Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Patient Empowerment

Transféré par

Lindy Shane BoncalesDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

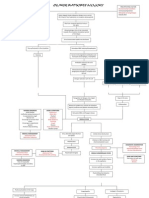

Patient Empowerment

Transféré par

Lindy Shane BoncalesDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Patient Education and Counseling 57 (2005) 153157 www.elsevier.

com/locate/pateducou

Review

Patient empowerment: reections on the challenge of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm

Robert M. Anderson*, Martha M. Funnell

Department of Medical Education, The Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center, The University of Michigan Medical School, 1500 E. Medical Ctr. Dr., 0201 Towsley Center, Room G-1111, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0201, USA Received 13 October 2003; received in revised form 3 April 2004; accepted 17 May 2004

Abstract Diabetes is a self-managed illness in which the decisions most affecting the health and well being of patients are made by the patients themselves. Many of these decisions involve routine activities of daily living (e.g., nutrition, physical activity). Effective diabetes care requires patients and health care professionals to collaborate in the development of self-management plans that integrate the clinical expertise of health care professionals with the concerns, priorities and resources of the patient. Collaborative diabetes care requires a new empowerment paradigm that involves a fundamental redenition of roles and relationships of health care professionals and patients. The challenges of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm differ substantially from those associated with the introduction of new technology. Those challenges are discussed in this paper. 2004 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Diabetes care; Collaborative care; Patient empowerment; Paradigms

1. Introduction Thomas Kuhn popularized the term paradigm in his classic work The Structure of Scientic Revolutions [1]. Kuhn denes a paradigm as a worldview that is essentially an interrelated collection of beliefs shared by scientists (for our purposes, health care professionals), i.e., a set of agreements about how problems are to be understood. Kuhn recognized that the way problems are dened, in large part, determines the nature of the strategies designed to solve them. In that work, Kuhn offered several insights into the nature of paradigms. For example, Kuhn noted that: 1. The underlying beliefs of the current or dominant paradigm form the epistemological foundation of professional education. 2. The beliefs learned during professional education exert a deep hold on the students mind.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 734 763 1153; fax: +1 734 936 1641. E-mail address: boba@umich.edu (R.M. Anderson).

3. New paradigms are strongly resisted by the professional community. 4. A paradigm shift resembles a Gestalt shift, a perceptual transformation. This essay is based on our insights and experiences over the last 16 years while introducing and promoting the patient empowerment approach to diabetes care. It represents knowledge acquired phenomenologically, rather than empirically, which is consistent with Kuhns assertion (#4 above) that paradigm shifts occur as Ah ha! moments rather than through logic or empirical study. Our experience is limited to care of diabetes, and we will conne our discussion to that experience, although we believe that the issues and insights presented in this paper apply to a variety of chronic diseases. During our 20 years on the faculty of medical and nursing schools, we have observed that health care professionals are socialized to a paradigm (Kuhn #1 above) derived from the treatment of acute illnesses [2,3]. In the acute-care system, patients surrender varying amounts of control to health care

0738-3991/$ see front matter 2004 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.05.008

154

R.M. Anderson, M.M. Funnell / Patient Education and Counseling 57 (2005) 153157

professionals in order to gain the expertise, technology, and compassion available from health care professionals. In this acute-care paradigm, health care providers take responsibility for solving their patients problems. This feeling of responsibility leaves many health care professionals feeling frustrated when their patients with diabetes do not follow their self-care recommendations. More than 25 years of behavioral research in diabetes resulting in hundreds of published studies focusing on the problem of noncompliance/non-adherence have failed to solve the problem [4]. A cursory Medline search produced over 1450 citations addressing the issue of noncompliance in diabetes, reecting a continuing search for new knowledge and strategies that will solve the problem of patient noncompliance. Although the issue of patient noncompliance has been addressed frequently, the assumptions embedded in the traditional approach (the acute-care paradigm) have seldom been called into question [5,6] (Kuhn #3 above). Attempts to address noncompliance assume that: 1. noncompliance is a valid and useful construct for understanding the behavior of patients, 2. the patient is the source of the problem, and 3. the solution to the problem of noncompliance is for patients to defer to the expertise (and authority derived from it) of health care professionals and follow the recommendations they have been given to change their behavior. Viewing diabetes care and education as an effort to improve compliance, i.e., persuading patients to comply with the recommendations of health care professionals, often fosters conict and tension [710]. Patients often feel judged and blamed for not following the advice given by health care professionals, even when that advice involves lifestyle changes that are very difcult to implement and sustain [810]. It has become increasingly evident that the acute-care paradigm does not work for the majority of patients with diabetes because its underlying assumptions do not t the facts of diabetes self-management. Treating diabetes within the acute-care paradigm can make problems worse rather than better because in their efforts to control the patients diabetes, many health care professionals are perceived by patients as trying to control their lives [11]. These attempts at control are often felt as criticism and/or an encroachment on the patients personal autonomy. For many patients noncompliance is an attempt to maintain and reafrm control over their own lives. Ironically, patients can harm themselves physically in order to protect themselves psychologically [7]. Others and we have advocated the adoption of a new paradigm that is based on the fundamental differences between the treatment of a self-managed chronic illness such as diabetes and the treatment of acute illnesses [1235]. People with diabetes provide the great majority of their health care themselves, much of which is interwoven into the

