Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Greener Textile Chemistry

Transféré par

Au SanDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Greener Textile Chemistry

Transféré par

Au SanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

doi: 10.1111/j.1478-4408.2011.00346.

Progress towards a greener textile industry

Tim Dawson

Heron Lea, 18 Hall Lane, Sutton, Maccleseld, Cheshire SK11 0DU, UK Email: timldawson@aol.com

Many of the principles of the relatively new science of Green Chemistry, which aims to use resources efciently and minimise waste, are applicable in the eld of textiles. Improving product quantity and reducing environmental impact in the production and subsequent coloration of textile bres is a realistic goal. Public interest in organically produced natural bres has followed on from that in organically grown food, although the market for organic bres is still relatively small. In recent years, bre manufacturers have played their part in introducing a number of more ecologically regenerated cellulosic bres, as well as new totally synthetic polymer bres based on renewable raw materials. The methods that can be adopted aimed at reducing the environmental impact of bre, dye manufacture and subsequent coloration processes, are described with particular reference to these newer bres.

Coloration Technology

Review article

Society of Dyers and Colourists

Tim Dawson is fully retired, but enjoys keeping up to date with scientic developments, particularly those concerning colour, and writing articles based on his studies in the hope that it interests the readers of Coloration Technology.

Introduction

During the past decade, increasing attention has been paid by manufacturers, retailers and the general public to ecological, ethical and general health issues. Energy costs have continued to rise, additional legislation concerning registration and handling of chemical substances has been implemented and retailers are responding to consumers concerns that they should supply goods which have been sourced under ethical trading conditions (including their transport). Present day ethical consumers tend to seek foods and textile goods from natural or organic sources, but still mistakenly believe that anything must be harmful if it contains chemicals or E-numbers, without appreciating that strict control systems of compliance are in place for their protection, and that even natural dyes have E-numbers [1,2]! At the same time as manufacturers have also been changing their attitudes, there has been an increasing awareness that many products could possibly be produced under better environmental conditions; for example, using less energy, attaining better yields, with less water or air pollution and generating less waste or fewer (or no) byproducts. There is now an international set of standards under the ISO14000 series concerning the assessment and improvement of environmental management within industry [3]. These encompass some aims of the new science known as green chemistry [4,5], many of which are directly applicable to the production of dyes and textile bres and their subsequent processing and use: synthetic methods should try to incorporate all reactants into the nal product; for example, the reaction A + B = AB is preferable to AX + YB = AB + XY (by-product); reactants, end products and any waste material produced should have low toxicity to humans or the environment and preferably be biodegradable;

organic volatile solvents should be avoided if possible, water being the preferred solvent; catalytic reagents are preferable to stoichiometric ones; energy requirements for both the initial manufacture and any subsequent processing should be minimised (e.g. conduct reactions at as low a temperature as possible); raw materials should come from a renewable source wherever possible; at end of its life it is preferable that the product is recyclable [6]. This review summarises recent development work, with specic reference to textiles, towards these goals. The requirements for producing natural bres to be classed as organic and the development and properties of newer, more ecologically acceptable, cellulosic and polyester bres is discussed.

Energy, water and chemical consumption in the eld of textiles

Quite apart from environmental considerations, the textile industry has long been aware that the cost of all fuels has been escalating rapidly since the oil crisis of the mid1970s [7] and this has been a powerful incentive for the development of machinery and processes which minimise its use. Thus, machinery manufacturers have developed dyeing equipment with minimal power requirements and water consumption, for example, which can produce satisfactory dyed fabric quality whilst operating at short liquor-to-goods ratios, with lower operating temperatures and shorter process cycles. Energy and water savings can start at the cloth preparation stage, for example by replacing the chemicals normally used for scouring the greige fabric by enzymic desizing agents [8]. Similarly, improvements can be made by greatly reducing the amount of dye in the efuent from dyehouses. With this in view, dye makers have, for example, introduced bifunctional reactive dyes with very high dye bre xation. This leads both to less dye being lost in the subsequent washing-off process, reduced water and detergent usage and easier treatment of efuent. In fact, in 2000 Dystar were awarded the UK Green Chemistry Award for their bifunctional, high xation, reactive dyes. When reactive dyes were rst introduced in 1956, the

1

2011 The Author. Journal compilation 2011 Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 128, 18

Dawson Progress towards a greener textile industry

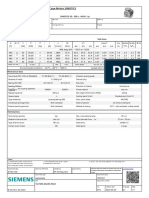

dichlorotriazine Procion MX dyes (now withdrawn from the range) were also bifunctional, but these dyes did not have high enough substantivity to give good exhaustion (e.g. an average of 40% at 30:1 liquor-to-goods ratio) prior to the alkali-xation stage during batchwise dyeing, which limited the efciency of dye xation. These did of course have the desirable property (from a green chemistry point of view) of being applied at only 40 C. With present-day reactive dyes, the nal removal of the relatively small quantities of any unxed, hydrolysed reactive dyes, along with the alkali and salt retained in the dyed bre, can be achieved using just plain water (i.e. containing none of the conventionally recommended detergent), resulting in an appreciable reduction in the biological load of the efuent [9]. Considerable energy can still be saved by optimising dyeing conditions, using automated time temperature controls etc. and, in general, by a regime necessary for right rst time dyeing results [10,11]. One must also bear in mind the energy consumed in the initial production of the textile bres themselves (Table 1). An even more fundamental question is which particular (mainly nite) basic source of power will be used in the future [12]. Many nations are attempting to plan for an advanced power generation plant with minimal pollution and the inevitable cost increases in power generation, whether from coal, oil, natural gas, or the more ecologically acceptable wind, tide or wave power. Recent world events are delaying pressing decisions on the renewal expansion of nuclear energy, whilst ecological considerations support the installation of many more wind-generating units, despite the frequent inability of land-based units to operate efciently. All these issues are discussed in a recent publication [13].

