Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Fernando Santos Vs Spouses Reyes

Transféré par

Buenavista Mae BautistaTitre original

Copyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Fernando Santos Vs Spouses Reyes

Transféré par

Buenavista Mae BautistaDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

1.

Fernando Santos vs Spouses Reyes FACTS: In June 1986, Fernando Santos (70%), Nieves Reyes (15%), and Melton Zabat (15%) orally instituted a partnership with them as partners. Their venture is to set up a lending business where it was agreed that Santos shall be financier and that Nieves and Zabat shall contribute their industry. **The percentages after their names denote their share in the profit. Later, Nieves introduced Cesar Gragera to Santos. Gragera was the chairman of a corporation. It was agreed that the artnership shall provide loans to the employees of Grageras corporation and Gragera shall earn commission from loan payments. In August 1986, the three partners put into writing their verbal agreement to form the partnership. As earlier agreed, Santos shall finance and Nieves shall do the daily cash flow more particularly from their dealings with Gragera, Zabat on the other hand shall be a loan investigator. But then later, Nieves and Santos found out that Zabat was engaged in another lending business which competes with their partnership hence Zabat was expelled. The two continued with the partnership and they took with them Nieves husband, Arsenio, who became their loan investigator. Later, Santos accused the spouses of not remitting Grageras commissions to the latter. He sued them for collection of sum of money. The spouses countered that Santos merely filed the complaint because he did not want the spouses to get their shares in the profits. Santos argued that the spouses, insofar as the dealing with Gragera is concerned, are merely his employees. Santos alleged that there is a distinct partnership between him and Gragera which is separate from the partnership formed between him, Zabat and Nieves. The trial court as well as the Court of Appeals ruled against Santos and ordered the latter to pay the shares of the spouses. ISSUE: Whether or not the spouses are partners. HELD: Yes. Though it is true that the original partnership between Zabat, Santos and Nieves was terminated when Zabat was expelled, the said partnership was however considered continued when Nieves and Santos continued engaging as usual in the lending business even getting Nieves husband, who resigned from the Asian Development Bank, to be their loan investigator who, in effect, substituted Zabat. There is no separate partnership between Santos and Gragera. The latter being merely a commission agent of the partnership. This is even though the partnership was formalized shortly after Gragera met with Santos (Note that Nieves was even the one who introduced Gragera to Santos exactly for the purpose of setting up a lending agreement between the corporation and the partnership). HOWEVER, the order of the Court of Appeals directing Santos to give the spouses their shares in the profit is premature. The accounting made by the trial court is based on the total income of the partnership. Such total income calculated by the trial court did not consider the expenses sustained by the partnership. All expenses incurred by the money-lending enterprise of the parties must first be deducted from the total income in order to arrive at the net profit of the partnership. The share of each one of them should be based on this net profit and not from the gross income or total income.

A contract by and between Noguera and Tourist World Service (TWS), represented by Canilao, wherein TWS leased the premises belonging to Noguera as branch office of TWS. When the branch office was opened, it was run by appellant Sevilla payable to TWS by any airline for any fare brought in on the efforts of Mrs. Sevilla, 4% was to go to Sevilla and 3% was to be withheld by the TWS. Later, TWS was informed that Sevilla was connected with rival firm, and since the branch office was losing, TWS considered closing down its office. On January 3, 1962, the contract with appellee for the use of the branch office premises was terminated and while the effectivity thereof was January 31, 1962, the appellees no longer used it. Because of this, Canilao, the secretary of TWS, went over to the branch office, and finding the premises locked, he padlocked the premises. When neither appellant Sevilla nor any of his employees could enter, a complaint was filed by the appellants against the appellees. TWS insisted that Sevilla was a mere employee, being the branch manager of its branch office and that she had no say on the lease executed with the private respondent, Noguera. ISSUE: W/N ER-EE relationship exists between Sevilla and TWS HELD: The records show that petitioner, Sevilla, was not subject to control by the private respondent TWS. In the first place, under the contract of lease, she had bound herself in solidum as and for rental payments, an arrangement that would belie claims of a master-servant relationship. That does not make her an employee of TWS, since a true employee cannot be made to part with his own money in pursuance of his employers business, or otherwise, assume any liability thereof. In the second place, when the branch office was opened, the same was run by the appellant Sevilla payable to TWS by any airline for any fare brought in on the effort of Sevilla. Thus, it cannot be said that Sevilla was under the control of TWS. Sevilla in pursuing the business, relied on her own capabilities. It is further admitted that Sevilla was not in the companys payroll. For her efforts, she retained 4% in commissions from airline bookings, the remaining 3% going to TWS. Unlike an employee, who earns a fixed salary, she earned compensation in fluctuating amount depending on her booking successes. The fact that Sevilla had been designated branch manager does not make her a TWS employee. It appears that Sevilla is a bona fide travel agent herself, and she acquired an interest in the business entrusted to her. She also had assumed personal obligation for the operation thereof, holding herself solidary liable for the payment of rentals. Wherefore, TWS and Canilao are jointly and severally liable to indemnify the petitioner, Sevilla. 3. ESTANISLAO, JR. VS. COURT OF APPEALS

