Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

The Quicksands of Realism by Karl E. Meyer

Transféré par

Christine ArthurCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Quicksands of Realism by Karl E. Meyer

Transféré par

Christine ArthurDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

The Quicksands of Realism

World Policy Journal, Fall, 2001 by Karl E. Meyer

E. H. Carr: A Critical Appraisal Michael Cox, ed. Basingstoke, Hampshire, U.K.: Palgrave, 1999 Hans J. Morgenthau: An Intellectual Biography Christoph Frei Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001 Does America Need a Foreign Policy? Henry Kissinger New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001 Call it what you will--balance-of-power, realpolitik, or hardball--the worldview commonly known as realism is ascendant in George W. Bush's Washington. Regarding treaties, the position is crisply put by the president's national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, "The President of the United States was not elected to sign treaties that are not in America's interest." That presently applies to accords perceived as limiting America's freedom to fix emission standards, test anti-ballistic missiles, open for scrutiny our chemical arsenals, market handguns, or exempt U.S. military personnel from facing war crimes charges before a still-unborn international tribunal. Certainly the Bush team can be credited with candor. In Rice's words, "We are going to be honest with our allies about which treaties are in our interest and are dealing with the problems with which they purport to deal. And those that are not, we are not prepared to be a party to." (1) And why not? America's global authority is unrivaled, and it is the prerogative of the powerful to dispense with cant. This has always been the mode of discourse for masters of realism, from Machiavelli and Hobbes to the Iron Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. Its essence was classically expressed by Thucydides. During the Peloponnesian War, he relates, an Athenian envoy spared the fence-sitting islanders of Melos windy orations on right and wrong because "you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must." (2) It is likewise arguable that more blood has been spilled in futile wars waged by impassioned crusaders, invoking the sanction of God, flag, and ethnicity, than by their conservative opposites. One recalls what Bismarck said of the Balkans, that they were not worth the bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier.

Still, given the school's resurgence, it seems but fair to apply realism's rigorous sandpaper to its own modern apostles. Three books about or by the titans of realism--Carr, Morgenthau, and Kissinger--have appeared within the last year. A careful reading suggests that blindness about the sweep of events, wishful credulity about the powerful and prevarication to cover up lapses are not solely the weaknesses of gullible internationalists: realists, too, stumble into the common quicksand. Consider first the school's neglected British godfather, Edward Hallett Carr (1892-1982), scholar, journalist, and sometime diplomat. I Carr's present standing recalls the British economist John Maynard Keynes's observation that practical men who believe themselves exempt from any intellectual influences are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Similarly, Americans who pride themselves on their realism about power politics owe an unacknowledged debt to a defunct and wintry Briton who is mostly forgotten in this country. Jonathan Haslam's judicious and literate biography, The Vices of Integrity: E. H. Carr (1999) elicited but a single review in a nonacademic journal; nor has a ripple greeted E. H. Carr: A Critical Appraisal, edited by Michael Cox. (3) Yet Ted Carr, as his friends knew him, is among the formative figures in the study of international relations. Born in London to what he termed the "middle, middle class," young Ted was a scholarship student at Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating with a coveted double first in classics. Found unfit for military service in the First World War, he joined the Foreign Office in 1916, where he monitored the transit of goods to Russia via Sweden. "But it was the Russian Revolution which decisively gave me a sense of history which I have never lost," he relates in an unpublished memoir unearthed by Cox. When the Bolsheviks seized power, his diplomatic colleagues assumed they could not hang on for more than a week. "From the first," his memoir continues, "owing to some esprit de contradiction, I refused to believe this. I studied eagerly every bit of news, and the longer the Bolsheviks held out, the more convinced I became that they had come to stay. It was a lucky hunch." Carr, bred on his family's Liberal principles, recalls that at the time he knew little of Marx, nothing of Marxism. In 1919, Carr was among the junior diplomats at the Versailles Peace Conference. "My Liberal principles were still intact," he writes. "Also, like many members of the British delegation (not only the Liberals), I was outraged by French intransigence and by our unfairness to the Germans, whom we cheated over the 'Fourteen Points' and subjected to every petty humiliation--the mood in which Keynes wrote his famous book." Posted to newly independent Latvia in the 1920s, Carr began learning Russian and was drawn to three formidable rebels, Dostoevsky, Herzen, and Bakunin, the subjects of his first books. In an acute and early American appraisal of Carr, Edmund Wilson in 1938 sensed something odd about Carr's frosty detachment, "perhaps a symptom of the decay of Great Britain." In reviewing the Bakunin biography, Wilson gave high marks to Carr's careful research and impartiality, but faulted his unremitting British chill, "which is always putting Bakunin in his place." You would hardly know from Carr's account, the review

