Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

35163383

Transféré par

Atul IbrahimDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

35163383

Transféré par

Atul IbrahimDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Educational Action Research Vol. 16, No.

4, December 2008, 545555

Examining the impact of phonics intervention on secondary students reading improvement

Karen Edwards*

College of Education and Human Services, Central Michigan University, Michigan, USA (Received 13 November 2006; final version received 7 March 2008)

REAC_A_344740.sgm Taylor and Francis Ltd edwar2kL@cmich.edu KarenEdwards 0 400000December 16 Taylor 2008 & Francis Original Article 2008 0965-0792 Action Research Educational(print)/1747-5074 10.1080/09650790802445726(online)

This paper describes an action research project focusing on the effects of a phonics intervention on the reading fluency of high school students. Phonics instruction is normally associated with earlier stages of learners reading development. If it is an effective tool for early readers, then it would seem that struggling readers at the high school level might benefit from an intervention program that used a phonics-based approach. Pre-testing identified the decoding skills that students were unfamiliar with and the phonics intervention addressed the identified areas of need. Students were tested three times over time: one as a baseline measure, the second after a seven-week intervention was completed, and the last one year after the completion of the initial intervention. Two measures were recorded for each of the three time spots: the first was Raw Score and the second was Reading Grade Level. Results showed that there was a significant change over time in the three measures for both Raw Score and the Reading Grade Level. All students benefited significantly from the phonics intervention. The results of this intervention encourage the use of structured phonics with struggling high school age students as a strategy to improve their reading fluency. Keywords: phonics intervention; secondary students; reading improvement

Background In my position as the curriculum director in a small rural northern Michigan school district, I had the opportunity to work closely with the high school teaching staff and principal. The high school had approximately 300 students in grades 9 through 12 and a staff of 14 teachers. In the US students in ninth grade are typically ages 13, 14 and 15 depending on the time of the year. At the start of the school year in September students enter as 13- or 14-year-olds and exit in June as 14- or 15-year-olds. Ninety-nine percent of the districts student population was white, and 50% of the students received free and reduced lunch, which was an indication of low income. The high school students had six classes during their school day consisting of approximately 60 minutes each. Subjects for ninth graders included English, Social Studies, Science, Mathematics, Physical Education, and either Art, Music, Industrial Arts, Computers, Drafting, or a Foreign Language. There were four nine-week marking periods when students received progress reports on their learning in each of their classes. At the end of the first nine-week marking period of the school year, the principal reviewed student grades and noticed that the fifth hour ninth-grade English class had much lower grades than the other three English classes taught by the same teacher. He looked at this particular subject because it was the English teachers first year of teaching. When he saw

*Email: edwar2kL@cmich.edu

ISSN 0965-0792 print/ISSN 1747-5074 online 2008 Educational Action Research DOI: 10.1080/09650790802445726 http://www.informaworld.com

