Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Journal of Affective Disorders: Marianne Wyder, Patrick Ward, Diego de Leo

Transféré par

Florina AndreiDescription originale:

Titre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Affective Disorders: Marianne Wyder, Patrick Ward, Diego de Leo

Transféré par

Florina AndreiDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Journal of Affective Disorders 116 (2009) 208213

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Affective Disorders

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s ev i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / j a d

Research report

Separation as a suicide risk factor

Marianne Wyder a, Patrick Ward b, Diego De Leo a,

a Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Suicide Prevention, Grifth University, Mt. Gravatt Campus, Queensland 4111, Australia b School of Integrative Biology, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland 4067, Australia

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Background: Marital separation (as distinct from divorce) is rarely researched in the suicidological literature. Studies usually report on the statuses of separated and divorced as a combined category, possibly because demographic registries are not able to identify separation reliably. However, in most countries divorce only happens once the process of separation has settled which, in most cases, occurs a long time after the initial break-up. Aim: It has been hypothesised that separation might carry a far greater risk of suicide than divorce. The present study investigates the impact of separation on suicide risk by taking into account the effects of age and gender. Methods: The incidence of suicide associated with marital status, age and gender was determined by comparing the Queensland Suicide Register (a large dataset of all suicides in Queensland from 1994 to 2004) with the QLD population through two different census datasets: the Registered Marital Status and the Social Marital Status. These two registries permit the isolation of the variable separated with great reliability. Results: During the examined period, 6062 persons died by suicide in QLD (an average of 551 cases per year), with males outnumbering females by four to one. For both males and females separation created a risk of suicide at least 4 times higher than any other marital status. The risk was particularly high for males aged 15 to 24 (RR 91.62). Conclusions: This study highlights a great variation in the incidence of suicide by marital status, age and gender, which suggests that these variables should not be studied in isolation. Furthermore, particularly in younger males, separation appears to be strongly associated with the risk of suicide. 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Article history: Received 8 July 2008 Recieved in revised form 11 November 2008 Accepted 12 November 2008 Available online 6 January 2009 Keywords: Suicide Marital status Separation Divorce Risk of suicide

1. Introduction Even though there has been some suggestions that marital separation may be associated with an increased risk of suicide (Cantor and Slator, 1995; Hillman et al., 2000; Kposowa, 2000), separated people (i.e. still married but not living together anymore) have been largely ignored in suicide research. In fact, in most investigations, those who were separated were classied either as married or single indivi-

Corresponding author. Tel.: +61 7 3735 3377; fax: +61 7 3735 3450. E-mail address: d.deleo@grifth.edu.au (D. De Leo). 0165-0327/$ see front matter 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.007

duals or grouped together with divorced subjects. This is of concern as marital breakdown is associated with increased risk of psychological distress (Maughan and Taylor, 2001). The few studies that have included separation as a distinct category suggested that the risk could be especially high for separated males (Cantor and Slator, 1995; Kposowa, 2000). Theoretically, the effect of marriage and relationship breakdown is expected to differ by gender and age (Mastekaasa, 2006). Status integration theory suggests that infrequent or uncommon combinations of social statuses and roles make social relationships unstable (Gibbs, 2000). Little is known about the way age, gender and marital status affect suicide rates (Kposowa, 2000).

M. Wyder et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 116 (2009) 208213

209

Furthermore, there is currently considerable debate whether the relationship between marital separation and adverse outcome on health reect causal inuences (the distress associated with marital separation) or selection effects (psychologically healthy people are more likely to marry and to remain married) (Cheung, 1998; Goldman, 1993; Hemstrong, 1996; Hope et al., 1999; Joung, 1997; Smith et al., 1988). Similarly, some have suggested that the association between separation and/or divorce and suicide would be better explained by the effect of a psychiatric illness (Cheung et al., 2006; Kessler et al., 1999), with the latter either interfering with separation, suicide or both. The present study aimed to investigate the prevalence of suicide among separated people by taking into account the effect of age and gender. Psychiatric illness was also controlled for. 2. Methods This study adopted the following categories of marital status: married or in a de facto relationship, separated, divorced, single/never married, and widowed. Marriage is dened as two people living together as husband and wife as per the Australian Marriage Act (1961). A de facto marriage is dened as the relationships between a man and a woman who are not legally married but live together as husband and wife. In Australia, separation is dened as the period between the marital break-up and the divorce, and occurs as soon as one spouse permanently leaves the conjugal home (Family Law Act 1975; Marriage Act 1961). Divorce is granted only after a couple has been separated on a continuing basis for at least 12 months. While separation from a de facto relationship carries similar obligations as separation from a formal marriage it does not require a formal divorce. In the current investigation, separations from these two types of marriages are treated as equivalent. 2.1. Data sources Records of suicide were obtained from the Queensland Suicide Register (QRS), a database maintained by the Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention (AISRAP), which records all cases of suicide in Queensland (QLD). Information in this database comes from coroners and police reports, as well as from psychological autopsy forms designed by AISRAP and completed by police ofcers with proxies of the deceased. The psychological autopsy interview includes demographics, life events, psychiatric history of the deceased and other information deemed relevant by the investigating ofcer (see De Leo and Klieve, 2007; De Leo et al., 2006 for a more detailed description). The period analysed for this study spanned from 1994 to 2004. During this period, the marital status of suicide victims was not reported in 19% of the cases. It should be noticed that in this databank, operating uninterruptedly since 1990, the collection of psychiatric data relied on information collected during coroner's investigation and through interviews (Form 1) by police with proxies of the deceased and eventually GPs. Currently, in the QSR the incidence of psychiatric illness is of 39.6% (QSR latest reading: 22.5.2008), a percentage remarkably lower than those usually

