Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Nike Zeus

Transféré par

Paul Kent Polter100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

399 vues24 pagesThis pamphlet is intended to acquaint readers with the history of the Nike Zeus Project. It was the u.s. Army's frst effort to develop an antiballistic missile (ABM) system. Despite technical and operational shortcomings, it was instrumental in establishing the foundations for its successor, the Nike-X Project.

Description originale:

Titre original

Nike-Zeus

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentThis pamphlet is intended to acquaint readers with the history of the Nike Zeus Project. It was the u.s. Army's frst effort to develop an antiballistic missile (ABM) system. Despite technical and operational shortcomings, it was instrumental in establishing the foundations for its successor, the Nike-X Project.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

100%(1)100% ont trouvé ce document utile (1 vote)

399 vues24 pagesNike Zeus

Transféré par

Paul Kent PolterThis pamphlet is intended to acquaint readers with the history of the Nike Zeus Project. It was the u.s. Army's frst effort to develop an antiballistic missile (ABM) system. Despite technical and operational shortcomings, it was instrumental in establishing the foundations for its successor, the Nike-X Project.

Droits d'auteur :

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formats disponibles

Téléchargez comme PDF, TXT ou lisez en ligne sur Scribd

Vous êtes sur la page 1sur 24

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A.

Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

Approved for Public release 09-MDA-4885 (20 OCT 09)

S

T

R

A

T

E

G

I

C

D

E

FEN

S

E

I

N

I

T

I

A

T

I

V

E

D

E

P

A

R

T

M

E

NT OF

D

E

F

E

N

S

E

*

*

*

Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO)

1984 1994

B

A

L

L

I

S

T

I

C

M

ISSI L

E

D

E

F

E

N

S

E

D

E

P

A

R

T

M

E

N

T O

F

D

E

F

E

N

S

E

M

I

S

S

I

L

E

D

E

FENS

E

A

G

E

N

C

Y

D

E

P

A

R

T

M

E

NT OF

D

E

F

E

N

S

E

Missile Defense Agency (MDA)

Established January 2, 2002

Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO)

1994 2002

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

FOREWORD

The mission of the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) History

Offce is to document the offcial history of Americas missile

defense programs and to provide historical support to the MDA

Director and MDA staff.

This pamphlet is intended to acquaint readers with the history

of the Nike Zeus Project, the U.S. Armys frst effort to develop

an antiballistic missile (ABM) system that could intercept

intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). This pioneering effort

was ambitious and controversial. The groundbreaking Nike Zeus

Project demonstrated the possibility of intercepting an ICBM, but

suffered from technical and operational shortcomings that made it

impractical to deploy. Despite these shortcomings, the Nike Zeus

Project was instrumental in establishing the foundations for its

successor, the Nike-X Project, a more robust ballistic missile defense

system.

Constructive comments and suggestions from readers are

welcome. Please forward them to Dr. Lawrence M. Kaplan, MDA

Historian, at Lawrence.Kaplan@mda.mil, or by telephone at (703)

882-6546.

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

1

As the Cold War unfolded following World

War II, America determined

that it faced a hostile and

expansionist Soviet Union.

The growing threat of Soviet

long-range aircraft and

long-range missiles posed

an unprecedented challenge

to defending America against

attack. In response, the policies

of containment and deterrence became the cornerstones of American

strategic doctrine, with a heavy reliance on nuclear weapons and

strategic air power to discourage any Soviet or Soviet-supported

military aggression. During the Eisenhower administration this

policy of striking back decisively against any aggressor was known as

massive retaliation and evolved into the policy known as mutual

assured destruction or MAD in the Kennedy administration. By the

early 1960s, the advent of long-range Air Force ballistic missiles and

Navy submarine-launched ballistic missiles joined manned bombers

in completing Americas strategic deterrent triad.

Although deterrence relied primarily on offensive measures,

strategic missile defense (defending the continental United States)

became an increasingly desirable adjunct to American strategic

capabilities. Following World War II, the Air Forces Project Wizard

began developing a strategic antiballistic missile (ABM) system and

in the early 1950s the Army began developing

a theater ABM system, Project Plato, to protect

deployed military forces against short-range

ballistic missiles. During this period, however,

the Army was at a signifcant disadvantage when

competing for annual budget money with the

other services since it did not have a strategic

offensive mission. In 1955, this situation

began changing after intelligence reports of an

Project

Wizard

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

2

impending Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) threat

spurred the Department of Defense (DoD) to launch several high-

priority offensive missile programs among the services. These

competing missile programs, which were intended to achieve early

operational capabilities, blurred distinctions between the services

roles and missions. In this environment the Army sought to compete

with Project Wizard for a role in strategic missile defense.

In March 1955, as part of its air defense

research, the Army commissioned Bell

Telephone Laboratories, the research and

development branch of the Western Electric

Company, to examine the prospects for

developing a strategic ABM system. Bell

Labs had developed the frst generation non-

nuclear Nike I (Ajax) antiaircraft surface-

to-air missile (SAM) and was developing a

second generation nuclear-armed Nike B

(Hercules) SAM.

Bell Labs conducted an 18 month Nike II feasibility study that

examined continental United States air defense requirements for the

1960s against both high-performance air-breathing threats and long-

range ballistic missiles. Initially, the study explored the possibility

of a common antiaircraft defense system covering all high-altitude

threats, which employed a missile with different warheads, one for

use against missiles and one for use against

aircraft. In June 1955, as concern increased

over the ICBM threat, the Army requested the

study shift its focus primarily to missile defense.