546

K. Edwards

the difference in grades between the fifth hour class and the other classes taught by the same teacher, the principal asked the teacher and me to meet with him to investigate this discrepancy. At our initial meeting, we discussed the lower grades of the fifth hour class. In this high school students attended six different classes each day. The teacher had one period for preparation and taught four sections of ninth-grade English and one Journalism class. Each day was the same schedule with the same students during the same time block. The fifth hour class was after lunch and many teachers feel that teaching students in this time block is a challenging time to engage students in learning. When students are scheduled there is consideration given to the other classes that they will take, and every teacher has a class during this time block unless it is their preparation hour. The teacher, the principal, and I brainstormed what would account for the difference in the grades of this class as compared to the other three English classes. Although these students were in fifth hour, which can be a challenging time period, the teacher felt the time period was not the problem, but the students skills were below those of other classes. The teachers learning goals in the classroom were to introduce students to interesting texts and authors. He expected students to be able to discuss and explore an authors purpose, style, message, and other English Language Arts Content Standards identified by the State of Michigan as appropriate for the grade level. Our concern was that the students in this class were not doing what was expected of good readers and the students were not able to discuss the texts studied in the class. They were not doing the assignments and even if the teacher modified the assignments and had more active activities they were not able or willing to participate in classroom discussions and activities related to the material being studied. We wondered if the problem was that the students could not read, or was the problem that the students would not read? After much discussion I volunteered to examine the curriculum files and testing information on each of the students in the class. I would additionally give each student a reading assessment and a reading interview. Data were collected from the students cumulative files or CA60s. Those data included past test scores from the statewide testing instrument, the Michigan Educational Assessment Profile (MEAP), districtwide norm-referenced testing data from the California Achievement Test (CAT), and the Pre-Stanford Achievement Test (PSAT). Data also included grades from past years and grades from the other ninth-grade English classes for the first marking period. After this information was collected and organized, we scheduled a second meeting to discuss the findings. At the second meeting, the findings from the testing and the past performances of the students were shared. Based on the data we saw two things. Firstly, the testing showed that the students as a whole were below grade level readers. Many students did not have basic decoding skills needed to sound out unknown words. Secondly, the survey showed that the students did not like to read. The students liked to listen to books, but did not want to read them. When asked what their favorite book was, they most often mentioned a book read aloud to them by their sixth-, seventh- or eighth-grade classroom teacher. After reviewing these results we talked about what we could do to address their weaknesses. If students could not read the texts, what skills and strategies did they need to learn in order to improve their reading abilities so they could read and discuss the class assignments? Would the strategy of whole class reading make a significant difference? Would small group work be the most beneficial approach? Would adding a phonics review help improve student reading skills? If they were able to read the text, would they be more interested in discussing the text? This scenario is the impetus for the action research shared in this article.

Educational Action Research

547

Action research project The research undertaken in this Action Research project involved the following question:

If struggling high school English students received a review of phonics, would this intervention improve their reading as measured by a standardized assessment tool and would improvement continue over time?

The definition of phonics used in this research was the concentrated study of the soundsymbol relationships in order to learn to read and spell. The purpose of phonics in this project was to increase accuracy of decoding and increase fluency in word recognition. The debate over the most effective method to use for early reading instruction has a long history. To assist in that debate several educators have summarized the research on early reading strategies. They have reviewed a plethora of research that identifies the teaching of phonics as an important component of early reading instruction that benefits students ability to read and write. The review of the research summarized by Jeanne Chall (1967, 1983, 1996), the Commission on Reading (Anderson 1985), and Marilyn Jager Adams (1990) confirms that emphasizing the relationship between letters and sounds resulted in better learning for students. The summary of the research continually confirmed that although reading for meaning is important and should not be ignored, the early reading approaches that emphasize phonics and the focus on decoding in early reading instruction have been shown to be more effective in helping children learn to read than those that do not emphasize phonics. In support of the importance of phonics in reading instruction the International Reading Association (IRA) wrote a Position Statement on The Role of Phonics in Reading Instruction (1997). The statement identified three assertions related to phonics and its role in reading. Phonics was identified as an important component of beginning reading instruction and the statement suggested that classroom teachers in the early grades need to be teaching phonics as part of their reading program. The statement also suggested that phonics instruction must be embedded in the context of the total reading program. This research on the importance of phonics for beginning readers influenced our decision to focus on a phonics intervention for our older students in this high school classroom. If it was important for early readers to learn phonics, and if our students as early readers did not learn some of the phonics skills, would they benefit from an intervention that taught them the phonics they missed in the earlier grades? With phonetic knowledge, our hypothesis was that the targeted high school students reading levels would improve. Additionally, phonics along with strategies such as finding roots, affixes, small words within larger words, and context clues were all tools that students should be encouraged to use when they attempt to decode an unknown word. This is not suggesting that phonics is the only or most important component of reading, but in conjunction with the reading of engaging pieces of literature and the learning of comprehension strategies it is an assist that would give students concrete strategies to decode unknown words they encounter. In view of the fact that the classroom teacher felt he had tried several different strategies and they had not made a difference, we decided a phonics intervention would be the best approach to try to improve students reading ability in this class. Other interventions could have been implemented, but we decided based on the data collected and analyzed that a phonics-based intervention was appropriate. We knew that the students had been taught phonics skills at some time in their earlier schooling, but believed they had forgotten them or had not been ready to integrate the information into their reading repertoire at the time the skill was originally taught. The phonics components taught during their high school