2. FACTS:

Sevilla vs. CA

Facts: The petitioner and private respondents are brothers and sisters who are co-owners of certain lots at the in Quezon City which were then being leased to SHELL. They agreed to open and operate a gas station thereat to be known as Estanislao Shell Service Station with an initial investment of PhP15,000.00 to be taken from the advance rentals due to them from SHELL for the occupancy of the said lots owned in common by them. A joint affidavit was executed by them on April 11, 1966. The respondents agreed to help their brother, petitioner therein, by allowing him to operate and manage the gasoline service station of the family. In order not to run counter to the companys policy of appointing only one dealer, it

was agreed that petitioner would apply for the dealership. Respondent Remedios helped in co-managing the business with petitioner from May 1966 up to February 1967. On May 1966, the parties entered into an Additional Cash Pledge Agreement with SHELL wherein it was reiterated that the P15,000.00 advance rental shall be deposited with SHELL to cover advances of fuel to petitioner as dealer with a proviso that said agreement cancels and supersedes the Joint Affidavit. For sometime, the petitioner submitted financial statement regarding the operation of the business to the private respondents, but thereafter petitioner failed to render subsequent accounting. Hence , the private respondents filed a complaint against the petitioner praying among others that the latter be ordered: (1) To execute a public document embodying all the provisions of the partnership agreement they entered into; (2) To render a formal accounting of the business operation veering the period from May 6, 1966 up to December 21, 1968, and from January 1, 1969 up to the time the order is issued and that the same be subject to proper audit; (3) To pay the plaintiffs their lawful shares and participation in the net profits of the business; and (4) To pay the plaintiffs attorneys fees and costs of the suit. Issue: Can a partnership exist between members of the same family arising from their joint ownership of certain properties? Trial Court: The complaint (of the respondents) was dismissed. But upon a motion for reconsideration of the decision, another decision was rendered in favor of the respondents. CA: Affirmed in toto Petitioner: The CA erred in interpreting the legal import of the Joint Affidavit vis--vis the Additional Cash Pledge Agreement. Because of the stipulation cancelling and superseding the Joint Affidavit, whatever partnership agreement there was in said previous agreement had thereby been abrogated. Also, the CA erred in declaring that a partnership was established by and among the petitioner and the private respondents as regards the ownership and /or operation of the gasoline service station business. Held: There is no merit in the petitioners contention that because of the stipulation cancelling and superseding the previous joint affidavit, whatever partnership agreement there was in said previous agreement had thereby been abrogated. Said cancelling provision was necessary for the Joint Affidavit speaks of P15,000.00 advance rental starting May 25, 1966 while the latter agreement also refers to advance rentals of the same amount starting May 24, 1966. There is therefore a duplication of reference to the P15,000.00 hence the need to provide in the subsequent document that it cancels and supercedes the previous none. Indeed, it is true that the latter document is silent as to the statement in the Join Affidavit that the value represents the capital investment of the parties in the business and it speaks of the petitioner as the sole dealer, but this is as it should be for in the latter document, SHELL was a signatory and it would be against their policy if in the agreement it should be stated that the business is a partnership with private respondents and not a sole proprietorship of the petitioner. Furthermore, there are other evidences in the record which show that there was in fact such partnership agreement between parties. The petitioner submitted to the private respondents periodic accounting of the business and gave a written authority to the private respondent Remedios Estanislao to examine and audit the books of their common business (aming negosyo). The respondent Remedios, on the other hand, assisted in the running of

the business. Indeed, the parties hereto formed a partnership when they bound themselves to contribute money in a common fund with the intention of dividing the profits among themselves.

4.

Feu Leung vs Intermediate Appellate Court

Facts:The Sun WahPanciteria, a restaurant, located at Florentino Torres Street, Sta. Cruz, Manila, wasestablished sometime in October, 1955. It was registered as a single proprietorship and its licenses andpermits were issued to and in favor of petitioner Dan Fue Leung as the sole proprietor. RespondentLeung Yiu adduced evidence during the trial of the case to show that Sun WahPanciteria was actually apartnership and that he was one of the partners having contributed P4,000.00 to its initialestablishment. Issue:whether or not the private respondent is a partner of the petitioner in the establishmentofSunWahPanciteria. Held: private respondent is a partner of the petitioner in Sun more persons bind themselves to contribute money, property, or industry to acommon fund; and 2) intention on the part of the partners to divide the profits among themselves havebeen established. As stated by the respondent, a partner shares not only in profits but also in the lossesof the firm. If excellent relations exist among the partners at the start of business and all the partnersare more interested in seeing the firm grow rather than get immediate returns, a deferment of sharingin the profits is perfectly plausible. It would be incorrect to state that if a partner does not assert hisrights anytime within ten years from the start of operations, such rights are irretrievably lost. Theprivate respondent's cause of action is premised upon the failure of the petitioner to give him theagreed profits in the operation of Sun WahPanciteria. In effect the private respondent was asking for anaccounting of his interests in the partnership

5.

