Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

174 Opn 12

Transféré par

jspectorDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

174 Opn 12

Transféré par

jspectorDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

================================================================= This opinion is uncorrected and subject to revision before publication in the New York Reports. ----------------------------------------------------------------No.

174 The People &c., Respondent, v. Calvin L. Harris, Appellant.

William T. Easton, for appellant. Gerald A. Keene, for respondent.

PIGOTT, J.: Michele Harris, mother of four young children and defendant's estranged wife, was last seen on the evening of September 11, 2001. At approximately 7:00 a.m. the following

day, the Harris family babysitter, Barbara Thayer, discovered Michele's unoccupied minivan at the bottom of the quarter-mile

- 1 -

- 2 -

No. 174

driveway of the Harris residence, which is situated on a 200-acre estate in a remote area of Tioga County. Although the Harrises

were in the process of divorcing, they continued living in the same residence, albeit sleeping in separate rooms. After driving Ms. Thayer to the end of the driveway to retrieve Michele's vehicle, defendant, the owner of several car dealerships, left for work. When a friend of Michele's called

the Harris household and was told by Ms. Thayer that Michele had not returned home the night before, the friend called Michele's divorce attorney who, in turn, contacted state police. Later

that morning, police questioned defendant at his dealership concerning Michele's disappearance. Defendant accompanied police

to his home and consented to a search of his residence and Michele's minivan, eventually leaving the officers at the residence and returning to work. Later that day, defendant gave

police written consent to search his residence and vehicles. On September 14, 2001, evidence technicians discovered blood on the tiled floor of a kitchen alcove, on door moldings and surfaces leading to the garage and on the wall of the garage leading into the house. At that point, police obtained a search

warrant and, upon returning the following day, discovered blood on the garage floor as well.1 The weekend following Michele's disappearance,

Months later, police also examined a kitchen throw rug and discovered what appeared to be blood stains. - 2 -

- 3 defendant and his children visited defendant's brother in Cooperstown.

No. 174

During dinner, defendant's sisters-in-law Francine

and Mary Jo Harris confronted defendant about statements he had allegedly made to Michele. According to Francine and Mary Jo,

Michele told them in March 2001 that defendant threatened her by stating that he would not need a gun to kill her, that police would never find her body and that he would never be arrested.2 The police investigation, spanning several years, produced neither a body nor a weapon.

I. In 2005, defendant was indicted on one count of murder in the second degree. the spring of 2007. A jury convicted him of that offense in

The day after the verdict, a local farmhand

came forward with information that he had seen Michele and a man in his mid-20s at the end of the Harris driveway at approximately 5:30 a.m. on September 12, 2001. Armed with this new

information, defense counsel moved, pursuant to CPL 330.30, to set aside the verdict. The trial court granted the motion, and

its order was affirmed on appeal (55 AD3d 958 [3d Dept 2008]).

At the second trial, defendant denied making these statements. Francine and Mary Jo, however, testified that defendant initially denied making the statements, but then said that he may have said something like that but that did not mean that he was going to kill Michele. - 3 -

- 4 II.

No. 174

Given the high-profile nature of the case, there was significant media coverage in local newspapers and on television, including two national broadcasts, covering Michele's disappearance and defendant's first trial. Defense counsel made

two change of venue motions prior to the retrial, citing "prejudicial publicity." Each motion was denied, as was a third

motion made by defense counsel during jury selection. After a lengthy retrial that included extensive blood spatter and DNA evidence and testimony concerning threatening statements defendant purportedly made to Michele, a jury once again convicted defendant of murder in the second degree. The

Appellate Division, in a 3-1 decision, affirmed the judgment, holding, among other things, that the verdict was supported by legally sufficient evidence, that the trial court properly denied a for-cause challenge of a prospective juror made by defendant, and that the trial court properly allowed in evidence Michele's hearsay statements to Francine and Mary Jo for the limited purpose of allowing the jury to evaluate defendant's reaction to those accusations (88 AD3d 83 [3d Dept 2011]). The dissenting

Justice, in addition to arguing that the verdict was not supported by legally sufficient evidence, asserted that the trial court committed reversible error in denying defendant's for-cause challenge of the prospective juror and in giving an inadequate limiting instruction concerning Michele's hearsay statements to

- 4 -

- 5 Francine and Mary Jo. A Justice of the Appellate Division

No. 174

granted defendant leave to appeal.

We now reverse the order of

the Appellate Division and remit for a new trial.

