Académique Documents

Professionnel Documents

Culture Documents

Bev

Transféré par

msragabCopyright

Formats disponibles

Partager ce document

Partager ou intégrer le document

Avez-vous trouvé ce document utile ?

Ce contenu est-il inapproprié ?

Signaler ce documentDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

Bev

Transféré par

msragabDroits d'auteur :

Formats disponibles

BEVS CERAMICS AND CRAFTS

In August of 1994 Bev Campbell contemplated purchasing a mould of a maritime fishing village and harbour scene which she believed would appeal to tourists. Bev was the owner / manager of Bevs Ceramics and Crafts located in Lower Sackville, twenty minutes from Halifax , Nova Scotia. She was anxious to expand into new markets, especially in light of the recent decline in sales. A friend, the former manager of a boutique catering to tourists, suggested that Bev expand into the tourism market. She was seriously considering this option but did not feel she had sufficient information on which to base her decision. COMPANY BACKGROUND Company History and Proprietors Background: Since the mid 1980s Bev Campbell has had a passion for ceramics. Her passion began as a hobby and by the latter part of 1991, it had mushroomed into a full time business Bevs Ceramics and Crafts. The transition from hobby to business was prompted by the difficulty Bev had in finding a job after the two video stores she managed for four years were closed. Community organizations approached her to teach ceramics classes and, since there were no firing facilities nearby, she acquired a small kiln. Bev became the full time owner / manager of the business assisted by her two adult daughters, Teresa and Catherine. Bev held a Bachelor of Fine Arts with a major in crafts and a Bachelor of Arts with a major in psychology. She was a skilled craftsperson and took pride in the quality of her work. Bev enjoyed all aspects of the business - the creativity, the teaching and the management. She enjoyed watching the talent and the self- esteem of her students develop. The development of her students was particularly rewarding in cases where students had arthritis or other conditions that made it difficult for them to do other crafts. The business began with one kiln and about 150 moulds. A second kiln and additional moulds were acquired, financed through operations. She estimated that the business owns approximately $20,000 worth of moulds at cost. Bev hoped to expand her business to a point where she could make a comfortable living doing what she loved to do.

This case was prepared by Professor E. Hicks of Mount Saint Vincent University for the Acadia Institute of Case Studies as a basis for classroom discussion, and is not meant to illustrate either effective or ineffective management. Copyright 1995, the Acadia School of Business Administration, Acadia University. Reproduction of this case is allowed without permission for educational purposes, but all such reproduction must acknowledge the copyright. This permission does not include publication.

-1-

Products, Services and Distribution: Bevs Ceramics and Crafts sold supplies and ceramics, at various stages of completion. The business also provided kiln firing services and ceramics classes and workshops. In 1993 33% of the gross revenue was from the sale of supplies; 32% from the sale of unfired, semi-finished products (greenware); 19% from firing services; 7% from the sale of fired, semi-finished (bisque); 6% from the sale of finished ceramic products; and 3% from classes. Although the classes account for a small portion of the gross revenue, Bev was of the opinion that the classes promoted the sale of supplies, semi-finished products and firing services. The company had a wide variety of moulds. Bev purchased a variety of moulds from different suppliers based on what she believed would be popular. The cost of the mould depended on the size and the detail of the mould as well as its popularity. The cost of the mould was also determined by supplier, transportation costs, and duty. In the case of more expensive moulds, Bev generally waited until she had firm orders for at least five units before she purchased the mould. A wide diversity of ceramic products were produced by the company. Products ranged in size from small thimbles to large decorative lawn ornaments. They also varied in terms of complexity. The company produced everything from simple, utilitarian items such as coffee mugs and salt and pepper shakers to very intricate, esoteric items such as villages, angels and wizards. The sale of supplies, semi-finished products and firing services to ceramic hobbyists were predominantly to walk-in traffic. The business was located in the basement of Bevs rented home. Although the house was not located in a high retail traffic area, it was on a busy road within short walking distance of three malls and the main street in Lower Sackville. The premises were predominantly designed to accommodate ceramics classes and production rather than the aesthetic display of ceramic products. In the past, a number of methods for distributing finished products have been employed. Bev attended, on average, three craft shows annually and sold between $200 and $800 worth of finished products at each show. The craft shows also promoted her business by creating customer awareness of her companys products and services. Provided the craft show sales covered the costs associated with the craft show, Bev felt that the business had received the benefit of free advertising. Bev had also placed finished products on consignment with gift and craft stores. Generally, she had been dissatisfied with the loss of control over the display and exposure of her products in the craft stores and the time it took to receive payment from consignees for goods sold. Bev had attempted to interest florist shops in purchasing quality ceramic vases for their floral arrangements but florists were not enthusiastic. The florists believed it would have been difficult to pass the cost of the more expensive vases on to their customers. -2-

