Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Banking Laws

Transféré par

Fame Gonzales PortinCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Banking Laws

Transféré par

Fame Gonzales PortinDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Consolidated Bank and Trust Corp. v. CA + L.C.

Diaz and Company (2003) / Carpio Facts LC Diaz [professional partnership engaged in accounting] opened a savings account with Solidbank. LC Diaz's cashier, Macaraya, filled up two savings deposit slips, and she gave them + passbook to messenger Calapre and instructed him to deposit the money with Solidbank. Calapre presented the deposit slips and passbook to the teller. He left the passbook with Solidbank first as he had to make another deposit at Allied Bank, but when he returned, he was informed that somebody got the passbook. Calapre reported this to Macaraya. Macaraya + Calapre went back to Solidbank with a deposit slip [P200k check]. When Macaraya asked about the passbook, the teller said that someone shorter than Calapre got it. Macaraya reported this matter. The following day, CEO Diaz called Solidbank to stop any transaction using the passbook until the company could open a new account. It was found out that learned that P300k was withdrawn from the account the previous day. The withdrawal slip bore the signatures of two authorized signatories of LC Diaz but they denied signing it. Noel Tamayo received this sum of money. An information for Estafa through Falsification of Commercial Document was filed against one of their messengers (Ilagan) and one Roscoe Verdazola (first time they appeared in the case discussion), but the RTC dismissed the criminal case. LC Diaz demanded the return of their money from Solidbank, but the latter refused and a complaint for recovery of a sum of money was filed against them. However, Solidbank was absolved. RTC applied rules on savings account written on the passbook ["Possession of this book shall raise the presumption of ownership and any payment or payments made by the bank upon the production of the said book and entry therein of the withdrawal shall have the same effect as if made to the depositor personally."] RTC said that the burden of proof shifted to LC Diaz to prove that the signatures are not forged. Also, they applied the rule that the holder of the passport is presumed to be the owner. It was also held that Solidbank did not have any participation in the custody and care of the passbook and as such, their act of allowing the withdrawal was not the proximate cause of the loss. The proximate cause was LC Diaz negligence. As regards the contention that LC Diaz and Solidbank had precautionary procedures (like a secret handshake of sorts) whenever the former withdrew a large sum, RTC pointed out that LC Diaz disregarded this in the past withdrawal. CA, on the other hand, said that the proximate cause of the unauthorized withdrawal is Solidbank's negligence, applying NCC 2176. CA said the 3 elements of QD are present [damages; fault or negligence; connection of cause and effect]. The teller could have called up LC Diaz since the amount being drawn was significant. Proximate cause is teller's failure to call LC Diaz. CA ruled that while LC Diaz was negligent in entrusting its deposits to its messenger and its messenger in leaving the passbook with the teller, Solidbank could not escape liability because of the doctrine of last clear chance. Solidbank could have averted the injury had it called up LC Diaz to verify the withdrawal. RATIO On Solidbank's fiduciary duty under the law SC says that Solidbank is liable for breach of K due to negligence [culpa contractual]. K [savings deposit agreement] between bank and depositor governed by provisions on simple loan; bank is the debtor and depositor is the creditor. Banks are under obligation to treat accounts of depositors with meticulous care [higher than diligence of a good father of a family standard], bearing in mind the fiduciary nature of their relationship. The bank's obligation to observe high standards of integrity and performance is deemed written in every deposit agreement. However, this nature does not convert K from a simple loan to a trust agreement (failure by bank to pay depositor is failure to pay a simple loan only).