reported in the literature (for example: Lnnqvist, 2000). The low incidence of psychiatric illness in the QSR can be explained by the fact that the data collection relies on police and coronial information only. The incidence of psychiatric illness is commonly lower when purely based upon coroner's information (Snowdon et al., submitted for publication). In fact, different types of quality-control studies performed on the QSR database have brought to different results in terms of frequency of psychiatric diagnoses (De Leo and Krysinska, 2008). In one of these studies, a trained psychologist performed the same interview (Form 1) with proxies of the deceased at six-month distance from the event. The percentage of detectable psychiatric conditions increased to 55% (representative sample of 100 cases). When the SCID (Spitzer et al., 1996) was added to the interview, the percentage increased to 67.5% (consecutive sample of 260 cases; De Leo et al., in preparation). The latter study did not included suicides aged 35 and under. It is also important to note that, while minor mental disorders may not be included within the dataset, the prevalence of major depression, bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders in the QSR appears to be congruent with studies involving mental health interviewers or structured diagnostic instruments (De Leo and Klieve, 2007). The 1996 and 2001 Queensland population censuses (latest available at the time of manuscript preparation) were used as a proxy for the state population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2001a,b). The census information includes two separate classications for marital status, namely the Registered Marital Status and the Social Marital Status. The Registered Marital Status refers to legal status categories such as married, never married, widowed, divorced and separated. Consequently, those who live in a de facto relationship are mostly classied as never married (and, less frequently, as widowed or divorced). On the other hand, the Social Marital Status considers current living arrangements and categorises in married in a registered marriage, married in a de facto marriage and not married. By combining these two classications, the number of people recently separated (from marriage or de facto relationships) could be counted. Due to misclassications associated with the marital status categories across the two registries, a certain number of persons fell into more than one category. In fact, in the 1996 census 12,091 persons (.5% of the total sample) were classied twice. No person was classied twice in the year 2001. 3. Statistical analysis The contributions of age, gender and marital status to suicide risk were assessed using likelihood ratio tests. Maximum likelihood in a linear regression modelling of suicide risk was performed by considering each subject as a binomial trial in the sense of being in the QSR or not. Regression models for the effects of age, gender and marital status on the probability of being in the suicide register were tted using the glm module of the R statistical package (R Development Core Team, 2006). Errors were assumed to follow a binomial distribution, and the log link function was used (rather than the logit default) in order to directly estimate relative risk. Subjects with incomplete information were excluded from the analysis. Suicide risks

210

M. Wyder et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 116 (2009) 208213 Table 3 Relative risks (RR) and condence intervals (CI) for suicide by gender, marital status and age. Age 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ Status Married Married Married Married Divorced Divorced Divorced Divorced Separated Separated Separated Separated Single Single Single Single Widowed Widowed Widowed Widowed RR and CI for males (95%) 7.57 (5.3210.79) 3.97 (2.935.37) 3.35 (2.464.54) 4.12 (35.66) 20.69 a 7.97 (5.6911.16) 6.85 (4.939.51) 6.31 (4.119.68) 91.62 (59.65140.7) 33.53 (24.6345.64) 17.6 (12.724.39) 11.61 (7.3218.4) 4.55 (3.366.17) 7.83 (5.7910.60) 4.04 (2.835.67) 2.38 (1.583.6) 10.73 (4.5823.74) 6.25 (3.7310.49) 8.16 (5.7711.55) RR and CI for females (95%) 1.39 (.882.19) 1.16 (.841.60) .89 (.631.26) 1 (Reference category) 2.46 (1.673.62) 1.91 (1.292.85) 1.22 (.582.59) 4.27 (1.5411.85) 3.65 (2.485.38) 3.63 (2.345.63) 1.58 (.495.08) 1.13 (.801.59) 2.29 (1.623.24) 1.17 (.701.97) .25 (.09.71) 2.41 (.966.06) 1.45 (.842.51) .85 (.561.29)