Fernando Santos vs Spouses Reyes

6.

Lilibeth Sunga-Chan vs Lamberto Chua

FACTS: In 1977, Chua and Jacinto Sunga verbally agreed to form a partnership for the sale and distribution of Shellane LPGs. Their business was very profitable but in 1989 Jacinto died. Upon Jacintos death, his daughter Lilibeth took over the business as well as the business assets. Chua then demanded for an accounting but Lilibeth kept on evading him. In 1992 however, Lilibeth gave Chua P200k. She said that the same represents a partial payment; that the rest will come after she finally made an accounting. She never made an accounting so in 1992, Chua filed a complaint for Winding Up of Partnership Affairs, Accounting, Appraisal and Recovery of Shares and Damages with Writ of Preliminary Attachment against Lilibeth. Lilibeth in her defense argued among others that Chuas action has prescribed. ISSUE: Whether or not Chuas claim is barred by prescription. HELD: No. The action for accounting filed by Chua three (3) years after Jacintos death was well within the prescribed period. The Civil Code provides that an action to enforce an oral contract prescribes in six (6) years while the right to demand an accounting

for a partners interest as against the person continuing the business accrues at the date of dissolution, in the absence of any contrary agreement. Considering that the death of a partner results in the dissolution of the partnership, in this case, it was after Jacintos death that Chua as the surviving partner had the right to an account of his interest as against Lilibeth. It bears stressing that while Jacintos death dissolved the partnership, the dissolution did not immediately terminate the partnership. The Civil Code expressly provides that upon dissolution, the partnership continues and its legal personality is retained until the complete winding up of its business, culminating in its termination.

June 20, 1958: SJP amended Statement increasing 2,000,000 to 5,000,000, at a reduced offering price of from P1.00 to P0.70 per share Pedro R. Palting together with other investors in the share of SJP filed with the SEC an opposing the registration and licensing of the securities on the grounds that: tie-up between the issuer, SJP, a Panamanian corp. and San Jose Oil (SJO), a domestic corporation, violates the Constitution of the Philippines, the Corporation Law and the Petroleum Act of 1949 issuer has not been licensed to transact business in the Philippines sale of the shares of the issuer is fraudulent, and works or tends to work a fraud upon Philippine purchasers issuer as an enterprise, as well as its business, is based upon unsound business principles

1.

2. 7. Pedro Palting vs San Jose Petroleum, Inc. In 1956, San Jose Petroleum, Inc. (SJP), a mining corporation organized under the laws of Panama, was allowed by the Securitiesand Exchange Commission (SEC) to sell its shares of stocks in the Philippines. Apparently, the proceeds of such sale shall beinvested in San Jose Oil Company, Inc. (SJO), a domestic mining corporation. Pedro Palting opposed the authorization granted to SJP because said tie up between SJP and SJO is violative of the constitution; that SJO is 90% owned by SJP; that the other 10% is owned by another foreign corporation; that a mining corporation cannot be interested in another mining corporation. SJP on the other hand invoked that under the parity rights agreement (LaurelLangley Agreement), SJP, a foreign corporation, is allowed toinvest in a domestic corporation. ISSUE: Whether or not SJP is correct. HELD: No. The parity rights agreement is not applicable to SJP. The parity rights are only granted to American business enterprises or enterprises directly or indirectly controlled by US citizens. SJP is a Panamanian corporate citizen. The other owners of SJO are Venezuelan corporations, not Americans. SJP was not able to show contrary evidence. Further, the Supreme Courtemphasized that the stocks of these corporations are being traded in stocks exchanges abroad which renders their foreign ownership subject to change from time to time. This fact renders a practical impossibility to meet the requirements under the parity rights. Hence, the tie up between SJP and SJO is illegal, SJP not being a domestic corporation or an American businessenterprise contemplated under the LaurelLangley Agreement Palting v. San Jose Petroleum G.R. No. L-14441 December 17, 1966 FACTS: September 7, 1956: San Jose Petroleum (SJP) filed with the Philippine Securities and Exchange Commission a sworn registration statement, for the registration and licensing for sale in the Philippines Voting Trust Certificates representing 2,000,000 shares of its capital stock of a par value of $0.35 a share, at P1.00 per share 3. 4.

ISSUES: 1. 2. W/N Pedro R. Palting, as a "prospective investor" in SJP's securities, has personality to file -YES W/N the tie-up violates the Constitution of the Philippines, the Corporation Law and the Petroleum Act of 1949 (Up to what level do you apply the grandfather rule?) - YES

HELD: motion of respondent to dismiss this appeal, is denied and the orders of the Securities and Exchange Commissioner, allowing the registration of Respondent's securities and licensing their sale in the Philippines are hereby set aside. The case is remanded to the Securities and Exchange Commission for appropriate action in consonance with this decision. 1. YES any person (who may not be "aggrieved" or "interested" within the legal acceptation of the word) is allowed or permitted to file an opposition to the registration of securities for sale in the Philippines eliminating the word "aggrieved" appearing in the old Rule, being procedural in nature, and in view of the express provision of Rule 144 that the new rules made effective on January 1, 1964 shall govern not only cases brought after they took effect but all further proceedings in cases then pending, except to the extent that in the opinion of the Court their application would not be feasible or would work injustice, in which event the former procedure shall apply