The shift coincided with General Maxwell D.

Taylors appointment as Army Chief of Staff.

He aggressively sought to increase the Armys

share of the budget and became a staunch

Hercules

AJAX

Taylor

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

3

advocate for expanding the Armys air defense role into strategic

missile defense.

The Nike II study assumed that a precisely guided nuclear

warhead would be necessary to ensure successful interception of

a ballistic missile. By comparison to World War II air defense

objectives, where a 10 to 15 percent attrition rate was acceptable

against aircraft, the nuclear ballistic missile threat required defense

levels of 95 to 100 percent attrition against hard to kill reentry

vehicles. Studies showed that using a 50 kiloton nuclear warhead in

the interceptor missile required relatively small miss distances to kill

an enemy warhead, and the use of a high-yield defensive warhead

did not reduce the need for a guidance system of high accuracy.

The frst question addressed was where

in the attacking missiles trajectorythe

boost, midcourse, or terminal phasean

intercept should take place. Given the

limited information collection capabilities

against hostile missile launches, the study

assessed the midcourse intercept option

too diffcult to be feasible and proposed

a terminal-phase interceptor in its place.

Technological limitations suggested that

a homing system would be unworkable

for the interceptor and the most attractive

guidance method would be one based on

the Nike Ajax/Nike Hercules command

systems.

The study recognized that an extensive communications network,

integrating detection, acquisition, tracking and launch control

radars, data processing, computation, and tactical control would

be necessary to make the system work. All of these disparate parts

would have to work together very rapidly as an integrated whole.

Ballistic

Trajectory

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

4

Given limited warning times of 10 to 15 minutes for a missile attack,

most actions had to be semiautomated. A human operator would

only be able to veto a programmed launch.

The challenge of discriminating real warheads from a debris

cloud and other radar countermeasures posed a signifcant problem.

The study recognized that high rates of ICBMs arriving over their

targets, coupled with the diffculty of discriminating decoys from

real warheads, would require a system capable of engaging up to 20

targets per minute.

In January 1956, Bell Labs advised the Army that a long-range,

high-data-rate acquisition radar would be an essential component of

any ballistic missile defense system. Bell Labs also advised that if

development of this vital radar could begin immediately, an interim

ABM defense might be possible with the developmental Nike B

(Hercules) missile system.

Bell Labs subsequently completed 50,000 analog computer

simulation intercepts of ballistic missile targets. These simulations

indicated that it was possible to intercept a target fying through

space at 24,000 feet per second. Bell Labs presented their fndings

to the Army in October 1956.

In November 1956, Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson

attempted to disentangle Army and Air Force air defense

responsibilities by distinguishing between area and point defense.

The frst, assigned to the Air Force, involved the

concept of locating defense units to intercept

enemy attacks remote from and without

reference to individual vital installations,

industrial complexes or population centers.

Point defense, an Army responsibility, was the

defense of specifed geographical areas, cities

and vital installations. Air defense missiles

Wilson

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

5

designed for point defense were to be limited to horizontal ranges

of approximately one hundred nautical miles. Even so, it was not

easy to draw a clear distinction between area and point defense, and

a rivalry grew between the Army and Air Force as they developed

competing air defense missiles.

In February 1957, the Army initiated the Nike II development

program with Western Electric as the prime

contractor, and Bell Labs and the Douglas

Aircraft Company as subcontractors, and

changed the name to the Nike Zeus Project.

The contract laid out a six-year development

program for the Nike Zeus antimissile missile

system under the supervision of the Army

Rocket and Guided Missile Agency, an element

of the Army Ordnance Missile Command at

Redstone Arsenal, Alabama. Bell Labs served as

the technical project director while the Douglas

Aircraft Company undertook development of

the nuclear-capable Zeus exoatmospheric (outside the atmosphere)

interceptor, which represented the third generation in the Nike air

defense guided missile family. Zeus was intended to be part of an

integrated ABM defense system that included advanced radars for

acquisition and tracking, and battle management communications

equipment, which the Nike II study indicated would be necessary.

The Army also intended to draw upon

Project Platos development in furthering

the Nike Zeus Project.

Technical challenges abounded in

the Nike Zeus Project because so much

of the developmental work done was

groundbreaking. The proposed missile

design, the design architecture of the

systems radars, the computer and

Zeus (A-Model)

Nike Zeus

Project Offce

Emblem

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

6

communications integration, and even fnding adequate ranges for

testing, had to be developed from the ground up. From the outset

these technical challenges and projected high costs made Nike Zeus

a continuing target of criticism, particularly from the Air Force and

the scientifc community.

In the midst of this growing controversy, the Soviet Union

announced a successful test fight of an SS-

16 ICBM in August 1957; and on October

4, 1957, the Soviets launched Sputnik, the

worlds frst artifcial satellite. These catalytic

events heightened concerns about American

vulnerabilities to a Soviet ICBM attack

and created a political environment more

supportive of developing and felding an ABM

system.

A few weeks after the Sputnik launch, the

Army stood frm in pressing for Nike Zeus development. General

Taylor advised Congress:

We can see no reason why the country cannot have an

antimissile defense for a price which is within reach. I am

sure many of you have heard the statement that the dollar

requirements for this kind of defense are astronomical and

that the whole concept is beyond consideration. I can assure

you that the studies which I have seen lead

me to a different conclusion. We can have an

antimissile defense.

