Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Torche Florencia Social Mobility in Chile

Transféré par

Guillermo RuthlessDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Torche Florencia Social Mobility in Chile

Transféré par

Guillermo RuthlessDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Unequal but Fluid: Social Mobility in Chile in Comparative Perspective Author(s): Florencia Torche Reviewed work(s): Source: American

Sociological Review, Vol. 70, No. 3 (Jun., 2005), pp. 422-450 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4145389 . Accessed: 08/11/2012 16:58

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Sociological Review.

http://www.jstor.org

Unequal But Fluid:Social Mobilityin Chile in Comparative Perspective

FlorenciaTorche

Queens College CUNY Columbia University A majorfinding in comparative mobility research is the high similarity across countries and the lack of association between mobility and other national attributes, with one exception: higher inequality seems to be associated with lower mobility. Evidence for the mobility-inequality link is, however, inconclusive, largely because most mobility studies have been conducted in advanced countries with relatively similar levels of inequality. This article introduces Chile to the comparative project. As the 10th most unequal country in the world, Chile is an adjudicative case. If high inequality results in lower mobility, Chile should be significantly more rigid than its industrialized peers. This hypothesis is disproved by the analysis. Despite vast economic inequality, Chile is as fluid, if not more so, than the much more equal industrialized nations. Furthermore, there is no evidence of a decline in mobility as the result of the increase in inequality during the market-oriented transformation of the country in the 1970s and 1980s. Study of the specific mobilityflows in Chile indicates a significant barrier to long-range downward mobilityfrom the elite (signaling high "elite closure"), but very low barriers across nonelite classes. Thisparticular mobility regime is explained by the pattern, not the level, of Chilean inequality--high concentration in the top income decile, but significantly less inequality across the rest of the class structure. The high Chilean mobility is, however, largely inconsequential, because it takes place among classes that share similar positions in the social hierarchy of resources and rewards. The article concludes by redefining the link between inequality and mobility.

Intergenerational mobility and socioeconomic inequalityare two well-establishedtopics in sociology.Althoughclosely linked,these two aspects of the social distributionof resources and rewards are conceptually distinct (Hout 2004). Whereasinequalitydescribesthe distributionof resourcesat a particular point in time, measureshow individualsmove withmobility

in this distributionover time (Marshall,Swift, and Roberts 1997). As expressed by standard statisticalconcepts,inequalityrefersto the variance of a particulardistribution,and mobility refers to the intertemporal correlation (GottschalkandDanzinger1997).Thus,even if related, there is no necessary association between inequalityand mobility.Furthermore,

Directall correspondence Florencia to Torche, Centerfor the Study of Wealthand Inequality, ColumbiaUniversity,IAB, 420W 118th Street, Rm. 805B, New York, NY 10027 (fmt9@ The thanksPeterBearman, columbia.edu). author Richard Breen, Nicole Marwell, Seymour DonaldTreiman, ASReditors,and the Spilerman, fouranonymous reviewers valuable ASR for advice. The authoralso thanksPaul Luettinger profor

viding the CASMINdataset,and MeirYaishfor the providing Israelimobilitytable.Thisresearch was supportedby the Ford FoundationGrant 1040-1239 to the Centerfor the Studyof Wealth and Inequality, ColumbiaUniversity, by the and Chilean National Center for Science and Technology FONDECYTGrant#1010474 to GuillermoWormald, of Department Sociology Universidad Catolicade Chile.

SOCIOLOGICAL 2005, VOL. 70 (June:422-45o) AMERICAN REVIEW,

SOCIALMOBILITYIN CHILE

423

that assuming thesetwo distributional phenomenacan move in oppositedirections

(Friedman1962). At the theoretical level, approacheslinking mobility and inequalitytend to focus on microlevel mechanisms-the motivations and resources affecting individual decision making-connecting these macrostructuralphenomena.Twoperspectivescan be distinguished. A "resource perspective" indicates that high inequality will result in decreased mobility because the uneven distributionof resources will benefit those most advantagedin the competition for success. In contrast,an "incentive perspective" argues that inequality will raise highermobility. In the end,the questionaboutthe linkbetween intergenerational mobility and socioeconomic ical evidence is thin and inconclusive. Part of the problemis thatmobility has been studiedin

some analystshaveargued growinginequalthat can be offset by a rise in mobility, tacitly ity

in thestakes thecompetition, thereby inducing

is and the inequalityempirical, currently, empir-

all of which share relatively similar levels of inequality.To explore the link between mobility and inequalityat the empiricaland theoretical levels, this article introducesChile to the comparativemobility project. Chile is a middle-income country that has undergone significant political and economic changein the past few decades.In the mid-20th century,the Chilean developmentstrategywas defined by import-substitutiveindustrialization. The economy of Chile was closed to international markets, and the state had a pivotal economic andproductiverole. Mountingsocial problemsassociatedwith unequaldevelopment and urban migration led to two progressive administrationsin the 1960s and early 1970s. These administrationsconductedmajorredistributivereforms,includingthe nationalization of enterprises,an educationalreform, and an reform.This progressivepathwas vioagrarian lentlyhaltedby a militarycoup in 1973. Led by GeneralPinochet, the militarytook power and retainedit until 1990. Once in power,the authoritarian regime conducted a deep and fast market-oriented transformation, consisting of the now standard package of macroeconomic stabilization,privatization of enterprises and social services,

a small ofmostly industrialized countries, pool

and liberalizationof prices and markets.As a result, Chile transformedfrom a closed econointo one of the my with heavy stateintervention if not the most, open and market-based most, economy of the world. After a deep recession in the early 1980s, Chile has experiencedsubstantial sustained and economic growth since the late 1980s, which concurswith the reestablishmentof democratic rule. The period of redemocratizationand growthduringthe 1990s has led to significantly improved living standardsfor the Chilean population.The darkside of this success story is the persistent economic inequality in the country.Inequality, historicallyvery high, grew duringthe militarygovernment,and Chile currently ranks as the 10th most unequal country in the world.The Chileanpatternof inequality can be characterizedby "concentrationat the top": Chile is highly unequal because the wealthiest segment of the society receives a very large portion of the national income, whereas the differences between the poor and middle-income sectors are much less pronounced,lowereven thanin some industrialized nations. Although inequality is by definition associatedwith concentration, Chileancase the is extreme,as comparedwith the industrialized world and even with other Latin American nations. These featuresrenderChile an adjudicative case. If mobility and inequality are related, Chile should show mobility rates significantly differentfrom those of its industrializedpeers. To explore these issues, my analysis includes three components. First, I analyze the Chilean mobility regime in a comparative perspective.Mobility is herein defined as the association between class of origin (father'sclass position) and class of destination (current class position) net of the changes in the class structureover time (structuralmobility). Also known as "relativemobility" or "social fluidity," mobility representsthe level of opennessor degreeof equalityof opportunity in a society. I place Chile in the comparativecontextby fittingthe "coremodel of social mobilfluidity"to the Chileanintergenerational ity table. This model claims to represent the basic similarity in mobility across countries, but it has been tested in only a few, mostly industrialized, countries (see, for example, Eriksonand Goldthorpe1992a, 1992b). By fit-

424

REVIEW AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL

ting the core model to the Chileantable, I determine to what extent Chile departs, if it does, from the assumed internationalhomogeneity in mobility regimes and what the sources of its possible departureare. Even if the core model has become a milestone in comparativeanalysis, it has a numberof undesirableproperties, discussed laterin the Methodssection.Thus,as I a modelingalternative, use a hybridmodel that combines association parametersassuming a hierarchical conceptionof the mobilitystructure, with patternsaccounting for class immobility. of Interpretation these two models provides a detailed description of the Chilean mobility regime, andan evaluationof the main factorshierarchical differences across classes, class inheritance,barriersacross sectorsof the economy-driving Chileanmobility dynamics. Second, I compare the level of mobility in Chile with that of other countries using primary data from France, England, Scotland, Ireland,Sweden, the United States, and Israel. All these countrieshave a much more egalitarian income distribution than Chile. Thus, if the mobility is associatedwith inequality, international comparisonshould show that mobility opportunities in Chile are significantly differentfromthe opportunitiesin these industrialized nations. Third,my analysis moves from an international to a temporalcomparison.To explorethe association between mobility and inequality I further, studyChileanmobilityratesovertime. Using a cohort analysis, I examine whetherthe significant increase in inequality associated with the market transformationof the 1970s and 1980s had any noticeableeffect on Chilean mobility rates. Advancing some of the major results, the findings presentan interestingparadox.On the one hand,the Chileanmobility regime is found to be driven almost exclusively by the hierarchical distancebetweenclasses, which is determined in turn by the level of inequality in the country.This finding is consistentwith the negativerelationship betweenmobilityandinequalOn ity posed by the "resourceperspective." the other hand,the internationalcomparisonindicates thatChile is impressivelyfluid despite its high economic inequality, and the temporal analysis shows no change in Chilean mobility overtime despitethe growinginequalityduring the militaryregime.Therefore,the internation-

