Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Gastrointestinal Bleeding Is Bleeding That Occurs Anywhere in The Digestive Tract

Transféré par

April Joy RutaquioDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gastrointestinal Bleeding Is Bleeding That Occurs Anywhere in The Digestive Tract

Transféré par

April Joy RutaquioDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Gastrointestinal bleeding is bleeding that occurs anywhere in the digestive tract, also called the gastrointestinal tract, which

runs from the mouth to the anus. Blood may be present in vomit or stool. Depending on where the bleeding originates, the blood may be visible or occult, which means that it can be detected only by laboratory testing. The severity of gastrointestinal bleeding varies among individuals depending on the cause. Lower GI bleeding Source in the small intestine or colon (below the ligament of Treitz)

under age 50. Colitis (from ischemic, postradiation, or infectious causes) and polyps or malignancies each account for approximately 18% of lower GI bleeds. Common causes of gastrointestinal bleeding are inflammation and infections in the digestive tract, such as gastritis. Mild gastrointestinal bleeding is common with viral infections, and this bleeding will go away as the infection resolves. People with an anal fissure or hemorrhoids may also have mild bleeding that resolves on its own. If severe bleeding occurs, it can result in significant blood loss, leading to symptoms such as lightheadedness, dizziness, fainting, or difficulty breathing. Angiodysplasia (abnormalities in the intestinal blood vessels) Bleeding disorders, such as hemophilia or von Willebrands disease Bleeding diverticulum (pouch formed by weakening in the intestinal wall) Celiac disease (severe sensitivity to gluten from wheat and other grains that causes intestinal damage) Dysentery (infectious inflammation of the colon causing severe bloody diarrhea) Inflammatory bowel disease (includes Crohns disease and ulcerative colitis) Medication effects (caused by medications such as warfarin, clopidogrel) Hematemesis is vomiting of red blood and indicates upper GI bleeding, usually from an arterial source or varix. Coffee-ground emesis is vomiting of dark brown, granular material that resembles coffee grounds. It results from upper GI bleeding that has slowed or stopped, with conversion of red Hb to brown hematin by gastric acid. Hematochezia is the passage of gross blood from the rectum and usually indicates lower GI bleeding but may result from vigorous upper GI bleeding with rapid transit of blood through the intestines. Melena is black, tarry stool and typically indicates upper GI bleeding, but bleeding from a source in the small bowel or right colon may also be the cause. About 100 to 200 mL of blood in the upper GI tract is required to cause melena, which may persist for several days after bleeding has ceased. Black stool that does not contain occult

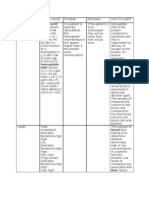

RISK FACTORS Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common problem that carries a mortality rate of 5% to 10%, depending on the site, severity, etiology, and underlying risk factors. That mortality rate has not changed over the past 50 years, despite diagnostic and therapeutic advances. In general, GI bleeding is twice as common in males, and the incidence increases with age. Evaluation of GI bleeding involves assessing hemodynamic stability, resuscitating the patient as needed, locating the source of the bleed, and treating the underlying cause. Several predisposing factors have been identified, including a history of a GI bleed and the use of aspirin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, anticoagulants, alcohol, and cigarettes. Alterations of the GI mucosa, such as in esophagitis, gastric or duodenal ulcers, polyps, diverticuli, inflammatory bowel disease, colitis, and prior intestinal anastomosing surgeries, must also be considered. Additional risk factors include vascular abnormalities, such as esophageal, gastric, and intestinal varices seen in cirrhosis, and hemorrhoids, angiodysplasia, and other vascular malformations such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias. Coagulopathies, anal fissures, and GI malignancies may also predispose to GI bleeding. ETIOLOGY OR CAUSE Lower GI bleeds, by anatomic definition, originate distal to the ligament of Treitz. Diverticulitis and angiodysplasia, which account for 30% and 8% of lower GI bleeds, respectively, are more prevalent in patients over age 65, whereas hemorrhoidal bleeding (5% of lower GI bleeds) is more common in patients

blood may result from ingestion of iron, bismuth, or various foods and should not be mistaken for melena. Chronic occult bleeding can occur from anywhere in the GI tract and is detectable by chemical testing of a stool specimen. Acute, severe bleeding also can occur from anywhere in the GI tract. Patients may present with signs of shock. Those with underlying ischemic heart disease may develop angina or MI because of hypoperfusion.

