Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Summary - Eager Seller Stony Buyers

Transféré par

Gaurav KumarCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Summary - Eager Seller Stony Buyers

Transféré par

Gaurav KumarDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Summary Eager seller Stony buyers Studies show New-Product Adoption products fail at the stunning rate of between

40% and 90%, depending on the category, and the odds havent changed much in the past 25 years. In the U.S. packaged goods industry, for instance, companies introduce 30,000 products every year, but 70% to 90% of them dont stay on store shelves for more than 12 months. Most innovative products those that create new product categories or revolutionize old onesare also unsuccessful. According to one study, 47% of first movers have failed, meaning that approximately half the companies that pioneered new product categories later pulled out of those businesses. Example - consider three high-profile innovations whose performances have fallen far short of expectations: Webvan spent more than $1 billion to create an online grocery business, only to declare bankruptcy in July 2001 after failing to attract as many customers as it thought it would. In spite of gaining the support of Apples Steve Jobs, Amazons Jeff Bezos, and many high-profile investors, Segway sold a mere 6,000 scooters in the 18 months after its launch a far cry from the 50,000 to 100,000 units projected. Although TiVos digital video recorder (DVR) has garnered rave reviews since the late 1990s from both industry experts and product adopters, the company had amassed $600 million in operating losses by 2005 because demand trailed expectations

New products often require consumers to change their behavior. As companies know, those behavior changes entail costs. Consumers incur transaction costs, such as the activation fees they have to pay when they switch from one cellular service provider to another. They also bear learning costs, such as when they shift from manual to automatic automobile transmissions. People sustain obsolescence costs, too. For example, when they switch from VCRs to DVD players, their videotape collections become useless. psychological costs: People irrationally overvalue benefits they currently possess relative to those they dont. clash in perspectives: Executives, who irrationally overvalue their innovations, must predict the buying behavior of consumers, who irrationally overvalue existing alternatives. The results are often disastrous: Consumers reject new products that would make them better off, while executives are at a loss to anticipate failure. This double-edged bias is the curse of innovation. concept relative advantage and identified it as the most critical driver of new-product adoption. This argument assumes that companies make unbiased assessments of innovations and of consumers likelihood of adopting them. Although compelling, the theory has one major flaw: It fails to capture the psychological biases that affect decision making.

Gains and losses First, people evaluate the attractiveness of an alternative based not on its objective, or actual, value but on its subjective, or perceived, value. Second, consumers evaluate new products or investments relative to a reference point, usually the products they already own or consume. Third, people view any improvements relative to this reference point as gains and treat all shortcomings as losses. Fourth, and most important, losses have a far greater impact on people than similarly sized gains, a phenomenon that Kahneman and Tversky called loss aversion.

The endowment effect. Loss aversion leads people to value products that they already possess those that are part of their endowment more than those they dont have. According to behavioral economist Richard Thaler, consumers value what they own, but may have to give up, much more than they value what they dont own but could obtain. Thaler called that bias the endowment effect. Status quo bias. Kahneman and Tverskys research also explains why people tend to stick with what they have even if a better alternative exists. In a 1989 paper, economist Jack Knetsch provided a compelling demonstration of what economists William Samuelson and Richard Zeckhauser called the status quo bias. Building a behavioural framework: Innovations and behavior change. Consumers and behavior change. Companies and behavior change.

Balancing Product and Behavior Changes

Accepting Resistance

Be patient - The simplest strategy for dealing with consumer resistance is to brace for slow adoption.

Management consultant Geoffrey Moores recommendations about how to cross the chasm and sell products to the pragmatic consumer applies in this context.To be successful, companies must anticipate a long, drawn-out adoption process and manage it accordingly.

Strive for 10 improvement - Another approach to managing customer resistance is for companies

to make the relative benefits of their innovations so great that they overcome the consumers overweighting of potential losses.

Eliminate the old - When facing unavoidable consumer resistance, a company can eliminate

incumbent products.

