageADAPTATION - The Boy Who Listened To The SeaCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- Eveline: James JoyceDocument2 pagesEveline: James JoyceCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- A Kettle of Hawks-UneditedDocument1 pageA Kettle of Hawks-UneditedCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- PSSLC in MathematicsDocument53 pagesPSSLC in MathematicsRhoda Dela CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- A Kettle of Hawks-UneditedDocument1 pageA Kettle of Hawks-UneditedCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- Methodology and Descriptive ResearchDocument14 pagesMethodology and Descriptive ResearchCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- Active Volcano Found Under Antarctic IceDocument2 pagesActive Volcano Found Under Antarctic IceCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- Eldorado: Edgar Allan PoeDocument1 pageEldorado: Edgar Allan PoeCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- Chaucer's Tales AnalysisDocument13 pagesChaucer's Tales AnalysisCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- The Professionalization of TeachingDocument1 pageThe Professionalization of TeachingCarla ArcePas encore d'évaluation

- Process-Oriented Performance-Based Assessment Part 1Document44 pagesProcess-Oriented Performance-Based Assessment Part 1Carla Arce100% (1)

- Worksheet Purcom FinalDocument57 pagesWorksheet Purcom FinalMa.Luzmin CadalinPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson Plan Eyl Home N FamilyDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Eyl Home N FamilySunardi AhmadPas encore d'évaluation

- International Handbook of Emotions in Education: Educational Psychology in PracticeDocument4 pagesInternational Handbook of Emotions in Education: Educational Psychology in PracticeSusana JaramilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Inovasi PosterDocument1 pageInovasi PosterLookAtTheMan 2002Pas encore d'évaluation

- Activity Sheet Q1W2 All SubjectDocument27 pagesActivity Sheet Q1W2 All SubjectAiza Conchada100% (1)

- Up00102 French Languange Level 1Document8 pagesUp00102 French Languange Level 1Sh ShaezaPas encore d'évaluation

- Smart+Planet+1 LessonProgramme LOMCE 2015 EngDocument281 pagesSmart+Planet+1 LessonProgramme LOMCE 2015 Engperis1404Pas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment Task 1: Written Questions: BSB50420Diploma of Leadership and ManagementDocument5 pagesAssessment Task 1: Written Questions: BSB50420Diploma of Leadership and Managementkarma Sherpa100% (1)

- Parker Beck ch11Document20 pagesParker Beck ch11api-365463992100% (1)

- Competency Appraisal 1Document13 pagesCompetency Appraisal 1Catherine AteradoPas encore d'évaluation

- TLESBasic Research Marungko and FullerDocument26 pagesTLESBasic Research Marungko and FullerMarianer MarcosPas encore d'évaluation

- CommunicationDocument1 pageCommunicationapi-352507025Pas encore d'évaluation

- RPMS - Grade 5 - VIERNES, RHODADocument66 pagesRPMS - Grade 5 - VIERNES, RHODARhoda ViernesPas encore d'évaluation

- Micro Teaching Is A Best Example For SimulationDocument2 pagesMicro Teaching Is A Best Example For SimulationdelnaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pre - School Teacher Trainer Handbook: EnglishDocument44 pagesPre - School Teacher Trainer Handbook: EnglishAkshara Foundation100% (3)

- DLL - OBSERVATION OR INFERENCE SEPT 1-5 J 2022 FinalDocument5 pagesDLL - OBSERVATION OR INFERENCE SEPT 1-5 J 2022 FinalLhynn HiramiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Machine Learning: BITS PilaniDocument61 pagesMachine Learning: BITS PilaniSimran sandhuPas encore d'évaluation

- Grade 7 ENG LAS MELC 1 Week 1. QTR 2Document5 pagesGrade 7 ENG LAS MELC 1 Week 1. QTR 2Stvn RvloPas encore d'évaluation

- Gala National High School: Classroom Observation PlanDocument6 pagesGala National High School: Classroom Observation PlanRizia RagmacPas encore d'évaluation

- Daily Lesson Plan StoriesDocument8 pagesDaily Lesson Plan Storiesina_oownPas encore d'évaluation

- Educ 3be TTL2 Module 1.1Document5 pagesEduc 3be TTL2 Module 1.1Gretel T RicaldePas encore d'évaluation

- How To Answer Directed WritingDocument12 pagesHow To Answer Directed WritingAwin SeidiPas encore d'évaluation

- FED 242 AssignmentDocument2 pagesFED 242 AssignmentAdebisi jethroPas encore d'évaluation

- Tefl Teaching VocabDocument5 pagesTefl Teaching Vocabnurul vitaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Sultana AkterDocument2 pagesSultana AkterMd Aríf Hussaín AlamínPas encore d'évaluation

- 1st Grading g9 Eating Habits July 30 Aug3Document6 pages1st Grading g9 Eating Habits July 30 Aug3Gene Edrick CastroPas encore d'évaluation

- SHS Core - PE and Health CG - 0 PDFDocument12 pagesSHS Core - PE and Health CG - 0 PDFjrbajao100% (1)

- REVIEWERDocument137 pagesREVIEWERJulius Caesar PanganibanPas encore d'évaluation

- ENHANCING STUDENTS Problem Solving SkillsdocxDocument6 pagesENHANCING STUDENTS Problem Solving SkillsdocxBab SitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Education CatalogDocument80 pagesEducation CatalogJoy SimanjuntakPas encore d'évaluation