In early November 1957, the presidentially

appointed Gaither Panel (named after its chairman,

H. Rowan Gaither, Jr., then chairman of the

board of directors of the Ford Foundation and a

founder of the RAND Corporation), submitted its

Sputnik

Gaither

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

7

report on continental defense,

Deterrence & Survival in

the Nuclear Age, to the

Eisenhower administration.

The report assigned the highest

priority to protecting the nations primary deterrent, Strategic Air

Command (SAC) bombers, from a surprise Soviet attack, and

recommended having active missile

defense at SAC bases. This included

developing radars capable of providing

early warning of missile attacks, hardening

radars against countermeasures, and

employing interim antimissile defenses

using available weapons such as the Nike

Hercules and land-based versions of the

Navys Talos air defense missile. The

report also recognized the importance of

protecting cities and other key targets:

[T]he importance of providing active defense of cities or

other critical areas demands the development and installation

of the basic elements of a [missile defense] system at an

early date. Such a system initially may have only a relatively

low-altitude intercept capability, but would provide the

framework on which to add improvements brought forth by

the research and test programs.

By early 1958, the Army and Air Force

rivalry over dominance of the strategic

missile defense program prompted Secretary

of Defense Neil H. McElroy to settle the

dispute. On January 16, 1958, he assigned the

active strategic defense mission to the Army.

Later that month, the Nike Zeus Project

received additional support from a National

B-52

McElroy

Hercules Talos

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

8

Security Council position paper (NSC 5802)

on continental defense that called for an

anti-ICBM weapons system as a matter of the

highest national priority.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff argued for an

administration commitment to accelerate

Nike Zeus development, but President Dwight

D. Eisenhowers defense secretaries, Neil

H. McElroy (1957-59) and Thomas S. Gates

(1959-61), along with many in the scientifc

community, were not convinced the program

was worth the cost and effort to rush to an

early deployment. President Eisenhower also

was skeptical, questioning whether an effective

ABM system could be developed in the 1960s.

The same attitude continued into the Kennedy

administration (1961-63).

The Armys preliminary deployment

studies reportedly estimated that 60 Nike Zeus

batteries, each armed with 50 interceptors,

would be suffcient to protect major cities and

major military installations and would cost

approximately $10 billion. The costs rose to

approximately $15 billion for 120 Zeus batteries

offering expanded coverage to urban centers

with populations larger than 100,000 and major

industrial targets.

President John F. Kennedy took a keen interest in Nike Zeus

development. In pondering why Nike Zeus was so controversial

among scientists, he once commented to Dr. Jerome Wiesner, his

Science Advisor: I dont understand. Scientists are supposed to be

rational people. How can there be such differences on a technical

Eisenhower

Gates

Zeus

(B-Model)

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

9

issue? He was particularly concerned about the systems viability

in the face of mounting pressure for its deployment. Dr. Wiesner

explained:

In 1961, when President Kennedy frst

began to survey his military problems, his

attention was drawn forcefully to an anti-

missile system, the Nike-Zeus. He began

to get a food of mail, from friends, from

Congress, from people in industry. The

press pointedly questioned him about his

plans to deploy the Nike-Zeus system. He

began to see full pages for it in popular

magazines like Life and Saturday Evening

Post, proclaiming how Nike-Zeus would

defend America and listing the industrial

towns that would proft from the contracts

for it. This pressure built up to the point

where President Kennedy came to feel that

the only thing anybody in the country was

concerned about was the Nike-Zeus. He

began to collect Nike-Zeus material. In one

corner of a room he had a pile of literature and letters and

other materials on the subject. He set out to make himself

an expert on the Nike-Zeus and spent hundreds of hours

gathering views from the scientifc community about it.

As with any groundbreaking

system in development, the

early Nike Zeus test results

were mixed. Though the radar

and communications systems

progressed reasonably well,

many early test frings of the

missile failed in part due to

Wiesner

Kennedy

Zeus Intercept Test

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

10

design faws. Refnements in the missile design and other system

components continued and in late 1961 a Zeus missile supported by

all of its associated system components successfully intercepted a

Nike Hercules target missile at White Sands Missile Range, New

Mexico. In early 1962, the Army transported the entire system to

the Kwajalein Missile Range in the Marshall Islands and began

conducting a series of Zeus tests against live ICBM targets with the

following results:

Mission

Number Date Target Remarks

K1 6-26-62 Atlas D Failure

K2 7-19-62 Atlas D Partial Success

K6 12-12-62 Atlas D Success (frst missile in salvo)

K7 12-22-62 Atlas D Success (frst missile in salvo)

K8 2-13-63 Atlas D Partial Success

K10 2-28-63 Atlas D Partial Success

K17 3-30-63 Titan I Success

K21 4-13-63 Titan I Success

K15 6-12-63 Atlas D Success

K23 7-4-63 Atlas E Success

K26 8-15-63 Titan I Success

K28 8-24-63 Atlas E Success

K24 11-14-63 Titan I Success

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

Although the test program showed promise in 1962, DoD

decided not to proceed further with Nike Zeus development. Nike

Zeus had too many technical and operational shortcomings to

warrant continuation. Dr. Wiesner explained:

[T]here were several things wrong about the Nike-

Zeus that would have made it relatively ineffective in real

situations. First, as originally designed, it was supposed

to intercept incoming missiles at very high altitudes, out

of the atmosphere. This meant that it was easily confused;

an enemy could mix real nuclear missiles with lightweight

decoys made to look like missiles and send them in against

Nike-Zeus, so that it would be totally saturated. To correct

this we allowed the incoming devices to come down into

the atmosphere; the difference in weights allowed the heavy

pieces, the real warheads, to go on, while all this other

lightweight decoy junk was slowed down and separated out.