complained, about the great anarchist's personal qualities-his audacity, exuberance, and irrepressible magnanimity-that so inspired his followers. (4) Carr's aloofness persisted; one senses he would have been baffled (he died in 1982) when similar traits enabled the Vaclav Havels, the Andrei Sakharovs, and the Lech Walesas to undermine the seemingly impregnable system that from the 1940s held Carr spellbound. Initially, Carr viewed the Soviet experiment with critical sympathy. He visited Moscow in 1927 and 1936, and was aware of Stalin's purges, and of the great famines that claimed millions of lives; he chided pilgrims like George Bernard Shaw who closed their eyes to these horrors. Yet like them, he was impressed by the apparent triumphs of Stalin's Five Year Plans. The Soviets, he wrote in 1931, "have discovered a new religion of the Kilowatt and the Machine, which may well prove to be the creed for which modern civilisation is waiting.... [The important question is] whether Europe can discover in herself a driving force, an intensity of faith, comparable to that now being generated in Russia." By then, Carr was posted to the League of Nations, a critical station on his intellectual via crucis, and in Geneva he witnessed first hand the League's inglorious decline. In 1936, his career took an improbable turn. He resigned from the diplomatic service to assume the Woodrow Wilson Chair of International Politics at the University College of Wales. Since the chair was established in 1925 to promote Wilson's ideals, which Carr viewed as illusory, it was like offering a cardinal's hat to a free-thinker. The fruit of this odd match was Carr's bold and path-breaking treatise, The Twenty Years' Crisis: 1919-1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations. It was written, its author said, "with the deliberate aim of counteracting the glaring and dangerous defect of nearly all thinking, both academic and popular, about international politics--the almost total neglect of the factor of power." To assume the beneficent influence of international law was, in Carr's view, a utopian delusion; even its advocates admitted that what passed for arbitration was in reality "an array of wigs and gowns vociferating in emptiness." Further, the belief in a universal interest in peace bore clear marks of its wishful AngloSaxon origin. People in English-speaking nations might well contend after 1918 that war was wrong and irrational, but that would hardly convince Germans, among others, since they twice profited from wars, in 1866 and 1870, and since they attributed their recent sufferings not to war but to its loss. The unpalatable truth, Carr pursued, was that asserting a shared interest in peace enabled politicians and political writers to ignore deep divergences between states benefiting from the status quo, and states anxious to disrupt it. Carr approvingly quotes the British scholar A. V. Dicey ("Men come easily to believe that arrangements agreeable to themselves are beneficial to others") and with scalpel and tweezers exhumes utterances illustrating the point by Woodrow Wilson and Lloyd George, and such avatars of internationalism as Alfred Zimmern and Arnold Toynbee, Norman Angell and Leonard Woolf--and most especially his bete blanche, Lord Robert Cecil of Chelwood, the foremost British champion of the League of Nations, who had the ill luck on September 10, 1931, to inform the League's Council: "There has scarcely ever been a period in the world's history when war seems less likely than at the present." Eight days later, Carr notes with a twist of his tweezers, Japan invaded Manchuria. II

Yet much the same embarrassment awaited Carr. Twenty Years' Crisis went to press in mid-July 1939, and passed into page proofs that September as Germany invaded Poland-too late for substantial revisions. Left intact were passages applauding Neville Chamberlain as a realist and citing the Munich Agreement that dismembered Czechoslovakia as a model of peaceful change, notwithstanding Hitler's threat of force, since yielding to such threats was a normal part of peaceful change Carr thus elaborated: "If the power relations of Europe in 1938 made it inevitable that Czecho-Slovakia should lose part of her territory, and eventually her independence, it was preferable (quite apart from any question of justice or injustice) that this should come about as a result of discussions round a table in Munich rather than as a result either of a war between the Great Powers or of a local war between Germany and Czecho-Slovakia." Still, Carr acknowledged more in sorrow that the Fuhrer somehow failed to get the point. In the author's words, following Munich "Herr Hitler himself seemed morbidly eager to emphasize the element of force and to minimize that of peaceful negotiation--a trait psychologically understandable as a product of the methods employed by the Allies at Versailles, but none the less inimical to the establishment of a procedure of peaceful change"--a masterful example of British understatement. The passages just quoted were expunged from the second edition of Twenty Years' Crisis, along with much else, shrinking the original 313 pages to 244 (for collectors, the two editions, with their seamless sutures, are prize trophies). It is this slimmed-down version that would become a classic in its genre, read with a certain frisson by a postwar generation of American graduate students (myself among them). Yet after the outbreak of the Second World War, with what might seem quixotic single-mindedness, Carr turned hopefully to Stalin, his new knight of power. In 1941, he became an assistant editor of The Times, and for five years wrote most of its commentary on foreign affairs at a moment when the venerable London daily was deemed a mouthpiece for the Foreign Office. Hence the resonance, and the indignation among Carr's critics, when The Times editorially likened Soviet domination of Eastern Europe to British imperial rule, adding that the British ruled slightly more efficiently. In his articles, Carr envisioned a postwar order dominated by the Big Three, with a soft peace accorded a unified Germany so that an integrated Europe might serve as a counterweight to the United States and the Soviet Union. Much that he wrote was prescient, much echoed mainstream thinking among the British political elite, but there was an undercurrent of admiration for Stalin as a realist that set Carr apart. Writing for the Partisan Review in 1944, George Orwell sardonically noted that among the intelligentsia, "all the appeasers, e.g. Professor E. H. Carr, have switched their allegiance from Hitler to Stalin" (these hard words did not diminish Carr's high regard for Orwell, a kindred realist). (5) As allied unity and his hopes for a global triumvirate foundered, Carr viewed the advent of the Cold War with his customary basilisk eye, distrustful of the United States and its moralizing diplomacy, and believing that Western society was destined for decline or decay. It was in this mood that he returned to scholarship, having embarked in 1944 on his 14-volume History of Soviet Russia, a project completed 33 years later when its author was 85. It was, as commonly remarked, a monumental achievement, yet like many monuments, it is less impressive on closer scrutiny. Carr seemed invariably to side with winners, as if a political variant of natural selection validated their choices. In the words of R. W. Davies,

