Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

About Identity Through Possible Worlds

Transféré par

Onur KabilDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

About Identity Through Possible Worlds

Transféré par

Onur KabilDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

About Identity Through Possible Worlds Author(s): R. L. Purtill Reviewed work(s): Source: Nos, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Feb.

, 1968), pp. 87-89 Published by: Wiley-Blackwell Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2214417 . Accessed: 01/10/2012 02:14

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley-Blackwell is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Nos.

http://www.jstor.org

About Identity Through Possible Worlds

R. L. PURTLL

WESTERN WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGE

In a recent exchange of papers Roderick Chishoim has criticized JaakoHintikka'ssuggestion that an individualin one possible world might be identical with an individual in another possible world, and Hintikka has replied to his criticism.' In this paper I want to point out certain inadequacies both of Chisholm'scriticism and of Hintikka'sreply. Consider the following case, which I argue is parallel to Chisholm'sprocedure: take a man who is plainly not bald, for example, Governor Ronald Reagan. Remove one hair from Governor Reagan'shead and he is still not bald. Remove another, and another .... Now plainly at some stage in this process we decide that GovernorReagan is now bald. It is not at all easy to identify this stage; certainly we cannot give an exact number of hairs removed which would make Reagan bald. Furthermore there are stages where we are not sure what to say, intermediate, "fuzzy" stages. But repetition of a process which initially does not make a difference eventually does make a difference. Now apply this to the stages by means of which Chisholm goes from Adam' in our world to Adamn in possible world Wn, from Noah' in our world. Initially, where Adam"is indistinguishable small changes in the descriptionof Adam' do not cause us to say that we have a new individual. But eventually it is reasonable to say that we have a new individual.It is not at all easy to say when this stage arrives, and there are intermediate stages where we would be in doubt what to say. But it seems clear that we can reasonablysay that Adam2is the same individual as Adam' withRoderick Chishoim, "Identity Through Possible Worlds, Some Questions," and Jaako Hintikka, "Individuals, Possible Worlds and Epistemic Logic," both in THIS JOURNAL, Volume I, Number 1 (March 1967).

87

88

NOUS

out thereby committingourselvesto saying that Adamnis the same individual as Adam'. And just as there is no reason to bring in the notion of some essential hair or hairs which make the difference between a non-bald Reagan and a bald Reagan, so there is no need to bring in the notion of some essentialpropertyor properties whose presence makes Adam2the same as Adam', and Adamnnot the same as Adam'. Perhaps identity might survive many minor changes. However, certain properties could hardly be changed without a major change in character or history or both, and are in this sense essential. If Adam had been a woman his history could hardly have been the same, nor more arguably, his character. Surely sex is "essential" a way in which length of toenails, in or amountof change in one's pocket on a given day, is not. On the other hand, granted that we can talk of possible worlds in which "the same"individual appears with some characteristics altered, Professor Hintikka'sreply to Chisholm does not seem to be adequate. Hintikkasuggests that we use the same criteria to identify individuals in possible worlds which we employ when we re-identify individuals in our actual world. There are several difficulties,which may not be fatal to this project but which seem to make it very much more difficult than Hintikka seems to imagine. For example, suppose that I met a certain individual in London on April 1, 1953. Sometimelater I met a person who seems very similar to the individual I met, and wonder if he is the same individual. But I find that this individual was not in London on April 1, 1953, and thereforeconclude that he cannot possibly be the same individual. Put more generally, one feature of our criteria for re-identificationis a requirement which has sometimes been A called "bodilycontinuity"; is identical with B only if at all times the location of A is the same as the location of B. But this requirement can hardly be carried over without modificationwhen we talk of identifying individuals in possible worlds. For in some possible world there may be an individualwho is in every respect identical with the individual whom I met in London on April 1, 1953 in our actual world, except for the fact that in this possible world he was not in London on April 1, 1953. Surely if we want to call Adam2 the same person as Adam' we would want to call this individual the same person as the individual who in our actual world I met in London on April 1, 1953. Thus again we seem to be brought to the conclusion that it is reasonable to call two individuals in two possible worlds the

ABOUT IDENTITY

THROUGH POSSIBLE WORLDS

89

same if there is very substantial agreement in their history, character, etc. even though in some respects they are not completely identical. But since our normal criteria of re-identification require absolute identity, we can hardly use these normal criteria (at least not without modification) for identifying individuals between possible worlds. Perhaps Hintikka had some modification of our ordinary criteria in mind but if he did he fails to say so. Furthermore it is not at all easy to say just how our usual criteria need to be modified.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- New PM Onboarding ChecklistDocument2 pagesNew PM Onboarding Checklisttiagoars0% (1)