al andtemporalcomparisonsseem to contradict the negativerelationshipbetweenmobility and inequality,and to suggest that high inequality may in fact induce mobility. Solving this apparent paradox, I argue, requiresswitchingthe analyticalfocus fromthe level to thepatternof bothmobilityandinequality. When the patternof these two distributive disphenomenais considered,the contradiction appears,andthe mechanismsdrivingthe mobility-inequality association can be examined. The argument organized follows. Section is as 2 presents the empirical and theoretical evidence concerning the association of mobility with inequality. Section 3 describesthe Chilean context. It discusses the most salientcharacteristics of the Chilean socioeconomic structure and presents a brief historical description of the majorchangesin the nationalpoliticaleconomy overthe past few decades. Section4 introduces the dataandanalyticalapproach. Section 5 presentsthe comparativeanalysis of mobility in Chile, including the description of the Chileanmobilityregime,the international comof the fluidity level in Chile, and the parison analysisof changeovertime. Section6 presents a summary of the findings, the conclusions, and the implicationsof the Chileancase for the comparativestudy of inequality. ASSOCIATION BETWEENINEQUALITY AND MOBILITY: AND EMPIRICAL

THEORETICAL EVIDENCE

Although mobility and inequality"go together intuitively"(Hout2004:969), they are different dimensions of the social distribution advanof tage. The former refers to the cross-sectional dimension, which determines the individual The latterrefers position in a social hierarchy. to its intergenerational dimension,specifically to differential access to these positionsas determined by the position of origin (Marshalland Swift 1999:243;Marshallet al 1997:13). At the conceptual level, the differences between these two distributionalphenomena are clear. Inequalitydescribes the distribution of resources at any particularpoint in time. Mobility describes inequality of opportunity, the chancesthatsomeonewitha particular social will attaina morerather thana less advanorigin taged destination regardless of the socioeconomic distancebetweenthese destinations. This

SOCIALMOBILITYIN CHILE

425

are is why "individuals anonymousfor inequalbut not for mobility"(Behrman1999:72).In ity fact,mobilityanalysisassumespathdependence in the reproduction the social structure of across and studies the extent and morgenerations, dependence. phology of such intergenerational The conceptualdifferencemay have important practical implications. As argued by Friedman(1962), and echoed more recentlyby some researchers and policymakers, a given extentof income inequalityunderconditionsof great mobility and change may be less a cause for concernthan the same degree of inequality in a rigid system whereinthe position of "particularfamilies in the income distributiondoes not vary widely over time" (p. 171). The key question is whetherthese two distributionalphenomena are independent. Two theoretical approaches address this question. Both focus on the micro-levelmechanismsthat purportedlylink these macrophenomena:the individual decision-making processes. The "incentive approach"claims that the motivation to pursue mobility is proportionalto the If amountof cross-sectionalinequality. inequality approaches zero, so does the payoff for mobility. Conversely,great inequality increases both the inducementto pursuemobility for those who are initially disadvantagedand the incentiveto resistmobilityforthose who areinitially advantaged. In other words, inequality raisesthe stakesof mobility(Hout2004:970;see also Tahlin2004). The "resource approach" contends that mobility depends criticallyon resourcesrather the thanon incentives.Thehigherthe inequality, greaterthe distance in terms of human, financial, cultural,and social resources across differentsocial origins.In a highlyunequalsociety, the stakes of mobility will be high across the board,but the crucial resources controlled by that individualswill be so unevenly distributed competition certainly will benefit those more 2000:254, Stephens (see advantaged Goldthorpe 1979:54, and Tawney 1965 for a seminal elabThe outcome of high orationof this argument). cross-sectional will inequality be the rigidreproduction of the class structureover time, i.e., low social fluidity. Because resources and incentives work in differentdirections,the effect of inequalityon mobility can be thought of as an additive calculation. If the impact of resources outweighs

that of incentives, we should expect a negative association between inequality and mobility. Conversely,the association should be positive if incentivesaremore relevantthanresourcesin the competition for advantaged positions. In what follows, I argue that consideration of resourcesandincentivesaffectingmobilityat the micro-level should be preceded by a macrolevel understanding of both mobility and should consider inequality.This understanding the patternof these two distributional phenomena, not only their overall level, and should focus on the location and depth of the major cleavages in the social structure.

THE EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

the concerning Empirical evidence association is scarce. mobility-inequality Although high-qualitydataon inequalityexist for a largenumberof countries(e.g., Deininger and Squire 1996), comparabledata on mobility are availableonly for a few, mostly industrialized nations. The most importantsource of comparablemobility data is the Comparative Analysis of Social Mobility in Industrialized Countries (CASMIN)project,whichincludes15 industrialized nations.' The findings of the CASMIN project are highly relevant for the association between mobility and inequality. The CASMIN project concluded that whereas absolute mobility varies across countries and over time because of differences in national relativemobility-the occupationalstructures, association between class of origin and destination net of differences in marginal occupationaldistributions-is extremelyhomogeneous across countriesand over time. These findings were expressed in the "common" and "constant"social fluidity hypotheses, respectively. The basic temporal and internationalsimilarity was systematized into a "core model" of social fluidity (Eriksonand Goldthorpe1987a, 1987b, 1992a; see Featherman, Jones, and Hauser1975 andHauseret al. 1975a, 1975b,for

Theseinclude12 European countries 1 (England, the France, formerFederal Republicof Germany, Northern Poland, Ireland, Scotland, Ireland, Hungary, Sweden,the formerCzechoslovakia, andthe Italy, counand industrial Netherlands) three non-European tries(theUnitedStates, and Australia, Japan).

426

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

the original hypotheses). Common social fluidity is claimed to hold (at least) in industrial societies with a "marketeconomy and nuclear family" (Feathermanet al. 1975:340), and it would be explained by "the substantial uniformity in the economic resources and desirability of occupations" (Grusky and Hauser 1984). The significant international similarity in mobility patterns has been confirmed largely in pairwise or three-countrycomparisons in a few industrialized countries: Erikson, Goldthorpe, and Portocarero(1979), Erikson et al. (1982), and Hauser (1984a, 1984b) for England,France,and Sweden;McRobertsand Selbec (1981) for the United States and Canada; and Kerckhoff et al. (1985) for Englandand the United States.As more industrialized countries were added to the comparative template, it was shown that Sweden and the Netherlands are more fluid (Erikson et al. 1982; Ganzeboom and De Graaf 1984), and that Germany, Japan, and Ireland are more rigid (Hout and Jackson 1986; Ishida 1993; Miller 1986). However,the most strikingfinding was the significant similarityacross countries despite the different historical backgroundsand institutionalarrangements. On the basis of the CASMIN project, a relative consensus has emerged favoring the hypothesis of substantial international similarity in mobility patterns.Similaritydoes not mean complete homogeneity, however. There certainly exist some national deviations, but, it is argued, they can be explained by highly specific, historicallybased institutionalfactors ratherthanby systematic relationshipto other variable characteristics of national societies. There seems to be only one exception to this "unsystematicfluctuation." Comparisonof the CASMIN countries found that a small but significant portion of the internationalvariation in mobility is related to economic inequality, with higher inequality leading to less fluidity (Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992a, chapter 12; also see Tyree, Semyonov, and Hodge 1979 for an earlier analysis). This finding supportsthe resourceapproach linking the two distributive phenomena. Additional evidence consistent with the resources approachwas presentedby Jonsson and Mills (1993), who compared Sweden and England and found higher fluidity in the more

equal Swedish society; by BjorklundandJantti (1997), who compared earnings mobility in the United Statesand Swedenand foundmobility to be higher in Sweden; and by analyses of intergenerationalearnings mobility in several Organizationfor Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, which suggest higher mobility in more equal nations (Solon 2002).2 However,a more recent comparativeanalysis of mobility trends between 1970 and 1990 in 11 industrialized countries does not find evidence of a relationshipbetween inequality and fluidity (Breen and Luijkx 2004a:396). This supportsan earlierindication of no association between the two distributional phenomena (Grusky and Hauser 1984). In sum, evidence about a potential mobility-inequalityassociationbased on cross-country comparisons is inconclusive, not only because of divergent findings, but also because of the small number of countries included and the potentially high collinearity between inequalityand otherexplanatoryfactors. Empiricalanalysis of mobility trendswithin countries has not provided a conclusive answer either.The CASMIN finding of"constantsocial fluidity"over time has been recently tested in the aforementioned comparative analysis of mobility in 11 countries. This analysis, including 10 Europeannations and Israel (Breen 2004), finds growing fluidity in some countries, but null or slight temporal change in others. While Britain, Israel and less conclusively Germany display "constant fluidity"; some indication of growing openness is detected in France, Hungary,Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, and Sweden. However,in France,Hungary,Poland and Sweden all change occurred between the 1970s and 1980s, and stability has prevailed since then (Breen and Luijkx 2004b:54). Changes in Ireland and Italy are quite minor (Layte and Whelan 2004; Pisati and Schizzerotto 2004), and only the Netherlands displays a sustained increase in mobility over the entireperiod considered (Ganzeboom and Luijkx 2004). Mobility has also been foundto

2 Tomyknowledge, is there noempirical evidence

the supporting incentive approach.