Carr's otherwise admiring collaborator, "Carr tended not to take seriously groups, individuals and causes, whose policies were impracticable and doomed to failure. In his account of the Russian Revolution, Constitutional Democrats, Mensheviks and anarchists all appeared in his pages but were not granted much space. When I was working with him on Foundations of a Planned Economy, 1926-1929, Vol. 1 (1969) he argued that in a history of the Soviet 1920s it would be ridiculous for economist Bazarov to receive as much attention as the leading Gosplan officials who were making policy." (6) As damaging was Carr's persistent neglect of the human factor. His characters move like automatons from party congresses to central committee meetings, grinding out decrees and resolutions, all faithfully preserved in Carr's pages. This prompted a justifiable protest by Bertram Wolfe, author of the more warm-blooded Three Who Made the Revolution. In Carr's history, Wolfe remarks, "There is doctrine, but no clash of ideologies or faiths; famine, but no hunger; revolution, but no bloodshed. Titanic social transformations are ascertained in documents bereft of conflict, tears, or exultations." (7) Yet Carr not only minimizes the enormous human cost of Soviet rule, all but ignoring the blood purges and the Gulag, but does so in behalf of a fatally flawed theory of the future, indeed, a theory redolent of the wishful soppiness that Carr scorned. III Carr's theory was set forth in 1961 at Cambridge University in the George Macaulay Trevelyan Lectures, later published as What Is History? a little masterpiece of its genre. Here is Carr at his most attractive: learned, witty, and dealing with themes of the highest importance. Here he genially jousts with his adversaries, notably Isaiah Berlin and Karl Popper, while debunking the notion that the "facts" of history are an inviolable entity, independent of the historian. He does not quarrel with the need for accurate citation of sources, but cites the admonition of his onetime teacher, A. E. Housman, "Accuracy is a duty, not a virtue." Carr makes the bigger point with a graphic image: "The facts are really not at all like the fish on the fishmonger's slab. They are like fish swimming about in a vast and sometimes inaccessible ocean; and what the historian catches will depend partly on chance, but mainly on what part of the ocean he chooses to fish in and what tackle he chooses to use--these two factors being, of course, determined by the kind of fish he wants to catch. By and large, the historian will get the kind of facts he wants." However, not content with contesting the large and unwarranted claims made for Clio by her devotees, Carr advances a novel claim of his own, i.e., that history can become a form of science and that its skilled practitioners can, like the haruspices in ancient Rome, glimpse things to come. He writes: "Good historians, I suspect, whether they think about it or not, have the future in their bones. Besides the question: Why? the historian also asks the question: Whither?" Or as he further observes, "History properly so called can be written only by those who find and accept a sense of direction in history itself." And what was that direction? Guardedly, and allowing for set-backs, Carr discerned humankind's steady move upward, along a path illuminated by reason, as abler leaders continually discover what works best. Like his Victorian forebears at Cambridge, Cart saw "History as Progress," the penultimate chapter title in his book.

Yet Carr's Progress did not signify, as it did for Victorians, the global expansion of free trade, market economies, and parliamentary democracy; it signified instead the expansion of reason, as exemplified by the gains for education under Soviet rule, and the beginnings of that process in Asia and Africa. And in the economic sphere, he had no doubt that planning was more rational than laissez-faire. Granted, planners can behave irrationally and foolishly, "but the criterion by which they must be judged is not the old 'economic rationality' of classical economics. Personally, I have more sympathy with the converse argument that it was the uncontrolled, unorganized laissez-faire which was essentially irrational, and that planning is an attempt to introduce 'economic rationality' into the process." The world had moved "from laissez-faire to planning, from belief in objective economic laws to belief that man by his own action can be the master of his own economic destiny." Hence his decision to devote three volumes in his monumental history to the foundations of the Soviet planned economy, 1926-29, perhaps the most learned yet misguided epitaph ever penned to a failed economic system. In his bones, Carr sensed the future, and it worked. The process was irreversible; he had little patience with the "might-have-been" school of history. The historian writes of the Norman Conquest and the American Revolution as if what happened was bound to happen and is not accused of being a determinist by failing to discuss the opposite possibility. "When, however," he goes on, "I write about the Russian Revolution of 1917 in precisely this way--the only proper way for historians--I find myself under attack from my critics for having by implication depicted what happened as something that was bound to happen." To consider what "might have happened," he held, was a parlor game. Posterity played a devilish trick on Ted Carr. The system born of an irreversible revolution slipped off its steel rails in 1991. As Carr's collaborator, R. W. Davies, acknowledges, "The collapse of the Soviet planned economy would have appalled him." (8) One interesting consequence in the field of history has been the revival of the "what-if' school, detailing how contingent factors, personal traits, and unintended consequences can trigger human earthquakes. No less than five substantial "what-if' books have been published in the last three years. In sum, it seems fair to say that Carr the realist proved wrong about Hitler, about history, about the dark side of communism, and about the triumph of planning. By contrast, his closest American counterpart, Hans Morgenthau (1904-80), was wrong mostly about the United States. IV The study of international relations, or IR in academic parlance, is scarcely in its puberty. When Leonard Woolf wrote International Government in 1916, he was surprised to discover that his was the first such systematic survey. The earliest textbook of any consequence appeared in 1933: International Politics by Frederick Schuman, the Woodrow Wilson Professor of Government at Williams College. We have already mentioned Carr's Twenty Years' Crisis (1939). But beyond doubt, Hans Morgenthau's Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, which made its debut in 1948, has been the