III. The Appellate Division properly held that the guilty verdict was supported by legally sufficient evidence. However,

a critical error occurred during voir dire when Supreme Court failed to elicit from a prospective juror an unequivocal assurance of her ability to be impartial after she apprised defense counsel that she had a preexisting opinion as to defendant's guilt or innocence. At voir dire, the prospective juror acknowledged that she had followed the case in the media and that she had "an opinion slightly more in one direction than the other" concerning defendant's guilt or innocence. When asked by defense counsel if

her opinion would impact her ability to judge the case based solely on the evidence presented at trial, the prospective juror responded, "[H]ow I feel, opinion-wise, won't be all of what I consider if I'm on the jury," but admitted that it would be "[a] slight part" of what she would consider (emphasis supplied). Defense counsel challenged the prospective juror for cause on the ground that she could not say that her preexisting opinion would have no effect on her ability to sit as a fair juror. The trial court denied the challenge and defendant

- 5 -

- 6 utilized a peremptory challenge on the prospective juror.

No. 174

Defendant exhausted his peremptory challenges, and, therefore, preserved this issue for review (see CPL 270.20 [2]). CPL 270.20(1)(b) provides that a party may challenge a potential juror for cause if the juror "has a state of mind that is likely to preclude him from rendering an impartial verdict based upon the evidence adduced at the trial." We have

consistently held that "a prospective juror whose statements raise a serious doubt regarding the ability to be impartial must be excused unless the juror states unequivocally on the record that he or she can be fair and impartial" (People v Chambers, 97 NY2d 417, 419 [2002]; see People v Arnold, 96 NY2d 358, 363 [2001]; People v Johnson, 94 NY2d 600, 614 [2000]). "When

potential jurors themselves say they question or doubt they can be fair in the case, trial judges should either elicit some unequivocal assurance of their ability to be impartial when that is appropriate, or excuse the juror when that is appropriate," since, in most cases, "[t]he worst the court will have done . . . is to have replaced one impartial juror with another impartial juror" (People v Johnson, 17 NY3d 752, 753 [2011] citing People v Johnson, 94 NY2d 600, 616 [2000]). The prospective juror had a preexisting opinion concerning defendant's guilt or innocence that cast serious doubt on her ability to render an impartial verdict. At that point, it

was incumbent upon the trial court to conduct its own follow-up

- 6 -

- 7 inquiry of the prospective juror once she stated that her

No. 174

preexisting opinion would play only "[a] slight part" in her consideration of the evidence. Given the absence of that

inquiring, the trial court committed reversible error in denying defendant's for-cause challenge (see Johnson, 17 NY3d at 753). Finally, while the trial court properly allowed in evidence Michele's hearsay statements to Francine and Mary Jo for the limited purpose of providing context as to defendant's reaction upon being confronted with them, it erred in failing to grant defendant's request for a limiting instruction to the jury not to consider the statements for their truth. The trial court

acknowledged that Michele's statements constituted hearsay, but denied defendant's request for a limiting instruction because it did not "want to unnecessarily confuse the jury." It opted

instead to charge the jury that the statements constituted hearsay which would not normally be allowed in evidence because its truthfulness could not be tested under oath, and then stated: "You, the jury, may consider that testimony regarding this episode and determine what evidentiary value, if any, you choose to assign to the exchange that occurred between Mary Jo and Francine and Mr. Harris." The trial court's failure to issue the appropriate limiting instruction was not harmless. In a case where there was

no body or weapon, and the evidence against defendant was purely circumstantial, the danger that the jury accepted Michele's - 7 -

- 8 statements for truth was real.

No. 174

Although the court's instruction

explained why the statements were admitted in evidence, it failed to apprise the jury that the statements were not to be considered for their truth. This error was compounded when the prosecutor

in his summation relied on those statements as direct evidence that defendant had, in fact, murdered Michele and successfully hid her body, as he purportedly threatened Michele that he would do. We are not unsympathetic to defendant's claim that prejudicial and inflammatory pretrial publicity saturated the community from which the jury was drawn and effectively deprived defendant of a fair trial by an impartial jury. A significantly

high percentage of prospective jurors admitted to having heard about the case and nearly half had formed a preexisting opinion as to defendant's guilt or innocence. Notably, "as with so many

other cases, the problem encountered with jury selection is inextricably linked to the problem of venue," and although media saturation by its very nature is prejudicial, "it is unrealistic to expect and require jurors to be totally ignorant prior to trial of the facts and issues in certain cases" (People v Culhane, 33 NY2d 90, 110 [1973] [citations omitted]). Although our decision to reverse the conviction and order a new trial is premised upon the trial court's denial of the for-cause challenge and failure to issue the appropriate - 8 -

