Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

A New Approach To Athletics Competition and Training For Children in Australia

Transféré par

Jörg ProbstDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A New Approach To Athletics Competition and Training For Children in Australia

Transféré par

Jörg ProbstDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

A new approach to athletics competition and training for children in Australia

Jrg Probst 1

This paper argues for a complete overhaul of the athletics competition and training system for children in the interest of a more effective long term development of our athletes and our sport as a whole.

We know a lot about the long-term development of athletes. That knowledge has been around for over two decades at least. Most of us would agree on these principles: Children are not little adults and therefore must not train like adults; Children should have fun whilst learning fundamental movement skills; Early specialisation in training and competition endangers or shortens athletes careers there is plenty of literature and more than enough anecdotal evidence on this, key word: burnout (physical and/or mental); Training and competition must have a motivating effect and have a positive effect on the athletes health; Training and competition must take into account the childrens biological and chronological age it is common sense, children mature at different rates; Developing basic and general movement and coordination skills early on are an indispensable precondition for the development of talent later on. These basic skills facilitate the future acquisition of more specialised and complex skills.

We know all this and much more, and weve known it for a long time. And yet, children doing athletics in this country are exposed to a competition system which is essentially the same as that of youth, junior and senior athletes, both through the school system and through Little Athletics, with some fairly minor modifications. And despite the laudable Little Athletics motto of fun, family, fitness, the reality is that competition is often very serious business, for parents, coaches, clubs and centres and schools perhaps even more so than for the young athletes themselves. Coaches, age managers, parents, even though they might know better, are naturally coaching children in a way that would be more appropriate for adolescents or even adults, simply because the competition system demands it. Coaches are teaching to the competition the same way school teachers teach to academic tests such as the NAPLAN or the HSC. In neither scenario is the learning experience and outcome optimal.

1

Declaration: I am a director of Athletics New South Wales Limited (ANSW), a member of the ANSW Competition Advisory Panel, a coach and an athlete. The opinions expressed in this paper are entirely my own.

In short, the current situation makes true long-term athlete development virtually impossible. Over 20 years ago, in what was then still known as West Germany, Friedrich & Holz (1989) made the point that all scientific advances about a systematic long-term build-up of athletes remain academic as long as federations do not implement this knowledge in their competition systems. After all, the competition system determines the goals, the content, the methods and setup of the training system not the other way round. A specialised competition system for children and youths results in a specialised training systems in those age groups. [] Specific competition demands lead to specific demands in training. [] [My translation] Only a few months earlier, on the other side of the wall dividing the two Germanys, Borde & Becker (1989) had recognised the exact same problems and raised the same issue. If training for youngsters was to become more effective, they reasoned, the competition system would have to reflect the training strategies. This is clearly not a chicken and egg question. But what is the alternative? Well, it is really quite simple: the general and basic movement skills that children should learn and practise in training should be reflected in the competition system. It follows as a logical conclusion that our competition system for children must be radically changed! Friedrich & Holz (1989) put it like this: The contents of the basic and build-up training stages must also be fundamental ingredients of the competition system in the respective age groups [] The official competition program of the respective age groups must be harmonised with the training content. [My translation] We know that nothing of the sort happened in post-Wall Germany either, at least not until recently. But not only Germany is now taking measures to overhaul its competition system for children, with largely positive reactions. Switzerland too has implemented special competition programs for children (Probst, 2012). Other countries are likely to follow. The following quote is from Athletics Canadas introduction to a document entitled Long Term Athlete Development: Children who do not develop their fundamental motor skills by age 12 are unlikely to reach their genetic athletic potential. [] Establishing a core set of motor skills early in life enables children to gain a sense of achievement and establish a positive relationship with sport and physical activities. And the Canadians have acknowledged: The current system for Canadian athlete development emphasizes winning and competing, instead of maximizing the windows of accelerated adaptation to training and developing fundamental sport skills. The current emphasis on outcome (winning) as opposed to process (skill development) is seen as a shortcoming in the Canadian sport system. Such practices 2