*amiscus curae -stranger to the case 2. YES

It was alleged that the entire proceeds of the sale of said securities will be devoted or used exclusively to finance the operations of San Jose Oil Company, Inc. (Domestic Mining Oil Company) express condition of the sale that every purchaser of the securities shall not receive a stock certificate, but a registered or bearervoting-trust certificate from the voting trustees James L. Buckley and Austin G.E. Taylor

SJO (domestic)- 90% owned by SJP (foreign) wholly owned by Pantepec Oil Co. and Pancoastel Petroleum, both organized and existing under the laws of Venezuela CANNOT go beyond the level of what is reasonable SJO is not a party and it is not necessary to do so to dispose of the present controversy. SJP actually lost $4,550,000.00, which was received by SJO Articles of Incorporation of SJP is unlawful:

1. 2.

3.

the directors of the Company need not be shareholders; that in the meetings of the board of directors, any director may be represented and may vote through a proxy who also need not be a director or stockholder; and that no contract or transaction between the corporation and any other association or partnership will be affected, except in case of fraud, by the fact that any of the directors or officers of the corporation is interested in, or is a director or officer of, such other association or partnership, and that no such contract or transaction of the corporation with any other person or persons, firm, association or partnership shall be affected by the fact that any director or officer of the corporation is a party to or has an interest in, such contract or transaction, or has in anyway connected with such other person or persons, firm, association or partnership; and finally, that all and any of the persons who may become director or officer of the corporation shall be relieved from all responsibility for which they may otherwise be liable by reason of any contract entered into with the corporation, whether it be for his benefit or for the benefit of any other person, firm, association or partnership in which he may be interested.

industry, or any of these things, in order to obtain profit, shall be commercial, no matter what it class may be, provided it has been established in accordance with the provisions of the Code. However in this case, there was no common fund. The business belonged to Menzi & Co. The plaintiff was working for Menzi, and instead of receiving a fixed salary, he was to receive 35% of the net profits as compensation for his services. The phrase in the written contract en sociedad con, which is used as a basis of the plaintiff to prove partnership in this case, merely means en reunion con or in association with. It is also important to note that although Menzi agreed to furnish the necessary financial aid for the fertilizer business, it did not obligate itself to contribute any fixed sum as capital or to defray at its own expense the cost of securing the necessary credit. 9. Magalona vs Pesayco 10. Agad vs Mabato Facts: Petitioner Mauricio Agad claims that he and defendant Severino Mabato are partners in a fishpond business to which they contributed P1000 each. As managing partner, Mabato yearly rendered the accounts of the operations of the partnership. However, for the years 1957-1963, defendant failed to render the accounts despite repeated demands. Petitioner filed a complaint against Mabato to which a copy of the public instrument evidencing their partnership is attached. Aside from the share of profits (P14,000) and attorneys fees (P1000), petitioner prayed for the dissolution of the partnership and winding up of its affairs. Mabato denied the existence of the partnership alleging that Agad failed to pay hisP1000 contribution. He then filed a motion to dismiss on the ground of lack of cause of action. The lower court dismissed the complaint finding a failure to state a cause of action predicated upon the theory that the contract of partnership is null and void, pursuant to Art. 1773 of our Civil Code, because an inventory of the fishpond referred in said instrument had not been attached thereto. Art. 1771. A partnership may be constituted in any form, except where immovable property or real rights are contributed thereto, in which case a public instrument shall be necessary. Art. 1773. A contract of partnership is void, whenever immovable property is contributed thereto, if inventory of said property is not made, signed by the parties; and attached to the public instrument. Issue: Whether or not immovable property or real rights have been contributed to the partnership. Held: Based on the copy of the public instrument attached in the complaint, the partnership was established to operate a fishpond", and not to "engage in a fishpond business. Thus, Mabatos contention that it is really inconceivable how a partnership engaged in the fishpond business could exist without said fishpond property (being) contributed to the partnership is without merit. Their contributions were limited to P1000 each and neither a fishpond nor a real right thereto was contributed to the partnership. Therefore, Article 1773 of the Civil Code finds no application in the case at bar. Case remanded to the lower court for further proceedings.

8.

