Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

5 Reason and Experience

Transféré par

Conan AlanDescription originale:

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

5 Reason and Experience

Transféré par

Conan AlanDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

RATIONALISTS AND EMPIRICISTS By Dr Peter Critchley 2011

Critchley, P., 2011. Rationalists and Empiricits. [e-book] Available through: Academia website <http://independent.academia. Edu/PeterCritchley/Papers

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy which concerns what is known and how is it known. The rationalists argue that the acquisition of knowledge comes primarily through the use of reason. The empiricists argue knowledge is acquired mainly as a result of experience gained through the senses. It would be no exaggeration to claim that the history of Western philosophy is characterised by this dualism of reason and experience, deciding whether one or the other is the foundational principle of knowledge. This has been the principal controversy between two extremely influential philosophical schools - rationalism and empiricism. There are three key distinctions which elucidate just what is at stake in this clash between rationalist and empiricist theories of knowledge.

1) a priori vs a posteriori A priori knowledge refers to something that is knowable without reference to experience, that is, without the need for any empirical investigation of the world. '10 - 6 = 4' is known a priori there is no need to investigate the world to establish its truth. A posteriori knowledge requires empirical investigation. The statement 'grass is green' is an a posteriori truth that needs to be verified by finding a patch of grass and determining its colour.

2) analytic vs synthetic An analytic proposition does not require any more information than is contained in the meanings of the terms involved. The truth of the statement 'My brothers wife is my sister-in-law is self-evidently true on account of understanding the meaning and relation of the words used. A synthetic statement requires more information than is contained in the statement. 'My sister-in-law has pink hair brings together (synthesizes) different concepts and thus provides significant information. To determine whether the statement is true or not requires empirical observation of my sister-in-laws hair to establish its colour. 3)necessary vs contingent A necessary truth is one that could not be otherwise - it must be true in any circumstances and in all possible worlds. A contingent truth is true but might not have been true if circumstances had been different. Thus, the statement 'Most Welsh men sing well' is contingent. Whether it is true or not depend on how well most Welsh men sing. By contrast, if it is true that all Welsh men sing well and that Bryn is a Welsh man, then it is necessarily true (a matter of logic, in this instance) that Bryn sings well. The analytic/synthetic distinction originates in the work of Immanuel Kant. In the Critique of Pure Reason Kant is concerned to demonstrate that there are certain concepts or categories of thought - substance and causation, for instance - which cannot be discovered empirically from the world but which are required in order to make sense of the world. Kant proceeds to delineate the nature and justification of these categories or concepts and of the synthetic a priori knowledge that stems from them. The tripartite theory of knowledge

These dualisms should not be taken as an either/or opposition between rationalism and empiricism. There would appear to be a clear congruity between the terms. If true, an analytic statement is necessarily true and therefore is known a priori; if true, a synthetic proposition is contingently true and is therefore known a posteriori. However, this alignment is too tidy. The principal difference between rationalists and empiricists lies in the way that they line up their terms. Thus rationalists set out to demonstrate the truth of synthetic a priori statements that significant or meaningful facts about the world can be discovered by rational means without empirical observation. In contrast, empiricists set out to demonstrate that apparently a priori facts are in fact analytic statements. As in mathematics, 1 + 7 = 8. The field of mathematics has been the battleground where empiricists and rationalists have most often come to blows. Going back to Plato, mathematics is the paradigm of knowledge within the rationalist tradition, presenting an abstract realm of objects which are capable of being known by the use of reason alone. Empiricists hit back, either demonstrating that mathematical facts are essentially analytic or trivial or denying that such facts can be known in this manner. The former route typically takes the form of arguing that what are purported to be the abstract facts of mathematics are actually human constructs and that therefore mathematical reasoning is ultimately a matter of convention. This is not discovery and truth but consensus and proof. Mathematics has not a foot to stand upon which is not purely metaphysical (Thomas de Quincey 1830). European rivalries The British empiricists of the 17th and 18th centuries - Locke, Berkeley and Hume - are typically ranged against their Continental 'rivals', the rationalists Descartes, Leibniz and Spinoza. There is value in this division, but the substance of the points at issue cannot be apprehended in outline, only in the detailed investigation of the philosophers involved. An outline is a handy peg on which to hang complex arguments. Serious treatment means going beyond

simple divisions and categorizations. The philosopher considered to be the founder of rationalism, Descartes, is not at all averse to empirical inquiry. Locke, who considered experience to be the basis of knowledge, makes many rationalist arguments concerning intellectual insight or intuition.

Alternatives to foundationalism For all of these differences, rationalists and empiricists are in agreement that there is some basis on which our knowledge is founded. For rationalists it is reason, for empiricists it is experience. The empiricist Scottish philosopher David Hume can criticize Descartes for his attempt to find a foundation for rational certainty on the basis of which all our knowledge could be corroborated, including the truthfulness of our senses. However, in making this criticism, Hume does not deny that the possibility of finding any basis, simply Descartes view that this foundation can exclude the common experience and the natural systems of belief of human beings. Both rationalism and empiricism are essentially foundationalist. Other approaches discard this basic assumption. Coherentism conceives knowledge to be an interlocking mesh of beliefs, the strands of which support each other to form a coherent body or structure. This body or structure lacks a single foundation, hence the coherentist slogan: 'every argument needs premises, but there is nothing that is the premise of every argument.'

