Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Vector Model For Orbital Angular Momentum

Transféré par

Agrupación Astronomica de AlicanteTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Vector Model For Orbital Angular Momentum

Transféré par

Agrupación Astronomica de AlicanteDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Quantized Angular Momentum

In the process of solving the Schrodinger equation for the hydrogen atom, it is found

that the orbital angular momentum is quantized according to the relationship:

It is a characteristic of angular momenta in quantum mechanics that the magnitude of

the angular momentum in terms of the orbital quantum number is of the form

and that the z-component of the angular momentum in terms of the magnetic quantum

number takes the form

This general form applies to orbital angular momentum, spin angular momentum, and

the total angular momentum for an atomic system. The relationship between the

magnitude of the angular momentum and its projection along any direction is space is

often visualized in terms of a vector model.

Total Angular Momentum

When the orbital angular momentum and spin angular momentum are coupled, the total

angular momentum is of the general form for quantized angular momentum

where the total angular momentum quantum number is

This gives a z-component of angular momentum

This kind of coupling gives an even number of angular momentum levels, which is

consistent with the multiplets seen in anomalous Zeeman effects such as that of sodium.

As long as external interactions are not extremely strong, the total angular momentum

of an electron can be considered to be conserved and j is said to be a "good quantum

number". This quantum number is used to characterize the splitting of atomic energy

levels, such as the spin-orbit splitting which leads to the sodium doublet.

Vector Model for angular momentum

The orbital angular momentum for an atomic electron can be visualized in terms of a

vector model where the angular momentum vector is seen as precessing about a

direction in space. While the angular momentum vector has the magnitude shown, only

a maximum of l units can be measured along a given direction, where l is the orbital

quantum number.

Since there is a magnetic moment associated with the orbital angular momentum, the

precession can be compared to the precession of a classical magnetic moment caused by

the torque exerted by a magnetic field. This precession is called Larmor precession and

has a characteristic frequency called the Larmor frequency

While called a "vector", it is a special kind of vector because it's projection along a

direction in space is quantized to values one unit of angular momentum apart. The

diagram shows that the possible values for the "magnetic quantum number" ml for l=2

can take the values

= -2, -1, 0, 1, 2

or, in general

= -l, -l+1,..., l-1, l .

Vector Model for Total Angular Momentum

When orbital angular momentum L and electron spin angular momentum S are

combined to produce the total angular momentum of an atomic electron, the

combination process can be visualized in terms of a vector model. Both the orbital and

spin angular momentua are seen as precessing about the direction of the total angular

momentum J. This diagram can be seen as describing a single electron, or multiple

electrons for which the spin and orbital angular momenta have been combined to

produce composite angular momenta S and L respectively. In so doing, one has made

assumptions about the coupling of the angular momenta which are described by the L-S

coupling scheme which is appropriate for light atoms with relatively small external

magnetic fields.

The combination is a special kind of vector addition as is illustrated for the single

electron case l=1 and s=1/2. As in the case of the orbital angular momentum alone, the

projection of the total angular momentum along a direction in space is quantized to

values differeing by one unit of angular momentum.

Angular Momentum in a Magnetic Field

Once you have combined orbital and spin angular momenta according to the vector

model, the resulting total angular momentum can be visuallized as precessing about any

externally applied magnetic field.

This is a useful model for dealing with interactions such as the Zeeman effect in

sodium. The magnetic energy contribution is proportional to the component of total

angular momentum along the direction of the magnetic field, which is usually defined

as the z-direction.

The z-component of angular momentum is quantized in values one unit apart, so for the

upper level of the sodium doublet with j=3/2, the vector model gives the splitting

shown.

Even with the vector model, the determination of the magnitude of the Zeeman spliting

is not trivial since the directions of S and L ar constantly changing as they precess about

J. This problem is handled with the Lande' g-factor.

This treatment of the angular momentum is appropriate for weak external magnetic

fields where the coupling between the spin and orbital angular momenta can be

presumed to be stronger than the coupling to the external field. This can be visualized

with the help of a vector model of total angular momentum. If the external field is very

strong, then it can decouple the spin and orbital angular momenta. This strong field case

is called the Paschen-Back effect and leads to different patterns of splitting of the

energy levels.