Consequently, she had only received a few small orders. Accounting System and Financial Position Bev Ceramics and Crafts was a cash business. All sales were cash and all supplies were purchased for cash. Bev considered it fortunate that the company never had any debt. As she said, I could close up the business at any time and not have to be concerned about creditors. However, cash flow was tight and it was sometimes difficult to meet the rent and utility payments on time. The accounting records were maintained on a computer spreadsheet by month with columns for each category of sales and each type of cost. The records were primarily designed to determine the sales tax liability. One of Bevs daughters, Teresa, was in the process of setting up the company on a point of sales software program. Although formal financial statements were not prepared, an income statement for the year ended December 31, 1993 was prepared for income tax purposes by Teresa (see Appendix A). Financial statements for 1991 and 1992 were not prepared. The following additional information related to the 1993 income statement was available: (a) the cost of goods sold only includes materials used in production; (b) maintenance refers to the regular maintenance required on the kilns; (c) depreciation of the moulds was calculated using the straight line method and an estimated useful life of two years; (d) electricity includes both power to run the kilns ($541.44) and power for heat and lights in the shop ($1,236.51); (e) shop rent amounts to $350 per month; and (f) the income statement does not reflect depreciation of the kilns. The kilns were purchased second hand for $550 and Bev estimated that they would have a ten year useful life and no residual value. During 1993 Bevs Ceramics and Crafts used approximately 93 boxes of clay and the kilns were turned on for a total of 752 hours or 5,414 kilowatt hours. Supplies and greenware sales together accounted for 65% of sales. The breakdown of gross sales for 1993 is shown in Appendix B. CERAMIC CRAFT INDUSTRY The craft industry was highly competitive and seasonal in nature. There was a demand for crafts and ceramics and to capitalize on this demand the number of annual craft shows had increased over the years. The number of craftspersons had also increased substantially over the years, partly due to poor economic times. People who had received pay cuts or who had been laid off had been making and selling crafts to supplement their incomes. During poor economic times the sale of semi-finished products have tended to increase, while during good economic times the sale of finished products had tended to increase. Bev considered her biggest competitor of bisque and finished products to be the flea markets. The items sold at the flea market were often poor quality but consumers did not generally recognize and appreciate quality. There were other businesses similar to her -3-