Regardless of the source, the first and most important initial step in managing a GI bleed is assessing hemodynamic stability. Patients should be immediately evaluated for signs and symptoms of shock, and those without overt tachycardia or hypotension must be examined for orthostatic hemodynamic changes. Hemodynamic instability or evidence of significant ongoing blood loss (active hematemesis, melena, or moderate hematochezia) are indications for admission to a critical care unit for more intensive monitoring. Resuscitation in patients with GI bleeding includes placement of two large-bore (16- or 18-gauge) intravenous (IV) lines or a central venous line. Patients with hemodynamic compromise may require immediate volume expansion with blood transfusions and IV fluids. Vasopressors may be indicated in some patients if volume expansion alone does not stabilize their blood pressure. Pulse oximetry and an ECG may be indicated in patients with a history of pulmonary disease or coronary artery disease. While unstable patients may require an early blood transfusion, all patients with GI bleeds should be typed and cross-matched in case they need a transfusion. Initial laboratory tests include hemoglobin and hematocrit, platelets, clotting times, and electrolytes. Initial hemoglobin and hematocrit levels may not reflect the severity of GI bleeding; frequent monitoring may be necessary. Laser photocoagulation, bipolar electrocoagulation, and heater probe coagulation are often used in conjunction with injection therapy to maximize hemostasis. Capsule endoscopy may be utilized in the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, especially when the source is the small bowel. Angiography can help visualize GI bleeding but requires active blood loss at a rate of 1 ml/min in order to be effective. Hence, angiography is highly specific but variably sensitive. Like endoscopy, angiography has both diagnostic and therapeutic advantages; patients can undergo simultaneous identification and embolization of bleeding vessels. Radionucleotide scanning can detect slower bleeds (0.5 ml/min) and is less invasive and more sensitive than angiography. However, it is less specific than a positive endoscopic or angiographic finding. In general, for patients without contraindications to endoscopy, EGD or colonoscopy, or both, are preferred as first-line procedures over angiography and radionucleotide scanning. Patients who cannot be

GROSS OR ANATOMICAL PHYSICAL CHANGES Clinically significant bleeding leads to postural changes in heart rate or blood pressure, tachypnea, tachycardia, and recumbent hypotension.

Hemodynamic changes Orthostatic decrease in blood pressure > 10 mmHg usually indicates > 20% reduction in blood volume. Systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg usually indicates < 30% reduction in blood volume

Clinical manifestation of client Patients with lower GI bleeding may complain of hematochezia. Regardless of the FOBT result, a rectal exam is important to assess for the presence of hemorrhoids or anal fissures. Just as in upper GI bleeds, the rate of lower GI hemorrhaging determines the type and severity of symptoms on presentation. Abdominal pain, which may be the chief complaint in patients diagnosed with any type of GI bleed, is not always a reliable sign. The presence of abdominal pain does not necessarily imply a bleed is occurring (low specificity), nor does it accurately localize the site of the bleed. Similarly, the absence of pain does not exclude the possibility of a bleed (low sensitivity). On the other hand, peritoneal signs elicited on physical examination of patients with GI bleeding warrant early surgical consultation. Procedures done

stabilized by these procedures should undergo surgery to localize and control bleeding. Epigastric abdominal discomfort relieved by food or antacids suggests peptic ulcer disease. However, many patients with bleeding ulcers have no history of pain. Weight loss and anorexia, with or without a change in stool, suggest a GI cancer. A history of cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis suggests esophageal varices. Dysphagia suggests esophageal cancer or stricture. Vomiting and retching before the onset of bleeding suggests a Mallory-Weiss tear of the esophagus, although about 50% of patients with Mallory-Weiss tears do not have this history. A history of bleeding (eg, purpura, ecchymosis, hematuria) may indicate a bleeding diathesis (eg, hemophilia, hepatic failure). Bloody diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain suggest ischemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease (eg, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease), or an infectious colitis (eg, Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, amebiasis). Hematochezia suggests diverticulosis or angiodysplasia. Fresh blood only on toilet paper or the surface of formed stools suggests internal hemorrhoids or fissures, whereas blood mixed with the stool indicates a more proximal source. Occult blood in the stool may be the first sign of colon cancer or a polyp, particularly in patients > 45 yr. Blood in the nose or trickling down the pharynx suggests the nasopharynx as the source. Spider angiomas, hepatosplenomegaly, or ascites is consistent with chronic liver disease and hence possible esophageal varices. Arteriovenous malformations, especially of the mucous membranes, suggest hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Cutaneous nail bed and GI telangiectasia may indicate systemic sclerosis or mixed connective tissue disease. CBC should be obtained in patients with occult blood loss. Those with more significant bleeding also require coagulation studies (eg, platelet count, PT, PTT) and liver function tests (eg, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, AST, ALT). Type and crossmatch are done if bleeding is ongoing. Hb and Hct may be repeated up to every 6 h in patients with severe bleeding. Additionally, one or more diagnostic procedures are typically required. Nasogastric aspiration and lavage should be done in all patients with suspected upper GI bleeding (eg, hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, melena, massive