Bastida vs Menzi

Facts: Bastida offered to assign to Menzi & Co. his contract with Phil Sugar Centrals Agency and to supervise the mixing of the fertilizer and to obtain other orders for 50 % of the net profit that Menzi & Co., Inc., might derive therefrom. J. M. Menzi (gen. manager of Menzi & Co.) accepted the offer. The agreement between the parties was verbal and was confirmed by the letter of Menzi to the plaintiff on January 10, 1922. Pursuant to the verbal agreement, the defendant corporation on April 27, 1922 entered into a written contract with the plaintiff, marked Exhibit A, which is the basis of the present action. Still, the fertilizer business as carried on in the same manner as it was prior to the written contract, but the net profit that the plaintiff herein shall get would only be 35%. The intervention of the plaintiff was limited to supervising the mixing of the fertilizers in the bodegas of Menzi. Prior to the expiration of the contract (April 27, 1927), the manager of Menzi notified the plaintiff that the contract for his services would not be renewed. Subsequently, when the contract expired, Menzi proceeded to liquidate the fertilizer business in question. The plaintiff refused to agree to this. It argued, among others, that the written contract entered into by the parties is a contract of general regular commercial partnership, wherein Menzi was the capitalist and the plaintiff the industrial partner. Issue: Is the relationship between the petitioner and Menzi that of partners? Held: The relationship established between the parties was not that of partners, but that of employer and employee, whereby the plaintiff was to receive 35% of the net profits of the fertilizer business of Menzi in compensation for his services for supervising the mixing of the fertilizers. Neither the provisions of the contract nor the conduct of the parties prior or subsequent to its execution justified the finding that it was a contract of copartnership. The written contract was, in fact, a continuation of the verbal agreement between the parties, whereby the plaintiff worked for the defendant corporation for onehalf of the net profits derived by the corporation form certain fertilizer contracts. According to Art. 116 of the Code of Commerce, articles of association by which two or more persons obligate themselves to place in a common fund any property,

11. THE GREAT COUNCIL OF THE UNITED STATES OF THE IMPROVED ORDER OF RED MEN, plaintiff-appellee, vs. THE VETERAN ARMY OF THE PHILIPPINES, defendant-appellant. FACTS: Defendant as represented by Albert McCabe entered into a

contract of lease with the plaintiff. Plaintiff and defendant being the lessor and lessee respectively. An action was commenced by the plaintiff against defendant to recover the rent for the unexpired lease term. Judgment was rendered against defendant.From this judgment, the last named defendant has appealed. The plaintiff did not appeal from the judgment acquitting defendant McCabe of the complaint. It is claimed by the appellant that the action can not be maintained by the plaintiff, The Great Council of the United States of the Improved Order of Red Men, as this organization did not make the contract of lease. It is also claimed that the action can not be maintained against the Veteran Army of the Philippines because it never contradicted, either with the plaintiff or with Apach Tribe, No. 1, and never authorized anyone to so contract in its name. ISSUE: WON defendant is a partnership thus making it liable for the unexpired lease term in the contract. RULING: SC held that no contract, such as the one in question, is binding on the Veteran Army of the Philippines unless it was authorized at a meeting of the department. No evidence was offered to show that the department had never taken any such action. In fact, the proof shows that the transaction in question was entirely between Apache Tribe, No. 1, and the Lawton Post, and there is nothing to show that any member of the department ever knew anything about it, or had anything to do with it. The liability of the Lawton Post is not presented in this appeal. The society (Veteran Army) was not constituted for the purpose of gain. it does not fall within this article of the Civil Code. Such an organization is fully covered by the Law of Associations of 1887, but that law was never extended to the Philippine Islands. According to some commentators it would be governed by the provisions relating to the community of property. However, the questions thus presented we do not find necessary to , and to not resolve. The view most favorable to the appellee is the one that makes the appellant a civil partnership. Assuming that is such, and is covered by the provisions of title 8, book 4 of the Civil Code, it is necessary for the appellee to prove that the contract in question was executed by some authorized to so by the Veteran Army of the Philippines.Judgment against the appellant is reversed, and the Veteran Army of the Philippines is acquitted of the complaint. 12. Criado vs Gutierrez Hermanos FACTS: In January 1900, Placido Gutierrez de Celis (37%), Miguel Gutierrez de Celis (37%), Miguel Alfonso (16%), Daniel Perez (5%), and Leopoldo Criado (5%) formed a partnership called Gutierrez Hermanos. Perez and Criado were the industrialist partners while the other three are the capitalist partners. **The percentages after their names denote their share in the profit. In 1903, with the death of one partner (Alfonso), they agreed to liquidate the partnership. In the liquidation, it was put into record in the partnerships books that Criado only had a balance of P25,129.09. Criado immediately protested as he claimed that his balance in the partnership should be P55,738.69, but Miguel persuaded Criado not to protest anymore as he made assurances that the difference shall be paid later on by the new partnership that they will be forming. Miguel convinced Criado to make it appear that the partnership has incurred losses from 1900 to 1903 and that his share in the losses, based on Criados 5% share in profits is deducted from his actual P55k+ balance. Miguel said they have to do

