Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Excerpt: "How To Be Secular" by Jacques Berlinerblau

Transféré par

wamu885Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Excerpt: "How To Be Secular" by Jacques Berlinerblau

Transféré par

wamu885Droits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

4

Does Secularism Equal Atheism?

Secularism leaves the mystery of deity to the chartered imagi-

nation of man, and does not attempt to close the door of the fu-

ture, but holds that the desert of another existence belongs only

to those who engage in the service of man in this life.

—George Jacob Holyoake, English Secularism

American secul arism has lost control of its identity and image.

That’s because the equation secularism = atheism is rapidly gaining

market share. It is increasingly employed in popular usage, political

analysis, and even scholarly discourse. This formula is muscling out

an infinitely more accurate understanding of secularism as a political

philosophy about how the state should relate to organized religion.1

If this association prevails, if secularism simply becomes a synonym

for atheism, then secularism in the United States will go out of busi-

ness.

Which is fine by the Revivalists and which may account for why

they perpetuate this confusion. In these circles secularism has be-

come another word for godlessness. As one journalist perceptively

observes, “secular” is a “code in conservative Christian circles for

‘atheist’ or even ‘God-hating’ . . . conjur[ing], in a fresh way, all the

demons Christian conservatives have been fighting for more than 30

years: liberalism, sexual permissiveness, and moral lassitude.”2

Not only foes draw this link, but friends as well. The website of the

Secular Coalition for America describes the group as “a 501(c)4 advo-

cacy organization whose purpose is to amplify the diverse and grow-

ing voice of the nontheistic community in the United States.”3 This

Berlinerblau_SECULAR_int_F.indd 53 6/19/12 3:32 PM

54 What Secularism Is and Isn’t

community, it points out, is comprised of “atheists, agnostics, human-

ists, freethinkers, and other nontheistic Americans.”4 An affiliated or-

ganization, the Secular Student Alliance, refers to its mission as “to

organize and empower nonreligious students around the country.”5

Why must so-called secular organizations be focused exclusively

on nonbelievers? After all, just a few decades back, in secularism’s

mild separationist golden age, all sorts of religious believers could

have been categorized as secularists. The term could refer to a Bap-

tist, a Jew, a progressive Catholic, a Unitarian, and so on. Also, there

were secular identities that didn’t make any reference to a person’s

religious belief or lack thereof. A secularist might just as likely have

been a public school teacher, a journalist, a civil rights activist, a pro-

fessor, a Hollywood mogul, a civil libertarian, a pornographer, and so

forth. From the 1940s to the 1980s all of the aforementioned groups

mobilized on behalf of secular causes, the most prominent being sep-

aration of church and state.

Aside from being preposterously imprecise, the equation secu-

larism = atheism gravely undermines the potential of secularism as

a political movement. It leaves people of faith with little incentive

to buy in and reduces secularism’s personnel to the size of the tiny

American atheist movement.6

This equation poses a serious public relations problem as well.

The atheist movement is not just small, but it is also among the least

popular groups in the United States.7 A survey in 2007 found that re-

spondents viewed nonbelievers more unfavorably than any other co-

hort they were asked about. This included Muslims, whom the athe-

ists somehow edged out by eighteen percentage points.8 If atheists

are perceived to “own” secularism, its approval ratings will plummet

even further.

This is certainly not the fault of atheists, the vast majority of whom

are tolerant, self-critical, and moderate in their outlook (that is, sec-

ularish). And were a true secular movement to be forged, it should

make the eradication of anti-atheist prejudice integral to its plat-

form. The fact remains, however, that the more secularism becomes

narrowly equated with atheism, the less it will be able to forge coali-

tions and pursue its agenda effectively.

Which brings us, then, to the aforementioned impending bank-

Berlinerblau_SECULAR_int_F.indd 54 6/19/12 3:32 PM

Does Secularism Equal Atheism? 55

ruptcy. The growing popularity of the secularism = atheism equa-

tion has to do with the advent of a group known as the New Athe-

ists. Incensed by the political and cultural might of the Revivalists,

this movement crashed into the public square in 2004.9 The result

included enviable book sales, preposterous polemics, and the almost

overnight development of a national media platform.10

Yet instead of honing their powers of critique on anti-secular Re-

vivalists, the New Atheists advanced a mixed-martial-arts assault on

religion in general. They gleefully (and catastrophically) set about

pitting nonbelievers against all believers. They thus included in their

onslaught the one constituency in whose hands the future of secular-

ism lies: religious moderates. The New Atheist creed maintains that

moderates are just as dangerous and misguided as their extremist co-

religionists.