SOCIALMOBILITYIN CHILE

427

increase over time in the United States between the early 1970s and the mid 1980s (Hout 1988). However these increases in fluidity are not univocally preceded by a reduction of inequality, thus casting doubts on a potential association between inequality and mobility. A careful analysis of mobility trends in Russia shows a significant decline in mobility associated with an increase in inequality after the market transformationof the early 1990s (Gerber and Hout 2004), which provides additional support for the resource approach.The advantageof the Russian study is that "the market transition in Russia ... altered so many fundamentaleconomic institutions so rapidly that we can confidently ascribe changes in social mobility ... to this source ratherthan to culturalchange or industrialization"(Gerberand Hout 2004:678). It is not clear, however, whether it is growth in inequality,recession, some other change associated with the radical liberalization of the economy, or a combination of these factors that triggered a decline in fluidity in contemporaryRussia. In this context, Chile presents an ideal case for an examinationof the association between inequality and mobility. Given the extreme economic inequality in the country, if the unequaldistributionof resourcesor incentives has an impact on mobility opportunities, the Chilean level of fluidity should be significantly different from that of industrialized nations. Additionally, given the increase in inequality associated with the market reform of the 1970s and 1980s, analysis of mobility before and afterthe reformwould provide supplementaryevidence concerning the potential mobility-inequality relationship. Naturally,a single case study will not supply a definitive answer to these questions. However, by combining an examination of the Chilean mobility regime in the context of historical transformationsin the country with an international comparative analysis, and with an assessment of mobility trends over time, this article provides important insights into the existence of a link between mobility and inequality and the mechanisms driving it.

THE CHILEAN CONTEXT IN COMPARATIVEPERSPECTIVE During the second half of the 20th century, Chile transformedfrom an agrarian,semifeudal society into an urban, service-based one. Between 1950 and 2000, the ruralpopulation declined from almost 40 to 17 percent (Braun et al. 2000; INE 2002). This defines Chile as a mostly urban country, with an 83 percent rate of urbanization,largerthan the 78 percent ratein the United States.In tandemwith urbanization, Chile experienced a reallocation of employment from the agriculturalto the tertiary sector of the economy. The share of agriculture in total employment declined from 38 percentin 1950 to 17 percentin 2000. Whereas the share of manufacturingremainedconstant at about 18 percent, the share of the service sector rose from 42 to 65 percent (Braunet al. 2000; INE 2002). Urbanizationand tertiarizationare processes that virtually all countries experienced during the 20th century.Withinthis seculartrend, the Chilean political economy is marked by specific institutionaldevelopments that shape its stratification structure.From the 1940s to the 1970s, the Chilean economic landscape,as that of its Latin American neighbors, was defined by import-substitutive industrialization (ISI). Emergingas a reactionto the collapse of international trade caused by the Great Depression (Ellworth 1945) and based on the "deterioration of the terms of trade" theory (Prebisch 1950), ISI was based on two types of policies. The first was orientedto closing the Chilean economy to international markets,and the second was oriented to promoting national industrialization.The Chilean state became the leadingproductiveagent, supportingindustry through credit, investments, and technical assistance, and taking a direct productive role through the creation of public enterprises (Stallings 1978). After a sanguine beginning, with industrial production growing at almost 7 percent per year between 1940 and 1950 (Mamalakis 1976; Munoz 1968), ISI startedto fail, economic growth stagnated, and social turmoil resulting from massive urban migration and vast social inequalities increased. In 1964, a progressive administrationtook power and adopted as its mandate the correction of extreme inequality in the country by a

428

REVIEW SOCIOLOGICAL AMERICAN AND PATTERN THE CHILEAN LEVEL OF INEQUALITY

"Revolution in Freedom" (Gazmuri 2000). This progressive government launched redisreform tributivepolicies, includingan agrarian and an educational reform. The redistributive agenda, boosted by a socialist administration that came to power in 1970, was abruptlyhalted by a military coup in 1973. The military took power and retained it until 1990. During these 17 years, the military regime conducted a deep market-oriented transformation. Now turnedinto the "Washingtonconsensus" paradigm (Williamson 1990), this reform included macroeconomic stabilization, deregulation of prices and markets, and the privatization of enterprises and social services. It transformed Chile from a closed economy with heavy state intervention into one of the most open, market-based economies in the world, with the productiveand welfare role of the state reduced to a minimum (Edwardsand Cox-Edwards 1991; Martinezand Diaz 1999; Meller 1996; Velasco 1994). The depth of the market reform coupled with a world recession led in the late 1970s and early 1980s to the deepest economic crisis since the Great Depression. A third of the labor force was unemployed, and poverty afflicted nearly half of Chilean households (Meller 1991). The post-crisis recovery, starting in the late 1980s, was substantialand suswith the and coincided tained, redemocratization of the country. The gross domestic product(GDP) per capitagrew more than 6 percent annually for 15 years, a novel rate for Chile, only comparablein recent times to the "East Asian Miracle" (World Bank 1993). The sharp economic growth has transformed Chile from one of the poorest countries in Latin America (Hofman 2000) into a "middle-income economy" (World Bank 2003a). In the year 2000, the income per capita was approximatelyUS$5,000, much lower than the United States average of US$31,910, but the highest in LatinAmerica (WorldBank 2003a). As a consequence of the sharp economic growth,Chileanshave reachedlevels of consumption unthinkable two decades ago, and the poverty rate fell from 45 to 21 percent between 1985 and 2000 (MIDEPLAN 2000; Raczynski 2000).

The dark side of this "success story" is economic inequality.Structurally rooted in a feudal agrarianstructure,the institutionallegacy of the colonial period, and in the slow expansion of education (Engerman and Sokoloff 1997; World Bank 2003b), inequality has remained persistently high during the 20th century.The Gini coefficient reached.58 in the 1990s, which compares with a much lower Gini of .34 among the industrialized countries, and is large even in the highly unequal Latin American context, with its averageGini of .49 (Deininger and Squire 1996; Marcel and Solimano 1994). As Figure 1 indicates, Chilean inequalityis almost twice that in most industrializedcountries, and 1.5 times that in the United States, the most unequal nation of the industrializedworld. Not only the level, but also the pattern of inequality in Chile significantly departsfrom that of the industrialized world. With the wealthiest Chilean decile receiving 42.3 percent of the total nationalincome (MIDEPLAN 2001), the Chilean pattern of inequality is characterized by high "concentration at the top."Althoughinequalityis by definitionrelated to concentration, the Chilean case is extreme, as compared with the industrialized world, and even with other Latin American countries. A comparison between the income of each decile and the income of the preceding (poorer) decile illustrates the point. The ratio between the wealthiest and the second wealthiest decile is twice as large in Chile as in the United States and England, and one of the largest in Latin America, depicting high elite concentration. In contrast, the ratio between the second poorest and the poorest deciles in Chile is halfthat of the United States and England,indicating that inequality at the bottom of the income distribution is much lower in Chile than in these industrialized nations (Szekely and Hilgert 1999). In fact, as Figure 2 indicates, Chile is the fourth most unequal country in the most unequal region of the world. However, if the wealthiest decile is excluded, Chileaninequalreduced,and Chile becomes ity is dramatically the most equal Latin American country,even more equal than the United States (InterAmerican Development Bank 1999).

SOCIAL IN MOBILITY CHILE 429

0.6 0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2 0.1

Jap

Swe

Ita

Ger

Neth

Fra

Ire

Eng

US

Chile

Countries in Countries Circa2000 Figure 1. IncomeInequality ChileandIndustrialized

Note: Jap = Japan; Swe = Sweden; Ita = Italy; Ger = Germany; Neth = Netherlands; Fra = France; Ire = Republic

of Ireland; = England. Source:World Bank2001. Eng

0.7 0.6

0.5

" 0.4 0.3 S0.2

0 0.

