Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Dizziness

Transféré par

Vijay BabuTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Dizziness

Transféré par

Vijay BabuDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Inner Ear, Evaluation of Dizziness HISTORY

In the evaluation of a patient complaining of dizziness, the examiner's initial efforts must be directed at determining the exact nature of the patient's compla int because the pathophysiology determines the patient's sensations. Precisely u nderstanding the complaint determines the workup. For example, in a patient with syncope or presyncope, the cause of the sensation is probably cardiovascular an d not inner ear. In contrast, in a patient with a sensation of spinning or whirl ing, the pathology probably involves the inner ear or vestibular nerve on 1 side , though insults to the cerebellum and brainstem may also produce true vertigo. Therefore, the cause in a patient with true vertigo cannot be assumed to be peri pheral. Although close questioning and careful examination usually reveal important diff erences, conditions such as multiple sclerosis, migraine equivalent, and vertebr obasilar transient ischemic episodes may simulate peripheral vestibulopathy. Ver tigo, the hallmark of inner ear disease, is defined as the illusion of movement of either one's self or one's environment. An assessment of the patient's curren t history should address the following: Ask the patient to describe the symptoms without using the word dizzy. Have the patient differentiate vertigo from presyncope or near-syncope. Determine if the patient has a sense of being pushed down or pushed to 1 side (p ulsion). A peculiar sense of movement of objects viewed when the patient moves i s termed oscillopsia. Ascertain whether the symptoms are related to an anxiety episode; patients with agoraphobia may describe their symptoms as dizziness. Determine if the sensation is continuous or episodic; if episodic, find out if t he sensation is fleeting or prolonged. Ascertain whether the onset and progression of symptoms were slow and insidious or acute. Ask the patient about head trauma and other illnesses to determine the setting o f the initial symptoms. Trauma resulting in damage to an ear often manifests as unilateral hearing loss, which may be the cause of episodic vertigo even years l ater (posttraumatic hydrops). Determine if the episodes are associated with turning the head, lying supine, or sitting upright. Determine if symptoms of an upper respiratory infection or flu-like illness prec eded the onset of vertigo. Inquire about associated symptoms such as hearing loss or tinnitus (ringing in t he ears), aural fullness, diaphoresis, nausea, or emesis. Determine if the patient has an aura or warning before the symptoms start. If hearing loss is evident, find out if hearing fluctuates.

Determine if the patient has a headache or visual symptoms such as scintillating scotoma. Ask the patient about brainstem symptoms such as diplopia, dysarthria, facial pa resthesia, or extremity numbness or weakness. Ascertain the degree of impairment during an episode. Inquire about exposure to ototoxic medications, such as aminoglycosides and anti neoplastic drugs (especially cisplatin). These medications can damage vestibular hair cells and typically lead to progressive ataxia and/or oscillopsia. Because ototoxic medications simultaneously affect both labyrinths, they rarely cause v ertigo. When ototoxic patients describe vertigo, the condition almost always is related to head movement and is described as an uncomfortable sense of shifting or bobbing of viewed objects (oscillopsia). In obtaining the medical history, include the following: Determine if the patient has conditions such as diabetes (which can cause visual and proprioceptive problems), hypertension, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular d isease, migraine, or neurologic disease (eg, multiple sclerosis). Determine if the patient has any family history of cardiovascular disease, perip heral vascular disease, or migraine. Labyrinthine causes of vertigo usually are not inherited; however, rare exceptions (eg, Usher syndrome) are reported. Some clinical researchers believe that Mnire disease may have a hereditary predilection . Inquire about the patient's medications. The list of medications that can cause dizziness is long; the most common culprits are antihypertensive agents. Ask if the onset of the patient's symptoms was associated with starting a new medicatio n or a change in the dose or frequency of a medication. Determine if the patient has had ear surgery. Although surgery for chronic ear d isease only occasionally results in permanent vestibular injury, patients with a history of surgery for cholesteatoma may have an iatrogenic or acquired labyrin thine fistula. Patients who have undergone stapes surgery for otosclerosis or ty mpanosclerosis may develop vestibular symptoms because of perilymphatic fistula, adhesions between the oval window and saccule, or an overly long prosthesis. EXAMINATION OF ASSOCIATED SYSTEMS