Here is Sam Harris, offering his characteristically subtle take on

the question: “Religious moderates are, in large part, responsible

for the religious conflicts in our world, because their beliefs provide

the context in which scriptural literalism and religious violence can

never be adequately opposed.”11 Richard Dawkins, in The God Delu-

sion, includes a self-explanatory section titled “How ‘Moderation’

in Faith Fosters Fanaticism.” “Even mild and moderate religion,” he

avers, “helps to provide the climate of faith in which extremism nat-

urally flourishes.”12 Surely a school of thought that can’t distinguish

between a member of the Taliban beheading a journalist and a Meth-

odist running a soup kitchen in Cincinnati is not poised to make the

sound policy decisions that accrue to the good of secularism.

The precise relation of atheism to secularism needs to be teased

out and explained to the general public. This is actually an old di-

lemma, one that was debated a century and a half ago. There, the

possibility was raised that the passions of extreme atheism tend to

muck up the agenda of secularism.

Secularism Born Again?

Opinions differ as to when secularism was born. One approach fo-

cuses on Christian premodernity and identifies Paul and Augustine

Berlinerblau_SECULAR_int_F.indd 55 6/19/12 3:32 PM

56 What Secularism Is and Isn’t

as having laid down the initial tracks of the secular vision. The sec-

ond, which is preferable, points to the high-speed thought corridor

that stretched from the Reformation to the Enlightenment. It was

there, in early modernity, that the Luther-Locke-Jefferson line car-

ried the secular vision into the sunlight of Reason.

Others, however, identify a completely different starting point: the

winter of 1851, when the Englishman George Jacob Holyoake (1817–

1906) recalls having coined the word secularism (his contribution

being the suffixing of that -ism onto the word secular). He shared

that recollection in a book written forty-five years later, so, unless his

memory was flawless, perhaps we should not canonize the precise

date.13 Suffice it to say that secularism experienced a third and auspi-

cious birth sometime during the mid-nineteenth century.

For some it is Holyoake, not Jefferson, nor Locke, nor Luther, who

is the true father of secularism. And if secularism suffers from a def-

initional crisis today, let us note in passing that to him must be as-

cribed some responsibility for that as well. In his works, such as The

Principles of Secularism of 1871, he somehow managed to define sec-

ularism in about a dozen different ways.14

This complex figure lived a long and tumultuous life in what must

have been a very interesting era to think outside the confines of Chris-

tianity. The viselike grip of ecclesiastical control was clearly loosen-

ing in Victorian England. This context provided a perfect, though not

necessarily risk-free, environment for Holyoake and countless other

“infidels” to mount a ferocious attack on the status quo.

In his youth, Holyoake was a relentless critic of Christianity. Like

so many Victorian dissenters, he spent time in jail for blasphem-

ing.15 In 1843 he bitterly, but eloquently, recounted the tale of his im-

prisonment in his essay “A Short and Easy Method with the Saints.”

There, the twenty-five-year-old protests that “religion is ever found

the mother of mental prostration, and the right arm of political op-

pression.”16

Holyoake was understandably enraged at having been thrown in

a dungeon for an off-the-cuff poke at Christianity he had made while

taking questions after a lecture. He complained that this religion

forces the concession of “man’s noblest right, the right of expressing

his opinions.”17 “Infidels have never received anything from Chris-

Berlinerblau_SECULAR_int_F.indd 56 6/19/12 3:32 PM

Does Secularism Equal Atheism? 57

tians,” he broods, “but calumny, contempt, insult, imprisonment, and

death.”18

As he aged, however, Holyoake’s views would mellow and evolve

in ways that make him difficult to categorize. In his early life he threw

his lot in with atheism, but one scholar sees him drifting to agnosti-

cism in his old age.19 Another writer refers to him as a “lukewarm”

atheist and notes that Holyoake “was sympathetic to religion.”20 He

saw secularism as a worldview or system of ethics that moved to-

ward knowledge of God insofar as it assiduously strived to discover

the truth.21 Holyoake, for his part, endorsed an “atheism of reflec-

tion,” which “listens reverentially for the voice of God, which weighs

carefully the teachings of a thoughtful Theism; but refuses to recog-

nize the officious, incoherent babblement of intolerant or presump-

tuous men.”22

This calls attention to a very important truth about self-professed

atheists in the nineteenth century and most likely today as well:

rather than having a fixed lifelong identity as deniers of God’s exis-

tence, there is a recurrent fluctuation in their thought.23 Individual

atheists change across the course of a lifetime.