0 Par Bra Ecu Ven Bol US Arg LatinAmericanCountries US and Uru Chile

I TotalGini O Gini ExcludingWealthiestDecile and Decile: Chile, otherLatinAmerican Figure 2. Gini CoefficientforTotalPopulation, ExcludingWealthiest and Countries, Unites Statesin 1998

Note: Par = Paraguay; Bra = Brazil; Ecu = Ecuador; Arg = Argentina; Bol = Bolivia; Ven = Venezuela; Uru =

Bank 1999. Source:Inter-American Uruguay. Development

430

SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW AMERICAN

0.7

.4

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

1957 1961 1965 1969 1973 1977 1981 1985 1992 2000 Years

in Figure 3. Earnings Inequality Greatest Santiago1957-2000 Source:Larranaga 1999andcalculations the author. by

Therefore,Chile is unequallargelybecause the elite concentratesan extremelyhigh proportion of the national income. Across the nonelite classes, the distributionof resources is much more uniform. Inequality is not a new development in Chilean society, but ratherhas deep historical roots. Figure 3 presents the longest available series on inequalityin Chile, depictingearnings distributionsince 1957 in Santiago3and showing persistently high inequality over the last half century.However,thereis significant variationovertime:a shortdeclineof inequality durthe progressive administrations of the ing mid-1960sandearly1970s,an increasesince the military regime took power in 1973, a peak in 1984, and a small decline afterthe democratic transitionto levels still higher than those that preceded the militaryregime.

MARKET LATE INDUSTRIALIZATION, ANDTHECHILEAN REFORM, CLASS STRUCTURE

The "commonsocial fluidity" asserts hypothesis that all internationalvariationin mobility patterns is attributable highly specific, historito cally formed national characteristics. In the Chileancase, these factorsmay be relatedto the marketreformof the 1970s and 1980s and the rapid economic growth since the late 1980s. National mobility studies suggest that countriesexperiencing may rapidindustrialization be characterized weakersectorbarriers mobilto by ity, specifically barriers between the selfemployed and employees and between agricultural and nonagricultural classes (Goldthorpe,Yaish,and Kraus 1997 andYaish 2004 for Israel;Ishida,Goldthorpe, Erikson and 1991 for Japan; Park2004 for Korea; Costaand Ribeiro 2003 for Brazil). In addition,two components of the Chilean markettransformation to may have contributed the weaknessof mobilitybarriers acrosssectors of the economy. The first component is the reformand subsequentcounterreform agrarian undertaken the militaryregime.The second by one is the opening of the economy to international trade and the retrenchmentof the state, which led to a decline in formal employment

3 Santiago, the Chilean capital, comprises about one-third of the country's population.Assessment by Chilean experts suggests that Santiago trends present an unbiasedpictureof trendsat the national level. Although earnings inequality is not as comprehensivea measureas total income inequality,it is an adequate,much more accuratelymeasured,proxy (Galbraith2002).

SOCIALMOBILITYIN CHILE

431

and to the growthand segmentationof the selfemployed sector. The main objective of the Chilean agrarian reform(1962-1973) was to reducethe extreme land concentrationin the country.The reform was very successful. In 1955, the top 7 percent of landownersheld 65 percentof the land, and the bottom 37 percent held only 1 percent. By 1973, the last year of the reform,43 percent of the landhadbeen expropriated (Kay2002; Scott counterreform launched was 1996).An agrarian the militaryregime as a way of returningthe by land to its formerowners. It did not, however, restore the traditionalhacienda order (Gomez and Echenique 1988; Rivera 1988). In fact, the militarygovernmentreturnedonly one-thirdof the plots to theirold owners, sold anotherthird, and adjudicated remainingthirdto the small the proprietorsbenefited by the agrarianreform. Unable to compete with the now cheap food imports, many small proprietorsopted to sell their plots. As a consequence, as much as twoland came up thirdsof the Chileanagricultural for sale, creating an active land market. The of main beneficiaries of the "marketization the countryside"were a new group of export-oriand ented entrepreneurs international investors, who boughtlargetractsof land(Gwynne 1996; Kay 2002). Thus,the reformandcounterreform triggered a massive "change of hands" in the Chileancountryside,likely alteringthe patterns of land inheritance. The secondmajoreffect of the marketreform on the class structure was the reductionof formal employment,caused by the decline of the industrial workingclass andby the shrinkageof the state. Incapableof competingwith the now cheap imports, the working class plummeted from 34 percent of total employment in the early 1970s to 20 percent in 1980, while public employment dropped from 14 to 8.4 percent in the same period (Leon and Martinez 2000; Schkolnick2000; Velasquez 1990). The decline in industrial and public employment led to an increase in self-employment from about 15 percentin 1970 to about28 percentin 1980 (Thomas 1996), followed by a decline through the economic recovery before stabilization at about22 percentof the total employment in 2000 (MIDEPLAN2001). In contrast to industrializedcountries, in which the selfemploymentrateusually is withinthe one-digit range and involves capitalownership,in Chile,

it encompassesmore than one-fifth of the labor force. Furthermore, self-employment had become a survival strategy for a large number of former industrial and public employees, labeled "forced entrepreneurialappropriately ism" (Infanteand Klein 1995; Portes,Castells, and Benton 1989). As a consequence, the Chilean self-employed sector is voluminous and segmented. It includes a small segment of orientedto capital accumulation entrepreneurs and able to hire employees, and a large segment of self-employedworkersmostly engaged in "survival activities" and unable to hire the labor of others. Differences in economic wellbeing between these two groups are massive, with the former group earning, on average, three times more than the latter(MIDEPLAN 2001). To be sure,a largeself-employedsectoris not a result of the market transformation. Selfemploymenthas been historicallyhigh in Latin America because, according to some scholars, the region has experienced "dependent integration" into the world capitalistic system (Hopkins and Wallerstein 1982; Luxembourg 1951). However, the internalheterogeneity of the self-employed sector increased during the marketreform, in a patternthat foretold what happenedin the restof LatinAmericaduringthe 1990s (Klein and Tokman 2000; Portes and Hoffman2003), andwhatmay be currentdevelopments in the industrializedworld (Arumand Miiller2004; Noorderhavenet al. 2003). These characteristics of the Chilean class structure are considered in the comparativeanalysis of Chilean mobility.

DATAAND ANALYTICAL APPROACH

This study uses the 2001 Chilean Mobility Survey (CMS). The CMS is a nationallyrepresentative,multistage, stratifiedsample of male heads of householdages 24 to 69. The sampling strategyincludes the following stages. First,87 primary sampling units (PSUs) (counties) are selected. Then blocks within the PSUs are selected, and finally, households within blocks are chosen. Countiesare stratifiedaccordingto size (fewer than 20,000; 20,000 to 100,000; 100,000 to 200,000; and more than 200,000 inhabitants) and by geographic zone (North, Center,South).All PSUs in the large size stratum are includedin the sampleto increase effi-

432

REVIEW AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL

ciency.The fieldwork,conductedbetweenApril and June 2001, consists of face-to-face interviews in the respondent's householdcarriedout trained personnel. The survey excludes by non-head-of-household males, which represent 17 percent of the male population of the relevant age (MIDEPLAN 2001). Among those excluded, 86.5 percentare the sons of the head of the household, 12.4 percent are anotherrelative of the head,and 1.1 percentare othernonrelated males. Their occupationaldistribution, with controlused for age, is almost identicalto that of the heads of household. The small proportionrepresented this groupandtheirsimby ilar occupationaldistributionsuggest thattheir inclusionwould not significantlyalterthe findings presented in this article. Excluding the households not eligible for the survey, the response rate is 63 percent. Although nonresponse ratesusuallyarenot reportedin Chilean surveys, exchange with Chilean experts indicates thatthe nonresponserateis about20 to 25 percentfor face-to-facehouseholdsurveys.The higher nonresponse rate of the CMS is likely attributableto the difficulty contacting male heads of household.4The total sample size is 3,544. I exclude individuals outside the age range of 25 to 64 years, which is conventionally used in comparativemobility research and cases with unusabledata.After this exclusion, the usable sample size is 3,002.