- A Detailed Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plannestor dones70% (47)

- ISU-ISU MORAL DR aTIDocument21 pagesISU-ISU MORAL DR aTICHIN YUN JIN U2Pas encore d'évaluation

- Post Deliberation ReportDocument14 pagesPost Deliberation Reportapi-316046000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Overview of Complementary, Alternative & Integrative MedicineDocument34 pagesOverview of Complementary, Alternative & Integrative MedicineSaad MotawéaPas encore d'évaluation

- DepEd LCP July3Document49 pagesDepEd LCP July3Jelai ApallaPas encore d'évaluation

- Kakuma Refugee Camp MapDocument1 pageKakuma Refugee Camp MapcherogonyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Massimo Faggioli From The Vatican SecretDocument12 pagesMassimo Faggioli From The Vatican SecretAndre SettePas encore d'évaluation

- Mean Median Mode - Formulas - Solved ExamplesDocument5 pagesMean Median Mode - Formulas - Solved ExamplesSoorajKrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bangalore UniversityDocument1 pageBangalore UniversityRavichandraPas encore d'évaluation

- Rujukan Bab 2Document3 pagesRujukan Bab 2murshidPas encore d'évaluation

- ETS Global - Product Portfolio-1Document66 pagesETS Global - Product Portfolio-1NargisPas encore d'évaluation

- BORANG PENILAIAN LAPORAN HM115 HTC297 - NewDocument2 pagesBORANG PENILAIAN LAPORAN HM115 HTC297 - NewafidatulPas encore d'évaluation

- Aasl Standards Evaluation Checklist Color 3Document3 pagesAasl Standards Evaluation Checklist Color 3aPas encore d'évaluation

- Oswal Alumni Assocation DraftDocument21 pagesOswal Alumni Assocation Draftnalanda jadhavPas encore d'évaluation

- Week 2-LS3 DLL (Mean, Median, Mode and Range)Document7 pagesWeek 2-LS3 DLL (Mean, Median, Mode and Range)logitPas encore d'évaluation

- Judge Rebukes Aspiring Doctor, Lawyer Dad For Suing Over Med School DenialDocument15 pagesJudge Rebukes Aspiring Doctor, Lawyer Dad For Suing Over Med School DenialTheCanadianPressPas encore d'évaluation

- Forehand Throw Itip Lesson Plan 1Document3 pagesForehand Throw Itip Lesson Plan 1api-332375457Pas encore d'évaluation

- FAQ About IVT TrainingDocument12 pagesFAQ About IVT TrainingJohanna ChavezPas encore d'évaluation

- Mha Acio Ib 2015 Admit CardDocument1 pageMha Acio Ib 2015 Admit CardArun Kumar GPas encore d'évaluation

- Social Media Student Learn Outcome: January 2019Document11 pagesSocial Media Student Learn Outcome: January 2019Jessica Patricia FranciscoPas encore d'évaluation

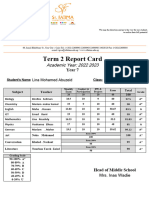

- ReportDocument1 pageReportLina AbuzeidPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 3 FLCTDocument67 pagesGroup 3 FLCTcoleyfariolen012Pas encore d'évaluation

- PR2 FInals Wk2 ModuleDocument5 pagesPR2 FInals Wk2 ModuleErick John SaymanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bco211 Strategic Marketing: Final Assignment - Fall Semester 2021Document3 pagesBco211 Strategic Marketing: Final Assignment - Fall Semester 2021TEJAM ankurPas encore d'évaluation

- Ngene C. U.: (Department of Computer Engineering University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria)Document17 pagesNgene C. U.: (Department of Computer Engineering University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria)Oyeniyi Samuel KehindePas encore d'évaluation

- Independent University, Bangladesh Department of Environmental Management Course OutlineDocument9 pagesIndependent University, Bangladesh Department of Environmental Management Course OutlineZarin ChowdhuryPas encore d'évaluation

- Typical & AtypicalDocument2 pagesTypical & Atypicalzarquexia 02Pas encore d'évaluation

- Umair Paracha: Contact InfoDocument2 pagesUmair Paracha: Contact InfoUmairPas encore d'évaluation

- IIPM Resume FormatDocument2 pagesIIPM Resume FormatBaljit SainiPas encore d'évaluation