Perform a complete examination of pertinent systems, such as the cardiovascular and neurologic systems (especially cranial nerves), before proceeding to specifi c office tests of the vestibular system. For example, if a patient complains of presyncope, perform auscultation of the heart and cervical vessels, and determin e orthostatic blood pressure and pulse. Examine the ears for a retracted or perf orated tympanic membrane or cholesteatoma. Assess hearing in both ears. OFFICE EXAMINATION OF THE VESTIBULAR SYSTEM

Balance involves the overlapping function of several systems, namely, the visual system, the proprioceptive system, and the vestibular system. Together, these s ystems maintain equilibrium. Although many of the office-based tests described b elow incorporate this triad of sensory systems, most tests concern the vestibula r system.

The primary goal of the vestibular system is to limit the slippage of images on the retina during head movement. Slippage of images greater than 2-3 per second b lurs visual acuity. The 3 systems that are involved in limiting retinal slip are (1) the smooth-pursuit system, (2) the optokinetic system (which work best at r elatively low head velocities), and (3) the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) system . In the VOR system, the semicircular canals are angular accelerometers, and the otolithic organs are linear accelerometers. Because most human movements are br isk (0.6-8.2 Hz, or <90 per second during walking to <170 per second during runnin g), the human vestibular system has evolved into a transducer of rapid head move ment, an observation that is reflected in many of the tests. For patients whose symptoms are episodic, physical examination findings may be n ormal between episodes. Furthermore, because the patient often can suppress nyst agmus caused by a peripheral vestibulopathy, many of the vestibulo-oculomotor te sts in the office examination are performed with +20 lenses (ie, cataract glasse s), which prevent the patient from focusing on objects in the visual surround.

SPECIFIC OFFICE TESTS OF BALANCE Gait test Determine whether the patient staggers or consistently leans to 1 side or the ot her. Oculomotor examination Assess for an internuclear ophthalmoplegia and gaze-dependent nystagmus. Nystagm us of peripheral (ie, labyrinthine) origin typically is unidirectional. Looking in the direction of the fast phase of nystagmus and preventing visual fixation w ith +20 lenses exaggerate the nystagmus. Nystagmus of brainstem or cerebellar (ie, central) origin may be bidirectional a nd have more than one direction, eg, torsional plus horizontal movement. Pure ve rtical nystagmus almost always is a sign of brainstem disease and not a labyrint hine disorder. Station (Romberg) The Romberg test originally was described as a test for tabes dorsalis. The shar pened Romberg test is having the patient stand heel to toe with 1 foot in front of the other; this test is required to detect abnormalities in younger patients. Fukuda test (stepping test of Unterberger) The patient is asked to step in place for 20-30 seconds. Rotation of the patient may indicate a unilateral loss of vestibular tone.