SCHEMA CLAss

This study uses a class perspectiveto describe the Chileansocial structure. utilizesthe sevenIt version of the classification develcategory oped by the CASMIN project. This classification is widely used in international comparativeresearch,and describes the basic

4 Thenonresponse canyieldbiasif those who rate differ wereunreachable refused participate from or to the thoseincluded the sample. estimate magin To of nitude thisbias,I compared distribution key of the CASENis variables the CASEN2000 survey. with a large conducted theChilean (n by survey = 252,595) and government, has a refusalratelowerthan 10 (available uponrequest) percent.The comparison that underrepresents agrisuggests theCMSslightly howclass.Overall, cultural workers theupper and of ever,thereis no indication majornonresponse bias.

stratification of advanced industrialsocieties based on "employment (Erikson relationships" and Goldthorpe1992a:35-47; Goldthorpeand Heath 1992). The seven classes includedin the nonschemaareI+II(service class), III(routine manual workers), IVab (self-employed workers), V+VI (manual supervisors and skilled manualworkers), VIIa (unskilledmanualworkIVc (farmers),andVIIb (farm workers). ers), Use of the 7-class categorizationinsteadof an alternative detailed 12-class version produced by the CASMIN project (Erikson and Goldthorpe1992b) induces some loss of information about the origin-destination association. A global test of all five aggregations obtainedfrom the ratio of L2tests for the independencemodel in the collapsedand full tables indicatesthatthe seven-class schemamasks29 percentof the association shown by the full set of classes ([L2 full table - L2 collapsed table]/ L2 full table = [1086.44 - 771.91]/1086.44 = .29). This proportion is high compared with thatof the CASMINcountries,and is surpassed only by Sweden, with 31 percent (Hout and Hauser 1992, Table 2). A collapsed sevenfold class schemawas howeverpreferred becauseof the moderatesamplesize of the Chileansurvey, andbecause it grantsinternational comparability of the findings.5 Operationalizationof this class classification is based on detailed informationconcernISCO-88 ingjob title (recodedintothe standard classification [ILO 1990]), industry,occupational status,andsupervisorystatusof workers. Because the CMS is specifically designed to assess class mobility, it includes all the informationnecessaryto producethe CASMINclass schema.The CASMINprojecthas notproduced a standard algorithmto generatethe class classification, but otherresearchershaveproduced such an algorithm,which I use in this analysis (Ganzeboomand Treiman2003). Table 1 presents the basic intergenerational mobility table to be used in this analysis,includingthe counts and marginalpercentagedistributionfor origin and destinationclasses.

5 Analyses 12werereplicated usingthedetailed in class table,and no difference substantive findingswas found.

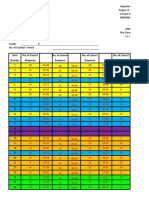

SOCIAL MOBILITY CHILE 433 IN Table 1. Seven-Class Intergenerational MobilityTablefor ChileanMen Classof Destination I-II I-II. ServiceClass III. RoutineNonmanual IVab.Self-employed IVc. Farmers V-VI.SkilledManual VIIa. SemiskilledandUnskilledManual VIIb.Farm Workers N % counts. Note: Cell entriesrepresent 229 61 123 42 91 49 28 623 21% III 49 15 37 16 33 43 16 209 7% IVab IVc V-VI VIIa VIIb N 2 2 81 37 430 30 34 0 24 1 27 162 28 102 173 90 20 573 54 24 68 58 54 316 13 155 135 116 36 579 13 111 123 44 115 498 17 89 101 115 444 78 665 127 576 560 242 3,002 22% 4% 19% 19% 8% % 14% 5% 19% 11% 19% 17% 15%

METHODS

I fit two alternative modelsto the Chileanmobility table.Thefirstis the "coremodelof socialflubasicinternational idity' whichclaimsto capture similarityin mobility.Althoughthe core model for has become a benchmark mobilityresearch, is and currently the only model that providesa comparativeframeworkfor mobility analysis, to analystshave drawnattention a numberof its limitations.The model has been criticized for hierarchical inadequately mobility representing for being tailoredto a few industrialized effects, for countries, the ad hoc natureof some effectsit includes (specifically the affinity effects), and for lacking a criterionto determinehow much divergence is necessary for it to be rejected (Ganzeboom,Luijkx, and Treiman1989; Hout and Hauser 1992; Sorensen 1992; Yamaguchi 1987).I thereforealso test an alternative "hybrid model"thatcombinesthe row-column(II)associationmodel (Goodman1979) with parameters for The accounting classimmobility. international and temporalcomparisonof Chilean mobility uses the uniform-difference patterns (UNIDIFF) also known as the multiplicativelayer model, effect model (Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992a; Xie 1992). Model comparisonand selection is based on the Bayesian InformationCriterion (BIC) statistic(Raftery1995).

basic internationalcommonality in social fluIn idity using a topologicalformulation. contrast from to standard models constructed topological a single allocation of cells (Hauser 1978), the core model uses eight matrices, each of which is designed to capture a particulareffect that enhances or reduces mobility between specific classes (Eriksonand Goldthorpe1987a, 1992a, chapter4). In this way, the model permits the sources of commonality across nations to be identified clearly, and likewise the departures from it. The effects areof fourtypes: hierarchy, inheritance,sector, and affinity.6

HIERARCHY effects reflect EFFECTS. Hierarchy the impact of status distances between classes on fluidity between them. To estimate these effects, the mobility table is divided into three strata,reflecting differences in resources and rewardsacross classes. The strataare the following: upperstratum(class I+II), middle stratum (classes III,IVab,IVc, andV-VI),andlower stratum(classes VIIa andVIIb). Because there are three strata,two hierarchyeffects (HI1 and HI2) can be identified, each representingthe crossing of one additionalhierarchicalbarrier. The associationbetween each pair of classes is expressedas an inverse functionof the number of hierarchicalstratacrossed. INHERITANCE effects are EFFECTS. Inheritance

OF ANALYSIS CHILEAN MOBILITY IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

MODEL SOCIAL OF THECORE FLUIDITY

designed to capture the propensity for class

I startby fitting the core model to the Chilean mobility table. The core model representsthe

Design matricesin Eriksonand Goldthorpe (1992a:124-129).

434

SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW AMERICAN

immobility.They include three matrices: IN1 acrossall classesalike;IN2 identifiesimmobility identifies the higher immobilityof the service class (I+II),the self-employed group(IVab),and farmers(IVc); and IN3 accountsfor the highest immobilityof farmers(IVc). to SECTOR EFFECTS. effectsareintended Sector identify the difficulty of moving between the sectors of the agriculturaland nonagricultural economy(SE1). EFFECTS. AFFINITY Affinity effects are intended to capturespecific discontinuities(negative between affinities) affinities)or linkages(positive classes, which eitherreinforceor offset the overall effects of hierarchy sector.Therearetwo and affinityeffects.The first,AF1, identifiesthe difficultyof movingbetweenthe serviceclass (I+II) andthe class of farmworkers (VIIb),whichadds to their hierarchicaldistance. In contrast,AF2 identifies instances in which mobility is more and thanaccounted by hierarchy secfor frequent toreffects,andincludesaffinitieswithinthenonmanual sector(I+IIandIII)andwithinthemanual sector (V+VI and VIIa):a symmetricalaffinity basedon capitalpossession(IVabandIVc, andI link andIVab)andan asymmetrical betweenagriculturalclasses of origin(IVc andVIIb)andthe unskilledmanualclass of destination (VIIa).7

THE MOBILTY PATIERN CHILE: IN ORDIVERGENCE? CONVERGENCE Table2 presentsthe fit of severalmodelsapplied to the Chilean data, and Table 3 displays the parameterestimates for each of these models. Model 1 in Table2 indicatesthat the fit of the originalcoremodel to the Chileantableis unsatisfactory understandardstatisticalcriteria,but it explains a significant 77.5 percentof associTo ationunderindependence. assess the strength of the differentfactorsdrivingmobility opportunities,I comparethe Chileancoefficientswith those obtained for the CASMIN countries. Coefficients from the original core model fitted to the Chileantable arereportedin row 1 of Table3; CASMIN coefficients are reportedin row 2; and differences in coefficients' magnitude and the statistical significance of the differences are reportedin row 3.8 All Chilean coefficients are significant and have the same sign as for the CASMIN countries. Comparison the magnitudeof the coefof ficients, however,shows significantdepartures from the core for five effects, which reveal interesting differences between Chile and the coefficients CASMIN countries.The hierarchy indicate that whereas the short-rangehierarchical barriersare somewhat weaker in Chile 8CASMIN were from coefficients obtained fitting and tableof France thecoremodelto thecombined

England, standardizingboth tables to have 10,000 cases, as recommendedby Eriksonand Goldthorpe (1992a: 121). The coefficients obtainedare virtually identical to those presented by Erikson and Goldthorpe(1992a, Table4.4).

derivation account theempirical of 7Fora detailed

of the model, see Erikson and Goldthorpe(1987a,

1987b,and1992a,chapter 4).