be eco-friendly because they are produced from renewable resources, have no associated chemicals that are potentially harmful to the environment (including possible gaseous release to the atmosphere or in the resulting efuent) and consume relatively low amounts of energy during their production. These are the main factors which have determined development of most bres that have been introduced during the past 20 years. There is now a plethora of national and international organisations involved in setting criteria and awarding certication of organic products, namely: The Oeko-Tex Association The Oeko-Tex Standard 1000 is a means of certifying that an acceptable level of environmental and ethical control is maintained during the production process [15]; The Internationaler Verband der Naturtextilwirtschaft (IVF) label is awarded to producers who can demonstrate controlled production methods right from the original bre to the nished garment [16]; The Organic Trade Association (USA) and the Soil Association (UK) promote labelling schemes for organic natural bres only [17]; The Organic Crop Improvement Association (OCIA) provides research and certication services to organic growers in North America and the European Union on a very wide range of produce [18].There are also many labelling schemes for organic produce such as Blue Sign (Swizerland), EcoCert (France) and EcoLabel (EU). Organic natural bres Cotton production remains very high (over 25 million tonnes per annum), but the growing of cotton crops requires very intensive irrigation (up to 20 000 l of water per kg of cotton) and employs large quantities of pesticides and insecticides for crop control (25 and 11%, respectively, of total world consumption) [19]. At present, to be classed as organic, the cotton bre used to produce a fabric must have been grown from genetically unmodied seed varieties and without the use of herbicides or pesticides, whilst maintaining ethical labour employment standards. Large quantities of cotton are produced today based on a genetically modied, pest-resistant strain referred to as Bt cotton, the genes of which have been modied by insertion of the gene of a pest toxin Bacillus thuringiensis. Although being more productive, particularly in India [20], and requiring greatly reduced use of pesticides, Bt cotton is regarded as less natural [21]. In consequence, genetically modied cotton is not classed as organic, but the pest-resistant strains do offer an additional environmental benet, in that the incidence of accidental, but widespread, pesticide poisoning of eldworkers has been found to be greatly reduced [22]. Some major jeans and sportswear manufacturers are promoting organic cotton garments, but in 2010 the global production of this bre (in over 20 countries, but particularly in India) was only 1.1% of total world cotton production [23]. Because of the various negative social and environmental aspects of cotton cultivation worldwide, the Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) association has been set up (www.bettercotton.org) to foster improvements in the sustainability of cotton production methods.

Research and development for more eco-friendly bres

Natural bres The upsurge in interest for all things ecological has affected ethical shoppers interest in organic textile bres, preferably those that may also be classied as natural, i.e. not synthetic; namely, cotton, wool, silk, linen, jute and bamboo. Some synthetic bres may be considered to

Table 1 Energy requirements for producing textile bre [14] Energy required tonnes (GJ)a 10 15 55 65 100 115 125 65 175 250

Fibre Flax Cotton (organic) Cotton Wool Viscose Polypropylene Polyester Recycled polyester Acrylic Nylon

a One gigajoule (GJ) is equivalent to 280 kilowatt hours (kWh)

2011 The Author. Journal compilation 2011 Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 128, 18

Dawson Progress towards a greener textile industry

To be classed as organic, wool must have been sheared from sheep given organic feed and raised without the use of hormones or pesticides. This poses problems in the prevention of blowy strike, when the usual sheep dipping is not allowed. In some markets, it would appear that natural dye materials must also have been used to dye organic wool garments! As wool textiles constitute less than 2% of total textile bre production, it is not surprising to see that the production of organic wool remains very small. The same is true for organic silk, which must not only be obtained by feeding the silkworms with the leaves from mulberry bushes that have been grown organically, but in which no cruelty has been employed (i.e. not by the conventional production method of placing the cocoons containing the live worms into boiling water). Thus, in the so-called peace or vegetarian varieties, the silkworms are allowed to develop and emerge as moths. As a consequence, the silk threads now have discontinuities, so the yarns have to be processed as a staple bre such as cotton, yielding a fabric with a different appearance and handle, but which has a warmer feel. Other natural bres There is quite an assortment of other bres that have been traditionally used or have more recently been promoted because of their apparently green credentials. Amongst traditional bres are jute, ramie, coir, hemp and sisal, whilst bamboo, corn, pineapple, banana and soya bean protein bres have been promoted more recently. With the exception of jute, world production of the remaining bres capable of being used as general textile bres is very small, and the wet fastness properties attainable on some of these when dyed is only moderate. The bre obtained from soya bean protein is, however, being manufactured for textile use in China and is dyeable with either acid or reactive dyes [24], which can in fact also be used to colour all traditional bast bres. The greatest quantity of bast bre grown (mainly in the Indian continent) is jute, but this is not a satisfactory bre for producing personal apparel. Yarns spun from linen, however, have long been available, whilst very recently organic bamboo bre, produced mainly in China, has become available. Both bres may be spun on the ax system. Bamboo cane grows extremely quickly and with minimal irrigation. In addition, it requires no pesticides as it is naturally disease resistant. Bamboo bre can also be specially processed, by using enzymic retting and modied scutching processes, to have certain desirable properties such as a soft, silky handle [25], and it is inherently antibacterial, breathable, very absorbent and thus cool to wear. If these bres are then ring- or worsted-spun they can be used in blends with cotton or wool for underwear, T-shirts and socks. Synthetic cellulosic bres Regenerated cellulosic bres have been produced since the early 1900s, by wet spinning a viscous solution of cotton linters or bleached wood pulp, using either the cuprammonium method (for cupro rayon), or the more important carbon disulphide caustic soda dissolution process, in which the cellulose xanthate dope is extruded

through a spinneret into an acidic coagulating bath, the bres so formed being stretched during winding off. The xanthate process is still used to produce most conventional viscose rayon textile bres [26]. Both traditional methods involve the use of chemicals that could be environmentally harmful (e.g. heavy metals ammonia or carbon disulphide sodium hydroxide). Many improvements in the production of xanthate viscose have been made by rms such as Lenzing to reduce the environmental impact of this process. Although standard viscose rayon was relatively cheap and gave fabrics a pleasing handle and good draping properties, the materials produced were inferior to similar cotton ones as they tended to crease badly (unless a resin nish was applied) and had inferior wet strength and abrasion resistance. From the 1960s onwards, Courtaulds developed several improved forms of viscose, including the high wet modulus (HWM) polynosic bres, such as Vincel 28 and the modal bre Vincel 64, obtained by changes either to the choice of the type of wood pulp and or to the viscose spinning conditions, together with Evlan, a chemically crimped carpet bre with improved abrasion resistance. Modern regenerated cellulose bres Neither of the two classical viscose rayon production methods, by which cellulosic bres are regenerated chemically, can be considered to be environmentally friendly because, despite using a renewable raw material (wood pulp) they still require very large quantities of water, the efuent must be treated to recover large quantities of sodium sulphate and the toxic sulphide gases that are released need strict control. As a consequence, revised spinning systems were urgently needed. This resulted in research towards the development of a new physical regeneration process based on a recyclable, nontoxic, solvent-based spinning method using Nmethylmorpholine-N-oxide (NMMO) to produce the new lyocell bres. In 1991, this process was rst used in the UK by Courtaulds (subsequently Acordis Tencel) to produce Tencel bre and nowadays by Lenzing AG of Austria. Compared with conventional viscose rayon, lyocell bres have superior wet and dry strength and the derived fabrics are more crease-resistant. This change in technology is another example of green chemistry, in that the former environmental pollution problems have been minimised because the N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide solvent used can be efciently recovered and recycled. Because of their very high degree of crystallinity compared with other cellulosic bres, unmodied lyocell type bres can be easily brillated by any mechanical action on the woven fabric surface (e.g. during winch or jet dyeing in rope form or during mechanical washing processes). This may lead to undesirable effects [27], but it is useful for the production of the popular suede or peach-skin surface effects attained by using a combination of enzymic treatment and mechanical abrasion (which may be produced by the dyeing method itself or using special equipment) [28]. As a consequence, lyocell bre has become very popular for certain styles; for example, the production of fashionable jeans or jeggings that have a pleasing softer handle compared with cotton ones. Similarly, the mechanical agitation of garment dyeing