Dix-Hallpike maneuver The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is one of the most important tests for patients compla ining of true vertigo. This test involves having the patient lie back suddenly w ith the head turned to one side. The test results are considered abnormal if the patient reports vertigo and exhibits a characteristic torsional (ie, rotary) ny stagmus that starts a few seconds after the patient lies back (latency), lasts 4 0-60 seconds, reverses when the patient sits up, and fatigues with repetition (s ee Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo). Head-shake test The examiner vigorously shakes (approximately 1 Hz) the patient's head in the ho rizontal plane from side to side for 10-15 seconds. The patient is wearing +20 l enses to inhibit visual fixation. After the shaking is stopped, the eyes are obs erved for nystagmus. This test can reveal latent nystagmus and indicate which la byrinth is malfunctioning. By convention, the fast phase of nystagmus is the ter minology used to describe nystagmus. In this test, the fast phase of nystagmus i s directed toward the normal (or better-performing) labyrinth. Head-thrust test The patient is asked to gaze steadily at a target in the room. The examiner bris kly moves the patient's head from one side to the other while observing eye posi tion. A normal result is obtained when the patient's eyes remain fixed on the ta rget. When the eyes make a compensatory movement after the head is stopped to re acquire the target (a refixation saccade), the test results are abnormal. This t est can indicate if the output of one or both labyrinths is depressed. Oscillopsia test Before and during vigorous head shaking, the patient is asked to read the smalle st visible line on the Snellen eye chart. A normal result is the ability to main tain acuity within 2 lines of the acuity at rest. Oscillopsia is the result of b ilateral vestibulopathy, which most commonly is observed in ototoxicity. Fistula test The fistula test is designed to elicit symptoms and signs of an abnormal ion (fistula) between the labyrinth and surrounding spaces. Fistulas may ired, most commonly as a result of cholesteatoma or, less commonly, as a nce of bone overlying the superior semicircular canal. Iatrogenic causes chronic ear surgery and stapes surgery. connect be acqu dehisce include

The test involves the application of pressure to the patient's ear canal and obs ervation of eye movements with Frenzel lenses in place. Occluding the ear canal with the patient's tragus or using a Bruening otoscope can provide pressure to t he ear canal. The direction of nystagmus depends on the site of the fistula, a t opic that is beyond the scope of this article. Carefully examine the cranial nerves, especially cranial nerves V and VII. LABORATORY EXAMINATION OF THE VESTIBULAR SYSTEM

The following tests commonly are performed to evaluate patients with vertigo. Electronystagmography with caloric testing

This test has 2 parts, namely, oculomotor testing (pursuit and saccades) and cal oric testing. Eye position is monitored by using electro-oculography, which reli es on the dipole of the eye. In caloric testing, the ear canals are irrigated wi th water or air that is 7C above or below body temperature. The goal of the test is to determine if significant asymmetry is present in the response of the labyr inths, which can indicate peripheral vestibular disease. Evidence of CNS disorde rs also can be identified on electronystagmography. The caloric test may be helpful in determining the side of the lesion; however, it has several significant limitations. First, the test has a relatively poor re liability; test-retest values change markedly in the same patient. Second, the t est can be used to examine only a small portion of the balance system (ie, the l ateral canals) through a small range of frequencies. Hence, results of the test may not be generalized to the entire labyrinthine function of the tested subject . Rotational chair testing This test involves sinusoidally rotating the subject in a darkened booth while e ye position is monitored to assess the VOR. By comparing eye velocity to head ve locity (ie, velocity of the chair), one can determine VOR gain. The phase lead o f the response and any asymmetry in the response can also be determined. Vestibular autorotation testing Because rotational chair testing requires expensive and cumbersome equipment, th e vestibular autorotation test (VAT) has been developed to allow evaluation of t he VOR. Also, commercially available rotational chairs allow testing at only mod est head frequencies, typically less than 1 Hz, whereas VAT allows evaluation of the VOR at higher and more physiologically significant frequencies. The most co mmonly used system for VAT testing is from Western Systems Research, Inc. (Pasad ena, CA). The test is performed by using a computer-generated metronome to which the patie nt moves his or her head for an 18-second trial period at frequencies from 2-6 H z. Because high head frequencies are tested, smooth pursuit contributes little t o the response, and the test can be conducted in a lighted room while the patien t fixates on a stationary target. This test can evaluate both the vertical and h orizontal VOR. The best use of the test may be in monitoring the VOR stibulotoxic agents. The portability of the equipment hospitalized patients. The test/retest reliability of in the literature; therefore, it has not been adopted test of VOR function. Computerized platform posturography The tests described thus far address only 1 limb of the complex sensory and moto r interactions required to maintain balance. Because the maintenance of equilibr ium involves contributions from the vestibular system and the visual and somatos ensory systems, platform posturography was developed to assess equilibrium as a whole. The most commonly used system is the EquiTest. The patient stands on a platform, is secured in a harness, and faces a visual surround. Under the direction of th e computer, the platform and visual surround can move independently or together in response to patient sway. Force plates in the platform monitor the patient's sway and center of gravity. The computer records the information for analysis an d uses the information to move the surround during parts of the test. in patients who receive ve allows bedside testing of the test has been debated universally as a standard