this in order to avoid some creditor claims against them, among others. Incidentally, Alfonso also owe P1k from Criado but Miguel assured that the same shall be paid by the new partnership. So in 1904, a new partnership was formed involving the remaining 4 original partners. They still called themselves HermanosGuttierez. This time they are all capitalist partners and Criado contributed his P25,129.09 from the first phase of the partnership. The second phase of the partnership went on until such time that Criado got tired of it because Miguel never made good his word to reimburse him of his remaining balance from the first phase of the partnership. And so a liquidation was made and in December 1911, Criado left the firm. Miguel requested Criado to render service in lieu of theliquidation which Criado complied until the partnership was fully liquidated in March 1912. ISSUES: 1. Whether or not Criado is estopped from claiming his balance from the first phase of the partnership considering that he did sign the new partnership agreement which indicated that the remaining balance hes bringing in to the second phase from the first phase of the partnership was only P25k+. 2. Whether or not Criado is liable for losses. 3. Whether or not Criado should be compensated for his services in the liquidation. HELD: 1. No. There is no estoppel. It cannot be held that Criado was in estoppel immediately after having signed the partnership contract of 1904, in which it appears that he brought into the new firm, as capital of his own, P25,129.09, nor may it be said that he was not entitled to claim the rest of his assets in the firm during the first period from 1900 to 1903, to wit, his actual balance P55,738.69 less simulated balance in lieu of Miguels assurances of P25,129.09 = P30,609.60. Criado merely relied on the repeated promises of Miguel hence estoppel cannot be setup against him. 2. No. He is an industrialist partner. Hence, this reinforces number (1). 3. Yes. At the time of the last liquidation, Criado was not a managing partner. In the Code of Commerce, managing partners are the ones obliged to be in charge of the liquidation. Criado without being obliged took charge in the liquidation and this was even upon the request of Miguel himself hence, Criado is entitled to compensation (which as he claims is P1k per month). Gutierrez Hermanos Cross Claim The firm made a cross claim whereby it alleged that at one time when Criado was a managing partner, he delivered goods and provided loans to certain persons without any security for said goods and loans. And because of such, the firm incurred damage. The above claim by the firm against Criado is bereft of merit. According to the law, in order that the partner at fault may be compelled to pay an indemnity, it is indispensable, in the first, place, that his conduct shall have caused some damage to the partnership, and, in the second place, that his conduct should not have been expressly or impliedly ratified by the other partners or the manager of the partnership. Hermanos was not able to prove such damages by sufficient evidence. 13. Garrido vs Asencio 14. Dan Feu Leung vs IAC 15. Sharuff & Co. v. Baloise Fire Insurance Co. (1937)

FACTS: Salomon Sharruf and Elias Eskenazi were doing business under the firm name of Sharruf & Co. They insured their stocks with aloise Fire Insurance Co., Sun Insurance Office Ltd., and Springfield Insurance Co. raising it to P40,000. Elias Eskenazi having paid the corresponding premiums. Soon they changed the name of their partnership to Sharruf & Eskenazi September 22, 1933: A fire ensued at their building at Muelle de la Industria street where petroleum was spilt lasting 27 minutes Sharruf & Co. claimed 40 cases when only 10 or 11 partly burned and scorched cases were found RTC: ordered Baloise Fire Insurance Co., Sun Insurance Office Ltd., and Springfield Insurance Co., to pay the partners Salomon Sharruf and Elias Eskenazi P40,000 plus 8% interest ISSUE: W/N Sharruf & Eskenazi has juridical personality and insurable interest HELD: YES. Reversd. Insurance companies are absolved. It does not appear that in changing the title of the partnership they had the intention of defrauding the insurance companies fire which broke out in the building at Nos. 299-301 Muelle de la Industria, occupied by Sharruf & Eskenazi but no evidence sufficient to warrant a finding that they are responsible for the fire So great is the difference between the amount of articles insured, which the plaintiffs claim to have been in the building before the fire, and the amount thereof shown by the vestige of the fire to have been therein, that the most liberal human judgment can not attribute such difference to a mere innocent error in estimate or counting but to a deliberate intent to demand of the insurance companies payment of an indemnity for goods not existing at the time of the fire, thereby constituting the so-called "fraudulent claim" which, by express agreement between the insurers and the insured, is a ground for exemption of the insurers from civil liability acted in bad faith in presenting a fraudulent claim, they are not entitled to the indemnity claimed when the partners of a general partnership doing business under the firm name of "Sharruf & Co." obtain insurance policies issued to said firm and the latter is afterwards changed to "Sharruf & Eskenazi", which are the names of the same and only partners of said firm "Sharruf & Co.", continuing the same business, the new firm acquires the rights of the former under the same policies; 16. Island Sales vs United Pioneers General Construction Company et al FACTS: United Pioneers General Construction Company is a general partnership formed by Benjamin Daco, Daniel Guizona,

Inc. United Pioneers defaulted in its payment hence it was sued and the 5 partners were impleaded as co-defendants. Upon motion of Island Sales, Lumauig was removed as a defendant. United Pioneers lost the civil case and the trial court rendered judgment ordering United Pioneers to pay the outstanding balance plus interest and costs. It further decreed that the remaining 4 codefendants shall pay Island Sales in case United Pioneers property will not be enough to satisfy its indebtedness to Island Sales.