3

2011 The Author. Journal compilation 2011 Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 128, 18

Dawson Progress towards a greener textile industry

produces a soft, warm nish. Fibrillation was, however, a problem if a crisper, more formal garment appearance was required. Such fabrics were therefore dyed in open width or alternatively treated with a bifunctional resin such as dimethylol-dihydroxyethyleneurea (DM-DHEU) before making into garments for subsequent piece dyeing [29]. Lyocell cotton blends dyed using reactive dyes proved popular, whilst the dyeing of blends with both polyester and silk to yield either solid or cross-dyed effects has also been shown to be feasible [30]. Non-brillating types of lyocell bre, such as Courtaulds Tencel A100 and Lenzings Lyocell LF, have also been produced by chemically crosslinking the hydroxyl groups in the cellulosic bre polymer chains during the wet-spinning stage of manufacture (i.e. using, for example, a trifunctional compound triacrylamido trihydroxytriazine [31]. During the past decade, extensive further research into potential crosslinking agents has been carried out at the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) [32]. Thus, for example, brillation can be minimised by treating the bre with Sandospace R, a colourless dichlorotriazinyl resist agent [33]. Varying degrees of protection from brillation could also be achieved when the bre was dyed with certain bis-monochlortriazinyl or bis-vinylsulphone type dyes [34,35] and with an even more reactive sulphatoethylsulpho-dichlorotriazine reactive dye [36]. In addition, some benzene bisacrylamido compounds appear to be suitable as crosslinking agents that remain stable under the high temperature dyeing conditions required for polyester lyocell blends [37]. Fibrillation problems are, however, much less common today as a result of a greater knowledge of the effect and the exercise of closer control of processing conditions. The xation and colour yield obtained when a monofunctional reactive dye was applied by ink-jet printing has also been studied in comparison with that on cotton. It was found that, as in conventional reactive dyeing, irrespective of differences in the degree of dye xation, a higher colour yield was achieved on standard Tencel (but not Tencel A100) compared with that on cotton, even though the cotton fabric had been mercerised [38]. One other new type of regenerated bre is a viscose which uses bamboo as its raw material in place of wood pulp. Bamboo grows in many regions over the world extremely rapidly, in favourable conditions reaching its full height in approximately 10 weeks. In addition, its land requirements are modest and yields of ca. 20 tonnes per acre can be attained compared with 12 tonnes for cotton bre. In view of the cultivation properties of bamboo cane, it is clear that this is a slightly more acceptable, easily renewable source of cellulose bre. Bamboo, like other grasses has, however, a relatively high silica content that requires special alkaline pretreatment when the pulp is prepared for the subsequent xanthate process. Production of regenerated bamboo bres is likely to remain small in view of the present trend to manufacture synthetic cellulosic bres, such as viscose, modal or lyocell using wood pulp from forests managed to the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and Programme for the Endorsement of Forestry Certication (PEFC) certicate schemes.

4

Synthetic eco-bres The most important synthetic bre produced today is polyester, which constitutes ca. 60% of world bre production, and approximately half of this is made in China. Polyester is manufactured using entirely petrochemical-based feedstocks and requires large energy inputs for its synthesis from terephthalic acid and ethylene glycol. Polyethyleneterephthalate (PET) polyester from plastic bottles can be economically recycled, but reuse is at present limited by the availability of suitable recycling plants. In the USA, where polyester is more commonly used in carpets than is the case in European markets, waste PET from bottles is being recycled and re-spun (after blending with virgin PET polymer chips for bre extrusion) to be used as carpet yarns. The production of recycled polyester requires only approximately half the energy that is needed to make an equivalent amount of virgin bre, but there are some lingering questions as to the possible release of antimony trioxide used as the original polymerisation catalyst [14]. A somewhat bizarre possibility is the possible use of waste PET as a source of novel disperse dyes [39]. Other polyester bres Some progress has been made in producing a polyester bre that is partly based on non-petrochemically derived materials. DuPont launched a new polyester polymer, based on terephthalic acid and propylene glycol (1,3propanediol, or PDO) rather than ethylene glycol (1,2ethandiol), which they have named Sarono [40]. This polymer is therefore polytrimethyleneterephthalate (PTT), which is also produced by the Shell Chemical Company under the name of Corterra. PTT can be manufactured and melt spun in the same plants as those used to produce PET polymer and the melt-spun bre. Sarono PTT is, however, a more ecologically friendly bre than Corterra because the process used to make the propylene glycol for the former is based on the biological fermentation of a renewable source material, namely cornstarch sugars [41], whilst the glycol used for Corterra is made from a petrochemical, ethylene oxide [42]. The catalytic polymerisation process for PTT is in two stages; namely, the formation of oligomers with up to six pairs of 1,3-propanediol terephthalate ester groups, followed by polycondensation, in the presence of an organo-titanium catalyst, yielding PTT. Compared with PET, PTT has lower glass transition and melting point temperatures, namely 5060 vs 75 C and 225230 vs 285295 C. Sarono can therefore be dyed using disperse dyes at 100 C. Neither of the above polyester bres can be considered to be fully chemically green and the only alternative synthetic bre to have been developed recently that can is polylactic acid (PLA), because its raw material, lactic acid, is made by a biological fermentation process using a renewable raw material, namely corn. Polylactic acid bre Lactic acid can be produced from renewable carbohydrates such as dextrose derived from corn starch or sugar cane by a bacterial fermentation processes, and