The test protocol comprises 2 parts, namely, the motor-control test and the sens ory-organization test. In the motor-control test, the platform administers sudde n anteroposterior and posteroanterior translations while the force plates record the patient's response to the perturbations. Three movements (small, medium, an d large) are used to cause specified rotations around the ankle joint, shifting the center of gravity. In a different motor-control test, small toes-up and toes-down platform rotation s are presented. During both movements, the force plates record the distribution of weight over the feet during the movement, and the latency of the patient res ponse to platform movement is calculated. Conditions that disturb spinal reflexe s increase response latency during the motor control test. Adaptation to repeate d movements is also calculated. In the sensory-organization test, the platform and visual surround are manipulat ed to test the patient's relative reliance on VOR, visual, and proprioceptive/so matosensory systems. During the first 3 test conditions, the platform remains fi xed. In the first test condition, the subject stands quietly with eyes open whil e the platform and visual surround remain stationary. In the second test conditi on, the patient stands with eyes closed. In the third condition, the visual surr ound moves in response to information from the force plate, ie, when the patient leans forward, the visual surround falls away from the patient proportionally ( sway referencing). The effect of this condition is to remove reliable visual cue s, forcing the use of the vestibular system and, more importantly, the somatosen sory system. In test conditions 4, 5, and 6, the platform moves to follow the forward-backwar d sway of the patient. Platform movement removes reliable somatosensory cues for equilibrium. In condition 4, the visual surround remains fixed while the subjec t's eyes are open. In condition 5, the patient's eyes are closed. In condition 6 , both the platform and visual surround are sway referenced, providing inaccurat e visual and somatosensory information and forcing the reliance on vestibular in puts. The clinical usefulness of platform posturography continues to be debated. In ge neral, the consensus is that the test is not diagnostic for specific disease ent ities. The actual usefulness of the test is in the functional evaluation of equi librium in the following situations: Responses are documented in subjects with suspected malingering or psychiatric d isorders. The ability of platform posturography to detect malingerers by their s pecific patterns of response is well established. A program of vestibular rehabilitation is planned, and response to treatment is monitored in patients who have a variety of equilibrium problems. Patients who m ay be at particular risk of falling and sustaining possible injury can be monito red. Patients who have disequilibrium because of elevated cerebrospinal fluid pressur e can be monitored. Electrocochleography Although electrocochleography is not extremely sensitive, it is highly specific for conditions related to inner ear fluid imbalance (most commonly Mnire disease). Auditory brainstem response

Testing of the auditory brainstem response (ABR) can help in the diagnosis of ra re cases of microvascular compression of cranial nerve VIII in the cerebellopont ine angle or root-entry zone. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials A test of the patient's vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) can help d etermine the neural integrity of the saccule and inferior vestibular nerve. The saccule, which has some sound sensitivity, is innervated by means of the inferio r vestibular nerve. The inferior vestibular nerve has its main input to the late ral vestibular nucleus (Deiter nucleus), where the 2 main postural tracts origin ate. The medial vestibulospinal tract is responsible for postural control of the neck, whereas the lateral vestibulospinal tract is dedicated to the lower trunk and limbs. For the most part, sound-evoked VEMPs are considered completely unil ateral. The test is performed simply by placing EMG electrodes on the anterior neck musc les including the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The patient holds their head up un supported, using only their anterior neck muscles. The patient is instructed to tense the muscle during acoustic stimulation, and relax after the stimulation st ops. Loud clicks or tone bursts (95-100 DB nHL) are repetitively presented to ea ch ear. If the neck muscles are not activated, no VEMP is produced. This technology is currently still evolving, and its clinical utility is still b eing determined. The technology is currently being applied to patients with susp ected Mnire disease when the diagnosis is unclear. More recently, it has been appl ied to patients with superior canal dehiscence and vestibular schwannomas. PATH OLOGY AND TREATMENT Section 7 of 10 Author Information History Examination Of Associated Systems Office Examination Of The Vestibular System Specific Office Tests Of Balance Laboratory Examination Of The Vestibular System Pathology And Treatment Patient Education Pictures Bib liography