This tended to work somewhat better, but even so, the whole

system as conceived really wasnt good enough. It could

not respond fast enough. Its radars werent good enough. Its

traffc-handling capacitythat is, the number of missiles it

could deal with at one timewas not adequate.

Also, Nike-Zeus was subject

to something called blackout; that

is, if a nuclear explosion were set

off to destroy an incoming missile,

it also upset the gas in the air,

ionized itelectrons strip off from

the molecules, and for a while the

gas acts like a metal rather than

a gas so that radar waves cannot

go through it and you cannot see

what is behind it. Nike-Zeus was

open to this in two ways. First, if

Zeus (B-Model)

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

12

you fred some rockets and they set off their own nuclear

weapons, you might generate self-blackout. Second, if the

enemy recognized that the defense had this vulnerability, he

could design his offensive system to occasionally dump in

a rocket with a nuclear warhead, explode it, and generate

enough ionization to black out your radars. But, Nike-

Zeus had another interesting weaknessby the time it had

been brought down to a reasonably low altitude so that the

atmosphere would flter incoming devices, no one could be

sure that when it set off its nuclear explosion it would not

damage itself.

Still another problem with the Nike-Zeus was that its

destruction of the incoming nuclear weapons depended on

a phenomenon called neutron heating. When one explodes

a nuclear weapon near another nuclear weapon, a fux of

neutrons is released; these penetrate into the guts of the

second nuclear weapon and heat it enough to melt it.

However, this effect does not work over very great distances;

so the Nike nuclear explosion could be effective against

only a limited number of incoming targets. Although I do

not think that cost factors are the most important part of the

argument against the ABM, this did create an economic case

against it.

The Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations both looked

beyond Zeus for a more

capable ABM system. What

emerged was a layered ABM

system called Nike-X. It

employed many advanced

technologies, including a

new family of electronic

phased array radars that

could detect and track a large

Sprint Zeus/Spartan

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

13

number of objects simultaneously;

a new terminal defense interceptor

called Sprint, which made possible

the use of atmospheric fltering

to discriminate between enemy

warheads and decoys; and it retained

the Zeus missile, subsequently

modifed and renamed Spartan, for

high-altitude targets.

The Kennedy administration announced

reorientation of its ABM efforts in the improved

and more robust Nike-X Project in January

1963. The following month, Secretary of

Defense Robert S. McNamara testifed before

the Senate Armed Services Committee that

the Soviet Union would have the capability

of deploying an antimissile missile system

by 1966. After Secretary McNamara added

that the Nike-X Project should be ready by 1970, Senator Strom

Thurmond (D-S.C.) began an effort to feld the controversial Nike

Zeus ABM system as soon as possible as an interim hedge against

the possibility of a period in which there will be a defensive gap

in U.S. strategic security. On April 11, Senator Thurmond led an

extraordinary effort in Congress to revitalize and

accelerate the Nike Zeus Project. In the frst Senate

closed session held in twenty years, the Senate

assessed the merits of Thurmonds arguments,

but determined that the proposed Nike-X Project

had more promise than revitalizing the Nike

Zeus Project.

Despite Senator Thurmonds failed effort

to revitalize the Nike Zeus ABM, its successful

developments were instrumental in establishing

Thurmond

Special Collections,

Clemson University

Libraries

McNamara

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

14

the foundations for its successor, the Nike-X Project, a more capable

ballistic missile defense system. In particular, Nike Zeus developers

gained vital knowledge of what worked and what failed while

advancing discrimination and characterization studies, radar and

computer technologies, and high-speed, high-heat missile design.

For example, Zeus developers theoretically examined concerns about

the effects of high-altitude

nuclear detonations on radar

signals and subsequently

verifed their fndings in tests

at Johnson Island in the North

Pacifc. Studies showed that

radar signal attenuation from

nuclear explosion effects

could be mitigated by using

higher frequency signals. As

a result, the Zeus acquisition

radar design was modifed to double the planned frequency from 500

to 1,000 megahertz. However, these higher frequency radars were

never produced or tested. Other successful development examples

included the Zeus target intercept computer for guidance of the Zeus

ABM and the Zeus missile booster engine. The computer, designed

with a modular construction of nearly 175,000 components, was

the fastest and most reliable ground computer developed to date in

the nations defense program, and the 450,000 pound-thrust booster

engine was the most powerful single solid propellant motor ever

successfully fred in the United States up to that time.

Following the decision not to deploy Nike Zeus, the Army

continued the test program until December 1964 at White Sands

Missile Range and May 1966 at Kwajalein Missile Range. During

this period Nike Zeus also served briefy as a potential antisatellite

weapon. The Army initially proposed employing a modifed version

of Zeus as an anti-satellite weapon to the Defense Department in

1957, shortly after the Soviets launched Sputnik. The Defense

Zeus Acquisition Radar

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

15

Department adopted the proposal in early 1962, when Secretary

McNamara asked the Army to prepare the Zeus system for possible

use in destroying satellites. The new program became known as

Project MUDFLAP and used modifed Zeus missiles in a variety of

antisatellite tests at White Sands and Kwajalein. From 1963 to 1964,

the Army maintained Zeus in readiness from Kwajalein to intercept

satellites, if required. Testing resumed in 1964 and continued until

the Nike Zeus Projects termination in 1966.