most influential text in the field, and deservedly. It has gone through six editions and is said to have single-handedly established the modern study of IR in the United States. Written with bite and provocative in its judgments, Politics Among Nations still unsettles. Morgenthau reminds Americans, for example, that in the age of kings, when there was an "Aristocratic International," a common code of morality, buttressed by self-interest, stayed the hands of slaughter. As he explains, "When we say that George III of England was subject to certain moral restraints in his dealings with Louis XIV of France or Catherine the Great of Russia, we are referring to something real, something that can be identified with a conscience and the actions of certain specific individuals. When we say the British Commonwealth of Nations, or even Great Britain alone, has moral obligations toward the United States or France, we are making use of a fiction." Moreover, with the rise of democracy, traditional restraints have become even feebler since the ordinary voter has no moral conviction of a supranational character whatsoever. Unsurprisingly, his index (in the fourth edition, 1968) contains no entry for human rights, and his text devotes only cursory sentences to mass killings, the Nuremberg trials, and genocide. In unhappy reality, he remarks, whenever a nation appeals "to the conscience of mankind" or "world public opinion," it appeals to nothing real. (9) As a Jew who came of age in Weimar Germany, Morgenthau needed little instruction on the frailty of "world opinion." Born in Coburg, once an independent duchy and today part of Bavaria, he was an adolescent when he saw posters reading "Kill the Jewish Swine" on Spitalgasse, where his family lived. (Coburg later became the first German city to bestow honorary citizenship on Hitler.) In this milieu, young Hans paid dearly for his brains. As Cristoph Frei relates in his valuable biographical study, the best student at Coburg's gymnasium had the traditional honor of laying a wreath on the statue of the school's ducal founder, and of delivering his class farewell. In 1922, the distinction fell to Morgenthau, the first Jew so honored. An ugly anti-Semitic outbreak ensued. When young Hans spoke, the incumbent duke held his nose to show his contempt for a stinking Jew. "Nobody would speak to me," Morgenthau recalled. "...And people would spit at me and shout at me.... It was absolutely terrible, absolutely terrible...probably the worst day of my life." From there, Morgenthau's odyssey has a familiar ring. His university years were in Munich, the cradle of National Socialism, where he imbibed the liberal but nationalist precepts of Max Weber. In Berlin, he dueled verbally with the ice-cold, pro-Nazi philosopher Carl Schmitt (whose epigram was "He who says 'rights of man' lies"). In 1931, he left Germany to teach law in Geneva, and then moved on to Madrid just as the Spanish Civil War broke out. After emigrating to the United States in 1937, he obtained bottom-rung teaching posts, first at Brooklyn College, then at the University of Kansas before accepting a part-time appointment in 1943 at the University of Chicago, whose faculty he graced thereafter as Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Modern History. Morgenthau was dismayed by America's seeming political naivete. "They literally don't know what I am talking about," he lamented in 1947. It became his life's mission to confront and arouse, to make his adopted country see the world as it really was. This he did in a stream of books and articles espousing the doctrines of realism. As the Cold War