fabric of their daily lives. Diabetes self-management calls for a collaborative approach in which health care professionals and patients evaluate self-management decisions in terms of how well they are helping patients to achieve their own health care goals [1235].

2. Barriers to the adoption of the empowerment paradigm We have learned that recognizing the need for a new empowerment paradigm is only the rst step on the long journey to its adoption. Below is a description of some of the barriers to the adoption of the empowerment paradigm in diabetes that we have experienced over the course of our work. 2.1. Old paradigms trump new techniques For many years we have written books and articles [12 19,3235] in an attempt to elucidate empowerment as a paradigm, i.e., a philosophy or overall approach [13] to diabetes care. Over time an increasing number of health care professionals, especially diabetes educators, became interested in the empowerment philosophy and the data supporting its utility [36]. It became clear to us that these health care professionals needed a way to operationalize the empowerment paradigm with individual patients. In response to this need, we adapted a person-centered approach from counseling psychology [3741] to the needs and realities of diabetes education. We then developed a 3-day training program [42] to provide educators with a set of skills and strategies that were consistent with the empowerment paradigm and were well suited to diabetes care and education. During the training programs, educators practiced the empowermentcounseling model and reviewed videotapes of their practice sessions. While reviewing the videotapes of practice sessions, we realized that although most of the educators agreed with the empowerment approach intellectually, they had not changed their underlying behavior inherent to the acute-care paradigm, i.e., they still felt responsible for getting patients to follow the recommendations they had been given by their physician. The educators had taken a step-by-step empowerment-based approach to facilitating self-directed behavior change and converted it (unconsciously) into a technique for improving patient compliance. The traditional acute-care paradigm had such a deep hold (Kuhn #2 above) that they applied it almost instinctively. This observation provided one of our most important insights about the relationship between paradigms to practice, i.e., no matter what educational/counseling technique is used; it becomes an expression of the health care professionals underlying philosophy of care. We have encountered many practical health care professionals who believe that a paradigm or philosophy of care is abstract

R.M. Anderson, M.M. Funnell / Patient Education and Counseling 57 (2005) 153157

155

and therefore largely irrelevant. Our experience indicates that quite the opposite is true. 2.2. Paradigms are powerful but often invisible One of the most challenging aspects of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm is that the paradigms learned by health care professionals during their training exert a strong inuence on how they interact with patients. Yet, for many of them their paradigm (and its inuence) is so embedded in their consciousness that they are unaware of its existence. They do not realize that they were socialized to a paradigm during their professional education, i.e., they adopted the worldview of their mentors and role models without understanding a paradigm is one view of reality not reality itself (Kuhn #2 above). They learned what it means to be a health care professional without ever considering the fact that alternative denitions for the roles and responsibilities of health care professionals can and do exist. Their paradigm becomes part of their professional (and often personal) identity. Once in practice they do not see their paradigm at work but rather see their work through the paradigm. Once adopted, a paradigm can have such a deep hold (Kuhn #2 above) on us that it acts like a psychological eye with which we see the world but which we cannot see. For example, after giving a presentation about empowerment, it is not uncommon for a health care professional in the audience to ask but will it improve patient compliance? The acute-care paradigm is not only embedded in the minds of individual health care professionals, but is also the basis for most of the policies and procedures of health care organizations and third-party payers: for example, reimbursement for care is based on the treatment of acute conditions and often does not cover services necessary for effective diabetes care such as dietary counseling. 2.3. Paradigm shifts can take a generation Even today medical schools continue to socialize physicians to the acute-illness approach to care [2,3] (Kuhn #1 above). Although some physicians and health care systems have changed, most have not. The rate of change may increase as more health care professionals and researchers recognize the need for a fundamentally different approach to the care of diabetes and other chronic illnesses [43]. Nonetheless, the process will take longer than the introduction of a new drug or technical innovation. We have encountered a number of health care professionals who are employing a collaborative approach to diabetes care but are frustrated by a lack of support from their colleagues and/or health care systems. This makes their work more challenging because while the adoption of a new empowerment paradigm takes time, the frustrations they feel in trying to provide collaborative diabetes care in a context dominated by the acutecare paradigm are immediate and tangible.