Seek out the unendowed - A company can also seek out consumers who are not yet users of

incumbent products

Minimizing Resistance

Make behaviorally compatible products- Companies can reduce or eliminate the behavior change

that innovations require and thereby create smash hits. Toyota embraced this tactic with its hybrid electric vehicles, like the Prius. The Prius provides drivers with both the traditional internal-combustion engine and an innovative, selfcharging electric engine. The result is a driving experience that is virtually identical to that of a gasoline-only car. Consumers obtain a significant increase in gas mileage, yet they retain all the benefits of the entrenched alternative.

Find believers - Another option is for a company to seek out consumers who prize the benefits they

could gain from a new product or only lightly value those they would have to give up. In the case of hydrogen-powered fuel cell vehicles, for instance, businesses must target environmentally conscious consumers. Less obviously, they can also target consumers for whom access to central refueling stations isnt a problem.

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- EcofDocument6 pagesEcofAnish NarulaPas encore d'évaluation

- Goodyear's Aquatred Launch and New Distribution ChannelsDocument20 pagesGoodyear's Aquatred Launch and New Distribution ChannelsRonak GildaPas encore d'évaluation

- B2B - Group 3 - Jackson Case StudyDocument5 pagesB2B - Group 3 - Jackson Case Studyriya agrawallaPas encore d'évaluation

- CumberlandDocument12 pagesCumberlandmadhavjoshi63Pas encore d'évaluation

- Making Stickk Stick: The Business of Behavioral EconomicsDocument6 pagesMaking Stickk Stick: The Business of Behavioral Economicsdeepanshu singhPas encore d'évaluation

- ITC Interrobang Campus Finals - Team Victorious SecretDocument19 pagesITC Interrobang Campus Finals - Team Victorious SecretGourab RayPas encore d'évaluation

- Virgin Mobile - Case StudyDocument13 pagesVirgin Mobile - Case StudyPurnendu Singh0% (1)

- Cumberland Case Study SolutionDocument2 pagesCumberland Case Study SolutionPranay Singh RaghuvanshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 10 Addon: Targeting Impulse Case Analysis Important FactsDocument3 pagesGroup 10 Addon: Targeting Impulse Case Analysis Important FactsAnamika GputaPas encore d'évaluation

- Case AnalysisDocument7 pagesCase AnalysisParth KhadgawatPas encore d'évaluation

- Give IndiaDocument8 pagesGive IndiaKartik GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- 03 Montreaux Chocolate 13Document4 pages03 Montreaux Chocolate 13omkar gharatPas encore d'évaluation

- Kinetic Engineering CompanyDocument13 pagesKinetic Engineering CompanyPRIYA KUMARIPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 6 - IMC Assignment Lipton BriskDocument6 pagesGroup 6 - IMC Assignment Lipton BriskSpandanNandaPas encore d'évaluation

- Sombrero - Proposed Fruit Juice Outlet PDFDocument19 pagesSombrero - Proposed Fruit Juice Outlet PDFAngeli Aurelia100% (1)

- WEC Case AnalysisDocument15 pagesWEC Case AnalysisAkanksha GuptaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reckett Benckiser Case AnalysisDocument4 pagesReckett Benckiser Case AnalysisAman kumar JhaPas encore d'évaluation

- Complete Exhibit 3. Provide The Answers in A Table FormatDocument5 pagesComplete Exhibit 3. Provide The Answers in A Table FormatSajan Jose100% (2)

- Classic Knitwear Case (Section-B Group-1)Document5 pagesClassic Knitwear Case (Section-B Group-1)Swapnil Joardar100% (1)

- Assignment 15021Document118 pagesAssignment 15021Pavi Nambiar0% (2)

- NACCO Case PrepDocument2 pagesNACCO Case Prepmiriel JonPas encore d'évaluation

- Eileen FisherDocument2 pagesEileen FisherAmit Jha50% (2)

- Montreaux Chocolate USA: Are Americans Ready For Healthy Dark Chocolate?Document8 pagesMontreaux Chocolate USA: Are Americans Ready For Healthy Dark Chocolate?DHARAHAS KORAPATIPas encore d'évaluation

- Case-Commerce Bank: Submitted By, Debarghya Das PRN No.18021141033Document5 pagesCase-Commerce Bank: Submitted By, Debarghya Das PRN No.18021141033Rocking Heartbroker DebPas encore d'évaluation