Should this be surprising? People change. Theists change. Athe-

ists change. The latter are not godless every minute of their lives. Nor

are the former lacking in doubts. Extreme theists and extreme athe-

ists insist on locking people into one fixed identity. But atheist iden-

tity is always in flux.24 How to be secular? In matters metaphysical,

keep an open mind or, as we shall see later, “don’t get overwrought.”

In any case, Holyoake refined and defended his thought about

secularism across more than a half-century of published work. His

initial comment from 1851, referenced earlier, maintained that “sec-

ular” connoted “principles of conduct, apart from spiritual consid-

erations.”25 Gaining attention and growing in stature, the rising star

would publish a book a few years later called Principles of Secular-

ism.26 There he offered up a plethora of definitions. It is hard to pin-

point which understanding of his subject he preferred, but the fol-

lowing would seem to represent his view well: “Secularism is the

study of promoting human welfare by material means; measuring

human welfare by the utilitarian rule, and making the service of oth-

ers a duty of life. Secularism relates to the present existence of man

Berlinerblau_SECULAR_int_F.indd 57 6/19/12 3:32 PM

58 What Secularism Is and Isn’t

. . . [it is] a series of principles intended for the guidance of those who

find Theology indefinite, or inadequate, or deem it unreliable.”27

Holyoake’s sympathetic readers were variously confused, elated,

or angered by this definition. Let’s begin with confusion: a passenger

on the Luther-Locke-Jefferson line might be justifiably flummoxed.

Where is the reference to order? the state? the church? In truth, po-

litical conceptions of secularism were always an afterthought for

Holyoake. He did occasionally contemplate the role of government,

as when he wrote, “The State should forbid no religion, impose no re-

ligion, teach no religion, pay no religion.”28

Ethicists, however, might be elated by a definition that placed

the accent of secularism on moral behavior instead of politics. Holy-

oake, as we have seen, spoke of principles that were to guide secular-

ists, what he called “a code of duty pertaining to this life.”29 Foremost

among them were the following mantra-like propositions: (1) “the

improvement of this life by material means,” (2) “science is the avail-

able Providence of man,” and (3) “it is good to do good.”30

Holyoake’s definition(s) not only stressed ethics, but ethics geared

to the present. “Secularity,” he commented, “draws the line of sepa-

ration between the things of time and the things of eternity. That is

Secular which pertains to this world.”31 The emphasis on ethical ac-

tion in the here and now is constant through all of Holyoake’s think-

ing. Holyoake went so far as to opine, “Giving an account of ourselves

in the whole extent of opinion . . . we should use the word ‘Secularist’

as best indicating that province of human duty which belongs to this

life.”32

Thus far we have encountered two species of definitions of sec-

ularism: the political and the ethical. The political was born of the

Reformation and the Enlightenment. It stresses the relation between

religious institutions and government. Its bearers were our five vi-

sionary architects. The ethical definition was engendered by Holy-

oake and later on we will note its affinities with the thought of Saint

Augustine. We would add, parenthetically, that Holyoake’s approach

has lived a long and healthy life in dictionaries and encyclopedias in

the entry titled “Secularism.” Curiously, many reference books tend

to favor this ethical definition over the older political one that devel-

oped in Christian political philosophy.

Berlinerblau_SECULAR_int_F.indd 58 6/19/12 3:32 PM

Does Secularism Equal Atheism? 59

Among those who were chagrined by Holyoake’s approach would

be the small but growing band of Victorian infidels for whom he was

a hero and leader. True, Holyoake would earn their respect by cham-

pioning the cause of freedom of expression (a huge issue for an out-

spoken population that had a knack for getting thrown in the clink).33

But why didn’t his definition reference infidelity or atheism or agnos-

ticism or some such thing?

Holyoake intentionally omitted any reference to atheism in his

definition of secularism. To understand why is to glimpse a credible

alternative to the extreme forms of atheism that are coming to domi-

nate secularism today.

Charles Bradlaugh and the “War Against Religion”

George Jacob Holyoake had a younger, more charismatic, more in-

cendiary, more radical contemporary. A David to his Saul. A Malcolm

X to his Martin Luther King Jr.

His name was Charles Bradlaugh (1833–1891) and his biographer

describes him as a “proselytizing atheist” who would shout his un-

belief “from town halls and market squares.”34 Bradlaugh acquired

a well-earned reputation as one of the most angry, uncompromising

atheists in the world.35 He proudly referred to himself as one of the

“rough English skirmishers” in “the great Freethought army.”36 The

famed orator was the first president of the National Secular Society.