2011 The Author. Journal compilation 2011 Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 128, 18

Dawson Progress towards a greener textile industry

thus the raw materials are both renewable and nonpolluting. PLA cannot, however, be made by direct polymerisation of this acid and therefore a cyclic dilactide ester is rst produced and this is then polymerised in the presence of a catalyst (usually stannous octanoate) (Figure 1). Lactic acid can exist as both D(-) and L(+)-stereoisomers, so several stereochemical forms of the dilactide can exist and this affects the physical properties of the nal polymer. If the L,L-dilactide is polymerised, it produces a PLA with a melting point of ca. 170 C and glass transition temperature of 65 C, which, like those of PET, are considerably lower than those of polyester. This again affects the dyeing and nishing conditions and consumer after-care (such as ironing temperatures) of PLA fabrics [43]. The temperature sensitivity properties of PLA bre (called Ingeo by its producers; Nature Works, USA) can, however, be varied by adjusting the proportions of D- and L-isomers in its polymer chains. Nevertheless, Ingeo bre is considered to possess many mechanical properties similar to those of PET bres, but unlike polyester, PLA bre is biodegradable and its production is said to require 2050% less fossil fuel resources than comparable petroleum-based bres. PLA bre can be dyed with selected conventional disperse dyes used for polyester, and dyeing is conducted under pressure, but at 110120 C rather than 130 C normally used for polyester. Careful dye selection is necessary as some dyes, particularly amongst the anthraquinones, show poor exhaustion. Medium energy azo disperse dyes perform best on PLA bre and anthraquinone dyes possessing aliphatic side-chains have better exhaustion properties [44]. One particular problem that has been identied is that benzodifurone red dyes, which on PET bre yield bright red shades of very high wet fastness, have poor exhaustion properties on PLA bre because of their poor solubility and slow rate of dyeing at the lower dyeing temperatures which PLA requires. A comparison of the colour yield obtained on PLA bre as compared with that on polyester showed that most azo disperse dyes appeared stronger on the former bre, which was in agreement with their solution appearance in the more polar solvent ethyl acetate compared with methyl benzoate, chosen to reect the polar properties of the two bres [45]. There is a further difculty in producing heavy shades, such as blacks and navy blues. As a possible solution to this problem, dyeing from supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO2) has been examined. Dye application at 8090 C for 1 h at 280-bar pressure gave strong dyeings both at the laboratory and on a technical plant scale [46], but residual dye remaining on completion of the process resulted in surface precipitation and inferior rub fastness. Treatment

O H3C O O CH3 HO O

with fresh supercritical carbon dioxide (in an attempt to clear surface dye) gave an unacceptably blotchy effect. By contrast, supercritical carbon dioxide package dyeing of conventional PET bres has been successfully carried out on a routine basis for the last decade [47,48]. In view of the potential usage of PLA cotton blended bres, the effect of prescouring, followed by a simulated one- and two-stage dyeing and the reduction clearing process was assessed, the only potential stability problem identied being that of using prolonged dyeing times, particularly under alkaline conditions [49,50]. The same limitations apply to the dyeing of PLA silk blends when using disperse and reactive dyes [51]. If made from continuous lament (as opposed to spun bre), PLA fabrics must be heat set, prior to dyeing, by treating at 125130 C for 3045 s [52]. As with polyester, the dyed PLA fabric must be given a reduction clear to ensure optimum wash fastness of the nal dyeing. No problems were found with alkali- or acid-sensitive disperse dyes, irrespective of the pH of the reduction clearing treatment, although optimum results are assured if the amount of air present during this process is minimised [53].

Improvements to traditional dyeing methods

Textile processing equipment Quite apart from the need to minimise energy and water usage, recorded weighing systems, strict control of cloth quality and dye selection, and instrumental control of the dyeing processes are all essential for reproducible, rightrst-time results. Machinery manufacturers have long considered the energy costs entailed in using the various types of dyeing and nishing machines, whether for batchwise or continuous operation. The best batchwise dyeing machines operate at low liquor-to-goods ratios (LGR) to reduce energy and water consumption, and, for example, for knitgoods in particular, one has the choice between three types of jet dyeing machines These are generally classed as Overow (LGR 10:1), Airow (LGR 5:1) or Softow (LG 1:1), the heat requirements varying accordingly [52]. When the dyed goods are nally dried, strict control, which can be achieved with modern dryers tted with active, multi-point temperature humidity sensors, is essential to prevent the considerable wasted energy that over-drying entails. It must also be remembered that leaving a drier idling between batches wastes energy, particularly if the circulation fans are still running. Sulphur dyes Sulphur dyes continue to be an important class of colour for economic reasons, particularly CI Sulphur Black 1, which still has an annual consumption of ca. 15 000 tonnes. The conventional reducing agent that has been used with these dyes was sodium sulphide and, although various methods were devised to decrease its usage rate, this still resulted in unacceptable quantities (> 2 ppm) of sulphide being present in the efuent. As a result, a more environmentally friendly reducing agent, glucose, is now widely used. Sulphur dyes require a reducing agent

5

CH3 O

O O CH3 n

CH3 OH O

O Dilactide ester

Figure 1 Production of polylactic acid

PLA polymer

2011 The Author. Journal compilation 2011 Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 128, 18

Dawson Progress towards a greener textile industry

having a redox potential of some minus 650750 mV for optimum colour yield, but it has been found difcult to study the actual chemical changes that occur during dyeing because the CI Sulphur Black 1 dye molecule has more than one potential reduction site [53]. Using glucose-type reducing agents not only greatly improves the quality of the efuent but has actually been shown to give better quality dyeings compared with those produced using sulphide-based reducing agents [54]. After-chrome dyes The extensive use of chrome dyes for wool diminished greatly after the introduction of 1:1 and particularly 1:2premetallised dyes over 50 years ago. Just as is the case with sulphur dyes, the use of a chrome black, such as CI Mordant Black 9, is still the most economical way of producing economic blacks with excellent fastness properties. Traditionally, after-chroming was carried out using excess potassium dichromate. Hexavalent chromium species are, however, environmentally hazardous to human health and, following the introduction of stricter regulatory controls, the traditional chrome dyeing method was modied to reduce the amount of chromium in the efuent; for example, by using trivalent chromium complexes and an a-hydroxycarboxylic acid such as lactic acid [55]. The traditional methods also resulted in wool bre containing excess chromium that adversely affected spinning and weaving characteristics, quite apart from the chromium content in efuent being as high as 100 mg l, some 100 times higher than the permitted level. It had been previously shown, however, that, whilst still using potassium dichromate but exercising much more careful process control, satisfactory levels of residual chromium could be attained [56]. Nowadays, for other fast, dark shades on wool, premetallised dyes are used, but there are some questions as to whether even these are acceptable, despite the fact that they release none of their chromium into the environment, as the metal remains part of a stable coordination complex dye until the dyed textiles nal disposal. Disperse dyes One aspect of the application of disperse dyes to polyester bres, where it is possible to improve efuent loading, is to eliminate the use of sodium hydrosulphite in the reduction clearing after-treatment process. This was rst achieved by ICI with the availability of disperse dyes that carried carboxylic ester groups, namely the Procilene PC and later the Dispersol PC dyes, the latter being used as ground shades for illuminated discharge printing styles [57]. More recently, phalimide- and naphthalimide-containing azo disperse dyes have also been shown to yield dyeings on polyester with good wetfastness properties (although the authors did not quote any light-fastness data) when using only an alkali afterclearing treatment [58,59].