Table 2. Fit statistics,selectedmodelsto the ChileanMobilityTable L2 BIC df p Association Explained

CoreModel 77.5% 137.5 28.5 28 .000 1. CoreModel,Original 86.0% 108.1 -0.8 28 .000 2. CoreModel,EHE 90.6% 3. Chileanversionof CoreModel([Model2] + ChileanParameters) 72.4 -32.6 27 .000 .000 AssociationModels 90.5% 73.4 -16.1 23 .000 Model 4. Heterogeneous Quasi-RC(II) 89.6% 80.3 -28.7 28 .000 Model 5. Homogeneous Quasi-RC(II) 79.8% 6. Quasi-Linear Linear Association(SES rowandcolumnranking)a 156.3 27.9 33 .000 by hierarchical Note: EHE= empirical effects;SES = eocioeconomicstatus. a Linear-by-linear in association modelusing socioeconomicstatusscoresas presented Appendix FigureAl to classes. rankoriginanddestination

Estimates the ChileanMobilityTable Table3. ModelParameter for Effect 1.Coremodeloriginala HI1 HI2 IN1 IN2 IN3 SE1

.68** .41*** -.38*** -.65*** .39*** -.12* (.10) (.24) (.08) (.07) (. 11) (.05) .84*** 1.01*** .43*** -1.06*** 2. CoremodelCASMINb -.22*** -.45*** (.04) (.11) (.03) (.05) (.04) (.02) -.68*** .20 t 3. Difference, .45*** Insig. Insig. CASMIN--Chilec-.10 t (.11) (.08) (.12) (.06) .31* -.42*** .37*** -.74*** 4. CoremodelEHEd -.03 .61" (.13) (.24) (.07) (.07) (.09) (.07) .48* -.20* -.09 t 5. Chileanversionof coree .34*** -.47*** (.23) (.07) (.08) (.10) (.06) EHE= empirical errorsin parentheses. hierarchical with standard effect estimates Datashownaremodelparameter Note: a Model 1 fromTable2. b Original CoreModelfittedto the EnglishandFrench mobilitytables.See text for details. C Difference parameter in betweenoriginalcoremodelfittedto the Chileantable(row 1) andto the CASMINt magnitude d Model2 fromTable2. e Model3 fromTable2. t P <.1; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed).

436

REVIEW SOCIOLOGICAL AMERICAN

mobility is more (HI1), long-rangehierarchical difficult in this country (HI2). This suggests substantialinequalitybetween the extremes of the class hierarchycombined with smaller difAs ferentiationin the middle of the distribution. to the inheritanceeffects, the service class, the self-employed group, and the farmers(classes I+II, IVab, and IVc, respectively) have a significantly lower propensity to immobility in Chile than in the CASMIN countries,suggesting that class positions usually associated with independent work are less able to reproduce theirclass statusintergenerationally depictthan ed by the core. Most impressive, the barrier between the agriculturaland nonagricultural sectors of the economy (SE1) is much weaker in Chile, as is the affinity effect linking nonmanual classes, manualclasses, and the classes that own capital among themselves (AF2). all Interestingly, the significantdifferencesin coefficients,withthe singleexceptionof the barrier to long-range hierarchicalmobility, suggest thatChile is more fluidthanthe core model depicts. Higher fluidity seems to be drivenby the weakness of horizontalbarriersseparating the agricultural, manual,and self-employedsectors of the economy. This is consistent with findings of weaker sector effects in countries that have experienced rapid industrialization, such as Korea (Park 2004), Brazil (CostaRibeiro 2003), Israel (Yaish2004; Goldthorpe et al. 1997), and Japan(Ishida et al. 1991). Additionally,in the Chilean case, the weakness of sector barriersmay have been intensiof fied by the deep markettransformation the 1970s and 1980s. On the one hand,the "change of hands"in the agriculturalsector inducedby the agrarianreform and counterreformlikely increased fluidity between the agricultural and urbanclasses. On the otherhand,the role of selfemployment, as an ephemeral refuge against (industrial and public sector) unemployment may have reduced barriersbetween the selfemployedgroupandthe rest of the social structure.Addedto the largerdifficultyof long-range hierarchical mobility, these features suggest weak sector cleavages in the Chileanfluidity pattern and high salience of the hierarchical dimension of mobility. For the countriesin which the fit of the core model is not adequate,Eriksonand Goldthorpe (1992a:145) suggest adding parameters that account for country-specific deviations from

to the model. I thereforeintroduceadjustments reflect salientcharacteristics the Chileanfluof idity pattern,producinga "Chileanversion"of the core model. effects.Fitting First,I modify the hierarchical of the core model suggests that hierarchical of barriersare a crucialdeterminant mobilityin Chile. This conclusion is, however, obscured by the fact that the hierarchical stratadistinguished by the core model are not empirically the obtained,and may not accuratelyrepresent Chilean rankingof classes in terms of socioeconomic status (SES). To model hierarchical I effects in Chile adequately, rankclasses using the unweightedaverageof their schooling and earninglevels as a proxyfor SES. I thencollapse the seven classes into three hierarchicalstrata using cluster analysis.These three empirically are obtainedstrata the following:Upperstratum class: I+II), middle stratum(routine (service nonmanual and self-employed group: III and IVab),and lower stratum(manualand agriculturalclasses:V-VI,VIIa,IVc, andVIIb).Details of on the ranking classes,clusterprocedures, and the comparisonof the CASMIN and empirical Chilean class ranking can be found in the of Appendix. Comparison the CASMINandthe class rankingsuggests higherdifferempirical entiation at the top than at the bottom of the social structurein the Chilean case. Model 2 in Table 2 uses the empirically obtained hierarchical strata (EHE). The in improvement fit is massive (the differencein BIC is 29.3, withoutusing any degreesof freedom). The model now accounts for 86 percent of the association underindependence. in The largeimprovement fit when empirical hierarchical strata are used challenges the assumptionof an internationally homogeneous hierarchical class ranking. At the empirical level, there is no proof that the hierarchical rankingof classes assumed by the core model fits all CASMIN countries.9Moreover,some difevidencepointsto significantcross-country

9Erikson Goldthorpe(1992a, 2.2)presand Table enttheaverage of ranking classesbasedonstandard but status measures, theydo notshowtheempirical If of ranking classesfor eachcountry. the occupational of across countries, composition classesvaries international in there differences maybe significant thehierarchical of ranking classes.

SOCIAL MOBILITY CHILE 437 IN

ferences in the ranking of classes (Hout and Hauser 1992; Sorensen 1992). At the theoretical level, the creatorsof the core model highlightthe relevanceof highlyspecific, historically formed national attributesto explain internationalvariationin mobility.These nationalparticularities may very well result in different hierarchicalpositions of classes across countries.10Furthermore, even if the homogeneous ranking of classes imposed by the CASMIN researchers applied to most CASMIN countries, significant departuresmay be found in the late industrialized countriescurrently being addedto the comparative mobility project.The Chileanfindings suggest thatinsteadof imposing international homogeneityto the hierarchical dimensionof mobility,the rankingof classes shouldbe treatedas nationallyspecific parameters to be estimated,as mobility researchers routinely treat row and column marginals of the mobility table. The issue is important because the hierarchicaldimension is the most relevant dimension of mobility (Hout and Hauser1992;Wong 1992),andinadequate modeling can bias assessment of not only hierarchical effects of mobility but also othereffects. Two other changes were introduced to account for Chilean-specific deviations from the core model. First, the IN2 effect was to rearranged exclude the self-employed class and to includethe class of farmworkers (IVab) (VIIb). This rearrangementaccounts for the fact that the Chilean self-employed class appearedless likely than depicted by the core model to reproduce its class position across and level of Chilean generations; the inheritance farm workers is higher than in the CASMIN countries.These changes are expressed in the IN2-C. Chilean-specificinheritanceparameter Second, an affinity parameter (AF1-C) was added to capture the difficulty of long-range downwardelite mobility. This negative asymmetrical affinity links flows from the service

class to the agriculturalclasses, and from the routine nonmanual class to the class of farm workers.Note that the AF l-C adds to the hierarchical distance between the two extremes of the class structure,and to the negative affinity captured AF 1 to depictthe extremedifficulty by of long-range downward mobility from the Chilean elite. The fit of this 'Chilean version' of the core model is reportedin Table2, model in 3. The improvement BIC frommodel 2 is substantial. Furthermore,even if the model falls short in terms of standardstatisticalcriteria,it accounts for a large 91% of the association under independence, thereby supporting the claim that it adequatelyrepresentsthe Chilean The estimatesforthe mobilitypattern. parameter Chileanversion of the core are reportedin row 5, Table3. Because of the coremodel'sundesirable properties, I also use an alternative approach to examine Chilean mobility patterns. This approach uses the now standard association row-column (II) (RC[II]) model (Goodman 1979; see also Hout 1983, and Wong 1992). In this model, both origin and destinationclasses are scaled so that the association can be interactionby a expressed as a linear-by-linear single parameter.The multiplicative form of the model can be expressed as follows: Fij= TTi0 TjD exp(4 gi vj), where i indexes class of origin,j indexes class of destination,Fijis the expected frequencyin the (ij) cell, 7 is the grand mean, 7ri pertains to the class of originmarginal effect, 7jD pertains to the class of destinationmarginaleffect, 4 is a global association parameter,gi is the scale value for the ithclass of origin,andvj is the scale score for the jth class of destination,subject to the following normalizationconstraints: Lti = of lvj = 0 (normalization the location)andIgi2 = Ivj2 = 1 (normalizationof the scale). The class scale scores reflect a latent continuousvariablemade manifestby the class categories. Empirically obtained from the data, these "distance" scores produce an optimal ranking of classes for the purpose of mobility analysis. The RC(II) model is appropriatefor modeling the association of any two ordinal variables, but mobility tables are distinctive because of the correspondence betweenclass of andclass of destination (GerberandHout origin 2004:691).