Table 1 Chi-Square test for main effects, two- and three-way interactions between age, gender and marital status (QSR compared to QLD Census population). Factor Age Gender Age and gender Marital status Age and marital status Gender and status Age, gender and status df 3 1 3 4 12 4 12 Chi-square 145.4 1972.9 8.6 1276.2 207.6 64.1 20.034 P-value b.0001 b.0001 b.05 b.0001 b.0001 b.0001 ns

are expressed relative to risk of suicide by married females over the age of 65. The estimates of relative risk were based on the average of the 1996 and 2001 census counts. Even though the Queensland population did not remain static during this period, the relative risk of suicide followed similar patterns across categories of marital status, age and gender regardless of whether the 1996 or the 2001 data were used. Logistic regression was also used to assess the distribution of unknown marital status across categories of age and gender. Logistic regression was also performed to assess the effects of age, gender and marital status on the occurrence of psychiatric illness as reported within subjects in the QSR. A similar logistic regression was performed on one of the Quality Control Studies (representative sample of 100 cases). 4. Results Between 1994 and 2004, 6062 persons died by suicide in QLD (an average of 551 per year) and males outnumbered females by four to one (see Table 1 for detail). The main effects

a The condence intervals for young divorced males have not been included as the numbers in this category were too small and the estimate of the variance was considered to be unreliable.

Table 2 Distribution of marital status of males and females in QSR and QLD. Age Marital status Males in Males in QLD Females Females in QLD QSR in QSR (n) (n) Average Average 19962001 a (n) 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+ 15 to 24 25 to 44 45 to 64 65+

a

19962001 a (n) 31 217 122 45 0 59 53 8 4 59 36 3 120 113 21 4 0 5 18 43 41,688 349,043 255,355 84,084 659 44,852 51,713 12,256 1749 30,144 18,487 3546 198,680 92,011 33,464 29,372 278 3881 23,150 94,374

Married Married Married Married Divorced Divorced Divorced Divorced Separated Separated Separated Separated Single Single Single Single Widowed Widowed Widowed Widowed

96 653 486 250 4 137 170 39 37 386 179 30 548 593 94 45 0 7 21 109

23,606 307,037 271,109 113,050 356 31,991 46,215 11,514 718 21,136 18,834 4802 224,511 140,920 43,448 35,300 132 1213 6258 24,852

and two-way interactions between age, gender and marital status were all signicant (Table 2). The three-way interaction was not signicant, indicating that the trends seen across age and marital status may be considered parallel between males and females. Overall, males had a higher suicide risk (RR = 4.12) than females. While the trends observed across all categories of age and marital status for males broadly mirrored those of females it is important to note that the condence intervals for divorced and separated females were overlapping suggesting that there were no signicant differences between these two categories. For females, while there were no signicant differences between the marital status of separated, there was some suggestion that both decreased with age. In contrast, among single women suicide risk was elevated only for those aged 2544 years (RR = 2.29). Being single and over 65 years of age appeared to be a protective factor (RR = .25) (Table 2). Younger separated males were at the highest risk (RR = 91.62); this risk progressively decreased with age (RR = 11.6 for those over 65). Compared to the other marital statuses, divorced men also had a substantial higher risk of suicide, which also decreased with age. However, for divorcees the risk was overall less than half of separated men. The risk for

Table 4 Chi-Square test for two- and three-way interactions of psychiatric illness on age, gender, marital status (based on QSR dataset). df Age Gender Marital status Age and marital status Age and gender Gender and status Age, gender and status 3 1 4 11 3 4 10 2 47.3 112.5 10 21.3 2.4 2.3 16 P b .0001 b .0001 b .05 b .05 ns ns ns

The ABS census data does not include QSR data.

M. Wyder et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 116 (2009) 208213 Table 5 Chi-square values from log-linear model for main and two-way interaction effect of psychiatric illness on age, gender and marital status. P-value 1524 2544 45 to 64 65+ Male Female Divorced Never married Separated Widowed Married 15 to 24 Divorced 25 to 44 Divorced 45 to 64 Divorced 15 to 24 Never married 25 to 44 Never married 45 to 64 Never married 15 to 24 Separated 25 to 44 Separated 45 to 64 Separated 15 to 24 Widowed 25 to 44 Widowed 45 to 64 Widowed The asterisk stands for Reference Category. b .0001 ns ns Reference category b .0001 RC ns ns ns ns RC ns ns ns b .0001 b .003 b .02 ns ns ns b .04 ns