548

K. Edwards

intervention would be a review for many of the students and an opportunity to learn specific phonetic information they were lacking. Since I was the district curriculum director, had an office in the high school building, and had been a classroom teacher, remedial reading teacher, and reading consultant, it would be feasible for me to teach a phonics component in the form of mini-lessons in this English class. Based on my experience with struggling readers at all grade levels and based on the research supporting the use of phonics, I felt that these high school students would benefit from phonetic knowledge. Through experience working in the district with the elementary teachers, I knew that phonics skills were a part of the early reading program. The high school students in this class were from the district and so had been taught phonics in the lower grades when they were learning to read. Reviewing phonics with these students would be reintroducing them to the phonics skills they had already been introduced to in their past schooling. The lessons would be a review and we were hopeful that students would pick up and integrate the forgotten information quickly. Any new phonics information learned would be small but significant skills that the student had missed during initial instruction in previous grades. Learning these skills would add to their ability to be independent readers. Also working closely with the classroom teacher would help embed the phonics in the total reading program. Students would make use of the skills they were learning as they went about the reading tasks in their English class. In order to make this phonics knowledge useful, I knew that the content needed to be taught quickly, that the lessons needed to be fun to learn, that the students needed the opportunity to practice the skills with me, and that students needed opportunities for practice with their classroom teacher. The practice in their classroom would help the students appreciate the value of the skills they were learning, as they became more competent and capable readers. Participants The students in the fifth hour ninth-grade English class were the participants in this study. There were 16 students in the class. Eleven of the students were boys and five of the students were girls. The students ranged in age from 14 to 16 years old at the time the study began. The intervention took place in the second semester of their ninth-grade year, which was half way through the grade level. These students were the target group that received the phonics intervention because of the lower grades earned by the class members as compared to the other three ninth-grade English classes taught by the same first year teacher. Data collection and findings The Slosson Oral Reading Test (SORT) was the assessment tool used to monitor progress and identify areas of need. The SORT is a norm-referenced test that results in a Reading Grade Level score. Test results correlate highly to reading comprehension test results. It is a word-calling test with graded word lists. The greater the number of words the student can read fluently, the higher the Reading Grade Level score. The test determines each students Reading Grade Level. The Reading Grade Level is stated in years and months. For example, 5.2 Reading Grade Level means the second month of the fifth grade. The test has a reliability coefficient of .99 (test-retest interval of one week) therefore the SORT can be used at frequent intervals. The SORT was used to determine baseline data on each student so that we could later test to determine growth. An analysis of the words missed on the SORT revealed diagnostic information which was used to determine instructional content.

Educational Action Research

549

A miscue analysis resulted in the following findings: when reading words from the word list most students did not know how to sound these endings /ance/, /ine/, /ion/, /ous/, /ious/, /que/, /ence/, /ment/. Students did not know when the c and g were sounded either hard or soft. Data showed us that students did not know the sounds associated with vowel combinations (vowel diphthongs and diagraphs) /ai/, /ay/, /au/, /aw/, /augh/, /ei/, /eigh/, /ey/, /eu/, /ew/, /eau/, /ea/, /ie/, /y/, /oo/, /oe/, /oi/, /oy/, /ou/, /ow/, /ough/, /ui/, /ue/. They did not know the sounds consonant teams made. The assessments also showed that students did not know how to break down a larger word into syllables or how to sound the vowel in a syllable based on the type of syllable. Additionally, when taking the SORT, it was evident that students did not practice many basic reading skills. Most students did not track to the end of the word before determining a word. They saw the beginning letter and guessed at any word that might start with the initial letter. Students did not know to look for known words within a larger word or to look for a base word. The diagnostic information gained from the SORT confirmed that students had little knowledge about what to do when they came to an unknown word. In addition to the SORT, a reading attitude interview was given to the students. The oneon-one interview included the following questions: Do you usually read the class assignments? Do you think you are a good reader? Do you like reading? When is the last time you read a book for pleasure? What is your favorite book and why did you choose it? The interview questions were summarized and revealed some interesting information about their reading habits. Most students were not reading their assignments. The students did not consider themselves to be good readers, did not like to read, and were not reading on their own for pleasure. When asked about their favorite book and why they chose it, most students identified their favorite book was one read aloud to them by a sixth-, seventh- or eight-grade teacher. They commented that they liked the teachers oral interpretation of the different characters and use of voice to emphasize actions taking place in the book. In American schools in first grade through eighth grade a popular practice is a daily teacher Read Aloud time of about 10 to 20 minutes. The book read aloud by the teacher during this Read Aloud time was the one most students mentioned as their favorite book. With information about their interests from the interview questions and the analysis of their areas of need from the SORT we thought about the following questions. What was the best teaching plan going to be to address their deficits? How would the instructional plan be implemented? What was a reasonable improvement goal? Action plan As the intervention plan evolved I worked closely with the classroom teacher. We determined that phonics lessons would be done in the classroom three times per week during the first 15 minutes of the class period. We planned on the intervention lasting seven weeks. Teaching small increments and giving students time between sessions to integrate the information and to practice in class with the teacher was our intent. The content taught would relate directly to the assessment data analyzed on the SORT. At the end of the seven weeks, we would again test the students. Our goal was a gain of half a grade level on the reading assessment. That would mean that each student would read correctly and fluently 10 additional words on the SORT. On the first day of the phonics intervention I went into the classroom and explained what we were going to do and why we were doing it. I shared with students what the testing results revealed, and that they were going to learn some strategies to help them be successful readers. To motivate the students we told them that we were going to ask their opinions of