is a limit to what can be achieved at present and, inevitably, a textile mill will still produce quantities of aqueous efuent. In particular, the presence of residual dye, which used to be particularly evident before reactive dyes with high xation properties were developed, is an obvious problem. Thus, in larger production units, the efuent is sometimes pretreated, usually by a occulation settling process, before the efuent passes to the local authority sewage treatment plant. However, this then produces another problem, i.e. the disposal of the sludge so produced. One possible in-house method, involving a combination of membrane technology and biological treatment, seems to offer the possibility of producing efuent capable of reuse for dyeing, although allowance would still have to be made on account of the relatively large amount of salt that may be present after this treatment [60]. Other possibilities of using recycling processes have been reviewed [61]. A wide variety of chemical methods can be used to decolorise dyeing efuent and these are mainly oxidative ones, using for example hydrogen peroxide, sodium hypochlorite or treating with ozone [62], but attention has increasingly been given to the use of biological methods of degradation, such as those using specic fungal bacteria or enzymes [63,64]. Some low-cost adsorbents can also prove effective for colour removal [61]. It is not the intention in this review to cover this very wide eld in any detail, but a variety of reviews of other techniques have been published [65].

Future developments

Novel coloration systems Mass coloration of polymers is a logical method of coloration as it can usually be carried out in a very controlled manner with minimal pollution and yield shades with excellent light and wet fastness. It is, however, a much less exible process commercially and the colour range produced needs to be carefully chosen to avoid large stockholding, but it is viable for certain large volume shades such as blacks. Mass coloration was used to a limited extent with polyester and acrylics and is still largely the only method of producing fast colours on polypropylene bres. However, it has recently been demonstrated that it is possible to permanently colour PLA bres during manufacture by using a catalyst containing a suitable chromophore for the polymerisation process itself. The so-called DyeCat process [66] enables even deep shades to be attained with good fastness properties, but again such a process will only be of interest if much larger quantities of PLA bres are produced. Even then, its use would probably only be of interest for, say, blacks and navy blue shades, which are at present difcult to produce by conventional dyeing. Despite the development of reactive dyes having high degrees of xation, the dyeing process still requires considerable quantities of salt and alkali, which add to the efuent load. One novel method of overcoming this problem was demonstrated some years ago, but does not so far appear to have had reported commercial success; namely, the pretreatment of the cellulose bre with special cationic agents. Pretreatment with some cationic polymers

Efuent treatment

However much improvement is made in rendering coloration processes more environmentally benign, there

2011 The Author. Journal compilation 2011 Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 128, 18

Dawson Progress towards a greener textile industry

allows both exhaustion and xation of the dye without the use of either salt or alkali, to yield dyeings with excellent wash-fastness properties [67]. Using another polymer (a polymeric polyvinylpiridinyl compound), it was also shown that even 1:2 premetallised dyes could also be satisfactorily xed on cotton to yield dyeings with very high wet and light fastness [67] Experienced cotton dyers might take some convincing that such good results could be achieved using premetallised dyes, as the dyes are thought to be bonded to the polymer on the bre largely by ionic and van der Waals type forces. Pretreatment of cotton with 3-chloro 2-hydroxypropyltrichlormethyl ammonium chloride also allowed monofunctional reactive dyes to attain very high xation [68]. Another interesting development in the reactive dyeing of cotton used the supercritical carbon dioxide method to apply unsulphonated diuorotriazine dyes under mildly acidic conditions, to attain excellent fastness properties and 100% xation [69]. This type of process requires dyes which are soluble in the dyeing medium (e.g. it is suitable for the application of disperse dyes on polyester), but for other natural bres it has been demonstrated that dyeing can be carried out successfully using reactive dyes and minimal additions of water and this method has also been applied to one-bath dyeing of polyester cotton blends using reactive disperse dyes [70]. The textile printing industry was at one time considered to be one of the worst offenders with regard to both its aqueous and gaseous efuent discharge. The introduction of digital ink-jet printing processes, particularly those using pigments, was thought to offer, not only an economic means of achieving fast-response and short print runs, but also one which would be judged as more ecologically friendly compared with conventional screen printing. In the event, however, digital printing still awaits the availability of more productive printing devices. Consequently, jet print output is presently estimated to be no more than 1% of the total print market (which again is dominated by China and India) [71].

garments are labelled just as polyester that might give sales a boost. In the developed world greater progress has, nevertheless, been achieved in diminishing pollution, both atmospheric and in waste disposal. It is, however, interesting that the two countries having the largest production capacities for both bres and dyes, namely China and India, where environmental conditions are generally considered to be poor, not only lead the world both in production of organic cotton and other eco-bres, but also carry out and publish so much research that has an ecological background. Yet, there are some serious exceptions and Greenpeace International have called on some EU brand distributors to show more responsibility in their sourcing, in view of serious water pollution by some Chinese textile producers [72].

References

1. T L Dawson, Color. Technol., 124 (2008) 67. 2. J Emsley, Healthy, Wealthy, Sustainable World (Cambridge: RSC Publishing, 2010). 3. O Boiral, Organ. Sci., 18 (2007) 127. 4. J A Linthorst, Found. Chem., 12 (2010) 55. 5. N Winterton, Chemistry for Sustainable Technologies: A Foundation (Cambridge: RSC Publishing, 2010). 6. Y Wang (Ed.), Recycling in Textiles (Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing, 2006). 7. T L Dawson, J.S.D.C., 98 (1982) 387. 8. P W Nielsen, H Kuilderd, W Zhou and X Lu, Sustainable Textiles: Lifecycle and Environmental Impact, Ed. R S Blackburn (Oxford: Woodhead, 2009) 33. 9. S M Burkinshaw and O Kamambe, Dyes Pigm., 77 (2008) 384. 10. J Park, Rev. Prog. Col., 34 (2004) 86. 11. J Park and J Shore, Color. Technol., 125 (2009) 133. 12. J W Tester, E M Drake, M J Driscoll, M W Golay and W A Peters, Sustainable Energy (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005) 137. 13. V Balzani and N Armaroli, Energy for a Sustainable World (Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, 2010) 125231. 14. O ecotextiles, (online: http://oecotextiles.wordpress.com/2009/ 07/14/; last accessed, 26 August 2011). 15. Oeko-Tex Association, (online: http://www.oekto-tex.com; last accessed, 26 August 2011). 16. Internationaler Verband der Naturtextilwirtschaft (IVF), (online: http://www.naturtextile.com; last accessed, 26 August 2011). 17. Organic Trade Association (USA) and the Soil Association (UK), (online: http://www.soilassociation.com; last accessed, 26 August 2011). 18. Organic Crop Improvement Association (OCIA), (online: http://www.ocia.org; last accessed, 26 August 2011). 19. L Grose, Sustainable Textiles: Lifecycle and Environmental Impact, Ed. R S Blackburn (Oxford: Woodhead, 2009) 33. 20. M Qaim and D Zilberman, Science, 299 (2003) 900. 21. G D Stone, World Dev., 39 (2011) 387. 22. S Kouser and M Qaim, Ecol. Econom., 70 (2011) 2105. 23. Textile Exchange, Organic Cotton Farm and Fibre Report 2011 (online: http://www.textileexchange.org/OrganicExchange-Publications.html; last accessed, 26 August 2011). 24. J H Choi, M J Kang and C Yoon, Color. Technol., 121 (2005) 81. 25. Litrax (Switzerland), (online: http://litrax.com; last accessed, 26 August 2011). 26. C Woodings, Regenerated Cellulose Fibres (Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing, 2000) 1. 27. P Goswami, R S Blackburn, J Taylor, S Westland and P White, Color. Technol., 123 (2007) 387. 28. K P Mieck, M Nicolai and A Nechwatal, Melliand Textilber. Int., 5 (1997) E69. 29. J M C Taylor and G W M Collins, USP6949126 (Lenzing Fibres, UK; 2005).