211

single men was also high among those aged 25 to 44 (RR = 7.83) and low for those over 65 (RR = 2.38) (Table 2). Those of unknown marital status (19% of suicides) were analysed separately. Their characteristics did not signicantly differ from the total sample in terms of age, gender and presence of psychiatric conditions. In the QSR data, a psychiatric condition was mostly present among males who had never married and were between the ages of 15 and 44. However, no association with either separation or divorce and psychiatric illness was found (Tables 3, 4, and 5). The analysis of the Quality Control Study yielded similar results. The psychiatric illness was mainly present among those who had never married (regardless of age or gender) (chi-square 12.6, df = 5 and P b.05). 5. Discussion This study highlighted that the prevalence of separated males and females was much higher than any other marital status, even when compared to those who were divorced. Furthermore, the results indicate that the effects of age, marital status and gender should not be studied in isolation, since a more intricate picture emerges when a full crossclassication is considered. For example, while separation or divorce represented a higher risk for all age groups, the risk was particularly high in the younger age groups. Marriage had the lowest relative risk for those aged 65 and over, but did not appear to benet those aged 15 and 24. Conversely, the relative risks for single people in the younger age groups were lower but peaked in the 25 to 44 year old age group. Durkheim (1897/1951) suggested that marriage provided protection against suicidal behaviours, as people would be more integrated in a supportive social network. When these bonds are broken by separation and divorce, the risk for suicide would increase (Durkheim, 1897/1951). This theory

still receives support today (Giddens, 2001; Hassan, 1996, 1998; Jacob et al., 2003; Stack, 2000). Gibbs and Martin (1964) hypothesised that those marital statuses that occur infrequently in society lead to higher role conict, which in turn increases the risk of suicidal behaviours. For example, in countries where divorce is rare, the suicide rates for divorced people are higher (Gibbs and Martin, 1964; Gibbs, 2000). In most western societies being married and divorced under the age of 25 is rare (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2001a,b) and people within this age group and marital categories are more likely to experience higher levels of stress. For example, the nancial and emotional stressors in young married couples may be greater than in older ones (Yip and Thornburn, 2004). Conversely, the stress of being single between the age of 25 and 44, a period where most people marry and start a family, may increase the risk of suicide because people may feel that they have failed to achieve their own goals. Similarly, it has been suggested that variables like antisocial behaviour, alcohol or substance abuse and conduct disorders are positively related to early partnership formation (Forthofer et al., 1996; Fu and Goldman, 1996; Maughan and Taylor, 2001) and that children from disrupted homes are more likely to marry and have children at an early age (McLanahan and Bumpass, 1988; Kiernan and Cherlin, 1999). Similar ideas were found in the life course literature where there is a distinction between on-time and off time events. This literature suggests that those experiencing off-time events (in this case separating at a young age) would have less coping skills to deal with the psychological distress experienced (Mastekaasa, 2006). It is possible that pre-existing issues such as psychiatric illness, anti-social behaviour or poor coping skills may have contributed to the relationship breakdown and suicide. Conversely the relationship breakdown may have caused intense feelings of distress which inuenced the suicide. From the current study it is difcult to make denite conclusions about the impact of separation or pre-existing vulnerabilities as other risk factors such as education, income and presence or absence of children were not controlled for. These variables may inuence both marital status and suicide. Equally, it is possible that the relationship breakdown actually caused the distress as for many people the loss of a relationship is an inherently stressful life event, which could produce feelings of low self esteem and loneliness. These feelings may lead to depression, hopelessness and suicidal ideation, which in turn may trigger/facilitate suicide (Dieserud et al., 2001; Kposowa, 2000). In the current study there was some suggestion that the association between separation and suicide risk was largely independent from the presence of a psychiatric illness. This nding parallels that of Duberstein et al. (2004), who showed that the association between family and social/community indicators of poor social integration and suicide is largely independent from psychiatric disorders. Whether or not it is the pre-existing condition or the separation that is causing the distress it is important to consider that separation and divorce both constitute a high risk for suicide, with separation (especially in males aged 1524) appearing to be a particularly challenging condition. Marital breakdown is associated with an increased risk of psychological distress (Maughan and Taylor, 2001) and that the impact of this stress is the highest in the rst year of the separation. General studies into separation have suggested that men and women