550

K. Edwards

the project when the intervention was finished to determine if they thought it was an effective process that would benefit others. Each student was given an individual notebook with all the supplies needed for activities during the project. The notebook was referred to it as their Tool Kit or Tip Kit. This kit included a three-ringed notebook, paper, dividers, pencil case, pencil, pen, highlighter, file card, and post-it notes. The students were told that they would practice the things learned in the mini-class with their regular teacher. The most important thing we wanted these students to know was that we were going to be reviewing many things about reading that they had heard before, but based on the testing many of them did not remember how or when to use that knowledge. If the mini-lesson information was new information or clarified something for them they should grab the new information or the tip and add it to their knowledge of reading. I shared that we knew from their testing that they were smart people and just had some phonics pieces that they needed to add to their conscious level so they could purposely use that information to improve their reading fluency. If they were reading the words correctly and fluently, it would improve their comprehension level. This improved ability would make reading in their English class and their other classes easier. After the stage was set for the use of the Tool Kit or Tip Kit, students designed a nametag using the large file card in their Tool Kit. They were asked to print their name on the card and to draw a picture of their favorite book, a favorite place to read, and a tip about reading that they would share with the class. As students introduced themselves to me, we determined how many syllables were in their name and how to decide how many syllables were in any word. The tip was that a syllable is a group of letters with at least one vowel. We reviewed the vowel names with a chant to make it fun. I shared the tip that the easiest and quickest way to determine the number of syllables in a word they were saying, was to touch their chin with their fingertips and count the movements as they pronounced the word. Each movement was a syllable. The syllable that dropped the most was the accented syllable (another tip). After the introductions, I gave the students a fun and easy pretest. We started the intervention sessions in a motivating way and imbedded some phonics information in the initial activity. It was a positive beginning that continued throughout the seven weeks. The mini-lessons continued to review the basic components of a systematic phonics program. Each new component was embedded in activities so students were using and practicing the information in an enjoyable way. With the practice provided during the lessons students quickly acquired the new skills. Some of the first things we reviewed were how many letters were in the alphabet. Most of the students had never thought about the number of letters in the alphabet. Once they knew there were 26 letters, they could always retrieve that information. They were surprised to know that there were 44 sounds. Knowing there were 44 sounds helped them understand that in order to read, they had to know what letter combinations made those 44 sounds. Students practiced the alphabet sounds and the combinations. They moved on to the vowels and reviewed all the sounds they make. Students practiced the sounds of all the vowels and vowel combinations. The use of charts and chants avoided boredom. To move this knowledge to texts students searched for words in their books that were examples of the vowel combinations and decoded the words. They learned how to break down or divide a large word into syllables and then how to sound the vowel within the syllables. This skill gave students a powerful tool. Instead of being stuck on a big word that they had no idea how to say, they now had a strategy to break down the word into smaller parts. Another strategy we focused on was tracking through the entire word, breaking the word into syllables, and thinking about what word would make sense in the sentence before saying it. We continued learning and practicing skills identified from the pretest data.