Conclusion

There is no doubting the general agreement that a more sustainable future must be an objective we should strive for and, in the eld of textiles, progress has been slow but steady. There is today a much greater awareness of ecological and ethical issues than a decade ago, although the willingness to buy organic produce is increasingly dictated by price. The general public seem to agree they would prefer to purchase organic, eco-friendly goods and are willing to pay a premium, but only 1015% extra! The problem is therefore one of economy of the scale of production and this is evident from the slow progress being made by organic natural bres as well as the newer bres covered in this review, with all of which small production volume mitigates against a lower price. One further aspect that might be hindering acceptance of, say, lyocell fabrics may lie in the bre labelling system, which still categorises them as viscose, a bre which older members of the public might still associate with poor performance as compared with cotton. In contrast, if PTT

2011 The Author. Journal compilation 2011 Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 128, 18

Dawson Progress towards a greener textile industry

30. H D Joshi, D H Joshi and M G Patel, Color. Technol., 126 (2010) 194. 31. T R Burrow, Lenzinger Berichte, 84 (2005) 110. 32. I Bates, E Maudru, D A S Phillips and A H M Renfrew, Color. Technol., 122 (2006) 270. 33. D A S Phillips, R Reisel and A H M Renfrew, Color. Technol., 124 (2008) 17. 34. I Bates, R Ibbett, R Reisel and A H M Renfrew, Color. Technol., 124 (2008) 254. 35. I Bates, D A S Phillips, A H M Renfrew and T Rosenau, Color. Technol., 123 (2007) 18. 36. A H M Renfrew and D A S Phillips, Color. Technol., 119 (2003) 116. 37. Y Su, A H M Renfrew, D A S Phillips and E Madru, Color. Technol., 121 (2005) 203. 38. A W Kaimouz, R H Wardman and R M Christie, Color. Technol., 126 (2010) 342. 39. V S Palecar, N D Pingale and S R Shikla, Color. Technol., 126 (2010) 86. 40. J V Kurian, J Polymer. Environ., 13 (2005) 159. 41. M Empage and S Haynie, EP1204755 (DuPont, USA; 1999). 42. C Hwo, H Brown, P Casey, H Chuah, H Dangayach, T Forschner, T Meorman and L Oliveri, Chem. Fibr. Int., 50 (2000) 53. 43. D W Farrington, L Lunt, S Davies and R S Blackburn, Biodegradable and Sustainable Fibres, Ed. S Blackburn (New York: CRC Press, 2005) 191. 44. O Avinc and A Koddami, Fibre Chem., 42 (2010) 68. 45. J Suesat, T Mungmeechai, P Suwanruji, W Parasuk, J A Taylor and D A S Phillips, Color. Technol., 127 (2011) 217. 46. E Bach, D Knittel and E Schollmeyer, Color. Technol., 122 (2006) 252. 47. M de Giorgi, E Cadoni, D Marricca and A Piras, Dyes Pigm., 45 (2000) 75. 48. E Bach, E Cleve and E Schollmeyer, Rev. Prog. Col., 32 (2002) 88. 49. D Phillips, J Suesat, M Wilding, D Farrington, S Sandukas, D Sawyer, J Bone and S Dervan, Color. Technol., 120 (2004) 35.

50. D Phillips, J Suesat, M Wilding, D Farrington, S Sandukas, J Bone and S Dervan, Color. Technol., 120 (2004) 41. 51. K Liu, Y Rui and G Chen, Adv. Mat. Res., 239242 (2011) 1739. 52. D Philips, J Suesat, M Wilding, D Farrington, S Sandukas, J Bone and S Dervan, Color. Technol., 119 (2003) 128. 53. O Avinc, Tex. Res. J., 81 (2011) 1049. 54. M White, Rev. Prog. Col., 28 (1998) 80. 55. T Bechtold, F Berthold and A Turcanu, J.S.D.C., 116 (2000) 215. 56. R S Blackburn and A Harvey, Environ. Sci. Technol., 38 (2004) 4034. 57. D M Lewis and G Yan, J.S.D.C., 111 (1995) 316. 58. G Meier, J.S.D.C., 95 (1979) 252. 59. T Do, J Shen, G Cawood and R Jenkins, Color. Technol., 121 (2005) 310. 60. G Cawood and J Scotney, Rev. Prog. Col., 30 (2000) 35. 61. G Crini, Biosource Technol., 97 (2006) 1061. 62. T Robinson, G McMullen, R Marchant and P Nigam, Bioresource Technol., 77 (2001) 247. 63. V Tigini, V Prigioni, P Giansanti, A Magiavillano, A Pannochia and G V Agathos, Biochem. Advan., 22 (2003) 161. 64. D Wesenberg, I Kariakides and S N Agathos, Biotechnol. Adv., 22 (2003) 161. 65. M Joshi and R Purwar, Rev. Prog. Col., 34 (2004) 58. 66. R O MacRae, C M Pask, L K Burdsall, R S Blackburn, C M Rayner and P C McGowan, Angew. Chem., 50 (2011) 29168. 67. R S Blackburn and S M Burkinshaw, Green Chem., 4 (2002) 47. 68. R S Blackburn and S M Burkinshaw, Green Chem., 4 (2002) 261. 69. M V Fernandez Cid, J van Sprosen, M van der Kraan, W J T Veuglers, G F Woerlee and G J Witkamp, Green Chem., 7 (2005) 609. 70. M Shingo, K Katasushi, H Toshio and M Kenji, Text. Res. J., 74 (2004) 9. 71. J Provost, The Colourist, 3 (2011) 4. 72. Greenpeace International, Dirty Laundry: Unravelling the Corporate Connections to Toxic Water Pollution in China (Amsterdam: Greenpeace International, 2011).