unfolded, he approved America's military buildup, the creation of NATO, the Marshall Plan, but early on became uneasy about the contain-communism-everywhere rhetoric in Harry Truman's 1947 call for military aid to Greece and Turkey. The Truman Doctrine, he feared, "transformed a concrete interest of the United States in a geographically defined part of the world into a moral principle of worldwide validity, to be applied regardless of the limits of American interest and power." Such a doctrine conflicted with his "Four Fundamental Rules" for American diplomacy: 1) diplomacy must be divested of the crusading spirit; 2) the objectives of foreign policy must be defined in terms of national interest and must be supported with adequate power; 3) diplomacy must look at the political scene from the point of view of other nations; and 4) nations must be willing to compromise on all issues that are not vital to them. To this doxology, he added five corollaries, the most important being never put yourself in a position from which you cannot retreat without losing face and from which you cannot advance without grave risks. Hence Morgenthau's mounting disquiet with America's involvement in Vietnam, which he outspokenly opposed as early as 1961, and whose demerits he spelled out in 1966 in a Look magazine debate with his German-born colleague Henry Kissinger. Yet at least initially, his dissent was divorced from moral considerations, as pointed out in a discerning New Republic essay on Morgenthau by Richard Wolin: "He was right about Vietnam, but for the wrong reasons. In retrospect, what contributed most to discrediting the international relations paradigm were realism's dubious and incessant justifications of the war in Vietnam. The inability to do justice to the moral dimension of international politics was one of realism's major weaknesses." (10) As Wolin notes, Morgenthau even cited the Nuremberg trials as an instance of American moralism. It thus came about that Morgenthau now found himself in the same antiwar movement alongside liberal internationalists like Sen. J. William Fulbright, with radical pamphleteers like I. F. Stone, and more comfortably, with Walter Lippmann, doyen of columnists and a fellow sphere-of-influence realist (who, this writer recalls, was derided as "gaga" by William Bundy, Lyndon Johnson's assistant secretary of state for Asia). And as the arguments warmed, Morgenthau himself veered to moral arguments, earning a chilly rebuke from Henry Kissinger in Diplomacy for this statement decrying American immorality: "When we talk about the violation of the rules of war, we must keep in mind that the fundamental violation, from which all other specific violations flow, is the very waging of this kind of war." (11) Dare one say that Morgenthau's intellectual hegira suggests a certain naivete on the distinguished professor's part? America, after all, may be of Europe but is not like Europe. Just as there are no European counterparts for Jefferson, Lincoln, or Wilson, an American version of Bismarck is inconceivable. As Tom Paine was among the first to declare, America is the last great hope for all humankind, its proudest symbol a noble bronze statue, paid for by French school-children, whose lamp shines in New York harbor. The sum of these differences is expressed in the jargon term "American exceptionalism." Its full significance to this day seems to escape proponents of realism, notably Henry Kissinger.

V Detractors who hoped the worst for Kissinger's latest book, Does America Need a Foreign Policy? are likely to be disappointed. It is for the most part a fluent exposition of America's current global choices, replete with thoughtful asides. He notes, for example, that in the modern age "territory has lost much of its significance as an element of national strength; technological progress can enhance a country's power far more than any conceivable territorial expansion." As an example, he adduces Singapore and Israel. That being so, a reader may ask, why do Israelis insist on holding slices of the West Bank coveted by Palestinians, one of the pivotal issues that doomed last fall's Camp David peace talks? Doubtless Kissinger would have a fluent response, but his book's merit is that it induces thought, about NATO expansion, or Taiwan policy, or Nelson Mandela, here anointed "as the embodiment of courage fortified by spiritual profundity." There is less of the defensiveness that so pervaded his three volumes of memoirs. Here we encounter Kissinger Mark III, the aging Nestor advising the student prince in Washington: ripe, mellow, even at times magnanimous, very different from Mark I, the gloomy theorist of nuclear strategy, or Mark II, the chronicler of the Nixon-Ford years, who hardly ever admits to a blunder. But there is a constant in all Kissingers: a disabling blind spot on the subject of human rights. This was evident in his first book, A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812-22 (1957), a work acclaimed by his admirers as a master key to his diplomacy. In his analysis of the Congress of Vienna, the author devotes less than a sentence in 354 pages to the epochal decision to abolish the slave trade. At Vienna, owing principally to the stubborn diplomacy of Viscount Castlereagh, the British foreign secretary, the allied powers unanimously condemned the inhuman traffic, and took unprecedented steps to enforce abolition. The allies agreed to establish a multinational "watching committee" in London, the first of its kind; and to secure Spanish and Portuguese compliance, Britain (and its taxpayers) paid the two countries [pounds sterling]700,000. It was further proposed at Vienna, also for the first time, that countries or colonies that refused to abolish the slave trade should be barred from European markets, an idea revived by the Russian tsar in 1817--"the first appearance in diplomatic practice," writes the British author and diplomat Harold Nicolson, "of the peacetime imposition of economic sanctions." (All these decisions, marking the birth of the global human rights movement, are described at length in Nicolson's The Congress of Vienna [1946].) Nor is it easy to find any signs of serious concern with human rights during Kissinger's eight years at the elbows of Presidents Nixon and Ford. First as national security adviser, then as secretary of state, he regarded the Jackson-Vanik amendment--tying most-favored nation trade status to liberalizing emigration rules in the Soviet bloc--as a misguided diversion from the realism of detente. His reluctance to confront the Soviet leaders on human rights contributed to the 1975 debacle in which Alexander Solzhenitsyn was denied a meeting with President Ford, though Kissinger devotes many pages in the third volume of his memoirs explaining that he was away from Washington when the nonevent occurred,