rectal bleeding). Bloody nasogastric aspirate indicates active upper GI bleeding, but about 10% of patients with upper GI bleeding have no blood in the nasogastric aspirate. Coffee-ground material indicates bleeding that is slow or stopped. If there is no sign of bleeding, and bile is returned, the NGT is removed; otherwise, it is left in place to monitor continuing or recurrent bleeding. Nonbloody, nonbilious return is considered a nondiagnostic aspirate. Upper endoscopy (examination of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum) should be done for upper GI bleeding. Because endoscopy may be therapeutic as well as diagnostic, it should be done rapidly for significant bleeding but may be deferred for 24 h if bleeding stops or is minimal. Upper GI barium x-rays have no role in acute bleeding, and the contrast used may obscure subsequent attempts at angiography. Angiography is useful in the diagnosis of upper GI bleeding and permits certain therapeutic maneuvers (eg, embolization, vasoconstrictor infusion). Flexible sigmoidoscopy and anoscopy may be all that is required acutely for patients with symptoms typical of hemorrhoidal bleeding. All other patients with hematochezia should have colonoscopy, which can be done electively after routine preparation unless there is significant ongoing bleeding. In such patients, a rapid prep (5 to 10 L of polyethylene glycol solution delivered via NGT or by mouth over 3 to 4 h) often allows adequate visualization. If colonoscopy cannot visualize the source and ongoing bleeding is sufficiently rapid (> 0.5 to 1 mL/min), angiography may localize the source. Some angiographers first take a radionuclide scan to focus the examination, because angiography is less sensitive than the radionuclide scan. Diagnosis of occult bleeding can be difficult, because heme-positive stools may result from bleeding anywhere in the GI tract. Endoscopy is the preferred method, with symptoms determining whether the upper or lower GI tract is examined first. Doublecontrast barium enema and sigmoidoscopy can be used for the lower tract when colonoscopy is unavailable or the patient refuses it. If the results of upper endoscopy and colonoscopy are negative and occult blood persists in the stool, an upper GI series with small-bowel follow-through, small-bowel endoscopy (enteroscopy), capsule endoscopy, technetium-labeled colloid or RBC scan, and angiography should be considered. Treatment

Secure airway if needed IV fluid resuscitation Blood transfusion if needed

platelets. Fresh frozen plasma should be transfused after every 4 units of packed RBCs.

In some, angiographic or endoscopic hemostasis (See also the American College of Gastroenterology's practice guidelines on management of the adult patient with acute lower GI bleeding.) Hematemesis, hematochezia, or melena should be considered an emergency. Admission to an ICU, with consultation by both a gastroenterologist and a surgeon, is recommended for all patients with severe GI bleeding. General treatment is directed at maintenance of the airway and restoration of circulating volume. Hemostasis and other treatment depend on the cause of the bleeding. Airway: A major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with active upper GI bleeding is aspiration of blood with subsequent respiratory compromise. To prevent these problems, endotracheal intubation should be considered in patients who have inadequate gag reflexes or are obtunded or unconscious particularly if they will be undergoing upper endoscopy. Fluid resuscitation: IV fluids are initiated as for any patient with hypovolemia or hemorrhagic shock (see Shock and Fluid Resuscitation: Intravenous Fluid Resuscitation): healthy adults are given normal saline IV in 500- to 1000-mL aliquots until signs of hypovolemia remitup to a maximum of 2 L (for children, 20 mL/kg, that may be repeated once). Patients requiring further resuscitation should receive transfusion with packed RBCs. Transfusions continue until intravascular volume is restored and then are given as needed to replace ongoing blood loss. Transfusions in older patients or those with coronary artery disease may be stopped when Hct is stable at 30 unless the patient is symptomatic. Younger patients or those with chronic bleeding are usually not transfused unless Hct is < 23 or they have symptoms such as dyspnea or coronary ischemia. Platelet count should be monitored closely; platelet transfusion may be required with severe bleeding. Patients who are taking antiplatelet drugs (eg, clopidogrel, aspirin) have platelet dysfunction, often resulting in increased bleeding. Platelet transfusion should be considered when patients taking these drugs have severe ongoing bleeding, although a residual circulating drug (particularly clopidogrel) may inactivate transfused