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo The most common cause of true vertigo is Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (B PPV). The classic history of an individual presenting with BPPV consists of comp laints of acute vertigo lasting less than 1 minute that occurs when the patient lies supine, sits up, rolls over in bed, or tilts his or her head backward. Afte r the patient assumes one of these positions, vertigo and torsional nystagmus us ually begin within 1-4 seconds. This latency period also applies to a reversal o f nystagmus when the patient returns to the upright position. BPPV is often related to head trauma; however, it is frequently is found in olde r patients without a clear history of head trauma. Particles (probably dislodged otoconia) that become trapped in the posterior semicircular canal cause BPPV. A lthough the posterior semicircular canal is the most common site of the lesion, in rare cases patients have horizontal or superior canal variants. Although the condition may spontaneously resolve in many patients, others seek m edical care for this unsettling problem. Medications, such as meclizine or benzo diazepines, are usually not helpful in the treatment of BPPV. The most effective treatment is repositioning of the canalith, which is an office-based maneuver i n which the particles are shifted out of the semicircular canal and into the ves tibule, where they do not cause symptoms. Vestibular neuritis

Intense vertigo that often begins acutely after an upper respiratory or flulike illness characterizes vestibular neuritis. Hearing is usually not affected. Seve re vertigo lasts 24-48 hours and gradually subsides. After the vertigo resolves, patients may complain of unsteadiness for weeks as t he vestibular system gradually accommodates. Treatment is usually symptomatic af ter one ensures that the patient does not have a central etiology of symptoms, s uch as Wallenberg syndrome. Drugs such as meclizine, promethazine, or prochlorpe razine are useful in suppressing vertigo and nausea and vomiting, which can be d istressing. Mnire disease Mnire disease (or syndrome) typically manifests as a combination of 4 symptoms, na mely, hearing that fluctuates in 1 ear (though Mnire disease can be bilateral), ti nnitus that fluctuates in 1 ear, aural fullness, and episodes of vertigo that la st for hours. However, Mnire disease often presents with just 1 or 2 symptoms of t he tetrad that occur months to years before involving the entire tetrad. Low-fre quency hearing loss is a typical manifestation in Mnire disease. A relative overproduction or underabsorption of endolymph is thought to cause Mnir e disease. The underlying etiology is unknown. Evaluate patients with suspected Mnire disease for syphilis, because patients who have late tertiary syphilis can p resent with identical symptoms. A fluorescein treponema antibody (FTA) test can be used for this purpose. Mnire disease initially is treated with sodium restriction and possibly diuresis. Vestibular suppressants are useful during episodes. A combination of a diuretic and a vestibular suppressant controls episodes of vertigo in 60-80% of patients. Patients whose symptoms fail to respond to conservative treatment and who conti nue to have episodes of vertigo may benefit from a variety of treatments. Transtympanic gentamicin can be used to perform a chemical labyrinthectomy to ex ploit the ototoxicity of this aminoglycoside. Endolymphatic sac decompression (ESD) can be performed. This outpatient procedur e is the most commonly performed surgery for Mnire disease. Through the mastoid, t he endolymphatic sac is exposed and freed of surrounding bone. Some surgeons ins ert a shunt to drain endolymph from the sac, though the benefit of this maneuver compared with simple decompression of the sac is not clear. With ESD, the rate of substantial control of symptoms is approximately 80% while it spares the pati ent's hearing. Sectioning of the vestibular nerve. This procedure is performed through a poster ior or middle fossa craniotomy. The vestibular division of cranial nerve VIII is cut, sparing the auditory division. The benefit of the operation is preservatio n of hearing in all but a few patients, with a >90% success rate in terminating episodes of vertigo. Labyrinthectomy can be performed in patients with unilateral symptoms who have p oor hearing that cannot be improved by a hearing aid. This procedure remains the criterion standard in the treatment of unilateral Mnire disease and the highest s uccess rate in terminating episodes of vertigo. However, all of the remaining he aring in the treated ear is lost. Superior canal dehiscence Superior canal dehiscence syndrome is a recently described entity in which the s uperior semicircular canal has become dehiscent in the floor of the middle fossa