2.4. Empowerment as politically correct (PC) We have encountered health care professionals who are skeptical about the empowerment approach to care because they view it as the latest politically correct terminology and/or a sociopolitical effort to wrest the control of diabetes care from physicians and other health care professionals. This view is incorrect. The empowerment approach simply recognizes that patients are already in control of the most important diabetes management decisions. Even though these facts are virtually self-evident they go unseen because of the deep hold of the acute-care paradigm. When we acknowledge that the control of diabetes self-management rests with the patient, it follows logically that the responsibility for making self-management decisions and living with their consequences rests with our patients as well. When we rst began presenting the empowerment approach to collaborative diabetes care, it was not uncommon for health care professionals to say to us Youre asking us to give up control. The illusion that health care professionals control diabetes care derives from looking at the facts of diabetes self-management through the lens of the acute-care paradigm. The persistence of this illusion is testimony to the power of paradigms. The empowerment approach requires a change from feeling responsible for patients to feeling responsible to patients. This means acting as collaborators who provide patients with the information, expertise and support to make the best possible diabetes self-management decisions based on the patients own health priorities and goals. This view of diabetes self-management is based on the reality of diabetes self-management, not on a sociopolitical agenda for change. Nonetheless, in our experience the patient empowerment paradigm is often perceived as an assault on deeply imbedded professional roles and responsibilities (Kuhn #3 above). 2.5. The medical industrial model Health care professionals are under increasing pressure to become more efcient [44]. The physicians, nurses, and dietitians with whom we interact on a daily basis tell us that they are being asked to see more patients in less time, practice evidence-based medicine and evaluate measurable health outcomes. Consequently, many health care professionals are concerned that shifting to an empowerment paradigm will take too much time. Thus, it is critical to demonstrate through research that patient-centered, relationship-oriented, collaborative care can improve outcomes without signicantly extending the time required for patient visits [45]. We have and will continue to develop interventions based on patient empowerment whose impact can be scientically evaluated in terms of measurable outcomes [36,42,46]. However, these efforts in and of themselves cannot provide an evaluation of the underlying empowerment paradigm because a paradigm is a worldview or philosophy of

156

R.M. Anderson, M.M. Funnell / Patient Education and Counseling 57 (2005) 153157

care and cannot be evaluated scientically. While programs and strategies arising from a paradigm can and should be evaluated, we should note that valuing only the tangible, measurable products of medicine could contribute to a dehumanization of the health care system, which can ultimately fail to nurture either patients or health care professionals.

3. Conclusion 3.1. Reective practice We encourage health care professionals to reect on their experience with the assumptions underlying the acute-care paradigm when applied to diabetes. Such reection can create the psychological space necessary for the adoption of a new paradigm truly appropriate to the reality of diabetes care. A useful way to actually see the existing acute-care paradigm is to employ a psychological mirror, i.e., to reect on care behavior in an attempt to understand our paradigm/philosophy of care and the ways in which it shapes our interactions with patients. Those interested in this process could answer the following questions: 1. Do I have the right to expect my patients to defer to my judgment about how they conduct their daily lives to manage their diabetes? 2. Do I feel responsible for my patients level of blood glucose control? 3. Do I nd myself trying to persuade my patients to follow my advice? 4. Do I feel frustrated if my patients do not follow my recommendations? 5. Do I feel like my noncompliant patients are undermining my effectiveness? In our experience such reective practice can and has led to paradigm shifts. Fostering the kind of discourse among our colleagues that subjects the assumptions embedded in the acute-care paradigm to critical examination is an available and potentially potent method to stimulate the kind of perceptual shift (Kuhn #4 above) that results in the adoption of a new paradigm. 3.2. Taking responsibility We believe that health care professionals who agree with and value the empowerment paradigm have a responsibility to become advocates for patient-centered collaborative diabetes care. This often means addressing resistance from supervisors and systems wedded to the acute-care model. No single one of us can bring about a paradigm shift, but we can accept responsibility for working toward that end. Trying to provide diabetes care in an acute-care paradigm diminishes the adequacy of the care being received by patients. Because