ISSUE: What is the extent of the liability of the partners considering that one partner was removed as a co-defendant on motion of Island Sales? HELD: Their liability is pro-rata pursuant to Article 1816 of the Civil Code. But is should be noted that since there were 5 partners when the purchase was made in behalf of the partnership, the liability of each partner should be 1/5 (of the companys obligation) each. The fact that the complaint against Lumauig was dismissed, upon motion of the Island Sales, does not unmake Lumauig as a general partner in the company. In so moving to dismiss the complaint, Island Sales merely condoned Lumauigs individual liability to them. 17. Dela Rosa vs. Ortega Go-Cotay 18. Goguilay and Partnership vs. Sycip et. Al. Reyes J& L: & Facts: Tan Sin and Goguilay into a partnership in business of buying and selling real state properties. Partners stipulated that Tan Sin will be the managing partner and that heirs shall represent the deceased partnership incurred debts and Tan Sin died, he was represents the deceased partner should the 10 years lifetime of the partnership has not yet expired. When the partnership incurred debts and Tan Sin will be managing partnership has not yet expired. When the partnership incurred and Tan Sin died, he has represented by his widow. In order to satisfy the partnerships debts the widow sold the properties to defendant. Goquilay opposed the sail assailing that widow has no authority to do so, without his Kn. Issue:

th

Noel Sim,Augusto Palisoc and Romulo Lumauig. In 1961, United Pioneers purchased by installment a motor vehicle from Island Sales,

Whether or not the consent of the other partner way necessary to perfect the sale of the partnership properties. Riling: First, Goquilay is stopped from asserting that upon the death of Tan Sin, his management of partnership affairs had also been terminated. He was stopped in the same that after the death of Tan Sin, the partnership affairs from 1945 to 1949. It is only when the sale with the defendant that the authority of the widow was questioned. It is a well settled rule that third persons. Are not bound in entering into a contract with any of the two partners, the ascertain whether or not his partner with whom the transaction is made has the consent of the other partner. The public need not make inquiries as to the agreement had between the partners. Its knowledge has enough that it is contracting with the partnership which is represented by one of the managing partners.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- De Castro-Legal EthicsDocument17 pagesDe Castro-Legal EthicsMaricelBaguinonOchate-NaragaPas encore d'évaluation

- Para Sa Short and Sweet Calls: 15 Centavos Per Second To USA, UK, Canada, Australia, China, Hawaii, Hong Kong, MalaysiaDocument1 pagePara Sa Short and Sweet Calls: 15 Centavos Per Second To USA, UK, Canada, Australia, China, Hawaii, Hong Kong, MalaysiaBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- PH Ruling on Forcible Abduction with RapeDocument9 pagesPH Ruling on Forcible Abduction with RapeBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Delisting of CompanyDocument3 pagesDelisting of CompanyBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Maurice Nicoll The Mark PDFDocument4 pagesMaurice Nicoll The Mark PDFErwin KroonPas encore d'évaluation

- AbellaDocument21 pagesAbellaBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

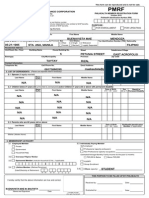

- Philhealth FormDocument2 pagesPhilhealth FormBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Parañaque and Pasig City Regional Trial Courts Contact GuideDocument4 pagesParañaque and Pasig City Regional Trial Courts Contact GuideBuenavista Mae Bautista0% (1)

- E6 ApplicationformDocument2 pagesE6 ApplicationformBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- White Chocolate Cookie Dough FudgeDocument4 pagesWhite Chocolate Cookie Dough FudgeBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Inventory Request of Supplies: Person-In-Charge ForDocument1 pageInventory Request of Supplies: Person-In-Charge ForBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Treasurer's AffidavitDocument1 pageTreasurer's AffidavitMelis BironPas encore d'évaluation

- PDF Expert GuideDocument25 pagesPDF Expert GuideBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- CivDocument2 pagesCivBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Template Judicial AffidavitDocument7 pagesTemplate Judicial AffidavitBuenavista Mae Bautista100% (1)

- Affidavit of OwnershipDocument1 pageAffidavit of OwnershipBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- 2.63 - Bautista, BMMDocument2 pages2.63 - Bautista, BMMBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Crim Part 2Document20 pagesCrim Part 2Buenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Baking LifDocument7 pagesBaking LifBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Ordinance 0524Document3 pagesOrdinance 0524Buenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- PDF Expert GuideDocument25 pagesPDF Expert GuideBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Unlawful Detainer & Forcible Entry Case RulesDocument16 pagesUnlawful Detainer & Forcible Entry Case RulesBuenavista Mae Bautista100% (1)

- Phil PottsDocument1 pagePhil PottsBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- HS Admission Application FormDocument4 pagesHS Admission Application FormBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- CANON 3 Section 5Document14 pagesCANON 3 Section 5Buenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- AOI Template SECDocument15 pagesAOI Template SECEdison Flores0% (1)

- Baking LifDocument7 pagesBaking LifBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- PDF Expert Guide PDFDocument31 pagesPDF Expert Guide PDFBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- October 31, 2012Document1 pageOctober 31, 2012Buenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- Malacanang HistoryDocument4 pagesMalacanang HistoryBuenavista Mae BautistaPas encore d'évaluation