. Patients tend to report that loud sounds or pressure changes exacerbate their vertiginous symptoms. The diagnosis is typically made with a high-resolution com puted tomography scan. Surgical treatment currently involves a middle fossa cran iectomy with diagnosis and patching of the dehiscent canal. Central causes Exclude central causes in patients with vertigo. Etiologies such as multiple scl erosis (see Image 1), Wallenberg lateral medullary syndrome, cerebellar ischemia or infarction (see Image 2), benign or malignant CNS or posterior fossa neoplas ms (see Image 3), or Arnold-Chiari malformation (see Image 4) may cause patients to present with vertigo and signs of vestibular disturbance. In almost every ca se, careful neurologic examination and examination of the peripheral vestibular system reveal either CNS abnormalities or other cranial nerve abnormalities

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5794)

- Benign Positional Vertigo: Taleb Mohammed Mansoor Khaleil Ebrahem Al-MatroushiDocument27 pagesBenign Positional Vertigo: Taleb Mohammed Mansoor Khaleil Ebrahem Al-MatroushiSheila CantikPas encore d'évaluation

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (400)

- Epley Manoeuvre Quick GuideDocument10 pagesEpley Manoeuvre Quick GuideVijay BabuPas encore d'évaluation

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- Eustachian TubeDocument6 pagesEustachian TubeMusyfiqoh TusholehahPas encore d'évaluation

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (895)

- Throat Pharynx (Premalignant and Malignant)Document78 pagesThroat Pharynx (Premalignant and Malignant)Vannero SembranoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Facial Nerve AnatomyDocument9 pagesFacial Nerve AnatomyVijay BabuPas encore d'évaluation

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- ENT QuestionsDocument24 pagesENT QuestionsVijay BabuPas encore d'évaluation

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- Multiple Cranial Nerve PalsiesDocument11 pagesMultiple Cranial Nerve PalsiesVijay BabuPas encore d'évaluation

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- A Tool For The Assessment of Project Com PDFDocument9 pagesA Tool For The Assessment of Project Com PDFgskodikara2000Pas encore d'évaluation

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (588)

- (Durt, - Christoph - Fuchs, - Thomas - Tewes, - Christian) Embodiment, Enaction, and Culture PDFDocument451 pages(Durt, - Christoph - Fuchs, - Thomas - Tewes, - Christian) Embodiment, Enaction, and Culture PDFnlf2205100% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (74)

- RPT Form 2 2023Document7 pagesRPT Form 2 2023NOREEN BINTI DOASA KPM-GuruPas encore d'évaluation

- Humanistic Developmental Physiological RationalDocument10 pagesHumanistic Developmental Physiological RationalJin TippittPas encore d'évaluation

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- Financial Crisis Among UTHM StudentsDocument7 pagesFinancial Crisis Among UTHM StudentsPravin PeriasamyPas encore d'évaluation

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (266)