it is an attempt to do the impossible, i.e., be responsible for what is not in our control, the acute-care approach frustrates and limits the effectiveness of health care professionals as well. Seeing the futility of applying the acute-care approach to diabetes care liberates the health care professional to consider the adoption of an empowerment paradigm that is grounded in the reality of diabetes self-management. It has been our experience that the adoption of the collaborative care approach to diabetes self-management empowers heath care professionals as much as it does patients.

References

[1] Kuhn TS. The structure of scientic revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1970. [2] Assal JP. Revisiting the approach to treatment of long-term illness: from the acute to the chronic state. A need for educational and managerial skills for long-term follow-up. Patient Educ Couns 1999;37:99111. [3] Nair BR, Finucane PM. Reforming medical education to enhance the management of chronic disease. Med J Aust 2003;179:2579. [4] Lutfey KE, Wishner WJ. Beyond compliance is adherence. Diabetes Care 1999;22:6359. [5] Funnell MM, Anderson RM. The problem with compliance in diabetes. JAMA 2000;284:1709. [6] Anderson RM. Is the problem of noncompliance all in our heads? Diabetes Educator 1985;11:314. [7] Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Compliance and adherence are dysfunctional concepts in diabetes care. Diabetes Educator 2000;26:597 604. [8] Trecroci D. Who are you calling noncompliant? Diabetes Interview 1999;8:203. [9] Hoover J. Compliance from a patients perspective. Diabetes Educator 1980;6:212. [10] King SM. Dont call me noncompliant. Diabetes Interview 1999;88:3. [11] Anderson RM. Patient empowerment and the traditional medical model: a case of irreconcilable differences? Diabetes Care 1995;18: 4125. [12] Funnell MM, Anderson RM, Arnold MS, Barr PA, Donnelly M, Johnson PD, Taylor-Moon D, White NH. Empowerment: an idea whose time has come in diabetes education. Diabetes Educator 1991;17:3741. [13] Anderson RM, Funnel MM. Theory is the cart, vision is the horse: reections on research in diabetes patient education. AADE Res Summit Suppl Diabetes Educator 1999;S4351. [14] Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Arnold MS. Beyond compliance and glucose control: educating for patient empowerment. In: Rifkin H, Colwell JA, Taylor SI, editors. Diabetes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1991. p. 12859. [15] Vazquez EF, Anderson RM. Activaction y motivacion del paciente diabetico. In: Islas S, Lifshitz A, editors. Diabetes mellitus 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Interamericana: Mexico; 1999. p. 36580. [16] Anderson RM, Funnel MM, Carlson A, Saleh-Stattin N, Cradock S, Skinner TC. Facilitating self-care through empowerment. In: Snoek FJ, Skinner TC, editors. Psychology in diabetes care. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. p. 6997. [17] Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Working toward the next generation of diabetes self-management education. Am J Prev Med 2002;22:35. [18] Rubin RR, Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Collaborative diabetes care. Pract Diabetol 2002;21:2932. [19] Glasgow RE, Anderson RM. In diabetes care, moving from compliance to adherence is not enough: something entirely different is needed. Diabetes Care 1999;22:20902.