- 9 -

No. 174

limiting instruction, we are cognizant that publicity attending a third trial may render voir dire significantly burdensome. In

such a case, to counter the potential "temptation to relax the rules and accept a doubtful juror so that the case may proceed to trial," we expect the trial court to exercise "special vigilance to insure that the adverse publicity does not infect the adjudicating process" and, in such exercise, strongly consider changing venue if for-cause disqualifications "become legion," rendering voir dire "hopelessly burdensome" (Culhane, 33 NY2d at 110 n 4). We have considered defendant's remaining contentions and conclude that they are without merit. Accordingly, the order of the Appellate Division should be reversed and a new trial ordered. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Order reversed and a new trial ordered. Opinion by Judge Pigott. Chief Judge Lippman and Judges Ciparick, Graffeo, Smith and Jones concur. Judge Read dissents and votes to reverse and dismiss the indictment for the reasons stated in so much of the dissenting opinion of Justice Bernard J. Malone at the Appellate Division as addressed sufficiency of the evidence (88 AD3d 83, at 98-120). Decided October 18, 2012

- 9 -

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Sample Motion For Summary Judgment by Plaintiff For California EvictionDocument3 pagesSample Motion For Summary Judgment by Plaintiff For California EvictionStan Burman100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- Prevent corporate name confusion with SEC approvalDocument2 pagesPrevent corporate name confusion with SEC approvalAleli BucuPas encore d'évaluation

- Partnership Under The Civil Code of The Philippines Codal ProvisionsDocument17 pagesPartnership Under The Civil Code of The Philippines Codal ProvisionsKeerstine BatucanPas encore d'évaluation

- Robert C. Marshall v. Douglas County School Board, Et Al.: Motion For Preliminary InjunctionDocument12 pagesRobert C. Marshall v. Douglas County School Board, Et Al.: Motion For Preliminary InjunctionMichael_Roberts2019Pas encore d'évaluation

- Provisional Remedies: Preliminary AttachmentDocument51 pagesProvisional Remedies: Preliminary AttachmentJImlan Sahipa IsmaelPas encore d'évaluation

- CF Sharp vs Northwest AirlinesDocument1 pageCF Sharp vs Northwest AirlinesJed MacaibayPas encore d'évaluation

- 604 House Building - Loan Assoc. V Blaisdell (Alfaro)Document3 pages604 House Building - Loan Assoc. V Blaisdell (Alfaro)Julius ManaloPas encore d'évaluation

- SLU-BWD Agreement for BSBA Internship ProgramDocument3 pagesSLU-BWD Agreement for BSBA Internship ProgramAnonymous H2L7lwBs3Pas encore d'évaluation

- Affidavit of DenialDocument1 pageAffidavit of DenialTan-Uy Jefferson JayPas encore d'évaluation

- IG LetterDocument3 pagesIG Letterjspector100% (1)

- Joseph Ruggiero Employment AgreementDocument6 pagesJoseph Ruggiero Employment AgreementjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Pennies For Charity 2018Document12 pagesPennies For Charity 2018ZacharyEJWilliamsPas encore d'évaluation

- Cornell ComplaintDocument41 pagesCornell Complaintjspector100% (1)

- State Health CoverageDocument26 pagesState Health CoveragejspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Abo 2017 Annual ReportDocument65 pagesAbo 2017 Annual ReportrkarlinPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 08 18 Constitution OrderDocument27 pages2017 08 18 Constitution OrderjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Film Tax Credit - Quarterly Report, Calendar Year 2017 2nd Quarter PDFDocument8 pagesFilm Tax Credit - Quarterly Report, Calendar Year 2017 2nd Quarter PDFjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- SNY0517 Crosstabs 052417Document4 pagesSNY0517 Crosstabs 052417Nick ReismanPas encore d'évaluation

- Federal Budget Fiscal Year 2017 Web VersionDocument36 pagesFederal Budget Fiscal Year 2017 Web VersionjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Inflation AllowablegrowthfactorsDocument1 pageInflation AllowablegrowthfactorsjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- NYSCrimeReport2016 PrelimDocument14 pagesNYSCrimeReport2016 PrelimjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Teacher Shortage Report 05232017 PDFDocument16 pagesTeacher Shortage Report 05232017 PDFjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Hiffa Settlement Agreement ExecutedDocument5 pagesHiffa Settlement Agreement ExecutedNick Reisman0% (1)

- Class of 2022Document1 pageClass of 2022jspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Siena Poll March 27, 2017Document7 pagesSiena Poll March 27, 2017jspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- p12 Budget Testimony 2-14-17Document31 pagesp12 Budget Testimony 2-14-17jspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Opiods 2017-04-20-By Numbers Brief No8Document17 pagesOpiods 2017-04-20-By Numbers Brief No8rkarlinPas encore d'évaluation

- Oag Sed Letter Ice 2-27-17Document3 pagesOag Sed Letter Ice 2-27-17BethanyPas encore d'évaluation

- 2017 School Bfast Report Online Version 3-7-17 0Document29 pages2017 School Bfast Report Online Version 3-7-17 0jspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Youth Cigarette and E-Cigs UseDocument1 pageYouth Cigarette and E-Cigs UsejspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Darweesh Cities AmicusDocument32 pagesDarweesh Cities AmicusjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Review of Executive Budget 2017Document102 pagesReview of Executive Budget 2017Nick ReismanPas encore d'évaluation