Founded in 1866, it was the flagship organization of Victorian infi-

delry.37

Like Holyoake, Bradlaugh had good reason for thinking ill of

Christianity. He too spent time in prison for articulating infidel

thoughts. Worse yet, Bradlaugh was literally thrown out of the very

parliament to which he had been democratically elected. This sad

saga, a sort of national scandal, was drawn out over six years, 1880–

1886. The controversy, which transfixed England, centered on how a

professed atheist could take a religious oath of office.38

In 1870 Bradlaugh and Holyoake held a storied two-night debate

in front of a boisterous audience of freethinkers. The relationship be-

tween the two men was not without its professional and personal an-

Berlinerblau_SECULAR_int_F.indd 59 6/19/12 3:32 PM

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Letter From D.C. Open Government Coalition On Secure DC BillDocument46 pagesLetter From D.C. Open Government Coalition On Secure DC Billwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Secure DC Omnibus Committee PrintDocument89 pagesSecure DC Omnibus Committee Printwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit in Support of Arrest of Larry GarrettDocument3 pagesAffidavit in Support of Arrest of Larry Garrettwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tridentis LawsuitDocument9 pagesTridentis Lawsuitwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- September 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting Minutes For ApprovalDocument3 pagesSeptember 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting Minutes For Approvalwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser Public Safety Bill, Spring 2023Document17 pagesD.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser Public Safety Bill, Spring 2023wamu885100% (1)

- Letter From Dean Barbara Bass Update On Residents and Fellows UnionizationDocument3 pagesLetter From Dean Barbara Bass Update On Residents and Fellows Unionizationwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Tridentis LawsuitDocument9 pagesTridentis Lawsuitwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lawsuit Against D.C. Over Medical Care at The D.C. JailDocument55 pagesLawsuit Against D.C. Over Medical Care at The D.C. Jailwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- WACIF AAC DevelopmentBoards 4.17Document4 pagesWACIF AAC DevelopmentBoards 4.17wamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Razjooyan CommentDocument1 pageRazjooyan Commentwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- NZCBI Reply To Holmes Norton Visitor Pass Inquiry - 2023 - 01 - 11Document1 pageNZCBI Reply To Holmes Norton Visitor Pass Inquiry - 2023 - 01 - 11wamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Captain Steve Andelman Lawsuit Against MPDDocument25 pagesCaptain Steve Andelman Lawsuit Against MPDwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- February 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting MinutesDocument5 pagesFebruary 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting Minuteswamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- September 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting Minutes For ApprovalDocument3 pagesSeptember 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting Minutes For Approvalwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- WAMU Community Council Meeting Minutes 09 2021Document6 pagesWAMU Community Council Meeting Minutes 09 2021wamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- February 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting MinutesDocument5 pagesFebruary 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting Minuteswamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2022-083 Designation of Special Event Areas - Something in The Water FestivalDocument3 pages2022-083 Designation of Special Event Areas - Something in The Water Festivalwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- WAMU Council Meeting Minutes 202112Document5 pagesWAMU Council Meeting Minutes 202112wamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Undelivered: The Never-Heard Speeches That Would Have Rewritten History ExcerptDocument11 pagesUndelivered: The Never-Heard Speeches That Would Have Rewritten History Excerptwamu8850% (1)

- Letter To Governor Hogan On Funding Abortion TrainingDocument3 pagesLetter To Governor Hogan On Funding Abortion Trainingwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Note: Kwame Makes This From Scratch, But You Can Find It at Most Grocery Stores or Online. Kwame's Recipe Is Included in The CookbookDocument3 pagesNote: Kwame Makes This From Scratch, But You Can Find It at Most Grocery Stores or Online. Kwame's Recipe Is Included in The Cookbookwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Judge Trevor N. McFadden OpinionDocument38 pagesJudge Trevor N. McFadden Opinionwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Public Defender Service For DC Lawsuit Against BOP Alleging Unequal TreatmentDocument33 pagesPublic Defender Service For DC Lawsuit Against BOP Alleging Unequal Treatmentwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lawsuit by Family of Darryl BectonDocument29 pagesLawsuit by Family of Darryl Bectonwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- D.C. Court of Appeals On McMillanDocument7 pagesD.C. Court of Appeals On McMillanwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- FordBecton Complaint Filed in Arlington, VA Circuit Court On 03.11.2022Document29 pagesFordBecton Complaint Filed in Arlington, VA Circuit Court On 03.11.2022wamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Federal Judge Dismissal Lucas Vinyard and Alejandro Amaya - Ghaisar CaseDocument7 pagesFederal Judge Dismissal Lucas Vinyard and Alejandro Amaya - Ghaisar Casewamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Lawsuit Alleging Pattern of Racial and Gender Discrimination in MPD Internal AffairsDocument56 pagesLawsuit Alleging Pattern of Racial and Gender Discrimination in MPD Internal Affairswamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- Karon Hylton-Brown LawsuitDocument60 pagesKaron Hylton-Brown Lawsuitwamu885Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Topic 1 REED 4Document10 pagesTopic 1 REED 4Charmaigne Lee De GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Complete ThesisDocument39 pagesComplete ThesisÀ Ç K KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Kathryn Kuhlman - The Holy SpiritDocument1 pageKathryn Kuhlman - The Holy SpiritAnonymous tXpFHNGo7Q100% (5)