Educational Action Research

551

Moving the learning from isolated skills to real text was important for students so they could practice the skills during the act of reading. Using real text to practice decoding large words was helpful. Teams of students tried to stump each other by finding words that were difficult. Eventually students began reading pieces of text. First the students would practice reading the text by themselves, then with a partner, and then volunteers would read out loud. They loved being successful and showing others in the class how well they read. Another motivating strategy was to have students work with a partner to practice reading a selection. One student would read while a second student would use a stop watch to time how long it took to read a chosen paragraph. Each reading took less time and was read with greater fluency. As students became more skilled they began reading short plays and each person practiced their part and then the play was shared with the class. By the end of the sevenweek intervention students were using their new knowledge and confidence in the act of reading real text. Results The SORT was the instrument used for each of the three assessments: one as a baseline measure, the second after the seven-week intervention was completed, and the third was one year after the completion of the initial intervention. The SORT has 200 words on the assessment. The students Raw Score was used to establish their Reading Grade Level. The Raw Score was the number of words the student reads fluently and correctly. Dividing the Raw Score in half established the students Reading Grade Level. For example, if the Raw Score was 184, half of that number would be 92. The Reading Grade Level would be 9.2 or the second month of ninth grade. A student with a score of 200 would have a perfect test and would score a 10.0 Reading Grade Level or tenth grade. Being on grade level at the time of the original testing would have been 9.5. Students #5, #12, and #14 had scores that were closest to grade level. Our initial goal was an improvement of half a year and that goal was met and exceeded. Students had increased an average of 1.1 grade level in seven weeks. Individually the greatest increase was three grade levels. This was very rewarding data. The classroom teacher shared that he had learned many phonics tips and students were using the tips during class. I met individually with each student to share both their initial score and their new score as evidence of their hard work and learning. I asked them if they felt better about their reading abilities. They all reported that they thought the Tool Kit and phonics tips were helpful. For our third data point we tested students again at the one-year anniversary of the initial intervention. They were now in their second semester of their tenth-grade year. What we saw was that improvement continued. Again, I met with each student individually to share the testing results. Each was delighted with their results. Students self-reported they liked reading better and they had been doing some reading for pleasure. They also indicated they felt more confident and felt they had the skills to break down an unknown word into its parts so that they could then combine context clues in the text to determine the unknown word. Usually, if the unknown word was in their speaking vocabulary, they were able to determine the word. This added to their comprehension and they were feeling very confident about their reading ability. See Table 1. Table 1 summarizes the results of the data. It includes the baseline test scores, the scores after seven weeks of phonics intervention, and the scores one year later. The data showed that student scores did not regress, and all student scores continued to improve. This was an indicator that the phonics information had remained with the students

552

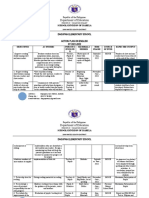

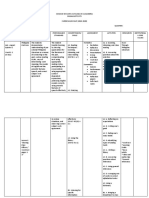

Table 1. Testing data growth at three data points. Data Collection II (after seven week intervention was completed) Two Month Grade Level Gain One Year Raw Score One Year Grade Level Growth after seven-weeks of phonics intervention Data Collection III (one year after completion of initial intervention) Growth one year after completion of intervention

K. Edwards

9th grade English Class

Data Collection I (prior to implementation of phonics intervention)

Name

Baseline Raw Score

Baseline Grade Level

Two Month Raw Score

Two Month Two Month Raw Score Grade Level Gain

Total Raw Score Gain

Total Grade Level Gain

#1 91 #2 118 #3 114 #4 155 #5 192 #6 132 #7 173 #8 173 #9 107 #10 175 #11 153 #12 189 #13 164 #14 187 #15 153 #16 157 AVERAGE 2433/16=152.1