- Proctor & Gamble in India:: Gap in The Product Portfolio?Document6 pagesProctor & Gamble in India:: Gap in The Product Portfolio?Vinay KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- MoS Section A - Group 8 - Case3Document3 pagesMoS Section A - Group 8 - Case3Vatsal MaheshwariPas encore d'évaluation

- Goodyear - Group 3Document4 pagesGoodyear - Group 3Prateek Vijaivargia0% (1)

- How viral videos spread new ideas and influence popularity according to the diffusion of innovations modelDocument3 pagesHow viral videos spread new ideas and influence popularity according to the diffusion of innovations modelDiv KabraPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Analysis: Group 2Document7 pagesCase Analysis: Group 2gaurav sahuPas encore d'évaluation

- Case Synopsis Section-A AquatredDocument5 pagesCase Synopsis Section-A AquatredAggyapal Singh JimmyPas encore d'évaluation

- Spencer Tire PurchaseDocument28 pagesSpencer Tire PurchaseJitendra Choudhary0% (2)

- Case Analysis: Montreaux Chocolate USA: Are Americans Ready For Healthy Dark Chocolate?Document39 pagesCase Analysis: Montreaux Chocolate USA: Are Americans Ready For Healthy Dark Chocolate?Srijan SaxenaPas encore d'évaluation

- GiveIndia's Online Marketing StrategyDocument2 pagesGiveIndia's Online Marketing StrategyAryanshi Dubey0% (2)

- Sparsh Nephrocare - IMC Interim ReportDocument11 pagesSparsh Nephrocare - IMC Interim ReportSamyak RajPas encore d'évaluation

- MDCM Case Write UpDocument16 pagesMDCM Case Write UpKurt MarshallPas encore d'évaluation

- Consumer Perception On Super ShampooDocument16 pagesConsumer Perception On Super ShampooAmit BhalaniPas encore d'évaluation

- Avellin's Marketing Strategy for New Eco7 Motor OilDocument2 pagesAvellin's Marketing Strategy for New Eco7 Motor OilRahul AgarwalPas encore d'évaluation

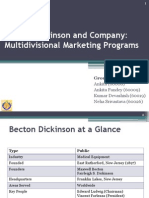

- Becton Dickinson and CompanyDocument19 pagesBecton Dickinson and CompanyAmitSinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Summary and AnswersDocument9 pagesSummary and Answersarpit_nPas encore d'évaluation

- Chai Teab Bags Case - Group 3Document14 pagesChai Teab Bags Case - Group 3Pakshal JainPas encore d'évaluation

- Green Hills Market LoyaltyDocument5 pagesGreen Hills Market LoyaltyLakshmi SrinivasanPas encore d'évaluation

- TWA grp8Document10 pagesTWA grp8Aryan Anand100% (1)

- Curled Metal Inc.-Case Discussion Curled Metal Inc. - Case DiscussionDocument13 pagesCurled Metal Inc.-Case Discussion Curled Metal Inc. - Case DiscussionSiddhant AhujaPas encore d'évaluation

- ChotuKool Case AnalysisDocument4 pagesChotuKool Case AnalysisaishabadarPas encore d'évaluation

- Group 9 - GirishDocument23 pagesGroup 9 - GirishKostub GoyalPas encore d'évaluation

- CASE STUDY ANALYSIS: LONDON OLYMPICS 2012 TICKET PRICINGDocument6 pagesCASE STUDY ANALYSIS: LONDON OLYMPICS 2012 TICKET PRICINGSwati Babbar0% (1)

- METABOLICDocument8 pagesMETABOLICRajat KodaliPas encore d'évaluation

- Department of Management Studies Marketing Management: Case Study ReportDocument16 pagesDepartment of Management Studies Marketing Management: Case Study ReportAakanksha Panwar100% (1)

- TiVo 2002 Consumer Behavior Report Analyzes Subscriber Growth IssuesDocument11 pagesTiVo 2002 Consumer Behavior Report Analyzes Subscriber Growth IssuesVijaya Suryavanshi100% (1)