Electron Spin

An electron spin s = 1/2 is an intrinsic property of

electrons. Electrons have intrinsic angular momentum

characterized by quantum number 1/2. In the pattern of

other quantized angular momenta, this gives total angular

momentum

The resulting fine structure which is observed corresponds

to two possibilities for the z-component of the angular

momentum.

Spin "up" and "down"

allows two electrons for This causes an energy splitting because of the magnetic

each set of spatial quantum moment of the electron

numbers.

Electron Spin

Two types of experimental evidence which arose in the 1920s suggested an additional

property of the electron. One was the closely spaced splitting of the hydrogen spectral

lines, called fine structure. The other was the Stern-Gerlach experiment which showed

in 1922 that a beam of silver atoms directed through an inhomogeneous magnetic field

would be forced into two beams. Both of these experimental situations were consistent

with the possession of an intrinsic angular momentum and a magnetic moment by

individual electrons. Classically this could occur if the electron were a spinning ball of

charge, and this property was called electron spin.

Quantization of angular momentum had already arisen for orbital angular momentum,

and if this electron spin behaved the same way, an angular momentum quantum number

s = 1/2 was required to give just two states. This intrinsic electron property gives:

Electron Intrinsic Angular Momentum

Experimental evidence like the hydrogen fine structure and the Stern-Gerlach

experiment suggest that an electron has an intrinsic angular momentum, independent of

its orbital angular momentum. These experiments suggest just two possible states for

this angular momentum, and following the pattern of quantized angular momentum, this

requires an angular momentum quantum number of 1/2.

With this evidence, we say that the electron has spin 1/2. An angular momentum and a

magnetic moment could indeed arise from a spinning sphere of charge, but this classical

picture cannot fit the size or quantized nature of the electron spin. The property called

electron spin must be considered to be a quantum concept without detailed classical

analogy. The quantum numbers associated with electron spin follow the characteristic

pattern:

Electron Spin Magnetic Moment

Since the electron displays an intrinsic angular momentum, one might expect a

magnetic moment which follows the form of that for an electron orbit. The z-component

of magnetic moment associated with the electron spin would then be expected to be

but the measured value turns out to be about twice that. The measured value is written

where g is called the gyromagnetic ratio and the electron spin g-factor has the value g =

2.00232 and g=1 for orbital angular momentum. The precise value of g was predicted

by relativistic quantum mechanics in the Dirac equation and was measured in the Lamb

shift experiment. A natural constant which arises in the treatment of magnetic effects is

called the Bohr magneton. The magnetic moment is usually expressed as a multiple of

the Bohr magneton.

The electron spin magnetic moment is important in the spin-orbit interaction which

splits atomic energy levels and gives rise to fine structure in the spectra of atoms. The

electron spin magnetic moment is also a factor in the interaction of atoms with external

magnetic fields (Zeeman effect).

The term "electron spin" is not to be taken literally in the classical sense as a description

of the origin of the magnetic moment described above. To be sure, a spinning sphere of

charge can produce a magnetic moment, but the magnitude of the magnetic moment

obtained above cannot be reasonably modeled by considering the electron as a spinning

sphere. High energy scattering from electrons shows no "size" of the electron down to a

resolution of about 10-3 fermis, and at that size a preposterously high spin rate of some

1032 radian/s would be required to match the observed angular momentum.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Zeeman and Paschen-Back EffectDocument12 pagesZeeman and Paschen-Back EffectKamanpreet Singh100% (1)

- Physics 1922 – 1941: Including Presentation Speeches and Laureates' BiographiesD'EverandPhysics 1922 – 1941: Including Presentation Speeches and Laureates' BiographiesPas encore d'évaluation