- You Alone - ChordsDocument2 pagesYou Alone - Chordsjamesdeanvernon100% (3)

- HISTORY OF MALAYEP UMCDocument2 pagesHISTORY OF MALAYEP UMCSison RogePas encore d'évaluation

- Growth Resources Reading List: For The Mid-Size CongregationDocument25 pagesGrowth Resources Reading List: For The Mid-Size Congregationronan.villagonzaloPas encore d'évaluation

- Association of Grace Baptists (East Anglia) Handbook 2014-15Document43 pagesAssociation of Grace Baptists (East Anglia) Handbook 2014-15Gareth RussellPas encore d'évaluation

- Book Sayfo EnglishDocument23 pagesBook Sayfo EnglishSandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Religious Consolidation and RenewalDocument4 pagesReligious Consolidation and RenewalMihai AdrianPas encore d'évaluation

- RevelationDocument51 pagesRevelationRahul NaiduPas encore d'évaluation

- Gods and Goddesses of Ancient EgyptDocument365 pagesGods and Goddesses of Ancient EgyptChild of Enoch94% (88)

- Signs & Symbols Myths & ReligionDocument77 pagesSigns & Symbols Myths & Religionalexandrasandu100% (1)

- Definition of Spiritual Gifts - Gifts TestDocument4 pagesDefinition of Spiritual Gifts - Gifts TestOni CtnPas encore d'évaluation

- A Course in Miracles Workbook Lesson 5Document6 pagesA Course in Miracles Workbook Lesson 5iafafzhfg100% (2)

- Script For The Christmas PartyDocument4 pagesScript For The Christmas PartyEngelie Cordova ArongPas encore d'évaluation

- Primary Source Analysis PPT PresentationDocument12 pagesPrimary Source Analysis PPT PresentationKyungstellation KS80% (5)

- Palawan Studies - ReviewerDocument16 pagesPalawan Studies - ReviewerKatrina Sarong AmotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Maximón: The Shape Shifting Trickster Provides HopeDocument63 pagesMaximón: The Shape Shifting Trickster Provides HopeEduardo ValenzuelaPas encore d'évaluation

- Does God Owe You A MiracleDocument4 pagesDoes God Owe You A MiracleAkindele O AdigunPas encore d'évaluation

- Impact of Monasticism on Medieval EducationDocument6 pagesImpact of Monasticism on Medieval EducationHarlene ArabiaPas encore d'évaluation

- #17. Heat of The Desert or The Safety of The Slave CampDocument10 pages#17. Heat of The Desert or The Safety of The Slave CamphnonachoPas encore d'évaluation

- A Search For God, Book 3Document46 pagesA Search For God, Book 3EricPas encore d'évaluation

- Blessing of A BellDocument2 pagesBlessing of A BellSev BlancoPas encore d'évaluation

- January: We TH FR Mo Tu Sa SuDocument12 pagesJanuary: We TH FR Mo Tu Sa SuDiana ManoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Kingdom (Reign or Dominion) of God: What Does This Mean?Document19 pagesThe Kingdom (Reign or Dominion) of God: What Does This Mean?Ifechukwu U. Ibeme100% (1)

- Gatekeepers of Heaven Earth LightDocument43 pagesGatekeepers of Heaven Earth Lightdreampurpose97Pas encore d'évaluation

- Portarlington Parish NewsletterDocument2 pagesPortarlington Parish NewsletterJohn HayesPas encore d'évaluation

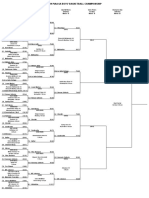

- 2019 PIAA Boys Basketball Tournament Brackets: Elite 8Document6 pages2019 PIAA Boys Basketball Tournament Brackets: Elite 8PennLivePas encore d'évaluation

- The Mystery of The Greek Letters A ByzanDocument9 pagesThe Mystery of The Greek Letters A ByzanExequiel Medina100% (2)

- What A Beautiful NameDocument1 pageWhat A Beautiful NameJosiel Nascimento - Eventos Musicais100% (1)