In retrospect, the Nike Zeus Project, the U.S. Armys frst effort

at developing a strategic ballistic missile defense system, was an

ambitious and controversial undertaking. The pioneering Nike Zeus

Project demonstrated the feasibility of intercepting an ICBM, but the

systems technical and operational shortcomings made it impractical

to deploy. Despite these shortcomings, the Nike Zeus Project played

a pivotal role in preparing the way for its successor, the Nike-X

Project, a more capable ballistic missile defense system.

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

16

NIKE ZEUS SYSTEM

The following Nike Zeus system description is from Branches

of the Army, ROTC Manual 145-70, Headquarters, Department of

the Army, October 18, 1963:

The Nike Zeus system is designed to protect the United States

from intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) attack. It uses the

guidance techniques developed and the experience gained from

Nike Ajax and Nike Hercules.

The Zeus system is composed of individual components that can

be assembled in a building-block scheme. The modular design

permits ease of increasing operational capabilities and tailoring of a

Zeus defense complex to meet requirements consistent with the size

and importance of the area to be defended. A Zeus defense complex

might consist of one Zeus defense center (ZDC) and one or more

Zeus fring sites.

Nike Zeus Operation

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

17

A typical target for Zeus would be an ICBM warhead streaking

toward an area at a speed of about ffteen thousand miles per hour.

It may be surrounded by a cloud or decoys, which the ICBM has

ejected en route in an attempt to confuse the defense. Far out in space

the entire cloud is located by the beams of the Zeus acquisition radar

(ZAR) which has the sky under constant surveillance.

The ZAR, located at the ZDC, has a very long detection range and

uses separate transmitting and receiving antennas. The transmitting

antenna is triangular in shape and rotates three hundred sixty degrees

in azimuth. The receiving antenna, which is hemispherical in shape

provides omnidirectional coverage and rotates in synchronism with

the transmitting antenna. Because of this rotation, radar return signals

are focused successfully on each of the three racks of feedhorns

to obtain target information. This information is processed by a

computer to develop the data necessary for threat evaluation and

weapon assignment. Once the computer determines that the object

being tracked is a cloud of decoys, the entire cloud is brought under

surveillance of a discrimination radar (DR) at the battery.

The Zeus fring battery will use three types of radars:

discrimination radars (DR) for determination of the target from

decoys, target tracking radars (TTR) for precision tracking of

targets, and missile tracking radars (MTR) for guiding the Nike

Zeus antimissile missiles to their targets. The DR ferrets the

warhead from the surrounding decoys and pinpoints this incoming

target for the TTR. The hyperaccurate TTR then provides precise

target information to the Target Intercept Computer during the fnal

phase of the engagement. The computer determines the trajectory

of the target, examines it considering the Zeus missile performance

characteristics for an optimum intercept, and launches the antimissile

at the proper instant from an underground launching cell.

N i k e Z e u s : T h e U . S . A r m y s F i r s t A B M

18

After launch, the MTR transmits steering orders to guide the

Zeus missile to the kill point, which may be inside or outside the

earths atmosphere. At this moment the Zeus warhead detonates,

destroying the invader.

Several Zeus missiles can be in the air simultaneously, each on

the way to its own intercept and obeying control orders meant for

it alone. The Zeus missile is a solid-propellant rocket consisting of

three stagesa booster, sustainer, and the jethead stage containing

the warhead and onboard guidance.

The Zeus testing program has resulted in successful intercepts of

both simulated and real ICBM targets.

The current Army Research and Development Program for

ballistic missile defense of the continental United States includes

two major tasks. First, the present Zeus test program will be

continued. This program has been most valuable in providing

information for development in the areas of ballistic missile defense

and penetration aids for offensive missile systems. The second task

will be to emphasize and accelerate the development of a system

presently known as Nike X. Nike X is an advanced antimissile

system made possible by the experience and knowledge gained in

the development of Zeus. For some time now the Army has been

investigating advanced radar antimissile confgurations as part of

the Zeus program. Nike X will employ an advance radar, the Sprint

missile, and a large number of components developed in the Zeus

program. Design and hardware developments have been initiated on

these items.

Nike family of missiles

(L to R): Ajax, Hercules, and Zeus

D

E

P

A

R

T

M

E

N

T O

F

D

E

F

E

N

S

E

M

I

S

S

I

L

E

D

E

F

EN

S

E

A

G

E

N

C

Y

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- History of The Jupiter Missile System PDFDocument190 pagesHistory of The Jupiter Missile System PDFRichard Tongue100% (2)

- Nike AjaxDocument12 pagesNike AjaxIshrat Hussain Turi100% (1)

- Study Into The Business of Sustaining Australia's Strategic Collins Class Submarine CapabilityDocument88 pagesStudy Into The Business of Sustaining Australia's Strategic Collins Class Submarine Capabilitytokalulu8859100% (1)

- History of The Redstone Missile SystemDocument198 pagesHistory of The Redstone Missile SystemVoltaireZeroPas encore d'évaluation

- Agni MissileDocument19 pagesAgni MissileSHIVAJI CHOUDHURYPas encore d'évaluation

- The U.S. Air Force in Space, 1945 To The 21st CenturyDocument204 pagesThe U.S. Air Force in Space, 1945 To The 21st CenturyBob AndrepontPas encore d'évaluation

- S-200VE Vega-E (SA-5B Gammon) Long Range SAM Simulator DocDocument52 pagesS-200VE Vega-E (SA-5B Gammon) Long Range SAM Simulator DocTamas VarhegyiPas encore d'évaluation

- Anti-Ship Missiles of India and Pakistan ComparedDocument6 pagesAnti-Ship Missiles of India and Pakistan Comparedshehbazi2001100% (1)