- Atomic Structure and Atomic SpectraDocument37 pagesAtomic Structure and Atomic SpectraAniSusiloPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter # 21 Nuclear PhysicsDocument7 pagesChapter # 21 Nuclear PhysicsAsif Rasheed RajputPas encore d'évaluation

- Nuclear PhysicsDocument20 pagesNuclear PhysicsShubh GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Larmor PrecessionDocument2 pagesLarmor PrecessionRanojit barmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Object:: Gamma RaysDocument13 pagesObject:: Gamma Raysm4nmoPas encore d'évaluation

- (#3) Direct, Indirect, Ek Diagram, Effective Mass-1Document6 pages(#3) Direct, Indirect, Ek Diagram, Effective Mass-1zubairPas encore d'évaluation

- A Review of Magneto-Optic Effects and Its Application: Taskeya HaiderDocument8 pagesA Review of Magneto-Optic Effects and Its Application: Taskeya HaiderkanchankonwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Richardson EqnDocument3 pagesRichardson EqnagnirailwaysPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit - IV Semiconductor Physics: Prepared by Dr. T. KARTHICK, SASTRA Deemed UniversityDocument21 pagesUnit - IV Semiconductor Physics: Prepared by Dr. T. KARTHICK, SASTRA Deemed UniversityMamidi Satya narayana100% (1)

- E by M Using Magnetron ValveDocument7 pagesE by M Using Magnetron ValvekanchankonwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Quantum MechanicsDocument29 pagesQuantum MechanicsHasan ZiauddinPas encore d'évaluation

- Free Electron TheoryDocument17 pagesFree Electron TheoryBijay SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- La Preuve de ThomsonDocument11 pagesLa Preuve de ThomsonChadiChahid100% (1)

- Particle PhysicsDocument16 pagesParticle PhysicsBoneGrisslePas encore d'évaluation

- Study Gamma Spectra Using Scintillation CounterDocument10 pagesStudy Gamma Spectra Using Scintillation CounterHelpUnlimitedPas encore d'évaluation

- ZeemanDocument15 pagesZeemanritik12041998Pas encore d'évaluation

- Atom LightDocument23 pagesAtom LightGharib MahmoudPas encore d'évaluation

- Magnetic HysteresisDocument10 pagesMagnetic HysteresisHarsh PurwarPas encore d'évaluation

- InterferenceDocument19 pagesInterferenceMuhammad AliPas encore d'évaluation

- Physics Question Bank-2Document35 pagesPhysics Question Bank-2Ghai karanvirPas encore d'évaluation

- 6 Intrinsic Semiconductor-1Document12 pages6 Intrinsic Semiconductor-1api-462620165Pas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 8: Band Theory of Solids Concept of Free Electron Theory: Hour 1Document25 pagesChapter 8: Band Theory of Solids Concept of Free Electron Theory: Hour 1Vivek kapoorPas encore d'évaluation

- 4, 1971 Second-Harmonic Radiation From SurfacesDocument17 pages4, 1971 Second-Harmonic Radiation From SurfacesSteven BrooksPas encore d'évaluation

- Magnetoresistance Experiment Lab ManualDocument8 pagesMagnetoresistance Experiment Lab ManualKomal DahiyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Diffusion PlasmaDocument34 pagesDiffusion PlasmaPriyanka Lochab100% (1)

- B. TechDocument36 pagesB. TechOjaswi GahoiPas encore d'évaluation

- Geiger M Uller Counter (GM Counter)Document26 pagesGeiger M Uller Counter (GM Counter)AviteshPas encore d'évaluation

- Electrostatics CH2 Part - 2Document24 pagesElectrostatics CH2 Part - 2Rishab SharmaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lecture 4 Wavefunction NewDocument53 pagesLecture 4 Wavefunction NewkedirPas encore d'évaluation

- Helium Neon LaserDocument10 pagesHelium Neon LaserSai SridharPas encore d'évaluation

- LASERDocument17 pagesLASERKomal Saeed100% (1)