4.5 113 5.6 22 1.1 151 7.5 60 3.0 5.9 128 6.4 10 0.5 162 8.1 44 2.2 5.7 174 8.7 60 3.0 186 9.3 72 3.6 7.7 174 8.7 19 1.0 184 9.2 29 1.5 9.6 197 9.8 5 0.2 200 10.0 8 0.4 6.6 157 7.8 25 1.2 169 8.4 37 1.8 8.6 195 9.7 22 1.1 200 10.0 27 1.4 8.6 183 9.1 10 0.5 190 9.5 17 0.9 5.3 153 7.6 46 2.3 161 8.0 54 2.7 8.7 191 9.5 16 0.8 191 9.5 16 0.8 7.6 177 8.8 24 1.2 187 9.3 34 1.7 9.4 191 9.5 2 0.1 197 9.8 8 0.4 8.2 188 9.4 24 1.2 195 9.7 31 1.5 9.3 196 9.8 9 0.5 200 10.0 13 0.7 7.6 176 8.8 23 1.2 196 9.8 43 2.2 7.8 185 9.2 28 1.4 190 9.5 33 1.7 121.1/16=7.6 2778/16=173.6 138.4/16=8.7 345/16=21.6 17.3/16=1.1 2959/16=184.9 147.6/16=9.2 526/16=32.9 26.5/16=1.6

Educational Action Research

553

and the reading scores reflected the continued use of their new knowledge. The students with the lowest scores of 4.5, 5.3, 5.7, and 5.9 were also the students with the most growth 3.0, 2.7, 3.6, and 2.2. Although other learning events happened to these students during the year and may have had an impact on their success on this test, we are proposing that the seven-week phonics intervention made the difference. Statistical significance In this study we were trying to test the effect of the implementation of phonics intervention on students that had reading difficulty. Students were tested three times over time: one as a baseline measure, the second after seven weeks of intervention was completed, and the last one was one year after completion of initial intervention. Data contain 16 students, five female and 11 males. Two measures were recorded for each of the three time spots: the first was Raw Score; the second was the Reading Grade Level. The Raw Score variable is a linear function of the Reading Grade Level variable. A general linear model was conducted twice using repeated measures analysis in SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences). Results showed that there was a significant change over time in the three measures for both the Raw Score and the Reading Grade Level and that reading growth was significant. Results showed that gender was not significant between subjects variables in both Raw Score and the Grade Level. Reflection The data were powerful indicators that the phonics intervention was effective. The continued growth seen at the one-year anniversary showed that students continued to show improvement even after the intervention was completed and no additional phonics instruction took place. I attribute the continued growth to the possibility that the more students used the new phonics tips, the easier it was to read. The easier it was for students to read, the more they read because they were having success. The more they felt success, the more they read, and the better they became at reading. The one-year data indicated that the students had the reading skills needed to read materials written at their grade level. The phonics intervention made a significant difference in their reading fluency. Upon conclusion of this project and in thinking about future projects, if this action research were to be repeated, I would collect data on student grades in their English class and their other academic classes. I would want to see if their grades improved. If their grades had improved would that indicate that the students improved reading ability affected their classroom performance? Discussion and conclusion The results of this study indicate that high school students can benefit from a short intensive phonics intervention. The most significant finding was that all students benefited from the intervention and the improvement continued over time. The improvements were significant for all students in the study. If educators know that an intervention can benefit struggling high school age readers, then it is our responsibility to give these students the tools they need for success. The high school years are the last time students have the opportunity to be given the tools to improve their reading through the formal educational process. It would be prudent to identify those students who would benefit from a phonics review and to give them that needed boost in knowledge. If the lowest fourth of the student population were