- Modern Russian Air Force RebuildDocument24 pagesModern Russian Air Force RebuildГригорий ОмельченкоPas encore d'évaluation

- HATF-IX / NASR Pakistan's Tactical Nuclear Weapons: Implications For Indo-Pak DeterrenceDocument50 pagesHATF-IX / NASR Pakistan's Tactical Nuclear Weapons: Implications For Indo-Pak DeterrenceAditi Malhotra100% (1)

- Missile DefenseDocument181 pagesMissile Defensesjha1187Pas encore d'évaluation

- 01 V Zhuravlev EWADE 2011 PDFDocument67 pages01 V Zhuravlev EWADE 2011 PDFMaria SultanaPas encore d'évaluation

- GAPA: Holloman's First Missile Program, 1947-1950Document6 pagesGAPA: Holloman's First Missile Program, 1947-1950TDRSSPas encore d'évaluation

- Cruise Missiles and NATO Missile Defense. Under The Radar?Document61 pagesCruise Missiles and NATO Missile Defense. Under The Radar?IFRIPas encore d'évaluation

- Analysis of G LEO Kinetic Bombardment AnDocument28 pagesAnalysis of G LEO Kinetic Bombardment AnpsuedonymousPas encore d'évaluation

- Wilson-Dunham MissileThreat 20200826 0Document27 pagesWilson-Dunham MissileThreat 20200826 0adnan gondžićPas encore d'évaluation

- Defence Scientific Information & Documentation Centre, DRDO: Published byDocument52 pagesDefence Scientific Information & Documentation Centre, DRDO: Published byPRATHMESH NILEWADPas encore d'évaluation

- Strategic Equipments and Thermonuclear DevicesDocument234 pagesStrategic Equipments and Thermonuclear DevicesDrabrajib HazarikaPas encore d'évaluation

- Air Independent Power SystemsDocument14 pagesAir Independent Power Systemsknowme73Pas encore d'évaluation

- China Nuclear Weapons ReportDocument55 pagesChina Nuclear Weapons ReportNguyen LanPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1. Introduction The Improved Nlke Herculese Missile SystemDocument11 pagesLesson 1. Introduction The Improved Nlke Herculese Missile SystemAmshgautamPas encore d'évaluation

- Nuclear Weapons in EuropeDocument81 pagesNuclear Weapons in Europeuros stefanovicPas encore d'évaluation

- China Naval & SAMs 2010-2011Document29 pagesChina Naval & SAMs 2010-2011DefenceDog100% (1)

- The Cruise Missile Challenge: Designing A Defense Against Asymmetric ThreatsDocument59 pagesThe Cruise Missile Challenge: Designing A Defense Against Asymmetric ThreatsKnut RasmussenPas encore d'évaluation

- Air Defense Artillery - Summer1983Document64 pagesAir Defense Artillery - Summer1983Thomas Baker100% (1)

- Netherlands MCMDocument3 pagesNetherlands MCMaxiswarlordhcvPas encore d'évaluation

- SA-3B GoaDocument39 pagesSA-3B GoaTamas Varhegyi100% (1)

- Optimizing ECM Techniques Against Monopulse RadarsDocument73 pagesOptimizing ECM Techniques Against Monopulse RadarsAre BeePas encore d'évaluation

- ABM Research and Development - Project History. Bell 1975Document478 pagesABM Research and Development - Project History. Bell 1975anonimnez013100% (1)

- Navedtra 14014 AirmanDocument384 pagesNavedtra 14014 AirmanSomeone You Know100% (1)

- Patriot Missile PM PresentationDocument29 pagesPatriot Missile PM PresentationSam Ahmed100% (1)

- Laser Guided MissileDocument10 pagesLaser Guided Missileashutosh1011Pas encore d'évaluation

- Nonacoustic ASW Systems AnalysisDocument55 pagesNonacoustic ASW Systems AnalysisRandyMcDeagPas encore d'évaluation

- PEO SUB NSL Symposium FINAL 24 Oct 13Document22 pagesPEO SUB NSL Symposium FINAL 24 Oct 13samlagronePas encore d'évaluation

- ORPDocument16 pagesORPsamlagronePas encore d'évaluation

- A DarterDocument2 pagesA DarterManuel SolisPas encore d'évaluation

- Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System (SURTASS) and Compact Low Frequency Active (CLFA) SystemDocument2 pagesSurveillance Towed Array Sensor System (SURTASS) and Compact Low Frequency Active (CLFA) Systemjoma11Pas encore d'évaluation

- 1965 Early USAF Man in Space Activities 1955-1960Document48 pages1965 Early USAF Man in Space Activities 1955-1960jsr__526245Pas encore d'évaluation

- Bevan Manpads 2004Document22 pagesBevan Manpads 2004LovacPas encore d'évaluation

- Ohio-Class SubmarineDocument8 pagesOhio-Class Submarinejb2ookwormPas encore d'évaluation

- Sunburns, Yakhonts, Alfas and The Region (Australian Aviation, Sept 2000.)Document14 pagesSunburns, Yakhonts, Alfas and The Region (Australian Aviation, Sept 2000.)Cue Pue100% (1)

- fm3 01Document104 pagesfm3 01Mark CheneyPas encore d'évaluation

- China's Nuclear Warhead Storage and Handling SystemDocument21 pagesChina's Nuclear Warhead Storage and Handling Systemcosmofrog100% (2)

- 2K11M1 KRUG-M1 Simulator DocumentationDocument49 pages2K11M1 KRUG-M1 Simulator DocumentationTamas VarhegyiPas encore d'évaluation