- Energy Bands For Electrons in Crystals (Kittel Ch. 7)Document39 pagesEnergy Bands For Electrons in Crystals (Kittel Ch. 7)sabhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Differential Calculus Unit III - Beta and Gamma FunctionsDocument27 pagesDifferential Calculus Unit III - Beta and Gamma FunctionsSatuluri Satyanagendra RaoPas encore d'évaluation

- UNIT - 4 - ppt-1Document49 pagesUNIT - 4 - ppt-1Neha YarapothuPas encore d'évaluation

- GM Counter ManualDocument29 pagesGM Counter ManualJz NeilPas encore d'évaluation

- Stewart GeeDocument11 pagesStewart GeeJohnPas encore d'évaluation

- Atomic StructureDocument3 pagesAtomic StructureRoNPas encore d'évaluation

- Models - Plasma.drift Diffusion TutorialDocument14 pagesModels - Plasma.drift Diffusion TutorialbkmmizanPas encore d'évaluation

- Dual Nature of Matter and Radiation MainsDocument14 pagesDual Nature of Matter and Radiation MainsVigneshRamakrishnanPas encore d'évaluation

- Calculation of Planck Constant Using Photocell: Name: Shivam Roll No.: 20313127Document13 pagesCalculation of Planck Constant Using Photocell: Name: Shivam Roll No.: 20313127shivamPas encore d'évaluation

- Thermal Physics Lecture 13Document7 pagesThermal Physics Lecture 13OmegaUserPas encore d'évaluation

- M.SC - pHYSICS - Electrodynamics and Plasma Physics - Paper XVDocument232 pagesM.SC - pHYSICS - Electrodynamics and Plasma Physics - Paper XVTyisil RyanPas encore d'évaluation

- Magnetic Field of CurrentsDocument48 pagesMagnetic Field of Currentsnamitjain98Pas encore d'évaluation

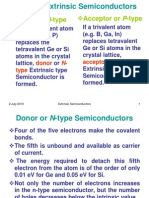

- Extrinsic SemiconductorsDocument28 pagesExtrinsic SemiconductorsSahil AhujaPas encore d'évaluation

- Vicker Hardness TesterDocument4 pagesVicker Hardness TesterVijayakumar mPas encore d'évaluation

- Magnetic Hysteresis: Experiment-164 SDocument13 pagesMagnetic Hysteresis: Experiment-164 SChandra Prakash JainPas encore d'évaluation

- L (17) Nuc-IIDocument11 pagesL (17) Nuc-IIabdulbaseer100% (1)

- Nano SuperconductivityDocument26 pagesNano Superconductivity2018 01403Pas encore d'évaluation

- 2 Alternating CurrentsDocument43 pages2 Alternating CurrentsHarshita KaurPas encore d'évaluation

- SemiconductorsDocument37 pagesSemiconductorsANSHU RAJPas encore d'évaluation

- Unit 2 Absorption in SemiconductorsDocument13 pagesUnit 2 Absorption in SemiconductorsKapilkoundinya NidumoluPas encore d'évaluation

- Dielectric Properties of SolidsDocument40 pagesDielectric Properties of SolidsHannan MiahPas encore d'évaluation

- Physics Lab IIDocument61 pagesPhysics Lab IIhemanta gogoiPas encore d'évaluation

- Physics ProjDocument21 pagesPhysics ProjPunya SuranaPas encore d'évaluation

- Coiled Tubing For Downhole ProcessDocument10 pagesCoiled Tubing For Downhole ProcessCristian BarbuceanuPas encore d'évaluation

- 18,21. Naidian CatalogueDocument31 pages18,21. Naidian CatalogueTaQuangDucPas encore d'évaluation

- What Is Physical GeologyDocument25 pagesWhat Is Physical GeologyMelanyPas encore d'évaluation

- Nba Sar B.tech. Electronics UgDocument171 pagesNba Sar B.tech. Electronics UgSaurabh BhisePas encore d'évaluation