that those favoring the encounter had bad motives, and so forth and so on. It remains that the most eloquent of Russian dissidents got a White House brush-off. By the same token, Kissinger's Years of Renewal (1999) makes the surprising claim that the Ford Administration wrested a "strategic victory" in exploiting the human rights provisions of the 1975 Helsinki Accords. In fact, as detailed in a careful essay by Robert Kagan in the New Republic, "Kissinger at the time took little if any interest in the so-called 'human rights' issues of Basket III in the Helsinki Final Act. It would have been out of character for him to do so in any case, nor would pressing the human rights issue have fit well within his strategy of detente. In none of his writings before this new volume of memoirs did Kissinger ever pretend to take those issues seriously." Even in his recent book Diplomacy, Kagan continues, Kissinger claimed no role in pushing Basket III, "stating only, and with perhaps deliberate opacity, that 'the American delegation contributed' to the final provisions." (12) In his memoirs, however, Kissinger asserts that "the Western democracies pushed Basket III and peaceful change to exploit what we had come to recognize as the latent vulnerabilities of the Soviet empire." Kagan comments, "That 'we' is a clever bit of legerdemain." It was Jimmy Carter, not an idol of the realist school, who placed human rights at the heart and soul of American foreign policy, and who gave the policy teeth by applying it to rightwing dictatorships as well as the usual leftist suspects. And it was Ronald Reagan, though liberals gag at acknowledging the point, who rattled the Soviet leadership with his "evil empire" taunt, who impulsively proposed an unworkable missile defense system that threw his adversaries off balance, and who ultimately embraced Mikhail Gorbachev. As Kagan argues, it is unseemly for Kissinger to claim a continuity between his detente. strategy and Ronald Reagan's loose-cannon diplomacy that nonetheless helped end the Cold War. VI More interesting than Kissinger's refighting of battles past are his current views on human rights issues facing the Bush team. He finds little good to say about "humanitarian intervention," makes a case for traditional doctrines of sovereignty, and devotes the final section of his new book to an attack on the proposed International Criminal Court and the concept of "universal jurisdiction" for prosecuting war crimes. "Whatever one's view of the obsolescence of the doctrine of national sovereignty," Kissinger writes, "the combination of flagrant disregard of it by an alliance of democracies and its truculent diplomacy amounted to a departure from the very international norms on which those democracies had insisted throughout the Cold War. As a consequence, a glaring gap opened up between the claims of the various allied leaders extolling their new ethical foreign policy and the reaction of most of the rest of the world." To developing countries, the doctrine of humanitarian intervention is a form of neocolonialism: China rejects it, Russia is wary, even Europeans are having second thoughts. As Kissinger goes on, "In these circumstances, the doctrine of universal interventionism may in time redound against the very concept of humanitarianism. Once the doctrine of universal intervention

spreads and competing truths begin to fight each other, we may be entering a world in which, to use G. K. Chesterton's phrase, 'virtue runs amok.'" One reads this defense of national sovereignty with wonder, recalling that Kissinger as a cold warrior covertly worked to depose the elected leaders of Chile and Greece, favored the secret bombing of neutral Cambodia and an armed rebellion against leftists in Angola, gave tacit assent to Indonesia's invasion of newly independent East Timor, and secretly promoted a Kurdish uprising in Iraq. Is it his argument that when democracies covertly intervene, it is a justifiable intervention, but when democracies openly collaborate to prevent genocide, it is virtue run amok? Just what does he mean by suggesting that allied diplomacy in former Yugoslavia is "truculent," that the Balkans are a "bottomless pit," and that there is no American national interest that justifies risking lives to bring about a multiethnic state in Bosnia? One can fully acknowledge Balkan ambiguities, but in Kissinger's language there is an uneasy echo of Neville Chamberlain's claim that Czechoslovakia was a faraway country about whose people Britain knew little. Indeed, it is not so much what he says, but how, that finally sets one's teeth on edge. Never to my knowledge has Kissinger acknowledged the terrible human price exacted by his own realpolitik; he is literally and utterly shameless. Thus on one page he writes, "It is an important principle that those who commit war crimes or systematically violate human rights should be held accountable. But the consolidation of law, domestic peace, and representative government in a nation struggling to come to terms with a brutal past has a claim as well. The instinct to punish must be related, as in every constitutional democratic structure, to a system of checks and balances that includes other elements critical to the survival and expansion of democracy." Yet a few pages later, having said that war criminals should be held accountable, Kissinger writes in alarm that the legal weapon for doing so, universal jurisdiction, means "any leader of the United States or of other countries" could be "hauled before international tribunals established for other purposes." This truly caricatures the arguments over the proposed International Criminal Court. So angry is Kissinger that he now supports a bill before Congress that would all but scuttle the court in the name of protecting American military personnel from prosecution. Sponsored by House Whip Tom DeLay and Sen. Jesse Helms, the measure would forbid Americans from cooperating in any way with the projected court. The true purpose of the legislation is apparent in its provision that U.S. personnel could take part in U.N. peacekeeping operations only if the Security Council expressly immunizes Americans from the court's jurisdiction. That would also apply to any countries where Americans served-no immunity, no GIs. Nor could Washington give military aid to any country ratifying the ICC treaty, unless that country were a NATO partner, a designated ally, or had granted immunity to U.S. personnel. Thus here we have Henry Kissinger, who now suggests he always knew that Lech Walesa and Vaclev Havel would triumph, making common cause with Jesse Helms. The proposed court obviously deserves critical analysis, but there is an unbridgeable canyon between