own but she did not regard them as direct competition because they were not located in the vicinity. As well, there were so many ceramic products that no one business could carry everything. Ceramic based businesses frequently refered customers to one another. Customers were willing to travel to obtain the particular item they wanted but they were not willing to travel for firing. In addition two ceramics companies, one in the nearby community of Dartmouth and one in the Annapolis Valley, produced bisque in quantity for a lower price but these companies only carried a narrow line of products. Ceramics were considered by many artists to be a borderline craft. Some artists argued that there was no originality unless the craftsperson was involved in making her/his own moulds. Ceramics could have been crafted with or without challenge and originality. In Bevs opinion, ceramics could have been compared to an artists canvas. The talent of the ceramics artists would have been evident in how the ceramics were cleaned, painted and finished just as the talent of a painter would have been evident from the painting on the canvas. Unfortunately, as with other craft\art forms, consumers did not always recognize quality. CERAMICS - MANUFACTURING PROCESS The ceramic manufacturing process begins with mixing the liquid clay or slip and pouring it into plaster moulds (day 1). This is left to set until the item can support itself at which time it is removed from the mould. The item is left to dry for two to three days depending on its size. At this stage the product is known as greenware . The greenware is rough and must be cleaned, sanded and washed to remove imperfections, such as seams where the two halves are joined. After cleaning, the greenware may be fired (day 4). The firing takes a full day. After cleaning and firing the product is known as bisque. Various surfacing techniques, such as painting or glazing, may then be applied to the bisque on the next day (day 5). If the bisque has been glazed, then it is fired once more (day 6). The finished product is ready for sale approximately five or six days from the time the liquid clay is poured. This process is outlined in Appendix C. Each kiln can fire many items at once depending on the size of the item. The small kiln is 2.9 cubic feet with a capacity for 27 kg. of product while the large kiln is 5 cubic feet in size with a capacity for 55 kg. The moulds must be left to dry between pours. If a mould is used to pour one day then it should stand for two days to dry. A mould can be used to pour up to three small units or one large unit each pouring day. Gradually, as moulds are used, their fine detail becomes less evident. Bev estimated, on average, a mould was good for approximately 100 pours. When moulds no longer met Bevs specifications for detail, they were sold for an insignificant amount to ceramic hobbyists. Although Bev enjoyed all aspects of producing ceramics, the fine dust from sanding and cleaning greenware bothered her eyes. She tended to leave the fine detailed painting to her daughters because her eyesight was not sharp enough for fine, detailed work.

-4-

PRICING POLICY The pricing of products was very important. The demand for the products depended to a large extent on the price, that was, demand was elastic. Bev tried to set a price that would have sold her products quickly but she also wanted to ensure the price would have recovered her costs and provided a reasonable return to the business. Recently Bev noticed cherubs, in bisque form, being sold at a craft store at a price that would have covered not much more than her cost of materials. She considered offering to supply the craft store with these items at a comparable price but decided it was not worth her while. Bev believed that her pricing policy was appropriate and that she priced her products in accordance with the market. Most supplies, including clay or slip, were grossed up by 80% of cost. Cost included delivery and GST. Ceramics were priced based on the price of the mould which was one of the methods suggested in some ceramics literature. Greenware was priced at 10% of the cost of the mould (including shipping and GST). The 10% was based on recovering the cost of the mould over 10 pours. Pricing of bisque and finished items was based on the greenware price. Bisque that had been cleaned by the customer was priced at 140% of the greenware price whereas shop cleaned bisque was 200% of the greenware price. Finished, unglazed products were priced at 300% while finished, glazed products were priced at 400% of the greenware price. For example, if a mould cost $100 then the product prices at various stages of completion would have been as follows: Greenware ($100 x 10%) $10 Bisque, customer cleaned ($10 x 140%) $14 Bisque, shop cleaned ($10 x 200%) $20 Finished, unglazed ($10 x 300%) $30 Finished, glazed ($10 x 400%) $40 An alternate pricing policy suggested in ceramics literature was based on the cost of the clay or slip used in the production of the item. Under this method greenware was priced at ten times the cost of the clay or slip used to produce the item. The current records only reflected the profitability of the company as a whole. They did not reveal whether or not the current pricing policy had been sufficient to recover all costs and return a reasonable profit to the company on an individual item basis. The current records did not reflect this information because costs were not traced or allocated to specific items. PROJECTED COSTS AND REVENUES ASSOCIATED WITH ENTERING TOURISM MARKET Bev anticipated that the sale of ceramics to tourists would have been in the finished (unglazed) product stage. Since her shop was not located in a tourism area, the -5-