- R12 Period-End Procedures For Oracle Financials E-Business Suite Document 961285Document3 pagesR12 Period-End Procedures For Oracle Financials E-Business Suite Document 961285Ravi BirhmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Assist. Prof. DR - Thaar S. Al-Gasham, Wasit University, Eng. College 136Document49 pagesAssist. Prof. DR - Thaar S. Al-Gasham, Wasit University, Eng. College 136Hundee HundumaaPas encore d'évaluation

- Notice No.8: Rules and Regulations For TheDocument40 pagesNotice No.8: Rules and Regulations For TherickPas encore d'évaluation

- ManualDocument14 pagesManualnas_hoPas encore d'évaluation

- Conventional Smoke DetectorDocument1 pageConventional Smoke DetectorThan Htike AungPas encore d'évaluation

- Especificaciones Discos de Embrague Transmision - Cat 140HDocument6 pagesEspecificaciones Discos de Embrague Transmision - Cat 140HSergio StockmansPas encore d'évaluation

- Sustainable Transport Development in Nepal: Challenges and StrategiesDocument18 pagesSustainable Transport Development in Nepal: Challenges and StrategiesRamesh PokharelPas encore d'évaluation

- Maintenance Manual: Models 7200/7300/7310 Reach-Fork TrucksDocument441 pagesMaintenance Manual: Models 7200/7300/7310 Reach-Fork TrucksMigue Angel Rodríguez Castro100% (2)

- Boom and Trailer Mounted Boom Annual Inspection Report PDFDocument1 pageBoom and Trailer Mounted Boom Annual Inspection Report PDFlanza206Pas encore d'évaluation

- Acopos User's ManualDocument171 pagesAcopos User's ManualKonstantin Gavrilov100% (1)

- SPE143315-Ultrasound Logging Techniques For The Inspection of Sand Control Screen IntegrityDocument18 pagesSPE143315-Ultrasound Logging Techniques For The Inspection of Sand Control Screen IntegrityYovaraj KarunakaranPas encore d'évaluation

- Ibm Lenovo Whistler Rev s1.3 SCHDocument52 pagesIbm Lenovo Whistler Rev s1.3 SCH1cvbnmPas encore d'évaluation

- 7 Inch Liner Cementing ProgramDocument44 pages7 Inch Liner Cementing ProgramMarvin OmañaPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Oil RigsDocument25 pagesIntroduction To Oil RigsballasreedharPas encore d'évaluation

- USBN Bahasa Inggris 2021Document6 pagesUSBN Bahasa Inggris 2021Indah timorentiPas encore d'évaluation

- Final Page Size: A5 (148mm X 210mm)Document20 pagesFinal Page Size: A5 (148mm X 210mm)RJ BevyPas encore d'évaluation

- CS20 Instruction Manual: Inverted Vertical Turning CellDocument83 pagesCS20 Instruction Manual: Inverted Vertical Turning CellHenryPas encore d'évaluation

- Multisite ErpDocument5 pagesMultisite ErparavindhsekarPas encore d'évaluation

- EMF Test Report: Ericsson Street Macro 6701 B261 (FCC) : Rapport Utfärdad Av Ackrediterat ProvningslaboratoriumDocument13 pagesEMF Test Report: Ericsson Street Macro 6701 B261 (FCC) : Rapport Utfärdad Av Ackrediterat Provningslaboratoriumiogdfgkldf iodflgdfPas encore d'évaluation

- Design and Development of Swashplate-Less HelicopterDocument68 pagesDesign and Development of Swashplate-Less HelicopterNsv DineshPas encore d'évaluation

- VP Director Finance Controller in Washington DC Resume Brenda LittleDocument2 pagesVP Director Finance Controller in Washington DC Resume Brenda LittleBrendaLittlePas encore d'évaluation

- Tds G. Beslux Tribopaste L-2-3 S (26.03.09)Document1 pageTds G. Beslux Tribopaste L-2-3 S (26.03.09)Iulian BarbuPas encore d'évaluation