R.M. Anderson, M.M. Funnell / Patient Education and Counseling 57 (2005) 153157 [20] Fisher Jr EB, Heins JM, Hiss RG, Lorenz RA, Marrero DG, McNabb WL, Wylie-Rosett J. Metabolic control matters: nationwide translation of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial: analysis and recommendations. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1993. [21] McCulloch DK, Glasgow RE, Hampson SE, Wagner E. A systematic approach to diabetes management in the post-DCCT era. Diabetes Care 1994;17:7659. [22] McCulloch DK, Price MJ, Hindmarsh M, Wagner EH. A populationbased approach to diabetes management in a primary care setting: early results and lessons learned. Eff Clin Pract 1998;1:1222. [23] Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer JK, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1097102. [24] Wagner EH. Population-based management of diabetes care. Patient Educ Couns 1995;26:22530. [25] Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996;74:51144. [26] Etzwiler DD. Chronic care: a need in search of a system. Diabetes Educator 1997;23:56973. [27] Byers JF. Holistic acute care units: partnerships to meet the needs of the chronically ill and their families. AACN Clin Issues 1997;8: 271279. [28] Mur-Veeman I, Eijkelberg I, Spreeuwenberg C. How to manage the implementation of shared care: a discussion of the role of power, culture and structure in the development of shared care arrangements. J Manage Med 2001;15:14255. [29] Sullivan M. The new subjective medicine: taking the patients point of view on health care. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:1595604. [30] van Eijk JT, de Haan M. Care for the chronically ill: the future role of health care professionals and their patients. Patient Educ Couns 1998;35:23340. [31] Wilson PM. The expert patient: issues and implications for community nurses. Br J Commun Nurs 2002;7:5149. [32] Anderson RM, Funnell MM. The art of empowerment: stories and strategies for diabetes educators. Alexandria, VA: American Diabetes Association; 2000.

157

[33] Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Burkhart NT, Gillard ML, Nwankwo RB. 101 tips for behavior change in diabetes education. Alexandria, VA: American Diabetes Association; 2002. [34] Funnell MM, Anderson RM, Burkhart NT, Gillard ML, Nwankwo RB. 101 tips for diabetes self-management education. Alexandria, VA: American Diabetes Association; 2002. [35] Anderson RM, Pibernik-Okanovic M. The patient empowerment approach to diabetes care. Diabetol Croatica 1999;28:10111. [36] Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Butler PM, Arnold MS, Fitzgerald JT, Feste CC. Patient empowerment: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 1995;18:9439. [37] Rogers C. Freedom to learn for the 80s. Columbus, OH: Merril; 1983. [38] Rogers C. Client-centered therapy. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifin; 1965. [39] Combs A, Avila D, Purkey W. Helping relationships. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1978. [40] Combs A. A personal approach to teaching: beliefs that make a difference. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1982. [41] Carkhuff R. The art of helping. Amherst, MA: Human Resource Dev. Press; 1975. [42] Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Barr PA, Dedrick RF, Davis WK. Learning to empower patients: results of professional education program for diabetes educators. Diabetes Care 1991;14:58490. [43] Glasgow RE, Hiss RG, Anderson RM, Friedman NM, Hayward RA, Marrero DG, Taylor CB, Vinicor F. Report of the Health Care Delivery Work Group: behavioral research related to the establishment of a chronic disease model for diabetes care. Diabetes Care 2001;24:12430. [44] Frohna JG, Frohna A, Gahagan S, Anderson RM. Tips for communicating with patients in managed care. Semin Med Pract 2001;4:29 36. [45] Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA 2000;284:10217. [46] Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Fitzgerald JT, Marrero DG. The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: a measure of psychosocial self-efcacy. Diabetes Care 2000;23:73943.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Public Health Approach To Diabetes.14Document4 pagesThe Public Health Approach To Diabetes.14Lindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Press FinalDocument137 pagesCase Press FinalLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Elementary Library OrientationDocument20 pagesElementary Library OrientationLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Western Union Pay FormDocument2 pagesWestern Union Pay FormLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Press Cover PageDocument4 pagesCase Press Cover PageLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Epinephrine Classifications: Therapeutic: Antiasthmatics, Bronchodilators, Vasopressors Pharmacologic: Adrenergics IndicationsDocument14 pagesEpinephrine Classifications: Therapeutic: Antiasthmatics, Bronchodilators, Vasopressors Pharmacologic: Adrenergics IndicationsLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Press AriDocument35 pagesCase Press AriLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Press Cover PageDocument4 pagesCase Press Cover PageLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Community Health NursingDocument6 pagesCommunity Health NursingLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Final PurpuraDocument94 pagesFinal PurpuraLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- 000000Document7 pages000000Lindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Patho Explanation in MSDocument1 pagePatho Explanation in MSLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- SuturesDocument5 pagesSuturesLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- SuturesDocument5 pagesSuturesLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Patho DengueDocument3 pagesPatho DengueLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- 18Document4 pages18Lindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- NCP Copd-AscitesDocument4 pagesNCP Copd-AscitesLindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Pa Tho Physiology of Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 and 2Document3 pagesPa Tho Physiology of Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 and 2Lindy Shane BoncalesPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- MODULE CONTENT P3 in PE1Document10 pagesMODULE CONTENT P3 in PE1Florrie Jhune BuhawePas encore d'évaluation