2011 The Author. Journal compilation 2011 Society of Dyers and Colourists, Color. Technol., 128, 18

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Collaboration Live User Manual - 453562037721a - en - US PDFDocument32 pagesCollaboration Live User Manual - 453562037721a - en - US PDFIvan CvasniucPas encore d'évaluation

- Basic Electrical Design of A PLC Panel (Wiring Diagrams) - EEPDocument6 pagesBasic Electrical Design of A PLC Panel (Wiring Diagrams) - EEPRobert GalarzaPas encore d'évaluation

- Promoting Sustainability Through Green Chemistry: Mary M. KirchhoffDocument7 pagesPromoting Sustainability Through Green Chemistry: Mary M. KirchhoffHernán DomínguezPas encore d'évaluation

- Recycling of Textile Waste Is The Best Way To Protect EnvironmentDocument7 pagesRecycling of Textile Waste Is The Best Way To Protect Environmentemigdio mataPas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial BiotechnologyDocument6 pagesIndustrial BiotechnologyJorge Alberto CardosoPas encore d'évaluation

- Cleaner Sustainable Production in Textil PDFDocument26 pagesCleaner Sustainable Production in Textil PDFtesfayergsPas encore d'évaluation

- Recycling of Plastics - A Materials Balance Optimisation Model PDFDocument14 pagesRecycling of Plastics - A Materials Balance Optimisation Model PDFLeoChokPas encore d'évaluation

- Plastic Waste Management: Is Circular Economy Really The Best Solution?Document3 pagesPlastic Waste Management: Is Circular Economy Really The Best Solution?MEnrique ForocaPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Proposal For Environmentally Friendly DiapersDocument9 pagesBusiness Proposal For Environmentally Friendly Diapersrorytan927322Pas encore d'évaluation

- Greening Bangladesh's Textile IndustryDocument11 pagesGreening Bangladesh's Textile IndustryGizele RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Green Chemistry PrinciplesDocument16 pagesGreen Chemistry PrinciplesSUBHASISH DASHPas encore d'évaluation

- 10) Waste Recycling and ReuseDocument29 pages10) Waste Recycling and ReuseAnonymous pqSZK6Pas encore d'évaluation

- Green Chemistry PDF 2 Introduction 2012Document28 pagesGreen Chemistry PDF 2 Introduction 2012Ilie GeorgianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chemical IndustryDocument9 pagesChemical Industryapi-320290632Pas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Disasters and the Growth of RegulationsDocument44 pagesEnvironmental Disasters and the Growth of RegulationsAmann AwadPas encore d'évaluation

- The Complete Guide to Industrial EcologyDocument35 pagesThe Complete Guide to Industrial EcologyKim NichiPas encore d'évaluation

- Green chemistry principles in organic synthesis experimentsDocument12 pagesGreen chemistry principles in organic synthesis experimentsSaurav GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Recycling of Textile Materials - Bojana VoncinaDocument37 pagesRecycling of Textile Materials - Bojana VoncinaRobertoPas encore d'évaluation

- Reviewing Textile Wastewater Produced by Industries: Characteristics, Environmental Impacts, and Treatment StrategiesDocument21 pagesReviewing Textile Wastewater Produced by Industries: Characteristics, Environmental Impacts, and Treatment StrategiesSoro FrancisPas encore d'évaluation

- Green ChemistryDocument37 pagesGreen ChemistryDepun MohapatraPas encore d'évaluation

- Control of Exhaust With CatconDocument16 pagesControl of Exhaust With CatconitsmeadityaPas encore d'évaluation

- 4-Case StudyDocument8 pages4-Case StudymanojrnpPas encore d'évaluation

- Design For Reuse Integrating Upcycling IDocument13 pagesDesign For Reuse Integrating Upcycling IKARLA PAVELA AGUILAR DIAZPas encore d'évaluation

- Importance of Environmental Science in Textile IndustryDocument4 pagesImportance of Environmental Science in Textile IndustryWaqar Baloch100% (1)

- Fdocuments - in - A Use Based Approach To Decision and Policy Making Blue Planet II Coverage ofDocument93 pagesFdocuments - in - A Use Based Approach To Decision and Policy Making Blue Planet II Coverage ofYash JoglekarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture Notes - 15 PagesDocument15 pagesLecture Notes - 15 PagesÄhmèd ÃzàrPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gasification of Residual Plastics Derived From Municipal Recycling FacilitiesDocument11 pagesThe Gasification of Residual Plastics Derived From Municipal Recycling FacilitiesYeong Leong LimPas encore d'évaluation

- C CC CC C CCC C C CC CC CDocument4 pagesC CC CC C CCC C C CC CC CVinay Kumar DhimanPas encore d'évaluation

- RecyclingDocument14 pagesRecyclingAbhay S ZambarePas encore d'évaluation

- Polymers 11 00696Document19 pagesPolymers 11 00696LaLa HaPas encore d'évaluation

- Waste ManagementDocument13 pagesWaste ManagementMs RawatPas encore d'évaluation

- Optimizing bioethanol supply chainDocument5 pagesOptimizing bioethanol supply chainrizkaPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental Management: Ecological Innovations in OrganizationsDocument23 pagesEnvironmental Management: Ecological Innovations in OrganizationsvimalPas encore d'évaluation

- DSEU PUSA CAMPUS Environmental Studies ProjectDocument17 pagesDSEU PUSA CAMPUS Environmental Studies ProjectSanjeev KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Jurnal Green ChemistDocument4 pagesJurnal Green ChemistLaila Nurul QodryPas encore d'évaluation

- Toxic Textiles: Why Organic is BetterDocument3 pagesToxic Textiles: Why Organic is Betterpranav_btext475Pas encore d'évaluation

- Wastewater treatment methods for small businessesDocument2 pagesWastewater treatment methods for small businessesGian Jelo SallePas encore d'évaluation

- Unitex Artikel CO2 Dyeing PDFDocument7 pagesUnitex Artikel CO2 Dyeing PDFChaitanya M MundhePas encore d'évaluation

- DystarDocument3 pagesDystarAwais ImranPas encore d'évaluation

- World's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherDocument27 pagesWorld's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book Publisherdefender paintsPas encore d'évaluation