10 For instance,duringthe socialist period in the of Hungary, status theproletariat havebeen may from of nonindistinguishable thestatus theroutine manual class(Szelenyi1998:62). Scotland, In given to earlyindustrialization, hierarchical the barrier between skilled unskilled the and classes that working characterizes CASMIN other countries notexist may and (Erikson Goldthorpe 1992a:163).

438

SOCIOLOGICAL AMERICAN REVIEW

I introducetwo adjustmentsto account for this correspondence,transformingthe formulation into a "hybridmodel."First,topological will account for the large counts in parameters some diagonal cells reflecting immobility (inheritance)effects. These parametersdistinlevels: "highinheritance" guish two inheritance for the service class (I+II), farmers(IVc), and for farmworkers(VIIb), and "low inheritance" all otherclasses, with the exception of the routine nonmanualworkers. Model 4 in Table2 reportsthe fit statisticfor this quasi-RC(II) model. The BIC statistic rejects it and prefers the more parsimonious Chilean version of the core model. Therefore, I introducea second adjustmentto account for the correspondence betweenrows and columns in mobilitytables.Originanddestinationscores are constrainedto be the same, assuming that the scaling of classes has not significantly changed over time. Model 5 in Table2 reports fit statisticsfor this homogeneousquasi-RC(II) model. On the basis of the BIC statistic,the fit of the model is as good as that of the Chilean version of the core model (Wong [1994] shows thatBIC differencesof less than5 points should be consideredindeterminate). Thus,understandardstatisticalcriteria,the Chileancore model and the homogeneous quasi-RC(II)model are Giventhatthe Chileanversion indistinguishable. of the core model was tailoredto fit the Chilean and table,the fit of model 5 is impressive, it indicates thata unidimensional scale can adequately capturemobility distances between classes. The logical next question is what this scale represents, and specifically whether it represents the hierarchical rankingof classes in terms of SES. If a close correspondence is found between the mobility distances among classes and their distances in terms of SES, this finding would suggest that the intragenerational of distribution resourcesandrewardsexpressed in the SES rankingof classes drivesthe process ofintergenerational mobility.In otherwords,this finding would supportthe resourceapproach's claim that differences in resources associated with diverse class positions determinemobility opportunitiesacross generations. To examine this possibility, I compare the class scores obtained from the homogeneous quasi-RC(II) model with the empirically obtained SES rankingof classes based on education and earnings(Appendix).Figure4 pres-

ents the comparisonbetween the standardized values of both sets of scores. The correspondence is striking. The mobility distances between classes closely reproduce their distances in termsof SES. This close isomorphism suggests that, at least in Chile, the intragenerational inequality in the distributionof social resources and rewards across classes largely drivesthe intergenerational mobilityprocess.To test the isomorphism further, I use the SES class scores as row and columnrankings estito mate a quasi-linear-by-linear associationmodel (model 6, Table 2). The fit of model 6 is significantly worse thanthatof model 5, almostas pooras thatof the originalcore model.Thisindicates that althoughthe inter- and intragenerational dimensionsof inequalityarevery similar in Chile, they have a somewhatdifferentstructure. In summary, centralcharacteristic the the of Chileanmobilityregimeis the predominance of long-rangehierarchicalbarriersand the weakness of sectorcleavagesseparating classesin the middle and at the lower end of the hierarchical structure.Findingsfrom the "Chileanversion" of the core model and the quasi-RC(II)hybrid models are consistent, depictinga social structure characterized by significant barriers betweenthe top echelon andthe restof the class structure. The good fit of the homogeneous quasi-RC(II)model providespreliminarysupport for the resourceapproachlinkinginequality and mobility.Mobility dynamicsseem to be driven largely by the hierarchical distances betweenclasses, andoverall,Chile seems not to be less fluid than the CASMIN countries.

OF COMPARISON THEORIGINAL CHILEAN AND

OF VERSIONS THE MODEL CORS AlthoughChileanmobilitydynamicsseemto be driven by inequality across classes in a very unequal society, the fitting of the core model that providesno indication Chileis significantly less fluid than depicted by the core model. As a preliminary analysisof the Chileanlevel of fluI comparethe predictedpropensitiesfor idity, mobility andimmobilitybetweenspecific pairs of classes in Chile with those in the CASMIN countries. Propensities are obtained from the originalandChileanversionsof the coremodel, respectively (models 2 and 5 of Table3).

IN SOCIAL MOBILITY CHILE 439

2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 CO-0.5

-1.0

-1.5 Service (I+II) Farm Routine SelfSkilled Unskilled Farmers Non- Employed Manual Manual Workers (IVc) manual (VIIb) (IVab) (V+VI) (VIIa) (III) Social Classes

- - - SES Scores (1) Mobility Scores (2)

fromthe Homogeneous Model andfromSocioeconomicStatus Quasi-RC(II) Figure 4. Class ScoresObtained (SES) Ranking socioeconomicstatusscoresbasedon schoolingandearnings; = Class stanNote: (1) = Class standardized (2) model(see text for details). dardized scoresbasedon the Homogeneous Quasi-RC(II)

I beginwith the immobilityof those at the top of the class structure,namely the service class (I+II).The service class' propensityfor immobility in the originalcore model is capturedby two parameters,IN1 and IN2. This propensity is more thanthreetimes what it would be in the absence of these effects (e.43+.84= 3.56). In for Chile,thepropensity immobilityof class I+II is capturedby the same two parameters,and it is lower than what the core model expresses: 2.86 times largerthanit wouldbe in the absence Whataboutthe immoof these effects (e.34+.71). of the two agricultural classes? In the bility CASMIN countries,immobilityof the IVc and 7.85 and 1.54 times VIIbclasses is, respectively, whatit would be in the absence of these parameters (e.43+.84+1.01-.22 e.43,respectively). In and the comparablevalues are4.22 and 2.86 Chile, and (e.34+.71+.48-.09 e.43+.71, respectively), indithe relativelylow inheritanceassociated cating with land ownership in the Latin American nation. Thus, if attention is focused on the immobility in the upper and lower ends of the the social hierarchy, comparisondoes not indicate less fluidity in the highly unequalChilean society.

What about the mobility rates between the ranktwo most distantclasses in the hierarchical ing, namely, the service class (I+II) and farm workers (VIIb)? In the case of the CASMIN countries, the mobility chances between these classes are capturedby four parameters(HI1, H12, SE1, and AF1), and is .077 times smaller than it would be in the absence of these effects (e-.22 -.45-1.06-.83). In Chile, the distance from class I to class VIIb is expressedby these same four parametersin addition to the asymmetrical disaffinity AF1-C. This yields mobility chances .056 times what would be obtained in the absenceof these effects (e-.09-.47-.20-.63-.1.49). Thus, the barrier to long-range downward mobility from the elite is more significant in Chile thanin the CASMIN countries.The same occurswith long-range downward mobilityfrom class III. If we measure the reciprocal flow (i.e., upwardmobility from class VIIb to class I+II), we obtain the same value for the CASMIN countries,because all parametersare symmetrical in the originalcore model. ForChile, however,this calculationremovesthe asymmetrical barrierto elite downwardmobility,which rais-

44o

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

es the chances of mobility to .25 of what it would be in the absence of these effects