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Abnormal PregnancyDocument2 pagesAbnormal PregnancyApril Joy RutaquioPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Laboratory TestDocument4 pagesLaboratory TestApril Joy RutaquioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Uses of PartographDocument6 pagesUses of PartographApril Joy RutaquioPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- NCM ResearchDocument2 pagesNCM ResearchApril Joy RutaquioPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Corneal StainingDocument2 pagesCorneal StainingApril Joy RutaquioPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- What Is Gastrointestinal BleedingDocument8 pagesWhat Is Gastrointestinal BleedingApril Joy RutaquioPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- What Is Gastrointestinal BleedingDocument8 pagesWhat Is Gastrointestinal BleedingApril Joy RutaquioPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Ronald John Recio, M.A., Rpsy, Emdrprac. Mbpss Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG Maynila Puso MoDocument22 pagesRonald John Recio, M.A., Rpsy, Emdrprac. Mbpss Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG Maynila Puso MoChunelle Maria Victoria EspanolPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- CVS Embryology Questions and Study Guide - Quizlet Flashcards by Hugo - OxfordDocument5 pagesCVS Embryology Questions and Study Guide - Quizlet Flashcards by Hugo - OxfordAzizPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- I. Clinical Summary A. General Data ProfileDocument8 pagesI. Clinical Summary A. General Data ProfileDayan CabrigaPas encore d'évaluation

- SerotoninaDocument12 pagesSerotoninajodiePas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Animal's Circulartory System.Document2 pagesAnimal's Circulartory System.CHANON KIATKAWINWONGPas encore d'évaluation

- Critical Thinking Flowsheet For Nursing StudentsDocument3 pagesCritical Thinking Flowsheet For Nursing StudentssparticuslivesPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- SepsisDocument19 pagesSepsisapi-308355800Pas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Stomatitis: An Overview: Protecting The Oral Cavity During Cancer TreatmentDocument4 pagesStomatitis: An Overview: Protecting The Oral Cavity During Cancer TreatmentLenna IkawatiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Shadow SlaveDocument2 988 pagesShadow Slaveingrid ruvinga100% (3)

- Lung Structure - BioNinjaDocument2 pagesLung Structure - BioNinjaDaniel WalshPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- 23312-02 - Dissertation ETH Zürich Michael EderDocument108 pages23312-02 - Dissertation ETH Zürich Michael EderMichael EderPas encore d'évaluation

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Biol1300.001.09f Taught by Ilya Sapozhnikov (Isapoz)Document13 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Biol1300.001.09f Taught by Ilya Sapozhnikov (Isapoz)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupPas encore d'évaluation

- The Brain and Cranial NervesDocument82 pagesThe Brain and Cranial NervesImmanuel Ronald LewisPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Sports Medicine and Health ScienceDocument9 pagesSports Medicine and Health ScienceJavier Estelles MuñozPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Sensate FocusDocument13 pagesSensate FocusMari Forgach100% (1)

- (Art) Chunking Processesin The Learning ofDocument11 pages(Art) Chunking Processesin The Learning ofPriss SaezPas encore d'évaluation

- Atika School-5172016 - Biology Form 2Document14 pagesAtika School-5172016 - Biology Form 2DenisPas encore d'évaluation

- Nursing TheoriesDocument15 pagesNursing TheoriesPatrick Rivera Oca100% (1)

- Adaptations of Cellular Growth & Differentiation: @2022 PreclinicalsDocument27 pagesAdaptations of Cellular Growth & Differentiation: @2022 PreclinicalsJames MubitahPas encore d'évaluation

- Airway: Nursing Care PlanDocument3 pagesAirway: Nursing Care PlanPhoebe Kyles CammaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Head and Neck Block HandbookDocument50 pagesHead and Neck Block HandbookGrace Poon OnionPas encore d'évaluation

- Generic Name Brand Name Classification Mechanism of Action Indication Adverse Effects Nursing Considerations Cetirizine Pharmacological BeforeDocument2 pagesGeneric Name Brand Name Classification Mechanism of Action Indication Adverse Effects Nursing Considerations Cetirizine Pharmacological BeforeDenise Louise Po100% (4)

- Nursing Care PlanDocument22 pagesNursing Care PlanjamPas encore d'évaluation

- Accepted Manuscript: Ageing Research ReviewsDocument49 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Ageing Research ReviewsCarolina LucínPas encore d'évaluation

- Holter SolutionsDocument4 pagesHolter SolutionsgimenPas encore d'évaluation

- Anesthesia For LiposuctionDocument26 pagesAnesthesia For Liposuctionjulissand10Pas encore d'évaluation

- Case Pres NCP ProperDocument3 pagesCase Pres NCP ProperMyraPas encore d'évaluation

- Cardinal - IP DashboardDocument17 pagesCardinal - IP DashboardLja CsaPas encore d'évaluation

- DU MSC Zoology 2021 Entrance Paper PDFDocument15 pagesDU MSC Zoology 2021 Entrance Paper PDFSuchismita BanerjeePas encore d'évaluation

- Assessment of The Critically Ill Patients and Their FamiliesDocument48 pagesAssessment of The Critically Ill Patients and Their Familiesjhing_apdan100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)