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeD'EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)D'EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Évaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItD'EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeD'EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerD'EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceD'EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingD'EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnD'EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceD'EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaD'EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryD'EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealD'EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureD'EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersD'EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersÉvaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaD'EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyD'EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyÉvaluation : 3.5 sur 5 étoiles3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreD'EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)D'EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Évaluation : 4.5 sur 5 étoiles4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesD'EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesÉvaluation : 4 sur 5 étoiles4/5 (821)

- The Abomination Awakens PFDocument9 pagesThe Abomination Awakens PFNever discoPas encore d'évaluation

- Alexander V MGM OrderDocument31 pagesAlexander V MGM OrderTHROnlinePas encore d'évaluation

- Progressive Development v. QC - 172 SCRA 629 (1989)Document6 pagesProgressive Development v. QC - 172 SCRA 629 (1989)Nikki Estores GonzalesPas encore d'évaluation

- Superior Commercial Enterprises IncDocument6 pagesSuperior Commercial Enterprises IncRalph HonoricoPas encore d'évaluation

- Paper Craft - 280 MoldesDocument424 pagesPaper Craft - 280 MoldesDijeja92% (83)

- Notice of Default - Hillsborough County Court & Tampa Police DepartmentDocument3 pagesNotice of Default - Hillsborough County Court & Tampa Police DepartmentAbasi Talib BeyPas encore d'évaluation

- 76 - 033Document6 pages76 - 033rajaPas encore d'évaluation

- Catindig Vs Vda. de Meneses GR No. 165851 February 2, 2011Document2 pagesCatindig Vs Vda. de Meneses GR No. 165851 February 2, 2011Marilou Olaguir SañoPas encore d'évaluation

- BLR Midterm QuizDocument7 pagesBLR Midterm QuizDjunah ArellanoPas encore d'évaluation

- Ifim Business Law m2Document100 pagesIfim Business Law m2Sachin MittalPas encore d'évaluation

- COMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore Campus: Boys Hostel Admissiom FormDocument2 pagesCOMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore Campus: Boys Hostel Admissiom FormCh ZubairPas encore d'évaluation

- Association of Small Landowners in The Philippines vs. Honorable Secretary of Agrarian ReformDocument1 pageAssociation of Small Landowners in The Philippines vs. Honorable Secretary of Agrarian ReformLuz Celine CabadingPas encore d'évaluation

- RENT AGREEMENT AtrDocument4 pagesRENT AGREEMENT AtrakashsattwikeePas encore d'évaluation

- Debt dispute letter to collections agencyDocument5 pagesDebt dispute letter to collections agencyACPas encore d'évaluation

- Tort Revision Note - Employer Duty of CareDocument7 pagesTort Revision Note - Employer Duty of Carewinnie0v0Pas encore d'évaluation

- Sale of 250 sqm agricultural landDocument2 pagesSale of 250 sqm agricultural landYushene SarguetPas encore d'évaluation

- Tamil Nadu Ordinance On Area Sabha and Ward CommittesDocument10 pagesTamil Nadu Ordinance On Area Sabha and Ward Committesurbangovernance99Pas encore d'évaluation

- Catindig vs. de MenesesDocument2 pagesCatindig vs. de MenesesTeresa Cardinoza100% (2)

- Lee Vs Dir. of Lands (GR 128195)Document7 pagesLee Vs Dir. of Lands (GR 128195)Rosana SilvaPas encore d'évaluation

- Arthur Sanders, Jr. v. State of Georgia, 424 U.S. 931 (1976)Document2 pagesArthur Sanders, Jr. v. State of Georgia, 424 U.S. 931 (1976)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Pointers in Contract of SalesDocument10 pagesPointers in Contract of SalesGabriel EboraPas encore d'évaluation

- Air France v. Saks, 470 U.S. 392 (1985)Document13 pagesAir France v. Saks, 470 U.S. 392 (1985)Scribd Government DocsPas encore d'évaluation

- Beja, Sr. vs. Court of AppealsDocument4 pagesBeja, Sr. vs. Court of AppealsMark SantiagoPas encore d'évaluation

- Allied Bank Vs CIR, GR 175097Document2 pagesAllied Bank Vs CIR, GR 175097katentom-1Pas encore d'évaluation

- Law of Sale of GoodsDocument19 pagesLaw of Sale of GoodsShivam SethPas encore d'évaluation

- REM 1 Rule 1 - 5Document30 pagesREM 1 Rule 1 - 5Ato TejaPas encore d'évaluation

- Mancherster Vs Sun Insurance CaseDocument4 pagesMancherster Vs Sun Insurance CaseJustin Andre SiguanPas encore d'évaluation

- Atci v. Echin G.R. No. 178551Document11 pagesAtci v. Echin G.R. No. 178551albemartPas encore d'évaluation

- Eodb EgsdDocument32 pagesEodb Egsdalexes24Pas encore d'évaluation

- Roque Vs LapuzDocument2 pagesRoque Vs LapuzJames Evan I. ObnamiaPas encore d'évaluation