products would have been sold, predominantly wholesale, to retail shops catering to tourists. Retail stores expected to purchase the ceramics at half the retail price. However, Bev believed that the ceramics might have retailed for more than the normal 300% of the greenware selling price - perhaps as much as 550% of the greenware selling price. Thus a finished, unglazed ceramic item produced from a $100 mould would normally have sold for $30, calculated as $100 10 x 300%, might have sold for as much as $55, calculated as $100 10 x 550%, to tourists. To appeal to the tourism market, Bev considered purchasing a mould of a maritime fishing village and harbour. The mould was large and costs $132. It was expected to be used to pour 100 items after which it would have been disposed of for a negligible amount. Bev Ceramics & Crafts was a seasonal business with its busiest times of the year being late summer and fall in preparation for Christmas ceramics. Business picked up to a lesser extent prior to Halloween, Valentines Day and Easter. If Bev were to enter the tourism market the bulk of the production would take place during January, February, and March which were slow months for the business. With one fishing village mould, Bev estimated that she could produce three units per week from January through March. If the product was successful and more orders came in she would continue to produce during April through July as well and purchase additional moulds as needed. A 15.876 kg. box of clay or slip costs $6.67. Bev estimated that each fishing village unit would use 3 kg of clay. Approximately one bottle of acrylic paint was required to paint 1.5 kg. of finished units. Each firing took approximately eighteen hours: six hours while the kiln was turned on, followed by twelve hours while the kiln was turned off. At full production, Bev would have needed to hire a part time person to help with mixing and pouring the liquid clay or slip. It was difficult to mix the clay and serve customers at the same time. In addition the moulds with liquid clay were very heavy to lift. She estimated that at full production she would require one part time person for two hours each morning, five days per week at the minimum wage of $7.17 per hour (including employer contribution to Canada Pension, and Unemployment Insurance). This employee could mix and pour approximately five boxes (15.876 kg. per box) of clay or slip in the two hour period. Approximately one hour of Bevs and / or her daughters time would have been required to clean each unit of greenware and four hours to finish each unit. Although, they would not have been paid salary or wages for their time, Bev believed that she could hire someone to do the cleaning and finishing for the minimum wage. Based on 1993 operations, kiln maintenance costs were approximately $0.30 per hour that the kiln was turned on and it was anticipated that cost of delivering products to retail outlets would average $3 per unit. All other costs were expected to remain constant. Appendix D outlines the costs associated with producing and delivering the fishing village unit. -6-

CONCLUSION Since production for the tourism market must begin in January, Bev needed to decide whether to enter this market or not. Between August and January she would have to produce a prototype of the fishing village scene for showing retail store buyers in order to obtain firm orders for the coming spring. Bev was concerned about the slump in sales year and was anxious to take steps to correct the situation. Although tourism was a major industry in Nova Scotia, she wondered whether she should pursue the tourism market as a means of increasing sales and profits of her business. She was concerned about whether expansion into the tourism market would be worthwhile.

-7-

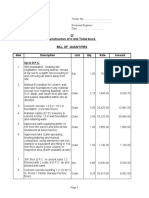

Appendix A Bevs Ceramics and Crafts Income Statement For the Year Ended December 31, 1993 Gross sales Cost of goods sold: Purchases Less: increase in inventory Cost of goods sold Gross profit Expenses: Maintenance expense Meals and entertainment Motor vehicle expenses Computers and equipment Depreciation expense - moulds Electricity Rent Total expenses Net loss $15, 424.42

$7,319.37 2,877.05 ________ 4,442.32 _________ 10,982.10

213.66 65.05 513.52 67.74 4,910.01 1,777.95 4,200.00 ________ 11,747.93 _________ $ 765.83 _________

Appendix B Bevs Ceramics and Crafts Gross Sales by Product and/or Service 1993 Supplies Greenware Firing Bisque Finished products Classes and workshops Total gross sales $5,128.81 4,925.57 2,827.14 1,078.64 946.00 518.26 ________ $15,424.42 ________ -833% 32% 19% 7% 6% 3% _____ 100% _____

Appendix C Bevs Ceramics and Crafts Manufacturing Process

Liquid clay (raw materials) l l Plaster mould (mould clay) l l Greenware semi-finished state (moulded clay) l l Cleaned and kiln fired l l

<------------

Bisque semi-finished product l l Surface techniques l l

<------------

Finished product (unglazed) l l <------------Glazed and kiln fired l l Finished product (glazed)

-9-

Appendix D Bevs Ceramics and Crafts Costs Associated with the Production and Delivery of Fishing Village Unit

Clay or slip Electricity - firing * Maintenance - kiln Part time help ** Paints, glazes, decals Cost of mould Delivery