212

M. Wyder et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 116 (2009) 208213

who had experienced a relationship breakdown and were alone at the time of the interview experienced the highest levels of mental health difculties (Mastekaasa, 2006). The period of separation is a particular stressful time for many people and, for some could signicantly contribute to the development of suicidal behaviours. The elevated risk of suicide for divorced females reported by Cantor and Slator (1995) in QLD between 1990 and 1993 disappeared between 1994 and 2004. This change may mirror a trend in western countries for the ratio of divorced to married suicides to narrow (Charlton, 1995; Hassan, 1995; Heikkinen et al., 1995; Kposowa, 2003; Lorant et al., 2005; Smith et al., 1988; Stack, 1990; Trovato, 1986; Yip and Thornburn, 2004). Furthermore, while the trends observed across all categories of age and marital status broadly mirrored those of females, suicide risk for males was much higher. This higher risk may reect the way males socialise, as they more often rely solely on their partners for emotional and social support, whereas females often have a wide network of family and friends who provide this support. Consequently, the greater protection from suicide in women may be attributed to their higher degree of attachment to signicant others (Cantor and Slator, 1995; Trovato, 1991). Traditional notions of masculinity may partly explain men's vulnerability to suicide, as males are more likely to avoid demonstrations of emotion or vulnerability that could be construed as weakness (Courtenay, 2000; Davis et al., 1999); to inhibit emotional expressiveness and choose aggression and risk-taking as responses to stressful events (Grossman and Wood, 1993; Moller-Leimkuhler, 2002a,b); to use avoidant coping strategies (Halstead et al., 1993); and to limit help-seeking behaviour (Barker and Adelman, 1994; Murphy, 1998; Oliver et al., 1999). All these attitudes have been independently linked to suicidal behaviours (Jacob et al., 2003; Murphy, 1998). In the current study, those who were single and over 65 presented the lowest relative risk of suicide, both in men and women. This nding appears to contradict previous evidence that marriage is the most consistently protective factor against suicide (Ben Park and Lester, 2006; Gunnell et al., 2003; Leenaars and Lester, 1995; Lester, 1994; Lorant et al., 2005; Yip and Thornburn, 2004). However, one previous study has reported similar results, with older suicides being signicantly more likely to be married or widowed (Carney et al., 1994). It is possible that over the years, older single people have developed strong social networks and coping strategies and are therefore better equipped to deal with life's stressors on their own. 6. Limitations

signicantly inuenced the results. Lastly, this study only investigated the impact of marital separation on suicide risk but did not control for other variables such as education, income, the presence or absence of children which previous studies have shown can also signicantly impact upon separation/divorce as well as suicide risk. The study did control for psychiatric illness, however information regarding psychiatric illness at the time of the suicide is based on police interviews with proxies at the time of the death. As was noted, for a variety of reasons, the incidence of psychiatric illness may be underreported in the QSR, especially when illicit drug use and minor psychiatric conditions (e.g., anxiety disorders and personality disorders) were involved. However the fact that the prevalence of major depression, bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders is similar to those reported elsewhere in the literature (De Leo and Klieve, 2007) and, that the logistic regressions performed on the QSR and Quality Control Study yielded similar results, appears to corroborate the nding that suicide risk in separation is independent from the presence of a psychiatric illness. 7. Conclusions The data from this study strongly suggests that separation, in particular for younger males, is an important risk factor for suicide. However, we cannot be certain that this is due to the separation itself or some characteristics of these males that are both related to the early life transitions (like marriage and separation) and suicide. Considering the current raise in divorce rates (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2001a,b; Carmichael et al., 1997), the increasing number of de facto marriages, and the large proportion of suicides that are associated to relationship breakdowns, a better understanding of how the transition from marriage to separation and/or divorce may inuence the development of suicidal behaviours could have a powerful inuence on reducing suicide rates.

Role of funding source Nothing declared. Conict of Interest No conict declared.

Acknowledgement Queensland Health provides continuing support to the Queensland Suicide Register. References

A number of limitations should be noted. Firstly, the information regarding marital status was missing for 19% of the suicides. While there was no suggestion that any particular age and/or marital status category had been subject to different degrees of underreporting, it is possible that this may have affected the results. Secondly, the category of married/de facto for the QLD population was based on a combination of two different marital classication systems. While more than 99.7% of the population was only classied once in the merging of the two systems, it is possible that further misclassications were introduced within different marital statuses. However, it is unlikely that these may have

Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2001a. Registered Marital Status by Age by Sex Time Series Statistics (1991, 1996, 2001 Census Years) Queensland. Canberra. Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2001b. Social Marital Status by Age by Sex Time Series Statistics (1991, 1996, 2001 Census Years) Queensland. Canberra. Barker, L., Adelman, H., 1994. Mental health and help-seeking among ethnic minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 17, 251263. Ben Park, B., Lester, D., 2006. Social integration and suicide in South Korea. Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide 27, 4850. Cantor, C., Slator, P., 1995. Marital breakdown, parenthood and suicide. Journal of Family Studies 1, 91102. Carmichael, G., Webster, A., Mcdonald, P., 1997. Divorce Australian style: a demographic analysis. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage 26, 3.