554

K. Edwards

identified and supported, could their potential for success be affected? There is no single magic intervention program that would fix all students, but if there is not the effort to assist students reading skills while in school, students will probably never get the help needed to improve their ability to read fluently. Once the student can read the words, the classroom teacher has the opportunity to focus on comprehension strategies. Upon seeing the improved scores and the improved class participation after the sevenweek intervention, the teacher and I were anxious to share the results of this project with the principal and the rest of the buildings teachers. At a staff meeting in May of the intervention year, the classroom teacher and I presented an overview of the seven-week project along with the pre-testing and post-testing data. The teacher shared that students were more engaged in the lessons which resulted in better grades. He stated that he had learned many new skills during the mini-lessons and that he was able to use these skills with students to assist them as they became more skilled readers. He shared that as a teacher he was an excellent reader and had not thought about what specific skills students needed to know to help them decode words. Learning the skills with the students helped him see how the skills helped the students to be better readers. He felt the learning skills with the students gave him knowledge of their usefulness as he saw how the learning impacted their reading ability. He also practiced the new skills with his students during regular class time. He felt that the students knew he was learning with them and then practicing the new skills with them. The students knew he wanted them to be successful and these skills were some of the tools to help with that success. He shared that not only was he using the skills with his current students, but that they would be skills that he would share with future students. The staff saw his joy that he was now able to focus on comprehension and other content area objectives with his students. The students were reading assignments and engaging productively in the class discussions. The staff was impressed with the findings from this project. When names of the students in this class were shared with the staff, comments from teachers included observations that they had seen a difference in some of the students work, and they had seen improved behavior of some of these students in their classrooms. Teachers wondered if the phonics intervention would continue. If it were to continue, what students would benefit the most from this support? How would the students be identified? What format could be used to teach the components? The teachers wondered if students who were struggling in reading should be identified and then grouped for a phonics intervention class. In other words, this project could be something done with all struggling ninth graders as they began their high school experience. These were all good thoughts that we were glad to hear mentioned. Because several teachers were interested in learning some of the most useful phonics skills that would help students we did do a phonics workshop with high school teachers at the beginning of the next school year. The teachers were receptive and reported that they put some of this knowledge to use with their students. No specific phonics intervention program was implemented for identified struggling students. Although no program was implemented, I did feel that the workshop was useful and that teachers learned some of the phonics skills that could benefit students when they came to an unknown word. I also felt that when all teachers were willing to learn and implement some of the phonics skills, that they were not leaving the job to some special program that was there to fix the struggling readers, but were willing to be a part of the solution to help students. In an effort to additionally share the information with other teachers, the following spring the action research project and results were shared at a statewide reading conference. At that time all three data points were available and these data added strength to the project as the target students continued to significantly improve in reading. Many teachers at that

Educational Action Research

555

conference were interested in this type of project and hopefully have implemented some type of support program in their buildings. In many districts throughout the US struggling readers in grades 1 through 8 are identified and given additional support including phonics, but few high schools have determined this need or implemented any such support program. This is disappointing given the research support for such a program that can make a difference for struggling students. This action research project was an example that had positive effects on student reading levels. A phonics intervention should be considered when secondary age students are reading below grade level. It is especially effective for the lowest performing students as they had the greatest grade level growth. With improved skills students have the opportunities afforded the more successful readers in our schools. A phonics intervention may not be the total answer to student reading problems, but it will give students additional skills and tools to use. Our job as teachers is to help students. We are remiss if we ignore this way of redressing inequality of achievement. Some may argue that just because students can read the words, does not mean they comprehend the text. I agree, however, if students cannot read the words, they definitely cannot comprehend the meaning of a passage. It is the responsibility of the educational community to give students the tools they need to be successful. This research suggests that older students who are not reading fluently would benefit from an intensive phonics intervention. References

Adams, M.J. 1990. Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge: MIT Press. Anderson, R.E. 1985. Becoming a nation of readers: The report of the commission on reading. Washington, DC: National Institute of Education, US Department of Education. Chall, J.S. 1996. Learning to read: The great debate. 3rd ed. San Diego: Harcourt Brace. Chall, J.S. 1967, 1983. Learning to read: The great debate. New York: McGraw-Hill. International Reading Association. 1997. The role of phonics in reading instruction: A position statement. Newark, Delaware: IRI.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- Year 4 Cefr SK Week 2Document23 pagesYear 4 Cefr SK Week 2Hairmanb BustPas encore d'évaluation

- Unlock 3 Reading and Writing TB PDFDocument145 pagesUnlock 3 Reading and Writing TB PDFBeto GuerreroPas encore d'évaluation

- Decoding and Encoding PPT With AssessmentDocument33 pagesDecoding and Encoding PPT With Assessmentmico collegePas encore d'évaluation