$6.67 per 15.876 kg. box $0.10 per kilowatt hour $0.30 per hour $7.17 per hour $1.50 per bottle $132.00 per maritime fishing village mould $3.00 per unit

* The large kiln uses 7.2 kilowatts of power for each hour that the kiln is on while the small kiln uses approximately 3.4 kilowatts of power. ** Includes employer contribution to Canada Pension Plan and Unemployment Insurance

-10-

Vous aimerez peut-être aussi

- Value Chain Management Capability A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionD'EverandValue Chain Management Capability A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionPas encore d'évaluation

- Green Acres Farmers MarketDocument9 pagesGreen Acres Farmers MarketyuniartiPas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus For Managerial EconomicsDocument18 pagesSyllabus For Managerial EconomicsCharo GironellaPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2Document8 pagesModule 2ysa tolosaPas encore d'évaluation

- Reaction Paper - Garpaz Enterprises Inc.Document3 pagesReaction Paper - Garpaz Enterprises Inc.Jes CamilanPas encore d'évaluation

- Stake In, or Claim On, Some Aspect of A Company's Products, Operations, MarketsDocument5 pagesStake In, or Claim On, Some Aspect of A Company's Products, Operations, MarketsPaul Mark DizonPas encore d'évaluation

- E1 Enterprise Operations SyllabusDocument3 pagesE1 Enterprise Operations SyllabusKarrthikesu NadarajahPas encore d'évaluation

- 2syllabus - FM 1 - Financial Management 1-BSA2Document9 pages2syllabus - FM 1 - Financial Management 1-BSA2Acesians TagumPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 4 - Organization and Management AspectDocument3 pagesModule 4 - Organization and Management AspectYolly DiazPas encore d'évaluation

- Cash Management ArokianewmanDocument133 pagesCash Management ArokianewmaneswariPas encore d'évaluation

- SUCS - Budget Primer - Budget ExecutionDocument62 pagesSUCS - Budget Primer - Budget ExecutionAiEnma100% (1)

- Business Law Taxation - Course OutlineDocument7 pagesBusiness Law Taxation - Course OutlineMuhammad SalmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Accounting ReviewerDocument9 pagesAccounting ReviewerG Rosal, Denice Angela A.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Syllabus in Business FinancDocument8 pagesSyllabus in Business FinancRoNnie RonNiePas encore d'évaluation

- Topic 20 - Project FeasibilityDocument3 pagesTopic 20 - Project FeasibilityJanus Aries SimbilloPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 52 Adventist HomeDocument1 pageChapter 52 Adventist Homeno namePas encore d'évaluation

- Chapters 8 9Document14 pagesChapters 8 9Mayrah Rose ClaravallPas encore d'évaluation

- Asfaw, Audit II Chapter 5Document3 pagesAsfaw, Audit II Chapter 5alemayehu100% (1)

- AC 42 Accounting For Partnerships and Corporations SyllabusDocument14 pagesAC 42 Accounting For Partnerships and Corporations SyllabusMaybelle EspenidoPas encore d'évaluation

- MKT 173 Export Marketing: Ateneo de Manila UniversityDocument7 pagesMKT 173 Export Marketing: Ateneo de Manila UniversityJonalyn CacanindinPas encore d'évaluation

- Tourism Related EstablishmentsDocument15 pagesTourism Related EstablishmentsAndoy LagmanPas encore d'évaluation

- Type of AccountsDocument4 pagesType of AccountsIgnacio De LunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Distribution Management: Get To Know Each OtherDocument43 pagesDistribution Management: Get To Know Each OtherBuyco, Nicole Kimberly M.Pas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Credit ManagementDocument48 pagesIntroduction To Credit ManagementHakdog KaPas encore d'évaluation

- Good Gorvernanc-WPS OfficeDocument11 pagesGood Gorvernanc-WPS Officeclarisse villegas100% (2)

- FAR 0-ValixDocument5 pagesFAR 0-ValixKetty De GuzmanPas encore d'évaluation

- MGT06 TQM - Syllabus - 2016-2017 (2ND)Document8 pagesMGT06 TQM - Syllabus - 2016-2017 (2ND)Christelle De Los CientosPas encore d'évaluation

