Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Knowledge and Plato

Transféré par

Shabana AslamTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

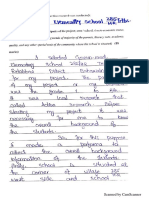

Knowledge and Plato

Transféré par

Shabana AslamDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Knowledge and Plato Knowing is always the apprehension of an object which is other than the knowledge of it, and

it is the apprehension of that object as it really is. Such knowledge may, for various reasons, be beyond the reach of you, or me, or of all mankind, but it is still true that to knowledge which really is what we mean by knowledge, to the knowledge of God for example, the whole scheme of reality would be transparent; there are limits to your knowledge, or to mine, but no limits to knowledge itself, no ground of knowledge itself impenetrable to mind. If there seems to be anything in the universe which is, in its own nature, incapable of being known through and through, we may be sure that this seeming reality is not truly existent, but is mere seeming. Plato is to re-interpret the forms as eternal objects. Eternal objects exist only as possibilities, until they become concrete through ingression into an occasion in space and time. As purely possible, such abstract entities have no value; apart from three limiting conditions, they stand to each other in all logically possible relations--a sharp contrast with Plato's notion of the determinate order of his world of form (in the strictest senses of form). In a restless universe, where novelty is part of the creative advance of life and nature, Whitehead insists that objective, actual forms would be a strait-jacket that does not fit in with what we actually experience. This has the corollary that ethical decisions cannot be made by reference to objective norms, but must depend on individual sensitivity to the choices which will, and those which will not, create more harmony and value. Such sensitivity is hard to appraise objectively, and whether it can be taught or even shared inter-subjectively, remains a question. The result seems a loss of the strongest feature of Plato's original position: that there is such a thing as an objective standard of right and wrong, good and bad, which can be the basis for ethics and law, as well as for logic and, perhaps, art.

The possibility of scientific knowledge is conditioned not by the existence of universals a parte rei, as Plato thought, but by the power which intellect possesses of abstracting and universalizing the natures which, independently of it, are concrete and individual. Universality, as Cajetan remarks in his Commentary on Aristotle, is not an object of science, but a condilio sine qua non of science. (Russell, 73) The objects of science may have a mode of real being other than the mode of their being known. In order to be known scientifically they must of course be intelligible, i.e. present to intellect in a manner conformable with the nature of the intellect. But this mode of their presence may be distinct from that of their real existence; and reflection on our processes of thought and sense perception, processes of the same self-conscious mind or soul, processes wherein we spontaneously recognize the objects of thought and the objects of sense to be identical in reality,--reflection on these processes convinces us that things really exist and reveal themselves to sense in modes other than those which they assume on becoming objects of thought. Cognition is not a passive mirroring, in our minds, of reality as it is. Therefore cognition is--as, indeed, consciousness itself testifies--an active process whereby the mind has to interpret what it becomes aware of. That of which it becomes aware is objective to it, is given to it, is real, is independent of it, i.e. the mind spontaneously believes the matter of its awareness to be all this: a belief which reflection has to examine and if so be to justify. But if what is thus given to the mind is reality, it is reality not as known but as knowable, not as interpreted but as calling for interpretation, not as revealed, discovered, or manifested, but as capable of being revealed, discovered, manifested by the process of mental interpretation or judgment. The main problems of knowledge are concerned with its objectivity and its truth. The distinctions between subject and object, subjective and objective, in knowledge, are of the first

importance; and as much confusion is caused by looseness of thought in regard to their meanings it is very necessary to understand the precise sense in which they are used in epistemology. In the spontaneous order men do not trouble as to how a reality distinct from the knowing subject can become present to him so as to be an object of his cognition: they simply believe that it can and does happen. Because they do not reflect they perceive no difficulty in it; whereas to some men, when they reflect seriously on it, the difficulty--of the knowing subject transcending himself to know a reality distinct from himself --seems so insuperable that they pronounce such a feat an impossibility, and declare their belief that all knowable reality in order to be knowable must be in some sense really identical with the knowing subject. They think that by this identification they surmount the insuperable difficulty. It would appear, however, on further reflection thatapart altogether from the other insuperable difficulty into which such identification leads them, viz. the difficulty of successfully avoiding solipsism--the identification does not wholly surmount the original or transcendence difficulty. And the reason why we think so is this. Even when the knowing subject by an act of reflex cognition knows himself or his own conscious states, processes, or activities, or whatever it be that is thus consciously achieved. The feature of universality, of being one-common-to-many, is intelligible only as a mental mode of a reality or object considered as a term of thought or conception, as present to or in some mind. The ontologists avoided the difficulty by regarding the universals as terms or objects of the Divine Thought in the Mind of the Deity. Now monistic realism appears to avoid it in another way: by boldly denying all distinction between the existence which reality has in and for the mind as an object of thought, and the existence which reality has in and for itself; by identifying the logical with the ontological, the thought-being or esse ideale of things, with their real being or esse reale; by proclaiming the duality of subject and object in