M. Wyder et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 116 (2009) 208213 Carney, S., Rich, C., Burke, P., Fowler, R., 1994. Suicide over 60: the San Diego study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 42, 174180. Charlton, J., 1995. Trends and patterns in suicide in England and Wales. International Journal of Epidemiology 24, S4552 Suppl. Cheung, Y., 1998. Can marital selection explain the differences in health between married and divorced people? Findings from a longitudinal study of a British birth cohort. Journal of Public Health 112, 113117. Cheung, Y., Law, C., Chan, B., Liu, K., Yip, P., 2006. Suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts in a population-based study of Chinese people: risk attributable to hopelessness, depression, and social factors. Journal of Affective Disorders 90, 1931999. Courtenay, W., 2000. Constructions of masculinity and their inuence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Social Science and Medicine 50, 13851401. Davis, M., Matthews, K., Twamley, E., 1999. Is life more difcult on Mars or Venus? A meta-analytic review of sex differences in major and minor life events. Annals of Behavioural Medicine 21, 8397. De Leo, D., Klieve, H., 2007. Communication of suicide intent by schizophrenic subjects: data from the Queensland Suicide Register. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 1, 16, doi:10.1186/1752-4458-1-6. De Leo, D., Krysinska, K., 2008. Suicidal behaviour by train collision in Queensland, 19902004. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 42 (9), 772779. De Leo, D., Klieve, H., Milner, A., 2006. Suicide in Queensland, 20022004: mortality rates and related data. Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention, Brisbane. Dieserud, G., Roysamb, E., Ekeberg, O., Kraft, P., 2001. Towards an integrative model of suicide attempt: a cognitive psychological approach. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 31, 153168. Duberstein, P., Conwell, Y., Conner, K., Erberly, S., Caine, E., 2004. Suicide at 50 years of age and older: perceived physical illness, family discord and nancial strain. Psychological Medicine 37 (1), 137146. Durkheim, E., 1897/1951. Suicide, a study in sociology. Routledge, Glencoe. Family Law Act 1975. Attorney General's Department: Canberra. Forthofer, M.S., Kessler, R.C., Story, A.L., Gotlib, I.H., 1996. The effects of psychiatric disorders on the probability and timing of rst marriage. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 37 (2), 121132. Fu, H.S., Goldman, N., 1996. Incorporating health into models of marriage choice: demographic and sociological perspectives. Journal of Marriage and the Family 58, 740758. Gibbs, J.P., 2000. Status integration and suicide: occupational, marital, or both? Social Forces 78, 363384. Gibbs, J., Martin, P., 1964. Status Integration and Suicide. University of Oregon Press, Oregon. Giddens, A., 2001. Sociology. Polity Press, Cambridge. Goldman, N., 1993. Marriage selection and mortality patterns: inferences and fallacies. Demography 30, 198208. Grossman, M., Wood, W., 1993. Sex differences in intensity of emotional experience: a social role interpretation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65, 10101022. Gunnell, D., Middleton, N., Whitley, E., Dorling, D., Frankel, S., 2003. Why are suicide rates rising in young men but falling in the elderly? A time-series analysis of trends in England and Wales 19501998. Social Science and Medicine 57, 595611. Halstead, M., Johnson, S., Cunningham, W., 1993. Measuring coping in adolescents: an application of the Ways of Coping Checklist. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 22, 337344. Hassan, R., 1995. Suicide Explained. Melbourne University Press, Melbourne. Hassan, R., 1996. Social factors in suicide in Australia. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminology. Australian Institute of Criminology. Hassan, R., 1998. One hundred years of Emile Durkheim's Suicide: a study in sociology. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 32, 168171. Heikkinen, M., Isometsa, E., Marttunen, M., Aro, H., Lonnqvist, J., 1995. Social factors in suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry 167, 747753. Hemstrong, O., 1996. Is marriage dissolution linked to differences in mortality risk for men and women? Journal of Marriage and the Family 58, 366378. Hillman, S., Silburn, S., Zubrick, S., Nguyen, H., 2000. Suicides in Western Australia 1986 to 1997. Ministerial Council for Suicide Prevention, Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, Centre for Child Health Research, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Perth. Hope, S., Rodgers, B., Power, C., 1999. Marital status transitions and psychological distress: longitudinal evidence from a national population sample. Psychological Medicine 29, 381389.