- Revised BSA Curriculum Approved by CHED Technical PanelDocument42 pagesRevised BSA Curriculum Approved by CHED Technical PanelLei100% (2)

- 20201st Sem Syllabus Auditing Assurance PrinciplesDocument10 pages20201st Sem Syllabus Auditing Assurance PrinciplesJamie Rose AragonesPas encore d'évaluation

- Opertions Auditing - SyllabusDocument4 pagesOpertions Auditing - SyllabusMARIA THERESA ABRIOPas encore d'évaluation

- Module 2 - Strategy FormulationDocument70 pagesModule 2 - Strategy FormulationRatchana VasudevPas encore d'évaluation

- Responsibility Accounting ModuleDocument12 pagesResponsibility Accounting ModuleDUMLAO, ALPHA CYROSE M.Pas encore d'évaluation

- MANAGERDocument8 pagesMANAGERzealousPas encore d'évaluation

- Organizational-Development SyllabusDocument4 pagesOrganizational-Development Syllabustheaa banezPas encore d'évaluation

- MODULE 6 LESSON 1 - Operating Cycle and Cash Conversion CycleDocument6 pagesMODULE 6 LESSON 1 - Operating Cycle and Cash Conversion CycleJenina Augusta EstanislaoPas encore d'évaluation

- Manaorg NotesDocument5 pagesManaorg NotesLeonardoPas encore d'évaluation

- Seatworks PrelimDocument1 pageSeatworks PrelimRegina CoeliPas encore d'évaluation

- OBE Syllabus Operations Management With TQM San Francisco CollegeDocument4 pagesOBE Syllabus Operations Management With TQM San Francisco CollegeJerome SaavedraPas encore d'évaluation

- Demand Forecasting QuizDocument8 pagesDemand Forecasting QuizJawwad KhanPas encore d'évaluation

- Internal Control - DrillDocument10 pagesInternal Control - DrillTeofel John Alvizo Pantaleon100% (1)

- Unit I Accounting Standards Part 1Document50 pagesUnit I Accounting Standards Part 1Chin FiguraPas encore d'évaluation

- Learning Packet (CAE19) BSA 3Document36 pagesLearning Packet (CAE19) BSA 3Judy Anne RamirezPas encore d'évaluation

- Literature Review: BasedDocument7 pagesLiterature Review: BasedsalmanPas encore d'évaluation

- OM 493: Management of Technology Projects: Spring 2012 Course Syllabus Section 001Document5 pagesOM 493: Management of Technology Projects: Spring 2012 Course Syllabus Section 001Anant Mishra100% (1)

- Case Study in MGT 4Document4 pagesCase Study in MGT 4Kunal Sajnani100% (1)

- 69547314Document3 pages69547314Jasmin GabitaPas encore d'évaluation

- Common Practices in Business OrganizationsDocument6 pagesCommon Practices in Business OrganizationssPas encore d'évaluation

- Operations Management TQMDocument67 pagesOperations Management TQMWingmannuu100% (1)

- Finn 22 - Financial Management Questions For Chapter 2 QuestionsDocument4 pagesFinn 22 - Financial Management Questions For Chapter 2 QuestionsJoongPas encore d'évaluation

- Management Science SyllabusDocument10 pagesManagement Science SyllabusPaul Mark Dizon100% (1)

- Basic Business Finance 07Document8 pagesBasic Business Finance 07knockdwnPas encore d'évaluation

- Carlo Recio Business PolicyDocument6 pagesCarlo Recio Business PolicyRia Dumapias0% (1)

- ACP 314 Auditing and Assurance Principle Rev. 0 1st Sem SY 2020-2021Document12 pagesACP 314 Auditing and Assurance Principle Rev. 0 1st Sem SY 2020-2021Jerah TorrejosPas encore d'évaluation

- Quantitative Techniques ReviewerDocument3 pagesQuantitative Techniques ReviewerAstronomy SpacefieldPas encore d'évaluation