efforts to mend or end it. We thus return full circle to Condoleezza Rice's comments on treaties. The Bush administration unilaterally claims the right to exempt the United States from international accords that we do not fully approve, or that inconvenience us, or that are less than perfect. By the same token, does that mean other nations can unilaterally opt out of arrangements of which they disapprove, on such matters as drug trafficking (after all, a demand rather than a supply problem), or immigration (do not look to us to protect your coastline and frontiers), or protecting intellectual property (imposed on us to fatten pharmaceutical profits), or giving special legal privileges to personnel at overseas American bases (a license for rapists)? Or does the privilege of demanding compliance with America's views on handguns, for example, belong exclusively to Americans? Certainly as a matter of power, Americans for now can get away with it--as did the Athenians in slaughtering the men of Melos, and enslaving their women and children, yet one also recalls that Sparta won the war. The new Bush Doctrine on treaties seems to be that America is free to exempt itself from the accountability, fair play, and most of all, reciprocity, that we routinely demand of others. This is realism? Karl E. Meyer is editor of World Policy Journal. Notes (1.) Condoleezza Rice's comments are from the transcript of the CBS television program, "Face the Nation," in an interview with Bob Schieffer on August 29, 2001. (2.) R. B. Strassler, ed., The Landmark Thucydides, book 5, para. 89. Trans. Robert Crawley (New York: Free Press, 1996). (3.) Outstanding among the few American reviews of Haslam's biography was that by Robert Conquest, "Agit-Prof," The New Republic, November 1, 1999. (4.) Edmund Wilson, "Cold Water on Bakunin," The New Republic, December 7, 1936, reprinted in Wilson's Shores of Light (New York: Farrar, Straus and Young, 1952), pp. 716-21. (5.) George Orwell, letter to Partisan Review, April 17, 1944, quoted in Jonathan Haslam, The Vices of Integrity (New York: Verso, 1999), p. 100. (6.) R. W. Davies, "Carr's Changing Views of the Soviet Union," in E. H. Carr: A Critical Appraisal, ed. Michael Cox (Basingstoke, Hampshire, U.K.: Palgrave, 1999), p. 91. (7.) Quoted in Haslam, Vices of Integrity, p. 145. (8.) Davies, "Carr's Changing Views," p. 107. (9.) The sixth edition of Politics Among Nations (New York: Knopf, 1985), written with Kenneth W. Thompson, did devote 4 perfunctory pages out of 688 to human rights.

(10.) Richard Wolin, "Reasons of State, States of Reason," The New Republic, June 4, 2001. (11.) Quoted in Henry Kissinger, Diplomacy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), p. 688. (12.) Robert Kagan, "The Revisionist," The New Republic, June 21, 1999, pp. 51-58. COPYRIGHT 2001 World Policy Institute COPYRIGHT 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- 04-LAN Technologies and PropertiesDocument23 pages04-LAN Technologies and PropertiesChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 03 - Topologies & WiringDocument89 pages03 - Topologies & WiringChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 08 IP SubnettingDocument39 pages08 IP SubnettingChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 13 2 Network SecurityDocument67 pages13 2 Network SecurityChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 11 WirelessDocument41 pages11 WirelessChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 07 IP AddressingDocument58 pages07 IP AddressingChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 06 TCP IpDocument56 pages06 TCP IpChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 13 1 Network ManagementDocument32 pages13 1 Network ManagementChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 05 Network DevicesDocument55 pages05 Network DevicesChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 14 TroubleshootingDocument58 pages14 TroubleshootingChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 10-Switching & VLANsDocument33 pages10-Switching & VLANsChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 12-Wide Area NetworkingDocument37 pages12-Wide Area NetworkingChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- The Caribbean - Towards A Better UnderstandingDocument13 pagesThe Caribbean - Towards A Better UnderstandingChristine Arthur100% (1)

- 02 Networking StandardsDocument71 pages02 Networking StandardsChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 09-2-IP Routing Protocol SummaryDocument1 page09-2-IP Routing Protocol SummaryChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- Dependency Structures As The Dominant Pattern in World SocietyDocument14 pagesDependency Structures As The Dominant Pattern in World SocietyChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 09-1-IP RoutingDocument30 pages09-1-IP RoutingChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- 01-Introduction To NetworksDocument38 pages01-Introduction To NetworksChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- MGMT 3017 Project 2 - Flexible TimeDocument8 pagesMGMT 3017 Project 2 - Flexible TimeChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- Capam TT Case Study 2005Document27 pagesCapam TT Case Study 2005Christine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- Programme WBSDocument1 pageProgramme WBSChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- New Public ManagementDocument2 pagesNew Public ManagementChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- Paladin #1 - GhostDocument265 pagesPaladin #1 - GhostRobert Scott VogtPas encore d'évaluation