- TM 30-546 1956 Obsolete) Glossary of Soviet Military and Related AbbreviationsDocument184 pagesTM 30-546 1956 Obsolete) Glossary of Soviet Military and Related AbbreviationsBob Andrepont100% (2)

- Cold War Air Defense InfrastructureDocument178 pagesCold War Air Defense InfrastructureFredNad100% (1)

- Nike Ajax HistoryDocument313 pagesNike Ajax HistoryMichel RigaudPas encore d'évaluation

- PLA Guided BombsDocument41 pagesPLA Guided BombsSenho De Maica100% (1)

- helicopter- observation of fire zone;- fireman-parachutists delivery;- evacuation of injured personsDocument21 pageshelicopter- observation of fire zone;- fireman-parachutists delivery;- evacuation of injured personsCésar Rojas Castillo100% (1)

- DefenseDocument209 pagesDefenseSaravanan AtthiappanPas encore d'évaluation

- In0534 Vehicle Recognition (Threat Armor)Document150 pagesIn0534 Vehicle Recognition (Threat Armor)Bob Andrepont100% (1)

- Why The USN and USMC Shouldn't Buy The F-35Document20 pagesWhy The USN and USMC Shouldn't Buy The F-35Black OwlPas encore d'évaluation

- From Auster to Apache: The History of 656 Squadron RAF/ACC 1942–2012D'EverandFrom Auster to Apache: The History of 656 Squadron RAF/ACC 1942–2012Pas encore d'évaluation

- Naval Innovation for the 21st Century: The Office of Naval Research Since the End of the Cold WarD'EverandNaval Innovation for the 21st Century: The Office of Naval Research Since the End of the Cold WarPas encore d'évaluation

- Methods of Radar Cross-section AnalysisD'EverandMethods of Radar Cross-section AnalysisJ.W. Jr. CrispinPas encore d'évaluation

- Cold War Interceptor: The RAF's F.155T/O.R. 329 Fighter ProjectsD'EverandCold War Interceptor: The RAF's F.155T/O.R. 329 Fighter ProjectsÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (2)

- Cannon in Canada, Province by Province, Volume 9: Alberta, Saskatchewan, Yukon, Northwest Territories, and NunavutD'EverandCannon in Canada, Province by Province, Volume 9: Alberta, Saskatchewan, Yukon, Northwest Territories, and NunavutPas encore d'évaluation

- Wings That Stay on: The Role of Fighter Aircraft in WarD'EverandWings That Stay on: The Role of Fighter Aircraft in WarÉvaluation : 3 sur 5 étoiles3/5 (1)

- Threatened by HistoryDocument137 pagesThreatened by HistoryPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Boeing Dyna-Soar Hypersonic Glide VehicleDocument35 pagesBoeing Dyna-Soar Hypersonic Glide VehiclePaul Kent Polter100% (1)

- NOAAdistancesUSports PDFDocument62 pagesNOAAdistancesUSports PDFPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Transferstation BrochureDocument2 pagesTransferstation BrochurePaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Diadochi Wars For DBADocument4 pagesDiadochi Wars For DBAPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Photographs of The Atomic BombingsDocument101 pagesPhotographs of The Atomic BombingsPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- WI Historical Society-Small Boats On A Big LakeDocument144 pagesWI Historical Society-Small Boats On A Big LakePaul Kent Polter100% (2)

- The Naval Engagement of the Texas Republic and Mexico in 1843Document13 pagesThe Naval Engagement of the Texas Republic and Mexico in 1843Paul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- 1947 US Navy WWII 8 Inch 3 Gun Turrets 220p.Document220 pages1947 US Navy WWII 8 Inch 3 Gun Turrets 220p.PlainNormalGuy2Pas encore d'évaluation

- USS Tecumseh Shipwreck Management PlanDocument160 pagesUSS Tecumseh Shipwreck Management PlanPaul Kent Polter0% (1)

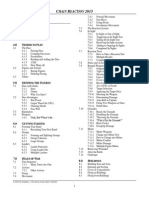

- Chain Reaction-2015 PreviewDocument32 pagesChain Reaction-2015 PreviewPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Babylon 5 Tactics 101Document3 pagesBabylon 5 Tactics 101Paul Kent Polter100% (1)

- We See All-A History of The 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing 1947-1967Document327 pagesWe See All-A History of The 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing 1947-1967Paul Kent Polter100% (5)

- Naval War College Review-Volume 66, Number 4Document156 pagesNaval War College Review-Volume 66, Number 4Paul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Hexographer Manual PDFDocument24 pagesHexographer Manual PDFAntonio Boquerón de Orense100% (1)

- NOAA distances-US PortsDocument62 pagesNOAA distances-US PortsPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Naval War College Review-Volume 66, Number 3Document165 pagesNaval War College Review-Volume 66, Number 3Paul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Naval War College Review-Volume 67, Number 1Document165 pagesNaval War College Review-Volume 67, Number 1Paul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- AFD-100525-029 The 31 Initiatives-A Study in Air Force-Army CooperationDocument177 pagesAFD-100525-029 The 31 Initiatives-A Study in Air Force-Army CooperationPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- CSS Georgia Archival StudyDocument130 pagesCSS Georgia Archival StudyPaul Kent Polter100% (1)