- Python Question Paper Mumbai UnivercityDocument5 pagesPython Question Paper Mumbai UnivercityRahul PawarPas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Mechanics Tutorial Question BankDocument13 pagesEngineering Mechanics Tutorial Question Bankrajeev_kumar365Pas encore d'évaluation

- NHA 2430 Design Analysis Reporting FEADocument7 pagesNHA 2430 Design Analysis Reporting FEAASIM RIAZPas encore d'évaluation

- Construction Methodology for La Vella ResidencesDocument16 pagesConstruction Methodology for La Vella ResidencesEugene Luna100% (1)

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseD'EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (69)

- Quantum Physics: What Everyone Needs to KnowD'EverandQuantum Physics: What Everyone Needs to KnowÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (48)

- Summary and Interpretation of Reality TransurfingD'EverandSummary and Interpretation of Reality TransurfingÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)

- Quantum Spirituality: Science, Gnostic Mysticism, and Connecting with Source ConsciousnessD'EverandQuantum Spirituality: Science, Gnostic Mysticism, and Connecting with Source ConsciousnessÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (6)

- The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern MysticismD'EverandThe Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern MysticismÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (500)

- The Physics of God: How the Deepest Theories of Science Explain Religion and How the Deepest Truths of Religion Explain ScienceD'EverandThe Physics of God: How the Deepest Theories of Science Explain Religion and How the Deepest Truths of Religion Explain ScienceÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (23)

- Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the VoidD'EverandPacking for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the VoidÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1395)

- Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics AstrayD'EverandLost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics AstrayÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (125)

- A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black HolesD'EverandA Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black HolesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (2193)

- Quantum Physics for Beginners Who Flunked Math And Science: Quantum Mechanics And Physics Made Easy Guide In Plain Simple EnglishD'EverandQuantum Physics for Beginners Who Flunked Math And Science: Quantum Mechanics And Physics Made Easy Guide In Plain Simple EnglishÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (18)

- Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside ParsonsD'EverandStrange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside ParsonsÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (94)

- Midnight in Chernobyl: The Story of the World's Greatest Nuclear DisasterD'EverandMidnight in Chernobyl: The Story of the World's Greatest Nuclear DisasterÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (409)

- The Magick of Physics: Uncovering the Fantastical Phenomena in Everyday LifeD'EverandThe Magick of Physics: Uncovering the Fantastical Phenomena in Everyday LifePas encore d'évaluation

- The End of Everything: (Astrophysically Speaking)D'EverandThe End of Everything: (Astrophysically Speaking)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (155)

- In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat: Quantum Physics and RealityD'EverandIn Search of Schrödinger’s Cat: Quantum Physics and RealityÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (380)

- Too Big for a Single Mind: How the Greatest Generation of Physicists Uncovered the Quantum WorldD'EverandToo Big for a Single Mind: How the Greatest Generation of Physicists Uncovered the Quantum WorldÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (8)

- Paradox: The Nine Greatest Enigmas in PhysicsD'EverandParadox: The Nine Greatest Enigmas in PhysicsÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (57)

- Bedeviled: A Shadow History of Demons in ScienceD'EverandBedeviled: A Shadow History of Demons in ScienceÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)

- The Holographic Universe: The Revolutionary Theory of RealityD'EverandThe Holographic Universe: The Revolutionary Theory of RealityÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (75)

- The 60 Minute Quantum Physics Book: Science Made Easy For Beginners Without Math And In Plain Simple EnglishD'EverandThe 60 Minute Quantum Physics Book: Science Made Easy For Beginners Without Math And In Plain Simple EnglishÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (4)

- Starry Messenger: Cosmic Perspectives on CivilizationD'EverandStarry Messenger: Cosmic Perspectives on CivilizationÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (158)

- Black Holes: The Key to Understanding the UniverseD'EverandBlack Holes: The Key to Understanding the UniverseÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (13)

- The Sounds of Life: How Digital Technology Is Bringing Us Closer to the Worlds of Animals and PlantsD'EverandThe Sounds of Life: How Digital Technology Is Bringing Us Closer to the Worlds of Animals and PlantsÉvaluation : 5 sur 5 étoiles5/5 (5)