Solidbank's breach of K-tual obligation For breach of the savings deposit agreement due to negligence, or culpa contractual, the bank is liable to its depositor. When the passbook is in the possession of Solidbanks tellers during withdrawals, the law imposes an even higher degree of diligence. Likewise, tellers must exercise a high degree of diligence in insuring that they return the passbook only to the depositor or authorized representative. In culpa contractual, once the plaintiff proves a breach of contract, there is a presumption that the defendant was at fault or negligent. The burden is on the defendant to prove that he was not at fault or negligent. In culpa aquiliana, the plaintiff has the burden of proof. Solidbank failed to discharge this burden, after LC Diaz establishing the breach of K-tual obligation. Hence, Solidbank is bound by the negligence of its employees. The defense of exercising required diligence in selecting, supervising employees is NOT a complete defense in culpa contractual, unlike in culpa aquiliana. Proximate cause of unauthorized withdrawal Solidbanks negligence in not returning the passbook to Calapre was the proximate cause. [Definition: cause which, in natural and continuous sequence, unbroken by any efficient intervening cause, produces the injury and without which the result would not have occurred.] RTC said that LC Diaz negligence was the proximate cause. However, SC says LC Diaz was not at fault that the passbook landed in the hands of the impostor. In fact, it was in the possession of the bank while the deposit was being processed. CA said that teller's failure to call LC Diaz was the proximate cause. SC says the bank did not have the duty to call LC Diaz to confirm withdrawal. Doctrine of last clear chance "Where both parties are negligent but the negligent act of one is appreciably later than that of the other, or where it is impossible to determine whose fault or negligence caused the loss, the one who had the last clear opportunity to avoid the loss but failed to do so, is chargeable with the loss." SC DOES NOT APPLY IT HERE. Solidbank is liable for breach of contract due to negligence in the performance of its contractual obligation to LC Diaz. This is a case of culpa contractual, where neither the contributory negligence of the plaintiff nor his last clear chance to avoid the loss, would exonerate the defendant from liability. Since LC Diaz was guilty of contributory negligence, Solidbank's liability should be reduced. Benguet Management v. CA G.R. No. 153571, September 18, 2003 Credit Transactions: Real Estate Mortgage Extra-judicial Foreclosure Venue of Action FACTS: Benguet Management Corporation (BMC) and Keppel Bank Philippines Inc. (KBPI) entered into a Loan Agreement and Mortgage Trust Indenture. For the consideration of Php 190M, BMC mortgaged its properties located in Alaminos, Laguna and Iba, Zambales. BMC defaulted so KBPI filed an application for extra-judicial foreclosure of real estate mortgage first with the Office of theClerk of Court of the Regional Trial Court in Iba and later with the Office of the Clerk of Court of the Regional Trial Court in San Pablo City.

BMC contended that the application should be denied on grounds of wrong remedy and forumshopping. The trial court granted the foreclosure proceedings. ISSUES: W/N KBPI violated the rule against forum-shopping in filing applications for extra-judicial foreclosure of real estate mortgage with both the RTCs in Iba and San Pablo City HELD: Under the Procedure for Extra-Judicial Foreclosure of Mortgage, an extra-judicial foreclosure covering several propertieslocated in different provinces but covering only one indebtedness requires the applicant to pay only one filing fee. This is regardless of the number of properties to be foreclosed. However, the venue of the extra-judicial foreclosure proceedings is the place where each of the mortgaged property is located. The rationale of this rule is that an injunction order of the court is enforceable only within its territorial limits. Therefore, those properties subject to the same mortgage but are located in different provinces are outside the jurisdiction of the trial court. The remedy of the law is to allow the applicant to file separate injunction suits with another court which has jurisdiction over the latter properties. BMC is not guilty of forum-shopping because the remedy provided by law is precisely to file separate injunction suits. PHILIPPINE BANKING CORP. VS. CA, G.R. No. 127469 January 15, 2004 Below this digest is the full text of the case. FACTS: 1. Marcos filed a complaint for a sum of money against Phil. Bank corp. alleging that he made a time deposit on two occasion through Pagsaligan one of the official of the bank in which in his first deposit, a receipt was given to him but in his second deposit, he was given only a letter of certification and when he tried to withdraw from the bank his time deposit to buy a material for his constraction, he was convince by the bank through Pagsaligan to keep his deposit intact and open a domestic letter of credit instead. 2. The BANK required Marcos to give a marginal deposit of 30% of the total amount of the letters of credit. The time deposits of Marcos would secure 70% of the letters of credit. Since Marcos trusted the BANK and Pagsaligan, he signed blank printed forms of the application for the domestic letters of credit, trust receipt agreements and promissory notes and executed three trust receipt agreement. 3. Marcos believe that he and the bank become debtor and creditor of each other and expect that the bank would offset his credit with his time deposit. 4. The bank on there answer denied the claim of marcos and alleged that it is a desperate attempt of marcos to avoid his liability under several trust receipt agreement which is the subject of a criminal complaint and claim that Marcos had a loan to them covered by a promissory notes.