- 16 273 Amicus Brief of SF NYC and 29 Other JurisdictionsDocument55 pages16 273 Amicus Brief of SF NYC and 29 Other JurisdictionsjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Schneiderman Voter Fraud Letter 022217Document2 pagesSchneiderman Voter Fraud Letter 022217Matthew HamiltonPas encore d'évaluation

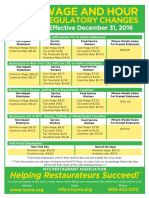

- Wage and Hour Regulatory Changes 2016Document2 pagesWage and Hour Regulatory Changes 2016jspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Activity Overview: Key Metrics Historical Sparkbars 1-2016 1-2017 YTD 2016 YTD 2017Document4 pagesActivity Overview: Key Metrics Historical Sparkbars 1-2016 1-2017 YTD 2016 YTD 2017jspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- 2016 Local Sales Tax CollectionsDocument4 pages2016 Local Sales Tax CollectionsjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Pub Auth Num 2017Document54 pagesPub Auth Num 2017jspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Voting Report CardDocument1 pageVoting Report CardjspectorPas encore d'évaluation

- Mecano Vs Commission On Audit. G.R 103982 Dec 11 1992Document6 pagesMecano Vs Commission On Audit. G.R 103982 Dec 11 1992Jen AniscoPas encore d'évaluation

- Law Finder: Judgment Prasenjit Mandal, J. - This Criminal RevisionDocument3 pagesLaw Finder: Judgment Prasenjit Mandal, J. - This Criminal RevisionGURMUKH SINGHPas encore d'évaluation

- People of The Philippines,: DecisionDocument12 pagesPeople of The Philippines,: DecisionGlendie LadagPas encore d'évaluation

- SNL 518-615 + 22218 K + H 318 SNL Plummer Block Housings For Bearings On An Adapter Sleeve, With Standard Seals - 20210901Document4 pagesSNL 518-615 + 22218 K + H 318 SNL Plummer Block Housings For Bearings On An Adapter Sleeve, With Standard Seals - 20210901thanh nguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Bharat Glass Tube Limited V Gopal Glass Works Limited - NilanjanaDocument2 pagesBharat Glass Tube Limited V Gopal Glass Works Limited - NilanjanaNn100% (1)

- Guerrero v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 137004, July 26, 2000Document6 pagesGuerrero v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 137004, July 26, 2000Judel MatiasPas encore d'évaluation

- Hear Both Sides: Audi Alteram PartemDocument10 pagesHear Both Sides: Audi Alteram PartemTanishq AhujaPas encore d'évaluation

- Bank of Augusta vs. EarleDocument2 pagesBank of Augusta vs. EarleRobinson MojicaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022 Aviation Finance Leasing India FINALDocument22 pages2022 Aviation Finance Leasing India FINALtmuthukumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Lost ID AffidavitDocument1 pageLost ID AffidavitJoan Coching-DinagaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pavan Duggal Cyber LawDocument46 pagesPavan Duggal Cyber LawPinky GandhiPas encore d'évaluation

- Berkeley Law & Technology Group, LLP v. Cool - Document No. 2Document7 pagesBerkeley Law & Technology Group, LLP v. Cool - Document No. 2Justia.comPas encore d'évaluation

- The Issue of Betterment in Claims For Reinstatement CostsDocument28 pagesThe Issue of Betterment in Claims For Reinstatement CostsWilliam TongPas encore d'évaluation

- HLURB Case Form No 06 SPA Complaint PDFDocument1 pageHLURB Case Form No 06 SPA Complaint PDFCeline-Maria JanoloPas encore d'évaluation

- South Wales Echo 11-04-2018 1ST p5Document1 pageSouth Wales Echo 11-04-2018 1ST p5Marcus HughesPas encore d'évaluation

- Areola V CADocument2 pagesAreola V CAJosef BunyiPas encore d'évaluation

- People Vs AtienzaDocument13 pagesPeople Vs Atienzajerale b carreraPas encore d'évaluation

- Business Organizations Outline SummaryDocument97 pagesBusiness Organizations Outline Summaryomidbo1100% (1)

- Edit AggrimentDocument8 pagesEdit AggrimentChethanPas encore d'évaluation

- Philippine Supreme Court upholds constitutionality of National Defense LawDocument1 pagePhilippine Supreme Court upholds constitutionality of National Defense LawKaira Marie CarlosPas encore d'évaluation

- De La Cruz vs. People of The Philippines - Special Penal LawsDocument2 pagesDe La Cruz vs. People of The Philippines - Special Penal Lawsحنينة جماءيلPas encore d'évaluation