may lead to one-sided preparation, early burnout, lost potential or over-training as noted through the practices identified by the Canadian Sport Centres LTAD Expert Group. It seems the Canadians are or were sitting in the same boat as us. I dont know what they have actually done about the situation. Ten years ago, a very detailed academic study of athlete identification and development in the UK (Wolstonecraft, 2002) named mini-sports as one of the stumbling blocks for long term athlete development. These mini-sports teach children a series of specialised skills, rather than focus on more generalised and a wider variety of skills and thereby do not help athletes gain a broad range of movement experiences (p. 21). A more recent example in Australia is the introduction of mini-tennis. A very long-standing example is Little Athletics. The IAAF has recognised the need for change, which is why the IAAF Kids Athletics program was developed. The introduction to the IAAF Kids Athletics manual says: After numerous research initiatives, discussion panels and pilot events it has become apparent that there is an urgent need to develop a new type of program for children. Where is the urgency in Australia to change things for the better? The IAAF Kids Athletics program is only a starting point in my view. There are many ways children can be even better engaged with athletics. I find the approach taken in Germany and Switzerland more appealing than the IAAF program, but I believe we should come up with our own training framework and competition program suitable for children, which suit our particular circumstances and context. There is no reason why enjoyable team-based activities cant be used for competition purposes. These activities dont have to be standardised across the country. Clubs, Little Athletics centres and schools should be able to choose from a large catalogue of kids athletics events, many of which would be quite suitable for team based competition where there is no pressing need for a stop watch or a measuring tape, and only minimal equipment is required. This would also vastly increase the accessibility of athletics as a sport. In fact, with a bit of imagination every coach can use their particular facilities and available equipment to produce a smorgasbord of fun, challenging, and competitive relay exercises for children. Variety is an important ingredient in keeping children interested. At this point it is worth mentioning that some exemplary general skills development initiatives are already on foot at Little Athletics NSW. However, as long as the current Little Athletics competition system is in place, nothing will change on a broader scale. We will continue to experience huge dropout rates, and our most talented athletes long term development continues to be compromised. Official figures are not available, but around 50% of the 100,000 or so children who sign up for Little Athletics will not return the following year. Presumably no statistics would be available on how 3

many children drop out very early in the season either, but going by my own observations the early dropout rates are quite high. To be clear, although I am of the opinion that in the long run this country, like every other country in the world, should have one athletics movement rather than two, I am advocating here an overhaul of the way athletics is delivered to children, both in schools and in Little Athletics, both in terms of training and competition. This is about how children experience our sport, and how they can best benefit from being involved. Its about improving one of our most important products, namely competition, whilst at the same time preparing the participants for continuing involvement in our sport, either as recreational or elite athletes. The Little Athletics movement, including the many centres and the governing bodies, and of course the schools, have a key role to play in delivering a better, more child-appropriate competition and training system. We need a competition system that fosters the development of the more basic but also more complex general motor skills, often referred to as physical literacy. This way we will build the foundations for future success for those who have the necessary ambition whether in athletics, or in another sport, but we also cater for those who simply want to have fun and enjoy sport and stay fit. Granted, nothing less than a paradigm shift is required to achieve this! Many parents and even some coaches may be upset that little Johnny is no longer able to be a champion shot putter or discus thrower at age 7, but we mustnt let these sorts of misplaced ambitions guide us. Its not about the parents and the coaches. Whatever we do should be in the interest of the athletes. I am convinced that the vast majority of parents would come to appreciate very quickly not only the fact that their children learn more skills, but are more active during their training and competition, and enjoy their athletics experience more. Also, those parents who are actively involved in Little Athletics would no doubt enjoy their roles much more. The centres would find that more kids are staying involved for longer, and fewer children would drop out, with a likely flow-on effect on retention of officials and other volunteers. School teachers might find that more students participate willingly and perhaps even with enthusiasm. A new, child-appropriate competition (and therefore training) system would also form a solid basis for any meaningful talent identification and development program, and ultimately this would result in more sustained and more successful high performance careers. Little Johnny would probably have a better chance of actually becoming a champion when it really matters from age 18 onwards - because he has learnt the basic skills early, can later on learn the complex skills of shot putting and discus throwing more easily and correctly, and - provided general training remains part of his training regimen throughout childhood and adolescence - his body is better prepared for undertaking the kind of training that is required to become a champion shot putter or discus thrower.

Recently our coach education system has undergone some drastic changes. Under the auspices of Athletics Australia the new coaching courses targeted at coaches working with children now require coaches to build the basic movements skills in children. The only problem is that this is never going to have the intended effect unless the competition system for children is changed, which underlines the need for coordinated change. So how can we bring about the required change, this paradigm shift? We certainly dont need to reinvent the wheel. But we need all our governing bodies, clubs and coaches to take note and work on this together. However, appeasement will not get us anywhere. Agreeing to disagree will not do. What we need is open and frank debate amongst all stakeholders, followed up by swift, decisive action. Above all, we need people who are prepared to slaughter some sacred cows, people who have vision, who have the courage and the will to take the lead and make this paradigm shift happen - in the interest of our athletes and our wonderful sport of athletics.

Bibliography

Athletics Canada. (n.d.). Long term athlete development. Borde, A., & Becker, M. (1989). Grundpositionen zur bereinstimmung von Trainings-und Wettkampfinhalten im Nachwuchsleistungssport. Training und Praxis des Leistungssports, 158-164. Friedrich, E., & Holz, P. (1989). Ein Konzept zur Talentfrderung im bundesdeutschen Leistungssport. Leistungssport, 19(4), 5-10. Kupper, K., & Thiess, G. (1971). Die Schaffung wirksamer Auswahlsysteme fr den Leistungssport in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik. Theorie und Praxis des Leistungssports, 9(1/2), 1850. Metzig, F.-M., & Knzel, R. (1968). Erfahrungen bei der weiteren Vervollkommnung des Systems der Sichtung und Auswahl. Training und Praxis des Leistungssports, 31, 240-248. Probst, J. (2012). Talent identification and selection in Switzerland. unpublished. Wolstonecroft, E. (2002). Talent identification and development: an academic review. Edinburgh: Sportsctoland.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