5. The trial court rendered a decision in favor of Marcos and when the petitioner appealed to the court of appeals, it modify the decision of the RTC by reducing the actual damages and deleting the attorneys fees. ISSUE. WHETHER OR NOT THE PETITIONER [sic] ABLE TO PROVE THE PRIVATE RESPONDENTS OUTSTANDING OBLIGATIONS SECURED BY THE ASSIGNMENT OF TIME DEPOSITS. According to the SUPREME COURT, the machine copy of the promissory notes presented by the bank had no evidentiary value, they could easily prove it had they presented the original copy because By the very nature of its business, the BANK should have had in its possession the original copies of the disputed promissory note and the records and ledgers evidencing the offsetting of the loan with the time deposits of Marcos. The BANK inexplicably failed to produce the original copies of these documents. Clearly, the BANK failed to treat the account of Marcos with meticulous care. PNB vs PikeDate: September 20, 2005 Facts: Norman Pike often traveled to and from Japan as a gay entertainer in said country. Sometime in 1991, he opened U.S. Dollar Savings Account with PNB Buendia branch for which he was issued a passbook. The complaint alleged that before Pike left for Japan on 18 March 1993, he kept the passbook inside a cabinet under lock and key, in his home. A few hours after he arrived from Japan, he discovered that some of his valuables were missing including the passbook; that he immediately reported the incident to the police which led to the arrest and prosecution of a certain Mr. Joy Manuel Davasol. Pike also discovered that Davasol made 2 unauthorized withdrawals from his U.S. Dollar Savings Account. Pike went to PNBs Buendia branch and verbally protested the unauthorized withdrawals and likewise demanded the return of the total withdrawn amount of U.S. $7,500.00, on the ground that he never authorized anybody to withdraw from his account as the signatures appearing on the subject withdrawal slips were clearly forgeries. PNB refused to credit said amount back to Pikes U.S. Dollar Savings Account , and instead, the bank wrote him that it exercised due diligence in the handling of said account. Pike filed a case against PNB. PNB, on the other hand, claimed that before Pike went to Japan, he and Davasol went to see PNB AVP Mr. Lorenzo Val and instructed the latter to honor all withdrawals to be made by Davasol. After the loss of Pikes passbook, he allegedly withdraw the balance from his passbook and executed an affidavit promising not to hold responsible the bank and its officers for the withdrawal made. The trial court ruled that the bank is liable for the unauthorized withdrawals. The bank was negligent in the performance of its duties such that unauthorized withdrawals were made in the deposit of Pike. The CA affirmed the findings of the RTC that indeed defendant-appellant PNB was negligent in exercising the diligence required of a business imbued with public interest such as that of the banking industry, however, it modified the rate of interest and award for damages. Issue: WON PNB is liable for the unauthorized withdrawals Held: Yes Ratio A priori, it is quite evident that the petition is anchored on a plea to review or reexamine the factual conclusions reached by the trial court and affirmed by the CA, and for this Court to hold otherwise. Whether: 1) Pikes signatures appearing on the pertinent withdrawal slips used by Joy Manuel Davasol to withdraw the amount of $7,500.00, were forgeries, as found by the trial court and affirmed by the Court of Appeals, or were authentic as claimed by petitioner bank; and2) Pike in fact executed

a waiver absolving petitioner bank from any legal responsibility due to the unauthorized withdrawals, as maintained by petitioner bank, or the paragraph containing said waiver was intercalated by some other person, thus, amounting no waiver at all, as held by the courts a quo. Are questions of fact and not of law. Inexorably, these issues call for an inquiry into the facts and evidence on record. This, as we have so often held, we cannot do. Elementary is the rule that this Court is not the appropriate venue to consider anew the factual issues as it is not a trier of facts, and, it generally does not weigh anew the evidence already passed upon by the Court of Appeals. When this Court is tasked to go over once more the evidence presented by both parties, and analyze, assess and weigh them to ascertain if the trial court and the appellate court were correct in according superior credit to this or that piece of evidence of one party or the other, the Court cannot and will not do the same. Finding no other alternative but to affirm their finding that petitioner PNB negligently allowed the unauthorized withdrawals subject of the case at bar, the instant petition for review must necessarily fail. It bears emphasizing that negligence of banking institutions should never be countenanced. The negligence here lies in the lackadaisical attitude exhibited by employees of PNB in their treatment of respondent Pikes US Dollar Savings Account that resulted in the unauthorized withdrawal of $7,500. Nevertheless, though its employees may be the ones negligent, a banks liability as an obligor is not merely vicarious but primary, as banks are expected to exercise the highest degree of diligence in the selection and supervision of their employees, and having such obligation, this Court cannot ignore the circumstances surrounding the case at bar how the employees of PNB turned their heads, nay, closed their eyes to the suspicious circumstances enfolding the two withdrawals subject of the case at bar. It may even be said that they went out of their ways to disregard standard operating procedures formulated to ensure the security of each and every account that they are handling. PNB does not deny that the withdrawal slips used were in breach of standard operating procedures of banks in the ordinary and usual course of banking operations as testified to by one of its witnesses, Mr. Lorenzo T. Bal. PNBs witness was utterly remiss in protecting the banks client, as well as the bank itself, when he allowed an account holder to make it appear as if he was the one actually withdrawing from an account and actually receiving the withdrawn amount. Ordinarily, banks allow withdrawal by someone who is not the accountholder so long as the account holder authorizes his representative to withdraw and receive from his account by signing on the space provided particularly for such transactions, usually found at the back of withdrawal slips. As fittingly found by the courts a quo, if indeed, respondent Pike signed the withdrawal slips in the presence of Lorenzo Bal, PNBs AVP at its Buendia branch, why did he not call Pikes attention and refer him to the space provided for authorizing representatives to withdraw from and receive the proceeds of such withdrawal? Or, at the very least, sign or initial the same so that he could identify the pre-signed withdrawal slips made by Mr. Pike? By his own testimony, the witness negated the very reason for the banks bizarre accommodation of the alleged verbal request of Pike that he was a valued client. From the aforequoted, it appears that Lorenzo Bal, was not even reasonably familiar with Pike, yet, he was ready, willing and able to accommodate the verbal request of said depositor. Worse still, the witness still approved the withdrawal transaction without asking for any proof of identification for the reason that: 1) Davasol was in possession of a presigned withdrawal slip; and 2) the witness recognized the signature of respondent Pike even after admitting that he did not bother to counter check the signature on the slip with the specimen signature card of Pike and that he met respondent Pike just once so that he cannot seem to recall what the latter looks like. Having admitted that pre-signed withdrawal slips do not constitute the normal procedure with respect to withdrawals by representatives should have already put PNBs employees on guard. Rather than readily validating and permitting said withdrawals, they should have proceeded more cautiously. Clearly, Lorenzo T. Bal, an Assistant Vice President at that, was exceedingly careless in his treatment of respondent Pikes savings account.