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Socratic Seminar: A Declaration of Independence: Developed by Maureen FestiDocument9 pagesThe Socratic Seminar: A Declaration of Independence: Developed by Maureen FestiConan AlanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

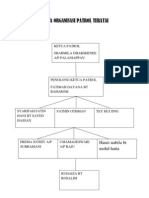

- Carta Organisasi Patrol Teratai: Ketua Patrol Sharmila Dharshenee A/P PalaniappanDocument1 pageCarta Organisasi Patrol Teratai: Ketua Patrol Sharmila Dharshenee A/P PalaniappanConan AlanPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- ERRORS Wong BruneiDocument18 pagesERRORS Wong BruneiConan AlanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Advantages, Disadvantages, and Applications of ConstructivismDocument16 pagesAdvantages, Disadvantages, and Applications of ConstructivismConan AlanPas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- Brace Map - Part To WholeDocument1 pageBrace Map - Part To WholeConan AlanPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Lesson 1 Genma MathDocument9 pagesLesson 1 Genma MathElisha Angelyn Torres CastilloPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Differential EquationsDocument12 pagesDifferential EquationsaciddropsPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- 10 03 Elliptic PDEDocument41 pages10 03 Elliptic PDEJohn Bofarull GuixPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- Quadratic Equations-1Document53 pagesQuadratic Equations-1Thomas JonesPas encore d'évaluation

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- Euler's and Runge-Kutta Method PDFDocument8 pagesEuler's and Runge-Kutta Method PDFClearMind84Pas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- A First Course of Partial Differential Equations in Physical Sciences and Engineering PDEbook PDFDocument285 pagesA First Course of Partial Differential Equations in Physical Sciences and Engineering PDEbook PDFdomingocattoniPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- MAP 2302, Differential Equations ODE Test 1 Solutions Summer 09Document7 pagesMAP 2302, Differential Equations ODE Test 1 Solutions Summer 09alphacetaPas encore d'évaluation

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- De Notes Higher Order NonhomogeneousDocument9 pagesDe Notes Higher Order NonhomogeneousRichard Del RosarioPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Solving Sle by Graphing MethodDocument21 pagesSolving Sle by Graphing Methodapi-313517608Pas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (345)

- Logical FallaciesDocument14 pagesLogical FallaciesHAILE KEBEDE100% (1)

- Boundary Value Problems and Partial Differential Equations (Pdes)Document22 pagesBoundary Value Problems and Partial Differential Equations (Pdes)mziousPas encore d'évaluation

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- DM Lecture 3Document25 pagesDM Lecture 3Hassan SheraziPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 6 Wo QuizDocument29 pagesModule 6 Wo QuizVirgilio VelascoPas encore d'évaluation

- Laplace EquationDocument3 pagesLaplace EquationGaber GhaneemPas encore d'évaluation

- Eduction of PropositionDocument24 pagesEduction of PropositionFrancis De La CruzPas encore d'évaluation

- ExamDocument12 pagesExamAidar MukushevPas encore d'évaluation

- Model of A Heat Exchanger (Hyperbolic PDE)Document11 pagesModel of A Heat Exchanger (Hyperbolic PDE)Dionysios ZeliosPas encore d'évaluation

- Logic 9.10 12Document3 pagesLogic 9.10 12Jezen Esther PatiPas encore d'évaluation

- Engineering Mathematics 2 Jan 2014Document4 pagesEngineering Mathematics 2 Jan 2014Prasad C MPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Ch01 1Document146 pagesCh01 1suraj poudelPas encore d'évaluation

- Reasoning and Syllogism PHL 2 102 LogicDocument31 pagesReasoning and Syllogism PHL 2 102 Logicrufinus ondiekiPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus MAK501E - 2013 2014fall 1 PDFDocument2 pagesSyllabus MAK501E - 2013 2014fall 1 PDFkkaytugPas encore d'évaluation

- Dear Carnap, Dear Van (The Quine-Carnap Correspondence and Related Work)Document343 pagesDear Carnap, Dear Van (The Quine-Carnap Correspondence and Related Work)Alba Lissette Sánchez-MontenegroPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To ProofDocument17 pagesIntroduction To ProofAshish KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Rule Based Programming: 3rd Year, 2nd SemesterDocument17 pagesRule Based Programming: 3rd Year, 2nd SemesterDany DanielPas encore d'évaluation

- A Little Categorical/ Propositional Logic: Chapter 9 and 10Document33 pagesA Little Categorical/ Propositional Logic: Chapter 9 and 10Khánh Linh Lê0% (1)

- Solution of Differential EquationsDocument34 pagesSolution of Differential EquationsSaddie SoulaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reasoning Ability: Ibt Institute Pvt. LTDDocument9 pagesReasoning Ability: Ibt Institute Pvt. LTDANUP DUBEYPas encore d'évaluation

- Differential Equations Note Card.4Document2 pagesDifferential Equations Note Card.4Nicholas ManiaPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)