- The Wooding ReportDocument298 pagesThe Wooding ReportChristine ArthurPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Banality Russia PDFDocument30 pagesBanality Russia PDFTaly RivasPas encore d'évaluation

- Was Stalin Necessary For Russia S Economic Development?Document64 pagesWas Stalin Necessary For Russia S Economic Development?Tomás AguerrePas encore d'évaluation

- F Eshraghi, AngloSoviet OccupationDocument27 pagesF Eshraghi, AngloSoviet OccupationPhilip AndrewsPas encore d'évaluation

- Cathy Bergin Bitter With The Past But Sweet With The Dream Communism in The African American Imaginary. Representations of The Communist Party, 1940-1952Document232 pagesCathy Bergin Bitter With The Past But Sweet With The Dream Communism in The African American Imaginary. Representations of The Communist Party, 1940-1952GabrielPas encore d'évaluation

- Webquest - Russian RevolutionDocument4 pagesWebquest - Russian RevolutionA PerrenodPas encore d'évaluation

- Olav Hofland - MA Thesis - Cooking Towards Communism - FINAL PDFDocument97 pagesOlav Hofland - MA Thesis - Cooking Towards Communism - FINAL PDFkarl hoffmannPas encore d'évaluation

- Who Was To Blame For The Cold WarDocument3 pagesWho Was To Blame For The Cold WarDavid ReesePas encore d'évaluation

- The Greening by Larry H. AbrahamDocument72 pagesThe Greening by Larry H. Abrahammacdave100% (1)

- Cold War Timeline (APUSH)Document14 pagesCold War Timeline (APUSH)NatalieTianPas encore d'évaluation

- Leon Trotskii Collected Writings 1930Document444 pagesLeon Trotskii Collected Writings 1930david_lobos_20Pas encore d'évaluation

- Behind The Curtains of The Balkan Wars - Leo Trotsky 1912Document8 pagesBehind The Curtains of The Balkan Wars - Leo Trotsky 1912aljabak85Pas encore d'évaluation

- Cambridge O Level: HISTORY 2147/01Document10 pagesCambridge O Level: HISTORY 2147/01M. Osama Zafar PirzadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary and Analysis of Chapter I and II of Animal FarmDocument36 pagesSummary and Analysis of Chapter I and II of Animal Farmloganrogers21100% (2)

- Michael David-Fox, Showcasing The Great ExperimentDocument410 pagesMichael David-Fox, Showcasing The Great ExperimentAdela NeiraPas encore d'évaluation

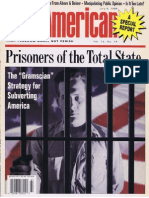

- Prisoners of The Total State: Gramscian Strategy For Subverting AmericaDocument39 pagesPrisoners of The Total State: Gramscian Strategy For Subverting AmericasrdivadPas encore d'évaluation

- Intellectuals and Assassins, S. SchwartzDocument4 pagesIntellectuals and Assassins, S. SchwartzManuel HernándezPas encore d'évaluation

- Origins Cold War TimelineDocument2 pagesOrigins Cold War TimelineedPas encore d'évaluation

- (Andrei Lankov) Crisis in North KoreaDocument297 pages(Andrei Lankov) Crisis in North KoreaCătălin Teniţă75% (4)

- Operational Art and Russian NarrativeDocument71 pagesOperational Art and Russian Narrativekonrad_novakPas encore d'évaluation

- Larry Patton McDonald Trotskyism TerrorDocument114 pagesLarry Patton McDonald Trotskyism TerrorAndemanPas encore d'évaluation

- Year 12 Modern History Soviet Foreign Policy 1917 41 ADocument2 pagesYear 12 Modern History Soviet Foreign Policy 1917 41 ANyasha chadebingaPas encore d'évaluation

- UkraineDocument60 pagesUkraineSachinJadhavPas encore d'évaluation

- Cold WarDocument12 pagesCold WarRadhika DhirPas encore d'évaluation

- Class 9 TH HISTORY CHAPTERDocument70 pagesClass 9 TH HISTORY CHAPTERAALEKH RANAPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 - Who Was To Blame For The Cold WarDocument18 pages4 - Who Was To Blame For The Cold Warlil NemoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Secret World of American Communism Harvey Klehr, John Earl HaynesDocument381 pagesThe Secret World of American Communism Harvey Klehr, John Earl HaynesRafael ParentePas encore d'évaluation

- Stalin - An Overview (Policies and Reforms)Document5 pagesStalin - An Overview (Policies and Reforms)itzkani100% (2)

- Cold War RoleplayDocument10 pagesCold War Roleplayapi-506897257Pas encore d'évaluation

- Review Unit 6 Pages 233-279Document46 pagesReview Unit 6 Pages 233-279api-237776182Pas encore d'évaluation

- How Successful Were Stalin's Economic PoliciesDocument2 pagesHow Successful Were Stalin's Economic PoliciesGuille Paz100% (1)