From the foregoing, the evidence clearly showed that the bank did not exercise the degree of diligence that it ought to have exercised in dealing with their clients. With banks, the degree of diligence required, contrary to the position of petitioner PNB, is more than that of a good father of a family considering that the business of banking is imbued with public interest due to the nature of their functions. The stability of banks largely depends on the confidence of the people in the honesty and efficiency of banks. Thus, the law imposes on banks a high degree of obligation to treat the accounts of its depositors with meticulous care, always having in mind the fiduciary nature of banking. Section 2 of Republic ActNo. 8791,[25] which took effect on 13 June 2000, makes a categorical declaration that the State recognizes the fiduciary nature of banking that requires high standards of integrity and performance. Issue: WON the award of damages was proper Held: Yes Ratio: The award of moral and exemplary damages is left to the sound discretion of the court, and if such discretion is well exercised, as in this case, it will not be disturbed on appeal. An award of moral damages would require, firstly, evidence of besmirched reputation, or physical, mental or psychological suffering sustained by the claimant; secondly, a culpable act or omission factually established; thirdly, proof that the wrongful act or omission of the defendant is the proximate cause of the damages sustained by the claimant; and fourthly, that the case is predicated on any of the instances expressed or envisioned by Articles 2219 and 2220 of the Civil Code. Specifically, in culpa contractual or breach of contract, as here, moral damages are recoverable only if the defendant has acted fraudulently or in bad faith, or is found guilty of gross negligence amounting to bad faith,[38]or in wanton disregard of his contractual obligations. Verily, the breach must be wanton, reckless, malicious, or in bad faith, oppressive or abusive. There is no reason to disturb the trial courts finding of the banks employees negligence in their treatment of Pikes account. In the case on hand, the Court of Appeals sustained, and rightly so, that an award of moral damages is warranted. For, as found by said appellate court, citing the case of Prudential Bank v. Court of Appeals, the banks negligence is a result of lack of due care and caution required of managers and employees of a firm engaged in so sensitive and demanding business, as banking, hence, the award of P20,000.00 as moral damages, is proper. The award of exemplary damages is also proper as a warning to petitioner PNB and all concerned not to recklessly disregard their obligation to exercise the highest and strictest diligence in serving their depositors. Finally, the grant of exemplary damages entitles respondent Pike the award of attorney's fees in the amount of P20,000.00 and the award of P10,000.00 for litigation expenses.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Don Martin Tax CaseDocument13 pagesDon Martin Tax CaseFame Gonzales PortinPas encore d'évaluation

- Commercial Rev 1Document139 pagesCommercial Rev 1Fame Gonzales PortinPas encore d'évaluation

- Pub Cor CasesDocument18 pagesPub Cor CasesFame Gonzales PortinPas encore d'évaluation