(e-.09 -.47-.20-.63). Surprisingly for a society with

such a high level of inequality,the barrierto mobilityis significantlyless long-rangeupward than in the CASMIN countries. What about the relative chances of moving between classes that are closer in terms of status?The Chileanversionof the core model suggests thatthe patternshouldbe as fluid in Chile, if not more so, because of the weak sector effects. For example, in CASMIN countries, the propensity to move from the farmer class (IVc) to the unskilledmanualclass (VIIa)is .44 times what it would be in the absence of these In contrast,in Chile there effects (e--22-1.06+.45). is higherfluidity,with mobility 1.28 times what neutral mobility would be (e-.20+.45). Again, there is no indication of more rigidity in the Chilean fluidity pattern. Finally,I comparethe mobilityflows between the voluminous skilled and unskilled working classes. Whereas in Chile there is no effect modifying the fluidity between classes V-VI and VIIa, in the CASMIN countries, they are separatedby a hierarchicaleffect, but connected by an affinityeffect.This marginally increases fluidity to 1.08 of what it would be in the absence of this effect (e-.26+.34),indicating no significant internationaldifferences. These case-by-casecomparisonssuggestthat although hierarchical effects, especially those associated with long-range downwardmobilityfrom the elite, are stronger in Chile, sector barriers are weaker yielding a pattern that is as fluid, if not more so, than that in advanced industrialnations. A THE LEVEL FLUIDrTY CHiLE: OF IN MULTICOUNTRY COMPARISON To explore furtherthe level of fluidity in Chile in an international context, I compare the strength of the origin-destination association between Chile and seven industrializedcountries: England, France, Sweden, Ireland, Scotland, the United States, and Israel. The rationalefor includingthese countriesis as follows. Englandand Franceare the centralcountries from which the core model was derived (EriksonandGoldthorpe1987a, 1987b, 1992a); Sweden and the United States are among the most fluid countries in the CASMIN pool;

Scotland and Ireland are found to be among the most rigid nations within the CASMINset (Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992a, chapter 11); and Israel is the most fluid society in which empirical studies have been conducted,significantly more fluid than any of the CASMIN et countries(Goldthorpe al. 1997;Yaish2000).11 In orderto assess cross-nationalvariationin social fluidity,I fit a set of models forthe threeway table of class of origin, class of destination and country (Table 4). The model of conditional independence,assuming no association between origins and destinationsacross countries given differentnationalmargins(Table4, column 1), is presented as a baseline against which othermodelsmaybe assessed.As expected,the fit is verypoor,indicatingsignificantorigin-destination association in the countries analyzed. The second model tested is thatof"common fluidity,"which postulates that the strengthof the origin-destinationassociation is the same across countries.12As column 2 of Table 4 shows, the model significantly improves the fit, when compared with conditional independence (L2= 987.2 df= 252 BIC = -1767.8). Although the model does not fit the datawell under standardstatistical criteria, it accounts for a large 96 percentof the associationunder independence. I then turn to the question of international To variation. test the hypothesisthatthe strength of the origin-destination association varies across countries, I use a model independently developed by Xie (1992) and Erikson and Goldthorpe(1992a), and known as the multiplicative layer effect, or uniform difference (UNIDIFF).The multiplicativeformulationof the model is the following:

I Dataon England, the France, Sweden, United and wereobtained the from Ireland, Scotland States, CASMIN Data wereobtained from dataset. on Israel the 1991 IsraeliSocialMobilitySurvey. Samples to arereduced menages25 to 64 yearsin theCASand MIN countries, to Jewishmen ages 25 to 64 yearsin Israel. 12 Note thatthisis notthe coremodelof fluidity estimated theprevious in but section, a fullinteractionmodel,whichusesone parameter eachcell for of the table, but constrains parameters be the to acrosscountries. homogeneous

SOCIAL IN MOBILITY CHILE 441 Table4. Fit Statisticsfor MobilityModelsin EightCountries Model L2 df BIC AssociationExplained Israel Chile USA Sweden 4 England 4 France 4 Ireland Scotland 1. Conditional Indendence 16971.7 288.0 13823.0 0.0% 2. Common Social Fluidity 987.2 252.0 -1767.8 94.2% 3. UNIDIFF 639.7 245.0 -2038.8 96.2% .25 .26 .30 .31 .39 .41 .42 .43

deviationfromoverallorigin-destination association(see text for details). Note: 4 = country-specific

70 i

D TkC 7ikOC TjkDC exp(ij4k),

Fijk

7=

where i indexes class of origin,j indexes class of destination, k indexes country, Fijk is the expected frequency in the (i,j,k) cell, the 7 are norparameters subjectto the ANOVA-type malization constraint that they multiply to 1 dimensions, n represents along all appropriate the grandmean, pertainsto the class of oriri0 gin marginaleffect, jD pertainsto the class of destinationmarginaleffect, Tkc pertainsto the describes the oricountry marginaleffect, 4ij association over all countries, gin-destination and the 4ks describethe country-specificdeviation fromthe overallassociation.The extentof association in country k is now the product of two components:the origin-destination association commonto all countriesandthe national deviationparameter 4k.13 As indicatedby column 3 of Table4, the fit of the model is significantly improved when the strength of association is allowed to vary across countries.The 4ks indicatecountry-specific departures from the overall level of association.14 The larger the country-specific

deviation Pkparameter,the stronger the origin-destinationassociationin countryk, i.e., the less fluid the country is. Comparison of the parametersyields a striking conclusion: Chile is morefluidthanany of theadvancedEuropean countries, andhas a level of fluidityin between the highly fluid United States and Israeli societies. Findinghigh fluidityin a developingcountry is not completelynovel. In fact, Park(2004) demonstrated that Korea is more fluid than France, England, and even Sweden. However, economic inequality in Korea is comparable with that in advanced industrial nations (Deininger and Squire 1996). Whatcontradicts a resource approach-based expectation is to find high fluidity in a country with one of the highest levels of inequalityin the world.15

THELEVEL SOCIAL OF OPENNESS CHILE: IN TEMPORAL COMPARISON

I Alternatively, could have used the log-additive 13 model (Yamaguchi layer 1987).Theproblemwith this model is its requirement thatthe origin and destination categories be correctly ordered (in terms of mobility distances),which producesa differentresult

To explore further the association between mobility and inequality,I examine the change in mobilityratesovertime in Chile.Specifically, I test whetherfluidity has changedacross three periods:the redistributive period (1964-1973), the markettransformation period (1974-1988), and the growth and democratization period

foreachcombination origin destination of and orderand ing (Goodman Hout1998;Xie 1992). 14 Xie's(1992)formulation, scaleof the Following

the 4k parameters normalized thatXj4k2equals 1. is so

15Note thatI cannot say anythingaboutthe sources of fluidity in a particular country by using this method. Instead of a summarytest such as the one used here,this wouldrequirea local test in which spe-

cific setsof cells aremodeled(Wong1990).

442

AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

(1989-2000). Given the significant increase in inequalityduringthe marketreform(as Figure 3 indicates,the period-average Gini index grew from.49 to .55), an associationbetweeninequality and fluidity shouldexpress itself as a significantchangein mobilityratesduringthatperiod. The advantageof a trend analysis is that by focusing on a single country, it controls for unobservedfactorsproducing international variation. However,because the data come from a single, cross-sectionalstudy,I dividethe sample into threesuccessive birthcohortsandinterpret intercohortchange as period effects. The first cohort (born between 1937 and 1943) reached occupationalmaturity-defined in this analysis as 30 years old-between 1967 and 1973, during the redistributive period.The second cohort between 1944 and 1958) reached occu(born pational maturity during the market transformation period (1974-1988). The third cohort (born between 1959 and 1970) reached occupationalmaturityduringthe periodof sustained economic growth and democratization (1989-2000). As is well known, a limitationof cohort analysis is the inability to distinguish betweenlife cycle (age),period,andcohortinterof The pretations change(Ryder1965).16 poteneffectsof life cycle differences tiallyconfounding are minimized by including only individuals who have reachedoccupationalmaturity, under the assumptionthatthere is little careermobility afterthatpoint (Goldthorpe1980;Heathand Payne 1999).17However, the analysis cannot distinguishbetweencohortandperiodinterpretations of change.To assess changes over time, I use the UNIDIFFmodel introduced the prein vious section. Panel A in Table 5 presents the parameter estimates for the model of conditional independence (model 1), the "constantsocial fluidity" model (model 2), and the UNIDIFFmodel model (model 3). The conditionalindependence

16 It also is important note thatas a cohort to

growsolder,it suffersattrition some members. by here Thus,thegroups analyzed arenottruecohorts, but their currentsurvivors(Goldthorpe1980). Studies industrialized in countries define usually 17 as occupational maturity the age of 35 years.For thisstudy, years agewaschosen theChilean 30 of for case becauseof the earlier entryto workthatcharacterizes nations. developing