- This Fraudulent Trade-CSA Blockade-Running From HalifaxDocument12 pagesThis Fraudulent Trade-CSA Blockade-Running From HalifaxPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- NASA's Future DiscussedDocument4 pagesNASA's Future DiscussedPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Ironclad Historical Naval ScenariosDocument52 pagesIronclad Historical Naval ScenariosPaul Kent Polter100% (1)

- Boeing Dyna-Soar Hypersonic Glide VehicleDocument35 pagesBoeing Dyna-Soar Hypersonic Glide VehiclePaul Kent Polter100% (1)

- Ironclad Armada RulesDocument10 pagesIronclad Armada RulesPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Lamp Light Part 4Document124 pagesProject Lamp Light Part 4Paul Kent Polter100% (1)

- Ironclad Armada ShipsDocument122 pagesIronclad Armada ShipsPaul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- Nafziger Collection of Orders of Battle-IndexDocument335 pagesNafziger Collection of Orders of Battle-IndexPaul Kent Polter77% (13)

- Project Lamp Light Part 3Document275 pagesProject Lamp Light Part 3Paul Kent PolterPas encore d'évaluation

- United States Navy Fleet Problems and The Development of Carrier Aviation, 1929-1933Document129 pagesUnited States Navy Fleet Problems and The Development of Carrier Aviation, 1929-1933Paul Kent Polter100% (2)

- SOP 001.WI-5.Ramp Arrivals ActivityDocument4 pagesSOP 001.WI-5.Ramp Arrivals ActivityTony RandersonPas encore d'évaluation

- Revolutionary Air-Cooled Heat Exchanger ArchitectureDocument2 pagesRevolutionary Air-Cooled Heat Exchanger Architecturebharath477Pas encore d'évaluation

- 3-DOF Longitudinal Flight Simulation Modeling and Design Using MADocument54 pages3-DOF Longitudinal Flight Simulation Modeling and Design Using MAspbhavna100% (1)

- HAl ProjectDocument100 pagesHAl ProjectNagraj Yadav100% (1)

- Avionics Module 1&2 PDFDocument64 pagesAvionics Module 1&2 PDFNavya nayakPas encore d'évaluation

- Lesson 1212 Arrival Procedures and ChartsDocument32 pagesLesson 1212 Arrival Procedures and ChartsROMEO LIMAPas encore d'évaluation

- Vans Aircraft RV8 Flight ManualDocument28 pagesVans Aircraft RV8 Flight ManualDarren-Edward O'Neill100% (1)

- Katalog CZDocument44 pagesKatalog CZElikaty Servicios AereosPas encore d'évaluation

- ICAO and FAA Standard Phraseology: A Reference Guide For Commercial Air Transport PilotsDocument26 pagesICAO and FAA Standard Phraseology: A Reference Guide For Commercial Air Transport PilotsLucas de AzevedoPas encore d'évaluation

- MIGDocument7 pagesMIGMuhammad RedzuanPas encore d'évaluation

- Aero Modeller 2016-11Document68 pagesAero Modeller 2016-11CB100% (2)

- TCAR 1 - Part 66 AMC - GM - VER 04 - VER FINALDocument208 pagesTCAR 1 - Part 66 AMC - GM - VER 04 - VER FINALjakara tongchimPas encore d'évaluation

- Han1450 ManualDocument94 pagesHan1450 ManualJack CarlPas encore d'évaluation

- Wmo 8 enDocument1 139 pagesWmo 8 enShodiq WinarkoPas encore d'évaluation

- Pilots Handbook of Aeronautical KnowledgeDocument471 pagesPilots Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledgeaske7sp8055100% (3)

- AIR FORCE FLIGHT RULESDocument93 pagesAIR FORCE FLIGHT RULESlpardPas encore d'évaluation

- As350b3e Pmva Pmvs Rn0 Easa Anglais Master TipiDocument359 pagesAs350b3e Pmva Pmvs Rn0 Easa Anglais Master Tipisuperdby100% (2)

- 9868 PANS TrainingDocument174 pages9868 PANS Trainingbenis100% (1)

- Research On Supersonic Combustion and Scramjet Combustors at ONERADocument20 pagesResearch On Supersonic Combustion and Scramjet Combustors at ONERAyoshyroimcPas encore d'évaluation

- Comprehensive Preliminary Sizing and Resizing For A Fixed WingDocument29 pagesComprehensive Preliminary Sizing and Resizing For A Fixed WingNguyen Thanh DatPas encore d'évaluation

- SKRGDocument16 pagesSKRGbrailibPas encore d'évaluation

- Manual Concerning Interception of Civil Aircraft: Doc 9433-AN/926Document62 pagesManual Concerning Interception of Civil Aircraft: Doc 9433-AN/926Максим ВітохаPas encore d'évaluation

- Vohy Iap ChartsDocument8 pagesVohy Iap ChartsAmrinderPas encore d'évaluation

- Marwin Valve Brochure PDFDocument2 pagesMarwin Valve Brochure PDFRoland Bon IntudPas encore d'évaluation

- 15 - 9 International StandardsDocument5 pages15 - 9 International Standardspipedown456Pas encore d'évaluation

- APAME tutorial for aircraft panel methodDocument24 pagesAPAME tutorial for aircraft panel methodmartig87Pas encore d'évaluation

- Rocket Nozzle Design & Flow AnalysisDocument9 pagesRocket Nozzle Design & Flow AnalysisNainan TrivediPas encore d'évaluation

- c-130 Index Service NewDocument16 pagesc-130 Index Service Newangelo marra100% (1)

- Sugar Rocket Reaches New HeightsDocument5 pagesSugar Rocket Reaches New HeightsFarzan ButtPas encore d'évaluation