- Special Penal LawsDocument64 pagesSpecial Penal LawsFame Gonzales PortinPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- NIL - Interpretation and NegotiationDocument7 pagesNIL - Interpretation and NegotiationRem SerranoPas encore d'évaluation

- Prelim Examination Business TaxDocument16 pagesPrelim Examination Business Taxmikheal beyberPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract LAW ExamDocument10 pagesContract LAW ExamSubhan SoomroPas encore d'évaluation

- UNION BANK V. SANTIBANEZ Case Digest - Notes of My Legal AdventuresDocument2 pagesUNION BANK V. SANTIBANEZ Case Digest - Notes of My Legal AdventuresMadam JudgerPas encore d'évaluation

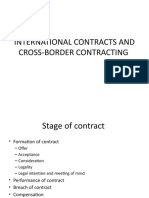

- International Contracts and Cross-Border ContractingDocument26 pagesInternational Contracts and Cross-Border ContractingArpit Goyal100% (1)

- Forform Vs PNRDocument1 pageForform Vs PNRBrod LenamingPas encore d'évaluation

- 18 JLegal Stud 105Document35 pages18 JLegal Stud 105mfgomezbazanPas encore d'évaluation

- 232 Uy Ek Liong V Meer Castillo GR 176425 June5 2013Document2 pages232 Uy Ek Liong V Meer Castillo GR 176425 June5 2013Joseff Anthony Fernandez50% (2)

- Using The LCD5511 Keypad: 3. Number PadDocument12 pagesUsing The LCD5511 Keypad: 3. Number PadAlejo CdnPas encore d'évaluation

- A Fresh Look at The Humble Contract BoilerplateDocument24 pagesA Fresh Look at The Humble Contract Boilerplatemmartin_673942Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sec - Ogc Opinion No 11-30 & 38Document6 pagesSec - Ogc Opinion No 11-30 & 38Mary Anne R. BersotoPas encore d'évaluation

- Acca D Formation of A CompanyDocument12 pagesAcca D Formation of A CompanyNana AmalinaPas encore d'évaluation

- Tuazon Vs Heirs of BartolomeDocument1 pageTuazon Vs Heirs of BartolomeGalilee RomasantaPas encore d'évaluation

- PMBR Flash Cards - Contracts - 2007Document142 pagesPMBR Flash Cards - Contracts - 2007jackojidemasiadoPas encore d'évaluation

- Contract Between Club and Amateur PlayerDocument3 pagesContract Between Club and Amateur Playeranil100% (1)

- Town of Holly Ridge ComplaintDocument37 pagesTown of Holly Ridge ComplaintNicholas AzizPas encore d'évaluation

- Mid's Labor Relations RviewerDocument10 pagesMid's Labor Relations RviewerAMIDA ISMAEL. SALISAPas encore d'évaluation

- Civil Complaint-Specific Performance With Damages Damages-Antoinette GargaritanoDocument9 pagesCivil Complaint-Specific Performance With Damages Damages-Antoinette GargaritanoRobocop Torrijos100% (3)

- Quiz 1Document7 pagesQuiz 1nichols greenPas encore d'évaluation

- Extrajudicial Settlement of The Intestate Estate of The Late Anna LazaroDocument4 pagesExtrajudicial Settlement of The Intestate Estate of The Late Anna LazaroPDEA MastermasonPas encore d'évaluation

- First Batch - SMC Union Vs BersamiraDocument2 pagesFirst Batch - SMC Union Vs BersamiraAngelReaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sheldon Bradt Primary Analysis and GenealogyDocument6 pagesSheldon Bradt Primary Analysis and Genealogyapi-339882828Pas encore d'évaluation

- Module 4 - Obligations of The Vendee and Actions For Breach of ContractDocument10 pagesModule 4 - Obligations of The Vendee and Actions For Breach of ContractYess poooPas encore d'évaluation

- 5 Credit InvestigationDocument4 pages5 Credit InvestigationLansing0% (1)

- Implying Terms Into A ContractDocument5 pagesImplying Terms Into A ContractVMPas encore d'évaluation

- CRC Appointment Letter Janaki RamanDocument5 pagesCRC Appointment Letter Janaki Ramanh_madhankumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Merchant BankeingDocument2 pagesMerchant BankeingRajjan PrasadPas encore d'évaluation

- Negotiable Instruments LawDocument72 pagesNegotiable Instruments LaworlandoPas encore d'évaluation

- PVL2601 Case SummaryDocument26 pagesPVL2601 Case SummarydjgtmmkhrzPas encore d'évaluation

- Waiver or Rights Template 1Document2 pagesWaiver or Rights Template 1Laurence Erex GomezPas encore d'évaluation