knowledge to be always and necessarily a purely mental or logical distinction and never a real distinction, i.e. to be always the result of a presentation of reality to itself, or an opposition of reality to itself. (Nicholas, vi) Thus reality, which is ever one and the same, ever self-identical, is at once subject and object, thought and thing, Mind and Nature, logical and ontological, ideal and real. If spontaneous beliefs in the reality of the abstract, universal objects of intellectual conception, and in the reality of the concrete, individual data of sense perception, be justifiable, then reality as apprehended by intellect in the form of abstract thought-objects, grounding absolutely necessary and universal relations, must be somehow, independent of the modes of concrete actual existence wherein that same reality reveals itself to sense. Not that the abstract objects of intellectual thought have, as such, an actual existence which would be wholly independent of, and apart from, the world of sense data, as some interpret Plato to have taught; or that we have intellectual intuitions of them which are immediate and innate in the sense of apprehending these objects independently of sense perception and of the reflex consciousness which reveals the individual mind in its conscious processes. No doubt, being a definite object of thought, and having a definite content or meaning whereby it can be consciously distinguished from other abstract thought-objects, it may be said to have a conceptual or formal unity; (Burnet, 81) but in its abstract, absolute condition, and as yet not consciously related by the intellect to the individual object or objects of sense, from which it was abstracted, or made an object of reflex intellectual contemplation, it can be truly said to be neither singular nor universal. Now the thought-object, considered in this abstract condition as object of direct intellectual conception, has been called by scholastics the direct, or metaphysical, or fundamental, or potential universal

Plato is the originator of epistemology. But if Barnes had taken the conception for granted he would have come to the same conclusion: there is just one philosopher -- Plato who first satisfies their criteria. But that conclusion exposes the unacceptability of their conception of epistemology. The epistemological enterprise is nothing, except arbitrarily, to be confined to the investigation, more or less methodical and systematic, of the questions these philosophers identify as basic for epistemology. Epistemological inquiries and speculations can go on and have gone on in the absence of the epistemological enterprise as conceived in terms of those basic questions. Of Plato, nowhere making knowledge itself the main or even a considerable subject of investigation, and nowhere engaging in a search for the essence of knowledge. But even these meager data suffice to show that in the very dialogue in which Plato is supposed to have founded or originated epistemology, which up to that point is supposed to have been nonexistent Plato begins at the very outset by considering a theory of knowledge -- a central component of any complete epistemology that existed before he began to consider it. The same is true of the remaining two theories of knowledge, none of which was ever held by Plato or Socrates, and the third of which is expressly ascribed by Theaetetus (201C) to someone unnamed who, having made the distinction between knowledge and true judgment or opinion, also advanced just this theory that knowledge is true judgment plus an account (or explanation, or reason: in short, justification). Something very like the first theory is traceable to Heraclitus: not that knowledge is perception but that it is obtainable by perception.

Works Cited

Burnet, John Greek Philosophy: Thales to Plato (1914; reprint, London: Macmillan, 1968), 81 Russell, A History of Western Philosophy, Touchstone (1967) 73 Nicholas P. White, Plato on Knowledge and Reality ( Indianapolis: Hackett, 1976), vi

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Pharases and Its Types Remaining PartDocument16 pagesPharases and Its Types Remaining PartShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Transfer Application 71769Document1 pageTransfer Application 71769Shabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Subject Verb AgreementDocument13 pagesSubject Verb Agreementsarora_usPas encore d'évaluation

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument7 pagesScanned With CamscannerShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Phrase and Its Types: Bs English 4 Semester Concordia College Khudian Khas CampusDocument9 pagesPhrase and Its Types: Bs English 4 Semester Concordia College Khudian Khas CampusShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Syntax-Phrase Structure& Transformational Rules, Ambiguity, NP & WH MovementDocument44 pagesSyntax-Phrase Structure& Transformational Rules, Ambiguity, NP & WH MovementShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- An introduction to the functions and models of intonationDocument22 pagesAn introduction to the functions and models of intonationShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Luqman Ki NasihateinDocument17 pagesLuqman Ki NasihateinShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Quran Intro Mind Map - 220331 - 061159 - 220331 - 080514Document116 pagesQuran Intro Mind Map - 220331 - 061159 - 220331 - 080514hendra firmansyahPas encore d'évaluation

- Heads and Placement of Complements inDocument14 pagesHeads and Placement of Complements inShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- 8613 Action Research PDFDocument37 pages8613 Action Research PDFShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- 8613 Action Research PDFDocument37 pages8613 Action Research PDFShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Uncorrected Proof: Integration in Two-Way Immersion Education: Equalising Linguistic Benefits For All StudentsDocument21 pagesUncorrected Proof: Integration in Two-Way Immersion Education: Equalising Linguistic Benefits For All StudentsShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- Linguistic Segregation in Urban South Africa 1996Document12 pagesLinguistic Segregation in Urban South Africa 1996Shabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- LanguageDocument6 pagesLanguageShabana AslamPas encore d'évaluation