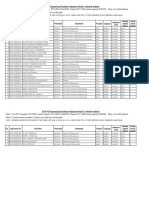

- Analysis First Three Generations of Australian WYC ParticipantsDocument7 pagesAnalysis First Three Generations of Australian WYC ParticipantsJörg ProbstPas encore d'évaluation

- Modern Athletics 1875Document14 pagesModern Athletics 1875Jörg ProbstPas encore d'évaluation

- Court of Arbitration For Sport Decision Re 2000 US Relay TeamsDocument6 pagesCourt of Arbitration For Sport Decision Re 2000 US Relay TeamsJörg ProbstPas encore d'évaluation

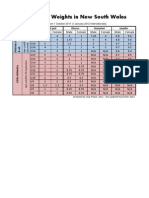

- Implement Weights NSWDocument1 pageImplement Weights NSWJörg ProbstPas encore d'évaluation

- Probst-Developing Athletes and AthleticsDocument3 pagesProbst-Developing Athletes and AthleticsJörg ProbstPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Second Language Acquisition EssayDocument7 pagesSecond Language Acquisition EssayManuela MihelićPas encore d'évaluation

- Declaration On Schools As Safe SanctuariesDocument3 pagesDeclaration On Schools As Safe SanctuariesFred MednickPas encore d'évaluation

- Duties of Nursing PersonnelDocument34 pagesDuties of Nursing PersonnelEzzat Abbariki85% (13)

- Final Project SyllabusDocument4 pagesFinal Project Syllabusapi-709206191Pas encore d'évaluation

- English 10 First Quarter Week 6Document4 pagesEnglish 10 First Quarter Week 6Vince Rayos Cailing100% (1)

- Values Education - WikipediaDocument3 pagesValues Education - Wikipediaindhu mathiPas encore d'évaluation

- Armine Babayan EDUC 5810 Unit 2 Written AssignmentDocument3 pagesArmine Babayan EDUC 5810 Unit 2 Written Assignmentpeaceambassadors47Pas encore d'évaluation

- EnglDocument64 pagesEnglBene RojaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maths - CHANCE & PROBABILITY Unit Plan Year 5/6Document20 pagesMaths - CHANCE & PROBABILITY Unit Plan Year 5/6mbed201050% (4)

- Career Objective:: Kolipakula SuneeldattaDocument4 pagesCareer Objective:: Kolipakula SuneeldattaNathaniel Holt0% (1)

- PDP Lesson Plan Template: Group Member: Patricia Guevara de HernándezDocument2 pagesPDP Lesson Plan Template: Group Member: Patricia Guevara de HernándezPatricia Guevara de HernandezPas encore d'évaluation

- SopDocument5 pagesSopMayur JagtapPas encore d'évaluation

- Problem-Solving Techniques in MathematicsDocument24 pagesProblem-Solving Techniques in MathematicsNakanjala PetrusPas encore d'évaluation

- Back To School Night InfoDocument3 pagesBack To School Night Infoapi-325512473Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Very Hungry Caterpillar Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesThe Very Hungry Caterpillar Lesson Planapi-291353197Pas encore d'évaluation

- An Online Course in A NutshellDocument7 pagesAn Online Course in A Nutshellapi-3860347Pas encore d'évaluation

- Goal Statement Walden University PDFDocument2 pagesGoal Statement Walden University PDFVenus Makhaukani100% (1)

- A-My Little BrotherDocument6 pagesA-My Little BrotherOliver ChitanakaPas encore d'évaluation

- 171934210Document4 pages171934210Henry LimantonoPas encore d'évaluation

- Sas11 SPX007Document5 pagesSas11 SPX007Reygen TauthoPas encore d'évaluation

- CSIT111 SubjectOutline Feb2018Document11 pagesCSIT111 SubjectOutline Feb2018kentwoonPas encore d'évaluation

- 1) Lesson 5. Teaching As Your Vocation, Mission and ProfessionDocument9 pages1) Lesson 5. Teaching As Your Vocation, Mission and ProfessionMichelle Calongcagon-Morgado86% (14)

- Teflfullcircle LessonPlanDocument5 pagesTeflfullcircle LessonPlanShayene Soares27% (11)

- Sociology of EducationDocument35 pagesSociology of EducationAchidri JamalPas encore d'évaluation

- Bonifacio LawDocument5 pagesBonifacio LawDanae CaballeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Education English SpeechDocument1 pageEducation English SpeechDhohan Firdaus Chania GollaPas encore d'évaluation

- Coursera WQZW5M975YDBDocument1 pageCoursera WQZW5M975YDBSelena DemarchiPas encore d'évaluation

- Kellogg's Career Development CaseDocument2 pagesKellogg's Career Development CaseSnigdhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Gcse D&T TextileDocument29 pagesGcse D&T TextileOlusaye OluPas encore d'évaluation

- Microteaching - 2.4.18 (Dr. Ram Shankar)Document25 pagesMicroteaching - 2.4.18 (Dr. Ram Shankar)ramPas encore d'évaluation