- Case StudyDocument53 pagesCase StudyJosephC.CachoPas encore d'évaluation

- Elec 4 Managing A Service Enterprise SyllabusDocument13 pagesElec 4 Managing A Service Enterprise SyllabusIvanGil GodelosonPas encore d'évaluation

- Innovation Mgt-ObeDocument8 pagesInnovation Mgt-ObePlongzki TecsonPas encore d'évaluation

- MANAGEMENT SCIENCE SyllabusDocument2 pagesMANAGEMENT SCIENCE SyllabusKasaragadda Mahanthi50% (2)

- 3.FINA211 Financial ManagementDocument5 pages3.FINA211 Financial ManagementIqtidar Khan0% (1)

- Case Study of ABC Company BankruptcyDocument12 pagesCase Study of ABC Company BankruptcyBuffy Marie AguilarPas encore d'évaluation

- Its - Sl500 Error LogDocument43 pagesIts - Sl500 Error LogmsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- NP CompletenessDocument30 pagesNP CompletenesssharmilaPas encore d'évaluation

- Som TSPDocument9 pagesSom TSPsingharunkantPas encore d'évaluation

- Airplane Perceptron ClassifierDocument8 pagesAirplane Perceptron ClassifiermsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- README Install ItDocument1 pageREADME Install ItmsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- Process Owner - Role DescriptionDocument2 pagesProcess Owner - Role DescriptionmsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- PPP DVol4 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol4Document73 pagesPPP DVol4 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol4msragabPas encore d'évaluation

- PPP DVol6 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol6Document73 pagesPPP DVol6 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol6msragabPas encore d'évaluation

- Why IQ Tests Don't Test IntelligenceDocument1 pageWhy IQ Tests Don't Test IntelligencemsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- PPP DVol6 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol6Document73 pagesPPP DVol6 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol6msragabPas encore d'évaluation

- PPP DVol7 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol7Document73 pagesPPP DVol7 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol7msragabPas encore d'évaluation

- ASG How To Populate Your CMDB enDocument8 pagesASG How To Populate Your CMDB enmsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- PPP DVOL3 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol3Document77 pagesPPP DVOL3 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol3msragabPas encore d'évaluation

- PPP DVol5 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol5Document76 pagesPPP DVol5 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol5msragabPas encore d'évaluation

- Teradyne - The Jaguar Project CaseDocument11 pagesTeradyne - The Jaguar Project Casemsragab100% (3)

- PPP DVOL1 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol1Document78 pagesPPP DVOL1 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol1msragabPas encore d'évaluation

- PPP DVOL2 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol2Document73 pagesPPP DVOL2 TXT Presentation Diagrams Vol2msragabPas encore d'évaluation

- Building Effective R& D Capabilities AbroadDocument11 pagesBuilding Effective R& D Capabilities AbroadmsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- Oracle SQL ReferenceDocument5 pagesOracle SQL ReferencemsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- A&d High Tech MisDocument10 pagesA&d High Tech MisTwisha PriyaPas encore d'évaluation

- Planning and Building Data CenterDocument16 pagesPlanning and Building Data Centermsragab100% (1)

- Theoretical Computer Science Cheat SheetDocument10 pagesTheoretical Computer Science Cheat SheetKoushik MandalPas encore d'évaluation

- Corporate Governance in AsiaDocument33 pagesCorporate Governance in AsiamsragabPas encore d'évaluation

- Perpetual InjunctionsDocument28 pagesPerpetual InjunctionsShubh MahalwarPas encore d'évaluation

- Supply Chain Risk Management: Resilience and Business ContinuityDocument27 pagesSupply Chain Risk Management: Resilience and Business ContinuityHope VillonPas encore d'évaluation

- Jainithesh - Docx CorrectedDocument54 pagesJainithesh - Docx CorrectedBala MuruganPas encore d'évaluation

- Type BOQ For Construction of 4 Units Toilet Drawing No.04Document6 pagesType BOQ For Construction of 4 Units Toilet Drawing No.04Yashika Bhathiya JayasinghePas encore d'évaluation

- AN610 - Using 24lc21Document9 pagesAN610 - Using 24lc21aurelioewane2022Pas encore d'évaluation