- Units 6-10 Review TestDocument20 pagesUnits 6-10 Review TestCristian Patricio Torres Rojas86% (14)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- Schiffman Cb09 PPT 06Document49 pagesSchiffman Cb09 PPT 06Parth AroraPas encore d'évaluation

- Public BudgetingDocument15 pagesPublic BudgetingTom Wan Der100% (4)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Marketing Plan For Paraiso Islet ResortDocument25 pagesMarketing Plan For Paraiso Islet ResortEllaine Claire Lor100% (1)

- Bug Tracking System AbstractDocument3 pagesBug Tracking System AbstractTelika Ramu86% (7)

- TOEIC® Practice OnlineDocument8 pagesTOEIC® Practice OnlineCarlos Luis GonzalezPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2259)

- A100K10873 VSP-12-Way Technical ManualDocument20 pagesA100K10873 VSP-12-Way Technical Manualchufta50% (2)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- Ccounting Basics and Interview Questions AnswersDocument18 pagesCcounting Basics and Interview Questions AnswersAamir100% (1)

- Donna Claire B. Cañeza: Central Bicol State University of AgricultureDocument8 pagesDonna Claire B. Cañeza: Central Bicol State University of AgricultureDanavie AbergosPas encore d'évaluation

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- CV AmosDocument4 pagesCV Amoscharity busoloPas encore d'évaluation

- Individual Psychology (Adler)Document7 pagesIndividual Psychology (Adler)manilyn dacoPas encore d'évaluation

- Context: Lesson Author Date of DemonstrationDocument4 pagesContext: Lesson Author Date of DemonstrationAR ManPas encore d'évaluation

- Practice Makes Perfect Basic Spanish Premium Third Edition Dorothy Richmond All ChapterDocument67 pagesPractice Makes Perfect Basic Spanish Premium Third Edition Dorothy Richmond All Chaptereric.temple792100% (3)

- Lecture 6Document7 pagesLecture 6Shuja MirPas encore d'évaluation

- SAP CRM Tax ConfigurationDocument18 pagesSAP CRM Tax Configurationtushar_kansaraPas encore d'évaluation

- Eugène Burnouf: Legends of Indian Buddhism (1911)Document136 pagesEugène Burnouf: Legends of Indian Buddhism (1911)Levente Bakos100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (121)

- Confidential Recommendation Letter SampleDocument1 pageConfidential Recommendation Letter SamplearcanerkPas encore d'évaluation

- 3er Grado - DMPA 05 - ACTIVIDAD DE COMPRENSION LECTORA - UNIT 2 - CORRECCIONDocument11 pages3er Grado - DMPA 05 - ACTIVIDAD DE COMPRENSION LECTORA - UNIT 2 - CORRECCIONANDERSON BRUCE MATIAS DE LA SOTAPas encore d'évaluation

- Tamil Ilakkanam Books For TNPSCDocument113 pagesTamil Ilakkanam Books For TNPSCkk_kamalakkannan100% (1)

- Debus Medical RenaissanceDocument3 pagesDebus Medical RenaissanceMarijaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2022BusinessManagement ReportDocument17 pages2022BusinessManagement ReportkianaPas encore d'évaluation

- Pace, ART 102, Week 6, Etruscan, Roman Arch. & SculpDocument36 pagesPace, ART 102, Week 6, Etruscan, Roman Arch. & SculpJason ByrdPas encore d'évaluation

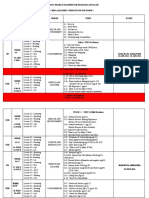

- Nin/Pmjay Id Name of The Vaccination Site Category Type District BlockDocument2 pagesNin/Pmjay Id Name of The Vaccination Site Category Type District BlockNikunja PadhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Amor Vs FlorentinoDocument17 pagesAmor Vs FlorentinoJessica BernardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Electronic Load FundamentalsDocument16 pagesElectronic Load FundamentalsMiguel PenarandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)