- Book Review On The Saint The Surfer and The CeoDocument9 pagesBook Review On The Saint The Surfer and The CeoDhrumit PatelPas encore d'évaluation

- Focus3 2E Unit Test Dictation Listening Reading Unit4 GroupADocument3 pagesFocus3 2E Unit Test Dictation Listening Reading Unit4 GroupAI Gusti Putu Cahya Arsya P.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Emi Wong WorkoutDocument1 pageEmi Wong WorkoutNoviana MithaPas encore d'évaluation

- At The Gym: Lingua House Lingua HouseDocument4 pagesAt The Gym: Lingua House Lingua HousediogofffPas encore d'évaluation

- Hope 3 - Q1 - DW4 2Document3 pagesHope 3 - Q1 - DW4 2JORDAN SANTOSPas encore d'évaluation

- Complete 1 PDFDocument227 pagesComplete 1 PDFjayantiPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexander J.A Cortes - The AJAC Diet by Alexander Cortes-Gumroad (2020)Document35 pagesAlexander J.A Cortes - The AJAC Diet by Alexander Cortes-Gumroad (2020)Ammar BasharatPas encore d'évaluation

- Tested Lifters 2019 2020 02 11Document6 pagesTested Lifters 2019 2020 02 11GustavoPas encore d'évaluation

- Muhaimin 12th To 15th February, 23Document4 pagesMuhaimin 12th To 15th February, 23Muhaimin EshmumPas encore d'évaluation

- Blood Sugar Premier Is A Supplement Made Up of PureDocument7 pagesBlood Sugar Premier Is A Supplement Made Up of PureNayab NazarPas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 6 - Training The Cardiorespiratory System (Compatibility Mode)Document6 pagesTopic 6 - Training The Cardiorespiratory System (Compatibility Mode)JohannaMaizunPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus at Fundamentals of EnglishDocument11 pagesSyllabus at Fundamentals of EnglishMaria Garcia Pimentel Vanguardia IIPas encore d'évaluation

- Environmental TheoryDocument3 pagesEnvironmental TheoryLucilyn Mae CubilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Semana 15 Unity Elite ProgramDocument6 pagesSemana 15 Unity Elite ProgramEdinson Jhair Mantilla RomeroPas encore d'évaluation

- HIIT 29.10 and 31.10 Dan John Barbell ComplexDocument7 pagesHIIT 29.10 and 31.10 Dan John Barbell ComplexGuillaume VingtcentPas encore d'évaluation

- Perks of Eating VegetablesDocument1 pagePerks of Eating VegetablesChayne Althea RequinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Weight Training Unit PlanDocument31 pagesWeight Training Unit PlanBill WaltonPas encore d'évaluation

- Lena-Snow Summer ChallengeDocument7 pagesLena-Snow Summer ChallengeBrionna BockPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 National Standards For Diabetes Self-Management Education and SupportDocument16 pages2017 National Standards For Diabetes Self-Management Education and SupportMellan Apriiaty SimbolonPas encore d'évaluation

- Module Two Wellness PlanDocument15 pagesModule Two Wellness PlanIsuodEditsPas encore d'évaluation

- Mindful Eating and Common Diet Programs Lower Body WeightDocument9 pagesMindful Eating and Common Diet Programs Lower Body WeightJuliana MontovaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Rodent Baits Activity Trend Analysis Jan-MarDocument37 pagesRodent Baits Activity Trend Analysis Jan-MarblackicemanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Deisel Strength Mass ReportDocument45 pagesThe Deisel Strength Mass ReportNic Prince91% (11)

- Circuit Training FormDocument1 pageCircuit Training FormjonathanPas encore d'évaluation

- Fat Loss Plan - Week 1Document2 pagesFat Loss Plan - Week 1John RohrerPas encore d'évaluation

- Health Assessment Chapter 13Document6 pagesHealth Assessment Chapter 13Shade ElugbajuPas encore d'évaluation

- 2 - Atp (Shalin) - 102042Document9 pages2 - Atp (Shalin) - 102042selva santosgonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- WSM Final WorkbookDocument198 pagesWSM Final WorkbookAS3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Kettlebell Only 1Document14 pagesKettlebell Only 1areo.barPas encore d'évaluation