- Attachment BinaryDocument5 pagesAttachment BinaryMonali PawarPas encore d'évaluation

- SCHEDULE OF FEES - FinalDocument1 pageSCHEDULE OF FEES - FinalAbhishek SunaPas encore d'évaluation

- Self-Instructional Manual (SIM) For Self-Directed Learning (SDL)Document28 pagesSelf-Instructional Manual (SIM) For Self-Directed Learning (SDL)Monique Dianne Dela VegaPas encore d'évaluation

- TNCT Q2 Module3cDocument15 pagesTNCT Q2 Module3cashurishuri411100% (1)

- Revenue Management Session 1: Introduction To Pricing OptimizationDocument55 pagesRevenue Management Session 1: Introduction To Pricing OptimizationDuc NguyenPas encore d'évaluation

- Adjectives With Cork English TeacherDocument19 pagesAdjectives With Cork English TeacherAlisa PichkoPas encore d'évaluation

- The Fundamentals of Investing PPT 2.4.4.G1Document36 pagesThe Fundamentals of Investing PPT 2.4.4.G1Lùh HùñçhòPas encore d'évaluation

- Actus Reus and Mens Rea New MergedDocument4 pagesActus Reus and Mens Rea New MergedHoorPas encore d'évaluation

- Introduction To Radar Warning ReceiverDocument23 pagesIntroduction To Radar Warning ReceiverPobitra Chele100% (1)

- Incoterms 2010 PresentationDocument47 pagesIncoterms 2010 PresentationBiswajit DuttaPas encore d'évaluation

- Chapter 11 Walter Nicholson Microcenomic TheoryDocument15 pagesChapter 11 Walter Nicholson Microcenomic TheoryUmair QaziPas encore d'évaluation

- CEC Proposed Additional Canopy at Guard House (RFA-2021!09!134) (Signed 23sep21)Document3 pagesCEC Proposed Additional Canopy at Guard House (RFA-2021!09!134) (Signed 23sep21)MichaelPas encore d'évaluation

- Study of Means End Value Chain ModelDocument19 pagesStudy of Means End Value Chain ModelPiyush Padgil100% (1)

- Questionnaire: ON Measures For Employee Welfare in HCL InfosystemsDocument3 pagesQuestionnaire: ON Measures For Employee Welfare in HCL Infosystemsseelam manoj sai kumarPas encore d'évaluation

- Industrial Management: Teaching Scheme: Examination SchemeDocument2 pagesIndustrial Management: Teaching Scheme: Examination SchemeJeet AmarsedaPas encore d'évaluation

- Karmex 80df Diuron MsdsDocument9 pagesKarmex 80df Diuron MsdsSouth Santee Aquaculture100% (1)

- Seminar Report of Automatic Street Light: Presented byDocument14 pagesSeminar Report of Automatic Street Light: Presented byTeri Maa Ki100% (2)

- Dreamfoil Creations & Nemeth DesignsDocument22 pagesDreamfoil Creations & Nemeth DesignsManoel ValentimPas encore d'évaluation

- D6a - D8a PDFDocument168 pagesD6a - D8a PDFduongpn63% (8)

- WPGPipingIndex Form 167 PDFDocument201 pagesWPGPipingIndex Form 167 PDFRaj AryanPas encore d'évaluation

- MSDS Bisoprolol Fumarate Tablets (Greenstone LLC) (EN)Document10 pagesMSDS Bisoprolol Fumarate Tablets (Greenstone LLC) (EN)ANNaPas encore d'évaluation

- Enumerator ResumeDocument1 pageEnumerator Resumesaid mohamudPas encore d'évaluation

- Management Interface For SFP+: Published SFF-8472 Rev 12.4Document43 pagesManagement Interface For SFP+: Published SFF-8472 Rev 12.4Антон ЛузгинPas encore d'évaluation

- Best Practices in Developing High PotentialsDocument9 pagesBest Practices in Developing High PotentialsSuresh ShetyePas encore d'évaluation

- Chap 06 Ans Part 2Document18 pagesChap 06 Ans Part 2Janelle Joyce MuhiPas encore d'évaluation