213

Jacob, D., Baldessarini, R., Conwell, Y., Fawcett, J., Horton, L., Meltzer, H., Pfeffer, C., Simon, R., 2003. Practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. American Journal of Psychiatry 160 Supplement. Joung, I., 1997. The relationship between marital status and health. Nederlandse Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde 141, 277282. Kessler, R., Borges, G., Walters, E., 1999. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 56, 617626. Kiernan, K., Cherlin, A., 1999. Parental divorce and partnership dissolution in adulthood: evidence from a British cohort study. Population Studies 53 (2), 3948. Kposowa, A., 2000. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal 525 Mortality Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 54, 254261. Kposowa, A., 2003. Divorce and suicide risk. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57, 993. Leenaars, A., Lester, D., 1995. The changing suicide pattern in Canadian adolescents and youth, compared to their American counterparts. Adolescence 30, 539547. Lester, D., 1994. The protective effect of marriage for suicide in men and women. Italian Journal of Suicidology 4, 8385. Lnnqvist, J., 2000. Psychiatric aspects of suicidal behaviour: depression. In: Hawton, K., Van Heeringen, K. (Eds.), The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp. 107120. Lorant, V., Kunst, E., Huisman, M., Bopp, M., Mackenbach, J., 2005. A European comparative study of marital status and socio-economic inequalities in suicide. Social Sciences and Medicine 60, 24312441. Marriage Act 1961. Attorney General's Department: Canberra. Mastekaasa, A., 2006. Is marriage/cohabitation benecial for young people? Some evidence on psychological distress among Norwegian college students. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 16,149165. Maughan, B., Taylor, A., 2001. Adolescent psychological problems, partnership transitions and adult mental health: an investigation of selection effects. Psychological Medicine 31, 291305. Mclanahan, S., Bumpass, L., 1988. Intergenerational consequences of family disruption. American Journal of Sociology 93, 130152. Moller-Leimkuhler, A., 2002a. Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 71, 19. Moller-Leimkuhler, A., 2002b. The gender gap in suicide and premature death or: why are men so vulnerable? European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 253, 18. Murphy, G., 1998. Why women are less likely than men to commit suicide. Comprehensive Psychiatry 39, 165175. Oliver, J., Reed, C., Katz, B., Haugh, J., 1999. Students' self-reports of helpseeking: the impact of psychological problems, stress, and demographic variables on utilization of formal and informal support. Social Behaviour and Personality 27, 109128. R Development Core Team, 2006. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www. R-project.org Vienna, Austria. Smith, J., Mercy, J., Conn, J., 1988. Marital status and the risk of suicide. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 78, 7880. Snowdon, J., Draper, B., Wyder, M. Age variation in the prevalence of DSM IV disorders in the cases of suicide of middle aged and older persons in Sydney, (submitted for publication). Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B., Gibbon, M., 1996. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV: Non-Patient Edition (SCID-NP). Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York. Stack, S., 1990. Divorce, suicide, and the mass media: an analysis of differential identication, 19481980. Journal of Marriage and the Family 52, 553558. Stack, S., 2000. Suicide: a 15 year review of sociological literature. Part II: Modernization and social integration. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviour 30, 163176. Trovato, F., 1986. The relationship between marital dissolution and suicide: the Canadian case. Journal of Marriage and the Family 48, 341. Trovato, F., 1991. Sex, marital status, and suicide in Canada. Sociological Perspective 34, 427445. Yip, P., Thornburn, J., 2004. Marital status and risk of suicide: experiences from England and Wales. Psychological Reports 94, 401407.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- How Is Extra-Musical Meaning Possible - Music As A Place and Space For Work - T. DeNora (1986)Document12 pagesHow Is Extra-Musical Meaning Possible - Music As A Place and Space For Work - T. DeNora (1986)vladvaidean100% (1)

- AMCAT All in ONEDocument138 pagesAMCAT All in ONEKuldip DeshmukhPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Personality Mischel WalterDocument318 pagesIntroduction To Personality Mischel WalterFlorina Andrei100% (1)

- Introduction To Political ScienceDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Political Sciencecyrene cayananPas encore d'évaluation

- ImpetigoDocument16 pagesImpetigokikimasyhurPas encore d'évaluation

- Workshop 02.1: Restart Controls: ANSYS Mechanical Basic Structural NonlinearitiesDocument16 pagesWorkshop 02.1: Restart Controls: ANSYS Mechanical Basic Structural NonlinearitiesSahil Jawa100% (1)

- Kid Scid 1 PDFDocument92 pagesKid Scid 1 PDFFlorina Andrei60% (5)

- 3018898Document6 pages3018898Florina AndreiPas encore d'évaluation

- SexDocument9 pagesSexFlorina AndreiPas encore d'évaluation

- Sexual MoralityDocument2 pagesSexual MoralityFlorina AndreiPas encore d'évaluation