- AJANTA PACKAGING Sample Situation AnalysisDocument2 pagesAJANTA PACKAGING Sample Situation AnalysisMIT RAVPas encore d'évaluation

- Eco7 AnalysisDocument11 pagesEco7 AnalysisDewang PalavPas encore d'évaluation

- Cabo San Viejo Loyalty Program CaseDocument2 pagesCabo San Viejo Loyalty Program CaseAarjav ThakkarPas encore d'évaluation

- Simulation Report On Ites Metochos Axia: Akshat Goyal 18P185Document4 pagesSimulation Report On Ites Metochos Axia: Akshat Goyal 18P185AkshatPas encore d'évaluation

- Super Shampoo Case Analysis for Rural Indian Mass MarketDocument20 pagesSuper Shampoo Case Analysis for Rural Indian Mass MarketJohn Manavalan0% (1)

- Group 33 CRM Hubble Contact LensesDocument6 pagesGroup 33 CRM Hubble Contact LensesSuman GoswamiPas encore d'évaluation

- The Curse of Innovation A Theory of Why Innovative New Products FailDocument36 pagesThe Curse of Innovation A Theory of Why Innovative New Products FailamaestrovPas encore d'évaluation

- Essay Sellers and BuyersDocument2 pagesEssay Sellers and BuyersJuan Carlos FloresPas encore d'évaluation

- CBM Unit-5Document18 pagesCBM Unit-5dimpureddy888Pas encore d'évaluation

- Ch3 - Reconstruct Market BoundariesDocument42 pagesCh3 - Reconstruct Market Boundariestaghavi1347Pas encore d'évaluation

- CHAPTER 11 Eco MarketingDocument4 pagesCHAPTER 11 Eco MarketingHaMai LePas encore d'évaluation

- Important Telephone Numbers for UP Health DeptDocument2 pagesImportant Telephone Numbers for UP Health DeptGaurav KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Chopra3 PPT ch08Document24 pagesChopra3 PPT ch08Md.Mazed AbdullahPas encore d'évaluation

- The Gist AUG 2013Document69 pagesThe Gist AUG 2013Gaurav KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Soren ChemicalDocument2 pagesSoren ChemicalGaurav Kumar63% (8)

- OM Assignment II Baria Planning Solutions, Inc: Fixing The Sales ProcessDocument5 pagesOM Assignment II Baria Planning Solutions, Inc: Fixing The Sales ProcessSabir Kumar SamadPas encore d'évaluation

- Privatisation in IndiaDocument5 pagesPrivatisation in IndiaGaurav KumarPas encore d'évaluation

- India-S Energy SecurityDocument16 pagesIndia-S Energy SecurityvinoaecPas encore d'évaluation

- Indian Retail SectorDocument60 pagesIndian Retail Sectorwetnwild_nikPas encore d'évaluation

- OM Assignment II Baria Planning Solutions, Inc: Fixing The Sales ProcessDocument5 pagesOM Assignment II Baria Planning Solutions, Inc: Fixing The Sales ProcessSabir Kumar SamadPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Title: Prof. Maninder SinghDocument44 pagesProject Title: Prof. Maninder SinghvijaybhushanmeenaPas encore d'évaluation

- Project Title: Prof. Maninder SinghDocument44 pagesProject Title: Prof. Maninder SinghvijaybhushanmeenaPas encore d'évaluation

- UNDP Procurement Strategy 2015-17Document20 pagesUNDP Procurement Strategy 2015-17UNDPPas encore d'évaluation

- A Research Agenda For Social EntrepreneurshipDocument17 pagesA Research Agenda For Social EntrepreneurshipValéria GonçalvesPas encore d'évaluation

- Continental Valves LimitedDocument19 pagesContinental Valves Limitedbiswasdipankar05Pas encore d'évaluation

- Dhanlaxmi BankDocument95 pagesDhanlaxmi BankNidhi Mehta0% (2)

- We Exceed Expectations: Annual Report 2021Document120 pagesWe Exceed Expectations: Annual Report 2021Jayesh KalePas encore d'évaluation