- 013265797X PDFDocument28 pages013265797X PDFMimi Aringo100% (1)

- MCQ For NTS Test PreparationDocument139 pagesMCQ For NTS Test PreparationShahid Mehmood86% (7)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Philosophy of Social ScienceDocument5 pagesPhilosophy of Social ScienceFraulen Joy Diaz GacusanPas encore d'évaluation

- Sf4 Lambukay Is Elem 2022-2023Document1 pageSf4 Lambukay Is Elem 2022-2023Jonas ForroPas encore d'évaluation

- Communicative Musicality - A Cornerstone For Music Therapy - Nordic Journal of Music TherapyDocument4 pagesCommunicative Musicality - A Cornerstone For Music Therapy - Nordic Journal of Music TherapymakilitaPas encore d'évaluation

- 17 Tips Taking Initiative at WorkDocument16 pages17 Tips Taking Initiative at WorkHarshraj Salvitthal100% (1)

- Final ReportDocument26 pagesFinal Reportthapa nirazanPas encore d'évaluation

- EPT Reviewer - Reading ComprehensionDocument4 pagesEPT Reviewer - Reading ComprehensionLuther Gersin CañaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mechanics For Graduate Student PresentationDocument9 pagesMechanics For Graduate Student PresentationCai04Pas encore d'évaluation

- 3 July - BSBLDR511 Student Version PDFDocument61 pages3 July - BSBLDR511 Student Version PDFPrithu YashasPas encore d'évaluation

- Mcluhan TetradDocument2 pagesMcluhan TetradJezzyl DeocarizaPas encore d'évaluation

- W Astin Implement The Strategies and Rubric - Module 4Document6 pagesW Astin Implement The Strategies and Rubric - Module 4api-325932544Pas encore d'évaluation

- Final MBBS Part I Lectures Vol I PDFDocument82 pagesFinal MBBS Part I Lectures Vol I PDFHan TunPas encore d'évaluation

- Speech About UniformDocument2 pagesSpeech About UniformMarjorie Joyce BarituaPas encore d'évaluation

- Balancing Tourism Education and Training PDFDocument8 pagesBalancing Tourism Education and Training PDFNathan KerppPas encore d'évaluation

- UNIT II Project EvaluationDocument26 pagesUNIT II Project Evaluationvinothkumar hPas encore d'évaluation

- The Veldt by Ray Bradbury: JavierDocument5 pagesThe Veldt by Ray Bradbury: Javierapi-334247362Pas encore d'évaluation

- Intelligence PDFDocument19 pagesIntelligence PDFmiji_ggPas encore d'évaluation

- Philosophical Reflection on Life's SituationsDocument2 pagesPhilosophical Reflection on Life's Situationsronald curayag100% (5)

- Reflect and Share From ExperiencesDocument3 pagesReflect and Share From ExperiencesRamos, Janica De VeraPas encore d'évaluation

- MIGDAL State in Society ApproachDocument9 pagesMIGDAL State in Society Approachetioppe100% (4)

- Strategic & Operational Plan - Hawk ElectronicsDocument20 pagesStrategic & Operational Plan - Hawk ElectronicsDevansh Rai100% (1)

- Ethics Activity BSHMDocument5 pagesEthics Activity BSHMWesley LarracocheaPas encore d'évaluation

- NCBTSDocument11 pagesNCBTSFrician Bernadette MuycoPas encore d'évaluation

- Grammar and Vocabulary Mock ExamDocument3 pagesGrammar and Vocabulary Mock ExamDorothy AnnePas encore d'évaluation

- Protection of Children: A Framework For TheDocument36 pagesProtection of Children: A Framework For TheLaine MarinPas encore d'évaluation

- Modul Q Gradder Class PDFDocument446 pagesModul Q Gradder Class PDFbudimanheryantoPas encore d'évaluation

- (Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation) Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation - Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation-Speak (L01-L90) (2021)Document383 pages(Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation) Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation - Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation-Speak (L01-L90) (2021)Ranjan SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Secret Sauce of NegotiationDocument34 pagesThe Secret Sauce of NegotiationantovnaPas encore d'évaluation

- HKIE M3 Routes To MembershipDocument25 pagesHKIE M3 Routes To Membershipcu1988Pas encore d'évaluation

- A Roadside Stand by Robert FrostDocument6 pagesA Roadside Stand by Robert FrostChandraME50% (2)

- Wisc V Interpretive Sample ReportDocument21 pagesWisc V Interpretive Sample ReportSUNIL NAYAKPas encore d'évaluation