- Interaction of Media, Sexual Activity & Academic Achievement in AdolescentsDocument6 pagesInteraction of Media, Sexual Activity & Academic Achievement in AdolescentsFlorina AndreiPas encore d'évaluation

- CecetareDocument11 pagesCecetareFlorina AndreiPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 s2.0 S088761770100124X Main PDFDocument16 pages1 s2.0 S088761770100124X Main PDFFlorina AndreiPas encore d'évaluation

- Conversational Maxims and Some Philosophical ProblemsDocument15 pagesConversational Maxims and Some Philosophical ProblemsPedro Alberto SanchezPas encore d'évaluation

- Evidentiary Value of NarcoDocument2 pagesEvidentiary Value of NarcoAdv. Govind S. TeharePas encore d'évaluation

- Pediatric Autonomic DisorderDocument15 pagesPediatric Autonomic DisorderaimanPas encore d'évaluation

- Speech by His Excellency The Governor of Vihiga County (Rev) Moses Akaranga During The Closing Ceremony of The Induction Course For The Sub-County and Ward Administrators.Document3 pagesSpeech by His Excellency The Governor of Vihiga County (Rev) Moses Akaranga During The Closing Ceremony of The Induction Course For The Sub-County and Ward Administrators.Moses AkarangaPas encore d'évaluation

- Quadrotor UAV For Wind Profile Characterization: Moyano Cano, JavierDocument85 pagesQuadrotor UAV For Wind Profile Characterization: Moyano Cano, JavierJuan SebastianPas encore d'évaluation

- Reported SpeechDocument2 pagesReported SpeechmayerlyPas encore d'évaluation

- Storage Emulated 0 Android Data Com - Cv.docscanner Cache How-China-Engages-South-Asia-Themes-Partners-and-ToolsDocument140 pagesStorage Emulated 0 Android Data Com - Cv.docscanner Cache How-China-Engages-South-Asia-Themes-Partners-and-Toolsrahul kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Reported Speech Step by Step Step 7 Reported QuestionsDocument4 pagesReported Speech Step by Step Step 7 Reported QuestionsDaniela TorresPas encore d'évaluation

- An Analysis of The PoemDocument2 pagesAn Analysis of The PoemDayanand Gowda Kr100% (2)

- Faith-Based Organisational Development (OD) With Churches in MalawiDocument10 pagesFaith-Based Organisational Development (OD) With Churches in MalawiTransbugoyPas encore d'évaluation

- Mirza HRM ProjectDocument44 pagesMirza HRM Projectsameer82786100% (1)

- Michel Agier - Between War and CityDocument25 pagesMichel Agier - Between War and CityGonjack Imam100% (1)

- Digital Sytems Counters and Registers: Dce DceDocument17 pagesDigital Sytems Counters and Registers: Dce DcePhan Gia AnhPas encore d'évaluation

- Dr. A. Aziz Bazoune: King Fahd University of Petroleum & MineralsDocument37 pagesDr. A. Aziz Bazoune: King Fahd University of Petroleum & MineralsJoe Jeba RajanPas encore d'évaluation

- Bgs Chapter 2Document33 pagesBgs Chapter 2KiranShettyPas encore d'évaluation

- Spring94 Exam - Civ ProDocument4 pagesSpring94 Exam - Civ ProGenUp SportsPas encore d'évaluation

- ReadingDocument2 pagesReadingNhư ÝPas encore d'évaluation

- WHAT - IS - SOCIOLOGY (1) (Repaired)Document23 pagesWHAT - IS - SOCIOLOGY (1) (Repaired)Sarthika Singhal Sarthika SinghalPas encore d'évaluation

- Ar 2003Document187 pagesAr 2003Alberto ArrietaPas encore d'évaluation

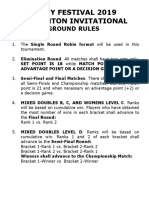

- Ground Rules 2019Document3 pagesGround Rules 2019Jeremiah Miko LepasanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Intrauterine Growth RestrictionDocument5 pagesIntrauterine Growth RestrictionColleen MercadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Far Eastern University-Institute of Nursing In-House NursingDocument25 pagesFar Eastern University-Institute of Nursing In-House Nursingjonasdelacruz1111Pas encore d'évaluation

- Jordana Wagner Leadership Inventory Outcome 2Document22 pagesJordana Wagner Leadership Inventory Outcome 2api-664984112Pas encore d'évaluation

- Physics Syllabus PDFDocument17 pagesPhysics Syllabus PDFCharles Ghati100% (1)

- Framework For Marketing Management Global 6Th Edition Kotler Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument33 pagesFramework For Marketing Management Global 6Th Edition Kotler Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFWilliamThomasbpsg100% (9)