- The Project Manager of The Future: Developing Digital-Age Project Management Skills To Thrive in Disruptive TimesDocument16 pagesThe Project Manager of The Future: Developing Digital-Age Project Management Skills To Thrive in Disruptive TimesDiego TejadaPas encore d'évaluation

- Managing: Jonathan Liebenau MG 305 LSE, 20 OCT 2020Document36 pagesManaging: Jonathan Liebenau MG 305 LSE, 20 OCT 2020Prakash SinghPas encore d'évaluation

- Management University of Africa: Lecturer'S NameDocument19 pagesManagement University of Africa: Lecturer'S NameMBAMBO JAMESPas encore d'évaluation

- Ines FaguasDocument33 pagesInes FaguasInés FaguásPas encore d'évaluation

- The World Today Is Quite Different Than It Was 20 Years BackDocument5 pagesThe World Today Is Quite Different Than It Was 20 Years BackAnonymous OP6R1ZSPas encore d'évaluation

- GT 0112Document84 pagesGT 0112NuM NaPas encore d'évaluation

- Lanquill StrategyDocument13 pagesLanquill StrategyShubhamJoshiPas encore d'évaluation

- Innovative Tele-Sales Warrior - 2 PDFDocument11 pagesInnovative Tele-Sales Warrior - 2 PDFAlan LeonPas encore d'évaluation

- Walmart Macroenvironment Analysis - EditedDocument11 pagesWalmart Macroenvironment Analysis - EditedErick KinotiPas encore d'évaluation

- Parallel Sessions of 1st ICGBEC2016 - V6Document8 pagesParallel Sessions of 1st ICGBEC2016 - V6Shona TahseenPas encore d'évaluation

- Sean Flynn, "Evaluating Interactive Documentaries: Audience, Impact and Innovation in Public Interest Media"Document168 pagesSean Flynn, "Evaluating Interactive Documentaries: Audience, Impact and Innovation in Public Interest Media"MIT Comparative Media Studies/WritingPas encore d'évaluation

- 1 Entrepreneurial Opportunity CH 1 NotesDocument3 pages1 Entrepreneurial Opportunity CH 1 NotesDev SadanaPas encore d'évaluation

- Infrastructure Management ThesisDocument31 pagesInfrastructure Management Thesisriuslex0% (1)

- World Health Report 2012: No Health Without A ResearchDocument151 pagesWorld Health Report 2012: No Health Without A ResearchInternational Medical Publisher100% (1)

- Critical Success Factors of Sme Internationalization: Khulna University, Bangladesh T.bose.1@research - Gla.ac - UkDocument23 pagesCritical Success Factors of Sme Internationalization: Khulna University, Bangladesh T.bose.1@research - Gla.ac - UksofikhdyPas encore d'évaluation

- The Future of FinTech Paradigm Shift Small Business Finance Report 2015Document36 pagesThe Future of FinTech Paradigm Shift Small Business Finance Report 2015Jibran100% (3)

- India and Uk FinalDocument12 pagesIndia and Uk FinallibinsuguPas encore d'évaluation

- BIM-Optimized Cost Estimation and Scheduling with BIMestiMateDocument11 pagesBIM-Optimized Cost Estimation and Scheduling with BIMestiMateOscarKonzultPas encore d'évaluation

- Molecular GastronomyDocument12 pagesMolecular GastronomyAshneet KaurPas encore d'évaluation

- EY UK Fintech Census 2019Document24 pagesEY UK Fintech Census 2019Dennis TanPas encore d'évaluation

- Budget Rent A Car - StrategyDocument15 pagesBudget Rent A Car - Strategydevam chandra100% (1)

- Organisational Development Strategy - 2011-12-2015-16Document33 pagesOrganisational Development Strategy - 2011-12-2015-16grisPas encore d'évaluation

- Evolution of Operations Management Past, Present and FutureDocument30 pagesEvolution of Operations Management Past, Present and Futurenaveni100% (1)

- Hong Kong, China: Measuring Innovation in Education 2019Document2 pagesHong Kong, China: Measuring Innovation in Education 2019Kapil Rampal100% (1)

- Compensation and BenefitsDocument79 pagesCompensation and Benefitsmad4hr100% (2)