- CLEANER PRODUCTION IN THE TEXTILE INDUSTRYDocument16 pagesCLEANER PRODUCTION IN THE TEXTILE INDUSTRYNattaya PunrattanasinPas encore d'évaluation

- Artigo Cenibra Lodo Biológico 02 - 2021Document10 pagesArtigo Cenibra Lodo Biológico 02 - 2021Marcelo SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Green ChemistryDocument8 pagesGreen Chemistryyeni100% (1)

- Environmental Examination of Waste Plastic Recycling Industry 2014Document13 pagesEnvironmental Examination of Waste Plastic Recycling Industry 2014Anonymous U5tA6h100% (1)

- AssignDocument10 pagesAssignAsjad UllahPas encore d'évaluation

- New DOC DocumentDocument32 pagesNew DOC DocumentbahreabdellaPas encore d'évaluation

- B. Tech. Seminar Report: Recycling of PlasticsDocument31 pagesB. Tech. Seminar Report: Recycling of PlasticsAkhil KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Applied SciencesDocument13 pagesApplied SciencesShirley ramosPas encore d'évaluation

- Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Cotton and Other Natural Fibers For Textile ApplicationsDocument9 pagesComparative Life Cycle Assessment of Cotton and Other Natural Fibers For Textile ApplicationsMarc AbellaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Lumber ProductsDocument105 pagesThe Lumber ProductsDemo DrogbaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bioplastic Wastes: The Best Final Disposition For Energy SavingDocument8 pagesBioplastic Wastes: The Best Final Disposition For Energy SavingShanaiah Charice GanasPas encore d'évaluation

- Human Perceptions of Recycled Textiles and Circular Fashion: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument28 pagesHuman Perceptions of Recycled Textiles and Circular Fashion: A Systematic Literature ReviewREJA PUTRA SIRINGORINGOPas encore d'évaluation

- Haode Evaluating The Life-Cycle Environmental ImpaDocument10 pagesHaode Evaluating The Life-Cycle Environmental ImpaAngga Eka WijayaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter OneDocument46 pagesChapter OneibukunadedayoPas encore d'évaluation

- Soild Waste Management Q and ADocument19 pagesSoild Waste Management Q and AHamed FaragPas encore d'évaluation

- Why Sustainability is Important for the Fashion IndustryDocument23 pagesWhy Sustainability is Important for the Fashion IndustryVishal kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- ResiduosDocument6 pagesResiduosAngelica ValarezoPas encore d'évaluation

- Green Chemistry for Dyes Removal from Waste Water: Research Trends and ApplicationsD'EverandGreen Chemistry for Dyes Removal from Waste Water: Research Trends and ApplicationsPas encore d'évaluation

- PTAS-11 Stump - All About Learning CurvesDocument43 pagesPTAS-11 Stump - All About Learning CurvesinSowaePas encore d'évaluation

- People vs. Ulip, G.R. No. L-3455Document1 pagePeople vs. Ulip, G.R. No. L-3455Grace GomezPas encore d'évaluation

- Department of Ece Vjec 1Document29 pagesDepartment of Ece Vjec 1Surangma ParasharPas encore d'évaluation

- 21st Century LiteraciesDocument27 pages21st Century LiteraciesYuki SeishiroPas encore d'évaluation

- Beams On Elastic Foundations TheoryDocument15 pagesBeams On Elastic Foundations TheoryCharl de Reuck100% (1)

- Understanding CTS Log MessagesDocument63 pagesUnderstanding CTS Log MessagesStudentPas encore d'évaluation

- Individual Differences: Mental Ability, Personality and DemographicsDocument22 pagesIndividual Differences: Mental Ability, Personality and DemographicsAlera Kim100% (2)

- 28 Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) vs. Velasco, 834 SCRA 409, G.R. No. 196564 August 7, 2017Document26 pages28 Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) vs. Velasco, 834 SCRA 409, G.R. No. 196564 August 7, 2017ekangPas encore d'évaluation

- Software EngineeringDocument3 pagesSoftware EngineeringImtiyaz BashaPas encore d'évaluation

- Resume Ajeet KumarDocument2 pagesResume Ajeet KumarEr Suraj KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Milwaukee 4203 838a PB CatalogaciónDocument2 pagesMilwaukee 4203 838a PB CatalogaciónJuan carlosPas encore d'évaluation

- Sample Property Management AgreementDocument13 pagesSample Property Management AgreementSarah TPas encore d'évaluation

- L-1 Linear Algebra Howard Anton Lectures Slides For StudentDocument19 pagesL-1 Linear Algebra Howard Anton Lectures Slides For StudentHasnain AbbasiPas encore d'évaluation

- HI - 93703 Manual TurbidimetroDocument13 pagesHI - 93703 Manual Turbidimetrojesica31Pas encore d'évaluation

- Project The Ant Ranch Ponzi Scheme JDDocument7 pagesProject The Ant Ranch Ponzi Scheme JDmorraz360Pas encore d'évaluation

- Department Order No 05-92Document3 pagesDepartment Order No 05-92NinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Question Paper Code: 31364Document3 pagesQuestion Paper Code: 31364vinovictory8571Pas encore d'évaluation

- Gerhard Budin PublicationsDocument11 pagesGerhard Budin Publicationshnbc010Pas encore d'évaluation

- Database Chapter 11 MCQs and True/FalseDocument2 pagesDatabase Chapter 11 MCQs and True/FalseGauravPas encore d'évaluation

- Top 35 Brokerage Firms in PakistanDocument11 pagesTop 35 Brokerage Firms in PakistannasiralisauPas encore d'évaluation

- Haul Cables and Care For InfrastructureDocument11 pagesHaul Cables and Care For InfrastructureSathiyaseelan VelayuthamPas encore d'évaluation

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument30 pagesSupply Chain ManagementSanchit SinghalPas encore d'évaluation

- 1LE1503-2AA43-4AA4 Datasheet enDocument1 page1LE1503-2AA43-4AA4 Datasheet enAndrei LupuPas encore d'évaluation

- Fundamental of Investment Unit 5Document8 pagesFundamental of Investment Unit 5commers bengali ajPas encore d'évaluation

- Ayushman BharatDocument20 pagesAyushman BharatPRAGATI RAIPas encore d'évaluation

- Dwnload Full International Monetary Financial Economics 1st Edition Daniels Solutions Manual PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full International Monetary Financial Economics 1st Edition Daniels Solutions Manual PDFelegiastepauleturc7u100% (16)

- Circular 09/2014 (ISM) : SubjectDocument7 pagesCircular 09/2014 (ISM) : SubjectDenise AhrendPas encore d'évaluation

- iec-60896-112002-8582Document3 pagesiec-60896-112002-8582tamjid.kabir89Pas encore d'évaluation