- 1° Ingles Workbook PDFDocument19 pages1° Ingles Workbook PDFDavid Henostroza ShuanPas encore d'évaluation

- 30545-Wiley Et Al. (2016) - Improving Metacomprehension Accuracy in An Undergrad Course ContextDocument13 pages30545-Wiley Et Al. (2016) - Improving Metacomprehension Accuracy in An Undergrad Course ContextPhilip SewePas encore d'évaluation

- Factors Related To The Students' Performance in English-Science-MathematicsDocument11 pagesFactors Related To The Students' Performance in English-Science-MathematicsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalPas encore d'évaluation

- RRL From AbstractDocument3 pagesRRL From AbstractKimberley Sicat BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 3: Pet Show: SK Tanjung Bundung YBB6307Document5 pagesUnit 3: Pet Show: SK Tanjung Bundung YBB6307Deborah HopkinsPas encore d'évaluation

- 4 5985760379857276521 unlocked-مفتوحDocument296 pages4 5985760379857276521 unlocked-مفتوحMahmoudAliPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching Reading Comprehension On Narrative Text Using Numbered Heads Together StrategyDocument26 pagesTeaching Reading Comprehension On Narrative Text Using Numbered Heads Together Strategynetti afrinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading and Writing Skills: Quarter 3Document6 pagesReading and Writing Skills: Quarter 3Mariel LognasinPas encore d'évaluation

- Edtpa Lessons WordDocument9 pagesEdtpa Lessons Wordapi-354507459Pas encore d'évaluation

- Week 4 4th Grading EnglishDocument5 pagesWeek 4 4th Grading Englishjoangeg5Pas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Contest Memo Action PlanDocument12 pagesReading Contest Memo Action PlanAnaliza Marcos AbalosPas encore d'évaluation

- PBD Transit Form With Descriptors - Year 2Document17 pagesPBD Transit Form With Descriptors - Year 2Dhaiful IkramPas encore d'évaluation

- Children Report Card CommentsDocument2 pagesChildren Report Card CommentsMohammad Aurangzeb100% (12)

- Rising+On+Air SS Literacy Lesson+4.2Document16 pagesRising+On+Air SS Literacy Lesson+4.2KENZIE LITTLESPas encore d'évaluation

- Map 19 20Document22 pagesMap 19 20Ahn Ji AhmorhaduPas encore d'évaluation

- Reading Comprehension VDocument10 pagesReading Comprehension VKanaya RafithaPas encore d'évaluation

- August 26, 2022Document8 pagesAugust 26, 2022Annabelle AngelesPas encore d'évaluation

- NEW UGE 1 Practice Set Worksheet 3making InferenceDocument11 pagesNEW UGE 1 Practice Set Worksheet 3making InferenceALBERT ALGONESPas encore d'évaluation

- Feminist Interpretation of CathedralDocument20 pagesFeminist Interpretation of CathedralcobbledikPas encore d'évaluation

- 3 Methods For Teaching ReadingDocument7 pages3 Methods For Teaching ReadingAin Najihah ASPas encore d'évaluation

- SIP Presentation - RRMDocument39 pagesSIP Presentation - RRMJayvan BarandinoPas encore d'évaluation

- NSE English10 LessonsLearnedDocument82 pagesNSE English10 LessonsLearnedjoshPas encore d'évaluation

- Teaching English in The Elementary Grades (Language Arts) Your GoalsDocument16 pagesTeaching English in The Elementary Grades (Language Arts) Your Goalsjade tagab100% (3)

- RPT Bi Year 3 2023 2024Document13 pagesRPT Bi Year 3 2023 2024TDENE HOW JIATYENN MoePas encore d'évaluation

- RPT English Form 1Document11 pagesRPT English Form 1lizaPas encore d'évaluation

- Proiectare Unități Clasa A II-a ArtKlettDocument13 pagesProiectare Unități Clasa A II-a ArtKlettIONESCU ADRIANA100% (1)

- Summer Reading Packets For Elementary Students - 2016 PDFDocument18 pagesSummer Reading Packets For Elementary Students - 2016 PDFMA W.Pas encore d'évaluation